#to see if there were anymore paintings that reminded me of the kris photos

Text

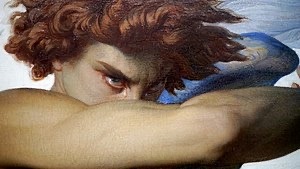

kris guštin // danaë gustav klimt // the fallen angel aexandre cabanel // bojan cvjetićanin

#kris guštin#bojan cvjetićanin#joker out#damon baker#i feel so obnoxious for this. sorry#unironically pulled out my 5 kilo gustav klimt artbook and looked through it today#to see if there were anymore paintings that reminded me of the kris photos#there was like one but that was a stretch so#also i was fighting for my life trying to figure out how to credit the photos like. can someone PLEASE just post them#edit: IDK if the the links arent working. whatever. who care

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

late late werewolf

I chewed on @wickershire‘s ask for a werewolf carpool karaoke timestamp for weeks, and then tumblr fuckin’ ate it, but here’s the outcome anyway. It’s mostly inspired by this photo and this video, and also here’s some Azoff den house porn and Jamesy baby’s place in Malibu.

--

Los Angeles is thicker with wolves than London is. James hadn’t realized that when he made the move. He’d only known that the boys were in and out of LA as much as London anymore, and hoped that would be enough to keep him from getting lonely. So it was a surprise to discover that LA has a disproportionately influential network of werewolves, and a bigger surprise to find himself welcomed into it.

James isn’t easily dazzled by superstars. It’s hard to be, when you’ve hoovered One Direction’s fur off your sofa. But he still can’t quite believe that he and Justin Timberlake get together every couple of months to chase coyotes in Griffith Park.

All the same, there’s nothing like seeing the boys. Any of them. So he’s only half-joking when Harry mentions doing the show during album promo, and James suggests that he stay for a week. move into the studio, you can sleep under my desk, he texts.

i’ll wee on your rug, comes the response. They trade increasingly terrible jokes about overnight guests and Harry earning his keep, and then James heads into a meeting and puts it out of his mind. He won’t need to remind Ben to get Harry scheduled as a musical guest when the time comes. Maybe they can even get a skit out of him.

The next day, Jeff Azoff calls. “Harry said he’s been talking to you about doing a week on the show?”

It takes James a moment to remember the text chain from the day before. Following through on vague ideas about getting together isn’t usually Harry’s thing. Their friendship is more of an endless series of joking texts and unfulfilled promises to make plans, right up until the point when Harry needs a sympathetic ear and someone to scratch his. That’s when he turns upon James’s doorstep.

He’s not sure whether Jeff’s interested in the idea, or calling to chew him out about presuming there’s a place for the Late Late Show in Harry’s well-oiled highly calculated promo plans. “Yeah,” James says, hoping for the best. “Yeah, we’d mentioned that.”

“Harry likes the idea,” Jeff says. “We all do. Let’s get it scheduled.”

Jeff starts talking about timing and strategy, moving other commitments to free up a whole week, and James checks out. Ben can handle that part. Ben’s not a wolf, and therefore Ben can have pleasant uncomplicated professional interactions with Jeff. Every conversation that James has with Jeff is shaped by crosscurrents of hierarchy and power that flow well beyond the two of them. Especially when the conversation’s about Harry.

James wants to believe that this residency is Harry following through, for once. This is Harry wanting to have some fun together. But he can’t help the uncomfortable suspicion that Jeff’s driving this somehow, and, inevitably, behind Jeff is his father.

Irving Azoff is the most powerful alpha in Los Angeles, and James doesn’t want to owe him any favors.

***

Late one night the week before the show, James’s phone rings with What Makes You Beautiful, and Harry’s photo pops up. James still uses an old picture from London, Harry wrapped up in a blanket burrito on James’s couch, managing to look disgruntled even as he naps. It’s a surprise; he hadn’t expected to hear from Harry until rehearsal later in the week. James swipes to answer the call, wondering what’s going on. “Harold!”

“Hellooooo,” Harry croons.

James remembers all over again how a direct hit of Harry’s voice is both soothing and disorienting. “You in town?”

“Not yet, flying tomorrow.” That explains the late phone call; Harry’s just waking up bright and early in London.

“Looking forward to next week,” James says, flipping the lock on the sliding door and starting up the stairs toward his bedroom.

“Sure, it’ll be fun.”

“Rehearsal Wednesday, right?”

“Yeah, Wednesday.” Harry pauses.

James waits him out for a moment before reaching for a prompt. “Where are you staying?” James realizes he hadn’t even offered, although Harry ought to know he’s always welcome.

“My place is going on the market.” James had forgotten Harry even had a house in LA. He still seems to prefer staying with somebody else when he’s in town, Ben and Meri or Jeff and Glynne or Cindy and Rande. Sometimes James, but James had assumed that moving out to Malibu last year would take him out of the rotation.

Harry’s still talking, rambling around to some kind of a point. “The art’s going into storage, and they’re going to like, fill in the nail holes, or paint or something, or maybe it’s something happening to the floors, I don’t remember. I think they took the rugs out too. So I’m staying with Jeff, but on Thursday we’ll all be up at his family place for the full moon, and do you want to come with?”

A loaded invitation. “Are you sure that’s all right?”

“Sure,” Harry says, broadly. “Irv actually said I should invite you.”

Which doesn’t do anything to allay James’s trepidation. But he’s not going to pass up a rare full moon with Harry, even if the rest of the company’s not ideal. “All right,” James says, like it’s easy as can be. “Tell Irving thanks for the invite.”

James wonders uncomfortably if Harry would still be going up to the Azoffs if Louis and Niall were in town. There’s no point asking him, though. In addition to it being an entirely academic question, James knows he’d only get a vague nonanswer about how Harry loves the pack and would never regret being part of it. He hasn’t left, not officially. Not like Zayn did, bloody and unmistakeable, the other four smelling of scorch and fever as they tried to rebuild the pack’s toppled scaffolding.

James doesn’t wish that on Louis again. But at least it was definitive. Not like the vague drift away that James worries Harry’s trying to accomplish, or Liam’s taciturn withdrawal into domesticity. Niall’s the only one left to bear the fierce weight of Louis’s love.

***

They film a sketch on the day before the full moon. Afterwards, Harry rides with James from the studio up to Holmby Hills. The ornate streetlights are just coming on, and the sharp scent of the towering box hedges is shot through with the fragrance of spring jasmine. The gate at the Azoffs’ opens when they pull up to it, which only serves to make James wonder how his Range Rover’s been recognized. Harry points him toward an appropriately deferential parking spot in the tree-lined circle drive.

There’s a wolf curled up in the middle of the terraced walkway to the house, sharp eyes watching them as they approach. “Chelsea!” Harry calls, and bends down to give her a vigorous backscratch. She snorts and headbutts him. James refrains, assuming he’d get a sharper reaction if he tried scratching Chelsea Handler’s back.

The front door’s standing open, and Shelli Azoff glides down the wide entrance hall to greet them as they approach. “Harry!” She kisses him on each cheek, Harry preening at the motherly attention. “Jeff and Glynne are out back.”

Harry tips a salute to James and saunters off down the high-ceilinged hallway toward the dining room. Shelli turns to James. “So glad you could join us tonight.”

“It’s my pleasure,” James says. Without Harry, he feels a bit like he’s been thrown to the wolves, literally. “Thank you for having me.”

Shelli tucks her arm through his and steers him deeper into the house. “Let’s get you a drink.”

The sprawling villa is made for a pack, with wide-open passages that won’t spook a wolf and French doors open to the exterior in every room. As they pass through an internal courtyard, a black-clad server appears at Shelli’s elbow and a gin and tonic smoothly makes its way into James’s hand.

The Azoff pack is large, and James recognizes most of the faces circulating through the house and down the terrace around the pool. It’s an even mix of artists -- the big names Irving’s represented over the years -- and others from the business side. James realizes that unless the Gerber kids are running around somewhere, Harry’s the youngest one here by close to a decade. No wonder Harry’s comfortable with the Azoff crowd, James reflects. He’s always happy when he’s surrounded by people competing to parent him.

Kris Jenner joins James and Shelli on the terrace. As the women greet each other, James looks past them to an elaborate spread of capaccio arranged on carved ice blocks. The small square plates and tray of cornichons and mustard suggest it’s offered for humans, but the sheer volume of raw meat means wolves will be finishing it off later.

To James’s relief, Kris stays to talk to him after Shelli melts away to ensnare someone else. It’s no trick to sustain a conversation with Kris. The only tricky part is to extract yourself before you hear more than you ever wanted to.

“Kim and Kendall here tonight?” he asks. They’re the only wolves among Kris’s brood. It’s never certain that the gene will pass down, when only one parent’s a wolf. James admires that Kris doesn’t seem to let it bother her. He’s never seen her show any favoritism between her daughters who are pack and the others who aren’t.

“No, Kendall’s with her friends,” Kris says, gesturing into the distance with her glass of white wine. “Kim and Kanye mostly do their own thing.”

Kanye West, all the cunning and power of an alpha but too volatile to convince anyone to follow him. Marrying into the Azoff pack didn’t help matters; of all the rumblings James has heard around who might succeed Irving someday, Kanye’s name is never in the mix. He asks Kris about her grandchildren instead, filling up the space until Irving Azoff steps out of a French door behind James and straight into their conversation.

“James! Glad you could make it.” Irving gives him an LA handshake and James feels disoriented by the disconnect between his appearance and his scent. A short man with an unapologetically receding hairline, Irving looks like the odd one out at this cocktail party full of famous artists and the expensively maintained team behind them. Breathe in, though, and his scent says not just that Irving’s willing to break a few eggs to make an omelet, but that he’s about to upend the entire henhouse and feast on the chickens.

“Wouldn’t miss it,” James says. “You’ve got a lovely property here.”

Irving scoffs. “Temporary. Thought we’d be back in our place by the end of last year. Architect’s fucking incompetent.” He rants to James about the renovation gone wrong on his Beverly Hills mansion, and James relaxes into the conversational safe harbor.

When he steps to the side to set his glass down on a patio table, it’s almost immediately whisked away by an efficient server with a low ponytail and a tray of empties. She glides silently toward the kitchen, and doesn’t even flinch when Chelsea brushes past her, tail catching on the edge of the tray.

James wonders how Irving and Shelli find staff they can trust, what it must cost them. James is careful to schedule his own house manager for a day off the morning after a full moon, and wipe up any pawprints himself so his cleaners have no reason to ask questions. His chef only knows that James likes a high-protein diet and steak cooked rare.

He snaps back to attention when he hears Harry’s name. “Glad to hear he’s doing a week with you,” Irving says.

“Well, we’re happy to have him.” James concentrates on breathing steady and slow, willing his scent not to give off any trace of nerves.

“You’ve always been a good friend to Harry.” Irving shifts his highball glass from one hand to the other. “He looks up to you.”

“That’s hard to believe,” James says. Hard to remember Harry as a sixteen-year-old kid who needed anything from James. Somewhere along the way, the whole world started giving Harry whatever he needs, abundantly and enthusiastically.

“He’s doing well,” Irving agrees, as if he’s thinking the same thing. James tries to stifle a flare of irrational possessiveness. He doesn’t need Irving to tell him how Harry’s doing.

Maybe something comes through in his scent, because Irving changes the subject. “You have a pack in LA?”

“No,” James answers quickly, reaching for the lighthearted emigre persona he relies on to dodge whatever ulterior motive is behind questions like this. “Still holding onto that last tie to Buckinghamshire.”

Irving doesn’t oblige him with a laugh or a joke about how you can’t go home again or a comment about the superiority of Los Angeles weather. He just looks at James, silently, and even though James knows it’s meant to unnerve him, it works anyway.

“Door’s always open here,” Irving says, after a pause.

“Thanks,” James says, shoulders down and chin tipped forward just a little, deferential. “I appreciate that.”

“We’d like to consolidate Harry’s supporters.” James didn’t see Irving move, but all of a sudden he seems uncomfortably close. “The next few months are going to be critical. It’ll help to have a good pack behind him.”

James has to stop himself from baring his teeth. Harry has a pack, and it’s not this one. Or maybe there’s something Harry hasn’t told him, or something on the horizon. Irving has a way of making the world conform to his vision.

The moon’s not up yet, but James’s body aches to shift. “Thanks,” he says, again. “I’ll keep it in mind.”

“You do that.” Irving tips his glass at someone over James’s shoulder. As he starts to move in that direction, he looks back at James. “LA’s a tough place to be a lone wolf.”

James goes in search of another drink, feeling that he’s more than earned it. While he waits for the bartender to mix him a double, he notices a handful of party guests slipping down a hall that leads away from the central part of the villa. A few minutes later, they reemerge as wolves, padding through the lounge and out the broad sliding doors to the terrace.

Shifting seems like an even better idea than more gin. James explores the hallway and finds a series of spare bedrooms. Each has an assortment of clothing neatly folded on the bed or hanging in the closet, ready for the owners to reclaim when they shift back. How civilized, James thinks. He undresses and leaves his shirt and trousers in a tidy pile on the bed, thinking nostalgically about the boys’ hoodies and high-tops scattered all over his garden back in London. Even with moonrise not quite here, the shift comes easily, as if his body understands that it’s much less complicated to be a wolf than a human in this place.

James slips out the bedroom’s French doors to the side of the house and circles back around to the yard. He emerges just in time to see Harry tossing his skinny jeans and flowered shirt on a lounge by the pool and shifting in full view of the remaining humans. Either Harry hasn’t bothered to pay attention to the pack’s customs, or he’s just well aware that nobody at this party’s going to mind an eyeful of his lean body and lesser-seen tattoos.

To the surprise of absolutely no one, Harry’s grown up into a striking wolf. His chest and shoulders have finally caught up with his long limbs and outsized paws, and his puppy fluff has resolved itself into a sleek dark coat. James bounds toward him and Harry yaps and darts off to the edge of the property, waiting for James to follow. They run through the trees and down an empty lot, emerging onto a golf course dotted with wolves. James has heard it before, but never quite believed it: Holmby Hills has enough wolves that they can afford to be a bit brazen about it on a full moon night.

The rolling fairways and the even scent of mown grass are a different experience than the Santa Monica Mountains, where James usually spends his shifts. He runs full tilt down the well-manicured course, overtaking Harry, who stays on his heels as they leave the coalescing pack behind. They weave through scattered stands of trees and leap across flat teeing grounds. James finally pulls up short and tackles Harry into a bunker. They roll over and over together in the sand like a pair of idiots, like six years never went by at all.

***

James leaves Harry at the Azoffs the next morning, heading home in the early dawn hours for a shower and a few hours of sleep. He sees him again at the studio that day, and all the next week, but there’s no chance to really talk there, surrounded by PAs and camera crew and Jeff ever-present in the background. Harry’s residency ends all too quickly, with a transcendent spark-shooting finale that has James half wondering the next morning if he dreamed the entire week.

Then, Harry’s gone. They see each other briefly in London a few weeks later, but it’s more of the same, always surrounded by the band, the crew, a theater full of people. Seeing Harry in person isn’t much different than their text message chain: sporadic outbursts of jokes that make only the two of them laugh, interspersed by long periods of nothing.

After the London show, James doesn’t hear from Harry again until his phone rings at the end of July, right as Dunkirk promo is winding down.

“I’m coming to LA for a bit before tour starts,” Harry says. “Could I stay at yours for a few days?”

“’Course you can, you know you’re always welcome.” As if James would ever tell him no. “You sure you want to be out in Malibu?”

“Yes,” Harry says, with certainty. “Want to get away a little, you know? Sit by the sea, nobody bothering me.”

He arrives at nearly midnight, the lingering traces of London in his scent almost overpowered by the stale coffee smell of air travel. James makes him a mug of tea and – when he almost falls asleep with his face in it – points him toward a guest bedroom.

Upstairs in his own room, James considers for a moment and then leaves the bedroom door slightly ajar. He doesn’t exactly expect Harry to come bounding up onto his bed like old times, but he’s not going to rule it out.

Then, instead of the clicking toenails of a wolf nosing its way through the cracked door, James hears soft knocking against the frame. Just a couple of quick and tentative raps, only loud enough for wolf ears.

“Harry?” James calls from bed. “It’s open.”

There’s just enough light to see that Harry’s shirtless and barefoot, in joggers. The black blotches of his tattoos look like absences in the dark room, like something’s chewed holes in him.

He gestures at the far side of James’s bed. “All right?”

“Sure, yeah,” James says, tugging the covers back for him. Harry takes up less space as a human, but he still radiates warmth as he settles in, turning himself over and back again, the human echo of his wolf tromping a circle into the duvet. He squirms his head down into his pillow, and then scoots closer to push his forehead into the side of James’s shoulder.

James freezes. He doesn’t know what to do with the gesture, somewhere halfway between human and wolf. After a moment he responds in kind, reaching his other hand over to scratch Harry’s head. Harry hums as if he’s pleased.

He’s silent for a few minutes after James finishes a lengthy head-scratch, but his breathing doesn’t slow into sleep. Finally, quietly, he asks, “How are they?”

“You’re not in touch?” James tries not to sound surprised or concerned.

Harry’s voice is half muffled by the pillow and the top of James’s arm. “There’s emails or texts or whatever, but.”

James understands. It’s easy to hide in plain sight in a text message chain. No way for the others to scent the truth, the way you can when your pack is nearby. “They’re good,” he says. “Truly, good. Niall’s coming into his own.”

“Louis?”

“Fatherhood suits him,” James says. “You know Freddie’s a wolf, do you?” Louis hadn’t told James, just brought tiny newborn Freddie over for a visit and let James sniff it out for himself. He’d never seen Louis so proud or so happy.

“Yeah.” James can feel Harry smile against his arm.

“And you’ll have Liam’s boy in the pack as well,” James adds. He knows that much, at least; there’s no doubt with two wolves for parents.

Harry’s quiet. After a moment, James says, softly, “They miss you.”

“Do they?” The question’s more skeptical than hopeful.

“Of course they do.” James has to ask, and there won’t be any better time than right now, with Harry in his bed seeking comfort or reassurance or something James hasn’t figured out yet. “Do you miss them?”

Harry makes an ambivalent kind of a noise. “Yes,” he answers hesitantly, drawing out the word. “I miss them. But I can’t have them around and do what I want to do right now.”

James knows. It’s hard to believe he ever advised the boys to tone it down in public, when flaunting their pack bond turned out to be integral to their success. Of course, now that makes it all the harder for Harry to establish himself as anything other than part of the pack. James aches in sympathy, knowing what it’s like to put pack at a remove to accomplish one’s own goals. It’s been so long since he’s felt that way, though. For years he’s had the boys, and now all the other wolves he’s connected with in LA.

“Would you ever…” – James can’t even bring himself to actually say it – “…the Azoffs?”

“No,” Harry says, emphatically. “I don’t miss a pack. I miss my pack.”

“I didn’t know.” James realizes for the first time how much the possibility had worried him. “Irving tried to recruit me. Gave me some line about supporting you.

Harry blows out a frustrated breath, hot against James’s arm. “You aren’t going to, are you?”

“No.” James relaxes down to his toes with the relief of not having to consider it anymore. “I mean, it’s not appealing. But if you did… I’d think about it, I guess.”

“Whatever line he fed you is bullshit,” Harry says. “He wants you as bait. Thinks if you pack up, I will too.”

“How flattering.” Not liking that line of thought, James changes the subject. “You don’t shift at night anymore?”

“Doesn’t feel right, on my own.” Of course, James thinks. Loneliness is easier as a human, with any number of distractions that aren’t available in a wolf’s body.

“Have you shifted since the last full moon?”

Harry thinks for a moment. “Maybe not.”

“Go to sleep,” James says, scratching his head one more time. “We’ll go out early in the morning, run a little ways down the beach.”

“All right.” Harry yawns into the words. He stretches away from James and swings his legs out of bed. James sees a flash of pale skin as Harry sheds his joggers, and then jumps back onto the bed as a wolf. He’s asleep a moment later, sprawled halfway across James’s chest.

#unbeta'd#so concrit willingly accepted before i upload to ao3#turns out i could write in this verse forever#i had to make myself hard stop at 4K#you should see the stuff i cut out#fic#werewolf carpool karaoke#late late werewolf

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cave City

By Jess Awh

On Christmas Day in 2003 I flew into a fit of rage, over what I can’t remember, and cut a sizeable chunk out of the goose. My older brother quickly alerted my mother to the fact I was wielding scissors, which I’d scaled the kitchen counter to obtain, and she wrenched them from my hand with frightful anger in her eyes before whisking the goose away, cradled in her arms, to be patched. They were Madonna and child: she was aflame, tawny blonde hair flying out of her ponytail. The goose stared at me from its haven with little button eyes that loomed out of its sleek green velvet head like individual living creatures.

It had been a preemptive strike. I had to bring that goose to its knees before it had the chance to cut my loved ones down. The goose was retired the next Christmas after a clandestine incident of strangling left its curved neck hanging limp, empty of stuffing.

Ten years later I was fifteen, and for my grandparents’ 50th anniversary I broke out my mother’s sewing kit. The goose had come to me on the previous Thanksgiving, much to my chagrin. It must’ve been with my cousin Steve before then because after everyone had left, I went to vacuum behind the couch he’d been sleeping on and there it was: wedged next to the wall, staring with its one remaining lifeless beetle eye and waving with its one remaining white embroidered wing. Fuck you, Steve, I muttered as I wrenched it free. I set it on the living room floor and slumped onto the couch, at which point we just sort of looked at each other for a minute as if neither of us knew what to do or say. According to tradition, I’d have to find a way to covertly dump the goose on somebody else without them noticing at the next family gathering. Until then, we’d be in each other’s way.

However, seeing as I had dedicated my life to the destruction of stasis in the moment I first removed a chunk from the goose, I shouldered a pair of scissors once again (plus a needle and thread) to realign its neck, replace its eye, and adorn it with pearls and a miniature wedding veil. When we presented it to my grandmother (the one who originally sewed the goose) at the anniversary party, she nearly cried. I was prepared to feel a twinge of affection for it on that day, like a thumbtack in the bottom of my heart, but it never came.

When I was two or three I was able to ride the goose’s back like a rocking horse. At that time it had a red and green ribbon around its neck (the Christmas goose). There are four important landmarks on the leg of I-65 that stretches north from Nashville.

A blackened barn in a barren field that reads, in large crudely painted white letters, “NICEST BATHROOMS ON I-65 NEXT EXIT.” I have never seen the bathrooms because they’re south of Bowling Green and because the barn exudes a concerning energy which almost seems to lock my hand in place if I try to turn the wheel and get on that ramp.

A larger-than-life statue of a milking cow in a flatbed truck parked (precariously) on an overlook west of the highway.

Cave City.

An old red brick farmhouse with a high-ceilinged front porch. Its only neighbor is one tree that’s been blackened and stripped by lightning. My grandmother calls those “bone trees.” Driving from Nashville to Louisville with my third boyfriend, I used to point out that house every time we passed and say “I like that house,” and then I’d say “bone tree,” which is how it quietly became a landmark.

The goose is not good company, but silent company, at least. I like that no one’s asking me where we’re going or why as I careen down I-65 at an alarming speed. I’m driving to Cave City the way a blind man walks from his bedroom to his kitchen— my hands know the route better than my mind does. If I thought about my whereabouts too hard I’d probably have to open a map. It’s like having a dead body in the truck, I think, glancing over at the goose. Not as if I’m a murderer, though; as if I’m used to driving a hearse after a decades-long career of doing so and I sit in comfortable silence with the body, imagining a mild camaraderie, imagining that our quality time will open the buds of kinship one by one into blossoms that adorn our bodies. I’ve only been in a funeral procession once, in Louisville. On that day I learned that cars don’t pull over for funeral processions in every city the way they do in the South, and thus, sometimes part of the ceremony is waiting in traffic. On that day I stopped in Cave City twice. Driving today, I am glad to have the goose in the truck with me rather than a flock of my third boyfriend’s aunts mourning the death of their mother.

I’m driving to Cave City for a different reason than usual. Typically, one stops in Cave City because it’s north of Bowling Green and south of E-town. E-town is a crooked place. A haven only for darkness and pirate-like individuals. Its aura is different from NICEST BATHROOMS, however—different enough that I sometimes find myself stopping there. In late summer the year I turned eighteen I hitched a ride from Albany, Wisconsin back down to Tennessee in a little red car with a man named Joseph Allred. That was one of the times I ended up in E-town. We stopped for gas around nine p.m., and he walked out of the Circle K as I was sitting on the hood of the car smoking a cigarette, hiding from the deep water blue of the nighttime around us in the lemon glow of a streetlamp. He said “it’s been a long time since an angsty teenage girl last sat on the hood of my car smoking a cigarette,” which was a longer sentence than he’d said to me in the entire day of driving. Then he handed me the body of a black swallowtail butterfly we had found fluttering by the pump.

Circle K is one of those places where you can almost touch someone, or you can glimpse what it might feel like to touch that person, but only for the brief interval of a lightning strike.

In childhood I was plagued by an unintentional vagrant’s longing for completeness. My mother often tells the story of the day I found out my heart wasn’t situated in the middle of my chest, behind the soft spot that lies where my lowermost ribs might’ve intersected. I cried and cried—I was inconsolable. For six years after that, I diligently forgot the existence of my body. Then, one day, a handshake from a boy who was elected along with me to fifth grade student council returned me to my form and brought back all of the imperfection.

Driving to Cave City now I am listening to a radio program in which the host asks each of his callers: “what is the most romantic thing that ever happened to you?” One lady says her boyfriend drove from Chicago to New York City to surprise her on Valentine’s day and picked her up at Port Authority in the middle of the night. Somebody says their wife surprised them with a moonlit picnic on the riverbank where they got engaged. One night when I was fifteen, I was standing with my first boyfriend on the bridge over Graffiti Creek down the road from a house party our friend Gustavo was throwing when my ring fell off my finger and dropped in the water. I exclaimed in dismay, but soon after tried to convince him it was no big deal—he jumped in regardless, soaking his sneakers and trouser legs to retrieve what, in the end, had been a green aluminum band from the 25 cent prize machine at the laser tag arcade downtown. The bruise-like stain it left on my finger was as sweet a reminder as the warmth in the memory of his lips on mine that night. I think of calling the radio station to say this as I drive past the statue of the milking cow, but I can’t figure out a way to distill the story into one sentence. I decide it’ll be better off living and dying in the privacy of my own head.

Dave Blaskey. People used to tell me he looked like a basset hound. I was hit with a swing one night that year when we were all getting drunk at the Dragon Park playground—blood blossomed out of my forehead like a red ribbon unfolding, right from the center. There’s a photo of it somewhere. We broke up the next day and it was the only time I’ve ever been dumped. I was too embarrassed to ask why, so I pretended to be unfazed, but I spent the next month canceling plans to sit around at home with a band-aid on my face listening to Chet Baker Sings and throwing little rocks at a picture of Kris Kristofferson taped to my wall. I’m so glad I am not like that now. My heart has never been broken again. There are a few other places like Cave City; I have them marked out in my brain like a little map.

Horseheads. It’s somewhere between New York City and Rochester. The only things in that town are a motel that looks straight out of Lolita, an abandoned strip mall with no signage, and a gas station with a huge old coal engine out back lying on its side. All the trees there are bone trees.

The Belvedere Oasis. Somewhere between Albany and Chicago. An oasis is like if a mall fucked a rest stop and they had a fucked up baby that you can only access from the highway. Every time I stop at the Belvedere Oasis I happen to have a ridiculous amount of stuff in the back of the truck. Last time it was this big aluminum tub with a wheelbarrow and a broken porch swing in it. The parking lot is indescribably vast, like the surface of an artificial moon. When I stop there I always make sure to get an Orange Julius (which I never finish).

…

These are places I wish I could take the goose to. I want it to see them, maybe as a kind of apology. Maybe I’m trying to make amends. Alas, today I can only drive us as far as Cave City. I have a job, of course, and other random shit to do, so it isn’t too often anymore that I get one of these question mark days that prods you with its emptiness to undertake a mission that lies rotting in the corner of your own heart.

I’m driving to Cave City the way a married couple talks about going on a second honeymoon while sitting in the living room of their comfy brick house having coffee and listening to the thunder and smiling at their dog. I guess what I mean is I am loving myself quietly from opposite ends of the couch. I’m not saying I’m never going to get there—I probably will. The goose and I are up past Bowling Green when I decide to pull off the road and park on a strip of gravel. The two of us get out and go sit in the back of the truck for a minute, admiring a barn. It’s around suppertime now and the sky is the color of a cotton candy Philly Swirl popsicle, warm blush and ice blue and glittering with a tinge of frost that appears to be floating down slowly onto the grass. There are baby birds chirping in a bush. I fool with the cuff of my sweatshirt where it’s sort of coming apart into little strings. The world looks so fucking impossible I almost expect to see languid fish gliding around in the sky, flame swallowing the barn like a pyre on a raft drifting out into the center of the grassy lake. I’m starting to believe that a tree is still a tree if it’s a bone tree, and a goose is still a goose.

Dinosaur world. The only other location is in a town called Plant City in Florida, funnily enough. There’s a large fake tyrannosaurus rex standing proudly by the side of I-65, accompanied by a sign that says “DINOSAUR WORLD! EXIT NOW!” And that’s how you know you’re near Cave City.

Guntown Mountain. I guess it’s a giant warehouse firearm retailer. I’ve only seen it from a distance because it’s up on a hill overlooking Cave City like a fortress holding Cave City’s protective god. Or its oracle, or its talisman.

The general store with a big yellow sign. The man at the counter wears an eyepatch and looks sort of like a goat that’s about to kick the shit out of you, but he’s kind and sells beautiful tobacco pipes.

We get back in the truck.

0 notes