#the psychologist in me wants to argue it's basically sensory adaptation

Note

The main thing I dislike about Lewis’ style nowadays is the fit of the pants. The long coat is a style he’s worn a lot recently but he looks good in it so I don’t mind it (also the coat he wore yesterday was very nice imo), but the whole outfit was kind of ruined by the pants. Too large and too long, they make him look shorter. Idk why he doesn’t get them tailored or why he gets them tailored like this loool so many potentially good outfits ruined

Ohhhh my hatred of the pants' fit is well known in these parts lol

I agree he looks good in the coat but it's still getting too repetitive for me. Most fits by themselves are fine but taken together? Where's the innovation? Where's the surprise? I've used the same metaphor from the same anecdote the last time but like I once explained to a guy I was working on my thesis with who was arguing all street furniture should be art déco because art déco is pretty : I think firs are pretty but in a fir forest I just see an indistinguishable mass of dark green whereas in a mixed forest every tree stands out. When everything looks the same it just becomes background noise.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

An enlightening examination of meditation and evolution in “Why Buddhism Is True”

Anyone who has attempted meditation only to discover that their mind whirs faster than an 8-year-old with a fidget spinner knows that sitting in peaceful silence is easier said than done. In his latest book, “Why Buddhism Is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment,” Robert Wright makes research-based arguments for why evolution is at the root of some of that struggle.

He also argues that meditation is a good antidote to some of the challenges our genetic past has left us with, and that it’s worth the difficulty.

Ahead of his appearance at the Tattered Cover’s LoDo store on Sept. 11, the bestselling author talked about his experiences with meditation, how emotions govern more than we realize, and why powdered-sugar doughnuts are a perfect example of life’s fleeting pleasures.

“Why Buddhism Is True,” by Robert Wright.

Q: What prompted you to write this book? I’m imagining a mid-meditation epiphany.

A: There was no epiphany like that. I‘d written a book on evolutionary psychology, so it was very much part of the way I thought about everything, including my own predicament and my own experiences. Writing “The Moral Animal” has made me more aware of some of these frustrations of being human. But although evolutionary psychology highlights those, it doesn’t tell you what to do about them, whereas Buddhism both highlights them and has a plan for doing something about them.

That first retreat brought such a dramatic transformation of my consciousness over the course of a week that I did resolve to write something about it. Now, as it happens, at that point I don’t know what I would have written, because I still didn’t know much about Buddhism! All I knew was that if you go spend a week meditating, devoid of all contact from the world, you can emerge in a much better mood and emerge as a person who is easier to get along with — which my wife noticed right away.

Of course the transformation is not permanent. The most you can hope is to hold onto some of that. This is really a dramatic thing — I was just way calmer than usual, way less judgmental than usual, much more tuned in to beauty. It was a radical change, and it would be unrealistic to hope to hang on to that — certainly without a lot of effort.

Q: What got you on the cushion in the first place? You mention having attention deficit disorder in the book, and for some people, sitting still and doing nothing would sound like torture.

A: I had periodically tried to meditate, since college, just every once in awhile. … I don’t know exactly why. I mean, maybe exploring Eastern philosophy and spirituality is something you’re supposed to do if you went to college in the ‘70s, which I did.

I have my share of the kinds of psychological issues that people experiment with meditation for: you’d like life to be better, you’d like to have less anxiety, you’d like to be less of a jerk. And my work with evolutionary psychology had made me more aware of those kinds of problems and the difficulty and absurdity of being human.

Q: When you boil evolution down to what gets genes into the next generation, is that being reductive? Is there more to it than that?

A: We were designed by natural selection to be good at getting genes into the next generation. … that’s part of the absurdity of it. What a ridiculous criteria to be designed by, right? … I mean, whatever your ancestors left you with, that’s crazy! But that’s the situation. That’s why I think of meditation and Buddhism as being somewhat of a rebellion from natural selection.

Q: What is the default mode network, and why is meditation such a good foil to it?

A: It’s the system that governs mind wandering. The default mode network is to some extent a fancy name for the part of your brain that does mind wandering. And mind wandering is the first thing you encounter if you’re trying to focus on your breath. That’s what it comes up in meditation.

As it happens, brain scans are good at sensing when the default mode network is working, so it’s become something you can study. And it’s shown that good meditators are very good at quieting down the default mode network, so it’s a good hallmark.

It’s a reminder that you are not in control. … If you pay attention, you realize that you’re not running the show. And a good example is mind wandering. You’re not deciding what to think next — the stuff is just popping in your head and taking you with it.

One of the big ironies of Buddhism is that once you accept that there is no CEO self to be in control, then you really can, ironically, gain some control.

Q: That reminds me of the section on how emotion drives reason rather than the other way around — even though we so often want reason to override emotion and feelings.

A: This is one of the ways that modern psychology tends to validate Buddhism. Lately psychologists have come to see that feelings infiltrate pretty much all of our thinking — more than we had realized — and play a bigger role in guiding our thinking than we had realized. Even when you think of yourself as being rational, you’re being guided. … Take something like attention deficit — if you pay attention to what’s distracting you when you try to work, it’s almost alway a feeling.

Once you’re aware of it, you can do something about it. But that is definitely a trend in psychology that has been long anticipated.

Related Articles

Book review: A master class in creative nonfiction

Book review: Projecting our own desires onto Yellowstone’s landscape

John Ashbery, celebrated and challenging poet, dies at 90

A rare Firehouse Subs deal, $5 pizza and other cheap things around Denver, Sept. 1-7

“My Absolute Darling”: A brutal novel about a tough teen girl

Q: So, powdered-sugar doughnuts. Are they your kryptonite?

A: (Laughs.) Well, chocolate.

Q: You mention that a lot, too.

A: Chocolate, which I just acknowledge my slavery to, basically, dark chocolate — I have it every day. But yeah, powdered-sugar doughnuts, I guess they’re my kryptonite … I think for a lot of people they exemplify the allure of sensory pleasure. They’re really well designed to be tempting. And they do have that feature, that the pleasure tends not to last all that long, and then often a downside ensues. But I find them about as tempting as any food I can think of.

Q: They also say something about our modern condition, because cavemen and women didn’t have doughnuts.

A: They definitely illustrate that, too — that human impulses designed for one environment can become problematic when put into a different environment. And they have a lot of company: all drugs, all junk food. And kind of in the same ballpark are all the novel situations that cause extreme anxiety, like public speaking or dropping your toddler off at a daycare center where you don’t know anybody — all these things that worked in a hunger-gatherer environment that don’t work now.

Q: It made me wonder what you think we’re evolving toward now. Is it still merely continuation of the species?

A: Genetic evolution works too slowly to save us. It adapts too slowly to have any value. So the hope lies with what’s called cultural evolution — and that includes religion and it includes meditation. I personally think we’re going to have to develop ways to transcend our nature, or to become aware enough of our nature not to be kind of blindly enslaved to it. And I think that’s important not just for reasons of happiness, but to keep social systems intact.

People are talking about political polarization, tribalism in America … I think all of those conflicts are driven by a kind of psychology of tribalism that the species is going to have to learn to transcend.

Q: Should everyone meditate?

A: I think it would be a better world if everyone did. I don’t think it’s the only path to learning how your mind works … but I think it’s an effective approach. One way or another, more and more people have to become aware of what’s happening in their own heads.

Robert Wright will be at the Tattered Cover in LoDo to talk about “Why Buddhism Is True” on Sept. 11 at 7 p.m. 1628 16th St., 303-436-1070, tatteredcover.com

from Latest Information http://www.denverpost.com/2017/09/09/why-buddhism-is-true-robert-wright-book-review-inrterview/

0 notes

Text

Further Notes on “Rethinking Discipline”

Last week I published an article arguing for a different hypothesis about how self-discipline works. The standard idea, which even had decent scientific backing, was that willpower was a resource that could be depleted like a fuel.

Now the evidence behind this view is a bit shakier, so I wanted to suggest an alternative: self-discipline is a competition between different “mental habits” or patterns of thinking, feeling and reacting.

This idea is a bit confusing. It’s certainly less intuitive than a fuel analogy to self-discipline. With an idea of fuel being consumed over short-term acts of self-discipline, it’s fairly simple to make predictions. The idea of a messy array of mental habits you’re only partially aware of and which get feedback both internally and from the environment, is not.

The article attracted some outside attention, so I thought I’d take a few moments to clarify what I think the similarities and differences are with the standard resource-based theory.

Side note: It goes without saying that this is speculative. I think there’s evidence in support of this hypothesis, but there’s a good chance it’s wrong either in details or on major points which would undermine some of these conclusions.

Similarities Between Resource-Based and Mental Habit-Based Theories of Will

Some commenters expressed that they believed the correct way to view willpower was of a model of progressive training. You exercise your self-discipline more, and it gets stronger.

Interestingly, this is actually a point of agreement between the two theories, although the mechanisms and specific implications are different.

In a resource-based theory, willpower is like a muscle. It gets fatigued in the short-term through use. Over the long-term, however, it will adapt and grow to lift more weight.

In a habit-based theory, willpower is a competition between different mental patterns. Pay attention to patterns you want to amplify, mindfully non-react to those you want to diminish, and over the long-run you should be able to make changes to the overall pattern of reaction, leading to greater self-discipline.

There are key differences in what these theories predict, however:

First, in a resource-based theory, willpower is drawn from a common store. This means all willpower is the same. Get better at resisting donuts and, presumably, you should get better at not procrastinating. Exhaust yourself by focusing really hard, and other, unrelated, acts of self-discipline will be harder for a brief time.

In a habit-based theory, however, the mechanism is subject to the same things we know about mental patterns in learning. Therefore, it’s quite likely that there will be considerably context-dependence and possible failures of transfer when moving from one domain of willpower to another.

Self-discipline would only cross over to the extent that the mental patterns overlap. For some things this might be true, but for many it won’t.

Second, a habit-based theory has stochastic control over attention as the variable which modulates success at resisting temptation, not a depleting resource. Given this view, assuming environmental feedback remains constant, it’s not the case that self-discipline is fatigued in the short-run from use.

My feeling is that this isn’t often a huge difference because, in many acts of self-discipline, environmental feedback does increase which makes resisting harder and harder. Exercising, for instance, may be a situation where as one’s body gets more and more tired, reactions to pain become harder to avoid.

However, it does lead to some interesting conclusions where, if the environmental feedback plateaus at some level, it might be the case where relatively non-stop performance of self-discipline becomes possible. Long-distance runners, for instance, have told me that they find the run, “mostly mental,” after a certain distance, implying that bodily feedback has reached some relative level of constancy and now they’re just playing a game of attention to prevent reacting to it while they finish their run. (Actual long-distance runners may want to weigh-in here if my description is fair.)

What Does Meditation Have to Do With Self-Discipline?

Mindfulness and meditation, seem to play two distinct possible roles here in relation to self-discipline.

The first is that mindfulness, the act of trying to be aware of what is going on in your consciousness at a given moment in time, rather than simply trying to execute upon or judge those experiences, may give one a greater awareness of what exactly are the patterns which precede certain reactions.

My own experience meditating put a lot of these patterns into sharp relief. I used to think I would squirm out of an uncomfortable position because of the sensations themselves. However, looking more closely, the timing actually corresponded to some kind of thought or impulse, often with content which didn’t relate to this specific moment but worries about the duration of pain or the worthiness of the task I’m trying to endure.

I think many of these patterns are really hard to spot. Even meditating nearly non-stop during my 10-day retreat, I only started to notice some of them after several days in. Chances are there are subtler patterns of feeling and reaction I’m still oblivious to. This is even more true when, in a normal, non-meditative environment, you’re constantly trying to do things and make decisions and deal with huge amounts of impinging sensory information.

The second role of mindfulness seems to be that it allows a more precise control over attention. Attention has a voluntary component and an involuntary component. Voluntary, because we have some choice about what we want to pay attention to in a given moment, based on our values, feelings and previous decisions.

Involuntary because we all exhibit what psychologists call orienting responses. These are involuntary jerks of attention to strong stimulus coming from outside of our previous sphere of attention. A phone ringing, someone saying your name, pain from your body or an enticing thought pattern all cause momentary orientations away from the previous object of attention.

In most activities, attention control is the means for achieving some other objective, rather than the goal in and of itself. However, in practicing mindfulness, either in meditation or in life, the “goal” (if you can call it that) is on directing the voluntary part of attention itself.

This may have a facilitating effect on diminishing mental patterns that normally create strong orienting responses. Deprived of their normal sequential pattern of reaction, they will diminish in strength over time, the same way that overt physical habits extinguish when you stop following them automatically.

One open question for me is whether the mechanism of voluntary attention is the same as the habit patterns one wishes to modulate or whether it is operated by a different type of circuitry in the brain that has different principles. If the former is true, it may be that attention control has the same problems of transfer as other mental patterns, and therefore requires context-specific training. Alternatively, it may be operated by more generalized circuits in the brain and be closer to a faculty, meaning that training in mindfulness in one context could generalize to another, even if the habit patterns one wishes to engage in or avoid reacting to are different.

The answer to this question may suggest how important meditation is versus mindfulness in everyday life. If voluntary attention control has hard transfer problems, mindfulness in everyday life would be the main focus with meditation serving as a basic training or activity to remind yourself how to be mindful. If, on the other hand, voluntary attention control is a more general faculty, meditation itself may do much of the work and the mindfulness in other areas would be simply a matter of turning it on.

This point may be a bit confusing, so I’ll reiterate the model:

There are different habit patterns. Some you want to pay attention to. Others you want to avoid reacting to. These are likely fairly context-dependent. Meaning self-discipline doesn’t transfer perfectly across domains.

The act of mindfulness is a mechanism for facilitating self-discipline. It deals with the act of voluntary attention control in the moment, rather than the outcome of broader behaviors. This may be a fairly general faculty, or it might be like the mental habit patterns and itself be highly context-dependent.

If attention control is context-dependent, that may mean everyday mindfulness (e.g. Power of Now) is more important than meditation (e.g. Vipassana). If attention control is relatively general, meditation is relatively more important because it’s an opportunity to exclusively develop this faculty, without the constraints of other tasks.

Why the Focus on Self-Discipline?

I constrained the initial discussion to self-discipline because this seemed like a really good example of mental habits and one in which the ideas contradict a more standard model.

However, this really isn’t limited to self-discipline. If there’s a much broader quality of amplifying some mental patterns and diminishing others, then one could presumably optimize for very different sets of values.

One of my major goals with meditation was to reduce anxiety. As my life has gotten more complex and more of my major life goals have been achieved, what I’ve been left with has been increasingly the category of problems in which my life would be better if I stopped worrying about them–rather than the category of problems solved by taking some concrete action towards their resolution.

For me, therefore, the quality in which this has played out has been from trying to redirect attention away from future concerns, plans and worries when that is unnecessary and inappropriate, and onto the task I’m working on or the current moment.

This isn’t usually the aim of self-discipline, but the operation of this seems to be much the same as what I’ve described above. It’s simply that my emphasis is on different sets of patterns.

Similarly, I could see this working for stimulating spontaneity or creativity in the same way. Spontaneity seems to me to require the combination of a great deal of attention paid to the current moment, where alternatives and opportunities can be spotted, along with a disinhibition of unconventional or new patterns of action.

Spontaneity is perceived as being almost the opposite of self-discipline, and yet, it seems to be amenable to the same basic mechanism of attenuating and amplifying mental habit patterns.

How Far Does This Go?

I’m so early in the process of exploring this, I’m not even sure if this hypothesis is correct, never mind how far it can lead with reasonable dedication.

It may turn out that there are strong biological imperatives in one’s mental circuitry, so plasticity has fairly sharp limits. You may not be able to prevent yourself from succumbing to some patterns, or if you do, the brain may compensate by amplifying a related pattern to fulfill the same biological need.

In the context of overt habits, I’ve written that many are “meta-stable.” Meta-stability is a physical term referring to when a certain state may not have any inclination to change, but minor perturbations will kick it out of that state. A pendulum hanging is stable. A pendulum balancing perfectly upside-down is meta-stable.

Similarly, there may be a biologically preset level of certain mental habits that mean full extinction of the pattern without further effort to maintain it is impossible. It may even mean that getting the mental pattern down to a quieter level is still very hard, depending on the pattern.

My suspicion, however, is that the range of changes one could make with this method are a lot broader than the normal variation you see across human societies (which is already quite broad). I believe this because most patterns are self-reinforcing. Without realizing it, you make existing patterns stronger, not less. This leads to addiction, in extreme cases, but even when we don’t label the behavior as addiction, there’s a strong compulsion to engage in it. Since most of these patterns are being amplified beneath your awareness, then it will be whatever underlying tendencies existed before that guide them.

Further Notes on “Rethinking Discipline” syndicated from https://pricelessmomentweb.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Photo

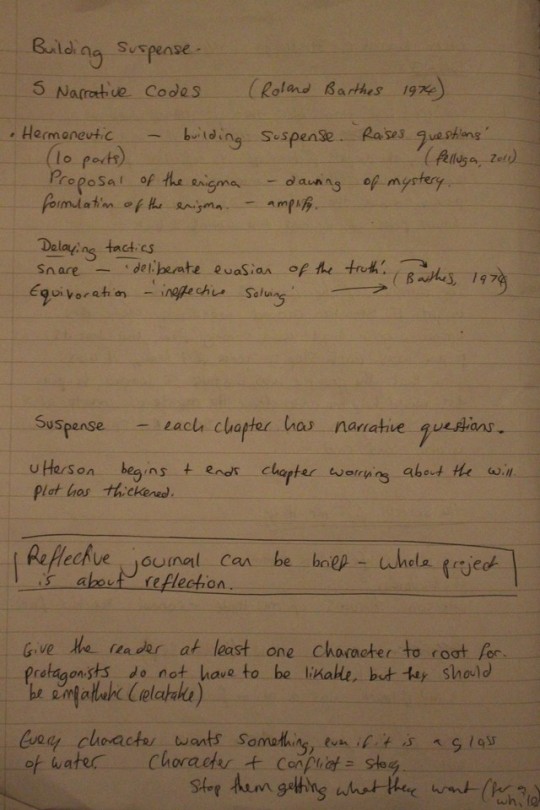

Narrative Strategies Week 3 (11/12/17):

This week we continued to look at narrative strategies for our project. We began with a short writing task to help us to practice writing short stories in preparation for our 500-word short story. The creative writing task was to write about rain. I used sensory words to describe the rain and the effect it has on clothing. I enjoyed writing about this, as I felt that I was able describe the feeling of rain without using the word ‘rain’ itself. I was pleased that I was able to describe something using sensory language, as I feel that this strengthens the narrative, and helps the audience to feel absorbed in the scene. We also had another writing task, this one to write about a dream (or start with a dream and adapt it) for 3 minutes. It was difficult for me to write this as I struggled to think of a dream that I had recently to write about. I decided to merge several dreams together to create a narrative that sounded exciting and creative, as I felt that small parts of my different dreams would fit together into one narrative. I decided to adapt parts of it so that it would be more interesting as a story, and I used a first person point of view to show how I would think or feel in the situation.

We looked at the second chapter of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Stevenson, 1886), The Search for Mr Hyde. In this chapter, Mr. Utterson has a dream about Mr. Hyde, as he wants to understand why Dr. Jekyll has a fondness for him. Utterson cannot see Hyde’s face in his dream. This foreshadows events in the novella, in a similar way to Stevenson himself - who dreamed about the events for Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. This chapter focuses on the unconscious mind and divided self, showing that characters may have hidden selves. Psychologist Sigmund Freud suggests that dreams show repressed desires that people have attempted to hide, suggesting that wish-fulfillment often occurred in dreams as people do not have to hide this side of their unconscious mind from people who may judge them. Freud argues that dreams have manifest (memories) and latent (symbolic) content which can suggest why we feel some dreams have meanings. In relation to Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Utterson’s dream suggests that he is obsessed with meeting Hyde.

In the novella, we are introduced to two more characters, Dr. Lanyon and Poole, Jekyll’s servant. Utterson visits Lanyon to ask him about Hyde. Whilst Utterson does not find out any information about Hyde, he ends up on better terms with the doctor, as he finds out their disagreement was over science. I feel that Dr. Lanyon is an interesting character, as his history with Utterson and Jekyll suggests that there is more to this character than what is described. I will consider writing about Dr. Lanyon for my 500-word short story, as I feel that this character would be interesting to create a story about, and using one of the themes in the book, I can create a different narrative for this character.

We also looked at how to use creative writing to create an appealing story. We looked at how to build suspense in a narrative using one of the 5 narrative codes, called the hermeneutic code (Roland Barthes, 1974). This is an unexplained element in the story that is answered within the story, which keeps the audience in suspense (Felluga, 2011). There are many different parts to the hermeneutic code:

Proposal of the enigma - the beginning of the mystery

Formulation of the enigma - the addition of elements that add to the mystery.

Request for an answer - the desire to answer the mystery (Silverman, 1984)

There are also ‘delaying tactics’ to draw out the suspense in a story:

Snare - a deliberate evasion of the truth (Barthes, 1974)

Equivocation - Something that is both true and false; ‘ineffective solving’ (Barthes, 1974)

Jamming - not being able to find an answer, which encourages the audience to keep following the story.

Suspended answer - a clear withholding of an answer.

Partial answer - providing an answer piece-by-piece. (Barthes, 1974. Silverman, 1984).

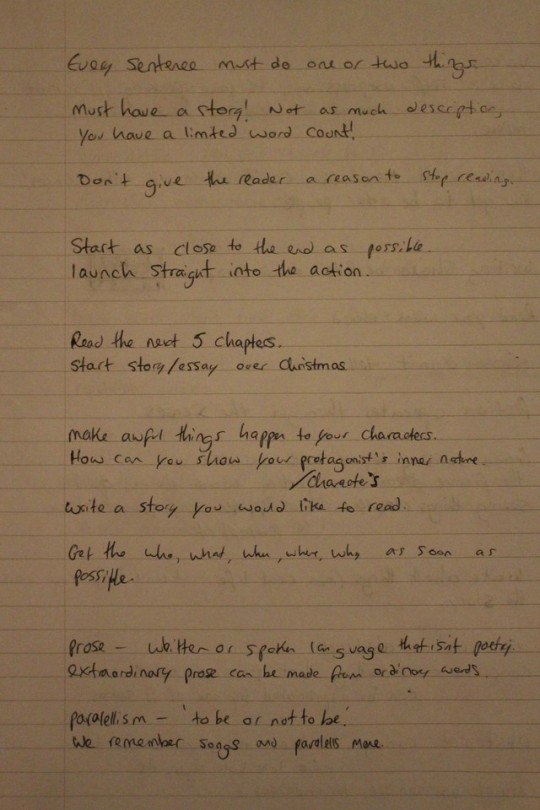

We also looked at Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 basics of short story writing to understand how we can apply this information to our own short stories.

Use the time of a stranger in a way that it does not feel as through it was wasted.

Give the reader a character to root for.

Every character should want something (even if it is a glass of water).

Every sentence should do one or two things - reveal the character, or advance the action.

Start as close to the end as possible.

Make awful things happen to the characters - to show the character’s inner nature.

Write to please one person (write what you would want to read).

Give the audience as much information as soon as possible - i.e. who, what, when, where, why (Konnegut, 1999).

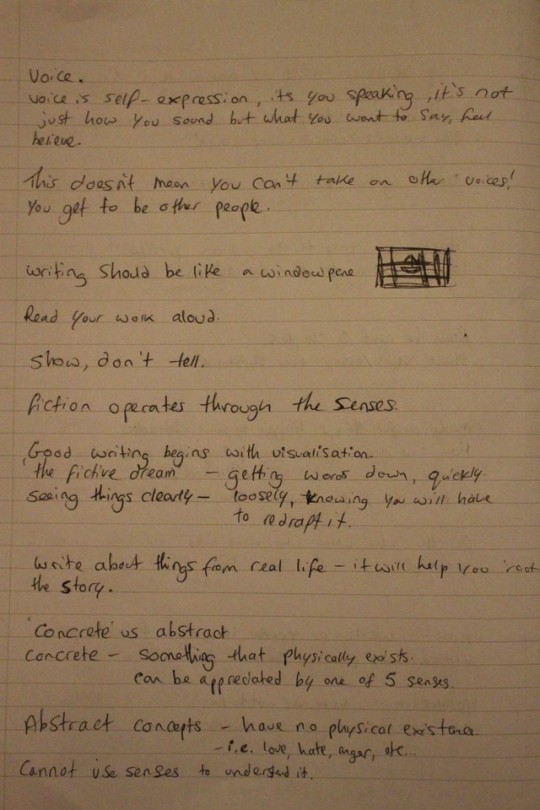

For my short story, I will write in a prose format. This will allow me to write a short story with enough detail to be an interesting narrative. We learned how reading our work aloud will help us to find the rhythm of it, which should help me to recognise where I need to edit my story. Within my writing, I should use concrete and abstract descriptive words to help me describe existing and sensory words respectively, as this will help me to improve the descriptions I include in my story.

For my task, I will need to read the next 5 chapters of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and write a point-of-view exercise from Mr. Hyde’s point of view of The Carew Murder Case. I will use sensory language to create my own version of Hyde’s account of the murder, and will use descriptive language to write it in a prose-style format.

Stevenson, R.L (1886) The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Other Tales of Terror (2002, 2003). London: Penguin Books.

Barthes, R (1974) S/Z. Translated by Richard Miller. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. Available at: https://monoskop.org/images/d/d6/Barthes_Roland_S-Z_2002.pdf

Felluga, D (2011) Modules on Barthes: on the Five Codes. Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. [Online] Available from: https://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/theory/narratology/modules/barthescodes.html

Silverman, K (1984) The Subject of Semiotics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://monoskop.org/images/0/0a/Silverman_Kaja_The_Subject_of_Semiotics_1984.pdf

Vonnegut, K. (1999) Bagombo Snuff Box. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. USA.

0 notes