#marc medwin

Text

Arve Henriksen and Harmen Fraanje — Touch of Time (ECM)

youtube

What exactly is a “Redream?” Yes, it’s the third piece on trumpeter Arve Henriksen and pianist Harmen Fraanje’s new collaborative album and one of Fraanje’s own compositions, but is it a dream reboot or a contemplative revisitation of somnolence, a “regard” a la Messiaen in contemplation of the baby Jesus? Like the music on Touch of Time, that elusive title occupies a between space, a glance toward opposites that never quite solidify as expected but float by, imbued with introspective calm.

As with so many ECM albums, music and production were made for each other. Henriksen’s sound has been documented enough to need little description. Its combination of reed, flute and voice expands and obfuscates in tandem, but the breath supporting that constantly morphing timbre may never have been caught with just this level of detail in motion. It moves in physical space with the same easy grace carrying each note toward the myriad conclusions Henriksen has perfected. His inaugural phrase of “Passing on the Past” skims those shadowy lines as lush vibrato and cloudy tone bolster notes wavering through and around each other, each luffing breath a new tempo against Fraanje’s ghostly shades of motive and chord. Henriksen’s use of electronics is tasteful, as when “The Dark Light”’s melody takes on the heft of cathedral harmonies and “Mirror Images” sits anchored in a clear but deep pool of drone. In a continuation of his work on Mats Eilertsen’s And Then Comes the Night, actually recorded in the same space, Fraanje’s pianism is captured in similarly staggering detail. Every nuance of “Redream”’s pianism is front and center, and it’s as if we can watch him pedal, digging deep into each gesture as his foot teases phrases forth with rhythmic variation akin to Henriksen’s breath control. His incorporation of melodic fragments outside whatever scale the duo’s inhabiting demonstrates a masterful adventurousness, a subtly inquisitive nature tempering harmonic stasis, whispering mischievous implications at the boundaries of conventional expression.

That’s what ECM has been doing for 55 years. The label has expanded, often via methods less overt, the spaces in which being “Avant Garde” are delineated. It is spaces just like those explored by Henriksen and Fraanje that Manfred Eicher has been opening at least since Afternoon of a Georgia Faun, Marion Brown’s awe-inspiring 1970 improvised soundscape, or did the meditative universe come into being with Benny Maupin’s 1974 masterpiece The Jewel in the Lotus? Like Allan Pettersson’s approach to shifting planes of harmonic consonance and dissonance in his symphonies, those two albums defined the emotionally adjacent innovations and conventionalities the label so often explores, but ECM production offers so much more to experience. Touch of Time demonstrates yet another aspect of adherence to the label’s lineage of atmospheric sonics. Whether live or under studio conditions, foregrounded detail and room ambiance combine in a way few, if any, other labels achieve. Each creak from Fraanje’s bench or instrument and the slightest breathy movement Henriksen executes comes aliveand becomes an integral component to the music’s evolution. Each sonic document from ECM provides a coexistent narrative, telling the story of its creation even as that creation manifests, but those narratives are thorough-going. Ensembles, even a duo, morph, shedding notions of size and surrounding space even as the music eschews the confines of harmony, melody and their predispositions. Touch of Time is one of the label’s most stirring recent examples of double-narrative. Dig deeper into the electronics Henriksen employs to find worlds of undulant harmony in glorious states of becoming, and each note Fraanje plays decays with his instrument’s glorious overtones in full view. Go deeper still into each key stroke and sonic moment to find that timbre succumbs to similar flights of fancy. Are those metallic cube sounds peppering an atmosphere? Is there a ghost harmony just below a melodic surface? Did those notes external to the scale really fit perfectly after all? Re-audition tells one story, then another, and finally reiterates the first in a new way, a (re)experience well worth having.

Marc Medwin

#arve henriksen#harmen fraanje#touch of time#ecm#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#piano#trumpet#electronics#jazz

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vijay Iyer — Compassion (ECM)

youtube

The disjunct octaves don’t so much unfurl as radiate from a center of spinning molecules, masses and dotted planes gradually expanding, like a universe or a long-contained breath, elements in flux as they escape, coalesce and disperse. “Nonaah” is the perfect vehicle for the trio of Vijay Iyer, Linda May Han Oh and Tyshawn Sorey and a stunningly vibrant distillation of what sets the group, and this album, apart from so many others.

Roscoe Mitchell’s now-iconic piece is itself a flame of many colors, changing states with each varied-ensemble iteration. This version, a kind of nucleus in flux lasting a mere 2:30, reveals its secrets only as the miniature rushes toward its denouement. Each piece on this trio’s sophomore album inhabits a similar place of mystery. Watch the metric feel shift like sand under sea as “Arch” whispers, writhes and grinds, Sorey and Oh expanding and contracting the plastic pulse until duple meter and whatever its antipode might be merge and dissolve into an uneasy unity. Inhale “Prelude-Orison”’s mistily Romantic vapors, the harmonies in juxtaposition so close to cognition as to ache but, like “Nonaah”’s conjoining post-Webernian points and starkly concise warrior confrontations, refusing to conform to one type or the other.

There is no one composing with Iyer’s blend of sonority sequences, those harmonic exhortations and rebuttals that slide in and out of focus with the veteran’s complete grasp and easy grace. “It Goes” may take a pianistic page from Ellington’s slow, steady and semi-statically majestic “Reminiscing in Tempo” or the ramps and near-silent moonlit pools of Chopin’s Berceuse, but the open harmonies and melody of jagged steps and descending arpeggiated stabs are pure Iyer. Of course, the trio slides, stomps and swerves through each change and revamp with all the symbiosis a constantly performing group can muster. “Tempest”’s groove and syncopated sizzle gives Oh space for a jaw-dropping solo, augmented each time she and Iyer clamp down on that A-flat in multiple octaves, as in a Talla cycle. Sorey pushes, pulls, cajoles, confronts and rides each rhythmic rapid “Maelstrom” offers up, driving hard as the trio kicks that open modal sound to the next level. His cymbal work opening the album is nothing less than magical, and here, the hat must be doffed to ECM’s production wizardry. They capture each interplay of wire, metal and skin as Sorey swings the group along its delicate way through a brilliantly novel take on Stevie Wonder’s “Overjoyed,” itself a nod to the late lamented Chick Corea.

We learn this from Iyer’s liner notes, deserving as much attention as the music. Liners are an art form, and Iyer is one of the few performers equipped with the understated but definite poetic vision to match the weight of his convictions. His father, his musical influences and predilections as well as his global and human concerns exist in an ever-present, a moment sampled and held even as its implications shift focus. Like his compositions, his verbiage captures levels and degrees of preoccupation as they solidify around and return to a basic theme. Inspiration might be the word crystalizing it, but rereading the nearly aphoristic clauses, stretching only slightly in sentence formation, offers up so many other options. Iyer hints at philosophies while expressing a winning gratitude and humility, a nucleus through and from which past and present, his own and those influencing him, continue to evolve in prismatic celebration.

Marc Medwin

#vijay iyer#compassion#ecm#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#piano#Linda May Han Oh#tyshawn sorey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laraaji — Segue to Infinity (Numero Group)

youtube

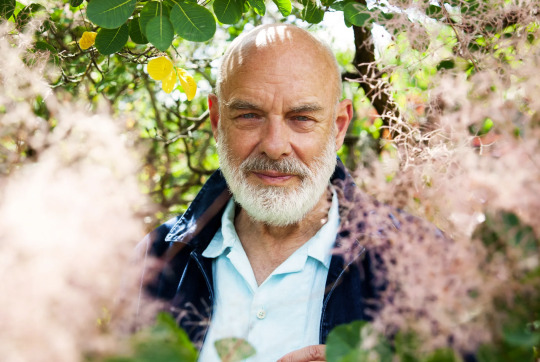

It was brass, as the artist remembered nearly four decades later, layers of brass harmony that remained somehow static, neither beginning nor ending. It was a pivotal moment for the then Edward Larry Gordon, whose middle and last names were eventually and ceremonially conflated to Laraaji. That moment of sonic vision led, with the inevitability of destiny, to the music in this 4-LP set containing some of his earliest released and recorded works.

While his most celebrated contribution is certainly his Day of Radiance album, an entry in Brian Eno’s Ambient series and produced by him, Laraaji’s discography is daunting, parts of it very difficult to track down. This set is a welcome addition to that catalog, documenting a formative phase of the instrumentalist and meditator’s journey.

As the liner notes attest, somewhere between that revelatory sound experience and these late 1970s sessions, the former comedian walked into a pawn shop and, heeding the intuitive voice he learned increasingly to trust, traded his guitar for an autoharp. Taking the bars out, he moved toward being the musician heard on that Eno collab and on his first album, Celestial Vibration, released in 1978 on the obscure SWN label and still under his birth-name. It’s the first LP in this set.

All of the trademark musical vibes pervade the two 25-minute pieces for electrified zither, peppered with effects and crackling with his trance-inducing rhythmic energy and focus. Even more wonderful is the music’s diversity as it either drives or insinuates a more sedate entity that it would be incomplete, even contradictory, to call motion. The sounds often emerge in cycles, sometimes engendered by the effects, creating a sort of rhythmically contrapuntal state that still avoids the goal-driven aesthetic associated with such conventional notions. These are overlapping and evolving cycles illuminating the path inward. The filtered resonances delineating “All-Pervading” sweep up and down the sound spectrum, invitations to partake in reflection even as the zither thrums with motoric insistence, leaving aside another more percussive sound entering a whole new harmonic area! Then, suddenly, only the complex sweep and rainbow-soft glissandi remain.

While such sounds embody and anticipate descriptors of the “New Age” genre, Laraaji’s music is far too complex for facile pigeonholing. “Bethlehem”’’s edgy opening, replete with scrapings, high-pitched rasps, rhythmic knocking and a few silences that either jar or seduce, defies all categorical felicity. Like the artist performing these vast sonic tone-paintings, the soundscape must be taken on its own terms.

The same is true for the three LPs of material only now seeing complete release. What a luxury it is to float down the titular piece’s flute-and-zither tributaries, each overtone beautifully captured as the flute traverses the stereo spectrum, gently ebbing and flowing through sound and silence until the cradling rhythms ensue. Those effect-driven eddies also permeate the bells and strings dialogue of “Koto,” placing even familiar sounds somehow beyond or just outside themselves. Tremolo, phase and vibrato carry and enhance each plucked timbre, liquifying the icy crystal transient peaks articulating their creation. The complex motions of hands or mallets on wire and wood are as faithfully rendered as the music’s raw power is both palpable and elusive.

By “Kalimba 4”’s hypnotic conclusion, during which the overtonally rich thumb piano articulations ultimately dissolve into a quietly salutary exhortation, a vast sense of completion is palpable. It is as if each of these eight excursions presents one facet of that harmonic revelation that put Laraaji on the path, each microcosmic repetition speaking to a stage in a development spiraling toward the unity at the music’s heart. This is now the most comprehensive collection of Laraaji’s work from this formative period, and the liner notes, including a wonderfully perceptive essay by Vernon Reid, give verbal voice to the celebration warranted by such a comprehensive package.

Marc Medwin

#laraaji#segue to infinity#numero group#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#box set#electric zither#flute#kalimba#new age#brian eno#new york city

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

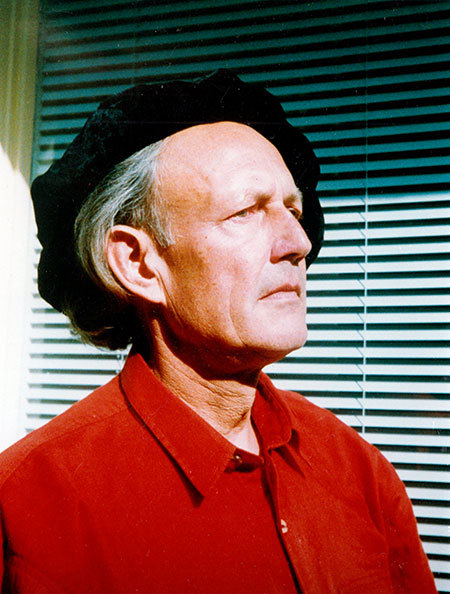

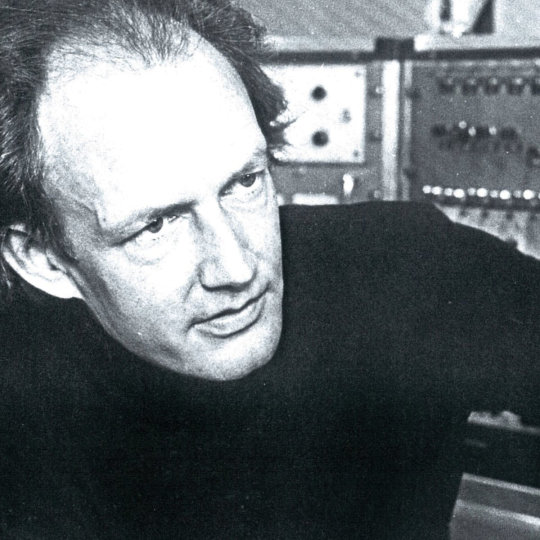

Brian Eno — FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE (UMC)

youtube

It’s only a major chord, that fundamental sonority first on the plate of every student of the Western European tradition. Luminous and warm in its somehow unfamiliar sterility, it concludes ForeverAndEverNoMore with an unambiguous moment of respite, a harnessing and dispersal of energy. The journey toward it is the point, or a series of points forming a path as lovely as it is circuitous.

This may be Eno’s most completely integrated use of sound and lyric. Yes, the album presents endlessly human concerns ranging from the environmental crisis to the ironies of self-makers and enforced labor, but there’s so much more in play, especially in the sounds themselves.

To suggest that Brian Eno is a moment-form composer would be to gild several lilies simultaneously while still addressing a pervasive musical characteristic. Sonically, these poetic soundscapes do what his recent work does but in miniature. His are neither the sequestered moments of 1960s Stockhausen nor the elastic instants of contemporaneous AMM, though he can do both when inclined. The Ship’s titular piece achieved this synthesis, while portions of Music for Airports juxtaposed them serially.

FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE is a distillation and an evolution. Like Another Day on Earth, it gathers and telescopes facets of Eno’s flirtation with the pop world, this time in a less overtly rhythmic but timbrally diverse syntax more like that on The Ship or Reflections. Take in the swirling colors fading in and out of focus as “There Were Bells” laments its way forward, birds and accordions somehow alien in the constantly ebbing and flowing tides of cognition and recognition. Recurrent and aperiodic sound-points in “Garden of Stars” contrast with the pulses inherent to “Sherry’s modified piano timbre. A second formal consideration allows that labeling the pieces as miniatures may not even constitute the best path toward considering Eno’s gemmy utterances. Like two mini-dramas in search of each other, each half of the album ends with an instrumental, the first terrifying in its cosmic import, the second somehow both blissfully alien and endlessly human, the distorted speech floating along and gently propelling the wafting harmonies.

No formal or structural conjecture addresses the album’s calmly executed and often overwhelming viscerality. The first two tracks present both micro and macrocosm in stark juxtaposition, from the one-celled organism to the blinding sky nourishing regret-tinged golden fields even as they burn. The third and fourth pieces pull eons back, into the universe’s darkest reaches and beyond, exposing star-gate and star-child in turn in seas of drone and piercing luminosity. The album’s second half finds Eno in ballad and torch-song mode, nostalgic vapor pervading each line and fragmented reminiscence. War and youth, instants of travel immortalized and cast in shiny metal float and perch atop the intimacies of pianos in Romantic harmonic exhortation. The album is full of the small noises and cosmic visions that encapsulate life, death, microbe and universe, a tick of time, like a chord, both stark and larger than itself, establishing and destroying its boundaries. This all-in-all unity gives the album astonishing power and a uniquely familiar beauty.

Marc Medwin

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Centipede—Septober Energy (Esoteric)

youtube

In June of 1971, the impossible happened, or maybe it’s just impossible now. An aggregate residing under the rather misleading, or at least incomplete, moniker “big band” converged on Wessex Sound Studios in London and recorded, under the direction of Keith Tippett and for a major label, the diverse and ultimately indescribable music comprising Septober Energy. It was to be the only album by Centipede, performing Tippett’s variously organized compositions, and it has now been reissued from the original tapes in a package that should prove as definitive as the disparately fragmenting and congealing sound-energies swirling from the speakers.

Listing the musicians would be a fruitless task; just check out the album’s Wikipedia entry for full details. Suffice it to say here that core membership from King Crimson, Soft Machine and Nucleus forms the heart of the venture, which was also produced by Robert Fripp. While he doesn’t play, Brian Godding, guitarist from Blossom Toes (whose albums have also enjoyed recent deluxe Esoteric reissues) provides still underappreciated distorted riffage, especially on the second piece. Even to cite those three groups as the orchestra’s power nexus is far from complete, as the personnel list comprises many of the finest improvisers on the English scene at the time, including Paul Rutherford, Maggie Nicols, Mongezi Feza, Dudu Pukwana, Harry Miller and so many others. Their ensemble and individual contributions fuse all manner of transcultural classical, jazz and prog influence to form the four-part epic, each piece one side of the double album.

Yes, there was a previous CD version taken from the master tapes, but there’s something richer about the sonorities here, something full, dark and sparkling by turn, presenting all instrumental and vocal details with new depth and amazing perspective. What now emerges with the most stunning clarity are the dynamic extremes. Godding’s raunchy lines blast their way onto the soundstage as wasn’t even the case with the first vinyl issue, but the album’s opening moments ring forth with crystal percussive clarity. Ditto the third part’s inaugural minutes, the vocals floating over the silence in something conjoining icy serenity and anticipation, and then those sinewy and delicious percussion dialogues, courtesy of Robert Wyatt and John Marshall, thrum, rush and roar only to fade, making room for a fusion of military and circus as exciting as it is confounding, as if Charles Ives had contributed passages to King Crimson’s Lizard. Best of all is the droning sections bookending the first piece, somehow raw and delicate, a foundation of tone transformation supporting constantly changing color and ensemble size, the initial six-minute arc anticipating the kaleidoscopic freakout and ritualistic repetitions to follow. Equally poignant are Keith Tippett’s effortless piano arpeggiations and the meditative unisons of Nicols and Julie Tippetts voices as they buoy shimmering string harmonics later in the track.

The album is a minor miracle of constantly morphing acoustic space, and this must be a consequence of Fripp’s production, which can now be appreciated afresh. Even beyond that, it cries freedom, a communal salute to a point in time when the enthusiasm underpinning such multileveled cross-reference and the projects housing it was real and immediate, perhaps less defined but inimitably palpable. If excess occasionally looms large, it is always tempered by a chamber-music veracity as the never-murky waves and rivulets ebb, flow and trickle in majestic succession. Syd Smith’s superb liner notes set the stage and spin the narrative yarn in his typically engaging and inclusive fashion. Taken as a whole, the package speaks to a time and a musical environment in which anything seemed not only to be possible but in reach, nearly tangible, the proximate dawn of another day that cycles through Julie Tippetts’ lyrics manifest. The organization gave several concerts; were any of them preserved? Either way, with the exception of Carla Bley’s monumental Escalator Over the Hill, it is difficult to think of another album encapsulating so completely the diversity in unity occurring when so many talented musicians gather in creative celebration. The fact that it is now reissued with the care it deserves is heart-warming.

Marc Medwin

#centipede#septober energy#esoteric#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#king crimson#robert fripp#soft machine

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — Sorales II (Reiger Records Reeks)

Sorales II by Roland Kayn

The deeper a dive taken into the elastic sound worlds conjured by Roland Kayn, the harder the bedrock obviously underpinning his alternately molten and frozen universe is exposed to be. Sorales II, the most recent release in the growing Kayn archive series, beggars description and confounds expectation yet again through a very surprising sort of unification.

Of course, and as always, the music is riddled with disruption. Given its 2005 vintage, that’s no surprise, and there’s plenty of what sounds like tape manipulation, that dizzying pitch shift and wrinkling effect that pervades the Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound. We are treated to the huge and all-encompassing “major chord” at 10:18, or the intriguing, because so rare, rhythmic layers that occur at least twice, the first forward and the second in reverse. They disappear with the rapidity of their genesis. Even the near silences adorning the last several minutes don’t so much disrupt as posit moments of repose in a quiet storm. The non-sequitur at 28:11 isn’t one really, and more on it presently. In those and all other cases in the 33-minute miniature, disruption is not as much of a primary ingredient. Its presence is subservient to another element, a fresh but slowly moving deep-down thing, a unity in diversity of which those New England Transcendentalists would have spoken with a mixture of pride, admiration and Classical allusion.

It seems a shame to evoke the concept of a drone in this particular instance. Yes, seasoned Kaynians will certainly recognize the long sounds that germinate, ebb and flow, often with fundamental disruptions of their own, especially throughout Kayn’s later works. This drone is different. It’s neither Vanessa Rossetto’s looping palimpsests nor Keith Rowe’s hiss, fizz and crackle conglomerations of radio static, interference, room buzz and charcoal, though it sits adjacent to both. Charles Ives would understand. His “Unanswered Question” or “Central Park In the Dark” contain string passagework that exists in similar spaces, even if the harmonic language diverges. Kayn is a Romantic, and the girders of the second Sorales prove it. Triad and elusive counterpoint emerge and merge from the cross-pollinations of tone and color that bunch, breathe, bunch again and writhe in a way that’s nearly human. Mountains and rapids form a landscape of constant motion dotted with reflective pools of moonlit tone throughout the pitch spectrum, including a single icy note approaching the stratosphere and illuminating all below. Everything is slathered in reverb, never distasteful but definite, a foundation of distant calm beneath lopsided cycles in movement. Listen closely as elements surface, half-repeat and sink. Even the disruptions, like the afore-mentioned sudden juxtaposition and the final gesture of the work, grow out of what has just occurred and out of the reverberant atmosphere containing it. It’s all cold, sometimes even windy as pitch blurs into frosty air, but it’s breathtakingly beautiful from beginning to end.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#sorales II#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#electronic#classical

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

PAKT — Live in NYC (Moonjune)

PAKT Live in NYC by PAKT - Percy Jones, Alex Skolnick, Kenny Grohowski, Tim Motzer

No one needs reminding of live music’s absence in the summer of 2020. Those days are gone, but in the middle of that uncertain season, one intrepid improvising quartet played live at Brooklyn’s Shapeshifter lab, appropriately distanced and with a very small audience. Guitarists Alex Skolnick and Tim Motzer, bassist Percy Jones and drummer Kenny Grohowski (calling themselves PAKT) found the experience so satisfying that they’ve continued collaborating, Moonjune dropping three new concert releases in July of 2023. Live in NYC is particularly special as not only did the February 18, 2023 Nublu event bring them back to New York, but the evening was organized to honor Jones, a long-time NYC resident.

Far too often, groups of high-profile players such as this one are doomed to failure before a note is played. This has nothing to do with talent, and it’s not about improvisational ability, as the same thing happens in the world of strictly composed music. An ensemble can look fantastic on paper, but playing styles and temperaments just won’t coalesce; the music suffers. PAKT improvises each performance, and while each release to date does exhibit a similar flow, it’s only the container for some extraordinary music making, which is the band’s saving grace. Yes, the NYC concert wends its way through the metric ambiguities of a requisite introduction into groove-laden collective improv but dig the dialogue! As dynamics and activity slowly build, flare and then dissipate, each moment brings interaction worthy of comparison with the most attuned improvising aggregates, regardless of genre. At around 13:50 of the first piece, just as the evening’s second groove is being set up, Jones settles on an ostinato after abandoning a few others. Grohowski grabs hold, the two lock in, and Motzer takes on the rhythmic role of a keyboard player, accenting his way into the complexities. Skolnick alternates registers, first abetting Jones and then heading upward to fill in the minuscule spaces Motzer’s left open. The whole bristles with rhythmic counterpoint that never oversaturates, but there’s plenty of melodic interplay in the mix. Listen for Jones and Skolnick’s motivic banter as the volume slowly escalates, a fray into which Motzer then jumps with alacrity.

It's difficult to articulate just why the band chemistry is so powerful. It could be about subtlety, a strange concept to be sure given the music’s vast scope and extraversion, but even the points of reference regularly evoked by each improviser address inculcation of astonishing depth. Motzer straddles the Alan Holdsworth/John McLaughlin line several minutes into the third part just before the whole band brings on some of the syncopated funk associated with Pierre Moerlen’s gong, Grohowski particularly tight as he drives and slams those moments into focus. Each player slides in and out of transtemporal monologue, as when Skolnick shifts midstream in the final stretch from a bit of Al Di Miola riffage into some blues shredding. Each note, each drum-stroke and even the occasional extramusical sounds conjure the best elements of progressive rock and psychedelia that then open doors for so many other layered associations. Finally, after all the rising and falling chaos in context, the two guitars usher the whole thing into silence with an overlapping figure as quietly poignant as it is appropriate to end what was obviously a satisfying evening for all.

Marc Medwin

#pakt#live in nyc#moonjune#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#rock#fusion#Alex Skolnick#Tim Motzer#Percy Jones#Kenny Grohowski#nublu

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — Actual Basic Elements (Reiger Records Reeks)

Actual Basic Elements by Roland Kayn

“The movie will begin in five moments,” intones Jim Morrison. It’s a pivotal moment on his American Prayer album, a public announcement amidst the often-private musings that comprise much of his poetry. Roland Kayn’s music is nothing if not cinematic, and Actual Basic Elements, a recent addition to the Kayn downloads series, brings public address into its narrative fold through extensive use of the human voice. Yet, other modes of expression occupy equal areas of sonic space as the music fragments and crystalizes, contributing to the narrative and providing the occasional plot twist.

It's the way the voice is used that differentiates Elements.” As far back as 1970s Cybernetics 3, human voices and animal sounds merged in the only slightly veiled comradery afforded by Kayn’s unique vision of acousmatic sound’s evolution. Kayn’s choice blend of action and non-action was refined over the next three decades, making this unified half-hour miniature possible. The opening conjures visions of an extraterrestrial public address system in overload, the voices buttressing the soundscape that morphs into its own soundtrack as tones emerge from vast sonic complexes. The voices hold all together, especially in the earlier parts of the reverberant score, often eclipsed but emotively clear. True to its 2005 vintage, the piece is a study in environment, expanding and shrinking in accordance with whatever processes Kayn initiated at its genesis. The Gargantuan reverberant spaces return at 5:10 and at a much higher pitch nearly four minutes later. The score, the nearest musical descriptor that makes any sense, is also rife with recurrence, as with the single pitches returning throughout at various registers. Even these can’t dispel the tape-effect disorientations also typical of the period, as at 19:07, when those dizzying luffs and waves support an only slightly oscillating tone, the whole approximating nothing so much as radio static.

Repeated listening drives the radio metaphor, yet another mode of public discourse, home with authority and conviction. Near the end of the piece, we even hear a bit of unadulterated “smooth” jazz, nearly unadorned, before it dissolves, its components demonstrated to be a major ingredient of what I insist on calling the score. That instant of musical mundanity lays bare a crucial element of what has been occurring to that point, begging other questions. Are the voices meant to simulate tape effects and the music bits of elongated radio transmissions, all layered in Protean combinations? Again, the acousmatic lies at the music’s heart, even if its purpose and execution are worlds apart from territories carved out by Kayn’s colleagues. It’s all quite delicate and elastic, vocal inflections reflecting the sonic fluidities supporting them. The only frustration is the sudden conclusion, a problem in search of resolution.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#actual basic elements#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#electronic#classical#experimental

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adrian Democ — Neha and Popínavá hudba (Another Timbre)

youtube

When the Second Viennese School composers came into their own, just at the opening of the 20th century, one way to come to terms with their innovations was to hear them in a distillation. They took the cadences and orchestral changes of Mahler or Bruckner and flushed the repeats. This trope comes to mind upon listening to this new disc of works by composer Adrian Democ. However, far from simply rehashing under a microscope, there’s much more going on in these superbly enigmatic orchestral works.

As always, the interviews on Another Timbre’s site are indispensable, both for context and for explanations of the music itself. We learn that Democ has a fair amount of experience writing for orchestral forces, but also that “Neha,” the first of the two pieces on offer here, is a Slovak word for tenderness. In this case, the constantly subdued dynamic leaves room for the ear to capture multiple levels of interaction, none more than the superimposition of chords in different temperaments that produce quiet tremblings as each sonority unfolds. This is not Vienna in distillation but Charles Ives, he of the fourth symphony, with microtones coming gorgeously to the fore. What emerges, as the near half-hour piece slides, oozes and whispers its way along a sometimes disjointed path, is a dizzying conception of size. The most minuscule intervals in what I’ll call the melody — listen to the soprano line — present vast implications as they shape the entire edifice. That reduction in size and change in import so beautifully executed by Schoenberg and the rest finds another and quite different manifestation in Democ, and the harmonies are absolutely exquisite! He describes them as simple, a bit of an overstatement given the complex orchestration and resultant timbres as each chord of varied complexity blooms and disappears, right up to the pulsed conclusion.

“Popínavá hudba” presents a host of other descriptive difficulties, which the composer goes some way toward dispelling with a rough translation involving musical representation of the climbing motion of plants. Again, dynamics inhabit a backlit world of quiet mystery as melodic line and harmonic implication merge in amoebic formations, sometimes enhancing and just as often negating each other. Microtone is also a factor, and it proves particularly effective in the surprise ending, something approaching a chorale constructed of material both familiar and new, summarizing and building upon all that has happened to that point. A muted horn might stand out, or an isolated string tone may put a temporary rip in the unified texture, but these are pieces built only around essentials. As with those proto-dodecaphonic pieces, there is a feeling of stripping away anything unnecessary, laying bare all relationships in the service of an intense listening or performative experience. To that end, the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Marián Lejava, present “Neah” with just the right blend of expansiveness and precision, while the Ostrava New Orchestra, under Petr Kotik, treat “Popínavá hudba” with similar felicity.

Marc Medwin

#adrian democ#Neha and Popínavá hudba#another timbre#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#distillations#contemporary classical#czech republic

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soft Machine — The Dutch Lesson (Cuneiform)

The Dutch Lesson by Soft Machine

Cuneiform has done it again! A more multifaceted and satisfying series of Soft Machine archival recordings is not to be found anywhere, and just when it might seem to be over, Steve Feigenbaum adds another entry into an already large catalog. The Cuneiform releases include concerts, studio and demo recordings, and while there are too many to mention, the 1967 Middle Earth Masters provides one unparalleled glimpse into early Softs as they blaze through a club set caught in surprisingly good sound. The same is true with this 1973 Rotterdam concert, and even before diving into the music, a word of praise is in order for the restoration wizardry of Ian Beabout. His recent work on Baker’s Dozen, the Muffins’ box set also on Cuneiform, set the bar very high, and The Dutch Lesson does not disappoint. The front-row taping is both vivid and extremely powerful, not to mention dynamically varied, and Beabout squeezed every last sonic detail out of it.

Those details are especially important at points of transition, as when the opening “Stanley Stamps Gibbon Album” leads first to “Between” and then into “The Soft Weed Factor.” The quartet lineup, so similar to that on the sixth album, consists of drummer John Marshall, keyboardist Mike Ratledge, winds and keys man Karl Jenkins and bassist Roy Babbington replacing Hugh Hopper. To hear the contrast between the ever-in-sync Marshall and Babbington-driven opener and the intricate and delicate “Between” is to behold a thing of rare and gentle beauty. Ratledge’s organ sound becomes more and more rounded, its distortion slowly fading into polyrhythms of delayed keyboard repetitions and luminescent percussion. Just when it seems that the sound is going to disappear altogether, so near to silence has it strayed, “Factor’s bluesy trudge emerges with perfect timing. It builds, with crushing inexorability, until Marshall and Babbington slam the groove home at 2:15. They kick into similar overdrive on a particularly maniacal rendering of “37 ½” that gives Jenkins a chance to stretch way out on what sounds like oboe. His serpentine solo eventually enters multi-phonic mode, and a more illustrative example of his improvisational chops would be difficult to imagine.

Aymeric Leroy’s notes set the stage and fill in the background, as they always do. He posits, insightfully, that the seventh album’s largely overdubbed textures probably account for the fact that only one track from it, “Down the Road,” appears in this October 1973 concert. What we do hear, an even more tantalizing proposition, is an early version of the now-iconic “Hazard Profile,” emerging headlong, with volcanic import, from “Chloe and the Pirates.” Dig the keyboard arpeggiations as Marshall’s opening roll clears a space for the track’s initial burst of groove-laden activity an astonishing 1:43 in! Yes, the drums are loud throughout, and that’s what Marshall sounds like in performance. He’s one of the most underappreciated drummers still on the scene, every power-packed roll and thud tempered by ornaments of exquisite precision and delivered with unerring timing. Again, the glacial dynamic descent leading into the following improvisation is made all the more poignant by the preceding quarter-hour of mind-stomping riff and distorto-slam.

If all you’ve heard are the album versions of these tracks, this concert will offer up a new perspective, one that hits with immediate viscerality. If the quintet lineup with Alan Holdsworth, added very soon after this concert, raised the stakes, the keys and winds so prominent in this relatively short-lived band certainly makes The Dutch Lesson well worth investigating, but there’s so much more to enjoy! We experience a band in transition as exciting as any connecting their propulsive live sets, but when has Soft Machine been anything other?

Marc Medwin

#soft marchine#the dutch lesson#cuneiform#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#prog#rotterdam#1973

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Klaus Schulze — Deus Arrakis (SPV)

youtube

It’s so easy to disappear into the billowy clouds of a Klaus Schulze soundscape, just to float away on those soft sonorities as they glide breezily by. How appropriate that the final piece on Deus Arrakis, which would turn out to be Schulze’s final album, would be called “The Breath of Life” — more on that presently — and that its fascinating timbral shifts and rhythmic layers would be the culmination of an album that seems so purposefully to anticipate its enveloping curves and contours.

Actually, the journey was first documented in 1979 with Schulze’s album Dune. Schulze’s swan song is anticipated by the single note some seven minutes into the title track as it flowers and blooms with increasingly vivid orchestral color aided by cellist Wolfgang Tiepold. Those pillows of tone in flux are only part of a stark landscape of layered rhythms and jagged atonalities, a narrative continued on “Osiris,” one of this new album’s three lengthy compositions. Its final section distills and magnifies the gorgeous effect. The rhythms have also become more subtle; they ripple from within the evolving harmonies, those Aeolian gusts that Schulze went a long way toward cultivating as far back as 1973’s iconic Cyborg. “Seth”’s seven sections update Dune’s harsher qualities even in the later and harmonically consonant sections of its circuitous progression, complemented, fittingly, by another appearance from Tiepold’s boldly beautiful cello.

If the first two pieces conjure so many shades of Schulze’s most influential work from the 1970s, even more so than does Dune, “Der Hauch Des Lebens,” to give the closer its German title, changes the game. The layered rhythms are present but even more sonically intricate, and the backdrop of harmonic wave has a crystalline vocal quality indicative of later technology. Its brew is lighter and sweeter than the richer and foamy substance at the heart of the first two pieces. This effect is offset somewhat by the evocative and slightly disturbing vocalizations of Eva-Maria Kagermann. She introduces a breathy humanity to the ethereal chords and rhythms as they swim, stagnate and are revitalized. Rhythm becomes increasingly fragmented, ricocheting around the soundstage before being subsumed.

The album’s overall effect is one of transcendent synthesis. It is an obvious temptation, though appropriate in this case, to suggest a summation on Schulze’s part. Thematically and musically, he absorbs and reabsorbs the listener in slow builds and burning crescendos both Romantic and starkly modern in turn. The subtle repetitions concluding the album’s finale are completely engrossing and moving. Best of all though, the final section embodies the spirit of ascent as the harmonies and timbres rise in a kind of jubilant acceptance, a conclusion of immense optimism still grounded in the minor mode. The album would signify a triumphant return to form under any circumstances, but its success is doubled as a valedictory statement, a vision long-nourished but still in flux and now representing a pioneering voice silenced.

Marc Medwin

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nick Storring — Music from 'Wéi 成 (Orange Milk)

Music from Wéi 成为 by Nick Storring

What mysteries can imbue five ascending dyads! Composer and multi-instrumentalist Nick Storring demonstrates the phenomenon six and a half minutes into the second part of his Music From 'Wéi 成, but that delicate moment is only one in a kaleidoscopic entrenchment of tones, colors and sustains that codify and unify this latest project from the imaginative and prolific Toronto-based musician.

Storring has one of those rare compositional voices that combines consonance and dissonance in a way that elucidates narrative rather than relationship. That musical moment just mentioned tells the story. Something approaching a major foundation, or at least it has major inflections, buoys those crystalline ascents that eschew while never quite shattering the serenity. More remarkable than all of that, all sounds in this project emanate from a single source. This is an album of piano music, but it lives in that space carved out most vigorously over the past decade or so by those treating the piano as the totality it always has been. Edgard Varese wanted to forget about the antiquated instrument, but Storring, like other sympathetic minds, exploits every one of its many sonic characteristics. Uniquely though, his is a dense but surprisingly calm world of simultaneities. Over several years, he crafted music to accompany a dance project, recording in various locations and on various pianos, ultimately offering a multileveled aural experience as diverse but as consistent as the family of instruments he employed.

It happens way too often, but where mere verbiage is concerned, moments must suffice until the trip is taken. Dive in anywhere! If rhythmic intrigue is the order of the day, dig into the quasi-funky breaks opening the penultimate section. It’s got some Reichian phase but magnified, as if those 18 musicians were told to step up the pace and spread out! If reflection comes closer to the desired effect, the fourth section’s initial and overlapping pointillisms and arpeggios should fill the bill. The clumsy word repetition doesn’t even begin to describe what occurs as this music drifts forward, planting seeds of harmony and counterpoint only to abandon them in favor of high-register grindings and industrial scufflings, and then the distant screech and cicada whirrings of stroked wire as mode and chord are supplanted by their polar opposites. Bass harmonics and mid-level sustains flesh out the sparse but ironically full texture as the music inhabits neither one world nor the other, form and structure in constant but felicitous erosion until those arpeggios return in a different register.

Enough of moments! This is a continuous work that should be experienced just that way. Unlike so many other projects, it isn’t just that the piano’s sound worlds are emphasized. All manner of morphage and manipulation detaches element from element, a decay from an attack, a sustain from the velvety hammer blow birthing it. These miniscule considerations are disassembled to be reconfigured, layered and set stark against a dynamic background in constant and orchestral flux. Admirers of the piano’s traditional languages will revel in their spacious appearances, while those in search of the more radical need only wait until the next transition. The album’s beauty is forced to roar in and out of focus as often as it reflects. The music itself brims with the fluid energy of rapid-fire discovery still maintaining time to breathe. Through it all runs the obvious and infectious joy of creation, spontaneity and considered craft in gloriously recorded tandem.

Marc Medwin

#nick storring#Music from 'Wéi 成#orange milk#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#composition#piano#dyads#toronto

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Path of Silence — Ancestral Light (Synphaera)

Ancestral Light by Path of Silence

Vladimir Sokolović's second album as Path of Silence is really kind of a debut. His earlier effort was a compilation of material assembled over a decade, while Ancestral Light presents as a unified statement, one in which the artist’s voice is both readily identifiable and deepened by experience and history, allowing each moment additional and layered poignancy.

As with so many ambient artists, Sokolović favors the chordal sustain and sonic wash augmented by modular blocks of rhythm and pitch in repetition, at least partially indebted to those of Klaus Schulze that gives his label its name. Sokolović’s earlier material employed these in abundance and was peppered with the looped and reversed sounds of what might be called sci-fi. They are still present but sonically deepened, and the music has been expanded while also stripped to essentials. “Dismantle the Hologram”’s nearly ten minutes comprise a prime example of the combination of furthest reaches and in-your-head microdetails that define this soundworld. At a fundamental level, we get a C-major chord. It ebbs and flows with an airy certainty that thickens and thins out again as it progresses, beginning in a low register and expanding outward, finally engulfing all else in a blaze of glorious multi-registral sound near the conclusion. In tandem, ratchets and crystalline showers pervade, counterpointing modular motives harkening back to those 1970s glory days, the whole a wonderful technological palimpsest, a feast for the ears! The single harmony gains in upper-structural intrigue as it transmogrifies, gaining something approaching a second tonality near the end. As for the timbre of that startlingly lush complex, could be strings, could be voices in celestial chorus, who knows? It hardly matters and fragments follow fragments, bits and bobs of harmony transmute into their melodic components and then back again, and the whole swims in a sea of glacial development at once tranquilly static and replete with motion.

This seductive relationship, as melody becomes harmony and vice versa, is maintained throughout the album, especially on the ambiguous “Remains.” Rhythms are often generated from inside the melodies themselves, Tangerine Dream style, as on the staccato “Gates Between Worlds.” That phrase could describe the whole project, as it’s a gorgeous and often nearly subliminal journey through points of something never reaching stasis but hovering around it, and it will be fascinating to hear where the next leg of that journey takes this creative musician.

Marc Medwin

#path of silence#ancestral light#Synphaera#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#Vladimir Sokolovic#ambient#electronic

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening Post: Wadada Leo Smith

Regular Dusted readers probably require no preamble or primer when it comes to Wadada Leo Smith. A stalwart leader, innovator and educator in creative improvised music across six decades, Smith ascended to octogenarian status on December 18th of last year. The Finnish TUM imprint prefaced that momentous occasion with a series of physical releases organized around instrumentation and collaboration, with colleagues both longstanding and comparatively recent to Smith’s voluminous sound world.

Four were released in 2021, including the solo Trumpet, Sacred Ceremonies teaming Smith in duos and trio with Milford Graves and Bill Laswell, The Chicago Symphonies composed for his Great Lakes Quartet, and A Sonnet for Billie Holiday with Vijay Iyer and Jack DeJohnette. Production delays prevented the release of the final two entries until June 2022. Emerald Duets engages Smith in diverse dialogues with a revolving roster of drummers that includes DeJohnette, Andrew Cyrille, Han Bennink, and Pheeroan akLaff. String Quartets Nos. 1-12 delves deeply into an under-documented side of his oeuvre in featuring pieces for two string ensembles and a small cadre of guest soloists.

In sum, it’s a massive and magisterial amount of material, gorgeously recorded and lovingly presented. A fitting tribute to Smith at this milestone of his life and work and a noble case of “giving him his flowers while he’s still with us.” Dusted writers participating in this Listening Post were understandably daunted the prospect of digesting and discussing so much music. Smith’s sustained artistry and imagination were instant agents in assuaging and even allaying such fears. In the interests of expediency and economy our ensuing conversation focuses on the final two sets in TUM’s series, starting with Emerald Duets.

Intro by Derek Taylor

Derek Taylor: Precedence was on my mind a lot when listening to these discs. Trumpet and drums still aren’t a common combination. As far as I know, the first recorded example dates to Roy Eldridge and Alvin Stoller, who recorded a trio of duets while waiting for other players to show up at a Benny Carter studio session on March 21st, 1955. A fourth track featured Eldridge on overdubbed piano. They still sound striking today in their vibrant collisions of melody and rhythm. Smith’s most certainly intimately familiar with them.

youtube

Of the six releases in the 80th Birthday series, Emerald Duets and Trumpet feel the most allegiant to and resonant with the arc of Smith’s career from start to present. Percussion in the tradition of the AACM’s “little instruments” has been part of his personal palette from the beginning, featuring prominently in his solo Kabell projects from 1972 and 1979. Dialogues with drummers were a natural progression. There are a handful of recordings in that format that predate this set and show off Smith’s predilection for picking partners ready to go all in on the conversations. I’m really curious to learn what others have gleaned from many highlights of these meetings.

Bill Meyer: Duos in general, and duos with percussionists in particular, are an important facet of Smith’s work. While some recent efforts, such as Ten Freedom Summers, use larger ensembles to make grand artistic statements, the duos can be very personal encounters; personally, I find their intimacy very appealing. I remember reading somewhere that Smith said he thinks it is important to break bread with a duo partner, even when their dietary habits are very different than his. At the time, he was talking about Anthony Braxton. Of all the times I’ve seen Smith perform, the one that affected me most was a duo concert with the German percussionist, Günter Baby Sommer. They have decades of rapport, and it showed in the ways they supported each other making really poetic, beautiful statements. Besides Sommer, the drummers he has previously recorded duets with include Ed Blackwell, Adam Rudolph, Jack DeJohnette, Milford Graves, Sabu Toyozumi and Louis Moholo-Moholo. Emerald Duets enlarges that number by three. He’s worked in many other settings with Andrew Cyrille and Pheeroan akLaff; I’m not informed about Smith's history with Han Bennink. John Corbett did an interview with Smith in 2015 for Bomb magazine where Smith mentions seeing Bennink play, but I don’t know if he’s ever played with him before.

Marc Medwin: If he has worked with Bennink before, I've not heard of it either. I heard about the food symbiosis from him directly, and yes, relating to Braxton, about 15 years ago. Performative intimacy has long been paramount to Smith, as we hear as far back as the Creative Construction Company material and the Kabell Years retrospective. What fascinates me is that, like Bill Dixon, even when Smith works in duo, his take on that intimacy can be quite malleable. The sound can be large, sometimes monumentally so. Maybe it's something about the space and dynamic range in his playing, or maybe it's simply the way the instrumentalists react and interact in the environment Smith has created via the score. Just as a point of comparison, on Coltrane's Interstellar Space, I do not hear that huge sense of physical space as

much as lines in intersection. Each piece on The Emerald Duets sounds very spacious to me, in a physical sense.

Michael Rosenstein: This series celebrating his 80th birthday has been a treasure trove of interesting work. What's particularly interesting about this batch of duos with drummers is how they draw on musicians he's had a longstanding association with. I can't find specific documentation but it seems likely that Smith and Jack DeJohnette crossed paths in Chicago in the 1960s as part of their activities with AACM if not at the Creative Music Studio in Woodstock, NY in the 1970s. Smith's 1970s collaborations with Pheeroan ak Laff are better documented including a set from Studio Rivbea as part of the Wildflower series and as part of and early New Dalta Ahkri lineup from New Haven. I'm not sure if Smith and Bennink ever played together, but they were both part of Derek Bailey's Company 6 and Company 7 recordings from 1977 so they were at least traveling in the same circles. The earliest documentation I can find of his collaborations with Andrew Cyrille are from the late 1990s playing in a group assembled by John Lindberg. But it seems like their paths might have crossed earlier in New York.

That's a lot of collective experience in this set!

Bill Meyer: DeJohnette moved to NY from Chicago in 1966, and Smith came to Chicago after being in the army in January 1967. But it’s fair to suppose that Smith knew of him from the 1960s on, given DeJohnette’s involvement with Miles Davis as well as his Chicago roots. George Lewis mentions in his AACM study, A Power Stronger Than Itself, that DeJohnette was a frequent presence at Creative Music Studio.

youtube

Derek Taylor: Smith and Sommer have an excellent disc on Intakt, Wisdom in Time, from 2006 and the trio they shared with Peter Kowald from a quarter-century earlier is one of the touchstones of the FMP catalog. So much rapport and mutual listening on display, as Bill notes, and congruous willingness to go pretty much anywhere with the music. It’s a common thread in Smith’s work and I love the “food symbiosis” descriptor as a synopsis of the intentional cultivation of differences-intact cause and effect.

Among these duets, I had the greatest anticipation for the session with Bennink. I’m not aware of any earlier recordings of the two outside the Company disc that Michael mentions and Bennink’s singular brand of intensity, levity and piebald swing feels like a novel foil for Smith. It doesn’t disappoint in that regard. Smith’s penchant for verbose dedicatory titles is in florid bloom and there’s a fascinating emphasis on naming individuals and locales across time and space. Familiar figures (Louis Armstrong, Ornette Coleman, Albert Einstein) are named alongside others (Dorothy Vaughn, Mary Jackson) that had me referencing Google. The open dynamics that Marc notes are on full display with Bennink reigning in his more extravagant impulses. It's like an extended meditation with strong, sharp teeth occasionally bared.

youtube

Bill Meyer: Derek, your point about the titles that Smith gives to the music draws attention to one of the things that I think Smith has in common with Braxton or Dixon: he doesn’t just want to play, he wants to put out a lot of information. The immensity is part of the point. In Smith’s case, this involves spiritual, cultural, sensate, social, scientific and aesthetic concerns. But this can coexist with an attention to tonal and gestural detail; the music asks you to think both big and small. At its best, the music does both, and so far, I find that in the encounter with DeJohnette, where there’s an evident, cooperative give and take between the players, and also titles that reference rarified experiences and interdisciplinary inquiry.

I say so far because I’ve only listened to the duos once or twice each, and I think that the choice to package several full sessions in a box corresponds to a request to consider this music’s messages for a while now, and also for a long time afterwards. One spin is just getting started. On my first listen, the duo with Bennink sounds like two skilled musicians having some fun playing together.

Derek Taylor: Bill, I like your observation about immensity as intentionality and the comparison to output of Braxton and Dixon. The latter’s Odyssey set (five discs of mostly solo trumpet and flugelhorn and a sixth with spoken exegesis of the same) is a spiritual precursor to Smith’s Trumpet and a similarly deep, transportive dive. That kind of fecundity runs the risk of feeling like listener homework when engaged beyond a sampling, but I think Smith largely sidesteps the issue in the breadth and allure of these sets. Even with the economy of instrumentation on Emerald Duets, there’s a wealth of variety and interplay that’s consistently satisfying.

DeJohnette gets the most time with Smith over two complete sessions and I agree, there’s a very productive workshop feel to their encounters that goes well beyond that of a casual conclave. One of the dates is also set apart in that both men double on pianos (acoustic and electric). These are the discs I’ve spent the least time with so far, but that’s primarily because of a desire for repeat visits to the Bennink and Cyrille sessions.

Getting back to meaning-rich titles, the Cyrille has a canny mix of dedicatory pieces and refreshingly political ones. Jeanne Lee, Donald Ayler and Mongezi Feza get the shoutouts and “The Patriot Act, Unconstitutional Force that Destroys Democracy” (a piece also interpreted on the first DeJohnette session) leaves no equivocation as to Smith’s political and humanist sensibilities. Gratifying to see local Representative Ilhan Omar garner a piece on the Cyrille session. It makes me wonder if she’s heard it, and if not, invites the temptation to drop a copy off at her office in downtown Minneapolis.

Jennifer Kelly: I know a lot less about Smith than most of you, though once, on a trip to Chicago, I met up with Bill Meyer at the University of Chicago to see him play and accept some kind of award? (Bill do you remember the details?) It was an incredible evening, very warm and welcoming. I remember one of his grandchildren running around, and everyone very tolerant of that, kind of a family vibe. I think I had already heard a little bit of his work, maybe Ten Freedom Summers?

vimeo

In any case, I am also enjoying the drummer duets and finding that I really like Smith's trumpet tone, which is full of air and seems softer and less piercing than other players. It's very ruminative and evocative to my ears. We've been talking about him primarily as a composer, which, fair enough...but what do we think about him as a performer and interpreter of his music?

I've also been dipping into the string quartets and wanted to draw your attention to a piece in the New York Times, which talks about his unusual notation ...one of the reasons that this material is not performed very often.

The difference between his drummer duets and these very lush, romantic classical string is really striking. What do you guys see as the common thread?

Derek Taylor: Jenny, I agree about the inviting nature of Smith’s brass tone(s). There’s clarity and elasticity to it across time that’s extraordinary. He can play harsh and discordant with a mastery of wide array of extended techniques. Although more often there’s a sonorousness suffusing his phrases that’s disarming, but also direct. He found his instrumental voice early and has shaped it to so many different settings to the degree that he’s pretty easy to single out, no matter the ensemble size. A similar singularity informs his architectures for strings, which I was initially surprised by, but then realized I probably shouldn’t have been.

Separating Smith’s composing and playing is difficult for me. There seems to be so much overlap and interaction between the two disciplines. That’s true of many improvising musicians, but it feels particularly so with Smith. The Duets are an excellent example of this intersectionality with each drummer confidently bringing their individual tool kits to bear on the cues and structures, which don’t just encourage, but entreat such interplay.

Probably an unfair and perhaps unanswerable question, but is there a drumming partner amongst the four that resonates most with folks?

Bill Meyer: Jen, I think we saw him play in October 2015 with a version of the Golden Quartet, with (iirc) Anthony Davis on piano, John Lindberg on bass, and Mike Reed on drums. I don’t recall an award, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. That concert stood out to me because I felt like Smith was kind of playfully messing with Davis and Lindberg. Most times, Smith has a kind of esteemed elder air about him. They were playing some of his graphic scores, and I particularly remember Davis seeming a bit flummoxed.

Smith has incorporated elements of classical instrumentation and forms for decades; on the Spirit Catcher album, which was recorded c. 1979, he performs with a harp trio, and on Ten Freedom Summers, the four-disc work that was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 2013, the music switched between the Golden Quartet, a ten-piece chamber ensemble, and a merger of the two. I haven’t dipped too far into the string quartets yet, but in general I really value the presence of Smith as a player in his music. His trumpet brings things into focus for me.

youtube

Marc Medwin: I love the description of the quartets as Romantic! In a very fundamental way, they are, not that they sound like Mahler or Tchaikovsky. I'm listening to the 9th quartet as I type, and harmony's this wonderfully open and malleable thing, certainly not atonal! The more I think about it, I hear the duets as pretty Romantic as well, and I mean that in the sense of size, as we've been discussing, and in the sense of fluidity as one event melds with another, forms and spaces in which boundaries aren't so much transgressed as disappear. Smith's trumpet tones can sound like that. One pitch can take on many

shades and even…what, characters?

Christian Carey: The duets are so captivating. Without a harmony instrument (except the few places when piano is introduced, which I particularly liked), it is up to Wadada Leo Smith to fill in the implications of harmony with single trumpet lines, which he does with a keen sense of progression. That said, the duets are primarily about Smith's soaring melodic style and the sharing of rhythmic ideas between him and the various drummers.

There is a bridging of the gap between duet partners. Smith plays differently with each of the drummers, acknowledging their musicality. All of the drummers bridge the gap as well, doing a fine job of arriving in Smith's orbit. I was particularly struck by how Smith and Han Bennink met in the middle, with the drummer discarding some of his more manic incursions to truly inhabit Smith's compositions.

Bill Meyer: Yeah, Bennink eschews both the antic side of his late free approach and his pre-bebop swinging brushes approach. He meets Wadada where he’s at and just plays.

So far, my favorite duets are the ones with DeJohnette. I think they share an inclination to compose in real time, which leads to their music having an especially patient, thoughtful quality.

Smith’s notation system is called Ankhrasmation. Here’s an interview that includes some discussion of it. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/wadada-leo-smith/

Derek Taylor: Smith elucidates influences on his string quartet writing in the set’s accompanying book, starting with Ornette’s Town Hall 1965 piece “Dedication to Poets and Writers” and moving through the works of Bartok, Beethoven, Debussy, Webern and Shostakovich. Alongside a broad list of African American composers from Scott Joplin to Alvin Singleton, he weaves in B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and John Lee Hooker. Smith also parcels his compositions into four temporal periods. The dozen pieces documented in the box comprise three of these periods, with a fourth consisting of three more compositions as yet unrecorded corresponding to 13th, 14th, and 15th Constitutional Amendments ratified during the Lincoln Presidency.

In Smith’s words: “My aspiration was to create a body of music that is expressive and that also explores the African American experience in the United States of America. My music is not a historical account. I intend that my inspiration seeks a psychological and cultural reality.”

He continues, “I therefore construct a music that relies on non-traditional components and concepts that allows a shared responsibility for the horizontal flow of the music, including the creative ability to reshape recurrences of musical moments both with interpretations and expressions, to introduce new and different languages into a single work and use that language as a form of expansion and not as a development.”

Lots to unpack and ponder there, and titles once again become dedicatory guideposts in signifying inspiration. The four movements of the first quartet correspond to four African American composers. The two movements of the ninth are named after Ma Rainey and Marian Anderson, respectively. The first movement of the twelfth is for Billie Holliday.

The guests that join the Redkoral Quartet on four of the 12 pieces obviously break with the conventions of the string quartet format. Christian, given your experience as a composer and theorist, I’m curious how you see Smith aligning with and diverging from the lineage of this instrumentation.

Just a side note on the presentation of these sets. As with the earlier releases in the series, the physical packaging and contents of theses final two entries are superlative. The price point is steep, but TUM spared no expense in covering the curatorial and annotative bases. It’s all appealing, from color photographs and reproductions of accompanying artwork to detailed and diverse essays and a sturdy, handsome cardboard exterior. Even interior sleeves within sleeves for the discs. As a collective 80th birthday present to an American treasure, it’s a homerun.

youtube

Justin Cober-Lake: Catching up after a few days away, I hope I don't derail things by looping back. I'm most interested in his duets with Pheeroan akLaff, mainly because America’s National Parks was my entry into serious consideration of Smith's work. akLaff told me at the time that there's an "ethos connecting the player and the score.” Listening to these duet combinations in parallel (especially given the recurrence of "The Patriot Act" allows for some thinking on that topic. How does a player connect to these complex scores, and how does that change among players? How do a pair of artists connect to each other over the same score in different ways. akLaff's work on "The Patriot Act" is my favorite of the batch, but maybe only because I feel a certain resonance there. DeJohnette seems to have more freedom; while he certainly has more time, I may be reading into the collaborative nature of that performance. I'd be curious to learn more about the process. In this case, how does Smith — who composed the piece — adjust his playing to his duet partner? Does he have something different in mind ahead of time, knowing who he's playing with (he knows these artists well) or is approach more reactive?

Derek Taylor: Thanks for linking to your piece, Justin. Even more grist to chew on. The duets feel different from Smith’s ensemble pieces to me on several fronts. Most obviously, they’re dialogues, so the material is geared towards dyadic interplay interlaced with solo expression. Something cellist Ashley Walters notes in your piece seems germane to the differences, too: “Wadada’s music is not completely fixed nor completely free: it lies somewhere in the middle where parts can slide across each other or align depending on the performance. In this way, performing with [his] ensemble is the ultimate chamber music experience: you know each part so well that you can react and create music with each other in real time.”

Each of these drummers is a deft and experienced improviser. Smith recognizes and relies on that throughout, according ample latitude to their decisions and contributions. Bennink’s a great example of that trust placed paying off in an unexpected way. Certain of his more idiosyncratic percussive trademarks are left absent in the service of preserving the tenor and poise of Smith’s compositions. It’s still identifiably Bennink behind the kit, but magnanimously attenuated to Smith and vice versa.

Justin Cober-Lake: The idea of magnanimity remains crucial to Smith's work, in various ways. His titles, his inspirations, and his culture statements make that clear in one way, but his way of interacting with his collaborators always seems to be one of clear conversation and generosity. He has very specific ideas in his compositions, but even those lend themselves toward further communication, between him and other artists and between the artists and the audience. Ankhrasmation and graphic scores are complex, academic concepts, but they're also languages that let people speak to each other in new ways while encouraging a certain amount of improvisation (Watlers' point is certainly relevant). His partners have to study this language, and part of the fun is recognizing what new sorts of ideas come out of conversation within a new discourse community. Listening to the duets lets us see that paired down to its most essential qualities.

This may point to a separate rabbit trail not worth following, but I tend to think of him working on a grand scale, taking on ideas like the national park system or the Civil Rights Movement, and the duets seem to me to be a distillation of how he works. Another way to approach them would be to start with his solo pieces (like the Monk album) and see how he builds into something with a duo, trio, strings, etc. Or maybe the solo work is just totally different, more of him as a player and less as a composer.

Marc Medwin: I would venture that the solo work, or rather I should say his solo work in particular, straddles the lines you draw. The solo set in the birthday series, Trumpet, contains compositions that also speak to all of the issues, political or otherwise, that have formed the substance of our discussion. I am drawn again and again to the inculcation of a moment's implications in Smith's work, which all of us have been mentioning in one way or another, whether in recording or performance.

There is something of the elder's wisdom in what Smith says or plays, a distillation of the spiritual and cultural continua that we often separate for convenience, and he brings similar modes of thinking and construction out of his collaborators. I find the idea of chamber music being such a huge part of the music we're discussing so close to my own thinking! He loves the term "Research," to which he refers quite a lot when discussing his work, and as those who've spent any time with him or read his interviews know, he can bring in wildly disparate notions of science, art, literature and politics at a moment's notice but somehow unify the entire discussion around a concept, opening up terminological meaning beyond expectation. So, I keep thinking, what is chamber music anyway?! What is a symphony, a string quartet, and who gets to delineate those boundaries?

Derek Taylor: Marc, I really like this passage of yours, “there is something of the elder’s wisdom in what Smith says or plays, a distillation of the spiritual and cultural continua that we often separate for convenience, and he brings similar modes of thinking and construction out of his collaborators.”

It’s an assignation that could be applied to a number of Smith’s peers. I’m thinking Henry Threadgill, Roscoe Mitchell, Braxton… even William Parker to a degree. Although magical realism and extrasensory erudition as often informs Parker’s cross-cultural cosmology isn’t really an emphasis in Smith’s perspective. Smith seems more interested in existence and reality as shaped by and expressed in tangible historical manifestations. His themes and cues transcend temporal boundaries, but they’re still grounded in factual people, places, events, etc. although not limited to those. They’re also tools in deconstructing and reconstructing or replacing established and hierarchical terminology and ideas. Chamber music in Smith’s conception feels much more inclusive and holistic than the Western classical definition, for example.

The String Quartets are customary string quartets in the sense that the members of the RedKoral Quartet play instruments associated with the conventions and traditions of that format, but how they play them and the soloists that occasionally join them resist and redefine that codification.

Marc Medwin: Yes! Threadgill and Mitchell exhibit a similarly inclusive historical bent, though you're spot on regarding Smith's spirituality, a layered tradition he takes very seriously. With Mitchell, we have transmogrifications like the semi-autobiography of Bells for the South Side, while Threadgill transfigures creative music's history with a degree of earthiness that Smith tends to eschew. An overstatement to be sure but I hope useful!

Bill Meyer: Yeah, Smith works with the sound possibilities and historical associations of the string quartet, but he certainly isn’t bound by them, any more than he’s bound by the conventions of the modern jazz combo format in the Gold Quartet.

Marc Medwin: One of the most fascinating things about Smith's music is how often he broke with those conventions, going way back to that first trio with Braxton and Leroy Jenkins when they recorded those gorgeously transparent compositions The Bell and Silence!

Derek Taylor: Smith's placed himself in so many fertile contexts over the years that I often lose track of the taxonomy. The pioneering work with Braxton that you mention, Marc, but also straight up free jazz dates with Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, Marion Brown, Frank Lowe, and others, although he would likely call such idiomatic pigeon-holing unnecessary and reductive. The Yo Miles! fusion projects with Henry Kaiser and various encounters with John Zorn offer additional avenues. And Michael mentioned the Company conclaves earlier. Even the formats and assemblages he returns to (solo, duo, Golden Quartet...) share an enviable trait of retaining freshness.

Christian Carey: Others have touched on this, but the duos are primarily between musicians in their eighties. So many musicians, from Marshall Allen to Roy Haynes, have shown us that music keeps you young thinking and acting.

vimeo

Wadada Leo Smith’s 80th Birthday Celebration from Wadada Leo Smith on Vimeo.

Derek Taylor: Definitely true of Wadada, Christian. His beaming visage looks easily 20 years younger than his octogenarian age would suggest.

Michael Rosenstein: Sorry to have been lurking on this for a bit but July was a bit of a hectic month.

It’s intriguing to note that the duos with akLaff, Cyrille, and DeJohnette were all recorded within a fairly short period of time — the duo with Cyrille in September 2019, the duo with akLaff in December 2019 and the two discs with DeJohnette in early January 2020. (The duo with Bennink is from 2014, so quite a bit earlier.) The proximity of the sessions, the pieces he assembled and the history Smith had playing with each of his collaborators provides a certain through-thread to the set. But each of his partners bring their own sensibilities which comes through in each of the sessions. In the liner notes, Smith talks about wanting to see how he would respond “in each situation with a new drumming philosophy.”

Interestingly, the recording session with Bennink in Amsterdam in 2014 is what kicked off Smith’s idea to put together this recording project of drum duos. Bill references how Bennink “eschews both the antic side of his late free approach and his pre-bebop swinging brushes approach.” But, of all the sessions, not surprisingly based on his musical roots, I hear Bennink’s playing digging in most deeply to the jazz drum traditions. Of course, he extends and abstracts them, but hearing this session, I think back to hearing Smith play with Ed Blackwell (a fantastic meeting that Smith ended up releasing on Kabell.) Listen to the simmering snare rolls he calls up in “Louis Armstrong in New York City and Accra, Ghana” which swings like mad and elicits searing retorts from Smith. While more angular and pointillistic, “Ornette Coleman at the Worlds Fair of Science and Art in Fort Worth, Texas” also digs into those free-bop tendencies and Smith responds in kind. It’s also worth noting that, on this disc, in contrast to the rest of the boxed set, most of the tunes are collective improvisations credited to both players.