#he's more critical of others than himself in certain aspects and cleanliness is one of those times

Note

What do you think Toby’s relationship is with alcohol and stuff like smoke? You think he gets triggered like what if Tim were to smoke infront of him (pretty sure Frank smoked?) would he get triggered or something?

ooo ok ok. tw for mentions of abuse, alcoholism, etc under the cut

toby represses stuff very heavily. after about 3-4 years post-killing his dad, (so he'd be about 20+), he'd just not think about it. it's not that he's "healed" by any means, but he just think he has bigger things to worry about

he feels a bit more towards alcohol than cigarettes, and he'd get irritated with Anybody who drank ages 17-19. but, his mom would have a few glasses of wine every now and again, and it just relaxed her. she would just kinda sit in her chair and watch tv quietly. occasionally toby would find her weeping. so he knows that alcohol isn't like, strictly an agent of destruction and abuse and all things horrible (not that he thinks its good in any way)

if he knows someone is more of like, a goofy 'fun' drunk, or an emotional crying drunk, or immediately wanting to sleep, or anything along those lines - he doesn't really care. he drinks socially, though he never really gets further than being tipsy. he hasn't sworn it off or anything, he doesn't have that much self restraint

BUT if he notices that someone is more aggressive when they're drunk, even if it's just confrontational rather than violent, he gets irritated. often he'll egg them on and purposefully try to get into a fight with them, calling them sloppy and say they're embarrassing themselves and whatever. it's probably because thats the shit he'd NEVER get to say to frank without risking the entire family, and because he just wants their drinking to be as unpleasant as possible.

frank would smoke in the same damn armchair everyday and night, missing the ashtray half the time. so toby has an issue with people smoking indoors and being careless with cigarettes, he thinks it's ridiculous and dirty and whatnot. so he'll probably get aggravated and say something if someone is smoking indoors. BUT tim also thinks its gross smoking indoors, so he only does it outside - which toby's fine with. he gets pissed if he sees tim just leaving used cigarettes lying around

it's not so much that he'll be triggered in the sense of a flashback and begin crying and whatnot, but he'll get irritated if things fit into a certain memory or resemble franks aggression/carelessness. and he'll say something everytime, he's not the type to bite his tongue - especially now that he can defend himself

TLDR; he doesn't mind unless a drunk person gets aggressive or someone smokes indoors. he drinks socially at times. he doesn't smoke cigarettes.

#TY FOR ASK#i wrote this at 8am i hope its coherent#creeped#hcs#asks#idk if i mentioned that i sorta hc toby as like#not a cleanfreak by anymeans#but i specified he grew up in a very military strict household that needed to be spotless at all times for a while#so he gets irritated when other people are dirty and leave messes...#though he'll prob do it and be like :) its my mess my house idgaf#he's more critical of others than himself in certain aspects and cleanliness is one of those times

83 notes

·

View notes

Note

May I please ask what your preferred dynamic between Holmes & Lupin would be? (From what I can tell, the term 'frenemies' might have been invented for these two - if any two characters in fiction WOULD spend all their time trying to one-up each other it's these two, if only their diverse other commitments, challenges & interests left them the free time to do so: I'm also morally certain a sadly-hypothetical Holmes/Lupin team is one of the few things that could bring down Fantomas for Good).

I think "frenemies" is what ultimately works best for these two specifically, because there's a certain untouchability to icons as big as these two that limits the potential stories you can tell with them (although yes, definitely on board with the two having what it takes to bring down Fantomas, although probably not as cleanly and easily as they might expect).

The original Leblanc stories involving this premise are very much centered around one-upmanship, even embracing a theme of national rivalry of England vs France. They acknowledge Holmes's talents but without the awe, with a somewhat aged Holmes with mundane imperfections easily exploited by the daring young thief, someone deserving of his legend but who doesn't quite live up to it. Obviously Lupin's gotta have the upperhand, not just because it's his author writing it, but because the whole point of Lupin's creation was to be the new hotness, the counterpart to both the stuffy old Great Detectives as well as the aristocratic master burglars, and really, what kind of rising superstar would he be if he couldn't put one over the other guy? If he's gonna live up to his claim of being the greatest criminal ever, he's gotta be able to humble the greatest detective at least a little.

The treatment of Watson (Wilson) is tasteless and it's frankly a bit saddening to see that even back then writers were still shitting on Watson far too much, but on the whole I think Leblanc was a lot fairer to Holmes than he could have been (certainly other writers from this time period who added Holmes to their stories were not as fair), he makes it very clear Holmes is not just another Ganimard out of his depth and is very much as close to an equal Lupin's ever had. I think the description used to cap off their final meeting is very much on point:

"You see, monsieur, whatever we may do, we will never be on the same side. You are on one side of the fence; I am on the other. We can exchange greetings, shake hands, converse a moment, but the fence is always there.

You will remain Herlock Sholmes, detective, and I, Arsène Lupin, gentleman-burglar. And Herlock Sholmes will ever obey, more or less spontaneously, with more or less propriety, his instinct as a detective, which is to pursue the burglar and run him down, if possible.

And Arsène Lupin, in obedience to his burglarious instinct, will always be occupied in avoiding the reach of the detective, and making sport of the detective, if he can do it. And, this time, he can do it" - Arsene Lupin vs Herlock Sholmes

The consistent outcome is that Holmes "wins" the material battle while Lupin gets away with the spiritual or karmic victory. The first story, Holmes has Lupin figured out from a glance, robbing him of his greatest asset, and Lupin even tells Holmes under a guise that he has no greater admirer than himself. Holmes choses not to arrest Lupin, and instead solves the mystery as quickly as Lupin would. But he is also, well, inferior. His "commonplace appearence" dissappoints the guests and detectives at the crime scene, he doesn't resemble their expectations, he is gruff, ungracious, arrogant and all-business, an Englishman all the way, and Lupin one-ups him by returning to him his stolen watch, and Holmes is not a good sport about it.

The whole "Herlock Sholmes" name change, although it was out of legal obligation, almost reads like a cheeky courtesy of Leblanc, like he's giving Holmes enough of a courtesy in sparing him the embarassment of being the loser. And the following adventures stay consistent: Sholmes is smart, as smart as Lupin, and he's a gentleman. But he isn't as smart as he thinks he is, and he isn't as much of a gentleman as Lupin. He resorts to unsporting tactics like intimidating Lupin's lover and involving the police in their conflict, and in the end, he's solved the crime, but "sown the seeds of discord" in a family Lupin was protecting, becoming the villain for a change, a role reversion Lupin openly laughs at. Holmes wins the "loot", he wins the material battle, but Lupin has the last laugh, and despite being a self-proclaimed villain, Lupin gets the moral victory.

It's a quite unflattering view of Holmes and one perhaps not suited for a crossover outside of the specific context of Holmes being the old and stuffy intruder in an Arsene Lupin story. Then again, every great hero needs a lesson in humility every now and then.

There's a particularly interesting variant of this dynamic to be found within China's own takes on Sherlock Holmes and Arsene Lupin.

Sherlock Holmes was quite the breakout hit for Chinese audiences at the time of his release, revered as an alternative to Judge Bao and the court-case novels. It's estimated that from 1903 to 1909, detective fiction constituted over almost 50% percent of all Western translated fiction, and with Holmes followed others like Nick Carter and Charlie Chan, and then Arsene Lupin, and soon their own local versions. The most famous and popular of which was Huo Sang, created by Cheng Xiaoqing, who was one of the main translators for Conan Doyle's stories. Cheng Xiaoqing even wrote his own take on Sherlock Holmes vs Arsene Lupin called "The Diamond Necklace", intending on correcting Leblanc's take, although interestingly, he unintentionally recreates the exact outcome by giving Holmes an unsporting attitude, where he "wins" only because Lupin lets him, and Lupin gets away again with the moral high ground. He would fare off much better in correcting Holmes with his own character, Huo Sang.

Huo Sang has a lot of similarities to Holmes, even with his own Watson counterpart, but was also designed to represent a few more traditional Chinese values. He is a science teacher with no addictions who belittles the wealthy class and fights for the poor, and he is praised for humility, one story even making a point to criticize Holmes for arrogance. He is a very Westernized character, with suits and guns and cigarettes galore, but the books were very dictatic and the author marketed them as "disguised textbooks for science", playing up on a newfound social reverence to scientific methods and self-improvement and national rejuvenation.

The stories deal heavily with corruption of the police force and institutions. In the earlier stories he outright calls police detectives useless rice buckets only good for solving petty thefts and preying on those that can't defend themselves, and while they become less sinister in later stories, Huo Sang's relation with law enforcement is much more frayed than Holmes's own. He uses dirty police tactics of his own and sometimes takes the law into his own hands, thinking the law cannot possibly achieve justice on it's own. His biggest loyalty is to his country and he values his reputation above all else. He values justice more than the law, like Holmes. But like Holmes, he still prefers to work inside the law and within Chinese traditions.

"Bao Lang, you scholar, you're too idealistic. Don't you realize how weak the law is in modern society? Privilege and power, favors and money - the law has all these deadly enemies

"We investigate half to slake our thirst for knowledge, half out of duty to serve and uphold justice. In the realm of justice, we are never constrained by the wooden and unfeeling law. For in this society, which is gradually tending to surrender its core to material things, the spirit of the rule of law cannot be put into general practice, and the weak and ordinary people are aggrieved, more often than not unable to enjoy the protection of the law.

Lu Ping, as you'd expect from a counterpart to Lupin, was much different. In fact, right in his very first story, he was already pitted against Huo Sang and outsmarting him, in a story called "Wooden Puppet Play". The character is inspired by an already existing tradition within Chinese literature of the "chivalrous thief", shapeshifting masters of deception and martial arts, and considered admirable and benevolent opposite to the corrupt government officials they outwit.

His stories are more whimsical, energized, more varied, less dedicated to strict science. He whistles while committing crimes, is identifiable by a red tie and wooden puppets he uses to signal his goons on what outfit he's gonna be wearing, and even cracks asides to the reader. In many aspects Lu Ping is influenced by hard-boiled Western detective stories, and naturally, he has a much more contemptious view of the law than Huo Sang

Well then, was he willing, in his capacity as thief, to represent the sanctity of the law and catch the murderer? Yes, he would be quite happy to round up that murderer. But he wasn't at all willing to boost the reputation of the law. He'd always felt that the law was only something like an amulet that certain smart guys had fabricated to get them out of embarassing situations.

Such an amulet migh be good for scaring away idiots, but it oculdn't threaten the violent, crafty and arrogant evil ones. Not only could it not scare them away, a lot of them hid right behind it to work their evil tricks!

Conflicts between these two are not just rooted in one-upsmanship or the patriotic conflict between the two, but instead in two differing approaches to justice, their influence on fellow Chinese writers to step outside tradition, and the respective ways they address issues in society. Additionally, it's not just a conflict between Great Detective vs Gentleman Villain, but the Holmesian Detective and the Hardboiled Detective. And, naturally, when the two met, a pattern reocurred again.

Writing a Lu Ping tale in his usual manner, Sun Liaohong deprives the detective of the advantage he typically enjoys at the hand of Cheng Xiaoqing or any other follower of Conan Doyle - narration by the detective's coadjutor.

It is Huo Sang who slinks around like a thief, alarming hotel service personnel. He becomes rattled, and even so is vain and arrogant. He is a bit too positivist about searching for clues, and he spends a remarkable amount of time just relaxing and waiting for something to happen.

The figure of "wooden puppets" turns wicked when the author uses the term to refer to Huo Sang, Bao Lang, and the police. Satirizing the genre as a play in which the author woodenly manipulates his character. But Lu Ping as puppet is a genius, moving from one identity to another, whereas Huo Sang is a dumbbell - wooden indeed, bourgeois, ridiculed.

A gentleman's agreement occurs only at the end. Huo Sang has the formal victory. He frees Lu Ping in order to get the paining, but the exhibition is held a day late and it now bears Lu Ping's seal.

In wartime, peace talks, diplomacy and gentlemen's agreements are just smoke screens, the stuff of puppetry. Both Huo Sang and Lu Ping surround themselves with lies to reach their final accomodation. Perhaps they are both puppets - Chinese Justice, the Fiction: Law and Literature in Modern China, by Jeffrey C. Kinkley

Both characters were canned in 1949 when the CCP banned detective fiction, and it was replaced with anti-spy literature about how the party police would expose counterrevolutionary conspiracies. They never got to have a rematch, and to my understanding there were a couple of films made afterwards about them, Huo Sang had a very recent one in 2019, but never another meeting.

I guess the takeaway here time and time again is that, credit to Holmes and all, but:

#replies tag#pulp heroes#pulp fiction#sherlock holmes#herlock sholmes#arthur conan doyle#arsene lupin#maurice leblanc#lupinchads can't stop winning

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flame Panda: worth the hype?

Introduction

For those of you who are pretty invested in handmade, hand welted, MTM boots, Flame Panda needs no introduction. In fact, if you aren’t already familiar with this small boot making family out of a small village in China, then maybe you aren’t actually the boot enthusiast you believe yourself to be. lol just kidding. But really, for anyone interested in high quality, beautifully built boots, Flame Panda is a brand worth looking into. Their main source of advertising and business is through their instagram @flamepanda11, which is run by their Peng. They're still a relatively small family owned business, but they’re following is growing exponentially (and for good reason).

I would go more into the background of their business and what they have to offer, but nothing I could write would compare to the information covered by Jake @almostvintagestyle on his blog: his review of his beautiful chunky monkey boots and an interview with Peng himself. So, if you’d like more background information on what Peng and Flame Panda have to offer, head over to his blog. Otherwise, on with the unboxing/review!

Ordering Process

As with most boot brands out of Asia lately, Flame Panda boots can be ordered via DM through his Instagram @flamepanda11. Unfortunately, there is no website or catalog listing all the patterns, leathers, or customization options he has available. Luckily Peng is very helpful and open to discussion regarding your MTO boots. He takes an active role in creating you the best boots possible, giving constructive input and suggestions rather than just mindlessly giving you whatever you ask for. Peng knows his materials and abilities best, and has a solid grasp on how to combine the two to create a quality product that meets both yours and his satisfaction.

The following are the exact details I requested regarding these black boots:

Model: 6 inch boots

Last: 181 last

Upper leather: black Maryam horsebutt

Upper stitching: black

Hardware: 5 copper eyelets, 2 quick hooks, 1 eyelet

Toe design: brogued cap toe, unstructured

Welt construction: 270° 2 row stitchdown (beige)

Lining: kangaroo

Midsole: single leather midsole

Edge finish: natural edge

Sole: black Dr. Sole half sole/heel

Heel design: incline curved

Sizing

For those of you who haven’t read my reviews before, my feet are stricken with large bunions on the pinky sides of my feet. As a result, picking shoe sizes have always been extremely difficult. (See my previous reviews for details). Below I’ve listed my sizes for all the other boot brands I own.

Thursdays - 10.5

Onderhoud - 45E

Benzein - 45E

Red Wing, Iron Ranger - 9.5EE

Truman Boot Company - 11EE

Viberg (1035 last) - 10.5

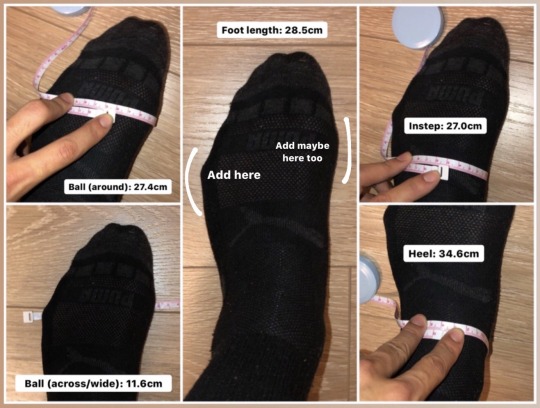

In trying to determine what size I would be in his boots, I sent Peng all the following images/information:

As many helpful measurements I could think, with images of how I took those measurements.

I also informed him that I wear this thick, memory foam orthotic in all my footwear.

And lastly, I provided him with a photo and the dimensions of the removable insole of another pair of boots that fit perfectly (in this case, my Onderhoud derbies). I also took photo of how my orthotic relates to these insoles, as well as a photo with my ugly foot. (TMI? Possibly. But I’d rather provide too much information than not enough, and it definitely paid off.)

Now that I think about it, I don't even know what size Peng ended up making for me. Regardless, these boots ended up fitting perfectly. This goes to show that Peng really knows what he’s doing, and can size you appropriately if given enough information.

Price & Shipping

For this particular boot in black Maryam horsebutt, Peng charged $685 USD including global shipping. I purchased these boots on 6/29/2020, and was quoted an unusually specific 95 day wait time. However, I didn't end up receiving these until 12/29/2020. While this is significantly longer than expected, Peng kept me up to date in his progress via Instagram DMs, so I never felt forgotten. (He told me that he and his family were moving locations during this time and production was running behind schedule. I didn’t mind, as I COVID was keeping me home majority of the time and didn’t have any reason to wear these boots anyway.) These days, I believe his wait time is closer to six months (which still really isn’t too bad for MTM boots).

Unboxing

Securely packaged, with tape as no object.

A box inside a box. A nice touch, actually. A lot of other boot companies simply ship the single boot box wrapped in butcher paper and tape, which often results in some minor box damage. In this case, the outer protective box took all the beating during transit, leaving the actual boot box in pristine condition. While this doesn’t have any affect on the quality of the boots themselves, it’s a good demonstration of the care and thought that Peng puts into all aspects of his products. He really holds himself to a higher standard, and I appreciate it.

Another reason to love Peng. He typically includes a small gift with every boot order! In this case, this nice little wallet.

In addition to the complementary thinner, cheaper single boot bags that most boot companies provide, Peng also included a larger canvas drawstring boot bag with a screen printed logo.

These boots came with three sets of laces. They were pre-laced with some standard width, flat, waxed cotton laces. Included in the box were two additional sets of laces: a pair of wider flat waxed cotton laces, and some round waxed cotton laces.

360 Degree View

Left boot:

Right boot:

Sole:

The Leather

The black Maryam horsebutt Peng used on these boots is absolutely gorgeous. The leather feels very substantial and hefty, and has a very nice sheen. The horsebutt also has a very subtle marbling and grain that shines through from certain angles. It’s a little difficult to capture in photos due to the deep black coloring of the leather, but you can take my word for it. These are incredible.

From what I’ve seen, I believe Peng is one of the best in the business when it comes to hide selection and clicking. He is extremely picky when determining what portions of each hide he actually uses on his boots. For instance, here is an example of him picking apart a hide, circling all the imperfections that he plans on excluding during clicking for boots.

youtube

This critical eye for detail increases Peng’s overhead considerably, as a significant portion of his leather is filtered out as unusable and unfit for boots. While this does increase the cost of his boots relative to other smaller boot brands coming out of Asia, it is also a big reason why the leather on his boots consistently break in and age so well. I have yet to see a pair of Flame Panda boots that have any unsightly creasing or loose grain, and I’m sure my pair will be no exception.

The 181 Last

Here’s a closer look at the tope shape of the 181 last. It’s got a nice almond toe shape without going overboard with pointy-ness. The outer sweep of the toe box has a more gradual, soft curve than the Onderhoud last, and even more so the Benzein Kujang last. It’s a clean and strong shape, with more of a sophisticated vibe than your typical work boot.

Outsole

Nice and clean outsole stitching by hand, with no overly wonky stitches.

The Liner

I chose to have this pair fully lined with a warm brown kangaroo leather. This makes the upper feel even more robust and structured (especially noticeable around the ankle/shaft of the boot), and gives them a bit more of a luxurious feel when on foot. (Also, note the half gusseted tongue. I highly prefer gusseted tongues over the standard floppy tongue. I specified during my order that I wanted a gusseted tongue, so I’m not 100% sure this tongue would come standard. Might be worth asking when/if you do order a pair for yourself.)

The Brogued Cap Toe

This is my first boot with a brogued cap toe. While I still think I prefer plain toes on my boots, I do like how this brogued cap looks here.

270 Degree Stitchdown Construction

Peng is probably most known for his 360° storm + embedded eversion welt. However, it is on the chunkier side, and I felt it would take away from the clean, sleeker look of this boot. Thus, I opted for double row stitchdown construction, which I think turned out quite nicely.

Peng’s welt stitching is very tight, parallel, and uniform, with a higher stitch count. Esthetically, I think it looks pretty similar to the 270° veldschoen stitching on my derbies from @renavgoodsco (seen at the 12 o’clock position below).

12 o’clock: Renav 270° veldschoen

2 o’clock: Truman 270° stitchdown

4 o’clock: Ostmo boots 270° custom welt stitching

6 o’clock: Benzein 270° veldschoen

8 o’clock: Role Club 270° flat welt

10 o’clock: Onderhoud 270° veldschoen

Inclined Curved Heel

If you haven’t been able to tell already, these are not the inclined curved heels (aka woodsman heels) that I had initially requested. While this is a pretty significant misstep on Peng’s end, I actually don’t mind too much. For low block heels, these appear to have been executed very cleanly, and it does complement the rest of the boot pattern quite nicely. If I had been dead set on having woodsman heels on these boots, I could see this being more of a dealbreaker.

Upper Stitching

Overall, the stitching on the upper is clean and tight, with a very uniform stitch count. There are a few spots where there are a few mis-stitches, which I will point out later. For now, here are a few macro shots to appreciate Peng’s stitch work.

One area on the upper where the stitching isn’t exactly perfect is along the left cap toe. As you can see below, there is one spot in the broguing pattern where it gets a little too close to the double row of stitches, and the thread actually tore into the brogue hole. Functional issue? No. But just something small I noticed.

A second spot that might be considered less than perfect is this stitching on the right boot, where the quarters meet the vamp. It looks like there may be an extra stitch in the vertical line extending beyond the horizontal stitch. This is seen on both the inside and outside quarters, and only on the right boot. (I included a pic of the stitching on the left boot a few photos back, where you can see the stitch lines come to a perfect T.) Again, this is being extremely nit-picky, and has no real bearing on the durability or quality of the boot itself.

A third and possibly the (relatively) biggest stitching imperfection was this loose thread on the front corner of the inside right quarter. It appears as though the end of the thread came out of the stitch hole. I later trimmed the loose thread and singed it with a lighter to prevent it from progressing, but there is still an empty stitch hole in the leather where the thread once was.

While we’re on the topic of imperfections, there is also a little bit of what appears to be black polish smeared along the brown welt of the right boot. Not a big issue, nor is it even a stitching or construction issue. Again, just thought I’d point it out to be thorough.

On Foot

First off, I would just like to praise Peng for absolutely nailing the fit of these boots. My feet are ugly and stupid, and sizing any footwear has always been a nightmare. However, using just the measurements and information I provided above (since getting measured in person was not an option), he still managed to build a perfectly fitting boot for my imperfectly shaped feet. I’ve worn them a few times now, and I’ve had zero pain whatsoever.

That being said, these boots are by far some of the stiffest boots I’ve ever worn—in a good way. I can tell these will require a good amount of wear to really break them in and have them relax and shape to my foot, but I’m looking forward to it. (Note, I’m in no way saying that this extended break in period will be at all painful; rather, just that it’ll take some time for the upper leather and sole to soften up.) These boots feel like tanks, and lacing these up make my feet feel invincible. I felt like Steph Curry wearing double ankle braces when I first tried walking in these, but the shafts are slowly starting to break in and roll with wear. The soles were also initially very rigid (like I was walking on planks of wood), but are beginning to flex more as I continue to wear these. Also note that I had these built on single leather midsoles! I can’t even imagine how stiff these would be if they had 1.5 or double layer midsoles (which are a quite popular request, from what I’ve seen on Peng’s Instagram).

Conclusions

I know it’s still early, but I can confidently say that these Flame Panda boots are one of the highest quality boots in my collection. They are definitely the most robust, and despite a few minor finishing issues, the level of cleanliness and finishing by Peng and his family is unmatched by the majority of boot makers worldwide (at least from what I’ve seen on Instagram). Other than maybe Goto-San of White Kloud (@show_goto), Peng is one of the best at not only sourcing beautiful leathers, but clicking as well. I have yet to see a pair of his boots with any unsightly creasing or grain, which gives me the confidence to recommend him to anyone who may be interested in purchasing a pair of these, or any of his other boot patterns.

I apologize if this has started to sound like a sponsored or endorsed advertisement, but I genuinely love these boots, and I believe Peng is a great dude who deserves the recognition he has been receiving lately. He is super generous and genuine, easy to talk to (albeit sometimes slow to respond, with the sheer volume of DMs he now receives), and is constantly striving to improve his materials and skills. And with a personality and passion like that, how could anyone not want to support him? These may have been my first pair of Flame Pandas, but they definitely aren't the last. (In fact, they’re already not. lol)

Anyway, hit me up via Instagram if you have any questions about Peng, Flame Panda, or anything else denim/boots related. Also, follow along over there to see how these stunning black Maryam horsebutt boots age with wear. I’m excited to see how they break in, and so should you. Ttfn!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Minor Problem

This is a fic I wrote once for the prompt a minor problem. I chose to make it about Laurent and Nikandros dealing with an injury and naturally they make it hilarious. I’m no writer, but I’ve always enjoyed this piece so I thought you guys might too.

...

It was within a warm evening and a nearby mingling crowd that Laurent sat huddled away in a cupboard clutching his shoulder. He knew he had been too ambitious today. A certain mood had seized him and he had been training harder than usual. Unlike ever before, however, there was no impending threat. Not even a theoretical threat he placed upon himself. He was not training to battle, but rather to integrate. Damen had been putting an admirable effort towards integration in Vere. Although Damen’s stubbornness had only allowed this effort to accomplish so much, Laurent knew from personal experience that this was truly his best. He felt the need to reciprocate. Just as Damen had struggled with some Veretian customs more than others when they had spent a month or so in Arles, there were particular Akielon traditions that bothered Laurent more than others. Athletics was one of the few he was genuinely interested in. So he felt that this was his chance to make a good impression. Unfortunately, his body had its limits. A fact Laurent had forgotten all too many times. He was new to this method of training and felt that his body was by now built differently than the Akielon soldiers who were raised swimming, wrestling, and throwing. So now he sat. Cramped and hiding in a pantry near the kitchens a floor below dinner. He was determined to make it there in time to eat with the others. So he had called for the obvious choice; the only person Laurent felt was right to help him. He waited in the dark, surrounded by the aroma of baked bread and endured throbbing pain. Surprisingly, he was patient in receiving his help.

Only a few moments after being summoned, Nikandros’ cleanly shaven black head appeared in the doorway wearing his usual stone-faced expression.

“Why are you in a cupboard?”

“I hurt myself.”

“That absolutely did not answer my question.”

“Sit down.”

Rather than ask any more questions, Nikandros took a skeptical look outside the door, inched his way inside and closed it behind him. He then clambered onto the ground.

“Do you want the long version or the short version?”

“What do you think.”

Laurent nodded. “I was training. By myself. As is customary.” Nikandros nodded back. “Included in my admittedly ambitious procedure was a handful of Akielon athletics.” He scoffed. “As you know, I am not yet skilled in the fine olympic art of the discus throw.”

“You’re pretty terrible.”

“So I fell. I fell wrong and dislocated my shoulder.”

Laurent hadn’t even finished his sentence before Nikandros dipped his head down to his knees and rubbed the sturdy bridge of his nose with his forefingers. “Are you joking?”

Golden eyebrows dropped. “Yes, Nikandros, this was just an excuse to get you to chat with me in the crowded dark surrounded by baked goods. You’re too evasive of my bonding tactics so this was my plan B. I’ve even brought tea.” Laurent motioned toward some spices on the top shelf in which some jars of loose leaf blends were hiding. Nikandros delivered the same dissatisfied expression to Laurent that he was receiving. He took a breath. They remained for a moment, almost in contest to see who was less satisfied with the other. In time, Nikandros seemed to take notice of how strongly Laurent had been holding back the pain in his shoulder and asked to take a look. He cursed in Akielon when he saw it and touched at the protruding bones lightly. “Does that hurt?” Laurent snapped without turning to look at him, “Of course it fucking hurts.”

Nikandros had only seemed to take notice of how Laurent was red, damp, and shaking from withstanding the pain in that moment. He showed genuine concern in his eyes. With dutiful urgency, he told Laurent to lay down. They exchanged looks, the one Laurent received was particularly criticizing, and realized they would really have to situate themselves carefully in order to lay Laurent’s body down and stretch his arm 90 degrees to the side. This was not Ios. It was not a large pantry. They had found a position in which Nikandros had to balance himself almost entirely over Laurent’s body, and received a lofty deal of death threats about losing his balance. Once they were settled, Nikandros held a pale wrist firmly in his sun tanned, callused hands.

“This is going to hurt.” He started. He was interrupted by “I know that.” “But-” he continued sourly, “if it hurts too much, tell me. I haven’t set back an enormous amount of shoulders in my day.”

“I’m sure your skills will suffice.” Laurent choked on his words as Nikandros began to pull his forearm outward. He moved carefully and slowly, bracing himself against Laurent’s torso for extra support. Laurent took quick deep breaths. He writhed his head around in a controlled chaos and stifled any noise from escaping his lips as Nikandros set his joint back in place. When the clap of the bones had been heard by the two of them, he relaxed his grip only slightly. He was waiting for Laurent to tell him that he was in less pain. His eyes partially welling up with tears, Laurent made eye contact, nodded fiercely, and tried to lift himself up on one of his elbows.

“Woah, woah,” Nikandros let go of Laurent’s injured arm but kept his hands outstretched as if to tell Laurent to lay back down. Laurent ripped himself up anyway and slapped one of Nikandros’ hands with his healthy one. Nikandros accepted the rejection and resituated himself as well. For a moment, they sat across from each other in silence. Laurent was still taking long deep breaths with his eyes closed. Nikandros was looking at him.

“Now put it in a sling.” He said.

Laurent was shaking his head.

“Make yourself a damn sling out of your chlamys right now, so help me god.”

Laurent was continuing to shake his head. He hadn’t opened his eyes.

“You won’t be able to use it at dinner.”

Laurent shrugged. “But I will.”

“You’re just as bad as him.”

Laurent jerked his head up to give Nikandros an offended look. It was well received. They continued to sit across from each other. Nikandros picked up a bread roll from a basket nearby. He gazed around the room and inhaled the scent of fresh grain as he tossed the roll into the air.

“Why did you drag me into a closet to relocate your injured shoulder and then refuse to wrap it? Is it pride? You don’t want all those kyroi to think you’re incompetent?”

Laurent shook his head.

“What then?”

“Him.”

Nikandros let a pause carry between them.

“What about him?”

Laurent rolled his head around and partially shrugged. He still hadn’t opened his eyes. He exhaled and seemed relaxed. “You know how he is. How we are. He’ll freak out.” A pause. “This is all because you’ll worry him?” Laurent shrugged almost too dismissively, like he might have given away that he didn’t want to dwell on this topic for too long. He couldn’t help but open his eyes. He found it too pressing to assess Nikandros’ reaction. He found that he had been caught by Nikandros, whose mouth had pulled into a smile. He was gazing at Laurent, but his gaze drifted away once it was met with blue. After a moment he said, “That’s pretty fuckin’ cute.” Laurent appreciated that. He actually did. Unlike the yes-man praise he often received on his relationship by so many of the political men he knew from court, hearing praise from Nikandros was different. It made him feel welcome. Almost like it had accomplished more in the integration aspect than any show of Akielon sportsmanship could.

“You truly don’t hesitate. Or ask questions before action. I appreciate that about you.” Laurent said. Nikandros shrugged. He was still tossing his roll into the air.

“I was about to have a nice dinner.”

“I was too.”

“Were you?”

A pause.

“Look, I’m trying to get you to that dinner as fast as possible.”

“After summoning me from halfway across the fort.”

“That’s in the past.”

“As is your injured shoulder.”

Laurent smiled. “As is my injured shoulder thanks to you.”

Nikandros helped him up. It took some effort. Laurent took some more deep breaths as he stabilized his posture. Nikandros held the doorknob and didn’t let Laurent leave before saying, “Look, I have to tell him. It’s kind of my job.”

“As the best friend, I suppose that’s only natural.”

Nikandros nodded. “But I swear I’ll make it sound minimal and resolved if you see Paschal after dinner.”

Laurent put a reassuring hand on his wrist, “It was my plan. Paschal can keep secrets.”

“I’m glad to hear it.”

Nikandros swung open the door and made sure there was no audience before speed walking away from it. Laurent, understanding his measure to be discreet, waited a moment before taking up his same direction at a more reserved speed.

#laurent of vere#prince laurent#nikandros#nikandros of delpha#laurent and nikandros#fic#captive prince#capri#captive prince fic#capri fic#my writing#lamen#laurent x damen#damen x laurent

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael Jarvis, "All in the Day's Work:” Cold War Doctoring and Its Discontents in William Burroughs's Naked Lunch, 35 Literature & Medicine 183 (2017)

Abstract

In Naked Lunch, the institutions and practices of science and medicine, specifically with regard to psychiatry/psychology, are symptoms of a bureaucratic system of control that shapes, constructs, defines, and makes procrustean alterations to both the mind and body of human subjects. Using sickness and junk (or heroin) as convenient metaphors for both a Cold War binary mentality and the mandatory consumption of twentieth-century capitalism, Burroughs presents modern man as fundamentally alienated from any sense of a personal self. Through policing the health of citizens, the doctors are some of the novel's most overt "Senders," or agents of capital-C Control, commodifying and exploiting the individual's humanity (mind and body) as a raw material in the generation of a knowledge that functions only in the legitimation and reinforcement of itself as authoritative.

The Man has a branch office in each of our brains, his corporate emblem is a white albatross, each local rep has a cover known as the Ego, and their mission in this world is Bad Shit. -- Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

William S. Burroughs's Naked Lunch (1959) is a mythological text, a cultural heritage that circulates socially and produces material effects without needing to be recognized in its actuality—without needing, that is, to be read. The very title conjures scenes of countercultural avant-garde low art, subversive precisely through its filthiness, an icon against which the idealized 1950s White Suburban Family archetype finds its definition, the abjection that establishes normativity. With regard to the book as a trope, Oliver Harris argues that, even before it was published, "an image of Naked Lunch would always precede the real thing and, for the image-hungry, replace it altogether."1 He however regards this relationship as symbiotic, mutually beneficial, and necessary for a critical appreciation of the novel's textual materiality and social function. For Elizabeth Wheeler, by contrast, the image has become the sole extant aspect, and what she portrays as essentially an irredeemably offensive work (which would of moral necessity be correct, if one truly considered the novel to be a glorification of violent rape and murder, as she seems to do) is now consumed only as "an index of the reader's hipness."2 While Wheeler's critique doesn't stem from the same "family values" conservative impulses motivating reviewers from the political Right (such as the movement to ban the book when it was published, or present-day reactions against what the book is supposed to "stand for"), she makes the same mistake of underestimating the critical work the novel does, stopping at the grotesque superficiality of the sadomasochistic revelry and taking Burroughs at his word when he asserts, "I have no secrets."3 In this paper I would like to work against both this type of criticism, inspired by Burroughs's "myth of transparency," and that of critics like Robin Lydenberg who, in privileging the author's textual practice over the book's content, ignore the novel's allegorical register in deference to formal practice in and of itself.4 Without attempting to re-theorize the entire body of Burroughs criticism, I would like to focus on the novel's portrayal of surgical and psychiatric practices and practitioners, and their regulatory role in what Michel Foucault calls "a strange scientifico-juridical complex," in order to move towards an understanding of the novel's larger concerns, macrocosmic sociopolitical interventions which don't stop at the micro-concerns of either drugs or mental illness.5

That is to say, in Naked Lunch, the institutions and practices of science and medicine, specifically with regard to the fields of surgery, psychiatry, and psychology, are symptoms of a bureaucratic system of control that shapes, constructs, defines, and makes procrustean alterations to both the mind and body of human subjects. Harris marks this as a manifestation of Cold War binaries and containment ideologies, noting that "the paranoid rhetoric of public health at risk from [sexual, ideological] contagion was especially potent, since the unspeakable and unnatural were figured as virtually undetectable, viral threats to the integrity of national and individual immune systems."6 Harris associates this with "what Andrew Ross calls 'the Cold War culture of germophobia.'"7 Using sickness and junk as convenient metaphors for the mandatory consumption of twentieth-century capitalism, Burroughs presents modern man as fundamentally alienated from any sense of an independent self. Through policing the health of citizens, the doctors are some of the novel's most overt "Senders," or agents of capital-C Control, commodifying and exploiting the individual's humanity (mind and body) as a raw material in the generation of a knowledge that functions only in the legitimation and reinforcement of itself as authoritative; or, as Burroughs makes clear in a macro-micro analogy of power which draws on the specific concern of heroin addiction, "sending can never be a means to anything but more sending, like junk."8

The novel's portrayal of the individual's relationship to systems of power, including the medical discipline, has been productively connected to the reigning intellectual discourse of the day, especially the critical social theory of the Frankfurt School. As Philip Walsh notes, Burroughs shares concerns with key Frankfurt theorists (Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse, among others) in that they "are all radical critics of certain trends of contemporary mass civilization," including the neoliberal devaluation of individual agency and the "proliferation of large-scale socially induced psychological pathology" by what Louis Althusser called Repressive State Apparatuses (RSAs), institutions such as the police, prisons, or the military, which are invested in violent control of individuals and populations.9

These thinkers join Burroughs (as I demonstrate below) in a belief that the contemporary emphasis on scientific discourse leads to an "instrumental rationality," or, a rationality in which the means justify an uninterrogated end, reducing the individual to a fungible cog in the greater social techno-bureaucratic corpus. The following discussion draws upon one Frankfurt-affiliate in particular, Erich Fromm, whose The Sane Society (1955) found popular success and made the author a household name (in certain circles, at least) during the period directly prior to and during the time Burroughs was writing the bulk of Naked Lunch.10 Fromm's relevance to a discussion of medical discourse in Burroughs goes further than mere contemporaneity, suggesting ways in which Cold War social pessimism found the imagery of pathologization and medical intervention especially resonant metonyms for the ways that the individual is both produced as a human subject and reduced in subjection to impersonal structures of domination.

To begin with the obvious regarding this imagery, Burroughs's depictions of medical spaces and practices are uniformly repulsive. While this is not in stark contrast to any of the novel's other tableaux of abjection, the representations of filth and incompetence in scenes of surgery and psychiatry are particularly striking. Dr. Benway, remembering a former job, recalls, "He gives me a job as ship's doctor on the S.S. Filariasis, as filthy a craft as ever sailed the seas. Operating with one hand, beating the rats offa my patient with the other and bedbugs and scorpions rain down from the ceiling" (28). The novel disrupts the medical image-narrative of order, cleanliness, and sterility by depicting hospital and operation scenes as kinetic, chaotic, and disgusting. In another scene, the aptly-named "Leif the Unlucky" finds himself in a Hieronymous Bosch-like hospital hellscape:

Then there was the time he collapsed with strangulated intestines, perforated ulcers and peritonitis in Cairo and the hospital was so crowded they bedded him in a latrine, and the Greek surgeon goofed and sewed up a live monkey in him, and he was gang-fucked by the Arab attendants, and one of the orderlies stole the penicillin and substituted Saniflush; and the time he got clap in his ass and a self-righteous English doctor cured him with an enema of hot sulphuric acid; and the German practitioner of Technological Medicine who removed his appendix with a rusty can opener and a pair of tin snips (he considered the germ theory "a nonsense").

The formal inertia of this passage presents the curative space as a domain of serial progressions along a negative continuum, where things can only go from bad to worse, either within the time of one visit, or throughout a lifetime of successive treatments. Because of the doctors' fundamental level of incompetence, outcomes range from brain damage to death, but are always alterations, if not annihilations, of the subject's humanity. This is coupled with a clear lack of accountability for members of the medical establishment. Benway, for example, keeps getting work, despite what must be a rather alarming resumé: "During my rather brief experience as a psychoanalyst … one patient ran amok in Grand Central with a flame thrower, two committed suicide and one died on the couch like a jungle rat (jungle rats are subject to die if confronted suddenly with a hopeless situation). So his relations beef and I tell them, 'It's all in the day's work.'"11 The psychoanalyst, tasked with bringing the patient back into line with normative society, produces violence and despair precisely through reducing the patient's options to arbitrary binary positions of sane/insane, normal/abnormal, and so on. These psychiatric narratives are the Cold War geopolitical polarization of "us/US vs. Them" reified and inscribed upon the body, meant to elide the individuated subject positions of patients; the practitioner's smug insouciance is more salt in the wound.

Regarding the larger categorical function of Control exemplified in Dr. Benway's role as diagnostician, Fromm notes in The Sane Society that the sane/insane binary is based on a "sociological relativism" which holds that "each society is normal inasmuch as it functions, and that pathology can be defined only in terms of the individual's lack of adjustment to the ways of life of his society"; however, if one were to postulate "universal criteria for mental health" based on a "normative humanism," then we would gain the ability to consider whether "the problem of mental health in a society is only that of the number of 'unadjusted' individuals, and not that of a possible unadjustment of culture itself."12 Fromm's overall discussion of this "pathology of normalcy" is useful in that he represents the fusion of several discourses in a manner similar to what we see in Burroughs—as a theoretician of the Frankfurt School as well as a clinical psychoanalyst, Fromm blends Freudianism and Marxism in a manner that smooths their jagged edges and resists the dogmatist's tendency towards treating them as totalizing discourse.13 An unfashionable humanism—like the almost pop-psychological emphasis on "Love" so often at the forefront of his thinking—undergirds his critique of industrial capital, and his belief in an a priori "natural" human condition provides an important platform from which to stage his critique and advocate for the political praxis of a "Humanistic Communitarian Socialism."14 As I will discuss below, Naked Lunch also relies on Marxist ideas of alienation and commodification in conjunction with Freudian libidinal drives, and the novel's exploration of alternatives to hegemonic binaries—the "either or, absolute terms" that never truly "correspond to what we know about the human nervous system and the physical world"—is likewise an attempt to theorize the individual's possibility for a more "natural" agency outside of interpellative discourses.15

Junk, for Burroughs, is not simply the object of an individual's addiction, but also a symbol of man's alienation from himself, and a device which positions him within commodity culture. Opiates, as opposed to other drugs, alter an individual's biochemistry at a fundamental level, leading to a "metabolic dependence" on the substance: "Morphine becomes a biologic need like water and the user may die if he is suddenly deprived of it. The diabetic will die without insulin, but he is not addicted to insulin. … He needs insulin to maintain a normal metabolism. The addict needs morphine to maintain a morphine metabolism, and so avoid the excruciatingly painful return to a normal metabolism."16 Use of the drug leads to not simply a desire for more of it (such as, for example, the function of lust or greed), but to an actual endocrinal transformation—the addict's body no longer functions as a human body, but is inducted into a separate junk economy. Using Slavoj Žižek's critique of consumer desire constituted through the symbolic order's always-withheld promise of "pure" pleasure, Ole Bjerg argues that the "complete satisfaction of desire experienced by the drug user in his high is at the same time a momentary cancellation of his desire. Together with the desire, his engagement in social reality, and thereby a fundamental part of what makes him a subject at all, also disappears."17 Indeed, the "addict exists in a painless, sexless, timeless state" as sedation erases the urgency of any Freudian drives;18 Benway speculates, "If all pleasure is relief from tension, junk affords relief from the whole life process, in disconnecting the hypothalamus, which is the center of psychic energy and libido" (30). Addiction to opiates results in a new or "other" life state for the user, one that Burroughs characterizes as vegetative.19

In the terms of Fromm's construction, this alternate state is alienation, and the "better-than-sex" high is, paradoxically, the opposite of happiness—not sadness, but "depression": "the inability to feel … the sense of being dead, while our body is alive."20 This understanding is tied to the user's place in capitalist culture—"It follows that happiness cannot be found in the state of inner passivity, and in the consumer attitude which pervades the life of alienated man"—a point which seems at odds with the countercultural anti-sociality of Burroughs's junkies.21 As a means of disconnecting the addict from the structures of society, the drug would seem to create marginal figures or outlaws, and to represent a potentially disordering force. Robert Holton notes the similarity of the junkie to David Riesman's "anomic," the "maladjusted," a "group including the misfits, the eccentrics, those who cannot fit in, and those who will not fit in, that assortment of individuals existing beyond—or perhaps beneath—the reach of adjusted conformity: drug addicts, sexual 'deviants,' criminals, the mentally ill, and so on."22 In Riesman's formulation, the maladjustment can be a deviation from the stable norm in either direction—the anomic could be a violent outlaw, or a passive catatonic. Holton suggests that "Burroughs' junkie bridges these opposites in his recourse to criminal behavior on one hand and his heroin-induced immobility on the other." Further, what both these poles share is the characteristic of "nonproductivity"; they are the waste products of society.23 Jason Morelyle likewise reads in Burroughs's trope of addiction "resources not simply for theorizing, but also for resisting control, especially in his representations of the so-called drug addict, a figure that is often understood as a subject formed at the limits of 'straight' society."24

While it is tempting to read the junkie as liberated, or "off the grid," the truth is much more complex. Not only do addicts fail to mobilize any sort of resistance to the dominant ideology, but heroin addiction functions to cyclically reintegrate the user back into the very economy that the high has liberated him from. Though, as Bjerg notes, the addict is perhaps able to evade the symbolic baggage of the established order of consumption through a "counterfeiting of the economy of desire," I would argue that the ideology of consumption as a negotiation of lack reaches its apotheosis in the subject's insatiable craving, and that the novel's representations of various addictions are all, as Lydenberg argues, "variations on a pattern of control and domination of the individual's will."25

Further, what critics have neglected to respond to is the important difference between this "junkie" (or opioid) model of addiction and the alternative models offered by other depictions of drug users and mentally disordered individuals. This key distinction may best be illustrated by Benway's ruminations in a scene where he "cures" schizophrenia by turning the patients into heroin addicts:

"A heart-warming sight," says Benway, "those junkies standing around waiting for the Man. Six months ago they were all schizophrenic. Some of them hadn't been out of bed for years. Now look at them. In all the course of my practices, I have never seen a schizophrenic junky, and junkies are mostly of the schizo physical type. …

"And why don't junkies get schizophrenia? Don't know yet. A schizophrenic can ignore hunger and starve to death if he isn't fed. No one can ignore heroin withdrawal. The fact of addiction imposes contact.

"But that's only one angle. Mescaline, LSD6, deteriorated adrenaline, harmine can produce an approximate schizophrenia. The best stuff is extracted from the blood of schizos; so schizophrenia is likely a drug psychosis. They got a metabolic connection, a Man Within you might say."

Schizophrenia is presented as an antisocial disorder here; by curing it through addiction to opiates, the doctor is attacking not the pathologized neurological condition but pathologized individuality and disconnection from consumer culture. By forcing the subjects to engage the junk networks of desire and consumption, the doctor circumvents the individual biological determination of the psychic state (the Man Within) and replaces it with himself, a stand-in for the Man, whose actions from the central position in the junk supply pyramid work to construct the social subject as an addict to an ideology of consumerism and powerlessness. The original (or schizophrenic's) Man Within, regardless of whether "his" effect on the subject is positive or negative, is disconnected from this economy of control. Therefore he must be superseded, denying an individual's mental or biological self-determination, in order to access the Control apparatus directly and reinsert the individual into the field of consumerism. In this sense, the "nonproductivity" of the anomic is of secondary importance, and arguments about the addict's "liminality" lose their force.26 Fromm notes that late capitalism "needs men who co-operate smoothly in large groups; who want to consume more and more, and whose tastes are standardized and can be easily influenced and anticipated," criteria which define Benway's drooling addicts precisely.27 Because of the automation of the means of production, it is less vital that the subject be a producer than an ever hungrier consumer, and heroin is at once a metaphor for and a reification of the control exerted on the subject by capitalist ideology. It is not, in any case, a vehicle for self-liberation.

Additionally, the bizarre reference to hallucinogenic drugs in the blood of schizophrenic subjects is telling, as they are substances that highlight the idiosyncrasies of the perception and experience of the individual, making them challenges to the pleasure, ease, and womb-like security of junk culture. These non-junk narcotics are defined by their widening of subjective experience, in direct opposition to the next-fix tunnel-vision of the opiate addict. Within the novel's ideological framework, we can think of these (LSD, mescaline, schizophrenia, etc.) in terms of their broadening horizontality. If the vertical hierarchies of power make the pyramid an apt metaphor for a junk/consumption addiction, these expansionist substances might be considered a part of the urban sprawl of consciousness.28 In contrast to the psychedelic magnification and opening up of subjectivity, the "relief from tension" provided by opiates is a release from the pain of being alive at all, a welcome dehumanization which imparts "to the organism some of the qualities of a plant."29

Historically, this need for escape into a thoughtless void would make sense as a way of dealing with anxieties and fears arising in part from the constant possibility of nuclear apocalypse. Writing from within what Alan Nadel calls "containment culture," Fromm notes:

Perhaps the most popular modern concept in the arsenal of psychiatric formulae is that of security. In recent years there is an increasing emphasis on the concept of security as the paramount aim of life, and as the essence of mental health. One reason for this attitude lies, perhaps, in the fact that the threat of war hanging over the world for many years has increased the longing for security. Another, more important reason, lies in the fact that people feel increasingly more insecure as the result of an increasing automatization and overconformity.30

Security, here, can be read as a desire for neutrality and normality, and additionally as a release from libidinal drives. Individuals trapped in the Manichaean binaries of Cold War ideology hope for a relief from the indirect tension of containment or the frightening bluster of brinksmanship, either through peace and disarmament or the complete elimination of the opposing superpower. On an individual level, "psychiatry and psychoanalysis have lent considerable support" to the growing segment of the population who "feel that they should have no doubts, no problems, that they should take no risks, and that they should always feel 'secure.'"31 This "security" is an abandoning of libidinal desire and the pursuit of human goals, and represents a fantasy of static certainty. Ultimately, argues Fromm, a thinking, rational human being can never attain complete security from the doubts and uncertainties which attend the complex functioning of the intellect and the passage of the individual through his own life. The real goal of mental health, he argues, "is not to feel secure, but to be able to tolerate insecurity without panic and undue fear."32 If we consider these ideas in terms of Burroughs's junkies, we see that through resorting to the sedation and dehumanization of the opiate high, the user aspires to this false ideal of security, a pursuit which results in the annihilation of the self and the exploitation of the individual by political and economic systems.

The work of the medical professionals in Naked Lunch similarly reflects this desire for security and an end to Cold War anxieties. As Jonathan Paul Eburne explains, the ubiquitous US/USSR sociopolitical binary view created a metonymic and associative bricolage of dread, comprised of "the fear of communism, the Bomb, homosexuality, sexual chaos and moral decrepitude, aliens (foreigners and extraterrestrials)" which were "condensed with nightmarish lucidity upon a unifying rhetorical figure"; in this case, a "festering and highly contagious disease" encroaching upon the national corpus.33 This macro-metaphor maps tellingly not only onto the real world paranoia and persecution of liminal subjectivities and peoples, but also onto the ways in which the novel's medical professionals view their role with regard to their wards. While the efforts of the doctors can be divided into two complementary camps (manipulation of the mind versus alteration of the body), their actions, whether in good faith or bad, all end in similar destructions of the "natural" or unassimilated individual, a pathologized state which needs a "cure."

To begin simply, we might examine the work of surgeons, and Burroughs's depictions of bizarre and counterintuitive alterations to the human body. In keeping with the "Leif the Unlucky" narrative, the surgeon is presented as hapless and error-prone, but there is an element of dark cheer and good intentions (unsurprisingly, paving the road to surgical hell). A German surgeon is prototypical in this sense: "Flushed with success he then began snipping and cutting out everything in sight: 'The human body is filled up vit unnecessitated parts. You can get by vit vone kidney. Vy have two? Yes dot is a kidney. … The inside parts should not be so close in together crowded. They need Lebensraum like the Vaterland'" (152). Surgery in Naked Lunch is based on arbitrary definitions of form and function, and designed to improve the design of the body by removing excess, in the service of a scientific "system which has no purpose and goal transcending it, and which makes man its appendix."34 "Doctor 'Fingers' Schaefer, the Lobotomy Kid" is the best example of the dangers of this type of medical idealism, as he desires, seemingly in good faith, the advance of humanity through alteration of or liberation from the individual's limiting physiognomy (87). His nicknames point to both a tactile manipulation of the patients' bodies and an outlaw, Wild West medical vigilantism. His aim is human betterment through efficiency; in one experiment, he argues that "the human nervous system can be reduced to a compact and abbreviated spinal column"—a rationalization of the excess of the individual. He dubs his creation "The Complete All American Deanxietized Man," signaling the lobotomizing psychiatric institution's misguided curative attempts regarding neuroses as well as the nationalist foundations of this type of discourse, and is shocked when the unveiled result is "a monster black centipede" (87). A courtroom scene presents the social and legislative backlash against these practices, charging him with the "unspeakable crime of brain rape … [;] forcible lobotomy": "He it is—he and no other—who has reduced whole provinces of our fair land to a state bordering on the far side of idiocy. … He it is who has filled great warehouses with row on row, tier on tier of helpless creatures who must have their every want attended. … 'The Drones' he calls them with a cynical leer of pure educated evil" (88–89). The ad hominem rhetoric against Schaefer is a reaction against the materiality of the lobotomy as a surgical practice, when it is, in fact, merely a reification of the ideological work performed by the psychiatric institution as a whole—Schaefer has attempted to give his patients the "security" they desire, and perhaps his only crime is that he has presented his creations to the public, and made the violent alteration and construction of the subject realizable in non-metaphorical terms through his actual cutting and stitching. Considered differently, in his construction of a vast brain-dead class of consumers, thus necessitating industrial production, bureaucratic management, and caretaking services, he might perhaps be lauded as a "job creator," that capitalist par excellence.

Benway is Schaefer's foil, and his prominent role in the text corresponds to the urgency of critiquing his work especially. Benway acts to construct his subjects psychologically, and his efforts recall Antonio Gramsci's concept of cultural hegemony, or Althusser's Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs), which assert themselves indirectly, and lack both overt violence and an identifiable central source. What his manipulation most resembles, however, is Gilles Deleuze's concept of the society of control, the biopolitical rationalization of large swaths of human capital that epitomizes post-industrial social order. While a Foucauldian disciplinary system initially imposes a physical order by delimiting the space available to the human body through "enclosures" (jail, walls, school, the factory), the society of control needs no such material infrastructure: "Enclosures are molds, distinct castings, but controls are a modulation, like a self-deforming cast that will continuously change from one moment to the other."35 This shift is necessary in a post-production economy, where movement and flow are the keys to encouraging consumption behaviors. The result is that the "operation of markets is now the instrument of social control. … Control is short-term and of rapid rates of turnover, but also continuous and without limit, while discipline was of long duration, infinite and discontinuous. Man is no longer man enclosed, but man in debt."36 The physical focus of discipline/enclosure gives way to the psychosocial manipulation of the consuming subject. Social order is enforced not through the penal code, but through naturalized economic imperatives combined with the data-mining of an Information Age bureaucracy.

Tellingly, then, Benway's tenure in Annexia sees the repeal or destruction of physically repressive laws and institutions:

"I deplore brutality," [Benway] said. "It's not efficient. On the other hand, prolonged mistreatment, short of physical violence, gives rise, when skillfully applied, to anxiety and a feeling of special guilt. … The subject must not realize that the mistreatment is a deliberate attack of an anti-human enemy on his personal identity. He must be made to feel that he deserves any treatment he receives because there is something (never specified) horribly wrong with him. The naked need of the control addicts must be decently covered by an arbitrary and intricate bureaucracy so that the subject cannot contact his enemy direct."

Reading like a crude burlesque of Kafka's The Trial, Benway's psychological experimentation is in the service of mind control, dismissing the use of torture as "puerile" and unsophisticated. It is Benway who speaks the oft-quoted line, "A functioning police state needs no police" (31, emphasis in original). Compare Benway's discussion of heroin and psychological conditioning to Fromm's analysis of the nature of control in the era of Cold War capitalism:

Authority in the middle of the twentieth century has changed its character; it is not overt authority, but anonymous, invisible, alienated authority. Nobody makes a demand, neither a person, nor an idea, nor a moral law. Yet we all conform as much or more than people in an intensely authoritarian society would. Indeed, nobody is an authority except "It." What is It? Profit, economic necessities, the market, common sense, public opinion, what "one" does, thinks, feels. The laws of anonymous authority are as invisible as the laws of the market—and just as unassailable. Who can attack the invisible? Who can rebel against Nobody?37

Like Benway's subjects, Fromm's modern individual is similarly beset by a sourceless, pervasive guilt, an anxiety that drives him to conform to anything whatsoever, at the cost of his individuality. Commenting on work like Benway's, he writes, "[T]he crowning achievement of manipulation is modern psychology. What Taylor did for industrial work, the psychologists do for the whole personality—all in the name of understanding and freedom. … [T]hese professions are in the process of becoming a serious danger to the development of man …; their practitioners are evolving into the priests of a new religion of fun, consumption and self-lessness, into the specialists of alienation, into the spokesmen for the alienated personality."38 Here, the individual is something compiled on an assembly line, put together piece by piece in accordance with a blueprint that he has no access to, becoming a subject only through being subjected to the mechanized hand of an invisible force. Psychiatry as an institution represents both the assembly-line worker who alters the psyche of the individual, and the "spokesmen" who make such manipulation acceptable to a public longing for the security provided by the quick fix.

The novel problematizes these public relations through the character of Benway, who produces overwhelmingly impaired subjects (identified by the label "Irreversible Neural Damage"), and casually absolves himself of any responsibility for his actions:

"Get these fucking INDs outa here. It's a bring down already. Bad for the tourist business."

"What should I do with them?"

"How in the fuck should I know? I'm a scientist. A pure scientist. Just get them outa here. I don't hafta look at them is all. They constitute an albatross."

…

Doctor Benway pauses at the door and looks back at the INDs.

"Our failures," he says. "Well, it's all in the day's work."

His concern is primarily with hiding the hideous results of his work from the gaze of public scrutiny represented by "the tourist business" (and likely also from the same legal institutions which have ensnared his colleague, Dr. Schaefer). Alluding to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" (1798), the failed results of Benway's experiments are "albatrosses," symbols that have reversed their aspect from positive to negative through one man's capricious violation of natural order, an excellent analogy for the minds/bodies of his medical subjects. Whether it's the law, the tourists, or relatives' "beef" Benway hides his failures from, there is on the one hand a recognition that he will be perceived negatively by the public, and simultaneously an utter disregard for the concerns of those outside his profession. Unlike the Mariner, Benway's albatrosses are shoved aside, out of sight; while the Mariner wears his sin around his neck for all to see, Benway's sins are worn, irreversibly, upon the bodies of his patients. More frightening than the summary absolution he allows himself with the phrase "it's all in the day's work" is the idea that each successive day will begin the process anew, as he labors unceasingly in his zealous devotion to anti-human techno-bureaucratic rationalities.

His insistence on the "purity" of both himself-as-scientist and science as an institution is an idealism that ignores the ends of experimentation (i.e., "albatrosses") in a valorization of experimentation for its own sake. Walsh reads Burroughs's focus on this type of self-invested scientism as explicating Max Weber's distinction between "substantive" and "instrumental" rationalities: while the former "involves critical questioning … in accordance with a concern with the ends or goals of life and human welfare," instrumental reason is associated with efficiency, a "means-oriented ethics," and "the increasing and unstoppable power of bureaucracies" which create "an unprecedented concentration of power among a technical elite."39 Benway's conception of his work as "pure" science epitomizes the instrumental rationality of any discursive system, medical or otherwise, that uses humanity as the raw materials to legitimize itself, or exerts arbitrary control over others. His hero is Doctor Tetrazzini, whose "operations were performances," "pure artistic creation … [where] the surgeon deliberately endangers his patient, and then, with incredible speed and celerity, rescues him from death at the last possible second" (51–52). Medical intervention has nothing to do with the actual circumstances of health, the patient, or the body, but is entirely self-contained, reflexive. Science/medicine confers upon itself an authority in perpetuity regardless of outcomes and without desire for advancement, based on constantly reinterpreted definitions of health and sickness, participating in experimentation for its own sake. Now, "deviant" or anomic citizens have become a ready pool of subjects for the extension of techno-capitalist mandates. The German doctor's darkly comic concern with affording enough "Lebensraum" to his patient's organs is doubly ironic: the literal meaning of the term is "living space," whereas the doctor's poorly reasoned intervention into the natural organization of the human body can only lead to death, regardless of the "space" created; further, the term unambiguously connects him to the Nazi party, not only in terms of its expansionist telos, but also in its extensive medical experimentation, crimes committed upon the bodies of Jews, homosexuals, and other "undesirable" elements who were imprisoned, surgically altered, sterilized, and euthanized, often in the name of disinterested "pure science" rather than outright hate. Burroughs's pointed inclusion of this character creates a direct connection between the contemporary surgical-psychiatric state and the horrors of the previous decade, as they share a similar nationalist rhetoric of disease and necessity; patients' bodies have become colonized territories, exploited in the name of security, normalization, and medical knowledge. As Harris notes in a discussion of the historical dimensions of Cold War binaries in Burroughs's earlier work Queer, "Both sides are acknowledged to be developing ultimate techniques of social control, and their economic and military applications. The era's defining political issue—the conflict between totalitarianism and individual freedom—no longer defines one side of the Cold War against the other"; rather, "they speak a common language of technological rationality and social engineering."40 Unlike the covert absent-presence of Nazi camps or Stalinist gulags, work like Dr. Benway's occurs almost in the open, becoming socially permissible as a result of Cold War "germophobia" and pathologization of the social (psychological, physical, sexual, political) Other. The novel points to the ways that the pervasive desire for security and dread of infiltration leads to unquestioning acceptance of a disciplinary psychological discourse that produces dehumanized, conforming subjects, hooked on literal junk or its counterpart in consumer ideology and the politics of fear.

Interestingly enough, Benway provides both the critiqued and the critiquing position with regard to the simultaneous epistemological and political roles of medicine/science in modern society. Reassuring Schaefer, who has expressed doubts about the morality of their work ("I can't escape a feeling … well, of evil about this"), he makes what amounts to a case for the aestheticization of science, a la Tetrazzini:

"Balderdash, my boy. … We're scientists. … Pure scientists. Disinterested research and damned be him who cries 'Hold, too much!' Such people are no better than party poops."

…

Schaefer is not listening. "You know," he says impulsively, "I think I'll go back to plain old-fashioned surgery. The human body is scandalously inefficient. Instead of a mouth and an anus to get out of order why not have one all-purpose hole to eat and eliminate? We could seal up nose and mouth, fill in the stomach, make an air hole direct into the lungs where it should have been in the first place. …"