#stand with the children of herat city

Text

“Almost a year ago, a 22-year-old girl named Mahsa Amini was killed by the morality police bc they didn't like she was showing her hair and the whole country erupted in protests. We thought we were going to overthrow the regime this time.

We were wrong.

The revolution didn't happen. We lost so many people. Thousands of people are in prison. And now the morality police is back on the streets. Kidnapping women who refuse to wear hijab and shoving them into the very same vans that killed Mahsa. It's like we're back where we started. But with so much loss and trauma.

I want to scream. But i feel I've been shoved into a bubble where every sound has been muted. I try to distract myself but the pain is relentless. I don't know how much of this pain and humiliation i can take.

And the world moves on. we are stuck here” @matarsack

#words of truth#true words#words to live by#mahsa amini#stand with the women of the middle east#stand for the women of the muslim world#stand with the women of afghanistan#stand with the children of herat city#stand with the children of iran#stand with the women of iran#stand with the girls of afghanistan#stand with the girls of the muslim world#stand with the children of afghanistan#protect women#burn the hijab

534 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer 2002 Road Trip: Kabul-Kandahar-Herat

Photos and imagery by Fariba Nawa

From the June 2004 issue of Afghan Magazine | Lemar-Aftaab

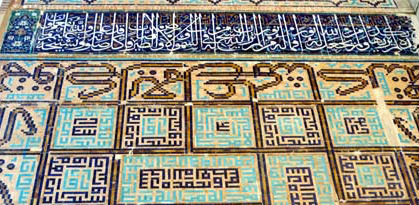

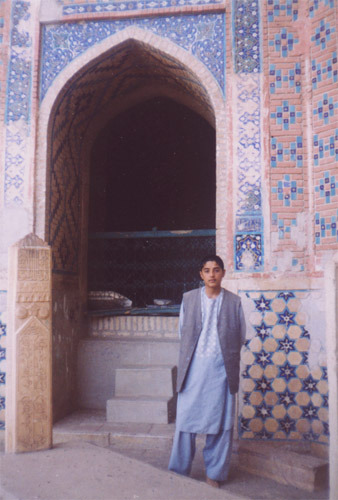

[caption: Tile work at the Gazargah shrine, Herat province.]

I traveled through Afghanistan in the fall of 2000 during the Taliban era and then returned in 2002 and 2003 to report for various publications and radio programs. These pictures are from the summer of 2002, when I took a cross-country road trip from Kabul, through Kandahar, and then to Herat, my hometown. This was before any roads were repaired, and during a time when many Afghans were still hopeful for change.

As a child, I lived in Kandahar, Helmand, and Herat. Now with American and European journalists as my travel mates, I traced back memories from my childhood, visiting sites like the Helmand River and the Gazergah shrine. I went to schools, shrines, bazaars, and private homes, talking to Afghans from every background and age to gauge the mood of the country.

We took a taxi on the road from Kandahar to Herat. It was a nine-hour ride through a dangerous zone where three people had been killed three days before. Our driver was easy-going, almost fearless, speeding at 90 mph on the cracked roads. We stopped for lunch at a roadside restaurant, and then our driver lit up his usual after-lunch joint. He smoked it as he drove.

My Spanish companion and I were not happy with his dessert. But our German photographer seemed amused. She was sitting in the front and taking photos of him.

"I can drive blindfolded through these roads," he told us with confidence.

Meanwhile, a group of turbaned men with Kalashnikovs jumped out from behind the small hills motioning us to stop with their guns. Our heartbeats accelerated as our car slowed to a stop. I had heard stories of road lootings, but this would be worse. We were all women and foreign women with a lot of cash on hand. We told the driver to keep going. He didn't listen. I somehow felt responsible for these women because I was the Afghan. A thousand things went through my mind. Will they rape us, kills us, and take our money? I clutched onto the door handle as one of the men stuck his head in the window and asked the driver for something in Pashtu.

I can barely understand Pashtu, but I could tell it was about money. We sat motionless, hoping the driver could rescue us. The driver handed the man a 40,000 afghani note, $1 then, said goodbye and drove off. The women looked dumbfounded. I asked the driver what had happened.

"They were just collecting toll. This is how people in this area make their money."

I wasn't sure whether to laugh or cry.

Join me on this journey.

Kabul

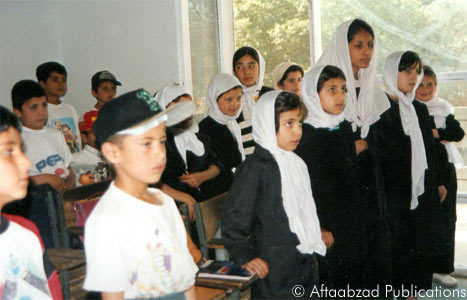

[caption: This is a co-education school in the Kabul neighborhood of Wazir Akbar Khan, which is one of the few areas in the capital left unscathed by war, although it suffers from years of neglect.]

[caption: A young girl gazes at the chalkboard absorbing the day's lessons.]

Kandahar

[caption: A view of the old city in Kandahar. Most Afghan cities and large towns are divided between old and new sections.]

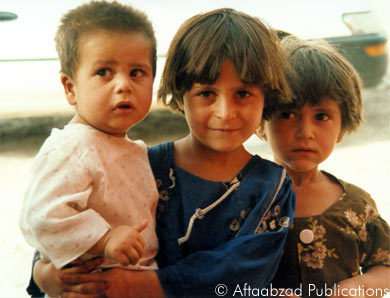

[caption: Children at the Kandahar bazaar. It is common to see small children out alone, running errands for their parents, and taking care of younger siblings.]

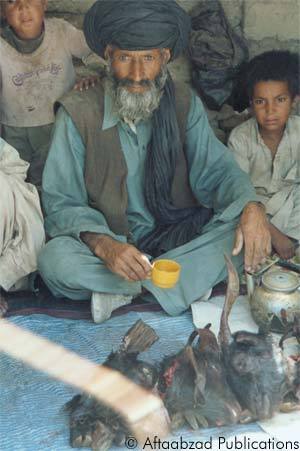

[caption: This bird seller at the Kandahar bazaar sells most of his birds to vendors who make them fight against each other, similar to cockfighting.]

[caption: A young office assistant at the World Food Program. During her downtime, she uses the computer to draw portraits. She wants to be an artist.]

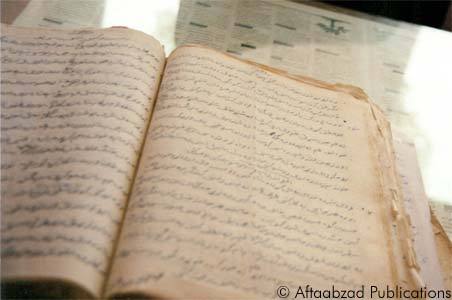

[caption: A 100-year-old Pashtu manuscript brought to the office of Culture and Information for preservation.]

[caption: Located near the old city of Kandahar, the Chihil Zina (Forty Steps) were built in the 16th century by Babur Shah, founder of the Moghul Empire. Inside the cave at the top of the steps, letters carved into the stone pay tribute to Babur Shah. This is one of Kandahar's most treasured historic sites.]

Kandahar to Herat

[caption: The bombed-out road from Kandahar to Herat. Drivers speed at 90 mph diving off the path to avoid destroyed bridges and then climbing back up. The drive takes nine hours to reach Herat city after passing three other provinces.]

[caption: Nasir, the driver for the Chicago Tribune, changes his seventh tire on the Tunis van. It took us about 17 hours from Kabul to Kandahar on the old, destroyed road. Now that the road has been rebuilt, the trip takes only five hours.]

[caption: Deserted Soviet army barracks. The fields are littered with mines en route to Herat.]

[caption: A taxi driver takes three women journalists, including me, from Kandahar to Herat. He rolls his joint and smokes his daily after-lunch hashish as he drives. "I can drive on this road with my eyes closed. Don't worry," he tells the frightened women.]

[caption: Camels are still common in rural Afghanistan. Nomads use them for transportation.]

Herat: Historic Sites

[caption: Around the majestic Friday Mosque in Herat City, men make colorful crafts including handmade silk shawls. This shawl reads "Herat 2002."]

[caption: One of the minarets built in Herat's cultural renaissance in the 15th century during Timurid rule. They encircle the Gowharshad shrine and school, another landmark from the same era.]

[caption: The Friday Mosque (Masjid-e Jami) is a sanctuary for Sufis and vagabonds. It is one of the cleanest public places in the city with gleaming handmade tiles and marble floors. It is among the finest Islamic buildings in the world. The structure is built on the platform of a Fire Temple dating back to the Zoroastrian period.]

[caption: The Friday Mosque's main entrance. The mosque is decorated with beautiful Timurid tilework and calligraphy.]

[caption: Another view of the Friday Mosque.]

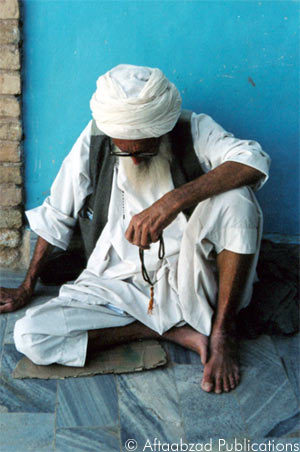

[caption: A malang (Sufi wanderer) in a trance at the Friday Mosque.]

[caption: Near the Friday Mosque are homes from a century ago. The architecture is common to the Islamic world with high ceilings, arches, and fountains in the courtyard. These homes are not being restored. Instead, Afghans are building boxy, whitewashed, modern-style houses modeled after those in Iran.]

[caption: This was once an indoor pool in one of the old houses.]

[caption: The family who lives in this house has been here for generations. But they are not sentimental about the fact that they have no running water or electricity.]

[caption: The view of the Friday Mosque from the roof of the old house.]

Herat: Crafts

[caption: In the corridors of the Friday mosque, workers bake and color tiles that will be used for the facades of other buildings in the city.]

[caption: A tile maker designs tiles.]

[caption: A finished tile looks something like the flower on the left.]

[caption: The glassblower of Herat. He has been blowing blue glass, an authentic Herati craft, for 30 years in front of the Friday Mosque. His young sons aid him in the laborious work, as they endure smoke and 120-degree heat inside a clay hut. "The foreigners come to see how interesting what I do is and how beautiful the glass turns out, but if I could trade this for another job, I'd take it in a second," he says.]

[caption: The father and his sons are busy at work.]

[caption: Designing the glass is a skillful task.]

[caption: Journalist Angeles Espinosa from Spain's premier newspaper El Pais visits the antique shop where the handmade glass is sold.]

Herat: City

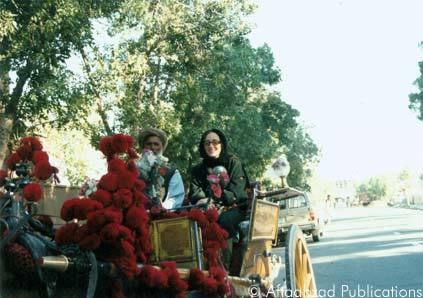

[caption: Riding in a horse wagon is a form of transportation in Herat.]

[caption: One of the many sparkling gardens rented out for private family parties on the outskirts of the city. Families gather here on Fridays to picnic and swim.]

[caption: Most homes in Herat have fruit trees and grapevines. Families pluck their dessert right from their yards.]

Herat: Education

[caption: Students at the Fine Arts College at Herat University. The classes are segregated by gender, but men and women study at the same university.]

[caption: Roia Hamid, a 26-year-old recent graduate of the Fine Arts College at Herat University, draws the image of a woman behind bars. Tears drip down from the sky to her face. "This is how I felt when the Taliban ruled here," Hamid says.]

[caption: Hamid's paintings. She copied this from a book lying around in her house.]

[caption: One of the students displays his work in the classroom. The men and women of the Fine Arts College organized a gallery exhibit. Some pieces sold for more than $1,000. The students are influenced by many art schools, including the classical school of Behzad, the 15th century Herati artist who established a unique style of miniature painting, often referred to as the "Rafael of the East".]

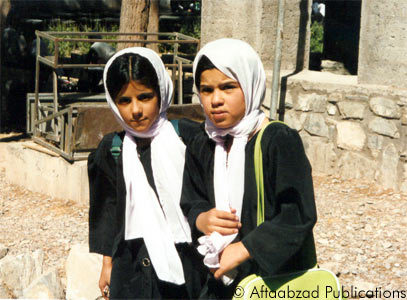

[caption: Young girls in school in uniform. At their age, a burka is not necessary.]

[caption: Classrooms in high schools are so full that students have to sit outside for exams. This group of girls is taking a geography test.]

Herat: Country and Camps

[caption: Ishaq Norzi, an Afghan who lives in Iran, visits his family land in Ghorian, a village two hours from Herat city.]

[caption: A young woman in Ghorian village, one of the most devastated areas in the province. It's one of the drug trafficking routes to Iran and the men and women in Ghorian live on the drug trade. This woman is an opium addict living in a clay hut in the desert.]

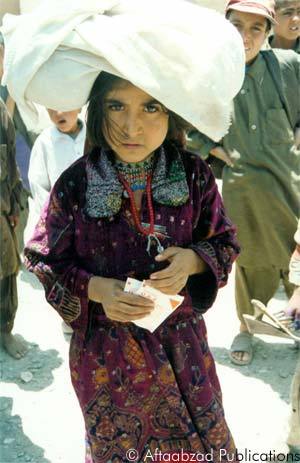

[caption: A young girl at the internally displaced refugee camp of Maslakh carries bread on her head. Many of the camps inside the country are closing as people return to their homes, but Maslakh remains open for the most down and out refugees.]

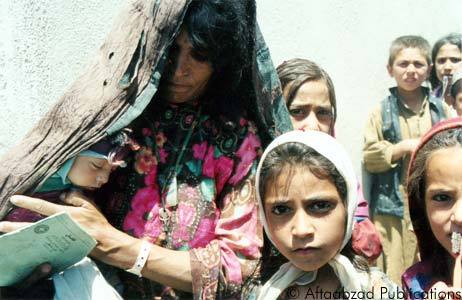

[caption: A mother and infant stand in line to see the camp doctor. Camp residents suffer from cholera, malaria, diarrhea, typhoid, and many other diseases. Ailments in the West that are easily treated become a death sentence to many in Afghanistan who have limited access to health care.]

[caption: The camp bazaar. Refugees find innovative merchandise to sell from sweets to blankets.]

[caption: Goat heads or is it sheep?]

[caption: Young girls take care of their younger siblings as if they are the mothers.]

[caption: Some girls shy away from the camera; others own it with their smile.]

[caption: Maslakh's brightest smiles and its hope.]

Herat: Gazargah

[caption: It is an honor to be buried in the cemetery next to the Gazergah shrine, located 3 miles east of Herat city. The 15th century Timurid ruler Shah Rukh built the complex of buildings around the shrine.]

[caption: The Gazergah shrine of Khoja Abdullah Ansary, the renowned 11th-century Sufi poet. Afghans from every walk of life gather here to pray and give alms. The shrine and its surrounding cemetery, mosque, and garden belong to the Mir family, descendants of the poet.]

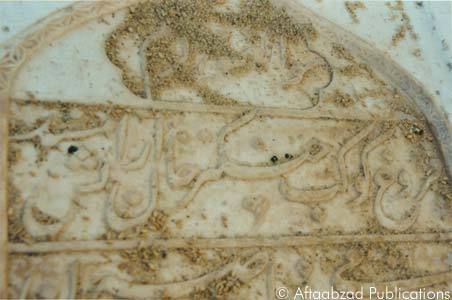

[caption: Centuries-old Persian calligraphy remains on the walls of the shrine.]

[caption: The gatekeepers of the shrine hid this statue of a lying dog from the Taliban. The architect who built the shrine represented himself as a dog to show his loyalty to the great poet, Ansary.]

[caption: Lavishly decorated tile work at the shrine.]

About Fariba Nawa فریبا نوا

Fariba Nawa, an award-winning Afghan-American journalist, covers a range of issues and specializes in women’s rights and conflict zones. She is based in Istanbul, Turkey and has traveled extensively to the Middle East, Central and South Asia. Visit Her Website

1 note

·

View note

Photo

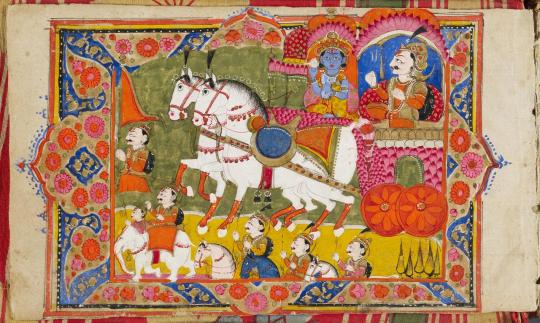

Gita is Krishnas Gift to Humanity

“Bhagavad Gita, also called the ‘holy song of the Lord’, is a gift given to the human society from Lord Sri Krishna to direct them towards seeking the higher goals of life...Bhagavad Gita can be compared to an intelligence agency. The word ‘intelligence’ means ‘inside information’. Any agency which has inside information about certain facts is an intelligence agency. Every country in this world has some intelligence agencies...All these agencies have access to information which common people do not have. Similarly, Bhagavad Gita gives us access to a range of inside information.

When Bhagavad Gita was spoken...Arjuna was a prince warrior, a householder with wife and children, having responsibilities of ruling the kingdom. However, Lord Krishna chose Arjuna to speak Bhagavad Gita...was spoken in the midst of the most gruesome impending war. Lord Krishna, however, chose to speak Bhagavad Gita in that situation by postponing the war.”

”[A] great warrior like Arjuna couldn’t tolerate even the insinuation of desertion and the cowardice it implied. Discouragement and internal state of mind had the power to take such a great hero to such a terrible state. Whether it is depression, dejection, or disheartenment—discouragement is one of our extremely dangerous enemies. For Arjuna even the thought of deserting and leaving the war was unconscionable.

Ralph Waldo Emerson says, “I owed a magnificent day to the Bhagavad Gita. It was the first of books; it was as if an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the same questions which exercise us.”

(via Gita is krishna’s gift to humanity- The New Indian Express)

Bhagavad Gita

“The Bhagavad Gita often referred to as the Gita...is set in a narrative framework of a dialogue between Pandava prince Arjuna and his guide and charioteer Krishna...Arjuna is filled with moral dilemma and despair about the violence and death the war will cause. He wonders if he should renounce and seeks Krishna's counsel, whose answers and discourse constitute the Bhagadvad Gita... The setting of the Gita in a battlefield has been interpreted as an allegory for the ethical and moral struggles of the human life.

The Gita in the title of the text "Bhagavad Gita" means "song"...the title has been interpreted as "the Song of God"..."the Song of the Lord", "the Divine Song", and "the Celestial Song"...the Bhagavad Gita suggests that it was composed in an era when the ethics of war were being questioned and renunciation to monastic life was becoming popular. Such an era emerged after the rise of Buddhism and Jainism in the 5th-century BCE...the first version of the Bhagavad Gita may have been composed in or after the 3rd-century BCE.”

Greco-Buddhism

“Greco-Buddhism, or Graeco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism, which developed between the 4th century BC and the 5th century AD in Bactria and the Indian subcontinent. It was a cultural consequence of a long chain of interactions begun by Greek forays into India from the time of Alexander the Great...Greco-Buddhism continued to flourish under the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, Indo-Greek Kingdoms, and Kushan Empire. Buddhism was adopted in Central and Northeastern Asia from the 1st century AD, ultimately spreading to China, Korea, Japan, Siberia, and Vietnam.

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (250–125 BC)...were followed by the Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 BC – AD 10). Even though the region was conquered by the Indo-Scythians and the Kushan Empire (1st–3rd centuries AD), Buddhism continued to thrive.Buddhism in India was a major religion for centuries until a major Hindu revival from around the 5th century, with remaining strongholds such as Bengal largely ended during the Islamic invasions of India. The length of the Greek presence in Central Asia and northern India provided opportunities for interaction, not only on the artistic, but also on the religious plane.”

“According to Ptolemy, Greek cities were founded by the Greco-Bactrians in northern India...A large Greek city built by Demetrius...at the archaeological site of Sirkap...where Buddhist stupas were standing side-by-side with Hindu and Greek temples, indicating religious tolerance and syncretism...In many parts of the Ancient World, the Greeks did develop syncretic divinities, that could become a common religious focus for populations with different traditions...Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence...Greek artists were most probably the authors of these early representations of the Buddha, in particular the standing statues, which display "a realistic treatment of the folds and on some even a hint of modelled volume that characterizes the best Greek work.

Intense westward physical exchange at that time along the Silk Road is confirmed by the Roman craze for silk from the 1st century BC to the point that the Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds...also wrote about Indo-Greek Buddhist king Menander, confirming that information about the Indo-Greek Buddhists was circulating throughout the Hellenistic world.”

“Although the philosophical systems of Buddhism and Christianity have evolved in rather different ways, the moral precepts advocated by Buddhism from the time of Ashoka through his edicts do have some similarities with the Christian moral precepts developed more than two centuries later: respect for life, respect for the weak, rejection of violence, pardon to sinners, tolerance.One theory is that these similarities may indicate the propagation of Buddhist ideals into the Western World, with the Greeks acting as intermediaries and religious syncretists.”

Hinduism

“Hinduism is the world’s oldest religion, according to many scholars, with roots and customs dating back more than 4,000 years. Today, with about 900 million followers, Hinduism is the third-largest religion behind Christianity and Islam. Roughly 95 percent of the world’s Hindus live in India...Hindus revere all living creatures and consider the cow a sacred animal.Food is an important part of life for Hindus. Most don’t eat beef or pork, and many are vegetarians.Hinduism is closely related to other Indian religions, including Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism.

Around 1500 B.C., the Indo-Aryan people migrated to the Indus Valley, and their language and culture blended with that of the indigenous people living in the region...The concept of dharma was introduced in new texts, and other faiths, such as Buddhism and Jainism, spread rapidly...In the 7th century, Muslim Arabs began invading areas in India. During parts of the Muslim Period, which lasted from about 1200 to 1757, Hindus were restricted from worshipping their deities, and some temples were destroyed. Saints expressed their devotion through poetry and songs.”

(via Hinduism | History Channel)

Ariana

“Ariana, the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek Ἀρ(ε)ιανή Ar(e)ianē (inhabitants: Ariani; Ἀρ(ε)ιανοί Ar(e)ianoi), was a general geographical term used by some Greek and Roman authors of the ancient period for a district of wide extent between Central Asia and the Indus River, comprising the eastern provinces of the Achaemenid Empire that covered the whole of modern-day Afghanistan, as well as the easternmost part of Iran and up to the Indus River in Pakistan (former Northern India).

The Greek term Arianē (Latin: Ariana), a term found in Iranian Avestan Airiiana- (especially in Airyanem Vaejah, the name of the Iranian peoples' mother country). The modern name Iran represents a different form of the ancient name Ariana which derived from Airyanem Vaejah and implies that Iran is “the” Ariana itself – a word found in Old Persian – a view supported by the traditions of the country preserved in the Muslim writers of the ninth and tenth centuries. The Greeks also referred to Haroyum/Haraiva (Herat) as 'Aria', which is one of the many provinces found in Ariana.

The names Ariana and Aria, and many other ancient titles of which Aria is a component element, are connected with the Avestan term Airya-, and the Old Persian term Ariya-, a self designation of the peoples of Ancient India and Ancient Iran, meaning "noble", "excellent" and "honourable".”

Aria (region)

“Aria is an Achaemenid region centered on the city of Herat in present-day western Afghanistan. In classical sources, Aria has been several times confused with the greater region of ancient Ariana, of which Aria formed a part. Aria was an Old Persian satrapy, which enclosed chiefly the valley of the Hari River... which in antiquity was considered as particularly fertile and, above all, rich in wine. The region of Aria was separated by mountain ranges...in the east...west...north... while a desert separated it...in the south...Its original capital was Artacoana or Articaudna according to Ptolemy. In its vicinity, a new capital was built, either by Alexander the Great himself or by his successors, Alexandria Ariana, modern Herat in northwest Afghanistan.”

Arya (Buddhism)

“Arya is a term frequently used in Buddhism that can be translated as "noble", "not ordinary", "valuable", "precious", "pure", etc. Arya in the sense of "noble" or "exalted" is frequently used in Buddhist texts to designate a spiritual warrior or hero.

The word "noble," or ariya, is used by the Buddha to designate a particular type of person, the type of person which it is the aim of his teaching to create. In the discourses the Buddha classifies human beings into two broad categories. On one side there are the puthujjanas, the worldlings, those belonging to the multitude...On the other side there are the ariyans, the noble ones, the spiritual elite, who obtain this status not from birth, social station or ecclesiastical authority but from their inward nobility of character....In Chinese Buddhist texts, ārya is translated as 聖 approximately, "holy, sacred"

Getes – the story to be told – Quotes

“The Spanish Chronicles...“The Daco-Getes are considered to be the founders of the Spaniards.”...The Chronicle of the Dukes of Normandy...“The Daco-Getes are considered to be the founders of the nordic nations.”...Collectanea Etymologica...“The Daco-Getes are considered to be the founders of the Teutons and Frisians, of the Dutch and Anglians.”...Cavasius (The Administration of the Kingdom of Transylvania): “In Italy, Spain and Galia, the peoples used to spoke an idiom of an older formation under the name of Rumanian language, as in the time of Cicero. The Rumanian language has more latinity than Italian.”

Bonaventura Vulcannius of Bruges, 1597: “The Getes had their own alphabet long before the Latin one was born. The Getes sang, using the flute, the deeds of their heroes, composing songs even before the foundation of Rome, that of which Cato says – the Romans started to do much later.”...Carolus Lundius...“It has to be clear for everyone, the ones who antiquity named them with a distinguished admiration Getes, the writers named them afterwards, through a unanimous agreement, Goths. The Greeks and other nations took letters from the Getes. We find with Herodotus and Diodorus, direct opinions about the spreading of these letters.”

“GET (pronounced ‘Jet’) = Earth-born. In Rumanian, the word ‘gețuitor’ (viețuitor) means ‘living man’. Earth = Geea/Gaia (Geb/Gebeleizis)...Djed = The forefathers of the first pharaohs of Egypt. Egyptians use this word Djed (pronounced ‘Jet’) when they speak of the ‘old ones’ that lived before them. Therefore this term has to do, not only with the Greeks. In Croatian the word ‘đed’ (pronounced ‘Jed’) means ‘grandfather’, which is another proof that the word ‘Get’ bears the meaning of ‘Old/Ancient’.

[T]he term ‘Gitia’ we have as a reconfirmation of the sacrality of its name, the Vedic opera Bhagavad Gītā (pronounced ‘Geeta’) which means ‘Song of the Lord’ or ‘Divine Song’ that speaks about the noble Aryans (‘Deva’ or ‘Devi’ meaning ‘The Divine’) which invaded the rich land of India...GETO = ‘The Brilliant’ or ‘The Divine’ or ‘The Wolves’, but they also have the meaning of ‘inhabitants of Davas’, where ‘Dava’ = ‘Fortress’. All these terms are in fact epithets that describe the Getes...The exonyms ‘Dac’/’Daki’ were used by the Romans to describe the Getes.”

(via Getes – the story to be told – Quotes | Vieille Europe blog)

Getae

“The Getae, or Gets (Ancient Greek: Γέται, singular Γέτης) were several Thracian tribes that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form Get and plural Getae may be derived from a Greek exonym: the area was the hinterland of Greek colonies on the Black Sea coast, bringing the Getae into contact with the ancient Greeks from an early date. Several scholars, especially in the Romanian historiography, posit the identity between the Getae and their westward neighbours, the Dacians.

There is a dispute among scholars about the relations between the Getae and Dacians, and this dispute also covers the interpretation of ancient sources. Some historians such as Ronald Arthur Crossland state that even Ancient Greeks used the two designations "interchangeable or with some confusion". Thus, it is generally considered that the two groups were related to a certain degree, the exact relation is a matter of controversy.”

Geats

“The Geats (/ˈɡiːts/, /ˈɡeɪəts/ or /ˈjæts/) (Old English: gēatas)...sometimes called Goths, were a North Germanic tribe who inhabited Götaland ("land of the Geats") in modern southern Sweden during the Middle Ages...Beowulf and the Norse sagas name several Geatish kings, but only Hygelac finds confirmation in Liber Monstrorum where he is referred to as "Rex Getarum"...Some decades after the events related in this epic...described the Geats as a nation which was "bold, and quick to engage in war"...The Hervarar saga is believed to contain such traditions handed down from the 4th century. According to that work, when the Hunnish Horde invaded the land of the Goths and the Gothic king Angantyr desperately tried to marshal the defenses, it was the Geatish king Gizur who answered his call, though there is no actual evidence of a successful invasion.

There is a hypothesis that the Jutes also were Geats, and which was proposed by Pontus Fahlbeck in 1884. According to this hypothesis the Geats would have not only resided in southern Sweden but also in Jutland, where Beowulf would have lived...Gēatas is the Old English form of Old Norse Gautar and modern Swedish Götar...in Beowulf, the Gēatas live east of the Dani (across the sea) and in close contact with the Sweon, which fits the historical position of the Geats between the Danes/Daci and the Swedes. Moreover, the story of Beowulf, who leaves Geatland and arrives at the Danish court after a naval voyage, where he kills a beast, finds a parallel in Hrólf Kraki's saga. In this saga, Bödvar Bjarki leaves Gautland and arrives at the Danish court after a naval voyage and kills a beast that has been terrorizing the Danes for two years (see also Origins for Beowulf and Hrólf Kraki)...As for the origins of the ethnonym Jute, it may be a secondary formation of the toponym Jutland, where jut is derived from a Proto-Indo-European root *eud meaning "water".

Bactria

“Bactria (/ˈbæktriə/); or Bactriana was a historical region in Central Asia. Bactria proper was north of the Hindu Kush mountain range and south of the Amu Darya river, covering the flat region that straddles modern-day Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and parts of Northern Pakistan. More broadly Bactria was the area north of the Hindu Kush.

After two years of war and a strong insurgency campaign, Alexander managed to establish little control over Bactria. After Alexander's death...Alexander's empire was divided up among the generals in Alexander's army. Bactria became a part of the Seleucid Empire, named after its founder, Seleucus I. The Macedonians, especially Seleucus I and his son Antiochus I, established the Seleucid Empire and founded a great many Greek towns. The Greek language became dominant for some time there.

The Greco-Bactrians were so powerful that they were able to expand their territory as far as India: As for Bactria, a part of it lies alongside Aria towards the north, though most of it lies above Aria and to the east of it. And much of it produces everything except oil. The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Bactria and beyond, but also of India.”

“Bactrians were the inhabitants of Bactria. Several important trade routes from India and China (including the Silk Road) passed through Bactria and, as early as the Bronze Age, this had allowed the accumulation of vast amounts of wealth by the mostly nomadic population. The first proto-urban civilization in the area arose during the 2nd millennium BC.

Control of these lucrative trade routes, however, attracted foreign interest, and in the 6th century BC the Bactrians were conquered by the Persians, and in the 4th century BC by Alexander the Great. These conquests marked the end of Bactrian independence. From around 304 BC the area formed part of the Seleucid Empire, and from around 250 BC it was the centre of a Greco-Bactrian kingdom, ruled by the descendants of Greeks who had settled there following the conquest of Alexander the Great.

The Greco-Bactrians, also known in Sanskrit as Yavanas, worked in cooperation with the native Bactrian aristocracy. By the early 2nd century BC the Greco-Bactrians had created an impressive empire that stretched southwards to include northwest India. By about 135 BC, however, this kingdom had been overrun by invading Yuezhi tribes, an invasion that later brought about the rise of the powerful Kushan Empire.”

Grand Trunk Road

“The Grand Trunk Road is one of Asia's oldest and longest major roads — founded around 3rd century BCE by the Mauryan Empire of ancient India. For more than two millennia, it has linked the Indian subcontinent with Central Asia.”

History of India

“[T]he White Huns were Turks, whose capital was ‘Organj or Khiva...The people called Yue-chi by the Chinese, Jits by the Tartars, and Getes or Getae by some of our writers, were a considerable nation in the centre of Tartary as late as the time of Tamerlane”

(via The History of India: The Hindu and Mahometan Periods p. 252)

Yuezhi

“The Yuezhi were an ancient Indo-European people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat by the Xiongnu in 176 BC, the Yuezhi split into two groups migrating in different directions: The Greater Yuezhi...later settled in Bactria, where they then defeated the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom.

The subsequent Kushan Empire, at its peak in the 3rd century CE, stretched from...the Tarim Basin, in the north to...the Gangetic plain of India in the south. The Kushanas played an important role in the development of trade on the Silk Road and the introduction of Buddhism to China...some scholars have associated the Yuezhi with artifacts of extinct cultures in the Tarim Basin, such as the Tarim mummies and texts recording the Tocharian languages.

[N]omadic pastoralists known as the Yúzhī...supplied jade to the Chinese...The export of jade from the Tarim Basin, since at least the late 2nd millennium BC...the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) bought jade and highly valued military horses from a people that Sima Qian called the Wūzhī...traded these goods for Chinese silk, which they then sold on to other neighbours. This is probably the first reference to the Yuezhi as a lynchpin in trade on the Silk Road, which in the 3rd century BC began to link Chinese states to Central Asia and, eventually, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Europe...The Lesser or Little Yuezhi moved to the "southern mountains", believed to be the Qilian Mountains on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, to live with the Qiang... Chinese sources continued to use the name Yuezhi and seldom used the Kushan as a generic term.”

“The central Asian people who called themselves Kushana, who were among the conquerors of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom during the 2nd century BC, are widely believed to have originated as a dynastic clan or tribe of the Yuezhi. Because some inhabitants of Bactria became known as Tukhāra (Sanskrit) or Tókharoi (Τοχάριοι; Greek), these names later became associated with the Yuezhi. The Kushana were a Caucasoid people...They spoke Bactrian, an Eastern Iranian language.

The Kushanas integrated Buddhism into a pantheon of many deities and became great promoters of Mahayana Buddhism, and their interactions with Greek civilization helped the Gandharan culture and Greco-Buddhism flourish. During the 1st and 2nd centuries, the Kushan Empire expanded militarily to the north and occupied parts of the Tarim Basin, putting them at the center of the lucrative Central Asian commerce with the Roman Empire...Following this territorial expansion, the Kushanas introduced Buddhism to northern and northeastern Asia, by both direct missionary efforts and the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese...and established translation bureaus, thereby being at the center of the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism.

"Tocharian"...became the common name for both the languages of the Tarim manuscripts and the people who produced them. Most historians now reject the identification of the Tocharians of the Tarim with the Tókharoi of Bactria, who are not known to have spoken any languages other than Bactrian. Other scholars suggest that the Kushanas may previously have spoken Tocharian before shifting to Bactrian on their arrival in Bactria.”

Kushan Empire

“The Kushan dynasty had diplomatic contacts with the Roman Empire, Sasanian Persia, the Aksumite Empire and Han Dynasty of China...the last of the Kushan and Kushano-Sasanian kingdoms were eventually overwhelmed by invaders from the north, known as the Kidarites.

The Kushans inherited the Greco-Buddhist traditions of the Indo-Greek Kingdom they replaced, and their patronage of Buddhist institutions allowed them to grow as a commercial power. Between the mid-1st century and the mid-3rd century, Buddhism, patronized by the Kushans, extended to China and other Asian countries through the Silk Road.

In 360 a Kidarite Hun named Kidara overthrew the Indo-Sasanians and remnants of the old Kushan dynasty, and established the Kidarite Kingdom. The Kushan style of Kidarite coins indicates they claimed Kushan heritage. The Kidarite seem to have been rather prosperous, although on a smaller scale than their Kushan predecessors. These remnants of the Kushan empire were ultimately wiped out in the 5th century by the invasions of the Hephthalites.”

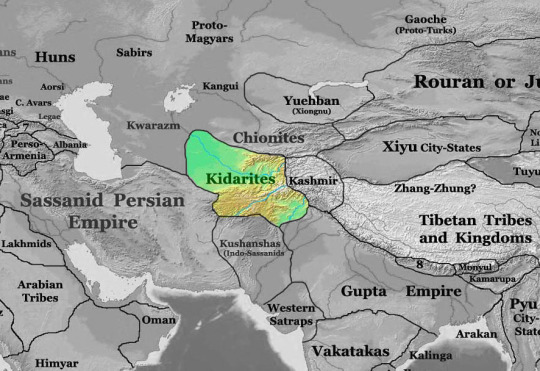

Kidarites

“The Kidarites were a dynasty that ruled Bactria and adjoining parts of Central Asia and South Asia in the 4th and 5th centuries CE. The Kidarites belonged to a complex of peoples known collectively in India as the Huna and/or in Europe as the Xionites...Named after Kidara, their founding ruler and purported membership of a clan named Ki, the Kidarites appear to have been a part of a Huna horde known in Latin sources as the Kermichiones (from the Iranian Karmir Xyon) or "Red Huna"...Indian records note that the Hūna had established themselves in modern Afghanistan and [north India]...The Kidarites are the last dynasty to regard themselves (on the legend of their coins) as the inheritors of the Kushan empire, which had disappeared as an independent entity two centuries earlier.”

Ghilji

“The Ghilji also called Khaljī, Khiljī, Ghilzai, or Gharzai (ghar means "mountain" and zai "born of"), are the largest Pashtun tribal confederacy...The Ghilji at various times became rulers of present Afghanistan region and were the most dominant Pashtun confederacy from c. 1000 AD until 1747 AD.”

Gilgit

“Gilgit, known locally as Gileet, is the capital city of the Gilgit-Baltistan region, an administrative territory of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, but claimed by India as its territory. The city is located in a broad valley near the confluence of the Gilgit River and Hunza River...It was an important stop on the ancient Silk Road, and today serves as a major junction along the Karakoram Highway with road connections to China, Skardu, Chitral, Peshawar, and Islamabad.”

“The city's ancient name was Sargin, later to be known as Gilit, and it is still referred to as Gilit or Sargin-Gilit by local people. In Brushaski, it is named Geeltand in Wakhi and Khowar it is called Gilt.

Gilgit was an important city on the Silk Road, along which Buddhism was spread from South Asia to the rest of Asia. It is considered as a Buddhism corridor from which many Chinese monks came to Kashmir to learn and preach Buddhism. Two famous Chinese Buddhist pilgrims, Faxian and Xuanzang, traversed Gilgit according to their accounts. According to Chinese records, between the 600s and the 700s, the city was governed by a Buddhist dynasty referred to as Little Balur or Lesser Bolü.

In mid-600s, Gilgit came under Chinese suzerainty after the fall of Western Turkic Khaganate due to Tang military campaigns in the region. In late 600s CE, the rising Tibetan Empire wrestled control of the region from the Chinese. However, faced with growing influence of the Umayyad Caliphate and then the Abbasid Caliphate to the west, the Tibetans were forced to ally themselves with the Islamic caliphates.”

“Gilgit manuscripts...containing many Buddhist texts such as four sutras from the Buddhist canon, including the famous Lotus Sutra. The manuscripts were written on birch bark...They cover a wide range of themes such as iconometry, folk tales, philosophy, medicine and several related areas of life and general knowledge.

The Gilgit manuscripts are included in the UNESCO Memory of the World register. They are among the oldest manuscripts in the world, and the oldest manuscript collection surviving in Pakistan, having major significance in the areas of Buddhist studies and the evolution of Asian and Sanskrit literature. The manuscripts are believed to have been written in the 5th to 6th centuries AD.

The former rulers had the title of Ra, and there is a reason to suppose that they were at one time Hindus, but for the last five centuries and a half they have been Moslems. The names of the Hindu Ras have been lost, with the exception of the last of their number, Shri Ba'dut...Gilgit was ruled for centuries by the local Trakhàn Dynasty, which ended about 1810 with the death of Raja Abas, the last Trakhàn Raja.”

Gilan Province

Gilan Province...lies along the Caspian Sea, in Iran... It seems that the Gelae (Gilites) entered the region south of the Caspian coast and west of the Amardos River (later Safidrud) in the second or first century B.C.E....the native inhabitants of Gilan have originating roots in the Caucasus is supported by genetics and language, as Gilaks are genetically closer to ethnic peoples of the Caucasus (such as the Georgians) than they are towards other ethnic groups in Iran. Their languages shares typologic features with Caucasian languages. It was the place of origin of the Buyid dynasty.”

“Gilan is mostly inhabited by Gilaks, a Gilaki Iranian culture is present in the province that is not much different from other Iranian traditions. The biggest differences are seen in foods, traditional songs, traditional clothes, rural areas and their every-day life, and other traditions such as the Gilaki Calendar and the Gilaki New Year called "Nouruz Bel" which is during the summer. This new year is distinct from the more popular Iranian New Year as it relates to the people of Gilan and their mostly agricultural life.”

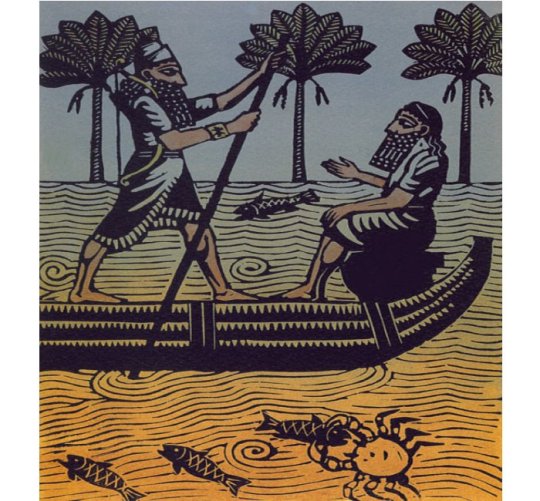

Epic of Gilgamesh

“The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia that is often regarded as the earliest surviving great work of literature. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian poems about Bilgamesh (Sumerian for "Gilgamesh"), king of Uruk, dating from the Third Dynasty of Ur(c. 2100 BC)."

“The first half of the story discusses Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, and Enkidu, a wild man created by the gods to stop Gilgamesh from oppressing the people of Uruk. After Enkidu becomes civilized through sexual initiation with a prostitute, he travels to Uruk, where he challenges Gilgamesh to a test of strength. Gilgamesh wins the contest; nonetheless, the two become friends. Together, they make a six-day journey to the legendary Cedar Forest, where they plan to slay the Guardian, Humbaba the Terrible, and cut down the sacred Cedar. The goddess Ishtar sends the Bull of Heaven to punish Gilgamesh for spurning her advances. Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the Bull of Heaven after which the gods decide to sentence Enkidu to death and kill him.

In the second half of the epic, distress over Enkidu's death causes Gilgamesh to undertake a long and perilous journey to discover the secret of eternal life. He eventually learns that "Life, which you look for, you will never find. For when the gods created man, they let death be his share, and life withheld in their own hands". However, because of his great building projects...Gilgamesh's fame survived well after his death with expanding interest in the Gilgamesh story which has been translated into many languages and is featured in works of popular fiction.”

The Origins Of Pearl Diving In The Persian Gulf

“Life in the Persian Gulf revolved around the natural pearl for centuries, according to archaeological evidence dating back to the Late Stone Age in 6000–5000 BC.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, a poem from 700 BC Mesopotamia that is among the first recorded examples of literary fiction, describes how the hero dived to the depths with weights tied to his feet for the “flower of immortality”, a well-known early allusion to pearling. By 100 AD, Pliny the Younger had declared that pearls were the most prized goods in Roman society, with those from the Gulf reigning as the most esteemed.

Pearl grounds originally stretched on the Arabian side from Kuwait along the coast of Saudi Arabia to Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and the Sultanate of Oman. They also ran along nearly the whole coast of the Persian side of the gulf, from near Bandar-e Bushehr (Kharg island) to Bandar-e Lengeh (Kish island) in the south and even further south into the Strait of Hormuz. The Phoenicians, who likely held the first monopoly on the pearl trade.”

Kish Island

“Kish Island has been mentioned in history variously as Kamtina, Arakia (Ancient Greek: Αρακία), Arakata, and Ghiss.Kish Island's strategic geographic location served as a way-station and link for the ancient Assyrian and Elamite civilizations when their primitive sailboats navigated from Susa through the Karun River into the Persian Gulf along the southern coastline, passing Kish, Qeshm, and Hormoz islands.

In 325 BC, Alexander the Great commissioned Nearchus to set off on an expeditionary voyage to the Sea of Oman and the Persian Gulf. Nearchus's writings on Arakata contain the first-known mention of Kish Island in antiquity. When Marco Polo visited the Imperial court in China, he commented on the Emperor's wife's pearls; he was told that they were from Kish.”

Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

“From the 4th century onward, Chinese pilgrims also started to travel on the Silk Road to India, the origin of Buddhism, by themselves in order to get improved access to the original scriptures...from the 4th century CE that Chinese Buddhist monks started to travel to India to discover Buddhism first-hand. Faxian's pilgrimage to India (395–414)...Xuanzang (629–644) and Hyecho traveled from Korea to India.”

“Buddhism in Central Asia began to decline in the 7th century in the course of the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana. A turning point was the Battle of Talas of 751. This development also resulted in the extinction of the local Tocharian Buddhist culture in the Tarim Basin during the 8th century. The Silk Road transmission between Eastern and Indian Buddhism thus came to an end in the 8th century...From the 9th century onward, therefore, the various schools of Buddhism which survived began to evolve independently of one another....In the eastern Tarim Basin, Central Asian Buddhism survived into the later medieval period as the religion of the Uyghur Kara-Khoja Kingdom...and Buddhism became one of the religions in the Mongol Empire...Central Asian Buddhism survived mostly in Tibet and in Mongolia.”

Key Monastery

“Kye Gompa (also spelled Ki, Key or Kee - pronounced like English key) is a Tibetan Buddhist monastery located on top of a hill...in the Spiti Valley of...India... Kye Gompa is said to have been founded by Dromtön (Brom-ston, 1008-1064 CE), a pupil of the famous teacher, Atisha, in the 11th century.”

Spiti Valley

“Spiti Valley is a cold desert mountain valley located high in the Himalayas...The name "Spiti" means "The Middle Land", i.e. the land between Tibet and India...Spiti valley is a research and cultural centre for Buddhists. Highlights include Key Monastery and Tabo Monastery, one of the oldest monasteries in the world and a favourite of the Dalai Lama...Spiti valley is accessible throughout year via Kinnaur...Due to high elevation one is likely to feel altitude sickness in Spiti.”

Epic of King Gesar

“The Epic of King Gesar, ("King Gesar" Mongolian: Гэсэр Хаан, Geser Khagan) also spelled Geser (especially in Mongolian contexts) or Kesar is an epic cycle, believed to date from the 12th century, that relates the heroic deeds of the culture hero Gesar...Its classic version is to be found in central Tibet.”

“Some 100 bards of this epic are still active today in the Gesar belt of China: Tibetan, Mongolian, Buryat, Balti, Ladakhi and Monguor singers maintain the oral tradition and the epic has attracted intense scholarly curiosity as one of the few oral epic traditions to survive as a performing art...versions of the epic are also recorded among the Balti of Baltistan, the Burusho people of Hunzaand Gilgit, and the Kalmyk and Ladakhi peoples, in Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and among various Tibeto-Burmese, Turkish, and Tunghus tribes.”

”It has been proposed on the basis of phonetic similarities that the name Gesar reflects the Roman title Caesar, and that the intermediary for the transmission of this imperial title from Rome to Tibet may have been a Turkic language, since kaiser (emperor) entered Turkish through contact with the Byzantine Empire, where Caesar (Καῖσαρ) was an imperial title. Some think the medium for this transmission may have been via Mongolian Kesar. The Mongols were allied with the Byzantines, whose emperor still used the title. Numismatic evidence and some accounts speak of a Bactrian ruler Phrom-kesar, specifically the Kabul Shahi of Gandhara, which was ruled by a Turkish From Kesar ("Caesar of Rome")... the Tibetan name Gesar derived from Sanskrit...the Ladakh variant of Kesar, Kyesar, in Classical Tibetan Skye-gsar meant 'reborn/newly born', and that Gesar/Kesar in Tibetan, as in Sanskrit signify the 'anther or pistil of a flower', corresponding to Sanskrit kēsara, whose root 'kēsa' (hair) is Indo-European.

King Ge-sar has a miraculous birth, a despised and neglected childhood, and then becomes ruler and wins his (first) wife 'Brug-mo through a series of marvellous feats. In subsequent episodes he defends his people against various external aggressors, human and superhuman. Instead of dying a normal death he departs into a hidden realm from which he may return at some time in the future to save his people from their enemies.”

#bhagvadgita#grecobuddhism#hinduism#silkroad#ariana#aria#arya#getes#geats#getae#syncretism#bactrian#yuezhi#keemonastary#kidarites#beowulf#gilgit#gilgamesh#kinggeser

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monday, September 27, 2021

COVID-19 vaccine boosters could mean billions for drugmakers

(AP) Billions more in profits are at stake for some vaccine makers as the U.S. moves toward dispensing COVID-19 booster shots to shore up Americans’ protection against the virus. How much the manufacturers stand to gain depends on how big the rollout proves to be. No one knows yet how many people will get the extra shots. But Morningstar analyst Karen Andersen expects boosters alone to bring in about $26 billion in global sales next year for Pfizer and BioNTech and around $14 billion for Moderna if they are endorsed for nearly all Americans.

So close! Iceland almost gets female-majority parliament

(AP) Iceland briefly celebrated electing a female-majority parliament Sunday, before a recount produced a result just short of that landmark for gender parity in the North Atlantic island nation. The initial vote count had female candidates winning 33 seats in Iceland’s 63-seat parliament, the Althing. Hours later, a recount in western Iceland changed the outcome, leaving female candidates with 30 seats. Still, at almost 48% of the total, that is the highest percentage for women lawmakers in Europe. Only a handful of countries, none of them in Europe, have a majority of female lawmakers. According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, Rwanda leads the world with women making up 61% of its Chamber of Deputies, with Cuba, Nicaragua and Mexico narrowly over the 50% mark. Worldwide, the organization says just over a quarter of legislators are women.

Copenhagen’s hippie, psychedelic oasis Christiania turns 50

(AP) After a half-century, the “flower-power” aura of Copenhagen’s semi-autonomous Christiania neighborhood hasn’t yet wilted. “It has become more and more an established part of Copenhagen,” said Ole Lykke, a resident of 42 years at the enclave near downtown Copenhagen. “The philosophy of community and common property still exists. Out here we do things in common.” It all started as a stunt 50 years ago, when a small counterculture newspaper that needed an outrageous story for its front page staged an “invasion” of an abandoned 18-century naval base. Six friends with air rifles and a picnic basket entered the former military facility base, proclaimed it a “free state” on Sept. 26, 1971, took some photos and went home. The paper ran the story, urging young people to take the city bus and squat the barracks. Hippies flocked to what they dubbed Christiania—no one remembers why they picked that name—that evolved into a counterculture, freewheeling oasis with psychedelic-colored buildings, free marijuana, limited government influence, no cars and no police. In 1973, it was recognized as a “social experiment.” After more than four decades of locking horns with authorities, Christiania’s future was secured in 2012 when the state sold the 84-acre (24-hectare) enclave for 85.4 million kroner ($13.5 million) to a foundation owned by its inhabitants. The residents—nearly 700 adults and about 150 children—now rent their homes from the foundation and are financially responsible for all repair and maintenance work to the roughly 240 buildings.

UK gas stations run dry as trucker shortage sparks hoarding

(AP) Thousands of British gas stations ran dry Sunday, an industry group said, as motorists scrambled to fill up amid a supply disruption due to a shortage of truck drivers. The Petrol Retailers Association, which represents almost 5,500 independent outlets, said about two-thirds of its members were reporting that they had sold out their fuel, with the rest “partly dry and running out soon.” Association chairman Brian Madderson said the shortages were the result of “panic buying, pure and simple.” “There is plenty of fuel in this country, but it is in the wrong place for the motorists,” he told the BBC. “It is still in the terminals and the refineries.” Long lines of vehicles formed at many gas stations over the weekend, and tempers frayed as some drivers waited for hours.

U.K.’s Migrant Boat Dispute Has Eyes Fixed on the Channel

(NYT) Using high-powered binoculars and a telescope, three volunteers from a humanitarian monitoring group stood on the Kent coast, peering across the English Channel. The looming clock tower of the French town of Calais was visible on this clear morning, but so was the distinctive outline of a small rubber dinghy. The volunteer group, Channel Rescue, was set up last year to watch for the boats packed with asylum seekers trying to cross this busy waterway, to offer them humanitarian support—like water and foil blankets—when they land on beaches, or to spot those in distress. But they are also monitoring Britain’s border authority for any possible rights violations as the government takes an increasingly hard line on migration. For much of the year, the numbers of migrants crossing the channel in dinghies has risen, brewing a political storm in London and leading Home Secretary Priti Patel to authorize tough tactics to push boats back toward France. The authorization—not yet put into effect—has stirred anew the national debate over immigration and created a further diplomatic spat between Britain and France, whose relations were already strained after Brexit over issues including both fishing rights and global strategic interests.

German elections

(AP) Germany is embarking on a potentially lengthy search for its next government after the center-left Social Democrats narrowly beat outgoing Chancellor Angela Merkel’s center-right bloc in an election that failed to set a clear direction for Europe’s biggest economy under a new leader. Leaders of the parties in the newly elected parliament were meeting Monday to digest a result that saw Merkel’s Union bloc slump to its worst-ever result in a national election, and appeared to put the keys to power in the hands of two opposition parties. Both Social Democrat Olaf Scholz, who pulled his party out of a years-long slump, and Armin Laschet, the candidate of Merkel’s party who saw his party’s fortunes decline in a troubled campaign, laid a claim to leading the next government. Scholz is the outgoing vice chancellor and finance minister and Laschet is the governor of Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia. Whichever of them becomes chancellor will do so with his party having won a smaller share of the vote than any of his predecessors.

Basta! Romans say enough to invasion of wild boars in city

(AP) Rome has been invaded by Gauls, Visigoths and vandals over the centuries, but the Eternal City is now grappling with a rampaging force of an entirely different sort: rubbish-seeking wild boars. Entire families of wild boars have become a daily sight in Rome, as groups of 10-30 beasts young and old emerge from the vast parks surrounding the city to trot down traffic-clogged streets in search of food in Rome’s notoriously overflowing rubbish bins. Posting wild boar videos on social media has become something of a sport as exasperated Romans capture the scavengers marching past their stores, strollers or playgrounds. Italy’s main agriculture lobby, Coldiretti, estimates there are over 2 million wild boars in Italy. The region of Lazio surrounding Rome estimates there are 5,000-6,000 of them in city parks, a few hundred of which regularly abandon the trees and green for urban asphalt and trash bins. In Italy’s rural areas, hunting wild boar is a popular sport and most Italians can offer a long list of their favorite wild boar dishes. Those beliefs are not shared by some urban residents.

Taiwan says China is a ‘bully’ after one of the largest PLA warplane incursions yet

(CNN) Taiwan on Thursday accused China of “bullying” after Beijing sent a total of 24 warplanes into its air defense identification zone (ADIZ), the third-largest incursion in the past two years of heightened tensions between Beijing and Taipei. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) aircraft, including bombers, fighter jets, anti-submarine planes and airborne early warning and control planes, entered Taiwan’s ADIZ in two groups—one of 19 planes and a second cohort of five jets that came later in the day. The air incursions came a day after Taiwan officially submitted an application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) free-trade pact. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs signaled its strong opposition to Taiwan’s application. “We firmly oppose official exchanges between any country and the Taiwan region, and firmly oppose Taiwan’s accession to any agreement or organization of an official nature,” ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said.

Taliban hang body in public; signal return to past tactics

(AP) The Taliban hanged a dead body from a crane parked in a city square in Afghanistan on Saturday in a gruesome display that signaled the hard-line movement’s return to some of its brutal tactics of the past. Taliban officials initially brought four bodies to the central square in the western city of Herat, then moved three of them to other parts of the city for public display, said Wazir Ahmad Seddiqi, who runs a pharmacy on the edge of the square. Taliban officials announced that the four were caught taking part in a kidnapping earlier Saturday and were killed by police, Seddiqi said. Since the Taliban overran Kabul on Aug. 15 and seized control of the country, Afghans and the world have been watching to see whether they will re-create their harsh rule of the late 1990s, which included public stonings and limb amputations of alleged criminals, some of which took place in front of large crowds at a stadium.

UN and Afghanistan’s Taliban, figuring out how to interact

(AP) It’s been little more than a month since Kalashnikov-toting Taliban fighters in their signature heavy beards, hightop sneakers and shalwar kameezes descended on the Afghan capital and cemented their takeover. Now they’re vying for a seat in the club of nations and seeking what no country has given them as they attempt to govern for a second time: international recognition of their rule. The Taliban wrote to the United Nations requesting to address the U.N. General Assembly meeting of leaders that is underway in New York. They argue they have all the requirements needed for recognition of a government. The U.N. has effectively responded to the Taliban’s request by signaling: Not so fast. Afghanistan, which joined the U.N. in 1946 as an early member state, is scheduled to speak last at the General Assembly leaders’ session on Monday. With no meeting yet held by the U.N. committee that decides challenges to credentials, it appears almost certain that Afghanistan’s current ambassador will give the address this year—or that no one will at all. The U.N. can withhold or bestow formal acknowledgement on the Taliban, and use this as crucial leverage to exact assurances on human rights, girls’ access to education and political concessions.

0 notes

Text

Taliban fighters in Kabul Foto: Rahmat Gul / AP

A Trillion Dollar Illusion

The Entirely Predictable Failure of the West's Mission in Afghanistan

In early July, I met with a leading Taliban military commander. I asked when his fighters would arrive in Kabul. His answer: "They are already there." How the Afghanistan mission failed and what happens next.

— By Christoph Reuter | 08.02.2021 | Spiegel International

In early July, before the great storm broke over Afghanistan, Kabul was already surrounded by the Taliban. And nowhere were the Islamist fighters closer to the Afghan capital city than on the shores of the Qargha Reservoir, a popular getaway on the western edge of the city. People were saying that the Taliban had gathered in the villages behind the nearby hills. The last frontline, it was said, was on the shore of the reservoir at the amusement park.

During the day, families were still taking their children to the rides and the restaurants or going out on the water in swan-shaped paddle boats. A small, six-member special forces unit even enjoyed a picnic in a wooden pavilion on the shore. One of them had to stand guard at the gun turret of their armored Humvee as the rest smoked hookahs and drank colorful sodas.

The next day, I met one of the Taliban’s leading military commanders for Kabul, who received me in the middle of the city in an unremarkable office building. When asked how far the Taliban had to walk to get to the lakeshore, he responded: "Not far at all." He seemed perfectly calm, a clean-shaven emissary of fear. "They’re already there, after all. They are the security guards at the restaurants, the ride operators, the cleaning staff. When the time is right, the place will be full of Taliban."

Six weeks after our meeting, in the middle of August, the same man drove to the Presidential Palace along with 10 bodyguards and the senior commander responsible for the conquering of Kabul. He hadn’t lied when he said that his men had already infiltrated the park at the reservoir. What he had failed to mention, though, was that the Taliban were also already in the heart of the city.

Numerous witnesses in various neighborhoods of the capital following the fall of Kabul had similar stories to tell. "It started in April," says a longtime acquaintance from the western part of the city. "More and more outsiders were suddenly in the neighborhood. Some had beards, others didn’t. Some were well dressed, others wore rags. Completely different. That made them difficult to notice. But all of the locals realized: They aren’t from here." They had silently infiltrated Kabul. The outsiders also appeared in the northern and eastern parts of the city, telling those who asked that they had come to Kabul for a new job or for business reasons.

Then, last Sunday morning, "they came out of the buildings holding white Taliban flags, some of them armed with pistols," says a resident of an eastern district of the city. It was the ultimate victory over America’s high-tech military, whose air surveillance proved powerless against this army of pedestrians and motorcyclists that would overrun Kabul from within and from outside in the ensuing hours. Later that day, they would drive through the city streets in captured police cars – from the air, an image of perfect confusion.

How could such a thing happen? How was it possible to lose Afghanistan to exactly the same group that was defeated – destroyed, really – in just two months back in 2001?

An anti-Taliban protest in Kabul on Thursday: The Taliban rolled in like an avalanche. Foto: Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times / Getty Images

For 20 years, the U.S. – together with Germany, Britain, Canada and other countries – maintained a presence in the country with its dominant military superiority and, at times, with over 130,000 troops. The Afghan army and police were trained and outfitted over and over again for a period equivalent to an entire generation – only to ultimately capitulate almost without a fight to an offensive of pedestrians. The takeover happened in the morning hours of last Sunday, with the Taliban suddenly appearing in Kabul like a ghost army.

It seems as though all of the efforts made in the last two decades – all of the roads, schools, wells and buildings that were built, all of the over $1 trillion that flowed into the country – were not enough to decisively sway the majority of Afghans to the side of the country’s financial backers.

It was like an avalanche from the north, beginning with the loss of several northern districts only to ultimately crash over the entire country, crushing the established state within just a few weeks. The first districts to fall were those with names hardly anyone in the West had ever heard before, but they were followed by entire provinces. Day after day, cities surrendered to the advance: Kunduz, Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kandahar. The more dramatic the collapse grew, the quieter it became as resistance faded away – until Kabul, the capital city cowering in fear, simply gave up within a matter of hours.

The shock was followed by panic. Tens of thousands of people rushed the walls of the Kabul airport in a desperate effort to escape the city and the country. The Taliban had long since closed down most of the overland border crossings through which people might have been able to escape to neighboring countries. Soon, the metal fences at the airport gave way. The guards vanished and masses of people forced their way onto the tarmac.

If images from the fall of Kabul have been burned into the world’s collective memory, it will be these ones: Men running alongside a slowly accelerating C-17 military cargo plane, desperately clinging to the landing gear of the taxiing jet. And then, a short time later, small figures losing their grip on the plane and falling to their deaths from hundreds of feet.

People at the airport in Kabul climbing on a plane belonging to the Afghan airline Kam Air. Foto: Wakil Kohsar / AFP

And then the triumphant victors driving through Kabul in pickups, their Kalashnikovs thrust into the air. Sauntering into the Presidential Palace and posing there as if it had always belonged to them. Ensuring the Afghans that they had no reason to be afraid, that they should carry on with their daily lives and nothing would happen to them. All they had to do, the Taliban insisted, was adhere to their rules.

Who is to blame for this disaster? Is it U.S. President Joe Biden, as his predecessor immediately trumpeted to the world? "It will go down as one of the greatest defeats in American history," Trump said, ignoring the fact that the deal he signed with the Taliban in February 2020 paved the way for the U.S. withdrawal.

Others saw the fall of Kabul as the "result of a large, organized and cowardly conspiracy," as Atta Mohammad Noor, the warlord and former governor of Mazar-e-Sharif, raged on Facebook following his precipitous helicopter escape. Ashraf Ghani, now the ex-president of Afghanistan, complained in an interview with DER SPIEGEL back in May of an "organized system of support" operated by Pakistan that was destabilizing his country. "The Taliban receive logistics there," Ghani said. "Their finances are there, and recruitment is there."

The list of accusations could continue. But the causes of this failure stretch back to the beginning of the invasion. The grumblers of today were themselves involved in this debacle, the most expensive act of self-deception of the century so far. Only those who understand how this disaster came about will be able to understand how things are likely to progress.

The term self-deception isn’t often used in its plural form, but it should be in the case of Afghanistan. The misconceptions from the West started at the very beginning of the intervention, when Washington thought the military would be sufficient to pacify the country, to the end, when Berlin was still asserting that it would only take just a bit longer to reverse the situation. Another fallacy was the assumption that a nation could be built and protected if enough money was invested and enough training undertaken. The Afghans, too, were guilty of self-deception, with the government and a large share of the population believing for two decades that the U.S. would never pull out.

Some lies served to obscure the true state of affairs in the country, others were the product of ignorance, and still others were truly believed. It was a fatal, collective delusion that ended up costing a six-figure number of Afghan lives along with those of more than 3,500 foreign troops. A fallacy that unintentionally sent Afghanistan on a 20-year detour from one Taliban reign to the next. Meanwhile, an entire generation grew up in the country’s cities under the assumption that the freedoms guaranteed by the foreign powers would be theirs forever.

These lines are born of the experience of having traveled to Afghanistan repeatedly over the course of 19 years and of having lived in Kabul as a correspondent for three of them. And they come from the sad realization that I wrote of the predictable failure of this project back in 2009. "If you take a look at the progression of the last eight years in Afghanistan, the following conclusion is unavoidable: The longer the international engagement there has lasted, the worse the situation has become," was my verdict at the time, "no matter how many thousands of kilometers of roads have been built, how many schools constructed and how many wells dug."

Nobody planned to stumble into this situation. The trigger for the mission was the shock of Sept. 11, 2001. Even as smoke was still rising from the rubble of the Twin Towers in New York, the masterminds of the biggest terror attack in recent history were discovered in Afghanistan. Al-Qaida leader Osama Bin Laden and his followers had developed a state within the "emirate" controlled by the Taliban. Washington’s primary goal was revenge and justice, not nation-building. Then German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder promised Germany’s "unlimited solidarity."

It was a different era, marked by the successes and horrors of the millennium that had just come to an end. The aftershocks of the euphoric events of 1989, when the Eastern Bloc managed to escape Moscow’s iron grip and Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary returned to democracy. On the other hand, the atrocities of Rwanda, the slaughter of 800,000 people as the UN stood by and watched, reinforced the idea of "never again." The NATO mission in Yugoslavia, which was controversial in Germany, managed to stop the Serbs in Kosovo. The Islamist Taliban movement, which ruled over most of Afghanistan following years of civil war, had been merely a side note to the horrors occurring elsewhere.

That was the situation immediately following Sept. 11 when Washington issued an ultimatum to the Taliban, demanding that they arrest and extradite bin Laden and the rest of the al-Qaida leadership or face the consequences. The Taliban said no. Whether they really meant no, and whether they might have been open to a face-saving plan whereby they would stand aside and allow Osama and the other leaders to be captured, as some from Taliban leadership would later claim, remains unsettled. NATO invoked Article 5, the collective defense mandate. The UN Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1368, legitimizing the coming attack as an act of self-defense.

The attack began on Oct. 7 with ballistic missiles, warplanes and B-2 long-range bombers targeting Kandahar and other targets in Afghanistan. The Northern Alliance, which joined the U.S. in the fight, arrived on horseback wielding Kalashnikovs. Kabul fell without a fight on Nov. 13 and Kandahar, where the Taliban got its start, followed on Dec. 7. The victory had taken just two months.

At the time, during this winter of fury, neither the voting public nor the government apparatus asked about plans for the future or the mission’s goals. In December 2001, the first Afghanistan Conference took place, an assembly of victors, some of whom dreamed of a return of King Mohammed Zahir Shah, who had been deposed in 1973. Missing from that initial gathering, as they would be from all subsequent meetings, were the Taliban. Nobody wanted them there.

I arrived in Afghanistan in the scorching hot summer of 2002, just after the U.S. Air Force had bombed a wedding party in the countryside. At least that’s what survivors said. The U.S. military spokesmen countered that gunmen onboard the U.S. aircraft had fired in self-defense after having been targeted from the ground.

That sounded so absurd that we went there ourselves, traveling unchallenged through the provinces of Kandahar, Helmand and Uruzgan, the cradle of the Taliban. But they were no longer there. "You know," an Afghan man said one evening around a fire at a rural rest stop, "I was also with the Taliban! But they’re history now." His tone was laconic, and he didn’t sound particularly disappointed, since he could now plant poppies again, something that had been strictly forbidden under Taliban rule.

In the bombed village in Uruzgan, it quickly became apparent that the story behind the wedding bombing had unfolded rather differently. The Americans hadn’t just attacked from the air, but had rolled in with a convoy of heavily armed infantrymen. It hadn’t been self-defense at all, but a planned attack. Members of a Kandahar tribe had accused allies of President Hamid Karzai of being members of the Taliban.

If you couldn’t defeat the Americans, you could apparently use them for your own purposes. It was a pattern that would repeat itself over and over again, and which would contribute to the abject failure of the intervention. The great tribal council meeting in Kabul in June 2002 "was the moment when it failed," recalls Thomas Ruttig, who was a UN official from Germany at the time, but who later co-founded the Afghanistan Analysts Network. "The moment when U.S. Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad brought back the warlords." They were the men who had destroyed the country in the earlier civil war, but who had helped the U.S. government of President George W. Bush in the fight against the Taliban.

Khalilzad and others forced the tribal council to include 50 additional men on top of the elected representatives – militia leaders who had ruled with fear and aggression before the arrival of the Taliban. They were men like Mohammed "Marshal" Fahim, a Tajik leader who stood accused of perpetrating massacres and kidnappings. And Rashid Dostum, the Uzbek leader who murdered several hundred imprisoned Taliban and later had his opponents raped with bottles. Both of them would go on to serve as vice president of the country. The new holders of power remained uncompromising. They immediately set about exacting revenge on their former enemies and plundering the new government.

A U.S. soldier trying to clear the tarmac at the Kabul Airport on Sunday. Foto: Wakil Kohsar / AFP

Billions of dollars earmarked for construction projects, roads and power plants would vanish in the ensuing years. Court verdicts could be bought, and rampant corruption corroded the state. Farmers, at least in the Pashtun provinces, remained poor and were bullied by the militias of the new rulers. The fighters would show up to hunt down the Taliban, but would then cut down the farmers’ almond trees and plunder their villages.

American and German politicians justified the eternal continuation of the military mission by claiming that the Taliban were "still there." But that wasn’t true. They slowly reappeared after several years of absence, first in the south and then in the north. Starting in 2007, I spent months with a former mullah documenting the Taliban’s slow return in his home district of Andar, south of Kabul. "The ill will toward everything foreign, toward Americans, toward Tajiks, toward police, was seamlessly nourished by real wrongs, exorbitant excesses and invented slights," we wrote at the time.

In the north, the German military rhapsodized at the time about the quiet in the provinces under their watch. When a new police chief was then appointed and he established a regime of horror in Kunduz, beating farmers and destroying their market stands when they didn’t pay sufficient protection money, the German troops stood by and watched from their hill overlooking the city. They were, they pointed out, only there as the "International Security Assistance Force" for the Afghanistan government. That presaged the return of the Taliban in Kunduz, with the Islamists taking control of village after village, until the Germans didn’t even dare to make forays six kilometers from their base. In September 2009, the German military called in U.S. airstrikes in Kunduz that killed 91 innocent people who were looting fuel from two hijacked tanker trucks. The German commander thought they were insurgents.

By then, Germany and the U.S. had invested so much capital, both financial and political, that they had become hostages of their own project. For the lack of other achievements, the international aid community in 2009 sold the mere holding of elections as a great triumph. But when more and more evidence began emerging of election fraud orchestrated by Karzai’s entourage, the West found itself stuck in an insoluble conundrum. If they recognized Karzai’s fraudulent election victory, they would be supporting an illegitimate government. If they did not, they would have to force out a government that they had spent billions of dollars supporting.

In the search for a solution, Washington overrode Karzai’s objections and pushed through a second vote, one that would be monitored by UN election observers. What then took place is among the darkest examples of the opportunism exhibited by the U.S. government and the UN.

At daybreak of Oct. 28, three attackers launched an assault on the UN guesthouse in Kabul, shot the guards to death, pushed their way into the courtyard and set about slaughtering the almost 30 UN employees inside. But they unexpectedly met resistance. Louis Maxwell, a former U.S. soldier and security officer, was able to hold back the attackers from a rooftop for one-and-a-half hours. No help came from the Afghan police or the army – right in the heart of Kabul. Once the three attackers set off their suicide belts, Maxwell staggered out, while four other UN employees were calling others on the outside telling them they would also emerge from hiding.