#same cook use to pop out back during a rush and power hit an american spirit

Text

being a line cook is insane but people do it anyway

do you want to know the secret to why line cooks stay line cooks?

We're addicted to a certain aspect of the job. A sort of combination of Pride and Power.

See, most of what is going on in that restaurant comes down to you. If the restaurant was a dairy, you'd be the cow, everything is based on what you produce; how much, how fast, and of what quality.

And it's INSANELY hard for most people to do. It requires you to keep mental track of tons of stuff while doing complicated physical creation in a dangerous environment under intense pressure

Any line cooks reading this? let me recreate a moment most of us have had many many times

For the rest of you this will be a nice window into the line cook experience

you have a rail FULL of tickets, and the printer will NOT stop printing more.

You've got a stove FULL of stuff you're cooking, and half of it is for stuff you don't even have a ticket for, because of something on a table that already went out was wrong or missing, or a server forgot to put something on a ticket and needs it in a hurry, or...

the tickets you are working on are for tables that finished their appetizers 45 minutes ago, and it could be an hour before you even get a chance to read whatever the printer is currently printing.

You have a head FULL of stuff you're tracking: how quickly the sauce is thickening in this pan, whether the garlic is about to burn in that pan, how long before you drain the pasta in that pot before it over cooks. As soon as the thing in the oven for table 31 is 5 minutes from done you gotta put the other thing on the flat top to go with it, you're putting together Something on your board and you can't finish it because you need a refill of an ingredient from the walk-in but you can't go get it because if you leave the kitchen you'll burn the thing in the salamander. And you can't plate the thing in salamander yet because the Something you're putting together on your board is taking up all the room you had left in this disaster of a kitchen

Three people have just told you complicated changes to dishes you have to organize and keep in your head. Something like

"24 needs 3 gnocchi not 4, and 2 with no rosemary; 3 needs all 4 gnocchi to have extra rosemary, 2 with no garnish; 22 needs an extra gnocchi extra garnish no rosemary, salads are almost out you can go in 3 or 4 minutes"

The manager, assistant manager, about 8 servers, and a fuckton of people at tables are all waiting on YOU with an impatience bordering on fury.

right? sound familiar? okay that's not the moment, that's just the dinner rush on a night somewhere between bad and average.

The moment happens when, during this insanity, you reach an internal place where you become completely overwhelmed. Panic and frustration and over stimulus all rise up and wipe your brain completely clean. You can't think, you have no idea what to do, you want to run away, you want to quit, you can barely think of your own name, everything feels completely impossible.

And then. The Moment

You pull it back together.

You stop being overwhelmed, you stop panicking, you insist that it IS possible, and that you are going to do it. You decide what has to happen and you start. You clear all the clutter you can from your kitchen. You pull all your tickets as far down the rail as possible and scan through the tickets on the printer so you have an idea of how things are going to go. You write down a couple of times on tickets that you would usually keep in your head but you need the brain space. You group the tickets according to not only time but what dishes they have in common so you can do batches of things. You decide if you can just get these two things out of your way you'll be in a much better position and so you concentrate on getting those two things cooked and plated. You beg the dishwasher to grab you the thing you need from the walk-in. You call your assistant manager or manager into the kitchen and you tell them you need them to start you 8 gnocchis: 3 no rosemary one extra garnish, 4 extra rosemary two no garnish, and one normal.

Right? Okay so first of all, as you can see... The job is INSANE

and second of all. Not everybody is capable of that Moment. The moment you stare already-existing catastrophic failure in the face and tell it No. That moment.

and you have to be capable of that moment if you want to be a line cook.

Which means pretty close to zero other people in that restaurant can do what you can do.

So now let me tell you a story.

I was 19 years old. I was a line cook at an italian joint. We're slammed off our ass one night, and the manager is in the little galley kitchen with me, and he's just standing there because he isn't good enough to not be in the way if he tries to help

and he's over my should about everything, telling me to drain that more or turn the heat down on this etc.

Finally, I stop completely, look him dead in the eye, and say "Tony, i'm not cooking another thing until you leave this kitchen."

I'm 19. Ive worked here six months. Tony is twice my age and married to the owner's daughter. There is a heavy pause.

Then Tony turns around and walks out of the kitchen.

What's he going to do, send me home? Zero other people in this restaurant can do the thing that makes it a restaurant. If i go home the customers are going home too.

And that's the real reason most line cooks stay line cooks even though the job feels like a war you never win.

It's that interplay of Pride and Power. For those few hours, the restaurant is happening because of you.

That's the power.

For the other part, try pulling a cook off the line during the rush. You can't. Even if they are in the weeds. Maybe even especially if they are in the weeds.

Once i was working with a cook who, in the middle of the dinner rush, sliced is hand open - a cut both deep and wide, pouring blood. No bandage we had was going to be a solution for it.

So he popped a latex glove on that hand, triple wrapped a rubber band around his wrist to keep the blood in, washed with soap, and went right back to cooking.

Because it was the dinner rush and no one else could do the job, and he wasn't coming off that line.

30 minutes in he had to swap gloves because it had filled with blood like a water balloon and was making it hard to cook. Leaving the line was never even a question.

that's the pride

#He went to the emergency room after his shift and came in to work two days later all stitched up and ready to kick more ass in the kitchen#same cook use to pop out back during a rush and power hit an american spirit#if you don't know american spirits are notoriously long lasting cigarets#and power hitting means smoking the whole cig in one long breath#that was my first restaurant job washing dishes there#wild experiences in restaurants absolutely wild

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

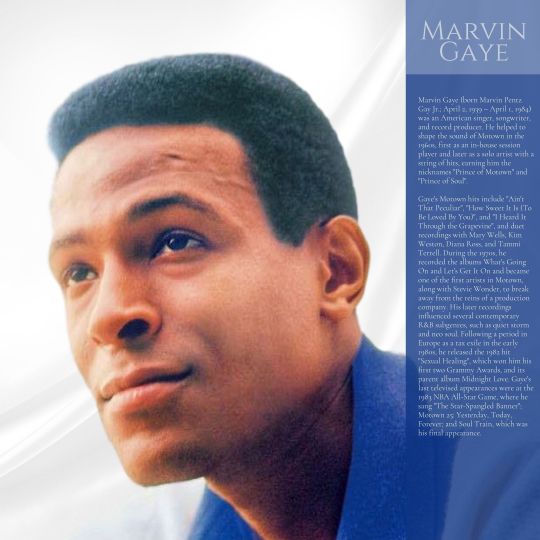

Marvin Gaye

Marvin Gaye (born Marvin Pentz Gay Jr.; April 2, 1939 – April 1, 1984) was an American singer, songwriter, and record producer. He helped to shape the sound of Motown in the 1960s, first as an in-house session player and later as a solo artist with a string of hits, earning him the nicknames "Prince of Motown" and "Prince of Soul".

Gaye's Motown hits include "Ain't That Peculiar", "How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)", and "I Heard It Through the Grapevine", and duet recordings with Mary Wells, Kim Weston, Diana Ross, and Tammi Terrell. During the 1970s, he recorded the albums What's Going On and Let's Get It On and became one of the first artists in Motown, along with Stevie Wonder, to break away from the reins of a production company. His later recordings influenced several contemporary R&B subgenres, such as quiet storm and neo soul. Following a period in Europe as a tax exile in the early 1980s, he released the 1982 hit "Sexual Healing", which won him his first two Grammy Awards, and its parent album Midnight Love. Gaye's last televised appearances were at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game, where he sang "The Star-Spangled Banner"; Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever; and Soul Train, which was his final appearance.

On April 1, 1984, the day before his 45th birthday, Gaye's father, Marvin Gay Sr., fatally shot him at their house in the West Adams district of Los Angeles. Many institutions have posthumously bestowed Gaye with awards and other honors including the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and inductions into the Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame, the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Early life

Gaye was born Marvin Pentz Gay Jr. on April 2, 1939, at Freedman's Hospital in Washington, D.C., to church minister Marvin Gay Sr., and domestic worker Alberta Gay (née Cooper). His first home was in a public housing project, the Fairfax Apartments (now demolished) at 1617 1st Street SW in the Southwest Waterfront neighborhood. Although one of the city's oldest neighborhoods, with many elegant Federal-style homes, Southwest was primarily a vast slum. Most buildings were small, in extensive disrepair, and lacked both electricity and running water. The alleys were full of one- and two-story shacks, and nearly every dwelling was overcrowded. Gaye and his friends nicknamed the area "Simple City", owing to its being "half-city, half country".

Gaye was the second oldest of the couple's four children. He had two sisters, Jeanne and Zeola, and one brother, Frankie Gaye. He also had two half-brothers: Michael Cooper, his mother's son from a previous relationship, and Antwaun Carey Gay, born as a result of his father's extramarital affairs.

Gaye started singing in church when he was four years old; his father often accompanied him on piano. Gaye and his family were part of a Pentecostal church known as the House of God. The House of God took its teachings from Hebrew Pentecostalism, advocated strict conduct, and adhered to both the Old and New Testaments. Gaye developed a love of singing at an early age and was encouraged to pursue a professional music career after a performance at a school play at 11 singing Mario Lanza's "Be My Love". His home life consisted of "brutal whippings" by his father, who struck him for any shortcoming. The young Gaye described living in his father's house as similar to "...living with a king, a very peculiar, changeable, cruel, and all powerful king." He felt that had his mother not consoled him and encouraged his singing, he would have killed himself. His sister later explained that Gaye was beaten often, from age seven well into his teenage years.

Gaye attended Syphax Elementary School and then Randall Junior High School. Gaye began to take singing much more seriously in junior high, and he joined and became a singing star with the Randall Junior High Glee Club.

In 1953 or 1954, the Gays moved into the East Capitol Dwellings public housing project in D.C.'s Capitol View neighborhood. Their townhouse apartment (Unit 12, 60th Street NE; now demolished) was Marvin's home until 1962.

Gaye briefly attended Spingarn High School before transferring to Cardozo High School. At Cardozo, Gaye joined several doo-wop vocal groups, including the Dippers and the D.C. Tones. Gaye's relationship with his father worsened during his teenage years, as his father would kick him out of the house often. In 1956, 17-year-old Gaye dropped out of high school and enlisted in the United States Air Force as a basic airman. Disappointed in having to perform menial tasks, he faked mental illness and was discharged shortly afterwards. Gaye's sergeant stated that he refused to follow orders. Gaye was issued a "General Discharge" from the service.

Career

Early career

Following his return, Gaye and his good friend Reese Palmer formed the vocal quartet The Marquees. The group performed in the D.C. area and soon began working with Bo Diddley, who assigned the group to Columbia subsidiary OKeh Records after failing to get the group signed to his own label, Chess. The group's sole single, "Wyatt Earp" (co-written by Bo Diddley), failed to chart and the group was soon dropped from the label. Gaye began composing music during this period.

Moonglows co-founder Harvey Fuqua later hired The Marquees as employees. Under Fuqua's direction, the group changed its name to Harvey and the New Moonglows, and relocated to Chicago. The group recorded several sides for Chess in 1959, including the song "Mama Loocie", which was Gaye's first lead vocal recording. The group found work as session singers for established acts such as Chuck Berry, singing on the hits "Back in the U.S.A." and "Almost Grown".

In 1960, the group disbanded. Gaye relocated to Detroit with Fuqua where he signed with Tri-Phi Records as a session musician, playing drums on several Tri-Phi releases. Gaye performed at Motown president Berry Gordy's house during the holiday season in 1960. Impressed by the singer, Gordy sought Fuqua on his contract with Gaye. Fuqua agreed to sell part of his interest in his contract with Gaye. Shortly afterwards, Gaye signed with Motown subsidiary Tamla.

When Gaye signed with Tamla, he pursued a career as a performer of jazz music and standards, having no desire to become an R&B performer. Before the release of his first single, Gaye was teased about his surname, with some jokingly asking, "Is Marvin Gay?" Gaye changed the spelling of his surname by adding an e, in the same way as did Sam Cooke. Author David Ritz wrote that Gaye did this to silence rumors of his sexuality, and to put more distance between himself and his father.

Gaye released his first single, "Let Your Conscience Be Your Guide", in May 1961, with the album The Soulful Moods of Marvin Gaye, following a month later. Gaye's initial recordings failed commercially and he spent most of 1961 performing session work as a drummer for artists such as The Miracles, The Marvelettes and blues artist Jimmy Reed for $5 (US$43 in 2019 dollars) a week. While Gaye took some advice on performing with his eyes open (having been accused of appearing as though he were sleeping), he refused to attend grooming school courses at the John Roberts Powers School for Social Grace in Detroit because of his unwillingness to comply with its orders, something he later regretted.

Initial success

In 1962, Gaye found success as co-writer of the Marvelettes hit, "Beechwood 4-5789". His first solo hit, "Stubborn Kind of Fellow", was later released that September, reaching No. 8 on the R&B chart and No. 46 on the Billboard Hot 100. Gaye reached the top 40 with the dance song, "Hitch Hike", peaking at No. 30 on the Hot 100. "Pride and Joy" became Gaye's first top ten single after its release in 1963.

The three singles and songs from the 1962 sessions were included on Gaye's second album, That Stubborn Kinda Fellow. Starting in October of the year, Gaye performed as part of the Motortown Revue, a series of concert tours headlined at the north and south eastern coasts of the United States as part of the Chitlin' Circuit. A filmed performance of Gaye at the Apollo Theater took place in June 1963. Later that October, Tamla issued the live album, Marvin Gaye Recorded Live on Stage. "Can I Get a Witness" became one of Gaye's early international hits.

In 1964, Gaye recorded a successful duet album with singer Mary Wells titled Together, which reached No. 42 on the pop album chart. The album's two-sided single, including "Once Upon a Time" and 'What's the Matter With You Baby", each reached the top 20. Gaye's next solo hit, "How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)", which Holland-Dozier-Holland wrote for him, reached No. 6 on the Hot 100 and reached the top 50 in the UK. Gaye started getting television exposure around this time, on shows such as American Bandstand. Also in 1964, he appeared in the concert film, The T.A.M.I. Show. Gaye had two number-one R&B singles in 1965 with the Miracles–composed "I'll Be Doggone" and "Ain't That Peculiar". Both songs became million-sellers. After this, Gaye returned to jazz-derived ballads for a tribute album to the recently-deceased Nat "King" Cole.

After scoring a hit duet, "It Takes Two" with Kim Weston, Gaye began working with Tammi Terrell on a series of duets, mostly composed by Ashford & Simpson, including "Ain't No Mountain High Enough", "Your Precious Love", "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing" and "You're All I Need to Get By".

In October 1967, Terrell collapsed in Gaye's arms during a performance in Farmville, Virginia. Terrell was subsequently rushed to Farmville's Southside Community Hospital, where doctors discovered she had a malignant tumor in her brain. The diagnosis ended Terrell's career as a live performer, though she continued to record music under careful supervision. Despite the presence of hit singles such as "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing" and "You're All I Need to Get By", Terrell's illness caused problems with recording, and led to multiple operations to remove the tumor. Gaye was reportedly devastated by Terrell's sickness and became disillusioned with the record business.

On October 6, 1968, Gaye sang the national anthem during Game 4 of the 1968 World Series, held at Tiger Stadium, in Detroit, Michigan, between the Detroit Tigers and the St. Louis Cardinals.

In late 1968, Gaye's recording of I Heard It Through the Grapevine became Gaye's first to reach No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. It also reached the top of the charts in other countries, selling over four million copies. However, Gaye felt the success was something he "didn't deserve" and that he "felt like a puppet – Berry's puppet, Anna's puppet...." Gaye followed it up with "Too Busy Thinking About My Baby" and "That's the Way Love Is", which reached the top ten on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1969. That year, his album M.P.G. became his first No. 1 R&B album. Gaye produced and co-wrote two hits for The Originals during this period, including "Baby I'm For Real" and "The Bells".

Tammi Terrell died from brain cancer on March 16, 1970; Gaye attended her funeral and after a period of depression, Gaye sought out a position on a professional football team, the Detroit Lions, where he later befriended Mel Farr and Lem Barney. It was eventually decided that Gaye would not be allowed to try out owing to fears of possible injuries that could have affected his music career.

What's Going On and subsequent success

On June 1, 1970, Gaye returned to Hitsville U.S.A., where he recorded his new composition "What's Going On", inspired by an idea from Renaldo "Obie" Benson of the Four Tops after he witnessed an act of police brutality at an anti-war rally in Berkeley. Upon hearing the song, Berry Gordy refused its release due to his feelings of the song being "too political" for radio. Gaye responded by going on strike from recording until the label released the song. Released in 1971, it reached No. 1 on the R&B charts within a month, staying there for five weeks. It also reached the top spot on Cashbox's pop chart for a week and reached No. 2 on the Hot 100 and the Record World chart, selling over two million copies.

After giving an ultimatum to record a full album to win creative control from Motown, Gaye spent ten days recording the What's Going On album that March. Motown issued the album that May after Gaye remixed portions of the album in Hollywood. The album became Gaye's first million-selling album launching two more top ten singles, "Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)" and "Inner City Blues". One of Motown's first autonomous works, its theme and segue flow brought the concept album format to rhythm and blues. An AllMusic writer later cited it as "...the most important and passionate record to come out of soul music, delivered by one of its finest voices." For the album, Gaye received two Grammy Award nominations and several NAACP Image Awards. The album also topped Rolling Stone's year-end list as its album of the year. Billboard magazine named Gaye Trendsetter of the Year following the album's success.

In 1971, Gaye signed a new deal with Motown worth $1 million (US$6,313,065 in 2019 dollars), making it the most lucrative deal by a black recording artist at the time. Gaye first responded to the new contract with the soundtrack and subsequent score, Trouble Man, released in late 1972. Before the release of Trouble Man, Marvin released a single called "You're the Man." The album of the same name was a follow up to What's Going On, but Motown refused to promote the single. Marvin later alleged that he and Gordy clashed over Marvin's political views, and for that reason, he was forced to shelve the album's release and substitute Trouble Man. However, Universal Music Group announced in 2019 that You're the Man would receive an official release. Around this period, he, Anna and Marvin III finally left Detroit and moved to Los Angeles permanently.

In August 1973, Gaye released the Let's Get It On album. Its title track became Gaye's second No. 1 single on the Hot 100. The album subsequently stayed on the charts for two years and sold over four million copies. The album was later hailed as "a record unparalleled in its sheer sensuality and carnal energy." Other singles from the album included "Come Get to This", which recalled Gaye's early Motown soul sound of the previous decade, while the suggestive "You Sure Love to Ball" reached modest success #14 on r&b charts but received tepid promotion due to the song's sexually explicit content.

Marvin's final duet project, Diana & Marvin, with Diana Ross, garnered international success despite contrasting artistic styles. Much of the material was crafted especially for the duo by Ashford and Simpson. Responding to demand from fans and Motown, Gaye started his first tour in four years at the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum on January 4, 1974. The performance received critical acclaim and resulted in the release of the live album, Marvin Gaye Live! and its single, a live version of Distant Lover, an album track from Let's Get It On.

The tour helped to enhance Gaye's reputation as a live performer. For a time, he was earning $100,000 a night (US$518,421 in 2019 dollars) for performances. Gaye toured throughout 1974 and 1975. A renewed contract with Motown allowed Gaye to build his own custom-made recording studio.

In October 1975, Gaye gave a performance at a UNESCO benefit concert at New York's Radio City Music Hall to support UNESCO's African literacy drive, resulting in him being commended at the United Nations by then-Ambassador to Ghana Shirley Temple Black and Kurt Waldheim. Gaye's next studio album, I Want You, followed in March 1976 with the title track "I Want You" becoming a No. 1 R&B hit. The album would go on to sell over one million copies. That spring, Gaye embarked on his first European tour in a decade, starting off in Belgium. In early 1977, Gaye released the live album, Live at the London Palladium, which sold over two million copies thanks to the success of its studio song, "Got to Give It Up", which became a No. 1 hit.

Last Motown recordings and European exile

In December 1978, Gaye released Here, My Dear, inspired by the fallout from his first marriage to Anna Gordy. Recorded with the intention of remitting a portion of its royalties to her as alimony payments, it performed poorly on the charts. During that period, Gaye's cocaine addiction intensified while he was dealing with several financial issues with the IRS. These issues led him to move to Maui, Hawaii, where he struggled to record a disco album. In 1980, Gaye went on a European tour. By the time the tour stopped, the singer relocated to London when he feared imprisonment for failure to pay back taxes, which had now reached upwards of $4.5 million (US$13,963,449 in 2019 dollars).

Gaye then reworked Love Man from its original disco concept to another personal album invoking religion and the possible end time from a chapter in the Book of Revelation. Titling the album In Our Lifetime?, Gaye worked on the album for much of 1980 in London studios such as Air and Odyssey Studios.

In the fall of that year, someone stole a master tape of a rough draft of the album from one of Gaye's traveling musicians, Frank Blair, taking the master tape to Motown's Hollywood headquarters. Motown remixed the album and released it on January 15, 1981. When Gaye learned of its release, he accused Motown of editing and remixing the album without his consent, allowing the release of an unfinished production (Far Cry), altering the album art of his request and removing the album title's question mark, muting its irony. He also accused the label of rush-releasing the album, comparing his unfinished album to an unfinished Picasso painting. Gaye then vowed not to record any more music for Motown.

On February 14, 1981, under the advice of music promoter Freddy Cousaert, Gaye relocated to Cousaert's apartment in Ostend, Belgium. While there, Gaye shied away from heavy drug use and began exercising and attending a local Ostend church, regaining personal confidence. Following several months of recovery, Gaye sought a comeback onstage, starting the short-lived Heavy Love Affair tour in England and Ostend in June–July 1981. Gaye's personal attorney Curtis Shaw would later describe Gaye's Ostend period as "the best thing that ever happened to Marvin". When word got around that Gaye was planning a musical comeback and an exit from Motown, CBS Urban president Larkin Arnold eventually was able to convince Gaye to sign with CBS. On March 23, 1982, Motown and CBS Records negotiated Gaye's release from Motown. The details of the contract were not revealed due to a possible negative effect on the singer's settlement to creditors from the IRS.

Midnight Love

Assigned to CBS's Columbia subsidiary, Gaye worked on his first post-Motown album titled Midnight Love. The first single, "Sexual Healing" which was written and recorded in Ostend in his apartment, was released on September 30, 1982, and became Gaye's biggest career hit, spending a record ten weeks at No. 1 on the Hot Black Singles chart, becoming the biggest R&B hit of the 1980s according to Billboard stats. The success later translated to the Billboard Hot 100 chart in January 1983 where it peaked at No. 3, while the record reached international success, reaching the top spot in New Zealand and Canada and reaching the top ten on the United Kingdom's OCC singles chart, later selling over two million copies in the U.S. alone, becoming Gaye's most successful single to date. The video for the song was shot at Ostend's Casino-Kursaal.

Sexual Healing won Gaye his first two Grammy Awards including Best Male R&B Vocal Performance, in February 1983, and also won Gaye an American Music Award in the R&B-soul category. People magazine called it "America's hottest musical turn-on since Olivia Newton-John demanded we get Physical." Midnight Love was released to stores a day after the single's release, and was equally successful, peaking at the top ten of the Billboard 200 and becoming Gaye's eighth No. 1 album on the Top Black Albums chart, eventually selling over six million copies worldwide, three million alone in the U.S.

I don't make records for pleasure. I did when I was a younger artist, but I don't today. I record so that I can feed people what they need, what they feel. Hopefully, I record so that I can help someone overcome a bad time.

On February 13, 1983, Gaye sang "The Star-Spangled Banner" at the NBA All-Star Game at The Forum in Inglewood, California—accompanied by Gordon Banks, who played the studio tape from the stands. The following month, Gaye performed at the Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever special. This and a May appearance on Soul Train (his third appearance on the show) became Gaye's final television performances. Gaye embarked on his final concert tour, titled the Sexual Healing Tour, on April 18, 1983, in San Diego. The tour ended on August 14, 1983 at the Pacific Amphitheatre in Costa Mesa, California but was plagued by cocaine-triggered paranoia and illness. Following the concert's end, he moved into his parents' house in Los Angeles. In early 1984, Midnight Love was nominated for a Grammy in the Best Male R&B Vocal Performance category, his 12th and final nomination.

Death

On the afternoon of April 1, 1984, in the family house in the West Adams district of Los Angeles, Gaye intervened in a fight between his parents and became involved in a physical altercation with his father, Marvin Gay Sr. In Gaye's bedroom minutes later, at 12:38 p.m. (PST), Gay Sr. shot Gaye in the heart and then, at point-blank range, his left shoulder. The first shot proved fatal. Gaye was pronounced dead at 1:01 p.m. (PST) after his body arrived at California Hospital Medical Center, one day short of his 45th birthday.

After Gaye's funeral, his body was cremated at Forest Lawn Memorial Park at the Hollywood Hills; his ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean. Initially charged with first-degree murder, Gay Sr.'s charges were dropped to voluntary manslaughter following a diagnosis of a brain tumor. Marvin Gay Sr. was later sentenced to a suspended six-year sentence and probation. He died at a nursing home in 1998.

Personal life

Gaye married Berry Gordy's sister, Anna Gordy, in June 1963. The couple separated in 1973, and Anna filed for divorce in November 1975. The couple were officially divorced in 1977. Gaye later married Janis Hunter in October 1977. The couple separated in 1979, and were officially divorced in February 1981.

Gaye was the father of three children, Marvin III (adopted with Anna; Marvin III was the son of Denise Gordy, Anna's niece), and Nona and Frankie, whom he had with his second wife, Janis. At the time of his death, he was survived by his three children, parents, and five siblings.

Musicianship

Equipment

Starting off his musicianship as a drummer doing session work during his tenure with Harvey Fuqua, and his early Motown years, Gaye's musicianship evolved to include pianos, keyboards, synthesizers, organs, bells, and finger cymbals. Gaye also utilized percussion instruments, such as box drums, glockenspiels, vibraphones, bongos, congas, and cabasas. This became evident when he was given creative control in his later years with Motown, to produce his own albums. In addition to his talent as a drummer, Gaye also embraced the TR-808, a drum machine that became prominent in the early 80's, making use of its sounds for production of his Midnight Love album. Despite his vast knowledge of instruments, the piano was his primary instrument when performing on stage, with occasional drumming.

Influences

As a child, Gaye's main influence was his minister father, something he later acknowledged to biographer David Ritz, and also in interviews, often mentioning that his father's sermons greatly impressed him. His first major musical influences were doo-wop groups such as The Moonglows and The Capris. Gaye's Rock & Roll Hall of Fame page lists the Capris' song, "God Only Knows" as "critical to his musical awakening." Of the Capris' song, Gaye said, "It fell from the heavens and hit me between the eyes. So much soul, so much hurt. I related to the story, to the way that no one except the Lord really can read the heart of lonely kids in love." Gaye's main musical influences were Rudy West of The Five Keys, Clyde McPhatter, Ray Charles and Little Willie John. Gaye considered Frank Sinatra a major influence in what he wanted to be. He also was influenced by the vocal styles of Billy Eckstine and Nat King Cole.

Later on as his Motown career developed, Gaye would seek inspiration in fellow label mates such as David Ruffin of The Temptations and Levi Stubbs of the Four Tops as their grittier voices led to Gaye and his producer seeking a similar sound in recordings such as "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" and "That's the Way Love Is". Later in his life, Gaye reflected on the influence of Ruffin and Stubbs stating, "I had heard something in their voices something my own voice lacked". He further explained, "the Tempts and Tops' music made me remember that when a lot of women listen to music, they want to feel the power of a real man."

Vocal style

Gaye had a four-octave vocal range. From his earlier recordings as member of the Marquees and Harvey and the New Moonglows, and in his first several recordings with Motown, Gaye recorded mainly in the baritone and tenor ranges. He changed his tone to a rasp for his gospel-inspired early hits such as "Stubborn Kind of Fellow" and "Hitch Hike". As writer Eddie Holland explained, "He was the only singer I have ever heard known to take a song of that nature, that was so far removed from his natural voice where he liked singing, and do whatever it took to sell that song."

In songs such as "Pride and Joy", Gaye used three different vocal ranges—singing in his baritone range at the beginning, bringing a lighter tenor in the verses before reaching a gospel mode in the chorus. Holland further stated of Gaye's voice that it was "...one of the sweetest and prettiest voices you ever wanted to hear." And while he noted that ballads and jazz was "his basic soul", he stated Gaye "...had the ability to take a roughhouse, rock and roll, blues, R&B, any kind of song and make it his own", later saying that Gaye was the most versatile vocalist he had ever worked with.

Gaye changed his vocal style in the late 1960s, when he was advised to use a sharper, raspy voice—especially in Norman Whitfield's recordings. Gaye initially disliked the new style, considering it out of his range, but said he was "into being produce-able." After listening to David Ruffin and Levi Stubbs, Gaye said he started to develop what he called his "tough man voice"—saying, "I developed a growl." In the liner notes of his DVD set, Marvin Gaye: The Real Thing in Performance 1964–1981, Rob Bowman said that by the early 1970s, Gaye had developed "three distinct voices: his smooth, sweet tenor; a growling rasp; and an unreal falsetto." Bowman further wrote that the recording of the What's Going On single was "...the first single to utilize all three as Marvin developed a radical approach to constructing his recordings by layering a series of contrapuntal background vocal lines on different tracks, each one conceived and sung in isolation by Marvin himself." Bowman found that Gaye's multi-tracking of his tenor voice and other vocal styles "summon[ed] up what might be termed the ancient art of weaving".

Social commentary and concept albums

Prior to recording the What's Going On album, Gaye recorded a cover of the song, "Abraham, Martin & John", which became a UK hit in 1970. Only a handful of artists of various genres had recorded albums that focused on social commentary, including Curtis Mayfield. Despite some politically conscious material recorded by The Temptations in the late 1960s, Motown artists were often told to not delve into political and social commentary, fearing alienation from pop audiences. Early in his career, Gaye was affected by social events such as the 1965 Watts riots and once asked himself, "with the world exploding around me, how am I supposed to keep singing love songs?" When the singer called Gordy in the Bahamas about wanting to do protest music, Gordy cautioned him, "Marvin, don't be ridiculous. That's taking things too far."

Gaye was inspired by the Black Panther Party and supported the efforts they put forth like giving free meals to poor families door to door. However, he did not support the violent tactics the Panthers used to fight oppression, as Gaye's messages in many of his political songs were nonviolent. The lyrics and music of What's Going On discuss and illustrate issues during the 1960s/1970s such as police brutality, drug abuse, environmental issues, anti-war, and black power issues. Gaye was inspired to make this album because of events such as the Vietnam War, the 1967 race riots in Detroit, and the Kent State shootings.

Once Gaye presented Gordy with the What's Going On album, Gordy feared Gaye was risking the ruination of his image as a sex symbol. Following the album's success, Gaye tried a follow-up album that he would label You're the Man. The title track only produced modest success, however, and Gaye and Motown shelved the album. Later on, several of Gaye's unreleased songs of social commentary, including "The World Is Rated X", would be issued on posthumous compilation albums. What's Going On would later be described by an AllMusic writer as an album that "not only redefined soul music as a creative force but also expanded its impact as an agent for social change". You're the Man was finally released on March 29, 2019, through Motown, Universal Music Enterprises, and Universal Music Group.

The What's Going On album also provided another first in both Motown and R&B music: Gaye and his engineers had composed the album in a song cycle, segueing previous songs into other songs giving the album a more cohesive feel as opposed to R&B albums that traditionally included filler tracks to complete the album. This style of music would influence recordings by artists such as Stevie Wonder and Barry White making the concept album format a part of 1970s R&B music. Concept albums are usually based on either one theme or a series of themes in connection to the original thesis of the album's concept. Let's Get It On repeated the suite-form arrangement of What's Going On, as would Gaye's later albums such as I Want You, Here, My Dear and In Our Lifetime.

Although Marvin Gaye was not politically active outside of his music, he became a public figure for social change and inspired/educated many people through his work.

Legacy

Marvin Gaye has been called "the number-one purveyor of soul music". In his book Mercy Mercy Me: The Art, Loves and Demons of Marvin Gaye, Michael Eric Dyson described Gaye as someone "...who transcended the boundaries of rhythm and blues as no other performer had done before." Following his death, The New York Times described Gaye as someone who "blended the soul music of the urban scene with the beat of the old-time gospel singer and became an influential force in pop music". Further in the article, Gaye was also credited with combining "the soulful directness of gospel music, the sweetness of soft-soul and pop, and the vocal musicianship of a jazz singer." His recordings for Motown in the 1960s and 1970s shaped that label's signature sound. His work with Motown gave him the titles Prince of Soul and Prince of Motown. Critics stated that Gaye's music "...signified the development of black music from raw rhythm and blues, through sophisticated soul to the political awareness of the 1970s and increased concentration on personal and sexual politics thereafter." As a Motown artist, Gaye was among the first to break from the reins of its production system, paving the way for Stevie Wonder. Gaye's late 1970s and early 1980s recordings influenced contemporary forms of R&B predating the subgenres quiet storm and neo-soul.

Artists from many genres have covered Gaye's music, including James Taylor, Brian McKnight, Kate Bush, Cyndi Lauper, Chico DeBarge, Michael McDonald, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, Aaliyah, Christina Aguilera, Phish, A Perfect Circle, The Strokes and Gil Scott-Heron. Other artists such as D'Angelo, Common, Nas, Erick Sermon, and Maxwell interpolated parts of Gaye's clothing from the singer's mid-1970s period. Gaye's clothing style was later appropriated by Eddie Murphy in his role as James "Thunder" Early in Dreamgirls. According to David Ritz, "Since 1983, Marvin's name has been mentioned—in reverential tones—on no less than seven top-ten hit records." Later performers such as Kanye West and Mary J. Blige sampled Gaye's work for their recordings.

Awards and honors

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducted him in 1987, declaring that Gaye "...made a huge contribution to soul music in general and the Motown Sound in particular." The page stated that Gaye "...possessed a classic R&B voice that was edged with grit yet tempered with sweetness." The page further states that Gaye "...projected an air of soulful authority driven by fervid conviction and heartbroken vulnerability." A year after his death, then-mayor of D.C., Marion Barry declared April 2 as "Marvin Gaye Jr. Memorial Scholarship Fund Day" in the city. Since then, a non-profit organization has helped to organize annual Marvin Gaye Day Celebrations in the city of Washington.

A year later, Gaye's mother founded the Marvin P. Gaye Jr. Memorial Foundation in dedication to her son to help those suffering from drug abuse and alcoholism; however she died a day before the memorial was set to open in 1987. Gaye's sister Jeanne once served as the foundation's chairperson. In 1990, Gaye received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In 1996, Gaye posthumously received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame listed three Gaye recordings, "I Heard It Through the Grapevine", "What's Going On" and "Sexual Healing", among its list of the 500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll. American music magazine Rolling Stone ranked Gaye No. 18 on their list of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time", sixth on their list of "100 Greatest Singers of All Time" and number 82 on their list of the "100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time". Q magazine ranked Gaye sixth on their list of the "100 Greatest Singers".

Three of Gaye's albums – What's Going On (1971), Let's Get It On (1973), and Here, My Dear (1978) – were ranked by Rolling Stone on their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. What's Going On remains his largest-ranked album, reaching No. 6 on the Rolling Stone list and topped the NME list of the Top 100 Albums of All Time in 1985 and was later chosen in 2003 for inclusion by the Library of Congress to its National Recording Registry. In addition, four of his songs – "I Heard It Through the Grapevine", "What's Going On", "Let's Get It On" and "Sexual Healing" – made it on the Rolling Stone list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

In 2005, Marvin Gaye was voted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame.

In 2006, Watts Branch Park, a park in Washington that Gaye frequented as a teenager, was renamed Marvin Gaye Park. Three years later, the 5200 block of Foote Street NE in Deanwood, Washington, D.C., was renamed Marvin Gaye Way. In August 2014, Gaye was inducted to the official Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame in its second class. In October 2015, the Songwriters Hall of Fame announced Gaye as a nominee for induction to the Hall's 2016 class after posthumous nominations were included. Gaye was named as a posthumous inductee to that hall on March 2, 2016. Gaye was subsequently inducted to the Songwriters Hall on June 9, 2016. In July 2018, a bill by California politician Karen Bass to rename a post office in South Los Angeles after Gaye was signed into law by President Donald Trump.

In popular culture

His 1983 NBA All-Star performance of the national anthem was used in a Nike commercial featuring the 2008 U.S. Olympic basketball team. Also, on CBS Sports' final NBA telecast to date (before the contract moved to NBC) at the conclusion of Game 5 of the 1990 Finals, they used Gaye's 1983 All-Star Game performance over the closing credits. When VH1 launched on January 1, 1985, Gaye's 1983 rendition of the national anthem was the very first video they aired. In 2010, it was used in the intro to Ken Burns' Tenth Inning documentary on the game of baseball.

"I Heard It Through the Grapevine" was played in a Levi's ad in 1985. The result of the commercial's success led to the original song finding renewed success in Europe after Tamla-Motown re-released it in the United Kingdom, Germany and the Netherlands. In 1986, the song was covered by Buddy Miles as part of a California Raisins ad campaign. The song was later used for chewing gum commercials in Finland and to promote a brand of Lucky Strike cigarettes in Germany.

Gaye's music has also been used in numerous film soundtracks including Four Brothers and Captain America: The Winter Soldier, both of which featured Gaye's music from his Trouble Man soundtrack. "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" was used in the opening credits of the film, The Big Chill.

In 2007, his song "A Funky Space Reincarnation" was used in the Charlize Theron–starred ad for Dior J'Adore perfume. A documentary about Gaye—What's Going On: The Marvin Gaye Story—was a UK/PBS co-production, directed by Jeremy Marre and was first broadcast in 2006. Two years later, the special re-aired with a different production and newer interviews after it was re-broadcast as an American Masters special. Another documentary, focusing on his 1981 documentary, Transit Ostend, titled Remember Marvin, aired in 2006.

Earnings

In 2008, Gaye's estate earned $3.5 million (US$4,156,182 in 2019 dollars). As a result, Gaye took 13th place in "Top-Earning Dead Celebrities" in Forbes magazine.

On March 11, 2015, Gaye's family was awarded $7.4 million in damages following a decision by an eight-member jury in Los Angeles that Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams had breached copyright by incorporating part of Gaye's song "Got to Give It Up" into their hit "Blurred Lines". In January 2016, the Gaye family requested a California judge give $2.66 million in attorneys' fees and $777,000 in legal expenses.

Gaye's estate is currently managed by Geffen Management Group and his legacy is protected through Creative Rights Group, both founded by talent manager Jeremy Geffen.

Attempted biopics

There have been several attempts to adapt Gaye's life story into a feature film. In February 2006, it was reported that Jesse L. Martin was to portray Gaye in a biopic titled Sexual Healing, named after Gaye's 1982 song of the same name. The film was to have been directed by Lauren Goodman and produced by James Gandolfini and Alexandra Ryan. The film was to depict the final three years of Gaye's life. Years later, other producers such as Jean-Luc Van Damme, Frederick Bestall and Jimmy De Brabant, came aboard and Goodman was replaced by Julien Temple. Lenny Kravitz was almost slated to playing Gaye. The script was to be written by Matthew Broughton. The film was to have been distributed by Focus Features and released on April 1, 2014, the thirtieth anniversary of Gaye's death. This never came to fruition and it was announced that Focus Features no longer has involvement with the Gaye biopic as of June 2013.

In June 2008, it was announced that F. Gary Gray was going to direct a biopic titled Marvin. The script was to be written by C. Gaby Mitchell and the film was to be produced by David Foster and Duncan McGillivray and co-produced by Ryan Heppe. According to Gray, the film would cover Gaye's entire life, from his emergence at Motown through his defiance of Berry Gordy to record What's Going On and on up to his death.

Cameron Crowe had also been working on a biopic titled My Name Is Marvin. The film was to have been a Sony presentation with Scott Rudin as producer. Both Will Smith and Terrence Howard were considered for the role of Gaye. Crowe later confirmed in August 2011 that he abandoned the project: "We were working on the Marvin Gaye movie which is called My Name is Marvin, but the time just wasn't right for that movie."

Members of Gaye's family, such as his ex-wife Janis and his son Marvin III, have expressed opposition to a biopic.

On December 9, 2015, Roger Friedman spoke of a biopic to be directed by F. Gary Gray that was approved by Berry Gordy and Suzanne de Passe as well as Gaye's family, following the success of Gray's Straight Outta Compton biopic based on the hip-hop act N.W.A.

In July 2016, it was announced that a feature film documentary on Gaye would be released the following year delving into the life of the musician and the making of his 1971 album, What's Going On. The film would be developed by Noah Media Group and Greenlight and is quoted to be "the defining portrait of this visionary artist and his impeccable album" by the film's producers Gabriel Clarke and Torquil Jones. The film will include "unseen footage" of the singer. Gaye's family approved of the documentary. In November 2016, it was announced that actor Jamie Foxx was billed to produce a limited biopic series on the singer's life. The series was approved by Gaye's family, including son Marvin III, who will serve as executive producer, and Berry Gordy, Jr..

On June 18, 2018, it was reported that American rapper Dr. Dre was in talks to produce a biopic about the singer.

Tributes

Acting

Gaye acted in two movies, both having to do with Vietnam veterans. One was in 1969 in the George McCowan-directed film, The Ballad of Andy Crocker which starred Lee Majors. The film was about a war veteran returning to find that his expectations have not been met and he feels betrayed. Gaye had a prominent role in the film as David Owens. The other was in 1971. He had a role in the Lee Frost-directed biker-exploitation film, Chrome and Hot Leather, a film about a group of Vietnam veterans taking on a bike gang. The film starred William Smith and Gaye played the part of Jim, one of the veterans. Gaye did have acting aspirations and had signed with the William Morris Agency but that only lasted a year as Gaye wasn't satisfied with the support he was getting from the agency.

Discography

Studio albums

The Soulful Moods of Marvin Gaye (1961)

That Stubborn Kinda Fellow (1963)

When I'm Alone I Cry (1964)

Hello Broadway (1964)

How Sweet It Is to Be Loved by You (1965)

A Tribute to the Great Nat "King" Cole (1965)

Moods of Marvin Gaye (1966)

I Heard It Through the Grapevine (1968)

M.P.G. (1969)

That's the Way Love Is (1970)

What's Going On (1971)

Trouble Man (1972)

Let's Get It On (1973)

I Want You (1976)

Here, My Dear (1978)

In Our Lifetime (1981)

Midnight Love (1982)

Collaborative albums

Together (with Mary Wells) (1964)

Take Two (with Kim Weston) (1966)

United (with Tammi Terrell) (1967)

You're All I Need (with Tammi Terrell) (1968)

Easy (with Tammi Terrell) (1969)

Diana & Marvin (with Diana Ross) (1973)

Filmography

1965: T.A.M.I. Show (documentary)

1969: The Ballad of Andy Crocker (television movie)

1971: Chrome and Hot Leather (television movie)

1973: Save the Children (documentary)

Videography

Marvin Gaye: Live in Montreux 1980 (2003)

The Real Thing: In Performance (1964–1981) (2006)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Step Into Your Feminine Power with the Wisdom of the Dakinis

How to Step Into Your Feminine Power with the Wisdom of the Dakinis:

Lama Tsultrim Allione—one of the first American woman ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun— shares what she’s learned about love, life, and liberty while researching dakinis, or fierce female messengers of wisdom.

Read the stories of the Dakini—fierce female messengers of wisdom in Tibetan Buddhism to tap into your feminine power.

When I was eleven, I ran home on the last day of school and tore off my dress, literally popping the buttons off, feeling simultaneously guilty and liberated. I put on an old, torn pair of cutoff jean shorts, a white T-shirt, and blue Keds sneakers, and ran with my sister into the woods behind our old colonial New Hampshire house. We went to play in the brook burbling down the steep hill over the mossy rocks, through the evergreens and deciduous trees, the water colored rich red-brown by the tannins in the leaves of the maple trees. We would play and catch foot-long white suckerfish with our hands, and then put them back because we didn’t want to kill them.

Sometimes we swam naked at night with friends at our summerhouse in the spring-fed lake 15 miles away, surrounded by pine, birch, spruce, and maple trees. I loved the feeling of the water caressing my skin like velvet, with the moon reflecting in the mirror-like lake. My sister and my friend Joanie and I would get on our ponies bareback and urge them into the lake until they were surging up and down with water rushing over our thighs and down the backs of the horses; they were swimming with us as we laughed, clinging onto their backs.

When violent summer thunderstorms blew through, instead of staying in the old wooden house I would run and dance outside in the rain and thunder, scaring my mother. I liked to eat with my fingers, gnawing on pork chop bones and gulping down big glasses of milk, in a hurry to get back outside. I loved gnawing on bones. My mother would shake her head, saying in desperation, “Oh, darling, please, please eat with your fork! Heavens alive, I’m raising a barbarian!”

See also This 7-Pose Home Practice Harnesses the Power of Touch

Barbarian, I thought, that sounds great! I imagined women with long hair streaming out behind them, racing their horses over wide plains. I saw streaked sunrises on crisp mornings with no school, bones to gnaw on. This wildness was so much a part of me; I could never imagine living a life that didn’t allow for it.

But then I was a wife and a mother raising two young daughters, and that wild young barbarian seemed lifetimes away. Paul and I had been married for three years when we decided to move from Vashon Island back to Boulder, Colorado, and join Trungpa Rinpoche’s community. It was wonderful to be in a big, active community with many young parents. However, the strain of the early years, our inexperience, and our own individual growth led us to decide to separate and collaborate as co-parents.

In 1978, I had been a single mother for several years when I met an Italian filmmaker, Costanzo Allione, who was directing a film on the Beat poets of Naropa University. He interviewed me because I was Allen Ginsberg’s meditation instructor, and Allen, whom I had met when I was a nun in 1972, introduced me to Costanzo. In the spring of 1979, we were married in Boulder while he was finishing his film, which was called Fried Shoes Cooked Diamonds, and soon thereafter we moved to Italy. I got pregnant that summer while we were living in a trailer in an Italian campground on the ocean near Rome, and that fall we moved into a drafty summer villa in the Alban Hills near the town of Velletri.

When I was six months pregnant, my belly measured the size of a nine-months pregnant woman’s, so they did an ultrasound and discovered I was pregnant with twins. By this time I knew that my husband was a drug addict and unfaithful. I couldn’t speak the native language and felt completely isolated. In March of 1980, I gave birth to twins, Chiara and Costanzo; they were a little early, but each weighed over five pounds. I buckled down to nursing two babies, caring for my other two daughters, and dealing with my husband’s addiction, erratic mood swings, and physical abuse, which started during my pregnancy when he began to hit me.

My feelings of overwhelm and anxiety increased daily, and I began to wonder about how my life as a mother and a Western woman really connected with my Buddhist spirituality. How had things ended up like this? How had I lost that wild, independent girl and left my life as a nun, ending up in Italy with an abusive husband? It seemed that by choosing to disrobe, I had lost my path, and myself.

Then two months later, on June 1, 1980, I woke up from a night of broken sleep and stumbled into the room where Chiara and her brother Costanzo were sleeping. I nursed him first because he was crying, and then turned to her. She seemed very quiet. When I picked her up, I immediately knew: she felt stiff and light. I remembered the similar feeling from my childhood, picking up my small marmalade colored kitten that had been hit by a car and crawled under a bush to die. Around Chiara’s mouth and nose was purple bruising where blood had pooled; her eyes were closed, but her beautiful, soft amber hair was the same and she still smelled sweet. Her tiny body was there, but she was gone. Chiara had died of sudden infant death syndrome.

See also Relieve Anxiety with a Simple 30-Second Practice

The Buddhist stupa of Swayambhu in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal.

The Dakini Spirit

Following Chiara’s death came what I can only call a descent. I was filled with confusion, loss, and grief. Buffeted by raw, intense emotions, I felt more than ever that I desperately needed some female guidance. I needed to turn somewhere: to women’s stories, to women teachers, to anything that would guide me as a mother, living this life of motherhood—to connect me to my own experience as a woman and as a serious Buddhist practitioner on the path. I needed the stories of dakinis—fierce female messengers of wisdom in Tibetan Buddhism. But I really didn’t know where to turn. I looked into all kinds of resources, but I couldn’t find my answers.

At some point in my search, the realization came to me: I have to find them myself. I have to find their stories. I needed to research the life stories of the Buddhist women of the past and see if I could discover some thread, some key that would help unlock the answers about the dakinis and guide me through this passage. If I could find the dakinis, I would find my spiritual role models—I could see how they did it. I could see how they made the connections between mother, wife, and woman … how they integrated spirituality with everyday life challenges.

About a year later, I was in California doing a retreat with my teacher, Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, who was teaching a practice called Chöd that involved invoking the presence of one of the great female masters of Tibetan Buddhism, Machig Labdrön. And in this practice there is an invocation, in which you visualize her as a young, dancing, 16-year-old white dakini. So there I was doing this practice with him, and for some reason that night he kept repeating it. We must have done it for several hours. Then during the section of the practice where we invoked Machig Labdrön, I suddenly had the vision of another female form emerging out of the darkness.

See also 10 Best Women-Only Yoga Retreats Around the World

What I saw behind her was a cemetery from which she was emerging. She was old, with long, pendulous breasts that had fed many babies; golden skin; and gray hair that was streaming out. She was staring intensely at me, like an invitation and a challenge. At the same time, there was incredible compassion in her eyes. I was shocked because this woman wasn’t what I was supposed to be seeing. Yet there she was, approaching very close to me, her long hair flowing, and looking at me so intensely. Finally, at the end of this practice, I went up to my teacher and said, “Does Machig Labdrön ever appear in any other forms?”

He looked at me and said, “Yes.” He didn’t say any more.

I went to bed that night and had a dream in which I was trying to get back to Swayambhu Hill in Nepal, where I’d lived as a nun, and I felt an incredible sense of urgency. I had to get back there and it wasn’t clear why; at the same time, there were all kinds of obstacles. A war was going on, and I struggled through many barriers to finally reach the hill, but the dream didn’t complete itself. I woke up still not knowing why I was trying to return.

The next night I had the same dream. It was slightly different, and the set of obstacles changed, but the urgency to get back to Swayambhu was just as strong. Then on the third night, I had the same dream again. It is really unusual to have the same dream again and again and again, and I finally realized that the dreams were trying to tell me I had to go back to Swayambhu; they were sending me a message. I spoke to my teacher about the dreams and asked, “Does this seem like maybe I should actually go there?”

He thought about it for a while; again, he simply answered, “Yes.”

I decided to return to Nepal, to Swayambhu, to find the stories of women teachers. It took several months of planning and arrangements, a key part being to seek out the biographies of the great female Buddhist teachers. I would use the trip to go back to the source and find those yogini stories and role models I so desperately needed. I went alone, leaving my children in the care of my husband and his parents. It was an emotional and difficult decision, since I had never been away from my children, but there was a deep calling within me that I had to honor and trust.

See also 7 Things I Learned About Women from Doing Yoga

Back in Nepal, I found myself walking up the very same staircase, one step after another, up the Swayambhu Hill, which I had first climbed in 1967. Now it was 1982, and I was the mother of three. When I emerged at the top, a dear friend of mine was there to greet me, Gyalwa, a monk I had known since my first visit. It was as though he was expecting me. I told him I was looking for the stories of women, and he said, “Oh, the life stories of dakinis. Okay, come back in a few days.”

And so I did. When I returned, I went into his room in the basement of the monastery, and he had a huge Tibetan book in front of him, which was the life story of Machig Labdrön, who’d founded the Chöd practice and had emerged to me as a wild, gray-haired dakini in my vision in California. What evolved out of that was research, and eventually the birth of my book Women of Wisdom, which tells my story and provides the translation of six biographies of Tibetan teachers who were embodiments of great dakinis. The book was my link to the dakinis, and it also showed me, from the tremendous response the book received, that there was a real need—a longing—for the stories of great women teachers. It was a beautiful affirmation of the need for the sacred feminine.

Learn how to step into your feminine power.

Coming Out of the Dark

During the process of writing Women of Wisdom, I had to do research on the history of the feminine in Buddhism. What I discovered was that for the first thousand years in Buddhism, there were few representations of the sacred feminine, although there were women in the Buddhist sangha (community) as nuns and lay householder devotees, and the Buddha’s wife and the stepmother who raised him had a somewhat elevated status. But there were no female buddhas and no feminine principles, and certainly no dakinis. It was not until the traditional Mahayana Buddhist teachings joined with the Tantric teachings and developed into Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism in the eighth century, that we began to see the feminine emerge with a larger role.

See also Tantra Rising

Before we continue, I want to distinguish here between neo-Tantra and more traditional Tantric Buddhism. Most people these days who see the word Tantra think about neo-Tantra, which has developed in the West as a form of sacred sexuality derived from, but deviating significantly from, traditional Buddhist or Hindu Tantra. Neo-Tantra offers a view of sexuality that contrasts with the repressive attitude toward sexuality as nonspiritual and profane.

Buddhist Tantra, also known as Vajrayana (Indestructible Vehicle), is much more complex than neo-Tantra and embedded in meditation, deity yoga, and mandalas—it is yoga with an emphasis on the necessity of a spiritual teacher and transmission. I will use the words Tantra and Vajrayana interchangeably throughout this book. Tantra uses the creative act of visualization, sound, and hand gestures (mudras) to engage our whole being in the process of meditation. It is a practice of complete engagement and embodiment of our whole being. And within Buddhist Tantra, often sexuality is used as a meta-phor for the union of wisdom and skillful means. Although sexual practice methods exist, Buddhist Tantra is a rich and complex spiritual path with a long history, whereas neo-Tantra is an extraction from traditional Tantric sexual practices with some additions that have nothing to do with it. So here when I say Tantra or Vajrayana, I am referring not to neo-Tantra but to traditional Buddhist Tantra.

Tantric Buddhism arose in India during the Pala Empire, whose kings ruled India primarily between the eighth and eleventh centuries. Remember that Buddhism had already existed for more than a thousand years by this time, so Vajrayana was a late development in the history of Buddhism. The union of Buddhism and Tantra was considered to be in many ways the crown jewel of the Pala period.

Although the origins of Buddhist Tantra are still being debated by scholars, it seems that it arose out of very ancient pre-Aryan roots represented in Shaktism and Saivism combining with Mahayana Buddhism. Though there is still scholarly debate about the origins of Vajrayana, Tibetans say it was practiced and taught by the Buddha. If we look at the Pala period, we find a situation where the Buddhist monks have been going along for more than a thousand years, and they have become very intellectually astute, developing various schools of sophisticated philosophy, Buddhist universities, and a whole culture connected to Buddhism that is very strong and alive. But at this point the monks have also become involved with politics, and have begun to own land and animals and to receive jewels and other riches as gifts from wealthy patrons. They also have become rather isolated from the lay community, living a sort of elite, intellectual, and rather exclusive existence.

The Tantric revolution—and it was a revolution in the sense that it was a major turning point—took place within that context. When the Tantric teachings joined Buddhism, we see the entrance of the lay community, people who were working in the everyday world, doing ordinary jobs and raising children. They might come from any walk of life: jewelers, farmers, shopkeepers, royalty, cobblers, blacksmiths, wood gatherers, to name a few. They worked in various kinds of occupations, including housewives. They were not monks who had isolated themselves from worldly life, and their spiritual practice reflected their experiences. There are many early tales, called the Siddha Stories, of people who lived and worked in ordinary situations, and who by turning their life experiences into a spiritual practice achieved enlightenment.

See also Tantric Breathing Practice to Merge Shiva and Shakti and Achieve Oneness

There are also some stories of enlightened women practitioners and teachers in early Buddhism. We see a blossoming of women gurus, and also the presence of female Buddhas and, of course, the dakinis. In many stories, these women taught the intellectual monks in a very direct, juicy way by uniting spirituality with sexuality; they taught based on using, rather than renouncing, the senses. Their teachings took the learned monks out of the monastery into real life with all its rawness, which is why several of the Tantric stories begin with a monk in a monastic university who has a visitation from a woman that drives him out in search of something beyond the monastic walls.

Tantric Buddhism has a genre of literature called “praise of women,” in which the virtues of women are extolled. From the Candamaharosana Tantra: “When one speaks of the virtues of women, they surpass those of all living beings. Wherever one finds tenderness or protectiveness, it is in the minds of women. They provide sustenance to friends and strangers alike. A woman who is like that is as glorious as Vajrayogini herself.”

There is no precedent for this in Buddhist literature, but in Buddhist Tantric texts, writings urge respect for women, and stories about the negative results of failing to recognize the spiritual qualities of women are present. And in fact, in Buddhist Tantra, the fourteenth root of downfall is the failure to recognize all women as the embodiment of wisdom.

In the Tantric period, there was a movement abolishing barriers to women’s participation and progress on the spiritual path, offering a vital alternative to the monastic universities and ascetic traditions. In this movement, one finds women of all castes, from queens and princesses to outcasts, artisans, winemakers, pig herders, courtesans, and housewives.

For us today, this is important as we are looking for female models of spirituality that integrate and empower women, because most of us will not pursue a monastic life, yet many of us have deep spiritual longings. Previously excluded from teaching men or holding positions of leadership, women—for whom it was even questioned whether they could reach enlightenment—were now pioneering, teaching, and assuming leadership roles, shaping and inspiring a revolutionary movement. There were no institutional barriers preventing women from excelling in this tradition. There was no religious law or priestly caste defining their participation.

See also Tap the Power of Tantra: A Sequence for Self-Trust

Dakini Symbols

Another important part of the Tantric practice is the use of symbols surrounding and being held by the deities. The first and probably most commonly associated symbol of the dakini is what’s called the trigug in Tibetan, the kartari in Sanskrit, and in English, “the hooked knife.” This is a crescent-shaped knife with a hook on the end of the blade and a handle that is ornamented with different symbols. It’s modeled from the Indian butcher’s knife and sometimes called a “chopper.” The hook on the end of the blade is called the “hook of compassion.” It’s the hook that pulls sentient beings out of the ocean of suffering. The blade cuts through self-clinging, and through the dualistic split into the great bliss. The cutting edge of the knife is representative of the cutting quality of wisdom, the wisdom that cuts through self-deception. To me it is a powerful symbol of the wise feminine, because I find that often women tend to hang on too long and not cut through what needs to be cut through. We may hang on to relationships that are unhealthy, instead of ending what needs to be ended. The hooked knife is held in the dakini’s raised right hand; she must grasp this power and be ready to strike. The blade is the shape of the crescent moon, and the time of the month associated with the dakini is ten days after the full moon, when the waning moon appears as a crescent at dawn; this is the twenty-fifth day of the lunar cycle and is called Dakini Day in the Tibetan calendar. When I come out early on those days and it is still dark, I look up and see the crescent moon; it always reminds me of the dakini’s knife.

The other thing about the dakinis is that they are dancing. So this is an expression when all bodily movements become the expression of enlightened mind. All activities express awakening. Dance is also an expression of inner ecstasy. The dakini has her right leg raised and her left leg extended. The raised right leg symbolizes absolute truth. The extended left leg rests on the ground, symbolizing the relative truth, the truth about being in the world, the conventional truth. She’s also naked, so what does that mean? She symbolizes naked awareness—the unadorned truth, free from deception. And she is standing on a corpse, which symbolizes that she has overcome self-clinging; the corpse represents the ego. She has overcome her own ego.

The dakini also wears bone jewelry, gathered from the charnel-ground bones and carved into ornaments: She wears anklets, a belt like an apron around her waist, necklaces, armbands, and bracelets. Each one of these has various meanings, but the essential meaning of all the bone ornaments is to remind us of renunciation and impermanence. She’s going beyond convention; fear of death has become an ornament to wear. We think of jewels as gold or silver or something pretty, but she’s taken that which is considered repulsive and turned it into an ornament. This is the transformation of the obstructed patterns into wisdom, taking what we fear and expressing it as an ornament.

See also Decoding Sutra 2.16: Prevent Future Pain from Manifesting

The dakinis tend to push us through blockages. They appear during challenging, crucial moments when we might be stymied in our lives; perhaps we don’t know what to do next and we are in transition. Maybe an obstacle has arisen and we can’t figure out how to get around or get through—then the dakinis will guide us. If in some way we’re stuck, the dakinis will appear and open the way, push us through; sometimes the energy needs to be forceful, and that’s when the wrathful manifestation of a dakini appears. Another important aspect of the dakini’s feminine energy is how they cut through notions of pure and impure, clean and unclean, what you should do and shouldn’t do; they break open the shell of those conventional structures into an embrace of all life in which all experience is seen as sacred.

Practicing Tibetan Buddhism more deeply, I came to realize that the dakinis are the undomesticated female energies—spiritual and erotic, ecstatic and wise, playful and profound, fierce and peaceful—that are beyond the grasp of the conceptual mind. There is a place for our whole feminine being, in all its guises, to be present.

Excerpted from Wisdom Rising: Journey into the Mandala of the Empowered Feminine by Lama Tsultrim Allione. Enliven Books, May 2018. Reprinted with permission.

About the Author

Lama Tsultrim Allione is the founder and resident teacher of Tara Mandala, a retreat center located outside of Pagosa Springs, Colorado. She is the best-selling author of Women of Wisdom and Feeding Your Demons. Recognized in Tibet as the reincarnation of a renowned eleventh-century Tibetan yogini, she is one of the only female lamas in the world today. Learn more at taramandala.org.

Excerpted from Wisdom Rising: Journey into the Mandala of the Empowered Feminine by Lama Tsultrim Allione. Enliven Books, May 2018. Reprinted with permission.

0 notes

Link

Lama Tsultrim Allione—one of the first American woman ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun— shares what she’s learned about love, life, and liberty while researching dakinis, or fierce female messengers of wisdom.

Read the stories of the Dakini—fierce female messengers of wisdom in Tibetan Buddhism to tap into your feminine power.

When I was eleven, I ran home on the last day of school and tore off my dress, literally popping the buttons off, feeling simultaneously guilty and liberated. I put on an old, torn pair of cutoff jean shorts, a white T-shirt, and blue Keds sneakers, and ran with my sister into the woods behind our old colonial New Hampshire house. We went to play in the brook burbling down the steep hill over the mossy rocks, through the evergreens and deciduous trees, the water colored rich red-brown by the tannins in the leaves of the maple trees. We would play and catch foot-long white suckerfish with our hands, and then put them back because we didn’t want to kill them.

Sometimes we swam naked at night with friends at our summerhouse in the spring-fed lake 15 miles away, surrounded by pine, birch, spruce, and maple trees. I loved the feeling of the water caressing my skin like velvet, with the moon reflecting in the mirror-like lake. My sister and my friend Joanie and I would get on our ponies bareback and urge them into the lake until they were surging up and down with water rushing over our thighs and down the backs of the horses; they were swimming with us as we laughed, clinging onto their backs.

When violent summer thunderstorms blew through, instead of staying in the old wooden house I would run and dance outside in the rain and thunder, scaring my mother. I liked to eat with my fingers, gnawing on pork chop bones and gulping down big glasses of milk, in a hurry to get back outside. I loved gnawing on bones. My mother would shake her head, saying in desperation, “Oh, darling, please, please eat with your fork! Heavens alive, I’m raising a barbarian!”

See also This 7-Pose Home Practice Harnesses the Power of Touch

Barbarian, I thought, that sounds great! I imagined women with long hair streaming out behind them, racing their horses over wide plains. I saw streaked sunrises on crisp mornings with no school, bones to gnaw on. This wildness was so much a part of me; I could never imagine living a life that didn’t allow for it.

But then I was a wife and a mother raising two young daughters, and that wild young barbarian seemed lifetimes away. Paul and I had been married for three years when we decided to move from Vashon Island back to Boulder, Colorado, and join Trungpa Rinpoche’s community. It was wonderful to be in a big, active community with many young parents. However, the strain of the early years, our inexperience, and our own individual growth led us to decide to separate and collaborate as co-parents.

In 1978, I had been a single mother for several years when I met an Italian filmmaker, Costanzo Allione, who was directing a film on the Beat poets of Naropa University. He interviewed me because I was Allen Ginsberg’s meditation instructor, and Allen, whom I had met when I was a nun in 1972, introduced me to Costanzo. In the spring of 1979, we were married in Boulder while he was finishing his film, which was called Fried Shoes Cooked Diamonds, and soon thereafter we moved to Italy. I got pregnant that summer while we were living in a trailer in an Italian campground on the ocean near Rome, and that fall we moved into a drafty summer villa in the Alban Hills near the town of Velletri.

When I was six months pregnant, my belly measured the size of a nine-months pregnant woman’s, so they did an ultrasound and discovered I was pregnant with twins. By this time I knew that my husband was a drug addict and unfaithful. I couldn’t speak the native language and felt completely isolated. In March of 1980, I gave birth to twins, Chiara and Costanzo; they were a little early, but each weighed over five pounds. I buckled down to nursing two babies, caring for my other two daughters, and dealing with my husband’s addiction, erratic mood swings, and physical abuse, which started during my pregnancy when he began to hit me.

My feelings of overwhelm and anxiety increased daily, and I began to wonder about how my life as a mother and a Western woman really connected with my Buddhist spirituality. How had things ended up like this? How had I lost that wild, independent girl and left my life as a nun, ending up in Italy with an abusive husband? It seemed that by choosing to disrobe, I had lost my path, and myself.