Text

orchids to dusk

orchids to dusk is a networked (read: multiplayer of a sort) game about wandering on a planet you know nothing about except for the fact that it’s where you are going to die. Your life support system has only a few minutes left, and the only thing to do is spend them traversing the expanse in front of you. I can’t speak much more to it—it’s a quite short game and I don’t want to give it away. If anything about it sounds interesting to you, I advise you check it out.

Specifications

Windows, Mac, Linux

Free (Pay-what-you-want)

~15 minutes

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

People Make Games - The Games Industry Must Not Stay Silent on Palestine

What's happening in Palestine is wrong. Why won't the video games industry say so?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

FAREWELL. - A Send-Off to Blaseball

I’ve got no way to put this that it’ll make sense to someone who wasn’t there. But I’ll try my best, because at this point, recollections are what’s left. The stories told – about something really, really excellent. I said it in my original coverage, but stories are Blaseball. The names and the stats and data are just the materials the fans steals to collage into a narrative of strife and struggle and the whims of fate and community, and it was like nothing else I’ve seen before. And I doubt I’ll easily see it again.

It makes sense. Blaseball in its entire run has never been sustainable in a healthy way. Despite being about as lightweight as you could make a kind of game, it just wasn’t enough for the fast pace. Things like the sun being swallowed by a black hole or the Grand Unslam are wonderful legend pieces, but they’re also proof of the game’s frailty, and the fact that they were embraced by the fandom is partly a stroke of luck. It’s pretty clear that Blaseball can easily run you dry—I myself was rather checked out during the Expansion Era, which I now regret despite circumstances at the time—I don’t blame the Game Band for deciding continuing the game wasn’t worth it. Maybe if the game had been drafted with sustainability from the start, requiring a subscription like an MMO and on a TV show schedule… but it was made as an off-hand project born of frustration at impotence in times of crisis for the sake of profit, a gift of the internet. The way it took off and grew probably wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t you could just sign up for.

Of course, “took off” might be a bit of hyperbole. It exceeded the Game Band’s expectations after they passed the game around to some friends, sure. But the fact is that despite the overwhelming love from the fans, Blaseball is really quite terribly small and niche in the grand scheme of the internet. It mostly existed on Twitter, a site whose future existence is a great deal more precarious than it was around a year ago. It’s very liable to become a piece of passing trivia, or obscure nostalgia, supposing no Youtuber video essayist makes a rundown that goes 7-figures viral. Obviously, as a man writing for a ‘zine mostly read by his patient friends, I’ve not nearly that influential, but I want to say: Blaseball will not be forgotten, not by me. I love(d) it and it opened my eyes to a wondrous form of narrative and I’ll be thinking about it for the rest of my life.

It was a game of rotten systems, about how disparate people across groups can work as a greater community in order to rebel against those systems, and yes, through rebellion be punished—sometimes dearly for it—but never negating the existence of the rebellion in the first place. It was a lovely loom for weaving sports narrative and the fandom (a good chunk of whom are not sports fans) provided thread with passionate fervor. It was a wonderful testament to collective play and the act of giving a shit.

I’d advise any Blaseball fan to save and archive (preferably physically somewhere) any and all Blaseball media they’ve got on their socials or elsewhere. Even aside from the now seemingly imminent Twitterpocalypse, the Blaseball wiki exists primarily as a way to dispense the events of Blaseball in a clean, matter-of-fact way. It won’t express the reaction tweets, the fan theories, the narrative as it was on the ground. (And for that matter, the wiki itself still has gaps with what is essentially a skeleton crew of editors…) Blaseball was ephemeral in its life and it’s up to fans to stop it from fading.

I am, we all are love Blaseball.

[feedback]

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

my mind looks a lot like a_: a Video Game Playlist

Whether in an abandoned mall or an opulent estate, this playlist is all about embarking on a surreal architectural journey of the psyche. Investigate and explore these vaporwave-influended spaces, witness two speculations on technology of the future, and interrogate your digital reality. It’s Holovista’s mega-mansion house tour internship and the liminal awakening personality profile of Self-Checkout: Unlimited – step on inside.

Holovista

Previously covered, Holovista follows Carmen Razo on her newly acquired and direly needed job working for the innovative high class architectural firm Mesmer & Braid. The first task given to her, however, is a strange one – a field assignment to inhabit the firm’s mysterious new project, the autohaus, and to document her experiences by relaying them to her not-Instagram following. In game, this is achieved by taking photos of a number of requested items in a 360˚ scene, and then match appropriate photos to a caption in order to post them, chatting with your friends over DM (and whatever intern is running the Mesmer & Braid account) along the way. The latter gets only more important, as the autohaus’s design, and Carmen’s own mental state, gets more questionable as her residence goes on.

Fine attention to detail in order to spark immersion is the real crux of Holovista – the rendered scenes that you experience strike a delicate balance between striking realistic fidelity and the dreamlike opulence of the game’s low Sci-Fi future. The environments (at least, the non-creepy ones) are something you’d want to just exist in, partially because they feel so believable and possible. The Social Media interface has comments on every post, and profiles for every commenter, and most important of all, top notch Internet writing. Everybody talks like actual internet users, and several conversations between Carmen and her friends that could have come out of me and my friends. Even the basic gameplay loop puts you directly in Carmen’s shoes – you turn around (or swipe on your screen) to take photos of stuff and then post them just as she does.

This immersion is all put to good use in the story itself then, which reflects that immersion back (though I’ll not elaborate, to avoid spoilers), culminating in a game that’s not really like anything else I’ve ever played.

Specifications

iPhone

$4.99

~2 hrs

Self-Checkout: Unlimited

Self-Checkout: Unlimited, on the other hand, hits upon the environment of slightly oldish an abandoned mall. Starting out with a horror-esque tone as the player character finds themselves in a barely lit hall on a bench, forced to navigate a store housing a terribly unnerving teddy bear before the mall opens up, you are then invited via disembodied intercom to explore various sections and stores of the mall, all with… unusual set-ups focused on psychology. Between children’s rides based off of a fictitious children’s show structured around personality profiles and a clothing store rack with jackets labelled with things like ‘parents’, ‘significant other’, and ‘friends’ on a scale from most to least important, the mall is less a real space to engage in commerce and more a loci for an examination of the self. The surreality is only increased in scenes when the mall fades away in favor of environments with strong vaporwave aesthetics often reflecting other elements of commerce all whilst the interrogation of the self continues on, like a Psych 101 professor giving a lecture over a lo-fi, echoic beat.

Compared to the DM conversations between friends in Holovista, the only form of communication is always faceless – either via seemingly pre-recorded intercom announcements, or by a narrator seemingly talking both to the player character and the player themselves. As the mall is explored further, the unique specifics of the self-examination build towards the context of the mall’s liminality – which I’ll hold back in face of spoilers. The details towards this context are thought-through, perhaps to the point of maybe giving the game away, but in the end it’s a cohesive build that helps take the weight of the philosophizing off a bit.

Specifications

Windows, Mac, Linux

$7.99

~1.5 hrs

Sum Specifications

iOS & Windows/Mac/Linux

$12.98

~3.5 hrs

#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#Video Games#Indie#Holovista#Self-Checkout: Unlimited#Under 5 dollars#Under 10 dollars#Under 20 dollars#Under 5 hours#iOS#Mac#Windows#Linux

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

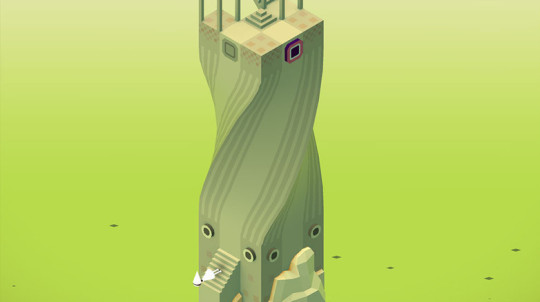

Now Look Here: A Video Game Playlist

Just like the last issue, this is another Video Game playlist – another multiple course recommendation of some games that complement each other mechanically, aesthetically, generically, and/or thematically, and thus would be good to play together.

The Playlist

Comprised of the high profile mobile game classic Monument Valley series and the lesser-known Vignettes, Now Look Here is a playlist all about the wonder of perception. Explore the Escher-based but otherwise concrete and beautiful world of architecture in Monument Valley I and II, and dive into the free-flowing associations of a dream world through transforming objects in Vignettes.

Monument Valley I & II

Previously featured on TBTG in a proto-issue, the Monument Valley series (if you haven’t heard of it already) is about a journey through the titular Monument Valley – a collection of impossible architecture in the vein of M.C. Escher that you manipulate in order to build a path from place to place. The first game follows a disgraced princess trying to make amends over ruins, and the second game is about a daughter’s coming of age. Both have relatively simple puzzling – there’s no state you can get in where you’d have to restart a puzzle, and for almost all the puzzles the way to proceed is quickly discovered – but that’s alright. There’s only so complex you can get with a short game that’s fucking around with something so fundamental as perspective, and the games are built more on the beauty of discovery in the world.

And the world is very much worth discovering. Despite the surreal premise, there’s a specific slice of imaginative realism going on with Monument Valley. Each monument is a work of art that firmly follows a logic based in reality – the mechanical forces powering them are always highlighted through the animation and the controls. The result is that though the world of Monument Valley is definitely not ours, you have a feeling that it couldn’t be too far off, if only.

Specifications

iOS, Android, Windows

$6.99 USD – $9.97 USD (iPhone, Android), $13.58 USD (Panoramic Collection)

~4 hours

Vignettes

In comparison, Vignettes (previously showcased in the first installment of Rapid-fire Recs) goes beyond surreal into a mostly-abstracted dreamlike web of associations in a neon funhouse limited color palette. You’re given an object, and by twirling it around and changing the perspective so the colors often add up in a flat image, it shifts and changes into a different object, usually related to the theme of the first object – though there are other themes that you stumble into by interacting with objects in different ways, accompanied by a change in palette.

Along the way as you double over associations and worm your way around the various objects (like the circular logic of a dream) in order to complete each theme for the main goal of the game, you’ll also stumble upon various components for the ‘secrets’ in the game. Each secret has a hint in the form of a picture, most of which are require at least two different objects. So when you see one part (like a fan), you take note, and then when you stumble upon the second, you’ve got to then backtrack through the objects to bring it back to the first. The various webs of connections throughout get worn in your mind, to the point where you no longer need to open up the map of transformations and instead just jump from transition to transition. The game has the feeling of “what in the goddamn?” that comes with the wonderful, weirdest dreams.

Specifications

iOS, Mac, Windows

$2.99 USD (iPhone), $7.99 USD (Mac, PC)

~3 hours

Sum Specifications

iOS, Windows, (Mac), (Android)

$9.98 – $17.96 USD

~7 hours

#Gaming#Indie#Video Games#Monument Valley#Monument Valley 2#Vignettes#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#Under 5 dollars#Under 10 dollars#Under 20 dollars#Under 5 Hours#Under 10 Hours#Mac#Windows#iOs

0 notes

Photo

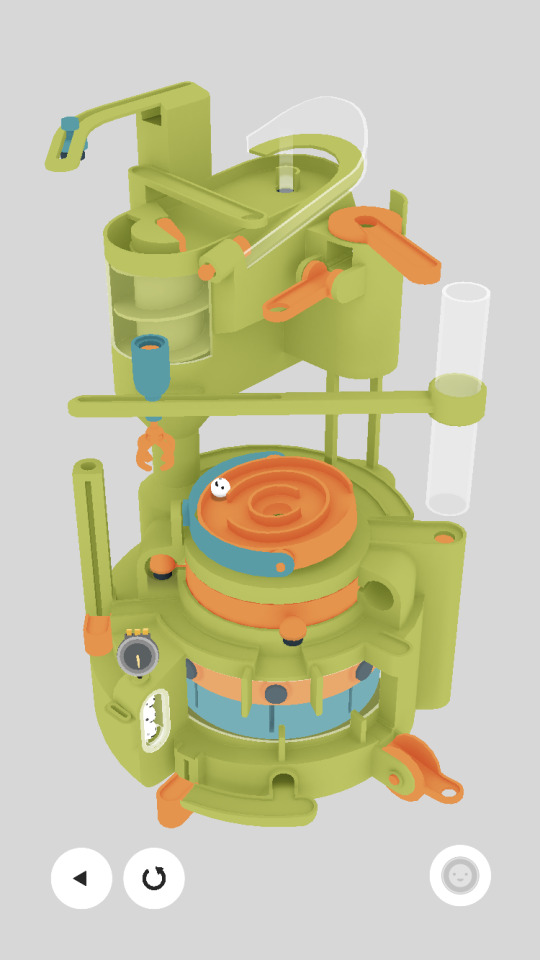

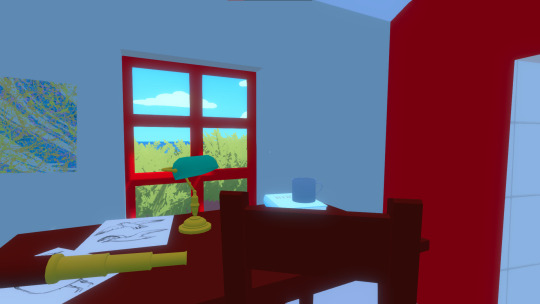

Contraption: a Video Game Playlist

Video Game Playlists are a new style of game recommendation I’m experimenting with – in a similar yet more purposeful fashion to my double feature of NUTS and Alba: a Wildlife Adventure, a playlist will feature recommendations of some games I think complement each other well played consecutively and/or concurrently based on intersections of aesthetic, mechanics, genre, subject matter, and theme. Each playlist will start with a rundown of the games as a set, and then get into each’s individual quirks. With that out of the way, here’s the very first playlist, featuring two games in an oddly specific genre I wish there were more examples of.

The Playlist

Tactile and fiddly, these two games are based around the joy of having a some sort of contraption to mess about with in your hands. Featuring strong sound design that makes interaction pop, vibrant, playful aesthetics, and gameplay that centers discovery, the two games take the idea of a puzzle box and run with it in their own unique directions. GNOG has a fantastical and sometimes silly spin with themed lightly-narrative dioramas, while Automatoys works like a 12 set of interactive steel ball labyrinths that wouldn’t be too out of place in the real world.

GNOG

First off, GNOG is an adventure game (fight me over that assessment!) centered around exploring what are essentially exceptionally fanciful lunchbox dioramas in order to forward their narratives. Oh, also, each diorama is a head, and when you complete what you need to do, they sing. Surreal. They all have various themes – one is based around finding treasure deep in the sea using a submarine, another is themed around a candy shop. The aesthetic is vibrant, though often employing neon hues in order to underpin the weird dimensions each box exists in. In that way, it’s more like what toys looked like in one’s imagination as a child.

Like any good game based around recreating the tactility of physical objects, the sound design is intimate and bountiful – outside of the interactive mechanisms, a good lot of other things you can mouse over to make pleasant sounds, like shaking a rain stick. Admittedly, this can make figuring out which parts are actually important for progressing – GNOG, like many games, can sometimes fall into the difficulties of any game based around nonverbal communication. But it’s mostly sublimated by the simple joy of poking and prodding until you figure out what comes next.

Specifications

Mac, Windows

$9.99 USD

~2 hours

Automatoys

Though also puzzlebox-like and accompanied by a colorful aesthetic, Automatoys takes a kinetic spin, in the style of those spherical metal ball mazes you might have seen in a toy store somewhere. You’re presented with a contraption of mechanisms and automated parts, a happy little ball, and a single task: get it to the goal. Your method of doing this is via tapping (and sometimes touching-and-holding) the screen, which affects every mechanism in the level. Pegs jump, mazes tilt, hammers cock, the relative elevation of a segmented zig-zag path switches – simple. In terms of design, brilliantly so, in terms of gameplay, not a chance after the first few levels have eased you into the gist. For one, since there’s no instruction whatsoever as to how any of the mechanisms work, and you’ve got your eyes on the ball, you’ll usually find out what one does just as you’re approaching it – though you can always approximate a guess – many of the mechanism designs are things in real life, like mazes, or are iterated further in later levels, so you’re rarely completely in the dark. One can, of course, experiment with all the mechanisms before inserting the coin to drop the ball, but aside from ruining the delight in high-pressure discovery, it’s only half the picture without something moving through the level, and as things progress there are a great more things to memorize.

If you cock it up, your ball might be gently rolled back to an earlier part of the level, or it might fall off of the level entirely, obliging you to start from the beginning – though, no worries, your number of tries is infinite. But failure is never punishing or frustrating, partly because when you fail you can try again immediately, and mostly because it never stops being absolutely hilarious how much you can screw up in a game where the only mode of interaction is ‘tap the screen’. It keeps up the playful atmosphere well. And you will cock it up, because though the game has a cute, friendly aesthetic, and is marked as casual, that doesn’t mean it’s not challenging. In level 5, in the middle of fare following the lead of the four levels before is a section where you have to shoot the ball into a hole in plastic tube right when the bottom part of a spinning corkscrew passes by, and it is not easy. There’s a sharp upward incline to the shooting ramp, so you have to release the shot in advance, and the only real clue as to when the corkscrew path is coming around is seeing it around the bend, and by then it’s too late, so the way you time it is by feeling, by instinct, when enough time has passed. Having 100% completed Automatoys, I still fail this shot multiple times when replaying. Playing the first time, however, this is a message from the game: haha, okay, time to stop fucking around.

It’s not a difficulty spike, but after this point, you do have to be a lot more active when playing the game – there are easier ways to fail if you grow complacent, mechanisms and automation become more fine-grained, more intertwined. Often, in addition to having to mentally re-assign what tapping the screen does from section-to-section, what was needed in the preceding the section (tapping the screen, not tapping the screen) is what will fuck you up in the section you’re rolling into. As you get further and further into the game, going through a level becomes more and more of a mental-finger fumble, even when you’ve replayed a level several times.

Because, oh yeah, this game is so very replayable. It’s got a star system: one star for completing a level, two stars for completing it under a brisk timeframe, three stars for completing it under one even more stringent than that. Keeping with the tactile stylings, the timer is built onto the automatoy, too, and it’ll click once you’ve run out of time for a three or two star rating. But that’s only a fraction of the picture. Because while I did put in the work to get a three star rating for every level (except for #7, which, I realize I must have, but I only remembering failing to get above two stars many, many times), I have completed every level at least four or five times minimum simply for the fun of completing them. Replaying a level you know how to run (especially once you’ve gotten good enough to get three stars) feels like an interactive version of one of those ‘so satisfying’ videos that go viral. There were a great many times I procrastinated on writing this issue specifically to go play the game, or where my writing was cut short for the same.

This satisfaction is definitely helped by the game’s sound design, obviously. The rest of the game’s aesthetic, too. The matte-textured, vaguely* Monument Valley-inspired aesthetic in video games is getting pretty oversaturated in a certain stripe of indie game, but here it’s perfect, calling to mind a specific style of colorful plastic. And those colors, aside from (generally) being very full and eye-pleasing, serve a function, too. The main color is the static body of the level, and the two accent colors delineate the controllable mechanisms and the cycling automated parts.

*I say vaguely because the twice-mentioned comparison feels pretty spurious outside of Monument Valley being a famous indie game to compare to for the sake of prestige and/or because nobody’s played anything else that could be relevant.

(Also, it shouldn’t require spotlighting, but it’s one of the only mobile games I’ve seen that does in-app purchases ethically. It can be downloaded for free, which gives you the first three levels to play, and then you pay $2.99 to unlock the full game. How shockingly straightforward and non-insidious is that.)

It’s easy to say with most of the year behind me that Automatoys is was one of the best games I played this year, if not the best, but it is so good, I would’ve had the confidence to say that in January. It’s a game that won me over by being something both incredibly up my alley, and completely out of my way.

Specifications

iOS, Android

Free - $2.99 USD

~1.5 hours

Sum Specifications

Mac/Windows & iOS/Android

$9.99 USD - $12.98 USD

~3.5 hrs

#Gaming#Indie#Video Games#GNOG#Automatoys#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#Free#Under 5 dollars#Under 10 dollars#Under 20 dollars#Under 5 hours#Mac#Windows#iOS

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Rapid-fire Recs

Hey! Haven’t done one of these in a while. This time around, I thought I’d cover tabletop RPGs, a category of game which I’ve always wanted to cover, but the fact of my relative inexperience with them (and much less one single title) compared to video games has always held me back from doing a full issue spotlight. So, without further ado: five TTRPGs that also don’t require a GM!

Moss Creeps, Stone Crumbles

Moss Creeps, Stone Crumbles is a very rules-light and casual friendly TTRPG about documenting a clearing over the course of a century in five year increments. One player first draws a simple image, and then the next player writes a short caption for it. The player who wrote the caption then draws an image from the clearing five years later, and the next player writes a caption for them, looping back to the first player once everyone’s had a go, until 20 of these writing/drawing pairs have been made.

The collaborate storytelling process is a quietly companionable one, as the focus on a location allows your story to escape the traditional framing around Ego and instead explore a biological network of sorts. As drawings don’t need to be of the clearing as a whole, players can and will flit between small elements, with various landmarks or animals or flowers making appearances and reappearances over the course of decades.

And, at the end, you have a physical record of your little clearing that you can keep – the game suggests dividing up a single piece of paper into 20 sections, but my artist’s nature insists it be played on 10 double-sided sheets so it’s easier to turn into a book.

2-20 players, GMless

$1.00 USD

~1.5-2 hours

The Ground Itself

If you want a game set in a single location over a certain advancing timeframe that doesn’t dictate a specific setting, then The Ground Itself does that. Here the world is brainstormed by the players, and then dice roll determines the timeframe – whether the landscape inches forward by a scale of days or millennia. This second bit means that a setting such as a high school could be rendered very different after a single round of the game. The players then draw cards from the deck and answer card specific prompts, after which the time advance is triggered.

Compared to Moss Creeps, Stone Crumbles, The Ground Itself is not focused on images (being a text-oriented game) and snapshot moments, but more concrete systems of culture, society, and history – the world I created was not a collage of scenes but instead a realized world whose various incarnations in time I could use as a setting for a story, or even another TTRPG. So if you want to follow the concrete history of a place, give it a shot.

2-5 players, GMless

$5.00 USD

~3 hours

I Groom Turtles and My Partner Degausses Birds. Our Budget is 1.5 Million.

While Moss Creeps and Ground generally treat their loci with some level of solemn respect, I Groom Turtles absolutely does not. The basic pitch of it is that it’s a parody of Househunters and similar shows – asking the two players playing as the couple to come up with the ‘whitest name they can think of’ for their partner, and for them to come up with what style of house they want independent of each other. There’s also the deathless spectres. Because one thing the realtor has failed to note about the property they’re selling to the other players is that it’s haunted. And as they take the couple through the house, and the couple argue about what renovations they want to make to the rooms, the deathless spectres will have the renovations of their own.

I Groom Turtles’ humor emerges in the melodrama of house selection as mediated by reality TV, as the players stand true to the naked absurdity of their desires for the house in verbal combat negotiation for the final renovation plans. In the end, after the laughter had died down, my friends and I had a floorplan that was an utterly ridiculous hodgepodge of desired features and the frustrating compromises taken to get them, for everyone human and not.

4+ players, GMless

Free

~1 hour

/dia

However, if you’re less interested in places so much as people, or you don’t have anyone around to play TTRPGs with you, or you want a game that goes quick, /dia is a solo TTRPG about writing the singular moment of a character facing imminent death in segmented increments. I hesitate to say much more, as the unfolding format of the rulebook does a lot for the tone and pace of the game, and aside from that a lot of its draw is in its short length. What I can say is that the subject matter is well-suited to the micro size, and for its duration, I was caught up in the world of my character. If you’re still unsure about the idea of a solo TTRPG and ‘journaling games’, this is a complete experience without a large time investment.

1 player

$3.00 USD

30 minutes

Six Figures Under

But if you want a solo TTRPG game that’s longer and wherein the presence of death isn’t a climactic single moment but instead part of the job, Six Figures Under is a game of vignettes about being a freelance necromancer. In it, you write about facets of the job such as fulfilling a client’s request or carefully writing an Ad on Craigslist that can bypass its word-based content filters. That second vignette is also exemplary of the game’s epistolary focus. In all but one of the vignettes, the writing you’re doing isn’t of a framed narrative, but of in-universe documents – the one about fulfilling a client’s request is specifically a journal entry. If you like the freelance work take on a usually mystical job, or an epistolary-focused TTRPG, check it out.

1 player

$1.00 USD

~1-2 hours

#Gaming#Indie#Tabletop RPGs#Moss Creeps Stone Crumbles#The Ground Itself#I Groom Turtles and My Partner Degausses Birds. Our Budget is 1.5 Million.#dia#Six Figures Under#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#Free#under 5 dollars#under 10 dollars#Under 5 Hours#under an hour

1 note

·

View note

Photo

And Other Stories

Presented on a false cinderblock monitor in the midst of an evolving dreamscape that calls to mind the color aesthetics of really compressed GIF files, And Other Stories is an autobiographical exploration of memory quadfold using the Bitsy engine. The experience of playing it is one of scattered attention, as you’re greeted with four Bitsy games running side-by-side (each screen blending into one-another Exquisite Corpse style), and you control the player character for all simultaneously. Each area is littered with interactive objects that fill you in on the memory itself or are part of contextual narration for the scene being set – and you will accidentally bump into these triggers easily.

Pulling your focus in any one story will almost inevitably involve a mental process of “okay, the next narration bit is over there – oh, fuck, someone’s talking to me to me on the left (who are they?), and in walking I’ve accidentally skipped halfway through the narration down there.” It’s disorienting, though perhaps fitting given the recurring theme of drunken festivity for all of the vignettes. Your attention will flit between these linked memories as you piece together the shape of them, if not the exact details.

The dreamscape isn’t just there as a pretty frame to the game, either – the various objects you interact with mutate your surroundings – bottles appear in the blue sea, flowers grow on the monitor’s lower rim, a hearth gradually burns. As you progress, your mindscape will transform, becoming cluttered with the various mementos from each meta-game, though likely not as cluttered as they could be, seeing as you’re also quite likely to stumble into the trigger that forwards the ‘plot’ with no going back.

In the end, this all meant I had to replay the game four times focusing on a different vignette each time to get the full story, which arguably takes away from the intended simultaneity, but I doubt most people would be able to juggle them perfectly, and the writing and subject matter itself is strongly connected enough without immediate juxtaposition. If you’re looking for a little slice of life (albeit one that goes somewhat heavy), or you want to explore experimental storytelling, give it a shot.

Specifications

Windows, Browser

Free

~1.5 hours

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Why Is The Stanley Parable Ultra Deluxe

An Interrogation, An Existential Crisis, A Mental Breakdown

It makes no damn sense! Compels me, though.

- Knives Out (2019), dir. Rian Johnson

I’ve something to get off my chest. And, you know, it’s really hard to open up about this, but I trust you, and I want you to know about it. But… why is the Stanley Parable Ultra Deluxe? Don’t get me wrong, I was pleasantly surprised by the news that the game was coming out in 2018 – I loved the original game in all its absurdity. But at the same time… who was jonesing so much for a remake? The Stanley Parable itself was a perfectly complete product (minus the black box that blocked the art ending) that interrogated the systems of video games, and how the industry dealt with these systems. So why a remastered remake, something usually reserved for big budget games, done to refresh a franchise’s audience, or make reliable bank, or pander to nostalgia, or usually, all three?

...Come to think of it, the games industry has just gotten worse since 2013, hasn’t it. Choice is still always a relevant topic when it comes to talking about games, but is adding more of that enough to explain this indulgence? The game has been pushed back multiple times – presumably out of dedication. And that title – Ultra Deluxe, in illusory gold. Hyperbole to the strongest degree. Remake. Remaster. Repackage. Resell. Reboot?

(More more more more more.) I can’t deny I’d like to see more of Stanley Parable’s absurd, cutting reflection of games and their systems – because, fuck, man, there’s no Game About Games like it. It’s been nearly a decade since the ‘official’ version of the game. Twelveish years since the Half Life 2 mod. So is the increasingly hellish state of the games industry the subject of this jump back into the fray? For it’s not just a remaster, it’s got new content – new content bigger than the original game, the site boasts!

A reddit thread, shortly before the release date of 4/27 was announced theorized that continuous pushbacks were indicative of indefinite rugpull, that there was no game to come. If not for my skepticism about Wreden and Crows Crows Crows putting time and money and goodwill into this venture, I might’ve believed it. The Stanley Parable is so twisty, and absurd, and postmodern that the idea can approach the realm of plausible.

And I guess that’s what has got me in such a twist over this – because I’ve seen the game deliver a wonderfully absurd text that seemed in defiance of the typical, questioning of the systems gamers often took for granted, an absolutely riotous trust fall and now this startlingly, almost parodic decision has me looking around the room to try and spot the foam noses and horns hidden under the business suits. Because there’s got to be something dying to be said that bitched this game. I just hope (and trust) it stays smart and avoids the remake trend of saying nothing novel.

#Video Games#Indie#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#The Stanley Parable#The Stanley Parable Ultra Deluxe#Writin' on Tiny Games

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

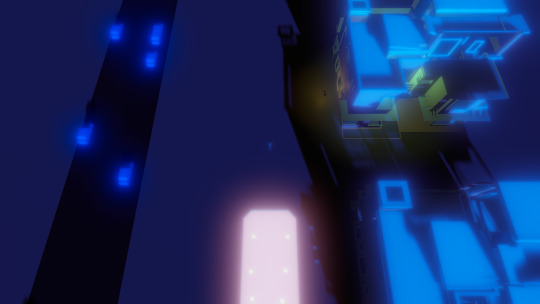

Glitchhikers: The Beta Logs

Around late Fall in 2021, I volunteered to beta-test the Glitchhikers remake, Glitchhikers: the Spaces in Between. I should note that this wasn’t a job, I didn’t get paid, and all I was asked to do was give general feedback on the game after playing it through. Really, it’s a kind of beta-test that functioned more as a mechanism for generating hype than actual beta-testing for a paycheck, which, I admit I have some quibbles with, but hey, I signed up to do it anyway.

This fact of beta-testing means I can’t recommend the game in a normal issue, but it did give me a fair amount of thoughts about the game, so I wrote ‘em down, locked ‘em away, and am now releasing them to the wild now that the game is on the market. I should stress that once again that this is not a recommendation or a review (as if I did those, hah), and it is only my thoughts on what the game looked like still in beta. On with the show, and spoilers abound.

I’m talking to a dragon, or least what used to be a dragon. It used to be one of a legion, proud and powerful, a species with technological might in living flesh, and now, having escaped the end slated for the rest of its kind by packaging itself into data and connecting to the human internet it is utterly alone. As it tells me of the things it has lost through in having to downgrade to our much more primitive technology, it notes that one side effect is distortions, its voice stutters through that last word – and an overhead voice chimes in, telling us what the next stop is. Because the dragon and I, we are two passengers on a communal train, headed somewhere in the night.

I covered the original Glitchhikers (now termed Glitchhikers: First Drive) in my 2020 Hallowe’en Rapid-fire Recs issue, but for the uninitiated, it is a short, experimental game about the of experience driving down a near-empty highway at 12AM and talking about life, the universe, and everything with the various hitchhikers you pick up under the surreal weight of the night. Glitchhikers: the Spaces In Between expands upon that experience, both in adding more fidelity and detail to that specific night driving experience, and by having 3 other journeys that try to bring about that state of mind – The Railway, The Path, and The Terminal.

For the most part, they succeed quite handily. I likely have the least to say about The Highway, having played the original game several times over. What I can say is that they’ve put effort into overhauling the experience on multiple fronts (I replayed the original game after I finished beta-testing). The landscapes you drive by are given much more variance in terms of the natural facets you see, and there are visible changes in the elevation that you’re driving at, too. It’s also just a huge quality bump from the original, I was just shocked at how rough and low-poly First Drive was upon replaying it. Replaying First Drive also showed that the visuals weren’t the only things retooled. The first hitchhiker you meet in Spaces is the same as the one in First Drive, and you do have a slightly different conversation with her, though the essential bits from the original, such as her childhood make-believe with the stars, are still there. (Another detail I like is how the occasional other vehicles will wink in and out of existence on the road as you blink your tired eyes.) You’re still given the choice to exit into the city or keep on driving at the end, and after you complete your first journey an infinite drive mode is unlocked, which is all I ever needed, thank you.

Along with The Highway, The Railway is the only other journey available to you from the start, and it was the one I was the most excited for, because I am huge fan of trains as a transitive space to journey in. So much that a few years ago I briefly drafted up a Tabletop RPG about riding a train, viewing the sights, and having conversations with your fellow passengers. I still think that a Tabletop RPG is a great medium for such a communal activity, but until I pick up the idea again, The Railway serves as an excellent way to satisfy my cravings. Compared to the fleeting interactions that you have with the hitchhikers, with The Railway everyone is on the same train, so you can have progressing conversations with the other passengers as you take in the various sights.

In a manner that aligns with how the player is stationary inside their vehicle on The Highway, freeform movement with the WASD keys does not exist on The Railway, nor any area in the game, aside from The Terminal, which we’ll get to. Instead, there are various hotspots that the player can click on to move to in each room, and progress towards the front of the train. This movement system surprised me at first, since it’s rather unconventional, and I doubt the designers couldn’t just program in traditional WASD movement. This hotspot method is one that de-emphasizes the player’s movement around the train, and instead puts focus on the movement of the train along its tracks.

As with The Highway there’s a sort of role-playing choice, too. As you walk forward in the train cars, there’s an option to get off at whatever stop the train is at instead of continuing on your journey. Perhaps you found a place you wanted to lie low in for a while, or maybe it was your destination all along. There’s enough detail about the stops to make it a meaningful decision, as the overhead announcer (The Railway’s equivalent of The Highway’s late-night radio program) gives a description of wherever you’re headed. At one point when I was on The Railway, the overhead announced that we were approaching a town – I can’t remember the name – that was left in ruins after the practices of a powerful few drove it into the ground, and stated, simply, “We won’t be stopping there.”

The Railway is also where I once again met the Star Woman from The Highway, who appeared as the first hitchhiker in every other journey since, as a way of establishing a baseline of social interaction for your journeys – and to make it clear that you’re able to meet the same hitchhiker across journeys, if it doesn’t happen naturally. The Railway also plays with surreality as a backbone of its structure. Given how you talk with the same people multiple times, instead of forcing you to meander back and forth in the train cars to have your subsequent conversations with a passenger, in The Railway you’re always moving forward, to the front of the train, where the other passengers lie for their next conversation after you finish the preceding one. It makes movement more fluid, and it also adds a sense of forward permanent progress that mirrors your familiarity with the other passengers. Also before you move onto the next group of train cars, you enter one that’s an endless dreamscape completely separate from the movement of the train and the outside world, which works as an introspective pause between conversational rounds, and is just breathtaking and a lovely surprise the first time it happens. Alas, there is not a matching Infinite Ride mode for The Railway. A man can dream.

After completing the The Railway, I moved onto The Path, because that was the order in which they were listed to me, and I am conformist dweeb. Unlike the vehicular basis for The Highway and The Railway, The Path is a walk through a park at night, accompanied by one’s iPod playlist, which is another wonderful fantasy game space, because if I ever tried to take a walk in a park at night with my earbuds in, I fear I’d find myself in a schlocky horror movie. The playlist is alternates between soundtrack songs a mini-podcast that talks about the wonders of life, and aside from occasionally coming across other hikers scattered across the area, you’re left to your thoughts and your playlists as you wander amongst its various sights and structures.

Though perhaps wander isn’t quite the right word, as though The Path forgoes The Railway’s hotspot movement system, it isn’t quite free-roaming, either. Instead, the player can only move forward or backward along the literal walking path as if tethered to an invisible rail. This emphasizes that it is, in fact, a path – your journey is not one of uncharted exploration, it’s walking a route along a local park with some nice sights. There is also an auto-walk key if you get tired of holding down W, which I used liberally.

Even though you’re on a rail, being in a park means that you do have means of deciding where to go along its many paths, and the designers found a way to deal with the directional ambiguity in their unique movement system, too. Whenever approaching a fork, a trail of light will appear and go down whatever path you’re set to go down, giving you time to course-correct. (Aesthetically, it’s fitting that said trail looks like the imprints of headlights in long exposure photographs). Aside from that, there’s not much I can say aside for the fact that the various park decorations are wonderfully varied with a lovely use of space and height, along with some more surreal pocket dimensions. The park is also a location anchored relative to the rest of the journeys, as at a high point on the edge of the park one can look out to see The Highway and the city that lies at the end of it.

Finally, there’s The Terminal, the final journey and a bit of a black sheep, as for it, Glitchhikers finally gives into movement convention and allows for free exploration with the WASD keys inside of a (near) empty airport where all the flights have been delayed. Which – okay, alright, if you are also a conformist dweeb, then the order of the journeys has a progression of more and more player direction, which is nice, but the use of traditional movement tech when everything else has been almost stubbornly experimental, whether through necessity or design, suddenly recasts a sense of doubt about the movement tech of the preceding journeys. If they could’ve done WASD all along, why didn’t they? Which is not to say there isn’t a point to using variant movement tech (I think my previous commentary shows that there is), but that the switch back to the Same Old is somewhat jarring. (Of course, this is where the fact that this is a beta log comes in – maybe the final game will go WASD. I doubt it, but I could be wrong.)

Regardless, going off of the freeform movement in The Terminal – it’s a bit rough in a way that the other, more limited movement schemes aren’t. This isn’t a deal breaker, it’s not worse than, say, a good itch.io Jam game, only that it makes it harder to really immerse one’s self in the game space to be able to embrace the nighttime mood that is its lifeblood. This immersion hindering movement is compounded by the presence of these… grey spheres with varying rings of colour around them (I should note that a rainbow trail of your movement follows you in The Terminal, although my description makes it sound much more gaudier than it its). These spheres, compared to the casual surreality of the past journeys, are overtly… game like. They look like power-ups, and they functionally act like them, too – upon passing through one, you speed up and occasionally are catapulted into the air in a display of physics I don’t really understand, and then all of the other little spheres gets an extra ring of colour.

The Terminal’s wide expanse is about the time you spend in stasis, when you’re left waiting with nowhere to go. With The Railway and The Highway, you had a destination, and with The Path, you were wandering around the park because you liked what it had to offer, it was journey as destination in the simplest form, but with The Terminal the very first thing you hear is a news broadcast (The Terminal’s equivalent of radio program, overhead announcer, or podcast) that all flights have been delayed, indefinitely. You are then left to wander around the premises, killing time. And, admittedly, here the low-poly style of Glitchhikers flounders a bit – it’s always the weakest when trying to express manmade structures – The Terminal is a building of dull blues save the occasional news broadcast, and the architecture is rough in a way that looks unfinished and amateur instead of charming. I can see why the designers might add in the spheres as a way of adding variety to compensate for the much less compelling setting, but I have enough belief in their clarity of vision from the rest of the game that I feel like there surely could’ve been another way to go about it.

All of these factors aside, I want to stress that I do see the point in The Terminal’s divergence from the rest of the game. Aside from the fact that experimentation is good and what birthed First Drive, The Terminal is still about a slightly surreal in-between experience, just a much less aesthetic and more lonesome one. And that change from traveling with a purpose, from talking to many other traveler (in The Terminal there’s just one), does take chops. It’s just that it seems to capture the experience in a less compelling many than any of the other journeys – though perhaps my perspective is a bit biased, as earlier in the year I played the itch.io game Interminal, which tried to express that same experience to greater success. This is not a dig at Glitchhikers, which has an overarching purpose to its terminal beyond just replicating experience, and Interminal has a different aesthetic style and time of day that plays better to the location, but the comparison was not a flattering one.

As mentioned before, The Terminal has only one traveler, once again Starkid Lady, who appears at the bar after you tramp around from news broadcast to news broadcast. This makes your conversation with her denser, even employing a conversational loop wherein your dialogue choices do not move onto a new set of options unless you specifically choose it so. This allows for a more one-on-one conversation that you get anywhere else, which is a nice bookend of the solitude wandering that you engage in before it.

In addition to all of these places, there’s also the first one you see: The Stop. It functions as a physical journey select and what-hitchhikers-have-I-met menu in the form of a rest stop. At The Rest Stop, you can see the various cars that represent The Highway, Infinite Drive, and the Classic Mode unlocked after playing through each journey once which is a strict faithful remake of First Drive. Looking around, you’ll also see the train car that takes you to The Railway, the lamp-lit, thrush-surrounded, trail leading to The Path, and the crossing sign that takes to The Terminal. On the other side is The Stop itself, where you can see which hitchhikers you’ve met and talk to the Clerk to get information about the game. It’s a lovely way of immersing the player into the game’s world.

Also, because The Stop has the most prominent use of the Glitchhikers logo, I’m going to talk about how good it is. The logo is taken from isolating the back-to-back capital Hs in the title, with a heart in between the two of them, literally marking the space in between the two parts of that compound word. But in The Stop, the logo is one of lit signs they have, and as lit signs are wont to do, parts of it are blown. Specifically, the upper stems of each H on the inner sign, transforming them into two chairs facing each other, which is just perfect.

Of course, the locations are only part of Glitchhikers, the other component being the hikers themselves. I only played each journey once in order to not spoil the final game with beta-redundancy, so I only met 10 hitchhikers (aside from Star Lady I had another repeat), but among them I had a wide variety of conversations, from a grieving woman to scientist in awe of the universe to a nihilistic alien child. And these conversations do display a shift in focus from First Drive – the specificity to issues of the real world. Whereas the conversational topics of First Drive trended broadly philosophical, like the scope of the universe, or personal to character’s lives and childhoods, The Spaces In Between drills specifically to the systems of the world: one hitchhiker who debates the ethics and ramifications of technological progress cites how A.I. can replicate racial profiling bias, and another directly calls out Capitalism for stealing away her time to exist as a person and more than a cog in a machine.

This is a bit jarring coming so directly from a video game, but at the same time, it’s necessary change. First Drive was released in 2014, but in 2021 the concept of having deep philosophical and existential conversations about the world is impossible without looking at it in the eye and naming what we see. However, at times, it felt uncomfortable to discussing these topics in the game space, even when I was selecting dialogue options I legitimately agreed with. This might be an unintentional symptom of being on social media, but admittedly, sometimes the frequent references to leftist issues felt like the game was trying to flash its political-philosophical credentials. As it is, politics, and anything dealing with the seamy, seamy issues of the world is something unbelievably complex and nuanced, which is something that games have often struggled with for as long as they have existed – and unlike just wondering about the nature of our existence in the impossibly grand scale universe, it’s much more hefty and loaded, because it deals so much more with the injustice in the world and people fighting to be recognized as human. But occasional awkwardness aside, I stand by the notion that this was the right choice – much better to awkwardly grasp at the truth than try and create an ‘apolitical’ game that ignores something integral to its concept and themes for the sake of keeping the boat steady.

Or, perhaps, maybe the occasional bristling against the anti-capitalistic themes was the mild hypocrisy? I did volunteer to perform free labor on a whim. I’m not accusing the team because I knew it was going to be unpaid, and again, the only thing ‘required’ was a general feedback form instead of the active bug-seeking work the actual beta testers I hope they have are doing. It is, as I said in the intro, more of a hype campaign. But at the same time, it’s not something I can ignore when examining the game’s leftist and anticapitalistic themes.

Aside from the specificity of subject matter (part of which also comes from having a wider swathe of hikers in general), another thing about the hitchikers is that they essentially don’t have a fourth wall. On two different occasions I’ve chosen a dialogue option with my head in the game space, only to be pinned under a metatextually aware response I didn’t see coming. The first time was on The Path, talking to the mourning woman who I had met earlier on The Railway. She asked me what I was planning to do after this, and I figured she’d meant walking in the park. I don’t remember what I answered, except it was casual, and to that she questioned my ability to throw off the weight of the night so easily, saying, “Do these journeys not linger?”

The other time was elsewhere in park, where I was talking to a group of floating crystals about the impact of human on the environment, and they asked “Are we life?” I answered yes, figuring that by we they were referring to themselves as some sort of hive mind, and referencing their digital-looking nature. They challenged me on that, stripping back the curtain and calling every hiker a set of planned responses to designated stimuli. In both moments, I answered an extradiegetic question thinking it was a intradiegetic one – but strangely, I don’t feel tricked. The ambiguity of language is always in play when you’re talking to real people, and for some reason, exposing the game as a constructed reality only emphasizes it as a sort of pocket dimension one can journey to, from time to time.

As far as my beta-testing playthrough went, Glitchhikers: the Spaces In Between was a wonderful experience that did a solid job of expanding on the core experience of the original game. It wasn’t perfect, no, there were stumbles, but even where there were cracks you could see legitimate intent in saying something outside of the aesthetic experience even when that aesthetic experience was pretty damn good, and I think that’s worth a lot. It is very much the remakequel I was hoping for.

#Video Games#Indie#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#Glitchhikers#Glitchhikers: the Spaces in Between#Essay#Writin' on Tiny Games

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bleeding Your Apple Arcade Subscription* Dry

I will always prefer to own games. That will never change. However… I have a shameful confession. I paid for a year of Apple Arcade. Alas. And as it turns out, there are several really good games on it, including ones that aren’t available elsewhere, on Mac or in general. So if you’re looking for the best picks of Apple Arcade, whether it’s to get the most out of your subscription or free trial, here is the TBTG Guide to Bleeding Apple Arcade Dry.

Note: All of these games are available to play on phone and computer, but unless otherwise noted, I played all of them exclusively on laptop, as it’s pretty clear that most of them were made for computer first.

Apple Arcade Exclusives

First up are the games that are available exclusively on Apple Arcade – if either catch your eye, you’ll want to play them first.

Winding Worlds

Winding Worlds is a narrative puzzle game made by ko_op serving up what they do best, which is making games that are digital sensory toys in disguise. Their first game, GNOG, was much more obvious, being a pack of themed puzzle toys, while Winding Worlds is a game about dragging vertically and horizontally to manipulate rotating mini-worlds and the things found inside, all to the audio of some really satisfying sound design. The mechanics are very simple and perfect for phone or tablet (though I played on laptop), and the game is structured semi-episodically, with each level tasking protagonist Willow in exploring an odd fantastical little universe, finding out what’s bothering the denizens, and helping them in their woes. It’s a well-crafted experience that you can just sit yourself into.

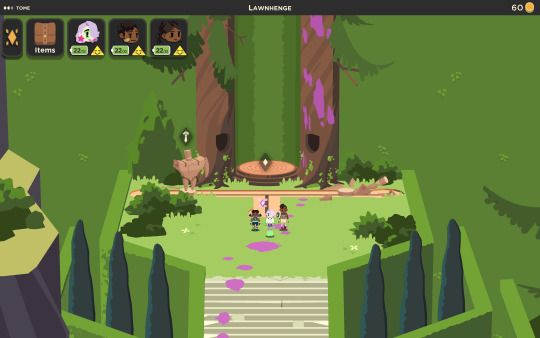

Guildlings

Guildings is a pretty chill character and relationship-driven JRPG in a semi-fantastical world where fantasy hero teams a glory day relic of history, and also their operations were all connected through a smartphone app. The lore and world of this game is a lovely kitchen sink of different influences and I had so much fun getting to explore it with the various characters. The combat is very relaxed, and based around making it to the end of a certain amount of rounds without a total party kill, though there are some side quest challenges. The characters’ actions and abilities are notably dependent on their moods, with some changing the user’s mood, and others requiring a certain mood. This once again puts focus on the social aspects, as the easiest and most natural to change your partymates’ moods (along with the only way to grant them XP for level-up) is in what you choose for your various dialogue options throughout the game. This all made Guildlings one of the nicest RPGs to actually immerse myself in, and actually play the role of my character in a long time.

“Well, Actually” Exclusives

[Pushes up the nose bridge of my glasses] TECHnicalLY, these aren’t exclusive to Apple Arcade, because you can buy them elsewhere, it’s just that the only versions on sale are for Windows. So unless you have access to a Windows OS aside from the Mac device you’re using Apple Arcade with… I’d play these next.

Sayonara Wild Hearts

I already covered Sayonara Wild Hearts in my most recent Rapid-fire Recs installment, but since the game’s relatively high profile and first spot in the list meant that my coverage was a bit light, let me elaborate. The game is akin to an interactive, narrative pop album, taking inspiration from infinite runners and rhythm games as you race along the dreamy, urban fantasyland of the heart. Each level is a short burst of pulse-drumming visuals and pace that draws you straight into the action, and the game goes like a firework: a magnificent burst of sound and light. Fitting, too, then, that it’s barely more than an hour played back-to-back without any slip-ups – though if you’re keen to master songs as is common to rhythm games, that combined with various secrets and achievements are good for replay value.

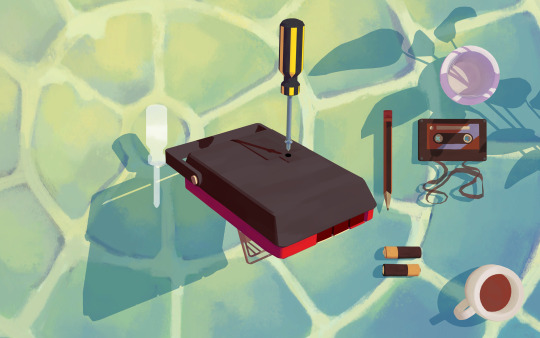

Assemble With Care

Whereas ustwo’s previous games Monument Valley I & II had a fantastical, almost alien geometry aesthetic and the puzzly, tactile joy of manipulated larger-than-life pieces of art and architecture, Assemble With Care goes closer to home, with a warm digital painting aesthetic for the story of a traveling analog repairwoman and the stories of the people who hire her. The game itself is dedicated the act of manually taking apart these storied possessions, repairing and replacing their broken components, and then reassembling them. There’s care taken not automate actions that would otherwise be automated – you have to scroll to screw or unscrew things, tug the end of a cord away from its fastener to wrench it free, and squeeze glue onto components yourself. The experience is only heightened by details such as careful pains to make the 3D models match the painterly aesthetic, with each object actually having two slightly different models that the game alternates between, creating a static-like snap found in two frame painted animations.

Alba: a Wildlife Adventure

I recently covered this game in a full issue, so I’ll keep things short. Alba is a well-tuned photography game taking place on an idyllic island threatened by a hotel development replacing its run-down nature reserve. Existing on the island, and cataloguing its animal inhabitants, along with doing simple tasks that come about in trying to combat ecological damage and repair the reserve is a welcoming and relaxing experience.

The Rest

With those out of the way, here are the rest of the games, which while lesser in priority, are no lesser in quality.

Tangle Tower

I played Tangle Tower in a single sitting, only stopping to take breaks for food or the bathroom. Luckily for me, it’s only 6 hours. An installment in the Detective Grimoire point-and-click adventure game series, though perfectly accommodating to a newcomer like me, it follows Grimoire and his assistant Sally as they puzzle out the murder of a minor member of the sprawling multigenerational Pointer-Fellow family, Flora. You explore the wondrously fantastical world the family lives in, all the while picking up clues and interviewing the various family members, and suss out secrets by pointing out details in the objects you’ve found and making logical connections through a roulette of sentence fragments to truly get to the truth like Sherlock Holmes, instead of the game feeding you answers like you’re Watson. Also, the character design and animation is all so lively and communicative, and the banter between Grimoire, Sally, and the others is fantastic.

NUTS

Like Alba, NUTS was covered recently in a full issue, so a quick rehash of my praises: the game is about tracking the trails of squirrels in Melmoth forest as a part of a study to blockade an amusement park project, using a handful of cameras that feed back to a TV in the caravan you’re stationed at. The experience is mechanically grabbing, the narrative blends themes with the gameplay into an affecting ending, all while backed by a solitary, contemplative environment in dreamy, fog-draped tritone. Squirrel recon has never been this fun.

Mutazione

Mutazione, the best I can describe, is a narrative pilgrimage into the meaning of chosen family, community, and love, through the shoes of Kai, who goes to the eponymously named location to assist her dying grandfather. The game itself is mostly kinetic, with the mechanics mostly centered around peaceful gardening and dialogue options that flesh out character and relationships, both thrusting the player into the world of Mutazione and the various people who live there. And what a world it is: the construction paper cut-out aesthetic is absolutely gorgeous, and bigods I wish it were real – beauty and danger alike.

Post-Publication Addition: Though the author forgot to mention the Animal Crossing-esque camping and befriending sim Cozy Grove, he wholeheartily recommends it. It is available on Apple Arcade, and on Windows via Steam.

#Gaming#Indie#Video Games#Apple Arcade#Winding Worlds#Guildlings#Sayonara Wild Hearts#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#Assemble With Care#Alba: a Wildlife Adventure#Tangle Tower#NUTS#Mutazione#Mac#Windows#under 20 dollars#under 10 hours#Under 5 hours#under an hour#iOS

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Well, Nuts.

This is the second part of a two parter covering the games Alba: A Wildlife Adventure and NUTS. The first part is a typical recommendation of both games, while this is a brief closer look at NUTS. I originally made it out to be grander than that, but admittedly life’s been utterly kicking my ass, and once I already committed I realized that my original idea was not as illustrious as it seemed, but I wanted to get this and my thoughts out anyway. I hope you can glean something from it nonetheless.

There will be spoilers.

I. The world of Nuts is striking – drenched in soft, gradual fog, and washed in fantastical tritone palettes. Melmoth forest almost feels like a dream, with the candy-fit yet calming colors making it a woodland of the mind. Or, at least more of the mind than most mediated video game reality. And though the palettes are stylized, they still do a strong job of communicating realistic atmosphere – the first assignment’s bright yellows and greens make for a sunny morning, while the swamp tree area’s dewy early morning hues turn on their head to become sickly and unnatural once you see the extent of Panorama’s damage.

II. The art of squirrel tracking is a thrilling one. Setting up cameras to get a glimpse of a squirrel scampering around the forest in a way that shows you as much information as possible in terms of their path, without necessarily knowing where they’re going next is a scramble of geometry. It’s usually a given you place a camera where the squirrel was right before it left the camera’s view, facing in the direction it was seen going. But the others are much more open. Where is the best place to put the camera in case the squirrel turns? Far out in the direction it was going and hoping it turns before that point? Looking out to wherever you think it will turn? The smug little bastard is probably reveling in your conundrum.

But it’s worth it, to be able to get just that bit farther into the squirrel’s routine and track it down faster. Time isn’t even a thing the game judges you on, just observes. But sometimes, you’ll set up a camera in a lucky position, and fast-forwarding to the end of the tape gives you a snapshot of the squirrel’s activities much farther than you actually are, and you think you furry beast, oh, I’m onto you now.

III. Nuts was played right after Alba, and the different way the two tackled their ecological themes is stark. Alba has you looking at the world through the eyes of a child to communicate her vision of the nature sanctuary that is soon to be a luxury resort, and the plot reflects that with a general kid’s film construction (as is fitting for the game). Nuts has you focusing on the singular task of squirrel tracking as a part of an ecological report to blockade a theme park, which is more grounded in real life ecological efforts.

Unlike Alba, the threat is more than just potential or implied – partway through the game, it’s shown that construction for a dam has already commenced without the ecological sign-off, and in the process destroyed a longstanding tree. Panorama does not stand and menace, it fabricates a version of your report to grant it public construction, and after a massive flood caused by the dam construction, the ATV of a recently MIA colleague of yours is seen in the water along with the box of supplies he usually delivers to you, in a haunting allusion to environmental assassination. As the flood might suggest, there is no triumphant ending where the report is published and Panorama is metaphorically banished to the darkness – though I naïvely believed as much until the very end.

IV. That is not to say NUTS is a game where things go horribly because that’s Real Life, Kid. Not having the plot of a kid’s movie is facile and as unremarkable as having one that is – though, I should note, a well-constructed story about the violence of corporations is a perfectly legitimate one. When I say unremarkable, I mean that wholly neutrally. No, NUTS does something different, and something I think better for the game. As you’ve been separated from your equipment in a squirrel foot hunt gone wrong (in response to Panorama’s false report), your attempt to escape the purgatory valley of rusting car heaps and broken bottles and run-down equipment from a report past becomes more dire with the mounting rain and imminent flood. But not just for yourself – in the days leading up to it breaking out, Nina stresses the importance of making it out not only with your life but your book of research, as the floodwaters will devastate the habitat, potentially permanently for varying reasons. Your work, then, is no longer a means to report, but an essential record of a place that will no longer be, a physical tome to observation of the natural world.

The game ends on a boat you managed to get to, water submerging trees partway, and hills occasionally peaking out from the ripples, uncertain whether the undeniable consequences of the dam will cause backlash strong enough to halt Panorama’s projects or leave the land open for them. But it is not a silent ferry that carries you to through the credits – NUTS, like several games, follows in Portal’s lead with a tune.

It's funny to see how much you've changed

And yet...and yet

To someone else you might look the same

And yet...and yet

We went for a walk,

We took a long walk

My dark blue might look bright to you

And that's your own truth, that is your own truth

Why I see the world differently

That is my own truth, it is my own truth

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Game? Longlist

Even as I use Rapidfire Recs to cover smaller games, and more games in general, there are still experimental, truly tiny games that get skipped in the radar, some of which stretch the definition of game. This game? longlist is an attempt at highlighting those.

Everything here can be found on itch.io, if not elsewhere, and as of the time of writing, everything here is either free or pay-what-you-want. Their playtime is also all under an hour.

1. Sangwich

A micro sandwich-making simulator. Click and drag your various ingredients onto the plate into a tasy arrangement, or get creative. Make a sandwich. Get it classified. Lose cheese slices by accidentally throwing them through the wall.

Windows, Mac

2. Definition of a Ghuest

Two people watch an experimental documentary, in the middle of a highway. In between the film’s exploration of how guests haunt their transient hotels, they talk amongst themselves. A fake film game within a game and a twisting projection of transience.

Windows, Mac

3. Castle Rock Beach, West Australia

A photographer’s recreation of the eponymous location in the Unreal Engine. Just breathtaking to exist and wander around in, and marvel at the spectacle of the photorealism - an aesthetic usually absent from small games.

Windows

4. There Is Never Enough Space!

Short, frenetic, and tactile - a execution-based puzzle game lamenting the constant Sisyphean task that is keeping tidy.

Windows, Browser

5. Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger, and The Terribly Cursed Emerald: A Whirlwind Heist

A comic game about a slapdash bodge-job in the middle of a heist gone wrong - one of the first games I played when exploring the small gamespace, and a staunch favourite.

Windows, Mac

6. blaring rooms

Subtle-toned pixel scenes accompanied by their background noise. Soundscapes that encapsulate the often-muffled score that surrounds us.

Browser

7. Gacha

The gacha machine of growing up. Spend what change you have to get life events in tiered capsules, and see what little stories come about from the memories that machine dispenses. Try to collect them all.

Windows, Mac, Browser

8. Sacramento

A watercoloured washed, illustrative landscape at the edge of a trainstop, from somewhere, to somewhere. A storybook landscape built on the fluidity of water, with softly fading details, where time drifts off to the distance.

Windows, Mac, Linux

9. A Bright Light in the Middle of the Ocean

The cool inside of a lighthouse on an island in the middle of an ocean, against the bright overhead light of day. The clear-cutting sun that makes way for a rolling sunset, before that too, is replaced by the purple-toned night, until morning comes.

Windows, Mac, Linux

10. Orizzonte

An awkward, earnest bit of interactive fiction about the kind of conversations and connections you can strike up with strangers, and how they can grow. It’s built on the short, on the ephemeral, and the worth of both besides.

Browser

11. Joanie

Beautiful scenes of normal life that blend into the surreal, building off of associations, and glimpses of a narrative and a world through a keyhole. Wonderful visuals that speak to memory like poetry - just mind the jank and accidental softlocks.

Windows, Mac

12. TOUCH MELBOURNE

A tactile and comforting game that slices up the act of meeting up with a friend in Melbourne into tiny point-and-click interactions - swiping a bus card, checking the wrapper of an empty bottle, crossing the sidewalk.

Windows, Mac

13. I Cheated On You

Short, tense, and urgent. A one-sided conversation of interactive fiction, about hiding betrayals, and saying everything but what needs to be said.

Browser

14. good morning!

Slice-of-life snapshots of a morning routine, with the pedestrian choices and actions being transformed into minigames. Brings a sense of optimism to the morning I usually do not embody.

Windows, Mac, Browser

15. Interminal

An endless airplane terminal at sunset. Walk the floors and look at the countless little boxed trinkets that are available, look out to the mountains, or watch the planes. Relax in a liminal environment, at a liminal hour.

Windows, Mac

#Gaming#Indie#Video Games#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#Windows#Mac#Linux#Browser#Free#Under an hour#Sangwich#Definition of a Ghuest#Castle Rock Beach West Australia#There Is Never Enough Space!#Dr Lageskov The Tiger and The Terribly Cursed Emerald#blaring rooms#Gacha#Sacramento#A Bright Light in the Middle of the Ocean#Orizzonte#Joanie#TOUCH MELBOURNE#I Cheated On You#good morning!#Interminal

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alba: A Wildlife Adventure & NUTS

This is the first part of a two parter covering the games Alba: A Wildlife Adventure and NUTS. This part is business as usual for the most part – I’m recommending two small games with a common theme. The next part will be me rambling about NUTS and its themes and how it constrasts with Alba, for which spoilers will abound. On with the show.

Alba: A Wildlife Adventure is a photography game about being a young girl who uses documentation of wildlife in order to advocate for the preservation of nature in face of corporate development. NUTS is a puzzle game about engaging in squirrel reconnaissance as a part of a research study in face of megacorporate expansion. I played these two games in succession, and so given their different takes on similar themes, I mentally compared them as I played. And thus comes the report of my little scientific study: they’re good games, Brent.

Alba is a plucky little adventure on the idyllic little island Alba Singh visits every summer to see her grandmother and grandfather. The aesthetic feels a bit like a 3D translation of the modern 2D aesthetic for children’s cartoons – very simplified and geometric but still expressive, with lush scenery and a sunlit colour palette. The only problem is that the derelict wildlife reserve has been slated by the mayor to be destroyed in order to build a luxury hotel as a way of attracting more tourists. So Alba and her friend Inés embark on a quest in order to rejuvenate the reserve and prove the worth of the island’s natural attractions.

For the most part, this involves seeking out and taking photographs of various wildlife species in order to raise people’s interest and awareness of the animals that surround them, but in between that you’re tasked with finding other things – birdhouses and picnic tables to repair, animals trapped in garbage, the source of a curious but dangerous trail of chemical liquid, and so on. These small tasks help build a survey of the various ways the wildlife has declined on the island, and how things can be incrementally improved.

The experience is a cozy one – its plot is almost seemingly from a modern children’s cartoon to match the aesthetic, and carries all the optimism with. Exploring the island and documenting the wildlife makes for a pleasant escapist experience amidst the sense of powerlessness that cane come about with the environmental state of the real world.

However, if you’re looking for something more grounded, NUTS involves being a research team hire sent to the Melmoth forest in order to record squirrels. As it turns out, those furry little scamps are the crux of Professor Nina Scholz’s case against the Panorama corporation and their plans of razing the forest in order to build their amusement park Panoramaland. The forest itself is grand in the height of its foliage and the changes in topography, but the game’s slightly fantastical two-tone aesthetic coupled with the soft field-of-vision fog gives you a sense of cool solitude.

Your part of the research is to track various squirrels by setting up cameras to see where they go in the night, eventually finding their stash of nuts. It’s gradual work over several in-game days – whereas Alba’s method of photographing her world involves a phone camera and a wildlife identification app, the technology in NUTS is steadfastly analog – communication between the player and Nina occurs via fax machine and spiral-corded telephone, and the TVs that send back the recorded footage are delightfully boxy.

But I have to say, the gameplay loop of setting up cameras based on where you saw your target scamper off to the night before, betting on which positions will have the best chances of revealing the most information, seeing the results that night and then relocating the cameras based on that hooked me hard. It had me hot on the trail of whatever squirrels I was supposed to track, all the while I tried to be smarter and more efficient about finding them. The rush that it gave me was similar to the one I had playing the excellent detective game Tangle Tower, despite the fact that it lacks all of the typical mechanics of a detective game.

Of course, given the more grounded presentation and premise of NUTS, the story follows in the same suit. The corporate threat is more than just implied, as this is their second go at funding Panoramaland, and the scars of their influence are stark in the narrative and parts of the landscape of the game. Unlike Alba, it’s not a cozy experience that functions in escapism (or maybe that’s the wrong word, as I’m fairly certain Alba is made for children), but in that, it also functions as a more substantive take on its themes.

Specifications (Alba)

Windows (also Apple Arcade subscription)

$16.99 USD

~5 hours

Specifications (Nuts)

Windows, Mac

$19.99 USD

~6-7 hours

#Gaming#Indie#Video Games#Alba: a Wildlife Adventure#Nuts#Talkin' 'Bout Tiny Games#Windows#Mac#Under 20 dollars#Under 10 hours#Under 5 hours

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stones of Solace

This issue was supposed to come out after the first issue of the two parter I mentioned before, but as it turns out my writing on that two parter was delayed for a time-sensitive longform issue that’s set to come out sometime early 2022, so this issue is coming out early as a break between writing two big issues back-to-back.

Stones of Solace is a cozily fantastical take on what I think I’d tentatively call ‘routine’ games – games that are structured around letting a player play whatever small dish of gameplay it’s served them for the day before preventing any more progress. The previously covered The Sailor’s Dream has routine mechanics, and you’re likely familiar with them being a mainstay of the Animal Crossing games, or in the emotionally rending Bird Alone. (Damn you, George Batchelor!)