#rashied ali

Text

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

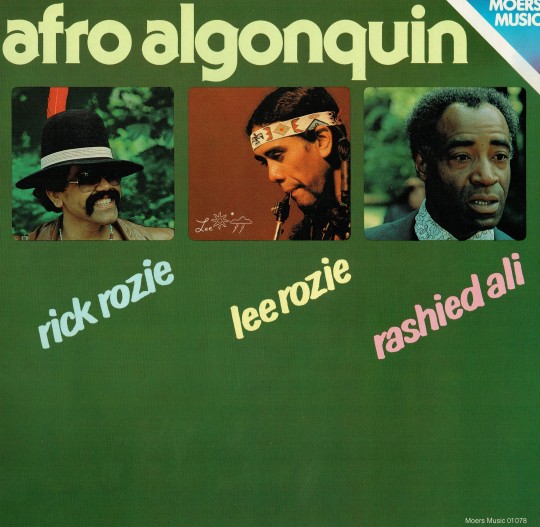

eponymous Afro Algonquin LP (1979)

#afro algonquin#retro lps#jazz#70s headbands#indigenous#1979#lee rozie#rashied ali#rick rozie#musician

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

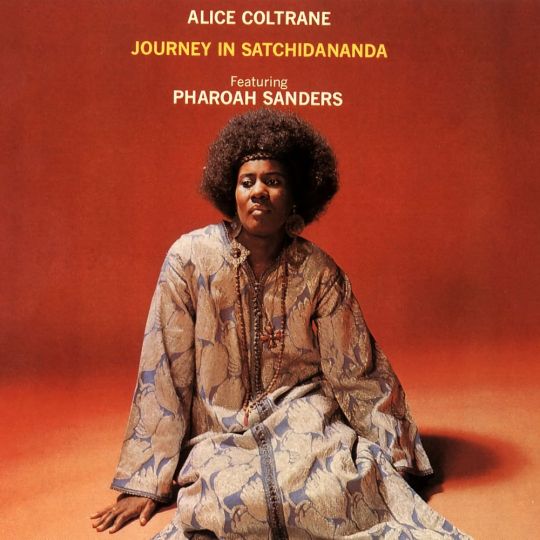

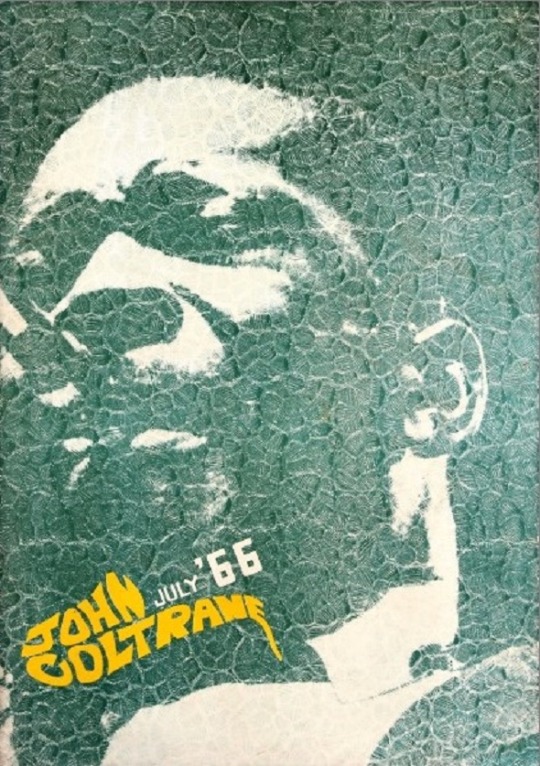

1966 - John Coltrane - Japanese concert tour program

John Coltrane (ts), Pharoah Sanders (ts), Alice Coltrane (p), Jimmy Garrison (b), Rashied Ali (dr)

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rashied Ali

#history#vintage#rashied ali#drummer#free jazz#jazz#modern jazz#modernism#avant garde jazz#black and white photography#photography#portrait#african american history#black history#black#african american#musicology#jazz histroy

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

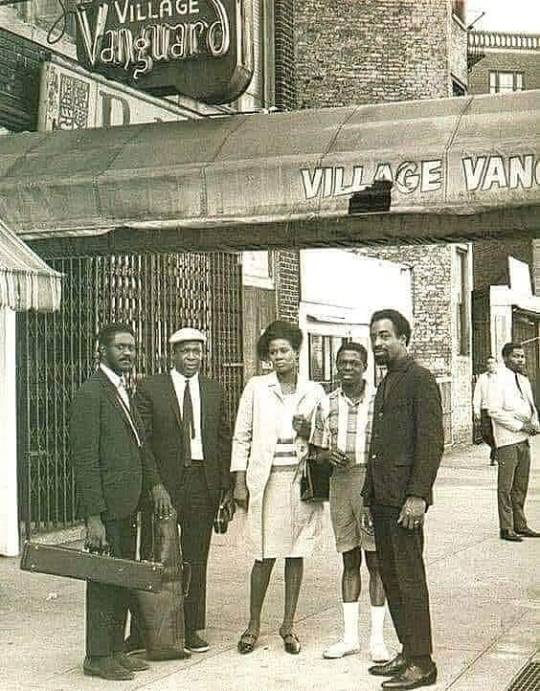

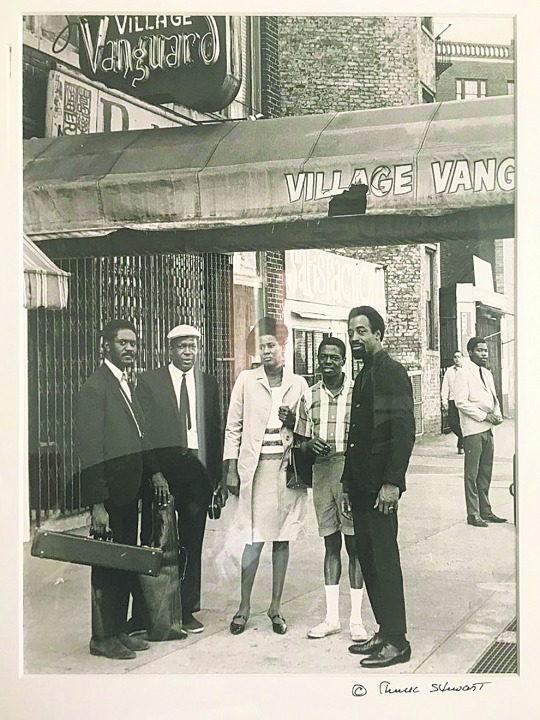

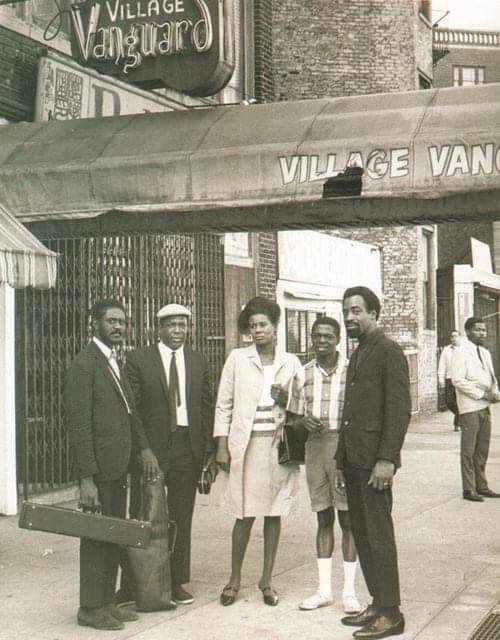

(Left to Right) Pharoah Sanders, John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane, Jimmy Garrison and Rashied Ali outside the Village Vanguard, New York, May 28, 1966. Photo cover of the album "Live at the Village Vanguard Again" 1966. Photo © Chuck Stewart

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I AM — Beyond (Division 81)

Photo by Tiffany Smith

Beyond by I AM

Interstellar Space, John Coltrane’s duet album with Rashied Ali, seems the clearest inspiration for Chicago saxophonist Isaiah Collier and drummer Michael Shekwoaga Ode. Collier says he came to Coltrane via Pharoah Sanders, and you can hear the influence of both in his tone and style. At age 23, Collier plays with a voice that feels fully formed. He is as comfortable with long lyrical phrases as the growl and shriek of the outer edges. In Ode, he has a partner who rivals Ali in both power and invention, who understands that rhythm is basic but never steady. He ranges across his kit with a lurching, stop start energy. Massive swathes of snare and cymbals here, thumping toms and kick drum here, breaking against the cliffs of traditional structure with cyclonic intensity.

Ode’s playing on “The Vessel Speaks,” for instance, is a heady concoction of battering rhythm and musicality. He matches Collier as he moves through the registers mixing glissando and overblowing with motifs that evoke New Orleans street parades and New York lofts.

On the preacher thump and yowl of “Omniscient (Mycelium),” Collier punctuates his flow with low growls of affirmation and exhortation. He pushes himself and his instrument ever further, the notes and overtones surging out as Ode crashes around his kit beneath a constant static of cymbals. On “Hymn: Love Beyond Compare,” the duo show their lyrical side. Collier breathes a prayer through his saxophone; a distant thunder rumbles as the shackles fall and the prayer ascends with a tonal clarity of tone not heard in the foregoing maelstrom. As a distillation of A Love Supreme, it would be fine, but there is a candor to the faith expressed that elevates this beyond homage.

In loosening the bounds of traditional harmonic structure, free jazz players sought transcendence, a connection to the divinity of an authentic self. Collier and Ode understand the form’s power stems from roots in the historic vernacular of field hollers, church call and response, blues narratives, and the dissonance of urbanization which flow through Black American music. So yes, Sanders, Shepp, Ayler and Coltrane inspire them, as do Graves, Murray, Elvin Jones and Ali but Beyond is the expression of Collier and Ode rather than exegesis or excavation.

Andrew Forell

#I AM#Beyond#Division 81#Andrew Forell#albumreview#dusted magazine#Isaiah Collier#Michael Shekwoaga Ode#Jimmy Chan#chicago#jazz#free jazz#john coltrane#Rashied Ali#pharoah sanders

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

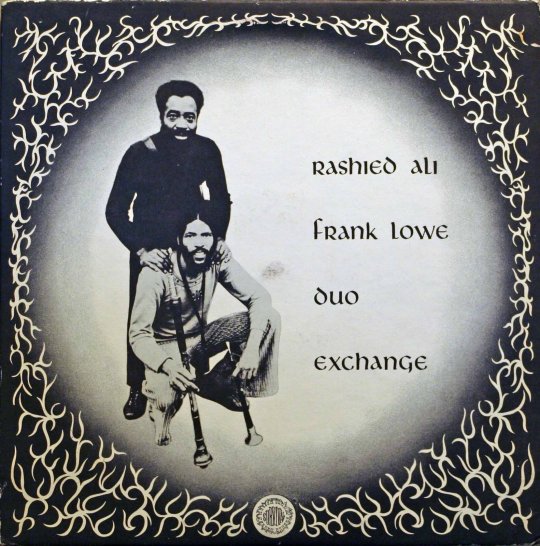

AllMusic Staff Pick:

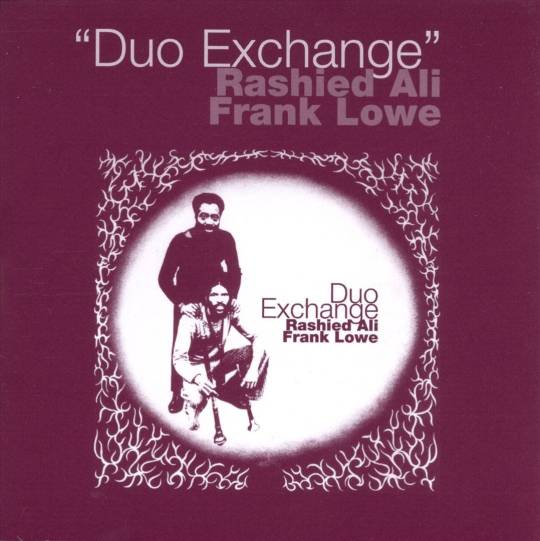

Rashied Ali

Duo Exchange

Raw, powerful, and unrelenting while remaining somehow minimal, Duo Exchange is one of the fiercest chapters of early '70s free jazz. The overdriven recording quality emphasizes the volcanic playing of both Ali and Lowe, and the interplay between drums and sax spins euphorically out of control for the entire duration of the album. An essential of free music that set the tone for punk, hardcore, noise, and other outsider avenues of expression that followed.

- Fred Thomas

0 notes

Video

youtube

Rashied Ali Quartet "Leo" live 1972

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This has long been a favorite picture of mine. It's John Coltrane's last group outside the Village Vanguard. It looks like a double exposure. There's a sort of brushstroke across the middle of it that gives it an etherial effect. With the passing in 2022 of the group's final living member, Pharoah Sanders (left), they're all ghosts now. But they come alive every time anyone, anywhere plays one of their records. (L-R Sanders, Coltrane, wife Alice, Jimmy Garrison, and Rashied Ali.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The distinctive sound of Pharoah Sanders’ tenor saxophone, which could veer from a hoarse croon to harsh multi phonic screams, startled audiences in the 1960s before acting in recent years as a kind of call to prayer for young jazz musicians seeking to steer their music in a direction defined by a search for ecstasy and transcendence.

Sanders, who has died age 81, made an impact at both ends of a long career. In 1965 he was recruited by John Coltrane, an established star of the jazz world, to help push the music forward into uncharted areas of sonic and spiritual exploration.

He had just turned 80 when he reached a new audience after being invited by Sam Shepherd, the British musician and producer working under the name Floating Points, to take the solo part on the widely praised recording of an extended composition titled Promises, a concerto in which he responded with a haunting restraint to the minimalist motifs and backgrounds devised by Shepherd for keyboards and the strings of the London Symphony Orchestra.

By then he had become a vital figure in the recent revival of “spiritual jazz”, whose young exponents took his albums as inspirational texts. When he was named a Jazz Master by the US National Endowment for the Arts in 2016, musicians of all generations, from the veteran pianist Randy Weston to the young saxophonist Kamasi Washington, queued up to pay tribute.

Farrell Sanders was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, a segregated world where his mother was a school cook, his father was a council worker and he grew up steeped in the music of the church. He studied the clarinet in school before moving on to the saxophone, playing jazz and rhythm and blues in the clubs on Little Rock’s West Ninth Street, backing such visiting stars as Bobby Bland and Junior Parker. After graduating from Scipio A Jones high school, he moved to northern California, studying art and music at Oakland Junior College. Soon he was immersing himself in the local jazz scene, where he was known as “Little Rock”.

In 1961 he arrived in New York, a more high-powered and competitive but still economically straitened environment. While undergoing the young unknown’s traditional period of scuffling for gigs, he played with the Arkestra of Sun Ra, a devoted Egyptologist. Sanders soon changed his name from Farrell to Pharoah, giving himself the sort of brand recognition enjoyed by all the self-styled Kings, Dukes, Counts and Earls of earlier jazz generations.

Amid a ferment of innovation in the new jazz avant garde, Sanders formed his own quartet. The poet LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka) was the first to take notice, writing in his column in DownBeat magazine in 1964 that Sanders was “putting it together very quickly; when he does, somebody will tell you about it”.

That somebody turned out to be Coltrane, who invited him to take part in the recording of Ascension, an unbroken 40-minute piece in which 11 musicians improvised collectively between ensemble figures handed to them at the start of the session. When it was released on the Impulse! label in 1966, critics noted that the leader, one of jazz’s biggest stars, had given himself no more solo space than any of the other, younger horn players, implicitly awarding their creative input as much value as his own.

Coltrane also invited Sanders to join his regular group, then expanding from the classic quartet format heard at its peak on the album A Love Supreme, recorded in 1964. With Alice Coltrane and Rashied Ali replacing McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones at the piano and the drums respectively, and other young musicians coming in and out as the band toured the US, the music became less of a vehicle for solo improvisation and more of a communal rite, sometimes involving the chanting of mantras and extended percussion interludes.

While some listeners were dismayed, accusing Coltrane of overdoing his generosity to young acolytes, others were exhilarated. For both camps, Sanders became a symbol of the shift. “Pharoah Sanders stole the entire performance,” the critic Ron Welburn wrote after witnessing Coltrane’s group in Philadelphia in 1966. The poet Jerry Figi reviewed a performance in Chicago and described Sanders as “the most urgent voice of the night”, his sound “a mad wind screeching through the root-cellars of Hell”. Sceptics believed Sanders was leading Coltrane down the path to perdition.

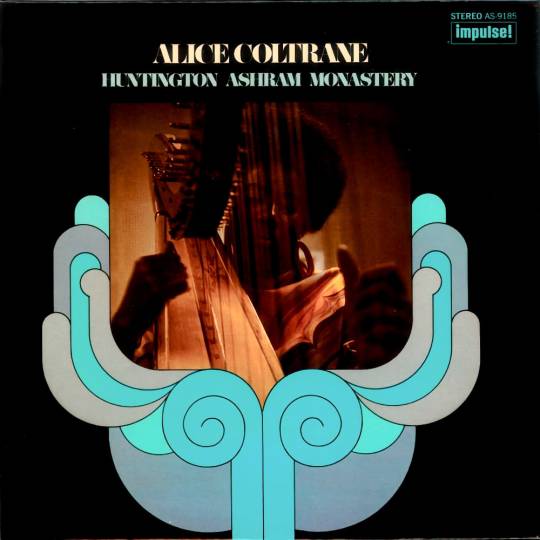

When Coltrane died of liver cancer in 1967, aged 40, Sanders began his own series of albums for Impulse!, starting with Tauhid (1967) and Karma (1969), which included an influential extended modal chant called The Creator Has a Master Plan. He continued to work with Alice Coltrane, appearing on several of her albums as well as those of Weston, Tyner, Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, Sonny Sharrock, the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra, Norman Connors and others.

In 2004 he was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame. Ten years later, he travelled from his home in Los Angeles to Little Rock, the city where his classmates had tried, in 1957, to desegregate the local whites-only high school, for an official Pharoah Sanders Day.

When asked to explain the philosophy behind the music that Baraka described as “long tissues of sounded emotion”, he replied: “I was just trying to see if I could play a pretty note, a pretty sound.” In later years, those who arrived at his concerts expecting the white-bearded figure to produce the squalls of sound that characterised Coltrane’s late period were often surprised by the gentleness with which he could enunciate a ballad. “When I’m trying to play music,” he said, “I’m telling the truth about myself.”

🔔 Pharoah (Farrell) Sanders, saxophonist and composer, born 13 October 1940; died 24 September 2022

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pharoah Sanders (13th October 1940 - 24th September 2022)

Pharoah Sanders, John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane, Jimmy Garrison and Rashied Ali outside the Village Vanguard, New York, May 28, 1966

17 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Noah Howard – Live At The Village Vanguard (1975)

00:00 Back A´Town Blues

13:15 Conversation

21:40 Dedication (To Albert Ayler)

Alto Saxophone, Tambourine, Bells – Noah Howard

Bass – Earl Freeman

Congas, Timbales – Juma Sutan

Drums – Rashied Ali

Piano – Robert Bruno

Tenor Saxophone, Bells – Frank Lowe

Written-By – Noah Howard

Recorded live at the Village Vanguard, New York City, 22nd August 1972.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Butcher & Eddie Prévost — Unearthed (Matchless)

Within improvised music, there are certain recordings that initiate timelines. One of them is John Coltrane’s Interstellar Space, which established the drums and saxophone duo as a creative situation worth exploring and documenting. The album’s name articulated the format’s appeal — maximum freedom. It provided a creative space within which the participants, freed of harmonic boundaries, were limited only by their techniques and imaginations.

Drummer / percussionist Eddie Prévost (born 1942) and soprano / tenor saxophonist John Butcher (born 1954) are members of different generations. A founding member of AMM, Prévost is part of English free improvisation’s first wave. Butcher came on the scene in the 1980s and first played with Prévost in the 1990s. They’ve had differing relationships to the format under consideration. While AMM functioned for several years as a drums / sax duo in the 1970s, Butcher steered mostly clear of drummers, as well as anything else that might push him towards a jazz-oriented way of playing, as he established his singular vocabulary of carefuly inflected, constantly non-obvious extensions of what one expects from a saxophone foror much of the 1980s and 1990s. However, they’ve developed an enduring partnership that spans several contexts, including the duo. Unearthed is their third such recording.

Unearthed is partly a creation of circumstance. The duo’s previous recordings were made in the greater London area, where Butcher lives and Prévost has often worked, and the latter employed a pared-down percussion set-up. But since it’s a bit harder for Prévost to get around these days, this recording took place in All Hallow’s Church in High Laver, Essex. The building was originally erected over 800 years ago, at which time repurposed Roman tiles and bricks were among the building materials. In addition to antiquity, it is distinguished by its active acoustic qualities. The bounce-back from old stone is not a problem for Butcher, who actively seeks to play in crypts, caverns, cisterns, and other lively acoustic situations, but an opportunity. He’s a master at incorporating the influences of echoes and absorbent surfaces into his improvisations. But while the space could easily turn an extroverted drummer’s playing into an undistinguished blare, a jazz drumkit is the instrument that Prévost has chosen to play. One of his accomplishments on this set is his deft management of the density of his playing and the clarity with which he’s been recorded. His drumming doesn’t blare, it sings, and the recording conveys both his playing and what the space does to it quite clearly.

Interstellar Space unveiled potentialities, stripping away limits to permit absolute freedom. But the human condition dictates that even if one can glimpse artistic liberty, absolute freedom is beyond anyone’s grasp. After all, Coltrane died just five months he and Rashied Ali played the session. And barriers aren’t all bad; they give a body something to push against. Prévost inhabits with the boundaries of time in several ways. He not only plays the drums with all the awareness of space, presence, and meter-transcending shape that he’s brought to AMM and so many other musical encounters; he plays them like a jazz drummer, drawing upon the brush technique, cymbal accents, metric subdivisions and syncopated pulses that a young fellow who came up playing bebop and skiffle in the 1950s learned by heart. One might say that he’s surveying his own timeline as a drummer, from back to front. There’s a moment in “Digging,” the second of the album’s long tracks, where he finishes an unaccompanied passage with a flourish that Gene Krupa would recognize as a solo-ending signal. Butcher responds with a lightly feathered, circular breathing-elongated gargle. Earlier in the same piece, he inserts echoing pops into Prévost’s spare perambulations about the snare and tom, focusing the kit’s output. The act is simultaneously contrary and completing, a reminder that one of the limits that this format shatters is the limit of one musician’s imagination.

Bill Meyer

#John Butcher#Eddie Prévost#unearthed#matchless#bill meyer#albumreview#dusted magazine#All Hallow’s Church in High Laver#free improvisation#essex

3 notes

·

View notes