#mp vol. 41 no. 3

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

#myrna loy#magazine: motion picture#year: 1931#decade: 1930s#type: studio and publicity photos#mp vol. 41 no. 3

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

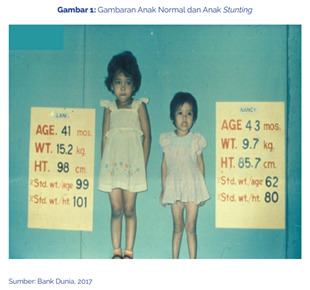

Kurang percaya diri bisa bikin anak jadi stunting?

Hai moms! Bertemu lagi dengan MPASITrend, trend ibu pintar masa kini~

Kali ini MPASITrend ingin membahas terkait masalah krusial yang kebanyakan dialami oleh ibu yang saat ini sedang memiliki baduta. Mendengar kata stunting pastinya sudah tidak asing lagi kan di telinga ibu-ibu sekalian? Atau perlu diingatkan lagi nih? Hehe. Jadi, stunting adalah masalah kurang gizi kronis yang disebabkan oleh kurangnya asupan gizi dalam waktu yang cukup lama, sehingga mengakibatkan gangguan pertumbuhan pada anak yakni tinggi badan anak lebih rendah atau pendek (kerdil) dari standar usianya. Wah, stunting cukup mengerikan juga ya! Lantas, faktor apa sih yang dapat menyebabkan anak menjadi stunting? Berikut penjelasannya:

Ada banyak faktor yang dapat menyebabkan anak menjadi stunting, baik faktor dari luar maupun dari dalam. Salah satu faktornya yaitu terkait dengan kepercayaan diri ibu (self-efficacy) dalam pemberian MPASI. Kok bisa sih kepercayaan diri menjadi salah satu faktornya? Ternyata, seorang ibu yang mempunyai kepercayaan diri baik akan memperhatikan kesiapan fisik dan psikologis anak serta kualitas atau jenis-jenis MPASI pada saat pemberian MPASI sehingga kebutuhan gizi anak dapat terpenuhi dengan baik.

Albert Bandura mendefinisikan self-efficacy sebagai keyakinan seseorang pada kemampuannya untuk berhasil melakukan tugas tertentu. Bersama dengan tujuan yang ditetapkan orang, self-efficacy adalah salah satu prediktor motivasi paling kuat tentang seberapa baik seseorang akan melakukan hampir semua upaya. Artinya, seorang ibu yang memiliki kepercayaan diri yang baik, maka akan melakukan tugasnya dengan baik juga. Dalam hal ini yaitu memberikan MPASI pada anaknya.

Namun, berbicara mengenai kepercayaan diri juga tidak semudah itu loh, harus dibarengi dengan pengetahuan yang baik juga. Karena semakin baik pengetahuan gizi ibu maka akan berdampak pada kepercayaan dirinya dalam memperhitungkan jenis dan jumlah makanan yang diperolehnya untuk dikonsumsi oleh anaknya dan tentu saja mampu menyusun menu yang baik untuk dikonsumsi oleh anaknya. Sehingga, diharapkan dengan adanya kepercayaan diri ibu serta pengetahuan yang baik, pemberian MPASI dapat dilakukan dengan tepat agar perkembangan dan pertumbuhan anaknya optimal alias tidak stunting, hehe.

Jadi, untuk ibu sekalian semangat ya! Tidak peduli latar belakang pendidikan kita apa, selagi ada usaha dan upaya untuk terus belajar, maka stunting dapat dicegah. Terlebih, di dunia yang modern ini, sangat gampang untuk mendapatkan informasi. Tapi jangan asal menyerap informasi sembarangan juga, harus tetap berdasarkan sumber terpercaya ya! Sampai jumpa di MPASITrend berikutnya moms~

Sumber Acuan:

1. Darmawan F., H., Sinta E., N., M. 2015. Hubungan Pengetahuan dan Sikap Ibu dengan Perilaku Pemberian MP-ASI yang Tepat pada BayI Usia 6-12 Bulan di Desa Sekarwangi Kabupaten Sumedang. Jurnal Bidan. 1(2): 32-41.

2. Heslin P., A., Klehe U., U. 2006. Self-Efficacy. In S. G. Rogelberg (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Industrial/Organizational Psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 705-708). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

3. Kusmiyati, Adam S., Pakaya S. 2014. Hubungan Pengetahuan, Pendidikan Dan Pekerjaan Ibu Dengan Pemberian Makanan Pendamping ASI ( MP – ASI ) Pada Bayi Di Puskesmas Bahu Kecamatan Malalayang Kota Manado. Jurnal Ilmiah Bidan. 2(2): 64-70.

4. Yusnita, Arief A., F., Athaya S., Iskandar F., R., Fitrihani P., I., Shabrina S., A. 2020. Hubungan Sikap dan Perilaku Ibu Terhadap Pemberian MP-ASI dengan Stunting pada Baduta Di Pandeglang. Seminar Nasional Riset Inovatif.

5. Tim Nasional Percepatan Penanggulangan Kemiskinan. 2017. 100 Kabupaten/Kota Prioritas untuk Intervensi Anak Kerdil (Stunting). Sekretariat Wakil Presiden Republik Indonesia: Jakarta.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital Community and Fandom: Reality TV

Reality TV has gained increasing popularity over the last 10 years and according to 2019 Roy Morgan data, it was the second most watched TV genre and viewed by 41% of Australians in an average week (Roy Morgan, 2019). In their essence, “reality TV formats are about publicizing the private” and are typically structured around ordinary people engaged in unscripted interactions, usually framed within the context of a competition or challenge (Graham & Hajru, 2011).

In March 2021, the Australia Talks National Survey collected data from 60,000 people and their viewing habits, which unearthed quite surprising results when compared to Australia’s TV ratings. Only 2 per cent of Australians said they watch reality TV more often than any other genre, which greatly contrasts data that four of the 10 top-rating shows of 2020 were reality TV. Evidently, reality TV brings about an audience paradox, which can be linked to our public perception of the genre as “junk” due to its “low production values, gossipy content and superficiality” (Watson, 2021). Furthermore, Dr Rosewarne claims that "reality TV is disproportionately consumed by women, and things that women like are usually culturally devalued,” which may further suggest why some individuals surveyed chose to fabricate their viewing habits (Watson, 2021). However, the frameworks of Reality TV have indeed shifted towards their stigmatic representation in recent times and Kavka claims that reality TV has now become “synonymous with camera-ready people (over)performing themselves in situations brimming with emotive drama, itself guaranteed by semi-scripted formats” (Kavka, 2018). Commercialisation opportunities for TV participants are now prevalent, and though Reality TV stars “used to be aggressively framed as ‘ordinary people’”, they now hold a celebrity status in society and are motivated by ‘attention capital’ (Kavka, 2018). As a result, one could argue that Reality TV has lost its status as being an unscripted form of entertainment, as producers continue to actively manipulate their participants for the best ratings.

One area of consideration for Reality TV and its contribution to public spheres is its political dimensions and potential for the creation of open discussion. A study conducted on forum spaces for ‘Big Brother’ and ‘Wife Swap’ found that the shows hosted a variety of political discussions ranging from health and the body to politicians and the government (Graham & Harju, 2011).

Graham and Harju claim that “political communication today is going through a time of decentralization” and Reality TV show politically orientated forums contribute to “the web of informal conversations that constitutes the public sphere”. In regards to Big Brother, the study found that thirty-eight threads containing 1479 postings, representing 22 percent of the initial sample, were engaged in or around political talk. Furthermore, 42 percent of these discussions dealt with issues on bullying, sexuality and gender, the role of reality TV in society and discussions on the Iraq War and performances of British MPs also emerged. Evidently, Reality TV and its tendency to focus on regular people and their behaviours has resulted in a public sphere for “talk outside the realm of traditional politics” and enables scholars to gain a better understanding of the “linkages people make between their everyday lives and society” (Graham & Harju, 2011).

Reality TV is ultimately a multi-dimensional form of media, that has come far closer to other genres in bridging the gap between audience relatability and content. Both positive and negative implications come with this style of television.

References

Graham, T., Hajru, A. (2011). Reality TV as a trigger of everyday political talk in the net-based public sphere. European Journal of Communication. Vol.28:1 pp.18-3

Kavka, M. (2018). Reality TV: Its contents and discontents. Critical Quarterly 60(4): 5-18; DOI: 10.1111/criq.12442

Roy Morgan. (2019). News and Reality TV are the most popular TV genres. [online] Roy Morgan. Available at: http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/7969-top-tv-genres-december-2018-201905060240

Watson, M. (2021). These are the shows Australians are ashamed to watch - ABC Everyday. [online] ABC Everyday. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/everyday/why-are-people-embarrassed-to-love-reality-tv/100186256

0 notes

Text

🔄 ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI - CUMI - CUMI AUDIO GLERRR !

Watch on YouTube here: 🔄 ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI - CUMI - CUMI AUDIO GLERRR !

ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI Searching for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI full album nurma kdi Om adella terbaru 2019 vol. 1 - YouTube https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:21:57 Jul 29, 2019 - Uploaded by thekurys_ MP OM ADELLA 01. Judul lagu : Tulang rusuk Vocal : nurma kdi Pencipta : Mucklas ade putra 02. Judul ... NURMA PAEJAH KDI - ADELLA LIVE ANARKIS 2019 https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 8:31 Jul 9, 2019 - Uploaded by esa production adella2019 #nurmapaejah #adellaterbaru ADELLA LIVE TEMU ... BUKAN YANG PERTAMA - NURMA ... Album koleksi Nurma kdi, Norma paejah Om Adella 2019 ... https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 32:52 3 days ago - Uploaded by Ali Sampiran Dukung channel ini dengan like, share&Subscribe ya Gaes... #NurmaKdi #Om_Adella ... Full Album Nurma Kdi Om Adella Terbaru 2019 - YouTube https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:25:56 Oct 23, 2019 - Uploaded by Musik Pro Full Album Nurma Kdi Om Adella Terbaru 2019 link : https://youtu.be/F4lc3Pp_VYw -Thank you for ... full album nurma paejah terbaru om adella vol. 2 - YouTube https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:04:38 Sep 2, 2019 - Uploaded by thekurys_ MP OM ADELLA 01. Judul lagu : Peluklah aku Vocal : nurma kdi Cipta : anton gholock 02. Judul lagu ... Non Stop ] Nurma KDI Full Album Adella Terbaru [ Dangdut ... https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:51:31 Oct 25, 2019 - Uploaded by ABR SERDADU OI Non Stop ] Nurma KDI Full Album Adella Terbaru [ Dangdut Koplo Adella Nurma KDI 2019 ... Album Om Adella terbaru 2019 yang bikin baper //nurma ... https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:41:01 Oct 13, 2019 - Uploaded by irama Coffie Album Om Adella terbaru 2019 yang bikin baper //nurma paejah KDI #adella #nurma #2019 Jangan ... Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:16:08 Aug 7, 2019 - Uploaded by thekurys_ MP OM ADELLA 01. Judul lagu : Fatamorgana Vocal : sherly kdi Pencipta : rhoma irama 02. ... full album ... ▷ Adella Full Album Norma Kdi Lagu Mp3 Song download ... https://mp3ssx.net › download › adella-full-album-norm... full album nurma kdi Om adella terbaru 2019 vol. ... Om ADELLA Live Kaliori - Rembang NORMA PAEJAH PELUKLAH AKU mp3 Duration 7:07 Size 16.29 MB ... Adella Nurma Kdi Lagu MP3 dan MP4 Video https://downloadlagu-gratis.net › download › adella-nur... Download lagu Adella Nurma Kdi (4.62 MB) dan Streaming Kumpulan Lagu Adella Nurma Kdi MP3 Terbaru Gratis dan Mudah dinikmati, ... full album nurma kdi Om adella terbaru 2019 vol 1. ... full album nurma paejah terbaru om adella vol 2. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=ALBUM%20OM%20ADELLA%20TERBARU%202019%20//NURMA%20PAEJAH%20KDI&ns0=1 https://www.pinterest.com/search/pins/?q=ALBUM+OM+ADELLA+TERBARU+2019+%2f%2fNURMA+PAEJAH+KDI https://www.webmd.com/search/search_results/default.aspx?query=ALBUM+OM+ADELLA+TERBARU+2019+%2f%2fNURMA+PAEJAH+KDI https://twitter.com/search?q=ALBUM+OM+ADELLA+TERBARU+2019+%2f%2fNURMA+PAEJAH+KDI #OmAdellaterbaru2019 #Adellaterbaru2019 #Omadellalivetejopasuruan #Omadellafullalbumterbaru2019 #Adellafullalbumterbaru2019 #OmAdella #Adella #Omadella #NURMAPAEJAHKDI Sumber https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Ou0DoGT3AE

🔄 ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI - CUMI - CUMI AUDIO GLERRR !

0 notes

Text

🔄 ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI - CUMI - CUMI AUDIO GLERRR !

Watch on YouTube here: 🔄 ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI - CUMI - CUMI AUDIO GLERRR !

ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI Searching for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI full album nurma kdi Om adella terbaru 2019 vol. 1 - YouTube https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:21:57 Jul 29, 2019 - Uploaded by thekurys_ MP OM ADELLA 01. Judul lagu : Tulang rusuk Vocal : nurma kdi Pencipta : Mucklas ade putra 02. Judul ... NURMA PAEJAH KDI - ADELLA LIVE ANARKIS 2019 https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 8:31 Jul 9, 2019 - Uploaded by esa production adella2019 #nurmapaejah #adellaterbaru ADELLA LIVE TEMU ... BUKAN YANG PERTAMA - NURMA ... Album koleksi Nurma kdi, Norma paejah Om Adella 2019 ... https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 32:52 3 days ago - Uploaded by Ali Sampiran Dukung channel ini dengan like, share&Subscribe ya Gaes... #NurmaKdi #Om_Adella ... Full Album Nurma Kdi Om Adella Terbaru 2019 - YouTube https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:25:56 Oct 23, 2019 - Uploaded by Musik Pro Full Album Nurma Kdi Om Adella Terbaru 2019 link : https://youtu.be/F4lc3Pp_VYw -Thank you for ... full album nurma paejah terbaru om adella vol. 2 - YouTube https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:04:38 Sep 2, 2019 - Uploaded by thekurys_ MP OM ADELLA 01. Judul lagu : Peluklah aku Vocal : nurma kdi Cipta : anton gholock 02. Judul lagu ... Non Stop ] Nurma KDI Full Album Adella Terbaru [ Dangdut ... https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:51:31 Oct 25, 2019 - Uploaded by ABR SERDADU OI Non Stop ] Nurma KDI Full Album Adella Terbaru [ Dangdut Koplo Adella Nurma KDI 2019 ... Album Om Adella terbaru 2019 yang bikin baper //nurma ... https://www.youtube.com › watch Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:41:01 Oct 13, 2019 - Uploaded by irama Coffie Album Om Adella terbaru 2019 yang bikin baper //nurma paejah KDI #adella #nurma #2019 Jangan ... Video for ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI▶ 1:16:08 Aug 7, 2019 - Uploaded by thekurys_ MP OM ADELLA 01. Judul lagu : Fatamorgana Vocal : sherly kdi Pencipta : rhoma irama 02. ... full album ... ▷ Adella Full Album Norma Kdi Lagu Mp3 Song download ... https://mp3ssx.net › download › adella-full-album-norm... full album nurma kdi Om adella terbaru 2019 vol. ... Om ADELLA Live Kaliori - Rembang NORMA PAEJAH PELUKLAH AKU mp3 Duration 7:07 Size 16.29 MB ... Adella Nurma Kdi Lagu MP3 dan MP4 Video https://downloadlagu-gratis.net › download › adella-nur... Download lagu Adella Nurma Kdi (4.62 MB) dan Streaming Kumpulan Lagu Adella Nurma Kdi MP3 Terbaru Gratis dan Mudah dinikmati, ... full album nurma kdi Om adella terbaru 2019 vol 1. ... full album nurma paejah terbaru om adella vol 2. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=ALBUM%20OM%20ADELLA%20TERBARU%202019%20//NURMA%20PAEJAH%20KDI&ns0=1 https://www.pinterest.com/search/pins/?q=ALBUM+OM+ADELLA+TERBARU+2019+%2f%2fNURMA+PAEJAH+KDI https://www.webmd.com/search/search_results/default.aspx?query=ALBUM+OM+ADELLA+TERBARU+2019+%2f%2fNURMA+PAEJAH+KDI https://twitter.com/search?q=ALBUM+OM+ADELLA+TERBARU+2019+%2f%2fNURMA+PAEJAH+KDI #OmAdellaterbaru2019 #Adellaterbaru2019 #Omadellalivetejopasuruan #Omadellafullalbumterbaru2019 #Adellafullalbumterbaru2019 #OmAdella #Adella #Omadella #NURMAPAEJAHKDI Sumber https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Ou0DoGT3AE

🔄 ALBUM OM ADELLA TERBARU 2019 //NURMA PAEJAH KDI - CUMI - CUMI AUDIO GLERRR ! published first on https://wesleytvirgin.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

Book Review of Manitoba Law Journal, 2018 Vol 41(4) on Criminal Law

With the release of another special issue of the Manitoba Law Journal [the Journal], it seemed appropriate to do another review. In my

review of the previous issue,

I spent some time discussing the importance of such publications, and their value to the legal field as a whole. Having made that point already, I shall not reiterate it here. Instead, with this review I would like to take a more in-depth look at the content of the present issue of the Journal. The following will provide a brief overview of each of the articles contained in volume 41(4) of the Journal, along with my own thoughts where applicable. Before diving in though, I would like once again to thank all of the individuals who worked so hard to bring this issue to publication. Their superb efforts, as always, deserve the highest praise.

The present issue of the Journalis divided into three sections. The first examines issues of terrorism, national security and transnational crime. The second looks at delay, sentencing and removal, while the third deals with disclosure, exclusion of evidence and jury instructions topics. Again, the range of topics is diverse, and all deal with issues in the legal field that are both current and significant.

The initial section was, for me, perhaps the most interesting, as it coincides with my personal interests in national and international affairs. The opening article, by Rebecca Bromwich, undertakes a critical assessment of the regulation of lawyer involvement in money laundering. Bromwich discusses the decision of the Supreme Court in Canada (AG) v Federation of Law Societies of Canada, 2015 SCC 7, which found that the Law Societies alone have the jurisdiction to regulate lawyer involvement in money laundering.1 Bromwich argues that the Supreme Court’s judgement failed to recognize the full scope of money laundering as an issue, and that the Law Societies lack the capacity to effectively regulate lawyers when it comes to money laundering. Her challenge of the self-regulation model that is so firmly entrenched in Canada is extremely interesting and thought provoking. Beyond that, I think critiques like these are important in and of themselves, because constant challenge to established systems helps us to refine them. She he raises some important points that all members of the legal profession ought to consider.

In the second article of the section, Jonathan Avey examines the tension between police independence and discipline in the Canadian military. I enjoyed this article in particular because the military realm of criminal law is one which I have seldom thought about. The military has its own parallel justice system, which is policed by its own officers, MP’s. As Avey explains, there is a dichotomy to the role of an MP: their duties encompass the work of a civilian police officer, as well as the work of a soldier supporting military operations.2 Thus, while they may act as police officers, MP’s are still subject to the chain of command, a fact which can open the door to interference in police functions by superior officers. This can also put MP’s in difficult positions, such as in R v Wellwood, 2017 CMAC 4, where an MP had to decide whether he was confident enough in his authority to act that he could disobey a direct order from a superior.3 Avey asserts that, while significant progress has been made in promoting police independence within the Canadian Forces, further changes are necessary. He suggests a series of statutory and structural changes to the military policing scheme in order to achieve this. His arguments are thoughtful and comprehensive, grounded in his experience as both a practicing lawyer and as prior member of the Canadian forces for 14 years. It also provides an interesting window into an area of the criminal law that is less commonly discussed.

The final article in this section is by Leah West, and it deals with the problem of using intelligence information, such as might be collected by CSIS, to prosecute persons returning to Canada after supporting terrorist activities abroad. This is an especially relevant topic at the moment, as the conventional defeat of the Islamic State forces has led to a dispersion of many of its foreign fighters. I have been told that one concern that governments and security experts have is that many of these individuals will now attempt to return home, bringing with them the skills that they learned in their time in the Middle East. Clearly, this represents a serious security threat to countries such as Canada. According to West, as of November 2017, 60 known foreign terrorist fighters had been allowed to return to Canada from abroad. The figure gives rise to a rather obvious question: if they are known terrorist fighters, why have they not been arrested, charged and imprisoned? The problem, illustrated by West, is that there are significant difficulties in using information collected for national security and intelligence purposes in a criminal prosecution. This is the “intelligence to evidence” problem, which West first examines, then offers some suggestions for resolving.4 West suggests that Canada look to the UK for answers, as it is a jurisdiction with far more experience in the realm of criminally prosecuting terrorists. This appears to me to be an eminently sensible suggestion: emulate those who are successful in doing what you seek to do. The issues raised by West are perhaps the most pressing contained in this issue. It will undoubtedly be difficult to balance the various interests at stake in criminal terrorist prosecutions. However, as past events have demonstrated, failing to manage the risks of terrorism can cause tragic results.

This brings us to the next section of the issue: Vulnerable Populations: Delay, Sentencing, and Removal. First up is R v Jordan: A Ticking Time Bomb, by Keara Lundrigan. This article focuses on the consequences of the Supreme Court’s well known decision in R v Jordan, 2016 SCC 27. Lundrigan asserts that Jordan is problematic in that it does nothing to incentivize more efficient prosecutions or to combat the culture of complacency that has developed towards delays and timeframes. She is also critical of the recommendation of a Senate committee to replace the remedy of a stay of proceedings with a system of costs for s 11(b) violations.5 Lundrigan argues, amongst other things, that by establishing a descriptive ceiling rather than a prescriptive one on timelines, the Court failed to incentivise decreases in delays below those ceilings, and thus did not address the underlying issue that causes delay in the first place.6 Delay is invariably one of the more complicated issues faced by the legal system, because it is bound up in the wider issue of governmental resource allocation. I found her arguments on the topic of s 11(b) remedies to be particularly persuasive. Hers is a valuable contribution to both the criminal and constitutional spheres.

The next article, by Haley Hrymak, critiques the response of British Columbia courts to the rising opioid and fentanyl crisis. It is argued that emphasising deterrence by lengthening the sentences of street level traffickers will fail to deter, increase the number of people in custody and will disproportionately impact indigenous persons and those struggling with addictions.7 These are extremely difficult issues to resolve and one on which opinions, especially among the general public, appear polarised. Hrymak’s critique is highly fact driven, making excellent and skillful use of research and numbers to support her points. It is a very well-done contribution, and worth a read, whatever one’s thoughts are on the fentanyl issue. Whether you agree or disagree with Hrymak, the facts that are presented make it clear that the present approach to dealing with this problem is not working.

The final article of the penultimate section of this issue is by Sasha Baglay, and examines how courts have considered collateral immigration impacts in sentencing, following the decision in R v Pham, 2013 SCC 15. This decision saw the Supreme Court hold that collateral immigration consequences may be taken into account during sentencing as part of the personal circumstances of the accused.8 Baglay finds that subsequent to this ruling, courts have been inconsistent in their approach to certainty of removal as a factor. The expectation was that as the likelihood of removal and severity of consequences increased, courts would be more likely to find this factor compelling.9 What was found was a large degree of inconsistency, reflecting that participants in sentencing are not particularly familiar with immigration law, and that they are still developing the requisite knowledge base.10 Baglay goes on to offer a number of suggestions on ways that this learning process can be expedited. Most salient among them, in my view, is that defence counsel needs to become better versed in immigration law. Here Baglay touches on a deeper issue that pervades the entire legal field. In an ideal world, all defence counsel would be adequately familiar with all areas of the law, as would judges and all participants in the system. Unfortunately, we do not occupy a perfect world. While I certainly agree that defence counsel ought to familiarise themselves with immigration law, as Baglay has clearly demonstrated its relevance in some cases, it is also not fair to expect counsel, (or judges) to always be familiar with every possibly relevant aspect of law. Rather, I think lawyers of all stripes need to become better at spotting potential factors that might be beyond their particular expertise, and then either bringing themselves up to speed or getting help from someone with the necessary knowledge. No one can know everything, but good counsel can recognise when they do not know something and do something about it.

We now arrive at the final section of this issue of the Journal. Opening this section is Myles Anevich with a piece on modifying disclosure in the US justice system. He argues that the favoured mode of resolution in the modern justice system is plea bargaining, not trials, and that the systemic orientation of the US justice process towards trials is out of touch with this shift in practice. In particular, disclosure obligations at the guilty plea stage are virtually non-existent. In response to this, Anevich offers three potential solutions, the last of which would be adoption of Canada’s approach to disclosure at the relevant stage of proceedings.11 I found this article to be rather fun in the respect that normally we are critiquing the Canadian system here. Let’s be honest: neither lawyers nor academics talk about what is going well. If someone is writing an article or giving a talk, or even just talking about the system with a colleague over a beer, we are all generally decrying the flaws in Canadian justice. It is important that we aim to fix what needs fixing, rather than resting on our laurels. However, it is still fun to see this reminder that there are things that (at least someone thinks) we are getting right. It is also interesting to see some American content, especially given the similarities in our countries’ approaches to law and the level to which US jurisprudence influences Canada.

Next is Heather Donkers’ article which explores the use of third-party records as a tool to challenge the credibility of sexual assault complainants. Donkers reviews the development of the law governing third-party record applications and examines a sample of cases applying the scheme to see how the judiciary has applied it, with a focus on the balancing of complainants’ privacy and equality with the full answer and defence rights of accused.12 Donkers argues that the interests and rights of complainants are under-analysed or even ignored by courts, contrary to the intent of Criminal Code s 278.5. What I found particularly disturbing about Donkers’ findings was the number of occurrences where judges appeared to ignore aspects of the prescribed legal tests entirely, sidestepping or simply not analyzing certain factors. This suggests that the core of the issue is not with the Mills decision or the black-letter law governing third-party record disclosure, but rather with the judiciary itself. Frankly, there is no reason that any judge should not consider the full range of factors, especially when the legislation provides a list. It will be interesting to see how trends develop going forward, as attitudes and norms (hopefully) change, and turnover in the judiciary continues.

The third article of the section looks at the role of police conduct in s 24(2) analyses. The author, Patrick McGuinty, argues that the first step of evidence exclusion test under s 24(2) of the Charter, which considers the seriousness of the state’s Charter infringing conduct, has become the determinative factor of the test. This is contrary to the instruction of the Supreme Court who stated, when developing the test in R v Grant, 2009 SCC 32, that all three factors are to be weighed equally.13 As part of his argument, McGuinty highlights the inconsistency with which courts have interpreted the concept of “good faith policing”, which plays a significant role in assessing police conduct under the first step. Ultimately, he argues that the lack a clear definition of good faith policing renders the great weight that the judiciary appears to put on this first step hazardous, and that this needs to be remedied so that reckless and negligent police conduct cannot be miscategorized.14 The problem that McGuinty describes is one that I have noticed myself while reading cases. There have been numerous occasions where I have read a judgement that found police to have acted in good faith, and thought to myself: the police conduct was clearly not the result of an honest mistake. As with the previous article however, I am not sure that a definition will help to remedy this when judges seem to be the problem. I worry that even with a clear definition of good faith, some judges will persist in misconstruing poor policing as good faith policing. Perhaps that is too cynical a view. Regardless, I think that McGuinty raises good points, and clarifying definitions is always a helpful step in the development of the law.

We come now to the final article of the final section of this issue of the Journal. In this piece, Lisa A Silver asserts the revolutionary nature and great importance of the decision in R v W(D), [1991] 1 SCR 742. Silver explores the impact of W(D), highlighting how it has become a fundamental principle and concept of the criminal trial. I had particular fun reading this piece due to Silver’s writing style, which makes generous use of metaphorical imagery. It is all the more fun because it does not detract from the very important points that she makes about the import of Justice Cory’s three-step jury instruction on credibility assessments.15 It is a fascinating journey that demonstrates the far-reaching impact that that a few lines in a judgement can have on the common law, depicted in a fashion to match the W(D) decision’s epic ascendance to “an invigorating principle representing the plurality of what is at stake in a criminal trial”.16 I definitely recommend reading this piece: it will give greater insight into an important aspect of the criminal trial process, and will makes obtaining that insight fun into the mix.

That brings us to the conclusion of this review ofvolume 41:4 of the Manitoba Law Journal. As before, I found myself engaged by its contents. It is interesting, relevant and packed with valuable insights into many aspects of criminal law. It contains useful, reliable information for academics or students looking for material on the covered topics, and all of the articles contained within are clear and well argued. If you are looking for a publication to read or reference, you cannot go wrong with the present issue.

Endnotes

1 Rebecca Bromwich, “(Where is) the Tipping Point for Governmental Regulation of Canadian Lawyers? Perhaps it is in Paradise: Critically Assessing Regulation of Lawyer Involvement with Money Laundering After Canada (Attorney General) v Federation of Law Societies of Canada”, (2018) 43:4 Man LJ 1 at 1.

2 Jonathan Avey, “Police Independence vs Military Discipline: Democratic Policing in the Canadian Forces”, (2018) 43:4 Man LJ 27 at 28.

3 Ibid, at 38.

4 Leah West, “The Problem of ‘Relevance’: Intelligence to Evidence Lessons from UK Terrorism Prosecutions” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 57 at 57.

5 Keara Lundrigan, “R v Jordan: A Ticking Time Bomb” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 113 at 114-115.

6 Ibid, at 122.

7 Haley Hrymak, “A Bad Deal: British Columbia’s Emphasis on Deterrence and Increasing Prison Sentences for Street-Level Fentanyl Traffickers”, (2018) Man LJ 43:4 149 at 149.

8 Sasha Baglay, “In the Aftermath of R v Pham: A Comment on Certainty of Removal and Mitigation of Sentences” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 181 at 182.

9 Ibid at 183.

10 Ibid at 215.

11 Myles Anevich, “Disclosure in the 21st Century: A comparative Analysis of Three Approaches to the Information Economy in the Guilty Plea Process” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 219 at 219.

12 Heather Donkers, “An Analysis of Third Party Record Applications Under the Mills Scheme, 2012-2017: The Right of Full Answer and Defence versus Rights to Privacy and Equality” (2018) Man LJ 245 at 245.

13 Patrick McGuinty, “Section 24(2) of the Charter, Exploring the Role of Police Conduct in the Grant Analysis” (2018) Man LJ 273 at 274.

14 Ibid at 275.

15 Lisa A Silver, “The WD Revolution” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 307 at 308.

16 Ibid at 307.

Book Review of Manitoba Law Journal, 2018 Vol 41(4) on Criminal Law published first on https://divorcelawyermumbai.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Book Review of Manitoba Law Journal, 2018 Vol 41(4) on Criminal Law

With the release of another special issue of the Manitoba Law Journal [the Journal], it seemed appropriate to do another review. In my

review of the previous issue,

I spent some time discussing the importance of such publications, and their value to the legal field as a whole. Having made that point already, I shall not reiterate it here. Instead, with this review I would like to take a more in-depth look at the content of the present issue of the Journal. The following will provide a brief overview of each of the articles contained in volume 41(4) of the Journal, along with my own thoughts where applicable. Before diving in though, I would like once again to thank all of the individuals who worked so hard to bring this issue to publication. Their superb efforts, as always, deserve the highest praise.

The present issue of the Journalis divided into three sections. The first examines issues of terrorism, national security and transnational crime. The second looks at delay, sentencing and removal, while the third deals with disclosure, exclusion of evidence and jury instructions topics. Again, the range of topics is diverse, and all deal with issues in the legal field that are both current and significant.

The initial section was, for me, perhaps the most interesting, as it coincides with my personal interests in national and international affairs. The opening article, by Rebecca Bromwich, undertakes a critical assessment of the regulation of lawyer involvement in money laundering. Bromwich discusses the decision of the Supreme Court in Canada (AG) v Federation of Law Societies of Canada, 2015 SCC 7, which found that the Law Societies alone have the jurisdiction to regulate lawyer involvement in money laundering.1 Bromwich argues that the Supreme Court’s judgement failed to recognize the full scope of money laundering as an issue, and that the Law Societies lack the capacity to effectively regulate lawyers when it comes to money laundering. Her challenge of the self-regulation model that is so firmly entrenched in Canada is extremely interesting and thought provoking. Beyond that, I think critiques like these are important in and of themselves, because constant challenge to established systems helps us to refine them. She he raises some important points that all members of the legal profession ought to consider.

In the second article of the section, Jonathan Avey examines the tension between police independence and discipline in the Canadian military. I enjoyed this article in particular because the military realm of criminal law is one which I have seldom thought about. The military has its own parallel justice system, which is policed by its own officers, MP’s. As Avey explains, there is a dichotomy to the role of an MP: their duties encompass the work of a civilian police officer, as well as the work of a soldier supporting military operations.2 Thus, while they may act as police officers, MP’s are still subject to the chain of command, a fact which can open the door to interference in police functions by superior officers. This can also put MP’s in difficult positions, such as in R v Wellwood, 2017 CMAC 4, where an MP had to decide whether he was confident enough in his authority to act that he could disobey a direct order from a superior.3 Avey asserts that, while significant progress has been made in promoting police independence within the Canadian Forces, further changes are necessary. He suggests a series of statutory and structural changes to the military policing scheme in order to achieve this. His arguments are thoughtful and comprehensive, grounded in his experience as both a practicing lawyer and as prior member of the Canadian forces for 14 years. It also provides an interesting window into an area of the criminal law that is less commonly discussed.

The final article in this section is by Leah West, and it deals with the problem of using intelligence information, such as might be collected by CSIS, to prosecute persons returning to Canada after supporting terrorist activities abroad. This is an especially relevant topic at the moment, as the conventional defeat of the Islamic State forces has led to a dispersion of many of its foreign fighters. I have been told that one concern that governments and security experts have is that many of these individuals will now attempt to return home, bringing with them the skills that they learned in their time in the Middle East. Clearly, this represents a serious security threat to countries such as Canada. According to West, as of November 2017, 60 known foreign terrorist fighters had been allowed to return to Canada from abroad. The figure gives rise to a rather obvious question: if they are known terrorist fighters, why have they not been arrested, charged and imprisoned? The problem, illustrated by West, is that there are significant difficulties in using information collected for national security and intelligence purposes in a criminal prosecution. This is the “intelligence to evidence” problem, which West first examines, then offers some suggestions for resolving.4 West suggests that Canada look to the UK for answers, as it is a jurisdiction with far more experience in the realm of criminally prosecuting terrorists. This appears to me to be an eminently sensible suggestion: emulate those who are successful in doing what you seek to do. The issues raised by West are perhaps the most pressing contained in this issue. It will undoubtedly be difficult to balance the various interests at stake in criminal terrorist prosecutions. However, as past events have demonstrated, failing to manage the risks of terrorism can cause tragic results.

This brings us to the next section of the issue: Vulnerable Populations: Delay, Sentencing, and Removal. First up is R v Jordan: A Ticking Time Bomb, by Keara Lundrigan. This article focuses on the consequences of the Supreme Court’s well known decision in R v Jordan, 2016 SCC 27. Lundrigan asserts that Jordan is problematic in that it does nothing to incentivize more efficient prosecutions or to combat the culture of complacency that has developed towards delays and timeframes. She is also critical of the recommendation of a Senate committee to replace the remedy of a stay of proceedings with a system of costs for s 11(b) violations.5 Lundrigan argues, amongst other things, that by establishing a descriptive ceiling rather than a prescriptive one on timelines, the Court failed to incentivise decreases in delays below those ceilings, and thus did not address the underlying issue that causes delay in the first place.6 Delay is invariably one of the more complicated issues faced by the legal system, because it is bound up in the wider issue of governmental resource allocation. I found her arguments on the topic of s 11(b) remedies to be particularly persuasive. Hers is a valuable contribution to both the criminal and constitutional spheres.

The next article, by Haley Hrymak, critiques the response of British Columbia courts to the rising opioid and fentanyl crisis. It is argued that emphasising deterrence by lengthening the sentences of street level traffickers will fail to deter, increase the number of people in custody and will disproportionately impact indigenous persons and those struggling with addictions.7 These are extremely difficult issues to resolve and one on which opinions, especially among the general public, appear polarised. Hrymak’s critique is highly fact driven, making excellent and skillful use of research and numbers to support her points. It is a very well-done contribution, and worth a read, whatever one’s thoughts are on the fentanyl issue. Whether you agree or disagree with Hrymak, the facts that are presented make it clear that the present approach to dealing with this problem is not working.

The final article of the penultimate section of this issue is by Sasha Baglay, and examines how courts have considered collateral immigration impacts in sentencing, following the decision in R v Pham, 2013 SCC 15. This decision saw the Supreme Court hold that collateral immigration consequences may be taken into account during sentencing as part of the personal circumstances of the accused.8 Baglay finds that subsequent to this ruling, courts have been inconsistent in their approach to certainty of removal as a factor. The expectation was that as the likelihood of removal and severity of consequences increased, courts would be more likely to find this factor compelling.9 What was found was a large degree of inconsistency, reflecting that participants in sentencing are not particularly familiar with immigration law, and that they are still developing the requisite knowledge base.10 Baglay goes on to offer a number of suggestions on ways that this learning process can be expedited. Most salient among them, in my view, is that defence counsel needs to become better versed in immigration law. Here Baglay touches on a deeper issue that pervades the entire legal field. In an ideal world, all defence counsel would be adequately familiar with all areas of the law, as would judges and all participants in the system. Unfortunately, we do not occupy a perfect world. While I certainly agree that defence counsel ought to familiarise themselves with immigration law, as Baglay has clearly demonstrated its relevance in some cases, it is also not fair to expect counsel, (or judges) to always be familiar with every possibly relevant aspect of law. Rather, I think lawyers of all stripes need to become better at spotting potential factors that might be beyond their particular expertise, and then either bringing themselves up to speed or getting help from someone with the necessary knowledge. No one can know everything, but good counsel can recognise when they do not know something and do something about it.

We now arrive at the final section of this issue of the Journal. Opening this section is Myles Anevich with a piece on modifying disclosure in the US justice system. He argues that the favoured mode of resolution in the modern justice system is plea bargaining, not trials, and that the systemic orientation of the US justice process towards trials is out of touch with this shift in practice. In particular, disclosure obligations at the guilty plea stage are virtually non-existent. In response to this, Anevich offers three potential solutions, the last of which would be adoption of Canada’s approach to disclosure at the relevant stage of proceedings.11 I found this article to be rather fun in the respect that normally we are critiquing the Canadian system here. Let’s be honest: neither lawyers nor academics talk about what is going well. If someone is writing an article or giving a talk, or even just talking about the system with a colleague over a beer, we are all generally decrying the flaws in Canadian justice. It is important that we aim to fix what needs fixing, rather than resting on our laurels. However, it is still fun to see this reminder that there are things that (at least someone thinks) we are getting right. It is also interesting to see some American content, especially given the similarities in our countries’ approaches to law and the level to which US jurisprudence influences Canada.

Next is Heather Donkers’ article which explores the use of third-party records as a tool to challenge the credibility of sexual assault complainants. Donkers reviews the development of the law governing third-party record applications and examines a sample of cases applying the scheme to see how the judiciary has applied it, with a focus on the balancing of complainants’ privacy and equality with the full answer and defence rights of accused.12 Donkers argues that the interests and rights of complainants are under-analysed or even ignored by courts, contrary to the intent of Criminal Code s 278.5. What I found particularly disturbing about Donkers’ findings was the number of occurrences where judges appeared to ignore aspects of the prescribed legal tests entirely, sidestepping or simply not analyzing certain factors. This suggests that the core of the issue is not with the Mills decision or the black-letter law governing third-party record disclosure, but rather with the judiciary itself. Frankly, there is no reason that any judge should not consider the full range of factors, especially when the legislation provides a list. It will be interesting to see how trends develop going forward, as attitudes and norms (hopefully) change, and turnover in the judiciary continues.

The third article of the section looks at the role of police conduct in s 24(2) analyses. The author, Patrick McGuinty, argues that the first step of evidence exclusion test under s 24(2) of the Charter, which considers the seriousness of the state’s Charter infringing conduct, has become the determinative factor of the test. This is contrary to the instruction of the Supreme Court who stated, when developing the test in R v Grant, 2009 SCC 32, that all three factors are to be weighed equally.13 As part of his argument, McGuinty highlights the inconsistency with which courts have interpreted the concept of “good faith policing”, which plays a significant role in assessing police conduct under the first step. Ultimately, he argues that the lack a clear definition of good faith policing renders the great weight that the judiciary appears to put on this first step hazardous, and that this needs to be remedied so that reckless and negligent police conduct cannot be miscategorized.14 The problem that McGuinty describes is one that I have noticed myself while reading cases. There have been numerous occasions where I have read a judgement that found police to have acted in good faith, and thought to myself: the police conduct was clearly not the result of an honest mistake. As with the previous article however, I am not sure that a definition will help to remedy this when judges seem to be the problem. I worry that even with a clear definition of good faith, some judges will persist in misconstruing poor policing as good faith policing. Perhaps that is too cynical a view. Regardless, I think that McGuinty raises good points, and clarifying definitions is always a helpful step in the development of the law.

We come now to the final article of the final section of this issue of the Journal. In this piece, Lisa A Silver asserts the revolutionary nature and great importance of the decision in R v W(D), [1991] 1 SCR 742. Silver explores the impact of W(D), highlighting how it has become a fundamental principle and concept of the criminal trial. I had particular fun reading this piece due to Silver’s writing style, which makes generous use of metaphorical imagery. It is all the more fun because it does not detract from the very important points that she makes about the import of Justice Cory’s three-step jury instruction on credibility assessments.15 It is a fascinating journey that demonstrates the far-reaching impact that that a few lines in a judgement can have on the common law, depicted in a fashion to match the W(D) decision’s epic ascendance to “an invigorating principle representing the plurality of what is at stake in a criminal trial”.16 I definitely recommend reading this piece: it will give greater insight into an important aspect of the criminal trial process, and will makes obtaining that insight fun into the mix.

That brings us to the conclusion of this review ofvolume 41:4 of the Manitoba Law Journal. As before, I found myself engaged by its contents. It is interesting, relevant and packed with valuable insights into many aspects of criminal law. It contains useful, reliable information for academics or students looking for material on the covered topics, and all of the articles contained within are clear and well argued. If you are looking for a publication to read or reference, you cannot go wrong with the present issue.

Endnotes

1 Rebecca Bromwich, “(Where is) the Tipping Point for Governmental Regulation of Canadian Lawyers? Perhaps it is in Paradise: Critically Assessing Regulation of Lawyer Involvement with Money Laundering After Canada (Attorney General) v Federation of Law Societies of Canada”, (2018) 43:4 Man LJ 1 at 1.

2 Jonathan Avey, “Police Independence vs Military Discipline: Democratic Policing in the Canadian Forces”, (2018) 43:4 Man LJ 27 at 28.

3 Ibid, at 38.

4 Leah West, “The Problem of ‘Relevance’: Intelligence to Evidence Lessons from UK Terrorism Prosecutions” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 57 at 57.

5 Keara Lundrigan, “R v Jordan: A Ticking Time Bomb” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 113 at 114-115.

6 Ibid, at 122.

7 Haley Hrymak, “A Bad Deal: British Columbia’s Emphasis on Deterrence and Increasing Prison Sentences for Street-Level Fentanyl Traffickers”, (2018) Man LJ 43:4 149 at 149.

8 Sasha Baglay, “In the Aftermath of R v Pham: A Comment on Certainty of Removal and Mitigation of Sentences” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 181 at 182.

9 Ibid at 183.

10 Ibid at 215.

11 Myles Anevich, “Disclosure in the 21st Century: A comparative Analysis of Three Approaches to the Information Economy in the Guilty Plea Process” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 219 at 219.

12 Heather Donkers, “An Analysis of Third Party Record Applications Under the Mills Scheme, 2012-2017: The Right of Full Answer and Defence versus Rights to Privacy and Equality” (2018) Man LJ 245 at 245.

13 Patrick McGuinty, “Section 24(2) of the Charter, Exploring the Role of Police Conduct in the Grant Analysis” (2018) Man LJ 273 at 274.

14 Ibid at 275.

15 Lisa A Silver, “The WD Revolution” (2018) Man LJ 43:4 307 at 308.

16 Ibid at 307.

Book Review of Manitoba Law Journal, 2018 Vol 41(4) on Criminal Law published first on https://medium.com/@SanAntonioAttorney

0 notes

Text

References

1. New JG (1997) The evolution of vertebrate electrosensory systems. Brain Behavior and Evolution 50: 244–252. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 2. Kalmijn A (1966) Electro-perception in sharks and rays. Nature 212: 1232–1233. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 3. Jørgensen J, Flock Å, Wersäll J (1972) The Lorenzinian ampullae of Polyodon spathula. Zeitschrift fur Mikroskopisch-Anatomische 130: 362–377. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 4. Northcutt R (1986) Electroreception in nonteleost bony fishes. In: Bullock T, Heiligenberg W, editors. Electroreception. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 257–285. 5. Northcutt R, Holmes P, Albert J (2000) Distribution and innervation of lateral line organs in the channel catfish. Journal of Comparative Neurology 421: 570–592. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 6. Northcutt R (1992) Distribution and innervation of lateral line organs in the axolotl. Journal of Comparative Neurology 325: 95–123. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 7. Scheich H, Langner G, Tidemann C, Coles R, Guppy A (1986) Electroreception and electrolocation in platypus. Nature 319: 401–402. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 8. Czech-Damal NU, Liebschner A, Miersch L, Klauer G, Hanke FD, et al. (2012) Electroreception in the Guiana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis). Proceedings of the Royal Society Biological Sciences Series B 279: 663–668. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 9. Wueringer BE (2012) Electroreception in elasmobranchs: sawfish as a case study. Brain, Behavior and Evolution 80: 97–107. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 10. Blonder B, Alevizon W (1988) Prey discrimination and electroreception in the stingray Dasyatis sabina. Copeia 1988: 33–36. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 11. Kalmijn A (1971) The electric sense of sharks and rays. Journal of Experimental Biology 55: 371–383. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 12. Lowe C, Bray R, Nelson D (1994) Feeding and associated electrical behavior of the Pacific electric ray Torpedo californica in the field. Marine Biology 120: 161–169. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 13. Haine O, Ridd P, Rowe R (2001) Range of electrosensory detection of prey by Carcharhinus melanopterus and Himantura granulata. Marine and Freshwater Research 52: 291–296. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 14. Kajiura S, Holland K (2002) Electroreception in juvenile scalloped hammerhead and sandbar sharks. Journal of Experimental Biology 205: 3609–3621. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 15. Peters R, Evers H (1985) Frequency selectivity in the ampullary system of an elasmobranch fish (Scyliorhinus canicula). Journal of Experimental Biology 118: 99–109. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 16. Sisneros J, Tricas T, Luer C (1998) Response properties and biological function of the skate electrosensory system during ontogeny. Journal of Comparative Physiology A Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology 183: 87–99. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 17. Tricas T, Michael S, Sisneros J (1995) Electrosensory optimization to conspecific phasic signals for mating. Neuroscience Letters 202: 129–132. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 18. Bratton B, Ayers J (1987) Observations on the electric discharge of two skate species (Chondrichthyes: Rajidae) and its relationship to behavior. Environmental Biology of Fishes 20: 241–254. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 19. Kalmijn A (1974) The detection of electric fields from inanimate and animate sources other than electric organs. In: Fessard A, editor. Handbook of Sensory Physiology Vol III/3. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. 147–200. 20. Kalmijn A (1978) Electric and magnetic sensory world of sharks, skates, and rays. In: Hodgson E, Mathewson R, editors. Sensory Biology of Sharks Skates, and Rays. Arlington, VA: Office of Naval Research. 507–528. 21. Paulin M (1995) Electroreception and the compass sense in sharks. Journal of Theoretical Biology 174: 325–339. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 22. Jordan LK, Mandelman JW, Kajiura SM (2011) Behavioral responses to weak electric fields and a lanthanide metal in two shark species. Journal of Experimental Biology and Ecology 409: 345–350. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 23. Kajiura SM, Holland KN (2002) Electroreception in juvenile scalloped hammerhead and sandbar sharks. journal of Experimental Biology 205: 3609–3621. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 24. Smith ED (1966) Electrical shark barrier research. Geo-marine technology 2: 10–14. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 25. Smith ED (1973) Electric anti-shark cable. Civil engineering and public works review 68: 174–176. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 26. Gilbert PW, Gilbert C (1973) Sharks and shark deterrents. Underwater Journal 5: 69–79. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 27. Smith ED (1974) Electro-physiology of the electrical shark-repellant. The Transactions of the Institute of Electrical Engineers: 166–181. 28. Smith ED (1990) A new perspective on electrical shark barriers. South African Shipping New & Fishing Industry Review: 40–41. 29. Smit CF, Peddemors VM (2003) Estimating the probability of a shark attack when using an electric repellent. South African Journal of Statistics 37: 59–78. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 30. West J (2011) Changing patterns of shark attacks in Australian waters. Marine and Freshwater Research 62: 744–754. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 31. Burgess GH, Buch RH, Carvalho F, Garner BA, Walker CJ (2010) Factors contributing to shark attacks on humans: A Volusia County, Florida, case study. In: Carrier JC, Musick JA, Heithaus MR, editors. Sharks and their relatives: II Biodiversity, adaptive physiology, and conservation. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. 32. Marcotte M, Lowe C (2008) Behavioral response of two species of sharks to pulsed, direct current electrical fields: testing a potential shark deterrent. Marine Technology Society Journal 42: 53–61. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 33. Curtis TH, Bruce BD, Cliff G, Dudley SFJ, Klimley AP, et al.. (2012) Recommendations for governmental organizations responding to incidents of white shark attacks on humans. In: Domeier ML, editor. Global Perspectives on the Biology and Life History of the Great White Shark. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. 34. Bruce BD, Stevens JD, Malcolm H (2006) Movements and swimming behaviour of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in Australian waters. Marine Biology 150: 161–172. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 35. Malcolm H, Bruce BD, Stevens J (2001) A Review of the Biology and Status of White Sharks in Australian Waters. Hobart, Tasmania: CSIRO Marine Research. 36. Bruce BD, Bradford RW (2011) The effects of berleying on the distribution and behaviour of white sharks, Carcharodon carcharias, at the Neptune Islands, South Australia. Final report to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, South Australia. Hobart, Tasmania: CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research. 37. Domeier M, Nasby-Lucas N (2007) Annual re-sightings of photographically identitifed white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) at an eastern Pacific aggregation site (Guadalupe Island, Mexico). Marine Biology 150: 977–984. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 38. Chapple TK, Jorgensen SJ, Anderson SD, Kanive PE, Klimley AP, et al. (2011) A first estimate of white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, abundance off central California. Biology Letters 7: 581–583. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 39. Anderson SD, Chapple TK, Jorgensen SJ, Klimley AP, Block BA (2011) Long-term individual identification and site fidelity of white sharks, Carcharodon carcharias, off California using dorsal fins. Marine Biology 158: 1233–1237. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 40. Fay MP (2010) Two-sided Exact Tests and Matching Confidence Intervals for Discrete Data. The R Journal 2: 53–58. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 41. Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2002) Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. New York, USA: Springer-Verlag. 488 p. 42. Massey FJ (1951) The Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Goodness of Fit. Journal of the American Statistical Association 76: 68–78. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 43. Laroche KR, Kock AA, Dill LM, Oosthouizen WH (2008) Running the gauntlet: a predator-prey game between sharks and two age classes of seals. Animal Behaviour 76: 1901–1917. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 44. Martin RA, Hammerschlag N, Collier RS, Fallows C (2005) Predatory behaviour of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) at Seal Island, South Africa. Journal of the marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 85: 1121–1135. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 45. De Vos A, O’Riain M (2010) Sharks shape the geometry of a selfish seal herd: Experimental evidence from seal decoys. Biology Letters 6: 48–50. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 46. Gubili C, Duffy C, Cliff G, Wintner S, Shivji MS, et al.. (2012) Application of Molecular Genetics for Conservation of the Great White Shark, Carcharodon carcharias, L. 1758. In: Domeier ML, editor. Global perspectives on the biology and life history of the great white shark. 47. Sepulveda CA, Graham JB, Bernal D (2007) Aerobic metabolic rates of swimming juvenile mako sharks, Isurus oxyrinchus. Marine Biology 152: 1087–1094. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 48. Robbins WD, Peddemors V, Kennelly SJ (2011) Assessment of permanent magnets and electropositive metals to reduce the line-based capture of Galapagos sharks, Carcharhinus galapagensis. Fisheries Research 109: 100–106. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 49. Brill B, Bushnell P, Smith L, Speaks C, Sundaram R, et al. (2009) The repulsive and feeding-deterrent effects of electropositive metals on juvenile sandbar sharks (Carcharhinus plumbeus). Fisheries Bulletin 107: 298–307. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 50. Rigg DP, Peverell SC, Hearndon M, Seymour JE (2009) Do elasmobranch reactions to magnetic fields in water show promise for bycatch mitigation. Marine Freshwater Research 60: 942–948. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 51. Broad A, Knott N, Turon X, Davis AR (2010) Effects of a shark repulsion device on rocky reef fishes: no shocking outcomes. Marine Ecology Progress Series 408: 295–298. View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar 52. Huveneers C, Rogers PJ, Semmens J, Beckmann C, Kock AA, et al.. (2012) Effects of the Shark Shield™ electric deterrent on the behaviour of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias). Final Report to SafeWork South Australia. SARDI Publication No. F2012/000123–1. SARDI Research Report Series No. 632. Adelaide: SARDI - Aquatic Sciences. € <1-52>http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0062730#pone.0062730-Jordan1. Effects on white shark in situ testing

0 notes

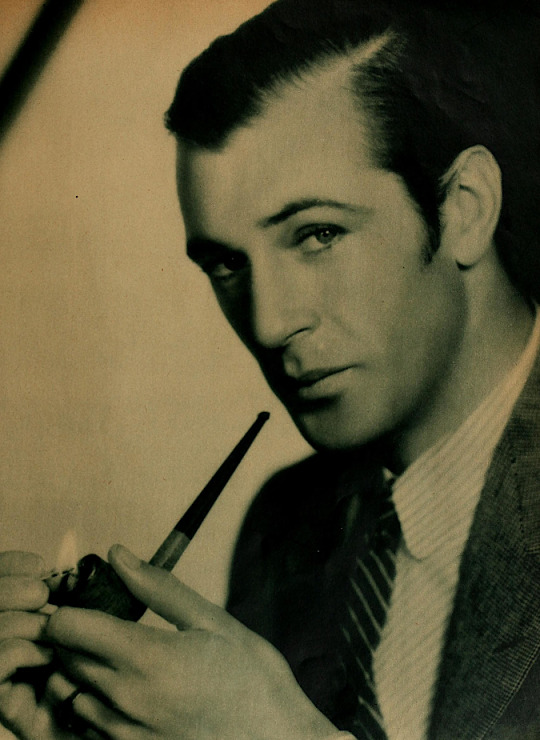

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

#gary cooper#magazine: motion picture#year: 1931#decade: 1930s#type: studio and publicity photos#mp vol. 41 no. 3

61 notes

·

View notes

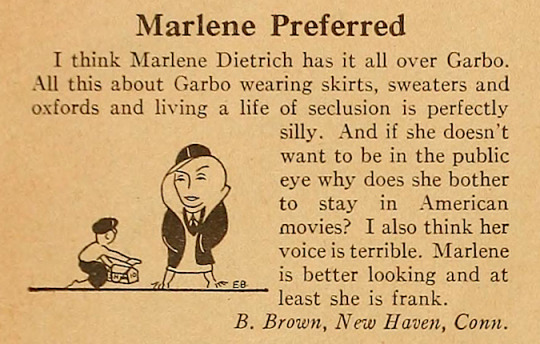

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

#marlene dietrich#greta garbo#magazine: motion picture#year: 1931#decade: 1930s#type: fan mail#mp vol. 41 no. 3

64 notes

·

View notes

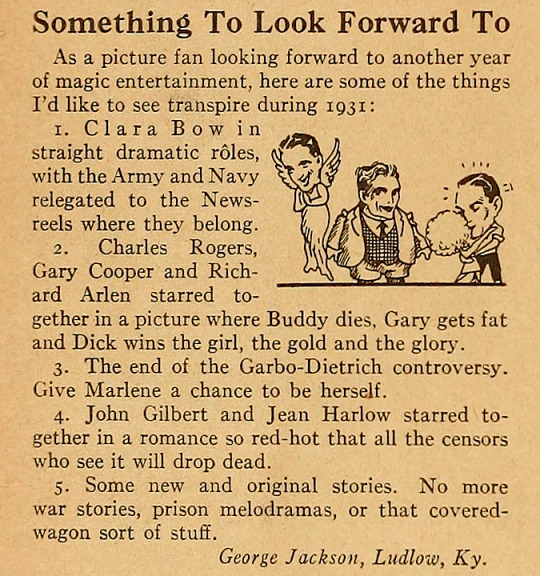

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

#clara bow#buddy rogers#gary cooper#richard arlen#greta garbo#marlene dietrich#john gilbert#jean harlow#magazine: motion picture#year: 1931#decade: 1930s#type: fan mail#mp vol. 41 no. 3

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

#marlene dietrich#greta garbo#magazine: motion picture#year: 1931#decade: 1930s#type: fan mail#mp vol. 41 no. 3

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

#john gilbert#george bancroft#victor mclaglen#conrad nagel#ronald colman#way for a sailor#magazine: motion picture#year: 1931#decade: 1930s#type: fan mail#mp vol. 41 no. 3

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

#jack oakie#adolphe menjou#greta garbo#marlene dietrich#janet gaynor#nancy carroll#clara bow#anita page#lili damita#magazine: motion picture#year: 1931#decade: 1930s#type: fan mail#mp vol. 41 no. 3

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

#jean harlow#magazine: motion picture#year: 1931#decade: 1930s#type: gossip items and anecdotes#writer: robert fender#mp vol. 41 no. 3

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Motion Picture, April 1931

20 notes

·

View notes