#fang lijun

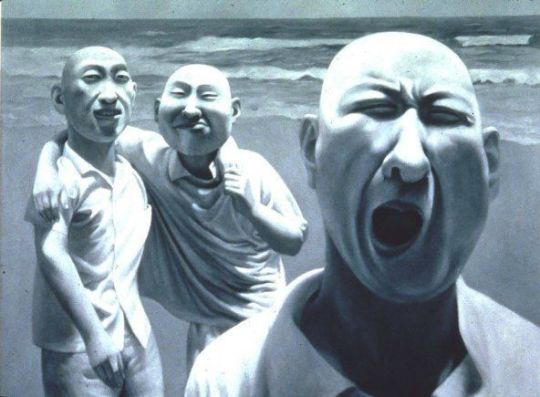

Photo

Fang Lijun (Chinese, 1963), 2001.8.20, 2001. Acrylic on canvas, 91 x 60.5 cm.

505 notes

·

View notes

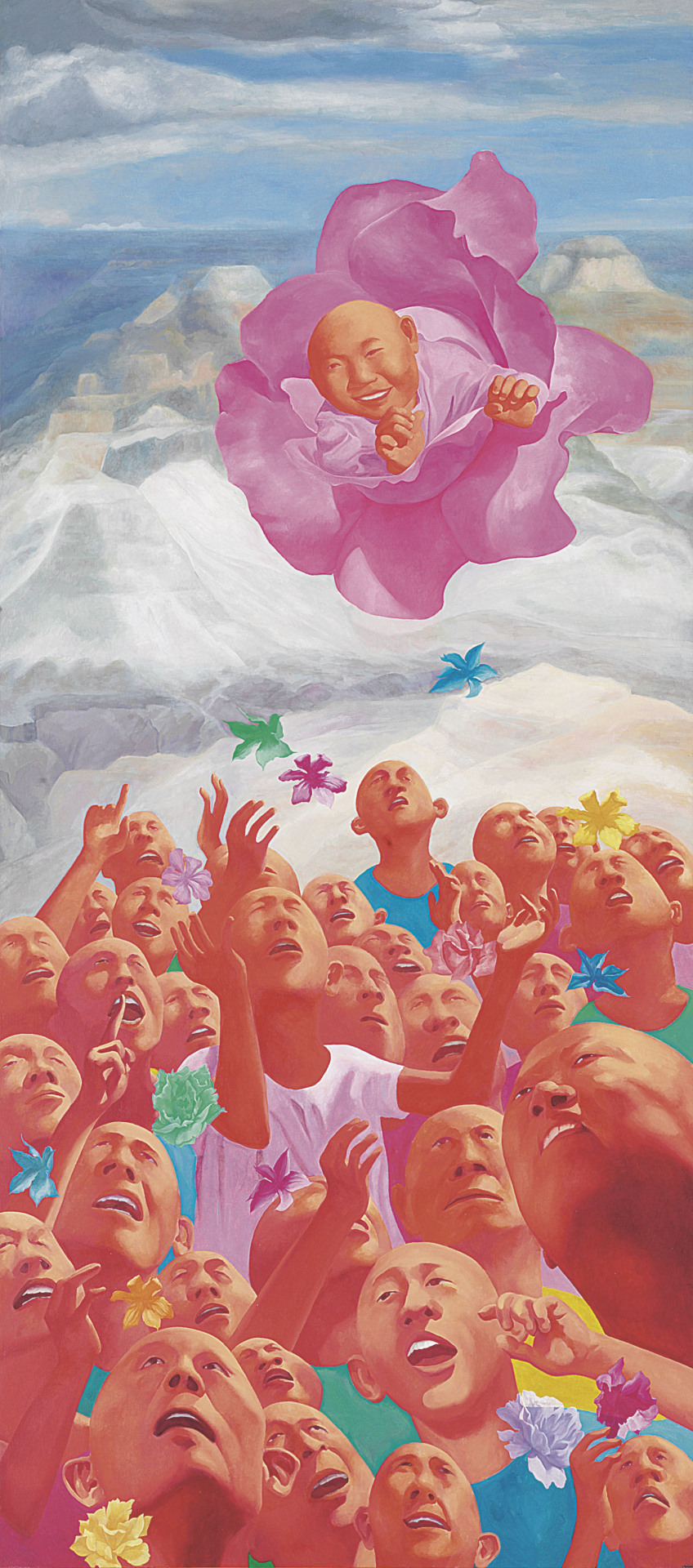

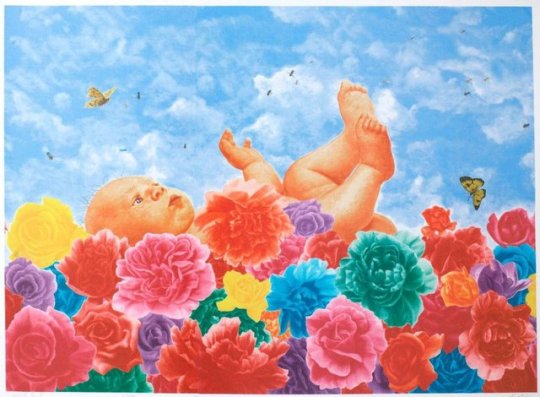

Photo

Fang Lijun (Chinese, b. 1963), 2002. 6. 1, 2002. Oil on canvas, 270 x 120 cm

168 notes

·

View notes

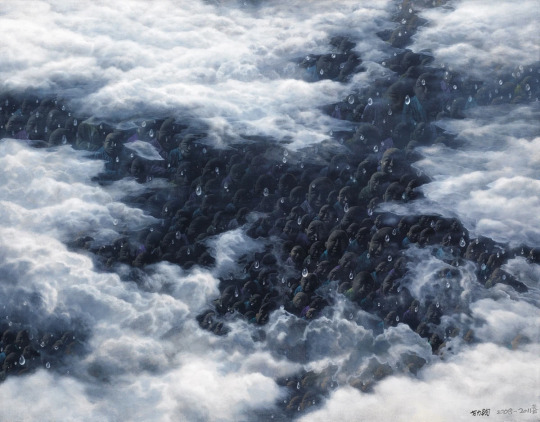

Text

Fang Lijun (b. 1963) - 2006.11.1. 2008-2011. Oil on canvas.

46 notes

·

View notes

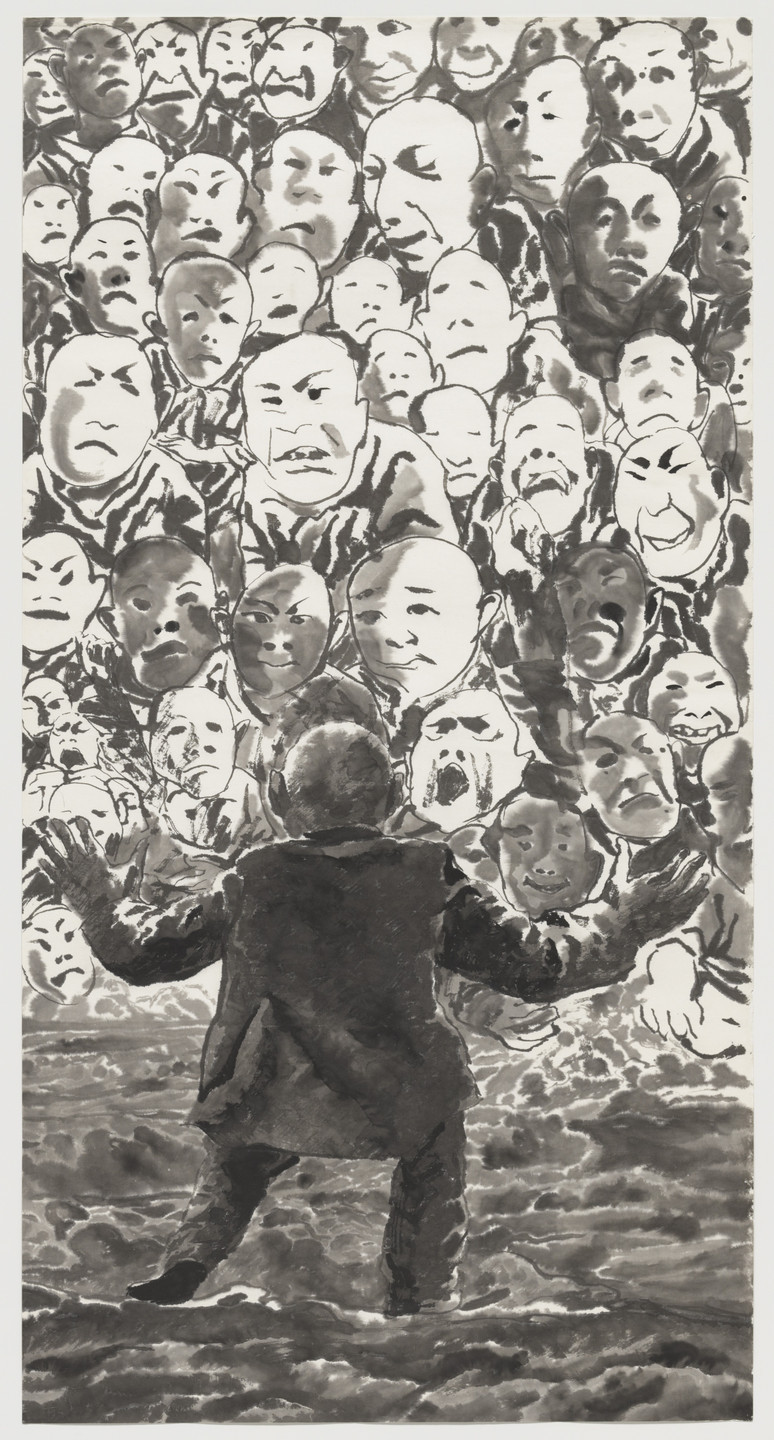

Photo

“O silêncio (a multidão chinesa é vulgarmente uma das mais barulhentas) anunciava um fim do mundo.”

André Malraux, “A Condição Humana”; pintura de Fang Lijun.

15 notes

·

View notes

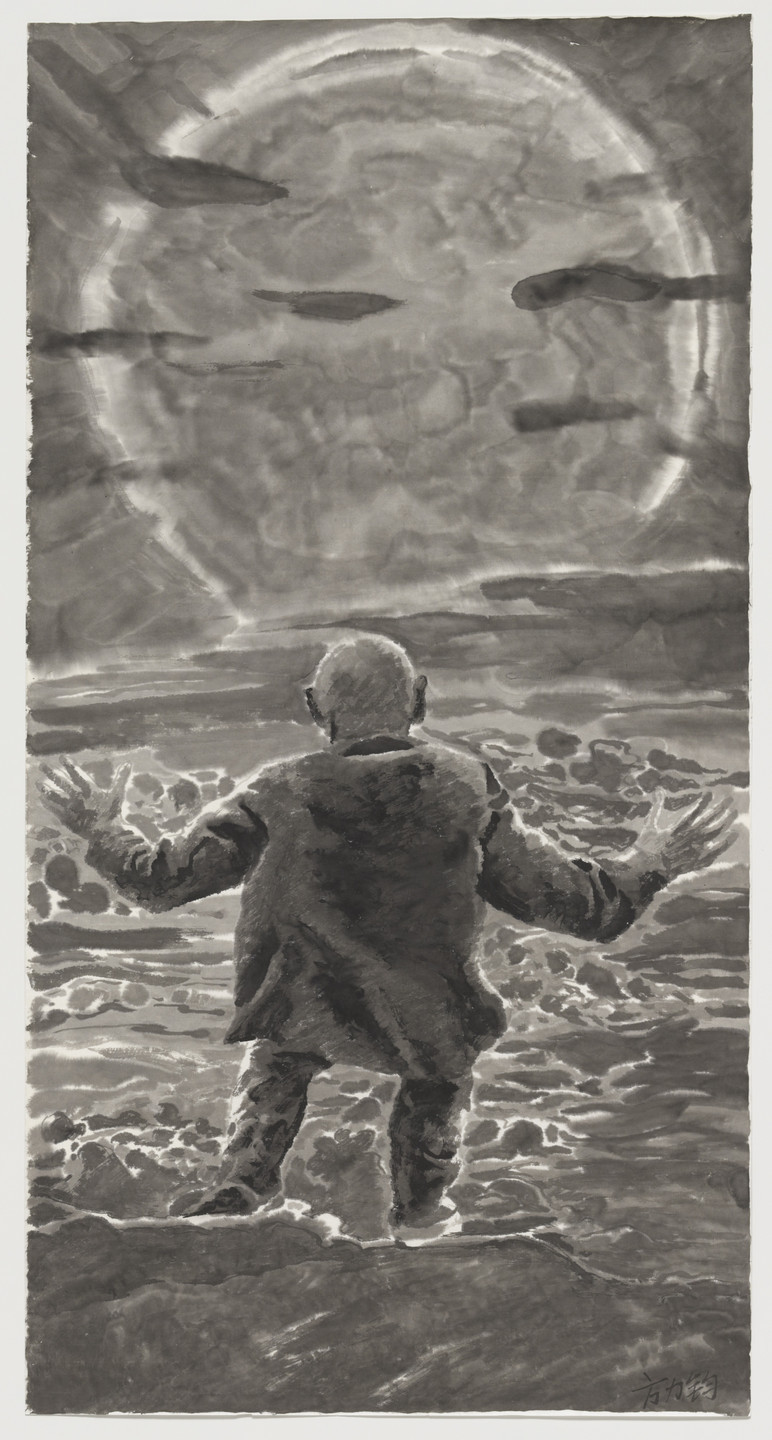

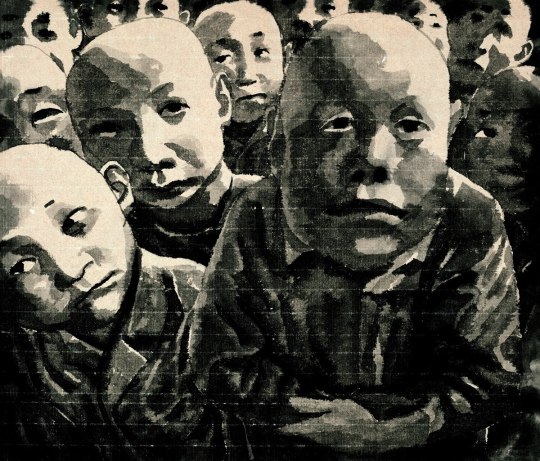

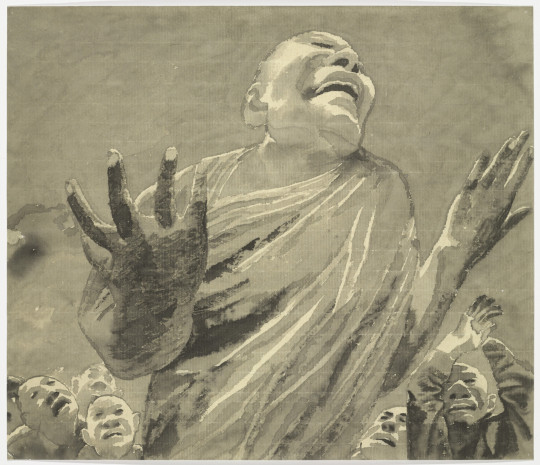

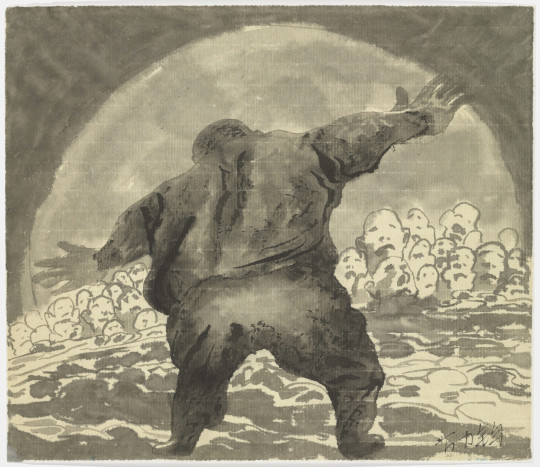

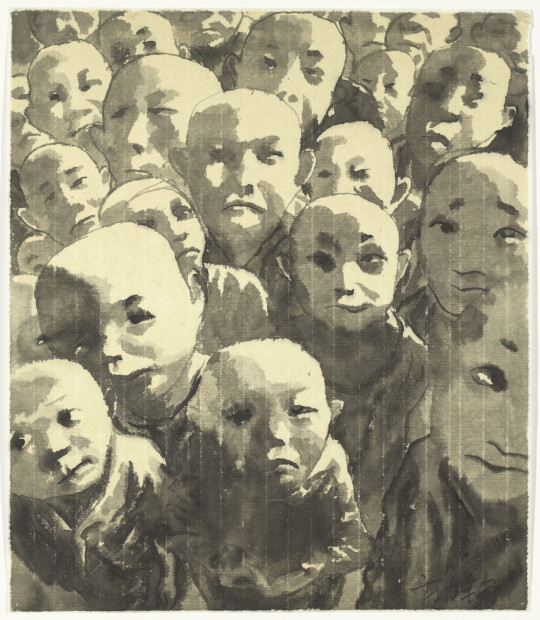

Photo

Fang Lijun

Ink-and-Wash Painting (No. 2, 3, 15, 16, 25, & 11)

(2004)

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fang Lijun https://www.ecfa.com/fang-lijun

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Check out Fang Lijun 方力钧, portrait (2009), From Soemo Fine Arts

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOT Collection: Membrane of the Time / Special feature | YOKOO Tadanori―Ever ...

... HAN Ishu, Thomas DEMAND, FANG Lijun in an attempt to look at the changing concepts of the body and outlook on life that is observed there.

0 notes

Photo

Fang Lijun (Chinese, 1963), Series 2, No. 9, 1991-92. Oil on canvas, 75 x 100 cm.

119 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fang Lijun (Chinese, b. 1963), 2001.7.25. Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 79 cm

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

2006, A new method of playing with illusion and reality, Chungwoo Lee

A new method of playing with illusion and reality – Gwon O-Sang

“A new technique of illusions making tiny but visible cracks in the territory of the Korean art scene established by the 1990s”

Chungwoo Lee, Art in Culture, Editor-in-Chief, http://crazyseoul.com

Leaving behind all that is “so 1990s”

On February 17, 2004, at the opening of the Real Reality show at Kukje Gallery, the artist Gwon O-Sang seemed to have put everything that was of the 90s behind him, and in doing so, marked a small but significant victory. Through Real Reality, Gwon became the first artist to come knocking on the doors of commercial success, and move beyond the obscure fray of the present art scene, largely made up of “second-generation baby boomer” artists and established by the tendencies of the 1990s. (“Second-generation baby boomers” refers to those born in Korea in the early-and mid-1970s. The birth rate statistics chart for post-war Korea resembles a camel with two humps. The first generation of baby boomers was born in the mid-and late-1960s, and the talkative and problematic 386 generation constitutes its core group.[1] While the population momentarily paused in 1971, the figures exploded again in the mid-1970s. Those born during that time are the second-generation baby boomers, known as the “Seo Taiji” [2]generation, which led the way to a mass consumer culture.) Real Reality represented a very significant event, as the first show within the domestic commercial gallery system that featured young Korean artists in their early 30s as the exhibition headliners. (In form, Real Reality was a four-person show that included Bae Bien-U (b.1950), Gwon O-Sang (b.1974), Lee Yoon-jean (b.1972) and Lee Joong-keun; in actuality, it was more like a three-person show of Gwon, Lee Yoon-jean and Lee Joong-keun.) When editions of the works in the show sold in large numbers following the opening, this served as proof that a domestic market able to handle young Korean artists really did exist. Did this mean that a new “niche market” had been cultivated? Sure enough, a little later on in February 2005, Gwon captured the public eye when he was chosen by Ci Kim (Kim Chang-il), head of Arario Gallery, to be a represented by Arario, and the artist soon entered a one-year hiatus. (As of 2006, Arario Gallery represents a total of 8 Korean artists: Gwon O-Sang, Koo Dong-hee, Lee Hyungkoo, Chung Sue-jin, Baek Hyun-jin, Park Sejin, Lee Dong-wook, and Jeon Joon-ho; and seven major Chinese artists: Wang Guanyi, Yue Minjun, Zhang Xiaogang, Liu Jianhua, Sui Jianguo, Fang Lijun, and Zeng Hao.)

The Korean art scene’s current situation is a rather strange affair. Actually, for the past couple of years, the same tiresome state of affairs continued. However, maybe because a “conversion to good quality” was naturally bound to come around, a period of change that diverged from the “1990s system” finally arrived. For the past couple of years, the art scene was based in a value system forged during the 1990s, with a number of exhibitions and events playing a pivotal role in its formation: the 1993 Whitney Biennale in Seoul; the 1998 Seoul in Media—Food, Clothing, Shelter show; ArtSonje exhibitions, the Ssamzie Residency Program, and the formation of alternative spaces like Pool, Sarubia and Loop. However, the emergence of a “young artist boom” following the 1998 Seoul in Media show did not directly translate into commercial success and resembled more of a bubble effect, with the only fruits of success harvested, without exception, by the generation of artists led by Lee Bul and Choi Jeong-hwa. However, Lee already looks on the verge of being over-consumed and exhausted, while Choi, who for a while seemed to have fallen behind in the competition, gave up the possibility of making the 1990s truly his own. (Choi Jeong-hwa’s first museum solo show had been planned for October 2004 at Rodin Gallery but was cancelled. “Victory” very nearly could have been his.) Yet these already obvious shifts could have just been due to the change in major exhibition spaces. The decline of 1990s values started to become visible following the close of Ho-Am Gallery in February 2004, and was even more acutely felt after Director Kim Sun-jung’s ArtSonje closed its doors in December 2004. And of course, that is not all.

The alternative spaces so vocal in the past about their founding objectives, seem to have become, somewhat differently from their inception, the gateway for “study-abroad students” coming back to have “homecoming” exhibitions, (or maybe that was what they were supposed to be from the beginning?), and they, along with their selected artists, appear to be in the process of aging prematurely. Out of the blue, Alternative Space Loop built a building and turned into an awkward commercial gallery in late 2005, and Alternative Space Pool closed its Insa-dong period and moved to Gugi-dong in 2005, while Insa Art Space, which claimed that “it had never been an alternative space in the first place,” moved to Gwanhun-dong in 2006, saying that it would now “focus on archiving and developing research” (namely, it would no longer concentrate on exhibitions). The Ssamzie art industry, which split up and expanded into Ssamzie Space, Ssamzie Residency, Ssamzie Art Warehouse, Ssamzie Gallery, Ssem-Ssem Clubhouse, etc., seems unable grasp what real planning entails, with Director Kim Hong-hee focusing her attention on organizing the 2006 Gwangju Biennale (Although the artists in the 2005 residency program are much better than those in the previous one). In the case of Art Center Nabi, headed by Director Noh So-young, it is rather negligible in terms of the influence it has on the art world (unlike Ssamzie or ArtSonje), even though quite a lot of money was spent over the years. Of course, while the opening of the new Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in October 2004 brought some fresh air to a Korean art world clouded by the signs of premature aging, it was nothing more than the axis of a new power that brought about the demise of 1990s values. Then, is it possible for the Arario Gallery artists, with Gwon O-Sang at the head, to open up a new territory? This period in February 2006, just before Gwon’s second solo show, is a strangely dimwitted and forward-looking moment.

For a while, Gwon was called the Korean artist who “had talent, but no luck,” having applied to the Ssamzie Residency program three times and getting dropped each time. But after showing at Kukje Gallery and signing on with Arario Gallery, hardly anyone considers him an artist short on luck. So before we see the new works in his upcoming show in March 2006, let’s take a careful look at what he has produced in the past.

The beginnings of his work: Making light sculptures

Gwon’s photo-sculptures, which look as if David Hockney’s panorama photo works had been turned into solid, three-dimensional bodies, give such a strong impression that they are hard to forget after seeing them just once. His first works, “A Demand of Proof” and a series called A Tenacious Report on Power, all made in 1998, had the slightly unfinished feel of amateur work, but were equally as strong. The works from 1998 were large enough to fit on top of a studio work table, and were completely hollow inside. A sculptural mass was constructed by means of a panoramic montage, or to put it differently, a solid object was made by piecing together photographs. The work process used in these first pieces could be considered quite important. After different parts of the model’s body were shot with the same light source, the film was developed and the prints pieced together to form a sculptural body (made without looking at the model). The fact that Gwon used this process to achieve a sculptural end-result is without precedent in the history of contemporary art. In fact, from the get-go, Gwon’s works have contained an infinite amount of possibilities, since they were born between the two families of the photographic arts, which have increasingly declined to the level of a techno-baroque craft, and the sculptural arts, which have already declined so much that it is hard to make out a direct line of descendants.

The artist, who graduated from the Hong-ikUniversity sculpture department, said that “The gist of earlier works was to make ‘light sculptures.’” So while his photo-sculptures look as if they are solely photographic in nature, they are undoubtedly the offspring of the sculpture family. (On artist Kang Young-mean’s homepage, there is a link to Gwon’s own site, and he is surprisingly introduced as a sculptor. In the Korean art world, Gwon has been widely recognized as someone working in photography; not once has he been called a sculptor. So, Kang’s usage of “sculptor” to introduce Gwon struck me as very strange.) However, it seems that the artist did not precisely calculate the relationship between the surface appearance created by the photographs and the sculptural mass. Because the first works that he made in 1998 were paper sculptures made solely with photographic prints, they were incredibly weak; so when he increased the size shortly thereafter, he made an “interior structure” to support the paper-sculptures. Once he created these interior structures, his early rationale of using a sequence of photo prints to construct solid bodies immediately converted into an aesthetic of Potemkin facades (This term refers to fictitious, optical-illusion architecture and derives from the false buildings and facades that Gregory Potemkin made for Catherine the Great in the late 18th century.) Thus, afterwards, it appeared that Gwon was able to create, in a fairly fascinating manner, variations on a world of false sculptures that resembled the props and sets of television shows. (The relaxed rules of his work conditions appear to have secured for the artist a certain amount of semi-autonomy.)

The development of photo-sculptures as photogenic as TV show sets

Gwon’s first major work, “A Family Photo of 440 Pieces Composed of Tenacity,” was completed in 1999. This piece featured the artist’s parents seated on chairs and appears to have been the first piece where a metal armature was produced. But because of structural problems, the artist has kept the partially damaged work in his studio. Looking at documentary photos of the piece, it was originally displayed along with a photo of the four members of the artist’s family, and judging from the documentation, it looks as if the artist might have initially planned on making photo-sculptures of all four members. However, the piece that really fit the bill for his initial goal to create “light sculptures” came with “Unbearable Heaviness,” made in the same year. This sculpture of a rock made from photos taken of a real one easily captured a sense of irony, while the inside of the sculpture was filled with urethane foam. But it doesn’t look like the artist went to the trouble of turning the rock upside down and shooting the bottom. So in a sense, this work too was a fool-the-eye Potemkin façade. It only makes sense that strict modernist heroes would feel hostile toward Gwon.

On the other hand, “A Crumpled Plan on a Dreamy Journey” (1999), a three-dimensional work made by crumpling up C-prints, was unable to establish a sense of irony because of its rather vague line of thought, and thus slides off the side of the network of meaning. The artist called this “the work that couldn’t capture people’s attention,” and this piece, which was part of a series, tended to try a little too hard to look like a “work of art.” The fact that the piece was firmly “installed” above the bathtub in a public bathhouse was rather contrived, but also in the case of the Spoiled Journey series, it’s hard to understand why these photo-sculptures made from crumpled photographs had to be nailed into warped wooden frames. Is it that the warped frames were metaphors symbolizing a “spoiled reality?” (By all means, I would hope not. The only term that has a lamer status than “metaphor” in the contemporary art world would probably be “expression.”) (But the crumpled sculptures do still seem as if they have lots of potential. In contrast to his earlier works, “Pyeongchang-dong” (2002), a piece where a view of Pyeongchang-dong has been crumpled up and put into a section of a window frame, is very successful. As a rare piece by Gwon that is site-specific, issues of landscape and its photographic shooting, the notion of the frame, and the result of a three-dimensional body being made from a crumpled print can all be read in one, clearly explained effort. Of course, in terms of the work process, there is some disappointment over the fact that he couldn’t take the shot without including the window.)

Gwon’s probably best-known work, “A Statement of 280 Pieces on the Absolute Authority and Worship in Art,” was made in 1999, and consisted of a Jesus-like figure nailed to a cross. Thanks to the way this extremely photogenic piece used an illustrative composition that combined religious imagery with Marshall Arisman-like images, it gained much attention. (It’s possible that this was Gwon’s piece de resistance.) But then the brain has a way of tiring immediately of the sugar-coated narrative. A naked man with a dog’s head strung up like Jesus and “ART” written across the top as the name of the crime—-this is, like the title of the piece, a bit long-winded. Thus, even though it has only been five years since its completion, the piece already looks hackneyed, and it seems like the artist considers it a little embarrassing as well.

Seeking diverse work logics

On the other hand, “A Statement of 540 Pieces on Twins” and “A Statement of 420 Pieces on Twins,” two works created in 1999, appear stable even when seen today. Actually, it is no wonder, for this is because these works basically add on classic twists of irony to his original, earlier works.

However, in contrast to the stability of the external appearance, something is a little shaky about the rationale used to construct the works, for, the two circuits making up these twins– their being photo-sculptures, and their Jacques Carelman, “Impossible Object”-like sense of irony—do not quite fit together and form a rather disconnected, short-circuited relationship. Of course, if the artist states that the work is an examination on the possible differences that arise when making a pair of identical sculptures from repeating identical prints, then the doubts that I raised about the “sculpture of irony” can be dismissed. (If the artist claims that “A Demand of the Reduction Composed of 300 Pieces,” a piece from 2000 where the head has been reduced, is a study of size reduction in photographs, then it is possible to defend the work’s logic.)

Yet you no longer have room to make excuses for the disjointed quality of his works with “A Statement of 360 Pieces on the Field of Multiple Vision” (2000), where three ducks’ heads have been attached to a human body. Accordingly, I prefer strictly figurative works like “On the Languishment of 340 Pieces” (2000), where there are no disparate elements that have been juxtaposed, no changes in the human scale, and the basis of the piece is simply the reproduction of photographs through a three-dimensional sculpture. Works like “A Castrated Entry” (2000) and “’Re-assembled Flower Petals” (2000), which could be read as up-scaled sculptural works made with enlarged prints, can also be considered good works. However, I’m a bit displeased by the rather incoherent titles. The majority of his works seem to have been named after their completion, and these rather heavy-handed titles are hard to take in. (Of course, in the case of the sculptures where the number of prints used in their construction has been established, the amount of prints had to be pre-recorded; in which case, the numbers in the titles have been decided beforehand.) Although the artist said that “Because I didn’t consider the titles to be that important to the work, I initially tried to give them an ‘untitled’ feel,’” but it is hard to get this “untitled” feeling, especially when he names a work of a flower with petals and no stamen “A Castrated Entry.” This is why I prefer rather blunt works that have plain names like “A Traveler’s Suitcase” (2000). (It would have been better if works like “Meaningless Emission,” (2000) a reproduction of a heavy-duty garbage bag filled with trash, was just called “Trash.”) If it’s an “untitled feel” he was after, “A Statement of Meaningless 360 Pieces” (2000), which was part of his installation, “A Comfortable Journey,” would have been about it.

Deodorant Type

Gwon says that beginning with his first solo show in 2001 at Insa Art Space, he started to gain recognition as an artist. At his first solo show, where the allegory of a “Deodorant type” was used in the show’s title, a new thread of logic unseen in previous works could be detected. Deodorant type, which could seemingly suggest some new type of photo printing, was borrowed from Nivea brand deodorant. There’s no reason why a deodorant used to cover up armpit smells would sell very well in Korea, but it was at least successful in awakening the interest of an artist named Gwon O-Sang. Then exactly what kind of social narrative does the deodorant allegory elicit? Does this mean that Gwon’s works demonstrate a cover-up and surface-illusion quality, just as the term “deodorant type” suggests the effect of a superficial cover-up? Then does this mean that this exhibition is about concealed set-like constructions and the illusionism of photographs?

The work that first gained attention was “An Alien—A Statement on the Viewfinder Composed of 350 Pieces” (2001), which was used for the show’s advertisement poster. Religious imagery was again used here. The piece was installed so that its feet were lifted slightly off the ground and features an alien-like naked figure in the Amita pose, which symbolizes the present, transient life. I was at a loss to discover what kind of relationship this piece had to the other works. This is because at about the time of this exhibition, Gwon began to borrow from aesthetic elements found commercial advertisements. A quick glance through Gwon’s work notebook revealed that he had made scraps of several images taken from advertisements and fashion magazines. What was really eye-catching was how he had borrowed model’s poses for his sculptures. The position of the Siamese twins featured fighting with their own images in “A Statement of Entangled 480 Pieces” was taken from the poses struck by models in a Gucci ad, while the woman sitting on the ground with one leg extended out in front of her in “A Statement of Meaningless 360 Pieces” (2000) cites an Ungaro ad campaign. Then where did “ChineseGarden,” a piece that reproduces an oddly shaped ornamental rock, such as those particularly loved by the Chinese, find its source? The artist’s response is extremely fascinating:

I have a lot of interest in advertisements. At around the time I was making this piece, the “zen” look was in. Westerners first took in Chinese, Japanese and other Asian cultures as Orientalism, and that Orientalism became revived as a retro trend in the 90s, and I found it fascinating that the style was in turn imported into a country like Korea, where it was circulated and distributed as a very odd form of fashion.

It was at this point that I was able to figure out the hidden thread of the exhibition, and I became slightly restless, as if I had discovered a fascinating secret.

If you look closely, it appears that the photo-sculptures created after his solo exhibition all contain certain elements found in advertisements. This is the case in “Tender” (2002), a piece where a man in a yoga pose has soap suds covering his hands. In the artist’s work files, ad images have been neatly gathered and among them, Dior’s bubble-and-soap suds ad campaign and the Korean fashion shoots that borrowed from the Dior ads catch the eye. Goodness, the artist was much more thorough and precise than I had previously imagined. I made similar discoveries with the three photo-sculptures that he showed at Kukje Gallery. The works featuring his friends from university all take on rather tense poses, and little wonder—the man standing in the hooded tee in “Action Sampler” is the artist-cum-singer and occasional poet Baek Hyun-jin, who gained a name as the singer in the Uhuhboo Project; the man with his head in the bushes, or in “Hyde Park” (2003), is the artist Lee Hyungkoo, who makes strange optical devices; the woman in “Miss” (2003) who is bent over backwards and showing off her shoes is the artist Koo Donghee, known for making witty videos. Looking through the artist’s files, it appears that in the case of “Miss,” the pose from a doll in a Diesel ad was borrowed. (Even more striking are the other ads that feature the same backwards-bend pose.) In the case of the two other works, it is difficult to pinpoint their specific origins, but it is certain that they too have an element of appropriation.

For young artists, the first solo show is an important rite of passage. Most artists become discouraged by the fact that people do not immediately show an enthusiastic response, and they may even feel frustration toward a harsh reality (there are surprisingly few artists who realize that it is not true that a show has to be good in order for magazines and newspapers to write a review), but in fact, good exhibitions have a way of creating unexpected footholds. Gwon’s solo exhibition caught the eye of ArtSonje Director Kim Sun-jung, and Kim purchased the oddly-positioned twins caught up a bad relationship, or “A Statement of Entangled 480 Pieces.” For Gwon, this was his first sale. The artist said that he gained confidence afterwards. And this was probably not only a confidence booster in terms of his work, but a boost because a piece lacking structural stability had been sold. And just in the knick of time—the artist had just before contemplated selling the prints used to make the sculptures by framing and editioning them, just to sell some work. (The artist said that he had arranged the prints used in photo-sculptures in a flat format in an actual exhibition.) However, after this first purchase, those kinds of works were not realized. This is how a sharp-eyed collector’s small decision became a large boon, and not just in terms of money, to the artist. ( “Fear of 280 Pieces” from 2001, which was featured in his solo show, was sold in Japan when it was exhibited there. This was the first overseas sale for the artist.)

The easy overcoming of a sophomore complex

Young artists are often troubled by a sophomore complex (particularly the more so if they succeed with sparkling ideas). However, Gwon was easily able to push this period aside. Beginning in 2002, Gwon gained much popularity as an artist and was asked to participate in both small and large exhibitions abroad. Once they are consumed by the system, many artists cannot get a hold over themselves and, being unable to produce new works, waste energy trying to match the schedules of any exhibition within sight. Gwon was no different. Over some drinks, the artist quietly mumbled the peculiar words, “I didn’t even have the chance to get depressed over the fact that I had turned 30 because I’ve been so busy.” But in contrast to the other artists his age, he was able to gain some time by creating a new series called The Flat (2003) (and in the process gained a little money too). The Flat series is the safety work that has secured the artist some time for thought, so that he can make further progress. On top of that, this work continues on the theme of the strange contrast found in his photo-sculpture works, and as another “big idea,” makes his previous works look even more striking.

The Flat series is the culmination of an eye-fooling Potemkin façade. In this work where photographs of watches have been cut out from magazines and laid out according to different types and then re-photographed, he stimulates people’s worldly desires. But the objects so teeming with life in the works are all fake. Some of the ads stand on paper legs, but others, propped up on wires, can barely hold their ground. If you look closely at the print, little bits of wire are visible. This mischievous piece has so many possibilities and directions that it can go in, it’s fun just thinking about what future spin-offs might look like. (The artist said that for later works, he is thinking about shooting all of the objects featured in the March issue of GQ magazine, or perfumes, cameras, etc. The idea of shooting the magazine issue is undoubtedly a fabulous idea. That’s definitely a sharp one.) When I first saw this work, I thought that Gwon was simply exploiting countless photographers. Probably the most difficult and laborious thing to shoot are those objects deemed “luxury goods.” Each object is shot using the best conditions and photographers. (Especially in the case of products that have a reflection like watches, the shooting must be even more rigorous so that the photographer or camera is not shown in the watch. It is no easy task.) Each of the aesthetic heights of perfection attained within this elaborate system is quite simply appropriated in The Flat. This is an “art of plundering” that cannot be blamed. It’s fantastic. But the episode that started it all is even more so.

One day, the artist Lee Hyungkoo was visiting Gwon’s studio and out of the blue, he said that if you go to Namdaemun Market, you can get “bling-bling watches” that look real, and that it would be a riot if Gwon bought one and was seen wearing it at an art opening. So on the spot, Gwon cut out a “bling-bling watch” and fastened it around Lee’s wrist. It was as good as gold. Afterwards, the paper watch was placed on the wrist of the “twins” piece found at the entrance to Gwon’s studio, and the artist remarked that no one had a clue that it was just a flimsy piece of paper. Once this began, Gwon, who had initially made up his mind to make still life photo works, began to work on “still life works” made from magazine cut-outs. Props to Lee Hyungkoo.

Spielraum[3]–The space that will unfold next

Just because Gwon is spending his time on “still life photos” does not mean that the questions and themes posed by his earlier works have been resolved. Gwon needs to come up with a more elaborate, historically-bound reasoning to deal with the issue of flat photographs becoming three-dimensional forms. Of the remarks made on his works by critics, the one that bothered him the most was that “well, if you look at the work as sculptures, they don’t amount to much.” The precise quote is the following. “…If you read his works as sculptures, no real issue is posed by them. This is because they are no more than sculptures made by using an easy formula where the obligation to depict something is just put onto the photograph….” (Kim Seung-hyun, Jirokwima,[4] exhibition preface, 2000). This is the vital point that indicates with certainty that the artist thinks of his work as “sculpture.” However, in order for the artist’s photo-sculptures to be recognized as a legitimate child of the rather old-fashioned family of contemporary sculpture, there are a number of processes that must be elaborated upon. If the historical phase that his works carry as sculptures becomes clearer, then through that, the history of sculpture itself will have to take into account those things that exist beyond a traditional history of the sculptural arts—like the previously-excluded Potemkin façade entities that resemble TV-set props; this process would entail going through a grueling trial. But if the rationale behind the artist’s works do not become clearer, then his photo-sculptures, different from the conceptualized, “objectual” sculptures of artist Chung Seo-young, may not succeed in gaining the status of “legitimate children of the sculpture family.” Unfortunately, the responsibility of establishing proof lies with the artist.

And that’s not all. In order to properly conserve and sell his works, he has to solve the difficult problem of structural durability. (For quite some time, in the case that a photo-sculpture is sold, he has promised to repair defects. But after becoming a so-called “successful artist,” it would be a rather embarrassing thing to go about doing repair work.) And there’s still more. The selected facets borrowed from advertisements are still vague. Only afterwards when more works have accumulated, will it be possible to read and evaluate a meta-narrative of those hidden threads, but if those works start to be read according to the artist’s arbitrary choices, then they could become nothing more than forms of “self-expression.” Of course, it’s still too early to worry. He is but a young artist of 33, still at an age where he has just reached the door of success. The spaces that will open up before him appear as if they will grant him quite a lot of semi-autonomy. Already, in his right hand he holds the rights to a diamond mine (photo-sculptures), and in his left hand he possesses the rights to a gold mine (flat works). If he chooses to dig the diamond mine, he will have to continue struggling, but for now, he will gain some time by exploring the gold mine. (As the critic Hal Foster said) This can only be successful if the artist’s semi-autonomy is used as a tactical method. If the artist unduly grants himself an unprincipled semi-autonomy, then the unlimited freedom and time that unfolds may become a fatal poison. Gwon O-sang now stands at the crossroads.

* This essay was originally prepared in April 2004 as a part of the “Korean Contemporary Artist Studies Project and was revised in February 2006.

0 notes