#lm 2.8.5

Text

#my posts#les mis#les miserables#victor hugo#lascelles wraxall#wraxall translation#lynd ward#lm 2.8.5

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

This shouldn’t be as funny as it is:

“Fauchelevent had expected anything but this, that a grave-digger could die. It is true, nevertheless, that grave-diggers do die themselves. By dint of excavating graves for other people, one hollows out one’s own. [ . . . . ]

“Father Mestienne is the grave-digger.”

“After Napoleon, Louis XVIII. After Mestienne, Gribier. Peasant, my name is Gribier.””

“Grave-diggers can also die” is a wild plot twist, especially since Hugo portrays it as a shocking fact. And Gribier’s matter-of-fact attitude (and his listing of political events, as if all of this is just “natural” turnover) is humorous in a dark way.

Gribier himself is fascinating. The fact that he has to provide for seven children links him to Jean Valjean, who had to care for the same number of children before his imprisonment. His need to work, then, is desperate, as we know just how hard it is to provide for so many. Avoiding drinking is one way of saving money, but it also speaks to the deprivation of small enjoyments for the poor. Drinking isn’t just a pleasure in itself, but a major way of socializing, as Fauchelevent notes here; by not accepting drinks, Gribier is not only dodging an expense, but a chance to get to know his coworker, one of the few people he has a chance at bonding with in a life dominated by work. Of course, this expense isn’t just hard on him. Fauchelevent is also nervous about the idea of paying for drinks, highlighting his own financial struggles. But Gribier is also even worse off, working two jobs and still having this worry. It’s notable that his jobs mean he literally works day and night: he writes by day and digs by night, not having any real time to rest. The extent to which he can keep this up is debatable. He doesn’t complain of the hours, but he does say that digging is ruining his hand, which he needs to write. He’ll ultimately be forced to choose, losing the funds of one job and likely his dream of writing. Work has consumed his life because he has no alternative if he wants to feed seven children, just as it had taken over Valjean’s existence.

Although the parallel to Jean Valjean is more blatantly referenced through the number, Gribier bears an even closer resemblance to an early Fauchelevent. When we first encountered him, Fauchelevent had just fallen on hard times, losing all the relative comfort he’d had as a notary but maintaining a sense of pride and superiority from that status. Gribier is certainly poor if he works all day and all night, but he also specifically came from an educated class (having studied even more than Fauchelevent). He’s fully literate, speaking of the examinations he’s passed; how he was destined for a career in literature; using words Fauchelevent can’t understand; and referencing philosophy in the middle of their conversation. His contempt for Fauchelevent also links to a rural-urban divide, with him addressing him as a “peasant” and a “rustic” to stress the differences between him, an educated Parisian, and the convent gardener from the countryside. His pride is even more extreme than Fauchelevent’s was, although he doesn’t necessarily have a specific target for his bitterness at his loss of status (unlike Fauchelevent with Father Madeleine). Gribier is doubly dangerous, then. On the one hand, his poverty keeps him from building ties with people that could ultimately create a system of support for him and bring him closer to others. On the other, he rejects these ties on the basis of his past status. He can’t feel solidarity for Fauchelevent if he feels superior to him, and while he does address him as “colleague,” he largely seems to look down on him.

This parallel is particularly interesting given that Fauchelevent is depicted the way Valjean typically is in this chapter. We see him as an outsider would, only being told who he is later on. We may know that Fauchelevent actually has quite a bit in common with Gribier, even if they differ because of their origins (city vs countryside) and the extent to which they rose and fell class-wise. But Gribier only sees that image from the beginning of the chapter: an elderly worker limping behind a hearse.

#les mis letters#lm 2.8.5#fauchelevent#gribier#jean valjean#he's such a fascinating character!! even if he's so frustrating#the coffin heist is dramatic enough without outside obstacles but unfortunately#nothing can ever go so smoothly for Jean Valjean :(

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

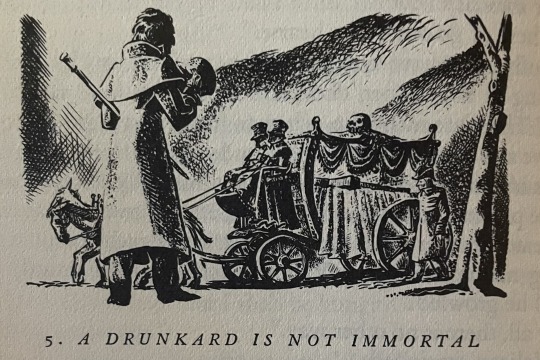

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - It is Not Necessary to be Drunk in Order to be Immortal, LM 2.8.5 (Les Miserables 1967)

Fauchelevent surveyed this stranger.

“Who are you?” he demanded.

“The man replied:—

“The grave-digger.”

If a man could survive the blow of a cannon-ball full in the breast, he would make the same face that Fauchelevent made.

“The grave-digger?”

“Yes.”

“You?”

“I.”

“Father Mestienne is the grave-digger.”

“He was.”

“What! He was?”

“He is dead.”

Fauchelevent had expected anything but this, that a grave-digger could die. It is true, nevertheless, that grave-diggers do die themselves. By dint of excavating graves for other people, one hollows out one’s own.

Fauchelevent stood there with his mouth wide open. He had hardly the strength to stammer:—

“But it is not possible!”

“It is so.”

“But,” he persisted feebly, “Father Mestienne is the grave-digger.”

“After Napoleon, Louis XVIII. After Mestienne, Gribier. Peasant, my name is Gribier.”

#Les Mis#Les Miserables#Les Mis Letters#Les Mis Letters in Adaptation#LM 2.8.5#Fauchelevent#Gribier#Bert Palmer#les Mis 1967#Les Miserables 1967#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#lesmiserables1967edit#pureanonedits

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my favorite chapters of book 8! The entire situation of confusion and "even the grave-diggers die" is inherently funny. However, it also poses a serious trial for poor Fauchelevent (and brings new sufferings for Jean Valjean).

Fauchelevent is not a natural improviser! (And perhaps that's why he wouldn't make such a great spy, as we had hoped a few days ago.) It's evident that he needs time to adjust to new social situations and changing circumstances. He is slow in digesting the new reality. Nevertheless, he tries hard to push through his agenda (like persuading the new grave-digger to go and have a drink), just as he pushed through his agenda (the need to employ his "brother") in his conversation with Mother Innocente.

@dolphin1812 made excellent observations about Gribier! There's not much to add, except that Hugo made his best to make him rather disagreeable. His arrogance (constantly addressing Fauchelevent as "peasant" and "villager") is truly irritating.

I quite enjoyed the comparison of the two cemeteries: on one hand, the Vaugirard cemetery - "a faded cemetery" deserted even by flowers, abandoned by the bourgeois because it "hinted at poverty," and on the other hand, the fashionable and elegant Père-Lachaise (compared to "mahogany furniture"). It was only a few decades ago that it was difficult to persuade the bourgeois to bury their dead in Père-Lachaise!

Now I am haunted by the image of "a coffin, covered with a white cloth over which spreads a large black cross, like a huge corpse with drooping arms."

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 2.8.5 ‘It is not enough to be a drunkard to be immortal’

In this hearse there was a coffin covered with a white cloth, upon which was displayed a large black cross like a great dummy with hanging arms.

OKAY THEN. This book is very in favor of Christ imagery overall, but it’s sure not going to be pro-clerical today, it seems.

Now that we’ve gone over the heist plot in enough detail to absolutely ensure it will go wrong, we zoom all the way out to see it unfold.

@fremedon has already pointed out that the safety rules and regulations for the cemetery gates, whatever else they may accomplish, are designed to harm the poor specifically--in this case, grave diggers.

Last chapter seemed to raise a number of red flags for me about the meaning of Mother Innocent’s plans--her focus on the dead over the living, on tradition over progress, her reversals of the patterns of the barricade--but this chapter shows the similarities of the convent and the barricade. It is a little republic, and it believes in what is right, not what is lawful.

First the rules; as to the code, we will see. Men, make as many laws as you please, but keep them for yourselves. The tribute to Cæsar is never more than the remnant of the tribute to God. A prince is nothing in presence of a principle.

I’m thinking, of course, of Mellow’s Convent Gardener Javert and the near-heart attack this is going to give him when he finds out his conservative, rule-abiding new masters are Also Made Of Crime.

We see a bit of the gloating Slytherin in Fauchelevent, which I like a lot--I’m getting a much clearer sense of his character this time through. He starts gloating, of course, immediately before it all goes to hell.

He was a long, thin, livid man, perfectly funereal. He had the appearance of a broken-down doctor turned grave-digger.

Fauchelevent burst out laughing.

"Ah! what droll things happen! Father Mestienne is dead. Little Father Mestienne is dead, but hurrah for little Father Lenoir! You know what little Father Lenoir is? It is the mug of red for a six spot. It is the mug of Surêne, zounds! real Paris Surêne. So he is dead; old Mestienne! I am sorry for it; he was a jolly fellow. But you too, you are a jolly fellow. Isn't that so, comrade? We will go and take a drink together, right away.”

The discordant visual of Fauchelevent saying this to this corpse-faced undertaker is hilarious in a way I’m sure I’ve seen it in movies. Hugo is so very cinematic.

It’s also an interesting commentary on doctors, too, whom Hugo is usually notably positive about, for his time? What little I’ve read of Sue’s Mysteries of Paris, for instance, is dramatically negative about doctors and contemporary medical practices. Other writers seem to have other dark things to say about doctors and medical students. But with Hugo, we’re looking at Joly & Combeferre, plus a few extras who are usually forces of kindness, even when they can’t do much.

Gribier almost resembles Myriel for a moment:

“The good God," said the man authoritatively. "What the philosophers call the Eternal Father; the Jacobins, the Supreme Being.”

Except that he’s not engaging meaningfully in naming of God. He seems to be using his education to run rhetorical circles around Fauchelevent, because he can, and because he likes to feel superior.

We end at the open grave. Fauchelevent is worried.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

LM 2.8.5 (retrobricking)

I lovehate the 15-franc fine; it’s a terrible idea in exactly the way so many similar policies are. A 12 year old could see it’ll only affect the people who have a reason to be in there (the gravediggers, maybe mourners too lost in grief to notice the time) -- anyone breaking in for vandalism is just going to break back out. But hey, here’s a 15 franc fine! to deter those dastardly ..gravediggers...from not ...having their paperwork, I guess?? I’ve no idea if Hugo invented it, but I could easily believe he didn’t have to; it feels like the sort of thing that just Would Exist. It’s a policy that isn’t trying to hurt the people it will hurt , exactly--but it’s definitely there to hurt someone, and can only do that one thing. It won’t help anyone at all, not even the dead.

I’m struck that , just as Valjean’s escape into the convent could only happen in the era of the streets being lit by candle-lamps, his escape out of the convent could only happen in the day of this particular cemetery. In 1830, it will no longer be an option, replaced by the Montparnasse. On one hand , constantly drawing attention to these in the way Hugo does kind of gives Valjean’s adventures a fairy tale feeling--happening in a land Far Away, even while it’s all France.

But on another level--everything about Valjean’s escapes depends on transient little realities of each new era , but his status as a social outcast crosses over over lines of governments, decades, and even centuries. That is , as the old texts say, Kind Of A Bummer.

#LM 2.8.5#I WAS just gonna try to catch up on the gamin digression but then...all this.XD#other people's posts are Too Interesting#brickclub

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 2.8.4, “In Which It Seems Jean Valjean Might Well Have Read Austin Castillejo,” and 2.8.5, “To Be Immortal It Is Not Enough To Be A Drunkard”

Valjean is so much calmer now that he has a plan, even if it is a ridiculous plan. And from his POV, it’s a comfortable one--all he has to do is hold his breath, wedge himself into a tight space, and fake his death. Easy-peasy; that’s how he got out of prison.

(After this, he will have died and been reborn through fire (burning his papers in the M-s-M town hall fire), water (the Orion), and earth--not quite a canonical Threefold Death, but certainly suggestive. He’ll pass through earth and water simultaneously in the sewer, but he doesn’t manage to turn that death into a real rebirth.)

Fauchelevent, more skeptical of the plan to start with (and not unreasonably so), is skating awfully close to hubris by the time we get to the cemetery: “What remained to be done was nothing. In the last two years he had got that chubby-cheeked fellow good old Mestienne the gravedigger drunk at least ten teims. He could work him like a puppet. He could do what he wanted with him. Fauchelevent could shape him to his will and his whim. Mestienne’s head would fit the hat that Fauchelevent put on it. Fauchelevent felt utterly confident.”

The whole plan depends on Fauchelevent’s utterly assured social engineering--and that is what will ultimately save the day--but he has not planned for every contingency: “Fauchelevent had expected anything but this, that a gravedigger should die. Yet it is true: even gravediggers die.” (I don’t know why I find this line so funny, but it is always hilarious. Fun fact! Gravediggers die!

Random observations:

--I love the description of Vaugirard Cemetery; the settings continue to be over-the-top Gothic in the best way.

--Vaugirard is also our first, but not last, look at an unfashionable burial-ground, not much visited and poorly cared for. Though Valjean is buried in Père-Lachaise, just at the low-rent end of it.

--Perronet, the architect of the gatekeeper’s lodge, also designed the main Paris sewers. I don’t even know what to do with that.

--We get as much description of the administrative details of the cemetery as we do of its atmosphere--possibly more--and it’s equally creepy. When bureaucracy intersects Valjean’s life, it is never good.

(And it’s not good for misérables generally, as we’ll see more of in the next chapters--the heavily regimented burial regulations, and restrictions on public access to the cemetery, stem from well-intentioned and reasonable (to a miasmatist) sanitary codes, but the 15-franc fine for violating them, probably intended to deter trespassers, falls on the manual laborers doing the actual work of public health.)

4 notes

·

View notes