#for context this was way back in 2017 when mary sues were still considered bad

Text

i think one of the funniest bad takes/criticisms ive ever seen about jack was that he’s somehow a Mary Sue because hurrdurr super powerful hurrdurr everyone loves him or whatever ??? like girl he’s suffering

#will come back to this eventually I promise#cal.txt#spn#jack kline#spn fandom#for context this was way back in 2017 when mary sues were still considered bad#and I think it was around the time 13x09 aired ? 08? whichever one the scorpion and the frog is#I think about it soo much like …. how can you be that wrong im sorry

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cigarettes: the pollution of modern-day society?

By Inge Rots

Many will recognize the anecdote or at least a variant of it, in which people would tell about how back in their younger days, no one would be surprised if, on a party, the host would offer its guests plenty of cigarettes, in the same amount as there would be snacks or beer. Or how, when driving all the way to Spain for vacation, it would be ‘totally normal’ that the father of a young family would smoke inside of the car, while leaving the windows closed. Or how, during class, the teacher would continue smoking while at the same time explaining the workings of the Pythagorean theorem, even though the room would be filled with young, healthy, and above all, innocent children.

These memories stand in sharp contrast with the contemporary relationship of society with cigarettes, that has evolved over time. Currently, several developments coming from various groups of interest, seem to sharpen the debate, both about the question of smoking behavior as an individual choice versus individuals as being exploited and made addicted by the large tobacco industries, as well as the tension between a liberal versus a more conservative approach. For instance, in the month of October, in the Netherlands the campaign of “Stoptober” is being launched, stimulating people to throw away their packs of cigarettes and start living a healthier, nicotine- and smoke-free life (NOS, 2018). This fits within a line of tendencies that focuses on a (moral) reconsideration of what is the best, optimal way of living a healthy, as well as a conscious, sustainable life in which responsibility not just for oneself, but also for one’s surroundings is taken into account.

What is more, since 2016, a large lobby against the tobacco industry, led by a well-known Dutch lawyer (De Volkskrant, 2018), is attempting to sue the big tobacco companies like Philip Morris from murder and attempted homicide, as they are claimed to be consciously making smokers addicted from an early age on, and in doing so, leave smokers without a real own voluntary choice in deciding whether or not to smoke. Rather, they are seen as ‘victims’ of the tobacco industry and should therefore be defended. Yet on the other hand, there is an increasing amount of local governments and campaigns throughout the Netherlands (as well as other countries) that is actively attempting to change smoking policies in public buildings, streets or entire cities, with the underlying aim of making smoking unacceptable and intolerable, in favor of all non-smokers. For example, the Rotterdam municipality wants to make the zone around its biggest hospital, Erasmus MC, smoke-free and with this, involve different institutions such as a high school as well in joining them (Morssinkhof, 2017). Moreover, the city of Groningen is actively attempting to shift the city into becoming even entirely smoke-free as a whole city. (NOS, 2018)

Particularly with the latter trend, the focus is shifting towards a further stigmatization, demonization and patronization of cigarette smoking, inclining towards the idea that smokers themselves are the ones to be blamed. This puts into question the tension between a more liberal versus a more conservative policy; should people be able to have freedom in making their own choices, or should their behavior be regulated? And how exactly are the boundaries within this tension divided? This will be further explored by viewing the phenomenon of smoking and smoking bans through the lens of structuralism.

The main idea of structuralism is that one can only understand something if the structure of relationships towards other elements that are relevant, is also taken into account and attempted to be understood, as only in their relationship towards one another, things will make sense. Thus, it is the structure that counts as meaningful in influencing how society perceives a particular phenomenon. As Cerulo’s (1998) study to newspaper reports on violence shows, it is not so much the content of the message that counts, but rather the context within which the message is presented, hence, the form or structure of the message, that influences the outcome and interpretation of the meaning. Speaking in McLuhan’s terms, “the medium is the message”. For instance, when media are reporting the news story about Rotterdam’s prospective smoking ban, initial differences in ‘sequencing’ could already be observed between different media organizations, resulting in differences in the emphasis on either people on the streets being interviewed about their opinion on the new smoking restrictions, or interviewing for instance the politicians behind the new policy, resulting in different interpretations that either emphasize the stigmatizing of smokers, or the banning of the tobacco industry.

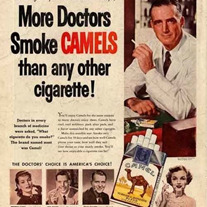

The way in which a society perceives its citizens’ smoking habits, hence, its perception, is a socially mediated mechanism, meaning that nothing one is confronted with can be viewed unprejudiced, as every scheme with which one views the world is based on prior experiences that form expectations of how to approach something new that comes on an individual’s path (Zerubavel, 1997). Hence, the mental lens with which one looks at and interprets the surrounding world, in an attempt to find patterns and categorize knowledge and information in such a way that it fits into our schemes (Douglas, 1990), one is always unconsciously influenced by the social background and context one is placed in (Zerubavel, 1997). For instance, this has (and is still being done) on a large scale by conscious advertising, but also by priming techniques in cinema and on television, that help normalize and stimulate the smoking of cigarettes. Castaldelli-Maia, Ventriglio and Bhugra (2015) explain how particularly in the twentieth century, cinema has played a relevant role in encouraging or even propagating smoking behavior through the direct association with smoking being ‘glamorous’ and luxury, even connecting cigarettes to prominent, classic cinema characters, and in doing so, making tobacco companies benefit greatly from this. It took only until the end of the previous century before it became clear how this promotion of cigarettes through advertising was part of a large-scale effort to hide the real damages of smoking on health (Castaldelli-Maia et al., 2015). In the US, an agreement on banning conscious smoking advertisements in cinema happened in the late nineties, reflecting a historical shift of mental lenses (Zerubavel, 1997), a shift from classifying smoking as normalized towards classifying it as ‘morally bad’. With more knowledge on the deteriorating effects of cigarettes on one’s health, steered and influenced by large developments in health science that are subject to socio-political changes, old facts were subject to a re-examination and re-interpretation, as the marker of a shift into the stigmatization of smoking (Zerubavel, 1997).

This new mental lens through which the majority of society now considers smoking behavior as something bad, favors the smoking bans that are rapidly increasing worldwide (Castaldelli-Maia et al., 2015). Yet, despite of the positive impact of this new legislation, it simultaneously targets the group of smokers with a feeling of being discriminated through a growing public stigma on their behavior, as it has now gained the status of being socially undesirable (Castaldelli-Maia et al., 2015). Yet, as has become clear, this should be considered as being relative and symbolic, since although there is a general agreement upon the idea that smoking is bad for one’s health, “what may be a stigmatizing characteristic in one era may not be in another” (Dovido, Major, & Crocker, 2000 as cited in Farrimond & Joffe, 2006, p. 482).

Nevertheless, although being symbolic, the consequences are not less real: Farrimond & Joffe (2006) show that stigmatization is even becoming bigger with the segregating of public spaces into smoking versus non-smoking areas. What is more, their study shows that non-smokers tend to classify smokers as ‘pollutive’, not only dirtying themselves with the toxic, unhealthy ingredients of cigarettes, but also polluting their environment and especially the non-smoking group of people around them (Farrimond & Joffe, 2006). This fits not only metaphorically, but also literally within Mary Douglas’ idea (1990) that our pollution behavior is a reaction towards anything that contradicts with the classifications within our mental scheme.

Lastly, a structuralist view on smoking behavior adheres to the binary opposition of the ‘good’ non-smokers versus the ‘bad’ smokers not only meaningfulness, as they could not exist without one another, but moreover, it reveals some kind of pollution power (Douglas, 1990) in which this division of society into ‘healthy’ (mostly dominated with middle-class) versus ‘unhealthy’ (not represented by middle-class) becomes a means of legitimizing dominance of this middle-class and thus, serves as a means to reinforce already existing power relations and reproduces a social inequality (Farrimond & Joffe, 2006). Yet, as Douglas mentions, pollutions are fortunately often remedied relatively simply, and the effects can be undone through certain rites, as could be seen with the introduction of the Stoptober campaign. And also, as one man on the street, interviewed by a reporting team argues, there is pollution in the air that we should be really worried about, hence, this said pollutive behavior by the smokers is in this light only relative and symbolic.

References

Castaldelli-Maia, J.M., Ventriglio, A., & Bhugra, D. (2016). Tobacco smoking: From ‘glamour’ to ‘stigma’. A comprehensive review. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 70, 24–33.

Cerulo, K. (1998). Deciphering violence: The cognitive structure of right and wrong. In: Lyn Spillman (ed.). Cultural sociology. Maiden, MA: Blackwell.

De Volkskrant. (2018, February 22). OM ziet geen mogelijkheid tabaksfabrikanten te vervolgen – Advocaat Ficq stapt naar gerechtshof. De Volkskrant. Retrieved from https://www.volkskrant.nl/wetenschap/om-ziet-geen-mogelijkheid-tabaksfabrikanten-te-vervolgen-advocaat-ficq-stapt-naar-gerechtshof~b3a9550a/

Douglas, M. (1990). Symbolic pollution. In: Jeffrey Alexander and Steven Seidman (Eds.). Culture and society: Contemporary debates. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Farrimond, H.R., & Joffe, H. (2006). Pollution, Peril and Poverty: A British Study of the Stigmatization of Smokers. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16, 481–491.

Morssinkhof, L. (2017, July 23). Groningen wil eerste rookvrije stad van Nederland worden. NOS. Retrieved from https://nos.nl/artikel/2184599-groningen-wil-eerste-rookvrije-stad-van-nederland-worden.html

NOS. (2018, August 3). Gaan we langzaam naar een compleet rookverbod? NOS. Retrieved from https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2244453-gaan-we-langzaam-naar-een-compleet-rookverbod.html

NOS. (2018, September 30). Verliefd geworden in Stoptoberhuis, maar stoppen met roken lukte niet. NOS. Retrieved from https://nos.nl/artikel/2252815-verliefd-geworden-in-stoptoberhuis-maar-stoppen-met-roken-lukte-niet.html

Zerubavel, E. (1997). Social mindscapes: An invitation to cognitive sociology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

0 notes

Text

How to Stay on the Right Side of the FTC When Publishing a Sponsored Video

The #Sponsored session at Advertising Week 2017 promised to shed light on the do’s, don’ts, and grey areas of #sponsored content “from multiple points of view.” And the panel discussion started off strongly.

Mary Orton, the style blogger behind Memorandum and the co-founder of Trove, a mobile style app, talked about how the updated FTC requirements have changed she discloses paid partnerships. Orton said she thought #ad and #sponsored are terms from another era and a different medium. The high profile influencer added that she only works with brands that she actually uses and often creates more content than an agreement calls for because she so passionate about the brand. Now, that promised to be a point of view that coulda been a contender.

Melissa Davis, the EVP of ShopStyle, the world’s most fashionable search engine, added her two cents on how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC.

Kim Waite, the VP Global Communications at Laura Mercier Cosmetics, disclosed how her brand has shifted traditional marketing and advertising budgets to influencer partnerships and discussed their stance on transparency and best practices.

But, then Ellie Altshuler, an attorney at Nixon Peabody, spoke. Altshuler, who specializes in influencer contracts, is the lead council for Digital Brand Architects. She discussed game-changing rulings and said the lines between influencers and celebrities are now more blurred than ever. Once she weighed in, the other three panelists deferred to her comments as if they were the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion (HiPPO).

So, what had promised to be a lively discussion “from multiple points of view,” turned into asymmetrical conversation with more than one panelist asking at one point or another, “What do you think, Ellie?” Nevertheless, video marketers still need to know if “Sponsored is a dirty word or new normal. So, let me summarize what Altshuler had to say about how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC.

If you have any influence over influencers, alert them to three developments, including the FTC’s first law enforcement action against individual online influencers for their role in misleading practices. According to the FTC, Trevor Martin and Thomas Cassell – known on their YouTube channels as TmarTn and Syndicate – deceptively endorsed the online gambling site CSGO Lotto without disclosing that they owned the company.

Download Our New Sponsored Video Insights Report Today! Get All the Latest Data on Sponsored Video Trends

FTC & Law Enforcement

Here’s the backstory: Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (also known as CS: GO) is an online, multiplayer, first-person shooter game. “Skins” are game collectibles that can be bought, sold, or traded for real money. Skins have another use: They can be used as virtual currency on certain gambling sites, including CSGOLotto.com. On that site, players could challenge others to a one-on-one coin flip, wagering their pooled skins. In 2015, respondent Martin posted a video touting CSGO Lotto:

We found this new site called CSGO Lotto, so I’ll link it down in the description if you guys want to check it out. But we were betting on it today and I won a pot of like $69 or something like that so it was a pretty small pot but it was like the coolest feeling ever. And I ended up like following them on Twitter and stuff and they hit me up. And they’re like talking to me about potentially doing like a skins sponsorship like they’ll give me skins to be able to bet on the site and stuff. And I’ve been like considering doing it.

Martin followed up with more videos on his YouTube channel showing him gambling on the CSGO Lotto site. In addition, he tweeted things like “Made $13k in about 5 minutes on CSGO betting. Absolutely insane” and posted on Instagram “Unreal!! Won two back to back CSGOLotto games today on stream – $13,000 in total winnings.”

Cassell promoted CSGO Lotto in a similar way, posting videos that were viewed more than five million times. In addition, he tweeted a screen shot of himself winning a betting pool worth over $2,100 with the caption “Not a bad way to start the day!” According to another tweet, “I lied . . . I didn’t turn $200 into $4,000 on @CSGOLotto. . . I turned it into $6,000!!!!” Then there’s this one: “Bruh.. i’ve won like $8,000 worth of CS:GO Skins today on @CSGOLotto. I cannot even believe it!”

Well, Bruhs, while we’re on the subject of things we cannot even believe, did either of you like consider clearly disclosing that you like owned the company – a material connection requiring disclosure under FTC law?

The complaint also challenges how the respondents ran their own influencer program for CSGO Lotto. They paid other gamers between $2,500 and $55,000 in cash or skins “to post in their social media circles about their experiences in using” the gambling site. However, the contract made clear that those influencers couldn’t make “statements, claims, or representations . . . that would impair the name, reputation and goodwill” of CSGO Lotto. And post they did on YouTube, Twitch, Twitter, and Facebook – in many instances, touting winnings worth thousands of dollars.

According to the FTC, Cassell, Martin, and CSGOLotto, Inc. falsely claimed that their videos and social media posts – and the videos and posts of the influencers they hired – reflected the independent opinions of impartial users. The complaint also charges that the respondents failed to disclose the material connection they had to the company – and the connection their paid influencers had. The proposed settlement requires Cassell, Martin, and the company to make those disclosures clearly and conspicuously in the future. The FTC is accepting public comments about the settlement until October 10, 2017.

An interesting aside: This isn’t the first time Cassell’s name has appeared in an FTC complaint. In a 2015 settlement with Machinima, the FTC alleged that Cassell pocketed $30,000 for two video reviews of Xbox One that he uploaded to his YouTube channel. Although the FTC didn’t sue him, the complaint in that case alleged, “Nowhere in the videos or in the videos’ descriptions did Cassell disclose that Respondent paid him to create and upload them.”

FTC: Warning Letters

The next development of interest to influencers relates to more than 90 educational letters the FTC sent to influencers and brands in April 2017, reminding them that, if influencers are endorsing a brand and have a “material connection” to the marketer, that relationship must be clearly disclosed, unless the connection is already clear from the context of the endorsement.

21 of the influencers who got the April letter just received a follow-up warning letter, citing specific social media posts the FTC staff is concerned might not be in compliance with the FTC’s Endorsement Guides. But the letters are different this time. The latest round asks the recipients to let the FTC know if they have material connections to the brands in the identified social media posts. If they do, the FTC has asked them to spell out the steps they will be taking to make sure they clearly disclose their material connections to brands and businesses.

Updated Guidance for Influencers and Marketers

The FTC has also just released an updated version of The FTC’s Endorsement Guides: What People are Asking, a staff publication that answers questions about the use of endorsements, including in social media. The principles remain the same, but we’ve answered more than 20 new questions relevant to influencers and marketers on topics like tags in pictures, disclosures in Snapchat and Instagram, the use of hashtags, and disclosure tools built into some platforms. You’ll want to read the updated brochure for details, but here are four “heads up” points for influencers:

Clearly disclose when you have a financial or family relationship with a brand. “But everybody knows!” No, they don’t. It’s unwise for influencers to assume that people know all about their business relationships.

Don’t assume that using a platform’s disclosure tool is sufficient. Some platforms are starting to offer disclosure tools, but that’s no guarantee they’re an effective way for an influencer to disclose a material connection to a brand. Like so many things on social media, it’s all about context. One key consideration is placement – whether the disclosure attracts viewers’ attention, taking into account where people are likely to look on a particular platform. For example, when paging through a stream of eye-catching photos, a viewer may not spot a disclosure placed above the picture or off to the side. The ultimate responsibility for making clear disclosures is yours. That’s why you want to make sure your disclosures are hard to miss.

Avoid ambiguous disclosures like #thanks, #collab, #sp, #spon, or #ambassador. Clarity counts. When disclosing a material connection to a brand, use language that’s clear and unmistakable. It’s unlikely that abbreviations, shorthand, or arcane lingo will communicate the disclosure effectively to consumers. Think of it like football. Unless the quarterback throws the ball and the receiver catches it, it’s an incomplete pass.

Don’t rely on a disclosure placed after a CLICK MORE link or in another easy-to-miss location. Consider your own viewing habits on social media. Do you click every CLICK MORE link? We don’t either. When disclosing a brand relationship, the better approach is to hit ‘em right between the eyes. Furthermore, on image-only platforms, superimpose your disclosure over the picture in a clear font that contrasts sharply with the background.

Now, I’m not a lawyer. But, I know enough to recommend that you talk with one about how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC. That’s right, I would have differed to the HiPPO, too. Hey, there are plenty of other things worth debating.

How to Stay on the Right Side of the FTC When Publishing a Sponsored Video was originally posted by Video And Digital Marketing Tips

0 notes

Text

How to Stay on the Right Side of the FTC When Publishing a Sponsored Video

The #Sponsored session at Advertising Week 2017 promised to shed light on the do’s, don’ts, and grey areas of #sponsored content “from multiple points of view.” And the panel discussion started off strongly.

Mary Orton, the style blogger behind Memorandum and the co-founder of Trove, a mobile style app, talked about how the updated FTC requirements have changed she discloses paid partnerships. Orton said she thought #ad and #sponsored are terms from another era and a different medium. The high profile influencer added that she only works with brands that she actually uses and often creates more content than an agreement calls for because she so passionate about the brand. Now, that promised to be a point of view that coulda been a contender.

Melissa Davis, the EVP of ShopStyle, the world’s most fashionable search engine, added her two cents on how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC.

Kim Waite, the VP Global Communications at Laura Mercier Cosmetics, disclosed how her brand has shifted traditional marketing and advertising budgets to influencer partnerships and discussed their stance on transparency and best practices.

But, then Ellie Altshuler, an attorney at Nixon Peabody, spoke. Altshuler, who specializes in influencer contracts, is the lead council for Digital Brand Architects. She discussed game-changing rulings and said the lines between influencers and celebrities are now more blurred than ever. Once she weighed in, the other three panelists deferred to her comments as if they were the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion (HiPPO).

So, what had promised to be a lively discussion “from multiple points of view,” turned into asymmetrical conversation with more than one panelist asking at one point or another, “What do you think, Ellie?” Nevertheless, video marketers still need to know if “Sponsored is a dirty word or new normal. So, let me summarize what Altshuler had to say about how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC.

If you have any influence over influencers, alert them to three developments, including the FTC’s first law enforcement action against individual online influencers for their role in misleading practices. According to the FTC, Trevor Martin and Thomas Cassell – known on their YouTube channels as TmarTn and Syndicate – deceptively endorsed the online gambling site CSGO Lotto without disclosing that they owned the company.

Download Our New Sponsored Video Insights Report Today! Get All the Latest Data on Sponsored Video Trends

FTC & Law Enforcement

Here’s the backstory: Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (also known as CS: GO) is an online, multiplayer, first-person shooter game. “Skins” are game collectibles that can be bought, sold, or traded for real money. Skins have another use: They can be used as virtual currency on certain gambling sites, including CSGOLotto.com. On that site, players could challenge others to a one-on-one coin flip, wagering their pooled skins. In 2015, respondent Martin posted a video touting CSGO Lotto:

We found this new site called CSGO Lotto, so I’ll link it down in the description if you guys want to check it out. But we were betting on it today and I won a pot of like $69 or something like that so it was a pretty small pot but it was like the coolest feeling ever. And I ended up like following them on Twitter and stuff and they hit me up. And they’re like talking to me about potentially doing like a skins sponsorship like they’ll give me skins to be able to bet on the site and stuff. And I’ve been like considering doing it.

Martin followed up with more videos on his YouTube channel showing him gambling on the CSGO Lotto site. In addition, he tweeted things like “Made $13k in about 5 minutes on CSGO betting. Absolutely insane” and posted on Instagram “Unreal!! Won two back to back CSGOLotto games today on stream – $13,000 in total winnings.”

Cassell promoted CSGO Lotto in a similar way, posting videos that were viewed more than five million times. In addition, he tweeted a screen shot of himself winning a betting pool worth over $2,100 with the caption “Not a bad way to start the day!” According to another tweet, “I lied … I didn’t turn $200 into $4,000 on @CSGOLotto… I turned it into $6,000!!!!” Then there’s this one: “Bruh.. i’ve won like $8,000 worth of CS:GO Skins today on @CSGOLotto. I cannot even believe it!”

Well, Bruhs, while we’re on the subject of things we cannot even believe, did either of you like consider clearly disclosing that you like owned the company – a material connection requiring disclosure under FTC law?

The complaint also challenges how the respondents ran their own influencer program for CSGO Lotto. They paid other gamers between $2,500 and $55,000 in cash or skins “to post in their social media circles about their experiences in using” the gambling site. However, the contract made clear that those influencers couldn’t make “statements, claims, or representations … that would impair the name, reputation and goodwill” of CSGO Lotto. And post they did on YouTube, Twitch, Twitter, and Facebook – in many instances, touting winnings worth thousands of dollars.

According to the FTC, Cassell, Martin, and CSGOLotto, Inc. falsely claimed that their videos and social media posts – and the videos and posts of the influencers they hired – reflected the independent opinions of impartial users. The complaint also charges that the respondents failed to disclose the material connection they had to the company – and the connection their paid influencers had. The proposed settlement requires Cassell, Martin, and the company to make those disclosures clearly and conspicuously in the future. The FTC is accepting public comments about the settlement until October 10, 2017.

An interesting aside: This isn’t the first time Cassell’s name has appeared in an FTC complaint. In a 2015 settlement with Machinima, the FTC alleged that Cassell pocketed $30,000 for two video reviews of Xbox One that he uploaded to his YouTube channel. Although the FTC didn’t sue him, the complaint in that case alleged, “Nowhere in the videos or in the videos’ descriptions did Cassell disclose that Respondent paid him to create and upload them.”

FTC: Warning Letters

The next development of interest to influencers relates to more than 90 educational letters the FTC sent to influencers and brands in April 2017, reminding them that, if influencers are endorsing a brand and have a “material connection” to the marketer, that relationship must be clearly disclosed, unless the connection is already clear from the context of the endorsement.

21 of the influencers who got the April letter just received a follow-up warning letter, citing specific social media posts the FTC staff is concerned might not be in compliance with the FTC’s Endorsement Guides. But the letters are different this time. The latest round asks the recipients to let the FTC know if they have material connections to the brands in the identified social media posts. If they do, the FTC has asked them to spell out the steps they will be taking to make sure they clearly disclose their material connections to brands and businesses.

Updated Guidance for Influencers and Marketers

The FTC has also just released an updated version of The FTC’s Endorsement Guides: What People are Asking, a staff publication that answers questions about the use of endorsements, including in social media. The principles remain the same, but we’ve answered more than 20 new questions relevant to influencers and marketers on topics like tags in pictures, disclosures in Snapchat and Instagram, the use of hashtags, and disclosure tools built into some platforms. You’ll want to read the updated brochure for details, but here are four “heads up” points for influencers:

Clearly disclose when you have a financial or family relationship with a brand. “But everybody knows!” No, they don’t. It’s unwise for influencers to assume that people know all about their business relationships.

Don’t assume that using a platform’s disclosure tool is sufficient. Some platforms are starting to offer disclosure tools, but that’s no guarantee they’re an effective way for an influencer to disclose a material connection to a brand. Like so many things on social media, it’s all about context. One key consideration is placement – whether the disclosure attracts viewers’ attention, taking into account where people are likely to look on a particular platform. For example, when paging through a stream of eye-catching photos, a viewer may not spot a disclosure placed above the picture or off to the side. The ultimate responsibility for making clear disclosures is yours. That’s why you want to make sure your disclosures are hard to miss.

Avoid ambiguous disclosures like #thanks, #collab, #sp, #spon, or #ambassador. Clarity counts. When disclosing a material connection to a brand, use language that’s clear and unmistakable. It’s unlikely that abbreviations, shorthand, or arcane lingo will communicate the disclosure effectively to consumers. Think of it like football. Unless the quarterback throws the ball and the receiver catches it, it’s an incomplete pass.

Don’t rely on a disclosure placed after a CLICK MORE link or in another easy-to-miss location. Consider your own viewing habits on social media. Do you click every CLICK MORE link? We don’t either. When disclosing a brand relationship, the better approach is to hit ‘em right between the eyes. Furthermore, on image-only platforms, superimpose your disclosure over the picture in a clear font that contrasts sharply with the background.

Now, I’m not a lawyer. But, I know enough to recommend that you talk with one about how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC. That’s right, I would have differed to the HiPPO, too. Hey, there are plenty of other things worth debating.

0 notes

Text

How to Stay on the Right Side of the FTC When Publishing a Sponsored Video

The #Sponsored session at Advertising Week 2017 promised to shed light on the do’s, don’ts, and grey areas of #sponsored content “from multiple points of view.” And the panel discussion started off strongly.

Mary Orton, the style blogger behind Memorandum and the co-founder of Trove, a mobile style app, talked about how the updated FTC requirements have changed she discloses paid partnerships. Orton said she thought #ad and #sponsored are terms from another era and a different medium. The high profile influencer added that she only works with brands that she actually uses and often creates more content than an agreement calls for because she so passionate about the brand. Now, that promised to be a point of view that coulda been a contender.

Melissa Davis, the EVP of ShopStyle, the world’s most fashionable search engine, added her two cents on how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC.

Kim Waite, the VP Global Communications at Laura Mercier Cosmetics, disclosed how her brand has shifted traditional marketing and advertising budgets to influencer partnerships and discussed their stance on transparency and best practices.

But, then Ellie Altshuler, an attorney at Nixon Peabody, spoke. Altshuler, who specializes in influencer contracts, is the lead council for Digital Brand Architects. She discussed game-changing rulings and said the lines between influencers and celebrities are now more blurred than ever. Once she weighed in, the other three panelists deferred to her comments as if they were the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion (HiPPO).

So, what had promised to be a lively discussion “from multiple points of view,” turned into asymmetrical conversation with more than one panelist asking at one point or another, “What do you think, Ellie?” Nevertheless, video marketers still need to know if “Sponsored is a dirty word or new normal. So, let me summarize what Altshuler had to say about how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC.

If you have any influence over influencers, alert them to three developments, including the FTC’s first law enforcement action against individual online influencers for their role in misleading practices. According to the FTC, Trevor Martin and Thomas Cassell – known on their YouTube channels as TmarTn and Syndicate – deceptively endorsed the online gambling site CSGO Lotto without disclosing that they owned the company.

Download Our New Sponsored Video Insights Report Today! Get All the Latest Data on Sponsored Video Trends

FTC & Law Enforcement

Here’s the backstory: Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (also known as CS: GO) is an online, multiplayer, first-person shooter game. “Skins” are game collectibles that can be bought, sold, or traded for real money. Skins have another use: They can be used as virtual currency on certain gambling sites, including CSGOLotto.com. On that site, players could challenge others to a one-on-one coin flip, wagering their pooled skins. In 2015, respondent Martin posted a video touting CSGO Lotto:

We found this new site called CSGO Lotto, so I’ll link it down in the description if you guys want to check it out. But we were betting on it today and I won a pot of like $69 or something like that so it was a pretty small pot but it was like the coolest feeling ever. And I ended up like following them on Twitter and stuff and they hit me up. And they’re like talking to me about potentially doing like a skins sponsorship like they’ll give me skins to be able to bet on the site and stuff. And I’ve been like considering doing it.

Martin followed up with more videos on his YouTube channel showing him gambling on the CSGO Lotto site. In addition, he tweeted things like “Made $13k in about 5 minutes on CSGO betting. Absolutely insane” and posted on Instagram “Unreal!! Won two back to back CSGOLotto games today on stream – $13,000 in total winnings.”

Cassell promoted CSGO Lotto in a similar way, posting videos that were viewed more than five million times. In addition, he tweeted a screen shot of himself winning a betting pool worth over $2,100 with the caption “Not a bad way to start the day!” According to another tweet, “I lied . . . I didn’t turn $200 into $4,000 on @CSGOLotto. . . I turned it into $6,000!!!!” Then there’s this one: “Bruh.. i’ve won like $8,000 worth of CS:GO Skins today on @CSGOLotto. I cannot even believe it!”

Well, Bruhs, while we’re on the subject of things we cannot even believe, did either of you like consider clearly disclosing that you like owned the company – a material connection requiring disclosure under FTC law?

The complaint also challenges how the respondents ran their own influencer program for CSGO Lotto. They paid other gamers between $2,500 and $55,000 in cash or skins “to post in their social media circles about their experiences in using” the gambling site. However, the contract made clear that those influencers couldn’t make “statements, claims, or representations . . . that would impair the name, reputation and goodwill” of CSGO Lotto. And post they did on YouTube, Twitch, Twitter, and Facebook – in many instances, touting winnings worth thousands of dollars.

According to the FTC, Cassell, Martin, and CSGOLotto, Inc. falsely claimed that their videos and social media posts – and the videos and posts of the influencers they hired – reflected the independent opinions of impartial users. The complaint also charges that the respondents failed to disclose the material connection they had to the company – and the connection their paid influencers had. The proposed settlement requires Cassell, Martin, and the company to make those disclosures clearly and conspicuously in the future. The FTC is accepting public comments about the settlement until October 10, 2017.

An interesting aside: This isn’t the first time Cassell’s name has appeared in an FTC complaint. In a 2015 settlement with Machinima, the FTC alleged that Cassell pocketed $30,000 for two video reviews of Xbox One that he uploaded to his YouTube channel. Although the FTC didn’t sue him, the complaint in that case alleged, “Nowhere in the videos or in the videos’ descriptions did Cassell disclose that Respondent paid him to create and upload them.”

FTC: Warning Letters

The next development of interest to influencers relates to more than 90 educational letters the FTC sent to influencers and brands in April 2017, reminding them that, if influencers are endorsing a brand and have a “material connection” to the marketer, that relationship must be clearly disclosed, unless the connection is already clear from the context of the endorsement.

21 of the influencers who got the April letter just received a follow-up warning letter, citing specific social media posts the FTC staff is concerned might not be in compliance with the FTC’s Endorsement Guides. But the letters are different this time. The latest round asks the recipients to let the FTC know if they have material connections to the brands in the identified social media posts. If they do, the FTC has asked them to spell out the steps they will be taking to make sure they clearly disclose their material connections to brands and businesses.

Updated Guidance for Influencers and Marketers

The FTC has also just released an updated version of The FTC’s Endorsement Guides: What People are Asking, a staff publication that answers questions about the use of endorsements, including in social media. The principles remain the same, but we’ve answered more than 20 new questions relevant to influencers and marketers on topics like tags in pictures, disclosures in Snapchat and Instagram, the use of hashtags, and disclosure tools built into some platforms. You’ll want to read the updated brochure for details, but here are four “heads up” points for influencers:

Clearly disclose when you have a financial or family relationship with a brand. “But everybody knows!” No, they don’t. It’s unwise for influencers to assume that people know all about their business relationships.

Don’t assume that using a platform’s disclosure tool is sufficient. Some platforms are starting to offer disclosure tools, but that’s no guarantee they’re an effective way for an influencer to disclose a material connection to a brand. Like so many things on social media, it’s all about context. One key consideration is placement – whether the disclosure attracts viewers’ attention, taking into account where people are likely to look on a particular platform. For example, when paging through a stream of eye-catching photos, a viewer may not spot a disclosure placed above the picture or off to the side. The ultimate responsibility for making clear disclosures is yours. That’s why you want to make sure your disclosures are hard to miss.

Avoid ambiguous disclosures like #thanks, #collab, #sp, #spon, or #ambassador. Clarity counts. When disclosing a material connection to a brand, use language that’s clear and unmistakable. It’s unlikely that abbreviations, shorthand, or arcane lingo will communicate the disclosure effectively to consumers. Think of it like football. Unless the quarterback throws the ball and the receiver catches it, it’s an incomplete pass.

Don’t rely on a disclosure placed after a CLICK MORE link or in another easy-to-miss location. Consider your own viewing habits on social media. Do you click every CLICK MORE link? We don’t either. When disclosing a brand relationship, the better approach is to hit ‘em right between the eyes. Furthermore, on image-only platforms, superimpose your disclosure over the picture in a clear font that contrasts sharply with the background.

Now, I’m not a lawyer. But, I know enough to recommend that you talk with one about how to be successful, creative, and remain authentic while working within the guidelines of the FTC. That’s right, I would have differed to the HiPPO, too. Hey, there are plenty of other things worth debating.

0 notes