#j. c. leyendecker & american masculinity

Text

More samplings from "J. C. Leyendecker & American Masculinity". On exhibit from May 5th to August 13th, 2023.

In relation to the text on the banner, it's also interesting to note that according to a credible art historian and creative director who did a panel related to the exhibit, Leyendecker uniquely had ownership of his images written into all his contracts. This meant that the company licensed one-time or limited-time usage for the work-for-hire image and sent the original back to Leyendecker.

You may also be interested in checking out @breakingthegaycodeinart on instagram.

#I love the frames on these two pictures and the layout of this whole wall#secret: I loved the frames on all of the pictures in this gallery#framing is something I keep thinking about lately and focusing on when I visit museums and it's making me want to relisten to#Within the Wires season 2#j. c. leyendecker#homoeroticism#art history#j. c. leyendecker & american masculinity#These paintings don't exemplify it as much as others but#Leyendecker's ability to manipulate perspective to draw emotional or physical connections between subjects and his use of black to create i#illustrations#art#queer history#queer art history

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE FRIDAY PIC is the J. C. Leyndecker painting used in an ad for Kuppenheimer menswear in about 1920, from the little Leyendecker survey now at the New-York Historical Society.

I wrote about that show in Friday's New York Times, and that text is copied below. But after publishing my piece, I had a new thought about its comparison between Leyendecker and Picasso. I admit that I only meant the comparison as a rhetorical gambit, but I now think that there's a credible art-historical connection between the two figures.

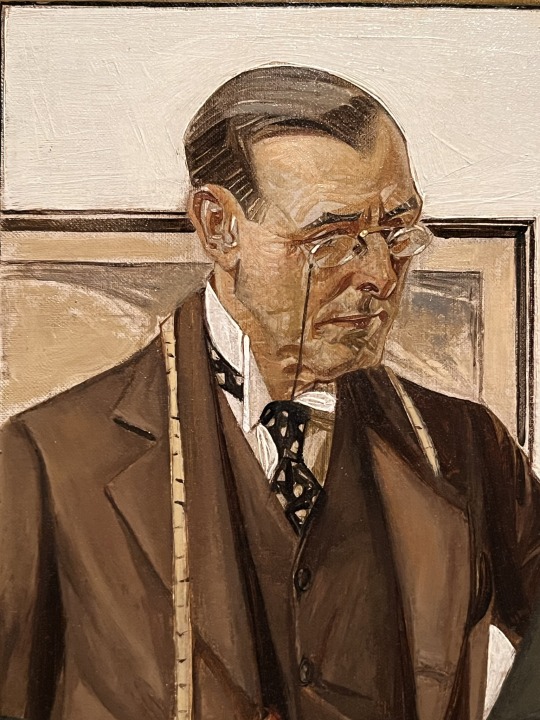

In the painting reproduced in his collar ad, Leyendecker is very visibly, aggressively deploying what a painter friend of mine calls the "rectilinear brushwork" that's a feature in certain Old Master-ish artists, beginning maybe with the great eighteenth-century portraits of Henry Raeburn. That brushwork is at the root, I think, of the similar facture that you see in Picasso's Cubism and its so-called "passages," where I think it stands for the connection that Picasso was always keen to assert to the art that came before him, to show how he transformed it. As I said in the Times, Leyendecker also wanted such a connection, in his case to act as camouflage for his radically queer subject matter. But I now wonder if he's also secretly nodding to Picasso, to tie his new erotics to the latest in modern art and thought.

That makes Leyendecker not only a predecessor to Robert Mapplethorpe, but also to Robert Ryman.

--------

Here's my New York Times piece:

J.C. Leyendecker: The ‘Arrow Collar Man’ Who Hid a Radical Idea

The celebrated illustrator shaped American visual culture in the 1900s, but his traditional imagery carried a defiant queer message.

By Blake Gopnik

June 29, 2023

As the 20th century got well underway, who was more radical, Pablo Picasso in Paris, or Joseph Christian Leyendecker in New York? I asked myself that as I toured “Under Cover: J.C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity,” a fascinating show at the New-York Historical Society. In a score of paintings and countless magazine pages, it gives a compact survey of Leyendecker’s work across the first three decades of the last century, as one of this country’s celebrity illustrators.

His calling card was male beauty: Jazz Age youths in their finest finery populate his ads for shirts and starched collars; athletic collegians grace his covers for the weeklies.

Picasso did amazing things to the surface of his pictures that Leyendecker’s crisp realism couldn’t match. But just because Picasso’s radicalism was visible right there on that surface, it was easy to take steps to avoid it. Whereas Leyendecker’s wildly successful illustrations were simply unavoidable. In 1908, a popular magazine felt it worth reporting that, at 34, Leyendecker was booked 12 months in advance and charged the vast sum of $350 for one commercial illustration — what an ordinary worker might have earned in a year.

That meant a large part of the public had no choice but to encounter the radical idea that hid under the traditional surfaces of his imagery: that two elite men could be in love, or in lust, and might even be the happiest of long-term couples.

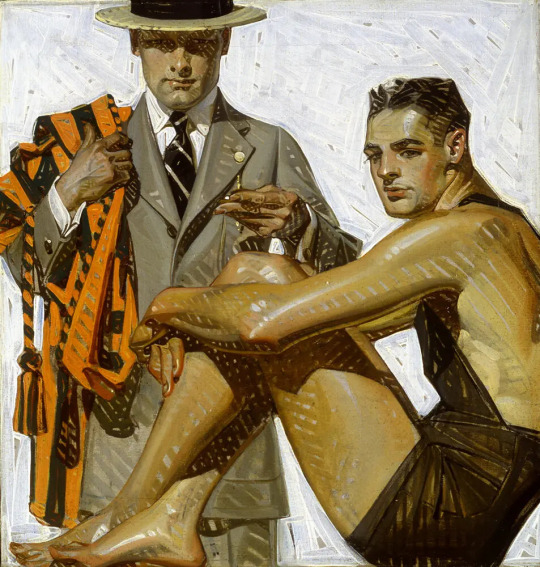

Those with the will to see could not have missed the possibility that romance is budding, or maybe already blooming, between the two square-jawed hunks in Leyendecker’s 1920s ad for Kuppenheimer menswear. One man is immaculately dressed in gray suit and boater, the other at ease beside him in a one-piece swimming costume.

Contemplating the two men in an ad for Arrow collars, lounging of a morning in an Ivy League club, it takes just the smallest skip of the imagination to think that Leyendecker introduces them to us as mere bosom buddies only because it would be rude to tell some more explicitly amorous story.

Even in the Jazz Age, when homophobia was less aggressive than it later became, to offer up such scenarios to the mainstream was more outrageous — more silently, secretly outrageous — than anything Cubism’s show-offs could propose. I think of Leyendecker’s art as a Trojan horse that released a gay fifth column into American culture, undermining the majority’s straight erotics in preparation for the uprising that came in 1969 outside the Stonewall Inn.

Dan Guadagnolo, one of several scholars studying Leyendecker’s queer culture, has written about how the illustrator “generated commercial appeal among normative men while simultaneously offering a novel vision of middle-class white queer masculinity for those who might experience same-sex desire.” Queer identities had barely begun to jell in Leyendecker’s era; his images helped a nascent gay culture imagine itself folded into the American power structure, however remote that reality might still have been. After Leyendecker took up with his life-partner, Charles Beach — who modeled in that bathing suit and for many other ads — he felt the need to withdraw from public life into the privacy of the mansion his works had bought them.

Norman Rockwell, 20 years younger than Leyendecker and eventually his neighbor, writes quite brutally in his memoir about how Beach had “insinuated” himself into Leyendecker’s life and especially about the duo’s social withdrawal once he had. Leyendecker told Beach to burn his papers and art upon his death, in 1951, but luckily a few of the pictures were spared.

Leyendecker painted those pictures with all the bravura of a great society portraitist — of a Gilbert Stuart or a John Singer Sargent — but with every gorgeous lick of paint magnified and exaggerated so it would come through even in reproduction on the printed page. That showy technique was faux-conservative camouflage, I think, for the defiant message hidden beneath.

Most members of the American mainstream might have been too blinkered to recognize that defiance. But I can’t shake a mental image of the artist and Beach at ease in their mansion, reveling in their ads’ secret subversion. As a gay couple, how could they not have recognized it in the male duos so lovingly portrayed? There’s one case where the subversion was barely hidden at all: In an ad for Ivory Soap, the shadow Leyendecker placed on his model’s crotch seems clearly to hint at an erection, according to an exhibition wall text. You can’t unsee it once it gets pointed out.

Leyendecker’s queer daring could have played a role in his market success. The gorgeous young Ivy Leaguers in his ads seem the epitome of privilege — more privileged, certainly, than the working stiffs actually meant to buy the clothing being pitched. And what could have been a greater sign of privilege than the freedom to love anyone you fancied, of any gender? Choose an Arrow collar, those ads imply, and you’ll soon have the same power to make choices as the elites.

Just what’s being chosen is beside the point: Many American men might have been horrified at the idea of sleeping with another man. But Leyendecker’s imagery gets at the very idea of untrammeled choice. You might say that imagery stands, subliminally, for the unending options that American capitalism had started to offer consumers.

Compared to the freedom that Leyendecker puts on the table, Picasso’s preference for facets and angles hardly counts as all that unfettered.

Under Cover: J.C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity

Through Aug. 13 at the New-York Historical Society, 170 Central Park West, Manhattan; (212) 873-3400; nyhistory.org.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I couldn’t go to the J. C. Leyendecker exhibit on masculinity without sharing some of the highlights here on the J. C. Leyendecker fansite

The exhibit is open through August 13th, 2023

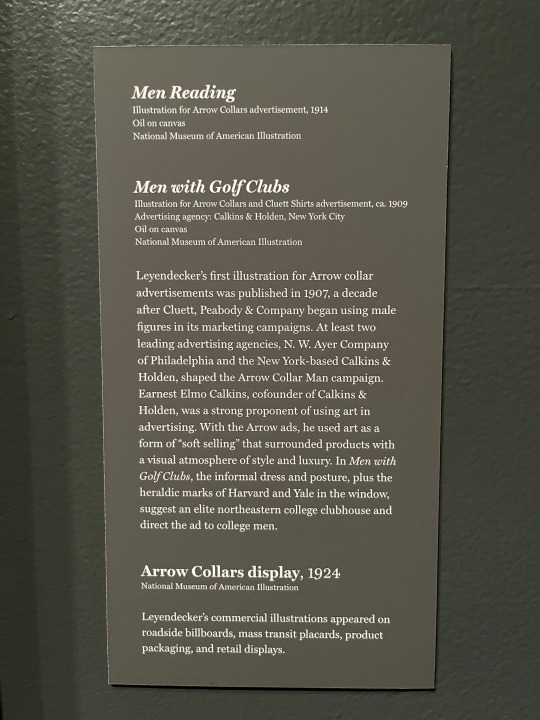

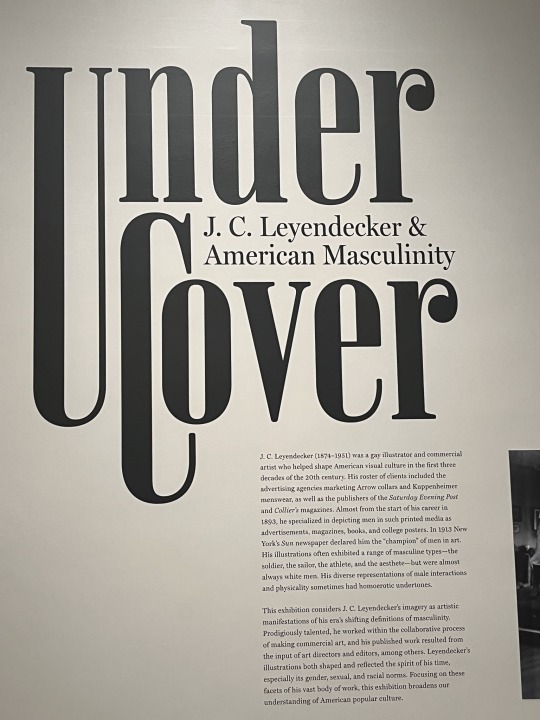

[ID for 2nd image: Title of the exhibit and preface text painted on the wall outside of the entrance to the exhibit, reading: "Under Cover: J. C. Leyendecker & American Masculinity.

J. C. Leyendecker (1874-1951) was a gay illustrator and commercial artist who helped shape American visual culture in the first three decades of the 20th century. His roster of clients included the advertising agencies marketing Arrow collars and Kuppenheimer menswear, as well as the publishers of the Saturday Evening Post and Collier's magazines. Almost from the start of his career in 1893, he specialized in depicting men in such printed media as advertisements, magazines, books, and college posters. In 1913 New York's Sun newspaper declared him the "champion" of men in art. His illustrations often exhibited a range of masculine types—the soldier, the sailor, the athlete, and the aesthete—but were almost always white men. His diverse representations of male interactions and physicality sometimes had homoerotic undertones.

This exhibition considers J. C. Leyendecker's imagery as artistic manifestations of his era's shifting definitions of masculinity. Prodigiously talented, he worked within the collaborative process of making commercial art, and his published work resulted from the input of art directors and editors, among others. Leyendecker's illustrations both shaped and reflected the spirit of his time, especially its gender, sexual, and racial norms. Focusing on these facets of his vast body of work, this exhibition broadens our understanding of American popular culture." end ID.]

#my other post got fucked and I couldn’t edit it so I’m reposting#j. c. leyendecker & american masculinity#image described#illustrations#j. c. leyendecker#charles a. beach#jc leyendecker#art history

11 notes

·

View notes