#longass!!! I'm going to post this half then just add the rest of the organisms as I do them. bit off more than i can chew etc

Text

Explanations for each creature from that poll (Part 1):

Firstly, about half knew one creature (I'm curious which!) and a quarter only one. A few knew most, and one knew them all. Very interesting!

Organism #1: Brachiopoda

In the post I said this isn't a bivalve(clams, mussels, oysters, a group which is relatively close relatives with snails and octopi), and that's correct! But essentially, it's an example of convergent evolution. Learn to filter feed really well, become hard and immobile. It's a strategy that pops up a lot. It has something called a lophophore. Thats essentially like a curtain of tentacles around its mouth. What's WEIRD about it is this lophophore is an extension of the coelom. Aka, the internal body cavity. As opposed to a dedicated organ; it's like if the space where your guts are processed stuff instead of your guts.

Beyond that, brachiopods are extremely common in the fossil record. They were very badly affected by the Permian-Triassic extinction event (P-T event, also known as The Great Dying, aka the worst extinction event so far because the entire ocean acidified), but have since recovered — albeit slower than their convergently evolved distant cousins, the bivalves.

How to tell the difference between a brachiopod and a bivalve?

The correct way is to say Brachipods have dorsal and ventral valves (shells), while bivalves have left and right valves. Which is kind of useless unless you're a huge nerd. I mean, you can still see it in the lines of symmetry a bit, but. Firstly, some brachiopods don't have closely connected valves at all (called inarticulate), so you know those are brachiopods. For the articulate brachiopods, they often have a gap or hole in the hinge for their stalk. Between that and the general shape, I find that easiest.

.

Organism #2: Platyhelminthes

Specifically, this is a hammerhead flatworm! Remember the coelom I just mentioned? The body cavity? Yeah they don't have that. They have no circulatory or respiratory organs... No blood vessels, no heart, no lungs. Everything has to work through diffusion! This is why the hammerhead flatworm is so amazing, because not only is it very large (which is hard to do when you're relying on diffusion) it also lives on land (which is hard to do when you're relying on diffusion). Unlike cnidarians (jellyfish, corals, and friends), they DO have specialized digestive and excretory systems. Since they rely on diffusion, large flatworms have branched guts that go all throughout their body so what they digest can get to all their cells! They use something called protonephridia to manage the toxins in their body — these are essentially proto-kidney cells.

Despite being very similar to another group called Acoelomorpha, who are sort of the base for all other bilateral animals, newer research thinks they're from later in the evolutionary tree and just retroactively lost a lot of what had been developed (such as a coelom and most organs. Wild)!

Free-living flatworms are often very small and cute, though there's larger ones like the hammerhead and the spanish dancer. Unfotunatelt, flatworms are very medically relevant: flukes and tapeworms are both specialized types of flatworms.

.

Organism #3: Siphonophores

Siphonophores are really cool! They're a type of cnidarian (jellyfish, hydrozoans, corals, sea anenomes, gorgonians). You know cnidarians as "those assholes in the ocean that sting me" mostly. Well siphonophores are notably really good at that.

In Cnidaria, you have the coral and sea anenome-like things (Anthozoa) and the jellyfish-like things (Medusozoa). Anthozoans don't really have a mobile stage in their life, while medusozoans do! Medusozoans go in between an asexual, sessile (immobile) polyp form, and a sexual, mobile medusa form (imagine what you normally think of when you imagine a jellyfish).

Within Medusozoa, there's (roughly) two groups. The ones who decided to emphasize the medusa form are called Scyphozoa, and are your true jellyfish. They still have that polyp form, but spend a lot of time in the medusa stage of their life and invested in it evolutionarily.

The ones who invested heavily in the asexual polyp stage are called Hydrozoa. They still have a medusa stage, but it's often extremely reduced, to basically a freefloating gamete. Here's some usual hydrozoans/hydroids:

Small, mostly an asexual clump of polyps. They're usually colonial — a bunch of clones, but connected through the gut. Fire coral is actually a hydroid which developed a calcium skeleton, and not a true coral!

What's really interesting is siphonophores are actually hydrozoans — they're very very unusual. They're those asexual polyps, they're a colony — but instead of the clones being identical, they specialize!

These are called zooids. They're akin to how we have specialized organs, like lungs, our livers, etc. Except. Each zooid is an entire clone of the original organism. They're all identical. But as part of the colony, they restrict and focus their development in certain ways. It's like if you were attached to another person, but they developed to just be a liver.

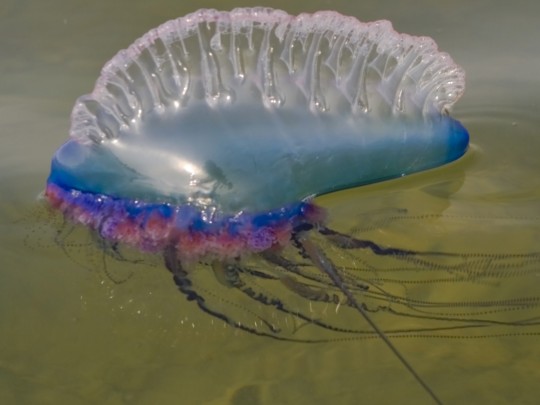

Most siphonophores are repeating sequences of certain zooids, mostly propulsion and digesting zooids. That's how they get so long. They have a very nasty sting, and thankfully most float down below where people normally go. However, there's a few that don't — notably, siphonophore's own atypical specimen, the Portuguese Man 'O War! Also known as a Blue Bottle. Pictured below.

It looks a lot like a normal jellyfish medusa, like from scyphozoa! But you can see, it doesn't have that very round shape. The big sail is actually one zooid, the tentacles are other zooids, it's all zooids! It's an entire colonial animal, as opposed to a true jelly, which is just one.

Since the siphonophore is made up of clones, do we call it a group of animals? Generally, no. Due to the specialization involved with zooids, we treat the entire creature as one animal. Many individuals, one organism. Admittedly, it's still very strange. Colonialism is actually very common within cnidaria, as it serves to help cope with the lack of specialization opportunities due to not having an internal body cavity (and thus stuff like mesoderm). That said, even some animals with mesoderm and body cavities have evolved colonality, though I can't think off the top of my head of an example with such a degree of specialization of each zooid like siphonophores have.

.

Ending the post here for now, and I'll add the other organisms in subsequent reblogs. I hope this inspires interest in biology and evolution for you and lets you know about things you would've never even realized as possible!

#marine biology#invertebrates#longass!!! I'm going to post this half then just add the rest of the organisms as I do them. bit off more than i can chew etc#Feel free to ask questions! This is pretty advanced stuff outside of certain spheres#It's also meant to serve as a jumping off point for your own research if you'd like. don't know a word? look it up!#if you're still confused I can try to help#did my best to keep it broadly accurate but I'm running the line between simplification and specificity

7 notes

·

View notes