#which i of course do because they applaud me for knowing who charlie brown is

Text

.

#hanging out with kids is so funny#if you ever want an undeserved confidence boost literally just hang out with kids and teach them how to do something#like a funny trick with your hands or watch a movie together#because they legit think youre an amazing wizard for the most normal stuff#like me telling my nieces that the characters onscreen were named linus and charlie#they were like HOW DID YOU KNOW THAT#or me knowing the words to the 12 days of christmas#its like well kids the song is actually a couple hundred years old#or reading a book with my cousin and knowing a character's name literally because i read it on the page and he was like 'are you a genius'#also they show you the funniest things as skills like#sitting on the ground and you just have to applaud like its the Olympics#which i of course do because they applaud me for knowing who charlie brown is#p

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

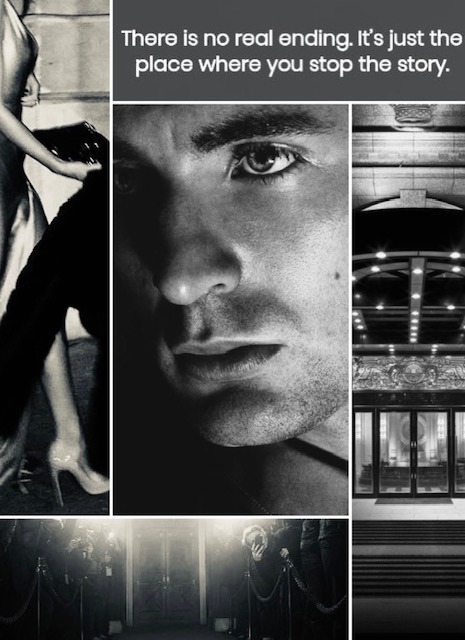

Murder, He Wrote

Epilogue

Summary: You and Ransom attend the launch of his book and the cover closes on your story.

Warnings: Bad language, Mature (NSFW, 18+) NON-CON situations, kidnap, violence. Blood. DO NOT READ IF ANY OF THOSE TRIGGER…READER DISCRETION IS ADVISED…YOU HAVE BEENWARNED.

Pairing: DARK! Ransom Drysdale x Reader

A/N: The end! I can’t believe all this span from @jtargaryen18’s Halloween Challenge last year. I hope you have enjoyed his as much as I have.

Word Count: 3.6k

READ THE WARNINGS!!!! This is a DARK series so don’t @me if you can’t follow simple instructions and end up with butt-hurt. And if you’re under 18 get off my blog!

Disclaimer: This is a pure work of fiction and by writing it does NOT mean I agree with or condone the acts contained within. This fiction is classified as 18+. Please respect this and do not read if you are underage. I do not own any characters in this series bar reader and any other OCs that may or may not be mentioned. By reading beyond this point you understand and accept the terms of this disclaimer.

Murder, He Wrote Masterlist // Main Masterlist.

Part 7

The town car and it's driver took you to whatever swanky hotel Ransom and his publishers had decided upon, you not caring the slightest inwardly, outwardly only half paying attention. You glanced out the window watching the lights of downtown pass by as your husband of merely three weeks held your hand and rubbed the back of it with his thumb.

It was a warm July evening, the two of you dressed to the nines in formal attire. Ransom had insisted the launch be an invite only, formal event. Therefore, he was dressed in a two-piece suit, black of course, with a crisp white button down, silken black tie, and you, you looked like an ice queen's slutty sister. The powder blue silk dress you wore tied together with thin straps on each shoulder, your feet already hurting in your nude six inch sandals. Your free hand tapped a neatly manicured finger over your clutch that matched your shoes. A delicate white gold and diamond tennis bracelet adorned your wrist whilst the necklace you'd been gifted at Christmas hung around your neck. You wore your hair the way he said he loved it, in a ponytail full of waves and wisps framing your face.

After the incident on Valentine’s Day, you’d spent another two weeks in the confines of the basement. All luxuries removed and you were used and abused in exactly the way you had been when Ransom had first taken you, until he’d once more sucked the fight out of you. Only this time you didn’t have the strength to find it again.

You played the part you’d been cast in his sick little fantasy and became totally passive to his whims. You let him fuck you which, in all honesty, wasn’t an entirely unpleasant situation as he knew his way around your body and it felt good. You had given up denying it, and for the moments he was teasing those carnal reactions out of you, you escaped, let yourself imagine you were with someone who you wanted. And by keeping him sweet, you fooled him into thinking you were content. And things settled down, you had that halfway to normal life that you’d achieved before you discovered his manuscript.

But it was bullshit. A means to an end. And you deserved a fucking Oscar.

He’d had the audacity to propose to you, too. In a restaurant. Surrounded by people. He asked you the question, like you had a fucking choice.

Angry, desperate tears had filled your eyes as you’d simply gaped at him, tears the deluded cunt took for you being overwhelmed with happiness. With a smile he slipped the gaudily large diamond on your finger, sealing your fate.

It weighed as heavy on your hand as the grief for your lost life, and the despair at your situation did in your heart.

You’d had a small wedding. Attended simply by your parents and sister. He sent an invite to his mother and father but they didn’t show up. Your dad walked you down the aisle and as you walked towards the man you hated with every breath in your body, your father kissed your cheek and asked you if you were sure you wanted to do this. And no, of course you didn’t, but what could you do?

There was no way out.

“You look as gorgeous tonight as you did on our wedding day.” Ransom’s voice slightly startled you and you turned to face him.

You smiled at him, the smile you knew he wanted to see, as he placed a soft kiss to your cheek before doing the same to your hand, his lips ghosted over the top of the obscene rock and matching band on your finger which caught the lights of the city, sparkling with all the ferocity of a supernova.

Before you needed to reply with some half assed compliment back, the town car stopped as the driver got out and opened Ransom's door.

"Wait here," he instructed and walked around with the driver on the other side, escorting you out the minute your own door opened.

Flashbulbs fired off in your eyes, no doubt the press there for some absolutely ridiculous notion that this book was anything but its true nature of terror and disgust.

Ransom’s hand pressed into the base of your back as he guided you along in front of him, various members of the press calling his name, and you heard the excited shouts from some as they spotted the bands on both yours and Ransom’s hands, positively shrieking as they asked when you’d gotten married.

The headlines flashed in your mind now, 'Grandson of the Great Harlan Thrombey Releases First Suspense Novel'. 'One of Boston's Most Notorious and Eligible Bachelors is Strictly Off The Market' . 'Trust Fund Playboy Sinks His Bunny'.

It made you want to puke.

In fact, as the press line faded and you stepped foot into the lobby, you swallowed back the bile forcing its way up. A tray with champagne flutes passed you by and you immediately snagged one.

When Ransom had been distracted for a brief moment, you quickly glanced around and swallowed back the entire flute of the bubbly drink. Delightfully enjoying the brief taste and quick head rush it gave you.

The further you walked into the event, his hand still against your bare back, the louder it grew and the more trays of champagne and appetizers were floating by.

As typical, the two of you were fashionably late so, you had little chance to take part in any nibble or further, a drink, because the supposed "man of the hour", more like terror of life, was due to give a speech.

His agent pulled the two of you aside and made mention that it was time for Ransom to greet his guests. He pressed a sickening sweet kiss to your lips and confidently took to the small podium atop a small stage nearby.

“First and foremost, thank you to everyone who came out tonight. But more importantly, thank you to my beautiful wife, without you Sweetheart, this wouldn't be possible.”

The smile he flashed you was loaded with meaning as the pair of you looked at one another, his eyes shining with the depraved private understanding you shared.

And you hated him then just about as much as you ever had.

Excited muttering spread around the room as he had knowingly referred to you as his wife. It was the first time he’d announced your marriage to the world but, as he smiled and held his hands up, nodding smugly and confirming whatever people were asking him, you felt nothing but an overwhelming sense of nausea. To everyone else it was a sweet dedication, to you it was a sickening truth. This book was based on what he’d done to you. What he was saying was literal truth.

And the fact that the people currently applauding whatever he had said would never realise the true nature of those words on the pages of his book made you want to vomit in your handbag.

Applause rang around the room and you realised everyone was turned in your direction. Drawing your shoulders back you stood tall and once more fixed that fake smile on your face before Ransom cleared his throat and began to speak again.

But you didn't listen, you drowned him out, the sound of his voice distant and murky like Charlie Brown's teacher. You allowed you mind to think of anything but the present, other than the fact that these people were in unknowing full support of the hell you'd been through the last nine months.

Eventually a loud, rapturous applause signalled the end of his speech and he stepped back, smiling and then turned to the man from his publishers who shook his hand furiously, before the pair of them posed for photos.

That was when he beckoned you to him, looking at you in such a way that made your skin crawl and your teeth seethe with each breath. This bastard expected a photo op from you above all this, commemorating this disaster.

On autopilot you headed towards him, indifference obedience now your specialty and his arm curled possessively round your waist, fingers splaying on your hip. You posed and smiled as the flashes went off, but as you stole a glance at the large, ornate clock on the wall, you suddenly felt your head beginning to swim.

Seeing a convenient way out of this bullshit, you made sure to falter just a little, placing your hand to your chest. It caused Ransom's attention to turn to you.

"Sweetheart, are you alright?"

“I’m feeling a little light headed and warm.” You looked up at him. “Could we maybe get some air?”

"Sure, yeah," he looked to his agent and they nodded towards a side door in the room.

His arm still round you, playing the doting husband, he led you towards it and opened it with a flourish, allowing you to step out in front of him.

You emerged into the alley at the side of the building and took a huge gulp of air, steadying yourself.

"Y/N, what's wrong?"

You were warm, flushed, your skin tingling as the now cooling air hit your slightly damp skin, your nipples perking at the temperature change were visible through the silk dress, and you didn’t miss the heated glance he gave them as you spoke. "I, I don't know. I think it's all the commotion."

“You do look a little flushed.” His eyes moved back to yours and he studied you for a moment, his large hands gently cupping your face as he kissed your forehead before his lips pressed to yours. “Wanna take a walk?”

Despite the fact you really couldn’t walk far in the ridiculous shoes you were in, you nodded. Anything to avoid going back in there and listening to all those sycophants kissing his ass.

He took your hand and started walking slowly down the alley. You were mid-way down when a man jumped out from behind the dumpster. You screamed and instinctively Ransom jumped to the side, pulling you slightly behind him.

“Give me the money and the jewellery, no one gets hurt.” The man spoke gruffly and you felt Ransom draw himself up to his full height as he glared at the dirty, dishevelled man, disdain on his face.

“Eat shit.”

“Ransom, just... please give him what he wants.” Your voice trembled as your body shook, your right hand already removing the rings on your left.

“I’d listen to your pretty wife, if I were you.” The man spoke as he reached into his pocket and when he withdrew his hand you swallowed at the unmistakable flash of metal.

“Fuck, Ransom, he’s got a knife!” You clutched his arm. “Please just give it to him!”

"Fuck, no," he started reaching for his phone but the man lunged toward him.

In the melee that followed, you were thrown to the side, your rings clanging to the floor somewhere along with your clutch, your palms and knees scraping painfully on the floor. By the time you’d pushed yourself up, you saw the man scrambling to his feet, Ransom’s watch and wallet in his hand. He turned to look at you and you backed away, stumbling once more to the ground letting out a blood curdling scream as he advanced. He stopped, picked up your rings and your bag, before he turned, bolting up the alley and rounding the corner, disappearing from sight.

"Y/N," the croaking voice came from your husband as he staggered towards you, a deep red seeping through his white dress shirt, his one hand attempting to stave off the bleeding. The other, cradling his phone. But he didn't get more than a few steps as he collapsed nearby.

"Ransom!" You shrieked and heels be damned, you ran to him, looking around, "help!"

"Call 9-1-1, Baby," he begged, trying to thrust the phone into your hand and you leaned over him.

With a jittery hand you swiped over to the emergency call option and hit the first two digits before you glanced around again and hesitated, rising slowly to your feet.

“What...” Ransom’s chest heaved as he looked up at you, his face white with shock as you turned the phone in your hand and shrugged.

“Yeah, you see, I could call for help but...” with that you tossed his phone to the hard ground and crunched it with your stupidly high heel, rotating your foot to make double sure, the glass and metal grinding between the stiletto and the tarmac. “Whoops, looks like it got smashed in the fight.” You gave a little chuckle. “And of course, mine was in my bag which he took. Isn’t that ironic? I mean the first time you permit me to use it for something other than to contact you or my mom, I can’t.” You made a little tutting noise. “Guess I’ll just have to keep yelling and hope someone hears.”

With that you turned and screamed, a frantic yell. “Please, someone help us! Please, he’s been stabbed, call 9-1-1.” You slowly dropped back to a kneel, ignoring the sting of your grazed knees and smirked. “Dammed, I really am good at this acting shit, don’t you think, handsome?”

Ransom coughed a harsh and wet cough. His chest heaving raggedly as he struggled between catching a breath and bleeding out.

“Y/N...” he spluttered, “you...please...”

"So many criminal junkies in Boston, Sweetheart. Plenty who will take the fall for a little hit,” you emphasised the 't' of the last word as you spoke the very same line that he had delivered to you months ago, the threat he had held over you and used to keep you in check whenever you stepped over that line.

His eyes widened further as the realisation set in, you could see his brain working and it gave you a buzz, a sense of satisfaction to know that he understood this was your doing.

You wanted the last thing this bastard thought about to be how you were responsible for his death. But more so, his narcissistic and sociopathic tendencies be damned, you wanted him to completely understand exactly how it was his fault.

And given the way he was bleeding and struggling for breath, you didn’t have long.

Another scream for help flew from your mouth as you pressed one hand on top of his which were now both clutched to the wound in his stomach, the other brushing his hair back slightly as you smiled down at him.

“I told you when you threw me back in the basement that the way you treat people would come back to haunt you.” You gave a little shrug. “And, when you told the homeless guy looking in the bins on collection day a few months back to eat shit and get a job, well, he took it kinda personally. He didn’t even blink when I asked how much it would take to knock you off.”

"You..." choking on blood, "vicious..." choke,

At that you gave another loud hysteric yell for help before you turned your head back to look at him.

“See, once upon a time I thought you’d changed. But here’s the thing, a person like you doesn’t change, Hugh. You’re incapable of love. You take what you want when you want for no reason other than it pleases you.”

Another scream for help, and this time you could hear someone answering and a lot of yells as people started running towards you.

“Well, now I’ve taken your life like you took mine.” You bent down, your forehead pressing to his as you smirked. His arm reached up to grab you, his blood soaked hand curling over your cheek and side of your neck. "And you know what? It feels good."

His palm was warm and slick against your skin and his eyes blazed with anger as his fingers squeezed. You knew he was desperately trying to hurt you but you felt nothing. You smiled, as you placed a soft kiss to his lips, your words whispered as you pulled back ever so slightly. “Karma’s a bitch, and so am I. See you in hell.”

As the fake tears started to pool in your eyes once more, you allowed your lip to tremble for distraught emphasis. Blood was now trickling out of Ransom's mouth, along down his ear and to the tarmac. You pulled back just a little so as to see his eyes. You wanted to watch him choke on his own blood as he took that final breath. You started sputtering words incoherently as you amped up the hysteria, hearing the footfalls now just behind you.

He didn’t even make it to the hospital.

Hugh Ransom Drysdale was pronounced dead at 21:05 hours on Friday 17th July where he lay in a pool of his own blood, in that dark alleyway down the side of the hotel.

Leaving you a widow.

And free.

***10 months later***

It was as simple as it sounded, closing your eyes and pointing to a spot on a map. Your finger ended up on Boulder.

Colorado was far enough from the last year or so of your life that you could feel comfortable. You'd researched it, finding it to be something worth interest. Affordable. Breath-taking scenery. Incredible life altering activities and quaint little towns. The summers were supposedly warm but rarely did the temperature rise above ninety-five, the winters were supposedly very cold, dry and windy; rarely dropping below six degrees with partly cloudy skies year round.

The months following Ransom’s death had been as draining as humanly possible. The investigation had involved countless interviews before the police and authorities settled for it being a mugging gone wrong. But then there had been the months of wrangling and private law cases his parents had attempted to bring against you to prevent you getting his money, despite the probate law being fairly simple. You were married. He left no will. It was yours by default.

Eventually, when the Drysdales had exhausted every last option, they were forced to concede and that was when you made the decision to leave, a decision of which your parents were highly encouraging. They practically talked you into this whole thing to begin with. Helping you leave your nightmares behind. Despite them not suspecting anything at first, you weren't blind to the fact that things still had not sat right with them. You knew they had suspected a level coercion, that maybe you'd had a manic episode of mental illness, but you never had divulged the full details and by the time he was gone, they hadn't cared. Your relationship with them had strengthened and healed and that was what you cared about.

Now, you were newly nestled in Boulder with a great condo downtown, a stone’s throw from the historic district that was filled with cliché shops and bars. Whilst you didn’t need the money, you’d taken a job working in the media department of a private law firm. It was a far cry from your journalist days, but it suited you just fine.

The more distance you put between who you were now and who you had been, the better.

You were at peace.

The May evening air was temperate as you crossed the street and opened the door to the designated bar in which you were meeting your new group of friends, mostly gathered from work, for a girl's night out. You’d been held up a little in the office so they were already waiting at a table. You waved and gestured to the bar, indicating you were going to get a drink.

As you sidled up to the wooden counter, you were jolted a little into a man to your right. You turned to apologise and gave a little double take. You recognised him instantly. But you didn’t want to make that obvious and cause him to feel uncomfortable. You knew how it felt, to have everyone looking at you, hushed whispered comments as you went about your business, people trying to figure out if you were who they thought you were.

That was part of the reason you had moved, and you sure as hell weren’t about to subject the man next to you to the same, uncomfortable experiences.

Recovering quickly, you hastily apologised and he smiled.

“Don’t worry about it.” His Boston accent was evident and you smiled.

“I miss that accent.”

The man chuckled, his warm blue eyes creasing slightly as he looked at you. “You from Boston, too?”

“Concord.”

“Newton.” He replied, “well, I lived there anyway, but I’m sure you already knew that.”

You wrinkled your nose. “Should I? Know that, I mean?”

He studied you for a moment, and you kept your face as passive as possible. You could tell he knew that you knew, but you gave a shrug none-the-less and he smiled, a gorgeous smile that lit up his entire face, perfect white teeth flashing from beneath an immaculately groomed beard, as he extended his arm towards you.

“Andy Barber.” His fingers gently brushed the back of your knuckles, as you shook his hand, his grip warm and gentle.

“Oh, of course.” You smiled back. “One of our attorneys.”

“Our?”

“Yeah, sorry, I’m Y/N. I work in the media department. I mean I only started a few weeks ago but...”

“Well, in that case, I’m pleased to meet you, Y/N, and welcome aboard.” His smile didn’t falter as he let go of your hand and gestured to the bar. “Can I get you a drink?”

You paused for a moment before you took a deep breath.

And nodded.

“Sure, that’d be great.”

******

Sequel: Follow Andy and reader’s story in Consciousness Of Guilt.

#murder he wrote#dark ransom drysdale#dark ransom drysdale x reader#dark ransom x reader#dark ransom drysdale x you#ransom drysdale#ransom drysdale x reader#ransom drysdale x you#ransom drysdale fic#chris evans#chris evans characters

342 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good grief, Charlie Brown.

I’ve never owned an electric toothbrush. I’ve never had a dishwasher. I am the dishwasher. I like washing dishes. I never bought an iron. I don’t have a hairdryer. I find it strange that I get advertised these reusable alternatives for things that I never use anyway. Alternatives to cling film. I put another plate over the dish. Alternatives to cotton buds. I use my finger. (Ew, you may say, but surely a finger’s that size to fit in ears and nostrils? Or whatever orifice you please. Wash your hawnds.) Alternatives to cotton wool circles. What? I dont know why these thoughts have come into my head, when I want to write about my youngest child. Really, I’m meant to be working, but an annoying email from my dead daughter’s school sent me down a suicide rabbithole. Perhaps those other thoughts come about as my classic brain avoidance schemes. Like when you hoover instead of doing an essay. Positive procrastination, I used to call it. I wanted to visit some friends last night- a fun thing! but I was feeling all solitary and awkward. I cleaned the bathroom ceiling at first, instead! I had to really talk myself into going to see them. I was looking at my bed and it was saying, “Get into me! and read your book!”

Then I went, and I had a lovely time, of course. I still finished the book I was reading, when I got home at midnight, until three am, making myself ever so tired. I’ve stopped taking the tablets- beta blockers and mirtazapine (more by accident rather than design. They’re still up in the chemist waiting for me. I’m rather disorganised) and so sleep doesn’t come as readily. I have to take deep breaths for ages sometimes, to get over. And I awake in the night hearing things that aren’t there. I heard The Woodcarver calling me, one night, plain and loud as day. Another time, I heard my son knocking my door three times, sharply (or was it a burglar? I said that to someone and they laughed. Burglars don’t knock! Oh, hello there, wake up, I’m robbing you blind!) Bounced out of bed. Heart hammering. Called him. He was fast asleep. Was it her ghost? I don’t believe in ghosts, really. Kind of wish I did. She’d be a mischievous one, no doubt. Is it always 5:57am, when I awake? The same time. Time to find your dead child.

I’m often in the house alone, now. They didn’t want to leave me alone, and there were so many people in the house, for ages. Then all of a sudden, it stopped. And I changed lovers... I changed to the one I’d been in love with for over a year, the one who seemed too young, the one who wasn’t interested. Suddenly he was interested. Well. It wasn’t sudden. It took a few weeks. Seven weeks? The seven week itch? It coincided with when the Scottish lover asked me to stop letting other people come to the house. He wanted me to himself. Which is kind of fair enough, though I knew it wouldn’t last anyway. (People coming to my house, I mean, not the relationship. I really enjoyed having a relationship with him. He is very sweet, funny, intelligent, and kind. The sex was great. He can cook wonderful food and play guitar well. I liked to sing with him. I am ashamed to say I was bothered by his being smaller than me, though. His face tended to itch me, too- he never quite grew a beard long enough to stop that. As he kept shaving it off, not because he couldn’t. That was the first time he kind of annoyed me, though.)

Lockdown doesn’t help, of course. We were all breaking rules in our grief. Covid is cancelled, my mother said. Masks off. Hugs all round. A friend told me you need extra oxytocin when you’re grieving. I was getting plenty of it. Good grief...

Now I am frequently alone, and as my new lover is very busy studying (or perhaps less interested in me again now that he has my attention back? Though his reticence in getting with me stemmed from his concerns about the uneven nature of our interest in each other...) I haven’t seen him all week. I feel myself becoming depressed, and withdrawn, and paranoid, yet I still don't feel particularly sad about my daughter’s death. Which is strange. Isn’t it? Here is the email I received from her school this morning (it had her name and class at the top of the email):

“Good morning

I hope this email finds you all well.

A number of years ago I signed the college up to the campaign against period poverty. I receive and distribute sanitary products to girls, primarily on free school meals, but any who are in need of the products and either can’t afford them or it is difficult to get them. The products are normally distributed by myself, during P.E and games, unfortunately this can’t happen at present.

These products are still available during the school closure. If you wish to avail of them, please contact our school info account (which is only read by one member of office staff) your request will be directed to me and I will contact you directly regarding collection.

These are difficult times for many at present and to quote my favourite supermarket, ‘every little helps’.

Kind regards...”

I was really with her until she quoted Tesco. And said they were her favourite!! Ugh! I mean, it really is a great idea. Though they really should check if the people they are writing about are still capable of bleeding. My heart bleeds....

I replied thus:

“Hello there.

Great idea, but as (my youngest daughter) has died, she won't be needing them any more. I hate Tesco- they ruin many little businesses.

Maybe take me off this mailing list?”

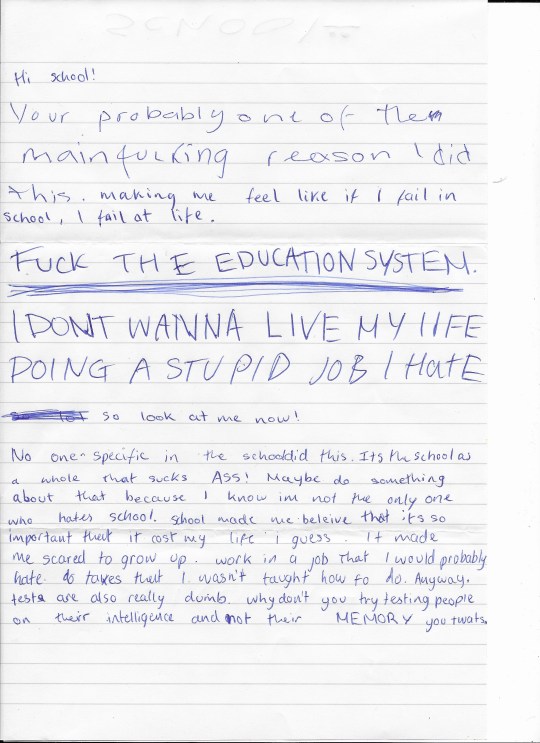

Then I attached one of her seven suicide notes: the one for school. Which I had previously not shown them. I only found it on Christmas Eve. Can I attach it, here? It has no names...

There we are. Is it wrong of me to find her notes amusing? She is so angry, people say. I wonder how much of it is literal, and how much of it is using the school as a big nameless scapegoat. She was funny in the rest of them, too, and very loving. I found them comforting, like a fucked up Christmas present.

Then I started reading articles about suicide, and they were about how we shouldn’t call the people who do it selfish, about how depressed they are, how they need pity, not anger. I’m tired of the pity (though I’m not the suicidal one). I’m not producing enough sadness from myself when people pity me, either. Where is my sadness? Am I too acceptant of it all? We are all going to die. Is suicide like a C-section? Is it cheating death, like I thought my Caesareans cheated birth? Is suicide self euthanasia? Why do I not miss my daughter more? Is it because she had already left? Was she released, happy, free as a bird, swooping away on an Awfully Big Adventure? Trapezing her way into the æther? I googled to see if I could find any positive reactions to suicide. Is this my nature, to try and find the good in everything? To try and make light of the horrific? Is everything a joke to me?

I found this blog post, from Andreas Moser.

I love it. Am I trying to take the blame away from myself? The NHS? The school? Should I be reeling and railing against the systems that let my daughter get into that state? Why am I instead trying to find ways to applaud her behaviour, accept it, even enjoy it?! When I read his words, “I admire their courage (because logical as it may be, it’s not easy) and the determination to make the ultimate decision in life oneself.” I felt a strange sensation of relief, that someone else could think those things. I had been thinking them, but trying not to, because it seemed like such an awful thing to think. But then I think, why does anyone else have to be to blame? It was her decision.

The book I was rereading is called Life After Life, by Kate Atkinson. It’s my favourite book, I have decided, for now. Do favourites stay favourites? I was looking at my old Couchsurfing Profile today (because of Andreas’ blog- he, as a hippy hermit, is, of course, on Couchsurfing). One needs to update these every so often. Explain that you have watched another film in the last twenty years, that there is one less sofa in your living room, one less child on your earth. Even though no-one is allowed to move around, really. No visiting. No exploring. Perhaps she killed herself to escape the boredom.

In Life After Life, the main character, Ursula, lives again and again. (I forgot that to live again and again, she had to die again and again. It's a very sad and graphic book, spanning two wars- read it. It is, ultimately, uplifting.) I wanted to read it again to make my daughter live again, and again. We need to write her alive. Show her drawings and paintings. Listen to her songs (they're hilarious). Read her poems. Admire her photographs. Tell the stories of her antics.

I know that really she was actually depressed and withdrawn. I know it isn’t a glorious escape. That her wee head was broken, and that sometimes it’s just easier to say, it was unfixable, she was determined, this is what she wanted, than to contemplate it as my (or anyone else’s) failure to help her. I know that she used to be confident and gregarious. She would have danced in front of people, inspiring others. She was always upside-down, tumbling, twirling, cartwheeling. She had a dry, cheeky wit, and rather an amusing obsession with poo and wee. She was kind, and wise. She liked to bake vegan treats. She could draw, and paint, and sing so beautifully. She played the ukelele, but by then she was hiding away. She had started to write poems- songs? She wouldn’t show us them. We had to beg her to perform on the trapeze for her Granny’s eightieth, in July. She did so, beautifully, but you could tell she hated the attention. Four months later, she hanged herself on it.

Had we all withdrawn into ourselves, this 2020? Was there really nothing else to do? Yet I remember the start of Lockdown seeming idyllic. All that free time, all that sunshine. Was I just trying to convince myself, as usual? The only people we saw were the Woodcarver and the neighbours. She taught the wee boy next door to ride his unicycle. When she died, he brought in a picture he had drawn, of them on their unicycles, she as an angel above herself, a rainbow arcing over the three figures. His sadness affected me. I felt like I could only be sad through other people. Where is my sadness? Where is my grief? Good grief, bad grief, no grief? Alternatives to grief.

1 note

·

View note

Text

1994 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting (Morning) Transcript

1. Bigger meeting venue needed next year

WARREN BUFFETT: Put this over here.

CHARLIE MUNGER:

WARREN BUFFETT: Am I live yet? Yeah.

Morning.

AUDIENCE: Morning.

WARREN BUFFETT: We were a little worried today because we weren’t sure from the reservations whether we can handle everybody, but it looks to me like there may be a couple seats left up there.

But I think next year, we’re going to have to find a different spot because it looks to me like we’re up about 600 this year from last year, and to be on the safe side we will seek out a larger spot.

Now, there are certain implications to that because, as some of the more experienced of you know, a few years ago we were holding this meeting at the Joslyn Museum, which is a temple of culture. (Laughter)

And we’ve now, of course, moved to an old vaudeville theater. And the only place in town that can hold us next year, I think, is the Ak-Sar-Ben Coliseum where they have keno and racetracks. (Laughter)

We are sliding down the cultural chain — (laughter) — just as Charlie predicted years ago. He saw all this coming. (Laughter)

2. Buffett loses “Miss Congeniality” title to Munger

WARREN BUFFETT: Charlie — I have some rather distressing news to report. There are always a few people that vote against everyone on the slate for directors and there’s maybe a dozen or so people do that. And then there are others that single shot it, and they pick out people to vote against.

And, this will come as news to Charlie, I haven’t told him yet. But he is the only one among our candidates for directors that received no negative votes this year. (Applause).

Hold it — hold it. No need to applaud.

I tell you, when you lose out the title of Miss Congeniality to Charlie, you know you’re in trouble. (Laughter)

3. Meeting timetable

WARREN BUFFETT: Now, I’d like to tell you a little bit how we’ll run this. We will have the business meeting in a hurry with the cooperation of all of you, and then we will introduce our managers who are here, and then we will have a Q&A period.

We will run that until 12 o’clock, at which point we’ll break, and then at 12:15, if the hardcore want to stick around, we will have another hour or so until about 1:15 of questions.

So, you’re free to leave, of course, any time and I’ve pointed out in the past that it’s much better form if you leave while Charlie is talking rather than when I’m talking, but — (Laughter)

Feel free anytime, but you can — if you’re panicked and you’re worried about being conspicuous by leaving, you will be able to leave at noon.

We will have buses out front that will take you to the hotels or the airport or to any place in town in which we have a commercial interest. (Laughter)

We encourage you staying around on that basis.

4. Berkshire directors introduced

WARREN BUFFETT: Let’s have the — let’s get the business of the meeting out of the way. Then we can get on to more interesting things.

I will first introduce the Berkshire Hathaway directors that are present in addition to myself and —

First of all, there’s Charlie, who is the vice chairman of Berkshire, and if the rest of you will stand.

We have Susan T. Buffett, Howard Buffett, Malcolm Chase III, and Walter Scott Jr. And that’s it. (Applause)

5. Meeting quorum

WARREN BUFFETT: Also with us today are partners in the firm of Deloitte and Touche, our auditors, Mr. Ron Burgess and Mr. Craig Christiansen (PH).

They are available to respond to appropriate questions you might have concerning their firm’s audit of the accounts of Berkshire.

Mr. Forrest Krutter, secretary of Berkshire. He will make a written record of the proceedings.

Mr. Robert M. Fitzsimmons has been appointed inspector of election at this meeting. He will certify to the count of votes cast in the election for directors.

The named proxy holders for this meeting are Walter Scott Jr. and Marc D. Hamburg.

Proxy cards have been returned through last Friday representing 1,035,680 Berkshire shares to be voted by the proxy holders as indicated on the cards. That number of shares represents a quorum and we will therefore directly proceed with the meeting.

We will conduct the business of the meeting and then adjourn to the formal meeting — and then adjourn the formal meeting. After that, we will entertain questions that you might have.

First order of business will be a reading of the minutes of the last meeting of shareholders.

I recognize Mr. Walter Scott Jr. who will place a motion before the meeting.

WALTER SCOTT: I move that the reading of the minutes of the last meeting of the shareholders be dispensed with.

WARREN BUFFETT: Do I hear a second?

VOICES: Seconded.

Motion has been moved and seconded. Are there any comments or questions? Hearing none, we will vote on the motion by voice vote. (Laughter)

All those in favor say aye.

VOICES: Aye.

WARREN BUFFETT: Opposed? The motion is carried and it’s a vote.

Does the secretary have a report of the number of Berkshire shares outstanding entitled to vote and represented at the meeting?

FORREST KRUTTER: Yes, I do. As indicated in the proxy statement that accompanied the notice of this meeting that was sent by first class mail to all shareholders of record on March 8, 1994, being the record date for this meeting, there were 1,177,750 shares of Berkshire common stock outstanding, with each share entitled to one vote on motions considered at the meeting. Of that number, 1,035,680 shares are represented at this meeting by proxies returned through last Friday.

6. Directors elected

WARREN BUFFETT: Thank you. We will proceed to elect directors.

If a shareholder is present who wishes to withdraw a proxy previously sent in and vote in person, he or she may do so.

Also, if any shareholder that’s present has not turned in a proxy and desires a ballot in order to vote in person, you may do so.

If you wish to do this, please identify yourself to meeting officials in the aisles who will furnish a ballot to you.

Would those persons desiring ballots please identify themselves so that we may distribute them? Just raise your hand.

I now recognize Mr. Walter Scott Jr. to place a motion before the meeting with respect to election of directors.

WALTER SCOTT: I move that Warren Buffett, Susan Buffett, Howard Buffett, Malcolm Chase, Charles Munger, and Walter Scott be elected as directors.

WARREN BUFFETT: Is there a second?

VOICE: Seconded.

WARREN BUFFETT: It’s been moved and seconded that Warren E. Buffett, Susan T. Buffett, Howard G. Buffett, Malcolm G. Chase III, Charles T. Munger, and Walter Scott Jr. be elected as directors.

Are there any other nominations? Is there any discussion? Motions and nominations are ready to be acted upon.

If there are any shareholders voting in person, they should now mark their ballots and allow the ballots to be delivered to the inspector of elections.

Seeing none, will the proxy holders please also submit to the inspector of elections the ballot voting the proxies in accordance with the instructions they have received.

Mr. Fitzsimmons, when you’re ready you may give your report.

ROBERT FITZSIMMONS: My report is ready. The ballot of the proxy holders received through last Friday cast not less than a 1,035,407 votes for each nominee.

That number far exceeds a majority of the number of all shares outstanding and a more precise count cannot change the results of the election.

However, the certification required by Delaware law regarding the precise count of the votes, including the votes cast in person at this meeting, will be given to the secretary to be placed with the minutes of this meeting.

WARREN BUFFETT: Thank you, Mr. Fitzsimmons.

Warren E. Buffett, Susan T. Buffett, Howard G. Buffett, Malcolm G. Chase III, Charles T. Munger, and Walter Scott Jr. have been elected as directors. (Applause)

7. Formal meeting adjourns

WARREN BUFFETT: Does anyone have any further business to come before this meeting before we adjourn?

If not, I recognize Mr. Walter Scott Jr. to place a motion before the meeting.

WALTER SCOTT: I move the meeting be adjourned.

WARREN BUFFETT: Second?

VOICES: Seconded.

The motion to adjourn has been made and seconded. We will vote by voice. Is there any discussion? If not, all in favor say aye?

VOICES: Aye

WARREN BUFFETT: Opposed say no, the meeting is adjourned. (Laughter)

It’s democracy in Middle America. (Laughter)

8. Berkshire managers introduced

WARREN BUFFETT: Now, I’d like to introduce some of the people that make this place work to you. And if you would hold your applause until the end because there are quite a number of our managers here.

I’m not sure which ones for sure are here, some of them may be out tending the store as well.

But, first of all, from Nebraska Furniture Mart, Louie, Ron, and Irv Blumkin. I’m not sure who’s here, but would you stand please, any of the Blumkins that are present?

OK, we’ve — looks like Irv. I can’t quite see it.

From Borsheims, is Susan Jacques here? Susan? There she is. Susan had a record day yesterday. She just — (applause) — Susan became CEO just a few months ago and she’s turning in records already. Keep it up. (Laughter)

And from Central States Indemnity, we have the Kizers. I’m not sure which ones are here, but there’s Bill Sr., Bill Jr., John, and Dick.

Kizers, stand up. I think I can see him — John.

Don Wurster from National Indemnity.

Rod Eldred from the Homestate Companies.

Brad Kinstler from Cypress, our worker’s comp company.

Ajit Jain, the big ticket writer in the East.

And Mike Goldberg, who runs our real estate finance group and also generally oversees the insurance group. Mike.

Gary Heldman from Fechheimers.

Chuck Huggins from See’s, the candy man.

Stan Lipsey from the Buffalo News.

Chuck’s been with us, incidentally, twenty-odd years. Stan’s been working with me for well over 25 years.

Frank Rooney and Jim Issler from H.H. Brown.

Dave Hillstrom from Precision Steel.

Ralph Schey from Scott Fetzer.

Peter Lunder, who is with our newest acquisition, Dexter Shoe. And Harold Alfond, his partner, couldn’t be with us because his wife is ill.

And finally, the manager that’s been with Charlie and me the longest, Harry Bottle from K&W. Harry, you here? There’s Harry.

Harry saved our bacon back in 19 — what? — 62 or so, when in some mad moment I went into the windmill business. And Harry got me out of it. (Laughter)

That’s our group of managers and I appreciate it if you give them a hand. (Applause)

9. Midwest Express adding flights to Omaha

WARREN BUFFETT: I have one piece of good news about next year for you.

In addition to moving to larger quarters, they’re going to add nonstop air service from New York, Washington, and Los Angeles here in the next few months, Midwest Express.

So, I hope they do very well with it and I hope that makes it easier for you to get into town.

10. Q&A logistics

WARREN BUFFETT: Now, in this — for the next two hours and 15 minutes or so, we’ll have a session where we will take questions.

We have seven zones, three on the main floor. We’ll go start over there with zone one and work across.

On the main floor, if you’ll raise your hand, the person who is handling the mic will pass it to you and we’ll try to not repeat any individual in any one zone till everyone in that zone has had a chance to ask one question. So, after you’ve been on once, let other people get a shot.

When we move up to the loge, we have one person there and in the case — and then we have three in the balcony, which is essentially full now.

And we would, up there, we would appreciate it if you would you leave your seat and go to the person with the mic. It’ll be a little easier in both the loge and the balcony to handle it that way.

And if you’ll go a little ahead of time, that way if there’s a line of two or three you can you can line up for questions in both the loge and balcony.

So, whatever you’d care to ask. If you want an optimistic answer you’ll, of course, direct your question to Charlie. If you’d like a little more realism you’ll come to me and — (laughter).

11. Derivatives: dangerous combination of “ignorance and borrowed money”

WARREN BUFFETT: Let’s start over in zone 1.

Sometimes we can’t see too well from up here, but —

In fact, I can’t even see the monitor right now, but do we have one over there?

And if you’ll identify yourself by name and your hometown, we’d appreciate it.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: My name is Michael Mullen (PH) from Omaha.

Would you comment on the use of derivatives? I noticed that Dell computer stock was off 2 1/2 points Friday with the loss of derivatives.

WARREN BUFFETT: Question is about derivatives. We have in this room the author of the best thing you can read on that. There was an article in Fortune about a month ago or so by Carol Loomis on derivatives, and far and away it’s the best article that has been written.

We also have some people in the room that do business in derivatives from Salomon.

And it’s a very broad subject. It — as we said last year, I think someone asked what might be the big financial story of the ’90s and we said we obviously don’t know, but that if we had to pick a topic that it could well be derivatives because they lend themselves to the use of unusual amounts of leverage and they’re sometimes not completely understood by the people involved.

And any time you combine ignorance and borrowed money — (laughter) — you can get some pretty interesting consequences. (Laughter)

Particularly when the numbers get vague. And you’ve seen that, of course, recently with the recent Procter and Gamble announcement.

Now, I don’t know the details of the P&G derivatives, but I understand, at least from press reports, that what started out as interest rate swaps ended up with P&G writing puts on large quantities of U.S. and, I think, one other country’s bonds. And any time you go from selling soap to writing puts on bonds, you’ve made a big jump. (Laughter)

And it — the ability to borrow enormous amounts of money combined with a chance to get either very rich or very poor very quickly, has historically been a recipe for trouble at some point.

Derivatives are not going to go away. They serve useful purposes and all that, but I’m just saying that it has that potential. We’ve seen a little bit of that.

I can’t think of anything that we’ve done that would — can you think of anything we do that approaches derivatives, Charlie? Directly?

CHARLIE MUNGER: No. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: I may have to cut him off if he talks too long. (Laughter)

Is there anything you would like to add to your already extensive remarks? (Laughter)

CHARLIE MUNGER: No. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: OK.

12. Berkshire participated in Cap Cities stock buyback

WARREN BUFFETT: In that case we’ll go to zone 2. (Laughter)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: My name is Hugh Stevenson (PH). I’m a shareholder from Atlanta.

My question involves the company’s investment in the stock of Cap Cities. It’s been my understanding in the past that that was regarded as one of the four, quote unquote, “permanent” holdings of the company.

So I was a little bit confused by the disposition of one million shares. Could you clarify that? Was my previous misunderstanding — was my previous understanding incorrect? Or has there been some change or is there a third possibility?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, we have classified the Washington Post Company and Cap Cities and GEICO and Coke in the category of permanent holdings. And —

But in the case of three of those four, The Washington Post Company, I don’t know, maybe seven or eight years ago, GEICO some years back, and now Cap Cities, we have participated in tenders where the company has repurchased shares.

Now the first two, the Post and GEICO, we participated proportionally. That was not feasible, and incidentally, not as attractive taxwise anymore.

The 1968 Tax Act changed the desirability of proportional redemptions of shares, from our standpoint. That point has been missed by a lot of journalists in commenting on it, but it just so happens that the commentary that has been written has been obsolete, in some cases, by six or seven years.

But, we did participate in the Cap Cities tender offer, just as we did in the Post and GEICO.

We still are, by far, the largest shareholder of Cap Cities. We think it’s a superbly run operation in a business that looks a little tougher than it did 15 years ago, but looks a little bit better than it did 15 months ago.

Charlie, you have anything?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Uh, no. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: He’s thinking it over now though before — (Laughter)

13. Unlikely we’d buy company with no current cash flow

WARREN BUFFETT: Zone 3.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Good morning. My name is Howard Bask (PH) and I’m from Kansas City. And I’ve got a theoretical value question for you.

If you were to buy a business and you bought it at its intrinsic value, what’s the minimum after-tax free cash flow yield you’d need to get?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, your question is if we were buying all of a business and we’re buying at what we thought was intrinsic value, what was the minimum —

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Correct.

WARREN BUFFETT: — present earning power or what the present — the minimum discount rate of future streams?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: No, what’s the minimum current after-tax free cash flow yield you’d…

WARREN BUFFETT: We could conceivably buy a business — I don’t think we would be likely to — but we could we could conceivably buy a business that had no current after-tax cash flow. But, we would have to think it had a tremendous future.

But we would not find — obviously the current figures, particularly in the kind of businesses we buy, tend to be representative, we think, of what’s going to happen in the future.

But that would not necessarily have to be the case. You can argue, for example, in buying stocks, we bought GEICO at a time when it was losing significant money. We didn’t expect it to continue to lose significant money.

But if we think the present value of the future earning power is attractive enough compared to the purchase price, we would not be overwhelmed by what the first year’s figure would be.

Charlie, you want to add to that?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Yeah. We don’t care what we report in the first year or two of — after buying anything.

AUDIENCE MEMBER OFF MIC: (INAUDIBLE) on average over the years (INAUDIBLE).

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I would say that in a world of 7 percent long-term bond rates that we would certainly want to think we were discounting future after-tax streams of cash at at least a 10 percent rate.

But that will depend on the certainty we feel about the business. The more certain we feel about a business, the closer we are willing to play it.

We have to feel pretty certain about any business before we’re even interested at all. But there are still degrees of certainty, and —

If we thought we were getting a stream of cash over the next 30 years that we felt extremely certain about, we would use a discount rate that would be somewhat less than if it was one where we thought we might get some surprises in five or 10 years — possibility existed. Charlie?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Nothing to add.

14. Insurance business intrinsic value is well above book value

WARREN BUFFETT: OK. Zone 4.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Morris Spence (PH) from Omaha, Nebraska.

You’ve made comments on several occasions about the intrinsic business value of the insurance operations. And in this year’s report you state that the insurance business possesses an intrinsic value that exceeds book value by a large amount, larger, in fact, than is the case at any Berkshire — other Berkshire business.

I was wondering if you would explain in greater detail why you believe that to be true.

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I — it’s very hard to quantify, as we’ve said many times in the report. But, I think that it’s clear that even taking fairly pessimistic assumptions, that the excess of intrinsic value over carrying value is higher, by some margin, for the insurance business.

And I think that the table in the report that shows you what our cost to float has been over the years, and also what the trend of float has been over the years, would, unless you thought that table had no validity for the future, I think that that table would tend to the point you in the direction of saying the insurance business does have a very significant excess of intrinsic value over carrying value.

Very hard number to put something on. But — and you don’t want to extrapolate that table out. But I think that table shows that we started with maybe 20 million of float and that we’re up to something close to three billion of float. And that that float has come to us at a cost that’s extremely attractive, on average, over the years.

And just to pick an example, last year, when we actually had an underwriting profit, the value of that float was something over $200 million. And that figure was a lot bigger than it was 10 years ago or 20 years ago.

So that’s — that is a stream — last year was unusually favorable, but that is a — that’s a very significant stream of earnings, and it’s one we feel we have reasonably good prospects in. So we feel very good about the insurance business.

15. Why Berkshire doesn’t split its stock

WARREN BUFFETT: OK. Zone 5?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: My name is Cy Rademacher (PH) from Omaha.

Is there any point at which your stock would rise to the point where you might split the stock?

WARREN BUFFETT: Surprise, surprise. (Laughter)

I think I’ll let Charlie answer that this year. (Laughs)

He’s so popular with the shareholders that I can afford to let him take the tough questions. (Laughter)

CHARLIE MUNGER: I think the answer is no. (Laughter and applause)

I think the idea of carving ownerships in an enterprise into little, tiny $20 pieces is almost insane. And it’s quite inefficient to service a $20 account and I don’t see why there shouldn’t be a minimum as a condition of joining some enterprise. Certainly we’d all feel that way if we were organizing a private enterprise.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, we would not carve it up in $20 units.

We find it very — it’s interesting because every company finds a way to fill up its common shareholder list. And you can start with the As and work through to the Zs and you’ll — every company in the New York Stock Exchange, one way or another, has attracted some constituency of shareholders.

And frankly, we can’t imagine a better constituency than is in this room. I mean, we have — we don’t think we can improve on this group, and we followed certain policies that we think attracted certain types of shareholders and actually pushed away others.

And that is part of our eugenics program here at Berkshire. (Laughter)

CHARLIE MUNGER: Yeah, just look around this room and as you mingle with one another. This is a very outstanding group of people. And why would anybody want a different kind of a group?

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, if we cause — if we follow some policies that cause a whole bunch of people to buy Berkshire for the wrong reason, the only way they can buy it is to replace somebody in this room, or in this larger metaphorical room, of shareholders that we have.

So someone in one of these seats gets up and somebody else walks in. The question is do we have a better audience?

I don’t think so. So I think that — I think Charlie said it very well.

16. Buffett is keeping his private jet

WARREN BUFFETT: Zone 6.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Mr. Buffett, my name is Rob Na (PH) and I’m from Omaha, Nebraska.

My question is, given the recent announcement of Midwest Express and their nonstop jet service between East and West Coasts, will this cut down on your use of “The Indefensible?” (Laughter)

And will you use more commercial air travel?

WARREN BUFFETT: This is a question planted by Charlie. (Laughter)

I think you should know, I take it to the drugstore at the moment, and I — (Laughter)

No, it’s just a question when I start sleeping in it at the hangar.

Nothing will cut back on “The Indefensible.” It’s being painted right now, but I told them to make it last a long time.

Charlie, though, was pointing out the merits of other kinds of transportation last night at the meeting of our managers. He might want to repeat those here.

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, I just pointed out that the back of the plane arrived at the same time as the front of the plane, invariably. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: He’s even more of an authority on buses, incidentally, if anybody has his — (Laughter)

17. Buffett’s next goal in life

WARREN BUFFETT: Zone 7.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Mr. Buffett, my name’s Allan Maxwell from Omaha. I’ve got two questions.

What is your next goal in life now that you’re the richest man in the country?

WARREN BUFFETT: That’s easy. It’s to be the oldest man in the country. (Laughter and applause)

18. “Two yardsticks” for judging management

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Secondly, you talk about good management with corporations and that you try and buy companies with good management.

I feel that I have about as much chance of meeting good managers, other than yourself, as I do bringing Richard Nixon back to life.

How do I, as an average investor, find out what good management is?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I think you judge management by two yardsticks.

One is how well they run the business and I think you can learn a lot about that by reading about both what they’ve accomplished and what their competitors have accomplished, and seeing how they have allocated capital over time.

You have to have some understanding of the hand they were dealt when they themselves got a chance to play the hand.

But, if you understand something about the business they’re in — and you can’t understand it in every business, but you can find industries or companies where you can understand it — then you simply want to look at how well they have been doing in playing the hand, essentially, that’s been dealt with them.

And then the second thing you want to figure out is how well that they treat their owners. And I think you can get a handle on that, oftentimes. A lot of times you can’t. I mean it — they’re many companies that obviously fall in — somewhere — in that 20th to 80th percentile and it’s a little hard to pick out where they do fall.

But, I think you can usually figure out — I mean, it’s not hard to figure out that, say, Bill Gates, or Tom Murphy, or Don Keough, or people like that, are really outstanding managers. And it’s not hard to figure out who they’re working for.

And I can give you some cases on the other end of the spectrum, too.

It’s interesting how often the ones that, in my view, are the poor managers also turn out to be the ones that really don’t think that much about the shareholders, too. The two often go hand in hand.

But, I think reading of reports — reading of competitors’ reports — I think you’ll get a fix on that in some cases. You don’t have to — you know, you don’t have to make a hundred correct judgments in this business or 50 correct judgments. You only have to make a few. And that’s all we try to do.

And, generally speaking, the conclusions I’ve come to about managers have really come about the same way you can make yours. I mean they come about by reading reports rather than any intimate personal knowledge or — and knowing them personally at all.

So it — you know, read the proxy statements, see what they think of — see how they treat themselves versus how they treat the shareholders, look at what they have accomplished, considering what the hand was that they were dealt when they took over compared to what is going on in the industry.

And I think you can figure it out sometimes. You don’t have to figure out very often.

Charlie?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Nothing to add.

19. How Berkshire keeps great managers

WARREN BUFFETT: Ok, we’re back to zone 1.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hi there. My name is Lee. I’m from Palo Alto, California.

In meeting Ajit Jain, I’ve been very impressed over the years. And I think I even met his parents once they came from India.

Please comment on your deepest impressions of his personality and managerial skills, and also how you go about exactly keeping somebody who has such fine skills within the fold. He might go to Walt Disney someday and, you know, pull down 200 million.

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, if he gets offered 200 million — (laughs) — we may not compete too vigorously at that level. (Laughter)

We basically try to run a business so that — Charlie and I have two jobs. We have to identify and keep good managers interested after we’ve figured out who they are.

And that often is a little different here, because I would say a majority of our managers are financially independent, so that they don’t go to work because they are worried about putting kids through school or putting food on the table. So they have to have some reason to go to work aside from that.

They have to be treated fairly in terms of compensation, but they also have to figure it is better than playing golf every day or whatever it may be.

And, so that’s one of the jobs we have and we basically attack that the same way — we look at what they do the same way we look at what we do.

We’ve got a wonderful group of shareholders. Before I ran this, I had a partnership. I had a great group of partners. And essentially, I like to be left alone to do what I did. I like to be judged on the scorecard at the end of the year rather than on every stroke, and not second guessed in a way that was inappropriate.

I like to have people who understood the environment in which I was operating.

And so the important thing we do with managers, generally, is to find the .400 hitters and then not tell them how to swing, as I put in the report.

The second thing we do is allocate capital. And aside from that, we play bridge. (Laughter)

Pretty much what happens at Berkshire.

So, with any of the managers you might name here, we try to make it interesting and fun for them to run their business. We try to have a compensation arrangement that’s appropriate for the kind of business they’re in.

We have no company-wide compensation plan. We wouldn’t dream of having some compensation expert or consultant come in and screw it up. (Laughter)

We try to — some businesses require a lot of capital that we’re in, some require no capital. Some are easy businesses where good profit margins are a cinch to come by, but we’re really paying for the extra beyond that. Some are very tough businesses to make money in.

And it would be crazy to have some huge framework that we try to place everybody in that — where one size would fit all.

People, generally, are compensated relating in some manner that relates to how their business does as opposed to — there’s no reason to pay anybody based on how Berkshire does, because no one has responsibility for Berkshire except for Charlie and me.

And we try to make them responsible for their own units, compensated based on how those units do.

We try to understand the businesses they’re in, so we know what the difference between a good performance and a bad performance —

And that’s about — that’s how we work with people.

We’ve had terrific luck over the years in retaining the managers that we wanted to retain. I think, largely, it’s because — particularly if they sell us a business — to a great extent, the next day they’re running it just as they were the day before. And they’re having as much fun running their business as I am running Berkshire.

Charlie?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, I’ve got nothing to add, but I think that concept of treating the other fellow the way you’d like to be treated if the roles were reversed — it’s so simple, when you stop to think about it, but —

It’s a rare evening when Ajit and Warren aren’t talking once on the phone. It’s more than a business relationship, at least it seems that way to me.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, well, it is. It will stay that way, too.

CHARLIE MUNGER: And by the way, we like our businesses — our relationships — to be more than a business relationship

WARREN BUFFETT: Charlie and I are very — we basically — it’s a luxury but it’s a luxury that we should try to nurture — we get to work with people we like. And it makes life a lot simpler.

It probably helps in that goal of being the oldest living American, too. (Laughter)

CHARLIE MUNGER: Yeah, and we tend to like people we admire. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, who do we like that we don’t admire, Charlie? (Laughter)

Start naming names. These people have names. (Laughter)

20. Guinness hurt by weak demand for scotch

WARREN BUFFETT: Zone 2.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: My name is Peter Bevelin from Sweden.

How do you perceive Guinness long-term, economics growth-wise?

WARREN BUFFETT: Fitz — would you repeat that please, Fitz. What was it? What firm growth-wise?

VOICE: Guinness.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Guinness.

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, Guinness.

I’m not as much of an expert on Guinness’ products as Charlie is.

CHARLIE MUNGER: We approved that. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: You didn’t hear him. He said, “I approved that.”

I made the decision to buy Guinness and Guinness has — it’s down somewhat from — actually, the price in pounds is about the same but the pound is at about $1.46 or -7 against an average of $1.80-something, so we’ve had a significant exchange loss on that.

The — Guinness’ — despite the name — you know, the main product, of course, is scotch. And that’s where most of the money is made, although they make good money in brewing.

But, distilling is the main business. And, you know, the usage of scotch, particularly in this country, the trends have not been strong at all, but that was true when we bought it, too.

There are some countries around the world where it’s grown and there are certain countries where it’s a huge prestige item.

I mean, in certain parts of the Far East, the more you pay for scotch, the better you think people think of you. Which I don’t understand completely, but I hope it continues. (Laughter)

But — the scotch — worldwide scotch consumption has not been anything to write home about.

Guinness makes a lot of money in the business. But, I would not — I don’t see anything in the — in published history that would lead you to believe that the growth prospects, in terms of physical volume, are high for scotch.

The — Guinness itself, the beer, actually has shown pretty good growth rates in some countries. Actually, from a very tiny base in the U.S. as well.

But, they will have to do well in distilling or — I mean that will govern the outcome of Guinness.

I think Guinness is well run and it’s a very important company in that business. But, I wouldn’t count on a lot of physical growth.

Charlie, what — any consumer insights?

CHARLIE MUNGER: No. (Laughter)

21. Why Berkshire will be OK if Buffett dies suddenly

WARREN BUFFETT: Zone 3.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Mr. Buffett, my name is Arthur Coleus (PH) from Canton, Massachusetts.

And I’d like to know how you’d respond to the question that my associates ask me when they say that Berkshire Hathaway has been a good investment up to now, but what happens to your investment if, God forbid, something happens to Mr. Warren Buffett?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I’m glad you didn’t say Charlie Munger. (Laughter)

No, there — Berkshire will do just fine. We’ve got a wonderful group of businesses.

I’ve told you the two things I do in life. And, in terms of the managers we have, you have to come in and really want to mess it up, I would think. And we don’t have anybody like that, in terms of succession plans at Berkshire.

And then there’s the question of allocation of capital. And, you could do worse than just adding it to some of the positions that we already had.

The ownership is — if I die tonight, the ownership structure does not change. So, you’ve the same large block of stock that has every interest in having good successor management as I would.

I mean, there’s no — there would be no greater interest. And it is not a complicated business. I mean, you ought to worry more about, if you own Microsoft, about Bill Gates, I think, or something of the sort.

But, this place is, you know, we’ve got a group down here that are running these. You didn’t see me out at Borsheims selling any jewelry the other day. I mean, that’s somebody else’s job. So, I — it is not — it’s not very complicated.

Incidentally, I think I’m in pretty good health. I mean this stuff (Coca-Cola) will do wonders for you if you’ll just try it. (Laughter)

Charlie, do you want to add anything as the —?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Yeah. I think the prospects of Berkshire would be diminished — obviously diminished — if Warren were to drop off tomorrow morning. But it would still be one hell of a company and I think it would still do quite well.

I used to do legal work, when I was young, for Charlie Skouras. I heard him once say, my business, which was movie theaters like this one, was off 25 percent last year, and last year was off 25 percent from the year before, and that was off 25 percent from the year before, and then he pounded the table and he’d say, “But it’s still one hell of a business.”

WARREN BUFFETT: It’s not a formula we want to test, incidentally.

CHARLIE MUNGER: No, no. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: It is one hell of a business that we’ve got here. I mean — and if you saw what happened at Berkshire headquarters, you would not worry as much. There’s very little going on there that contributes to things. (Laughter)

We’re, right now, at our peak of activity. This is it.

22. Easy answer: no reverse split, either

WARREN BUFFETT: Zone 4.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: First of all, my name is Al Martin (PH) and my wife Terry (PH) is here with me. And I appreciate the invitation to attend this meeting.

I was a little bit dubious and quite excited at that game Saturday night. I didn’t know which side was going to throw the game to the other one. But I did find out at the end.

The first question, actually, was somewhat answered, but not fully. Has the board considered a reverse split? My experience has been that —

WARREN BUFFETT: Would you like to make that a motion? There was a motion for a reserve — reverse split. (Laughter)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I would say a two-for-one because if it were three or four-for-one I might end up with no shares. Or fractional shares.

But, anyway, my experience has been that all of the stocks that have split have gone down in the next two or three months or the next two or three years, including one which you are drinking, which is a flat Coke.

Also, I have observed Merck over the last several years to be hitting a low, which split three-for-one.

So, I think that, you know, the reasons for splitting stocks are to make it affordable. I found that every stock I ever bought was never affordable. I found the reason I bought it was because I couldn’t afford not to buy it.

So that’s a different philosophy, I guess, as somewhat shared indirectly with the boards running the stock.

The second question, which is — has to do with —

WARREN BUFFETT: Hope it’s as easy as the first question. (Laughter)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Well, I didn’t want to wait for an answer of the first question for that reason, because it could be complicated and confusing and so forth.

23. Hillary Clinton’s success as commodities trader

AUDIENCE MEMBER: The second question has to do with, could the board consider looking into a commodity broker, or a lawyer, or both, that could take action similar to Hillary Clinton’s?

I think, you know, making your net worth go up by a factor of five overnight is more than enticing. Some of us might even want to wait for ten months to get a 100-to-1 return on the money.

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I want to say — I want to say to you, when I saw that 530 percent in one day, it — Charlie has never done that for us.

I mean — (laughter) — it really caused me to reassess succession plans at Berkshire. (Laughter)

And Hillary may be free in a few years. (Laughter and applause)

I hope you’re applauding over her coming to Berkshire, not — but I’ll leave that up — (Laughter)

OK, that was their second question. (Laughs)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: That was my second question.

Of course, in my experience, it’s been that most of us have thought through this situation and I guess it’s pretty speculative, but I found out that the rules and laws that are made for trading are interpreted rather than enforced. And I think that applied to this particular case, so let’s go on to the third question. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: Alright. They’re getting easier. (Laughter)

24. Blue Chip Stamps is a disaster under Buffett and Munger

AUDIENCE MEMBER: This one is real easy. My wife was a collector of Blue Chip stamps for many, many years. And she brought some stamps with her. What should she do with them?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, that — we can give you a definitive answer to that. Charlie and I entered the trading stamp business to apply our wizardry to it in what, 1969 or so, Charlie?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Yes.

WARREN BUFFETT: We were doing what then, about 110 million?

CHARLIE MUNGER: No, it went up to 120.

WARREN BUFFETT: OK. And then we arrived on the scene and we’re going to do what, about 400,000 this year?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Yes.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah. (Laughter)

That shows you what can be done when your management gets active. (Laughter)

CHARLIE MUNGER: We have presided over a decline of 99 1/2 percent. (Laughter)

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah. Yeah. But, we’re waiting for a bounce — (Laughter)

I would say this. The trading stamp business, as those of you who have followed all know, it only works because of the float.

I mean, there — a very, very high percentage of the stamps in the ’60s were cashed in. We have some years that we’ve gone up to 99 percent, I believe — we sampled the returns — because they were given out in such quantity.

But, our advice to anyone who has stamps is to save them because they’re going to be collector’s items, and besides if you bring them to us we have to give you merchandise for them.

Tell her to keep them. They’ll do nothing but gain in value over years. (Laughter)

25. Stock split wouldn’t raise long-term average price

WARREN BUFFETT: Going back, incidentally, to your point on the split.

I think most people think that the stock would sell for more money split.

A, we wouldn’t necessarily think that was advisable in the first place.

But we — in the second place, we don’t think it would necessarily be true over a period of time.

We think our stock is more likely to be rationally priced over time following the present policies than if we were to split it in some major way.

And we don’t think the average price would necessarily be higher. We think that the volatility would probably be somewhat greater, and we see no way that volatility helps our shareholders as a group.

26. Fed Chairman Greenspan’s actions are “quite sound”

WARREN BUFFETT: Zone 5.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I am Peg Gallagher from Omaha.

Mr. Buffett, are you interested in influencing Mr. Greenspan at the Fed to stop raising interest rates?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I wouldn’t have any influence with him. He was on the board of Cap Cities some years ago and I know him a bit. But I don’t think anyone would have any influence with Mr. Greenspan on that point.

But, I generally think that his actions have been quite sound during his period as Fed chief.

I mean, it’s part of the job of the Fed, as Mr. Martin said many years ago, was to take away the punchbowl at the party, occasionally. And that’s a very difficult, difficult policy to quantify working with markets day-by-day.

And, of course, it’s always been the job of the Fed, basically, to lean against the wind. Which, of course, means if the wind changes, you fall flat on your face. But that’s another question.

But the — I don’t — I think what he has done is probably been somewhat appropriate. I think he’s probably been surprised, a little bit, as to what has happened with long-term rates as he’s nudged up short-term rates.