#eduard riou

Text

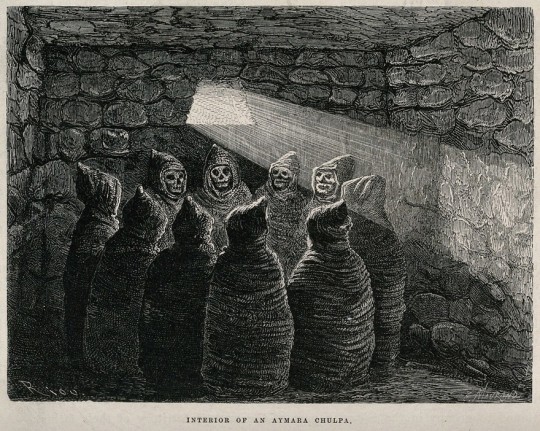

'Ten Corpses inside a chulpa (mausoleum) among the Aymara tribe'.

Woodengraving by 'Ten Corpses inside a chulpa (mausoleum) among the Aymara tribe'. Woodengraving by Charles Maurand after Eduard Riou, 1873 after Eduard Riou, 1873.

579 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Éduard Riou, Condensation et chute des eaux sur le globe primitif, in La terre avant le déluge , 1863

L'auteur de cette estampe est le français Édouard Riou (1833-1900), peintre paysagiste et illustrateur d'un texte scientifique de Guillaume Louis Figuier (1819-1894), La Terre avant le déluge , publié par Hachette à Paris en 1863. Son sont les images du temps profond qui enrichissent le volume et qui, comme nous le verrons bientôt, susciteront l'intérêt au-delà de la sphère scientifique.

Condensation et chute des eaux sur le globe primitif est la première illustration de Riou. Figuier décrit ainsi les premières eaux qui tombent à la surface de la Terre qui progressivement se refroidit et s'évapore du fait de l'élévation de sa température :

« Plus légères que le reste de l'atmosphère, ces vapeurs s'élevaient vers les extrémités supérieures de la zone atmosphérique et s'y refroidissaient et rayonnaient vers les régions glaciaires de l'espace. Ils se condensaient à nouveau, retombaient au sol encore à l'état liquide, pour remonter sous forme de vapeur et précipitaient toujours à l'état de condensation. Mais ces changements dans l'état physique de l'eau ne pouvaient être entretenus que par une quantité considérable de chaleur à la surface du globe, et l'oscillation incessante du chaud et du froid accélérait le refroidissement : la chaleur se perdait ainsi peu à peu jusqu'à s'évanouir dans l'eau. régions de l'espace céleste. […] Des détonations de tonnerre et d'intenses éclairs de lumière ont ainsi accompagné cette extraordinaire lutte des éléments » [2] .

Un passage qui permet d'éclairer le contexte dans lequel Riou se trouve opérer : ses illustrations doivent se conformer à une dramaturgie précise, à une écriture qui répond à la prose scientifique et qui a pour protagoniste la Terre, ou plutôt ce globe incandescent et ce primitif mer décrit ci-dessus.

(via Max Ernst, l'intemporel - Riccardo Venturi)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

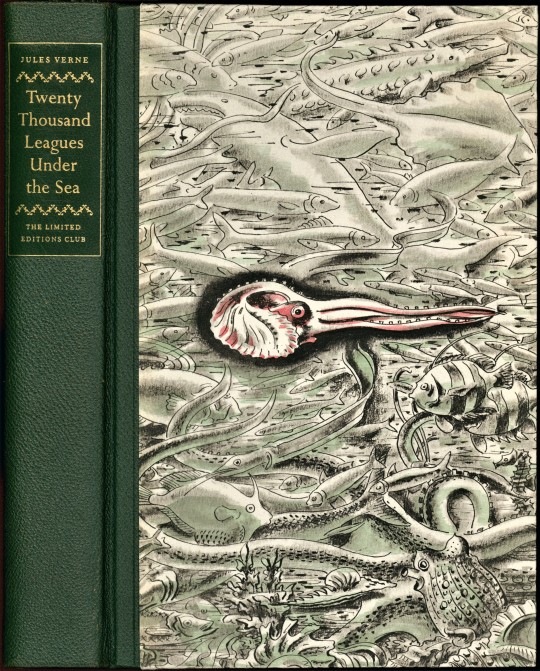

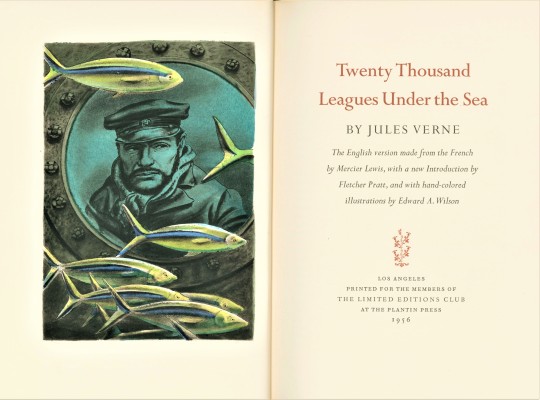

It’s Fine Press Friday!

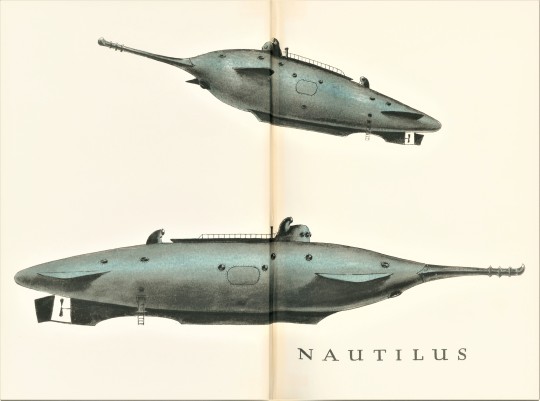

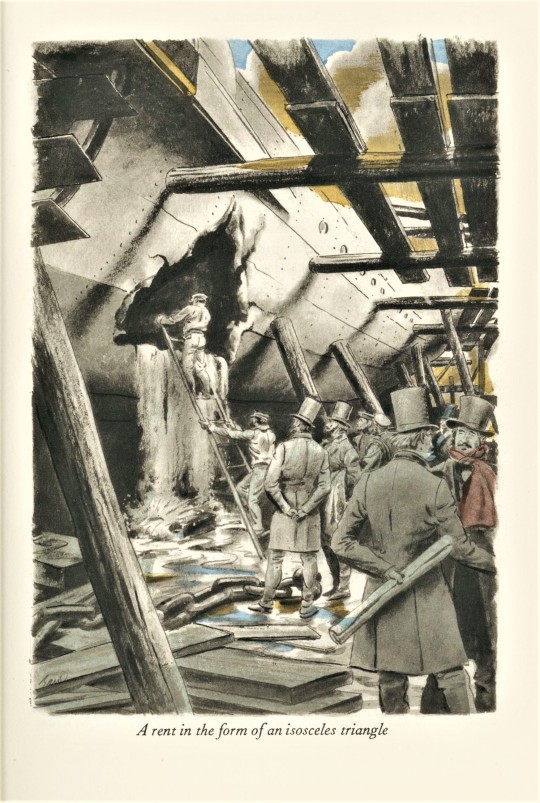

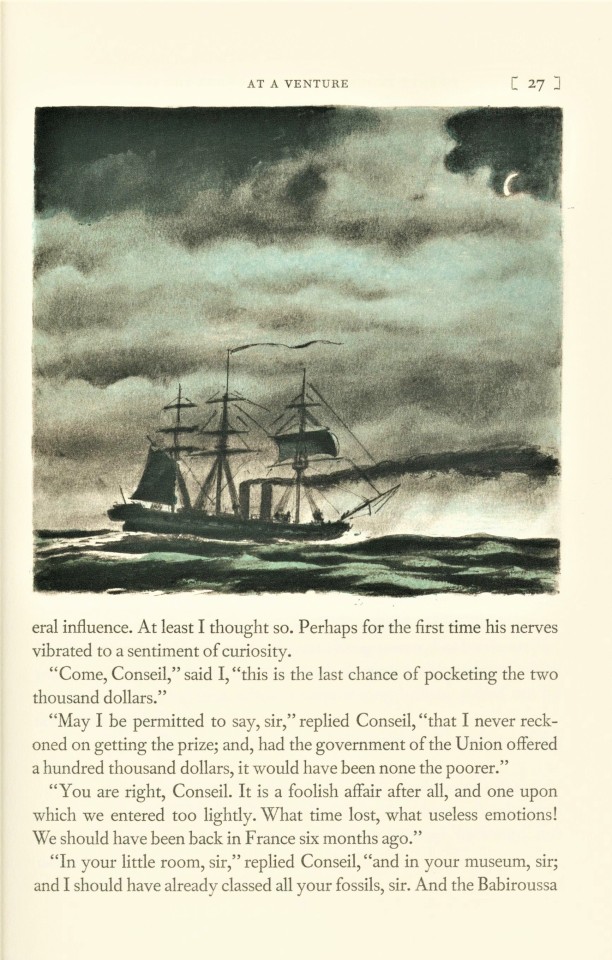

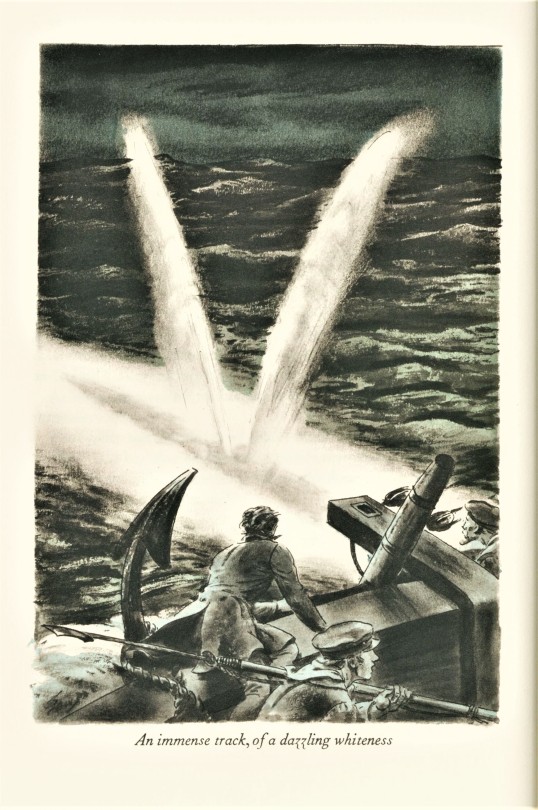

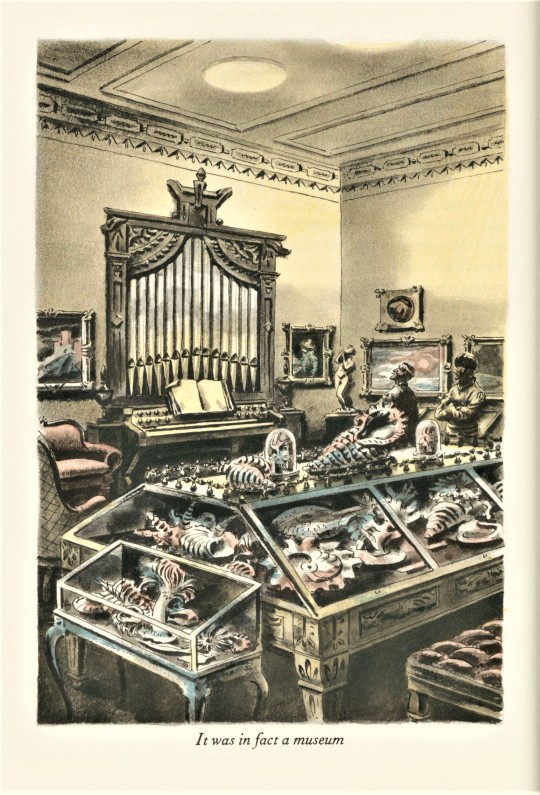

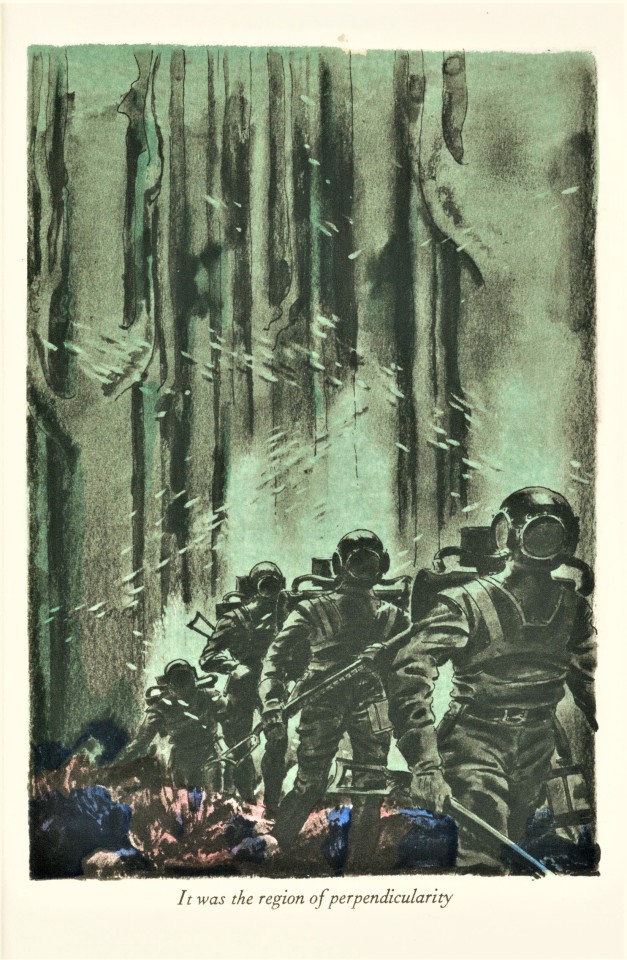

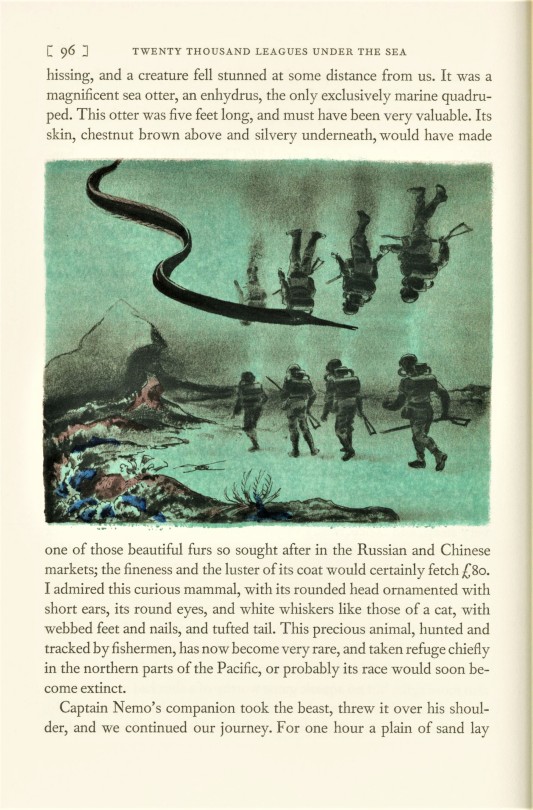

This week we bring you Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne, illustrated by Edward A. Wilson, and printed in 1956 for the members of The Limited Editions Club at The Plantin Press in an edition of fifteen-hundred copies signed by the illustrator.

This classic of science fiction adventure novels was first published in a serial format, from March 1869 to June 1870, as part of a Verne’s series called Voyages Extraordinaries, in Magasin d'éducation et de récréation, a magazine founded by the French editor and publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel. There would be a total of fifty-four novels in this series published during the author’s lifetime, between 1863 and 1905.

This novel is considered to be one of Verne’s greatest works, along with Around the World in Eighty Days and Journey to the Center of the Earth, which are a part of the same series. The books were meant to depict historical and scientific knowledge. In particular, Verne’s descriptions of submarines would turn out to be surprisingly accurate considering the primitive technology that existed at the time he wrote the book.

Once a novel completed its serial release in the magazine, it would be published in book form, typically in three editions, one without illustrations, a second with a few illustrations, and one richly illustrated version in a deluxe octavo format.

The first deluxe edition of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea was published in November, 1871. Just in time for Christmas shoppers. The French academic painter Alphonse de Neuville and Eduard Riou together produced 111 illustrations for the book. Eduard Riou illustrated six of Jules Verne’s novels.

The tradition continues here, where this text is accompanied by the work of American illustrator, printmaker and commercial artist, Edward A. Wilson. Wilson’s illustrations were transferred and printed in gravure by the Photogravure and Color Company of New Jersey. The gravure’s were then hand colored in the studio of Martha Berrien in New York. The book is quarter bound in green leather and covered with a paper that has been printed with a decorative illustration and hand-colored. The type was set in Monotype Fournier and printed by Saul and Lillian Marks at their Plantin Press in Los Angeles on a paper made especially for this book by the Curtis Paper Company.

Use this link for more Fine Press Friday posts!

Use this link for more Limited Editions Club posts!

Teddy- Special Collections Graduate Intern.

#Fine Press Friday#Fine Press Fridays#juels verne#Edward A. Wilson#edward wilson#Limited Editions Club#twenty thousand leagues under the sea#Voyages Extraordinaries#science fiction#Pierre-Jules Hetzel#Saul and Lillian Marks#photogravures#Photogravure and Color Company#teddy#Martha Berrien#Curtis Paper Company#fine press books#plantin press

125 notes

·

View notes

Photo

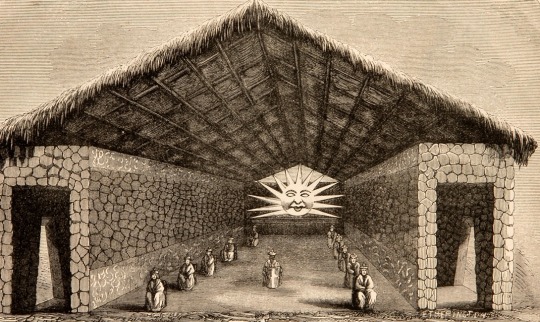

Eduard Riou. Interior of the The Temple of the Sun During the Later Reign of the Incas, from Paul Marcoy, Travels in South America. 1875.

#eduard riou#interior of the temple of the sun#incas#paul marcoy- travels in south america#engraving#the temple of the sun#19th century#illustration#dumbarton oaks#harvard#magictransistor#alejandromerola#1875#mtr#mtradio#South America#Inca#art#history#anthropology

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient plankton hint at climate to come

The Pliocene, a geological epoch between two and five million years ago with CO2 levels similar to today, is a good analog for future climate predictions, according to a new study.

The Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii recently recorded the highest concentration of carbon dioxide levels in human history. The last time CO2 levels surpassed 400 parts per million was during the Pliocene, when oceans surged 50 feet higher and small icecaps barely clung to the poles.

“The Pliocene wasn’t a world that humans and our ancestors were a part of,” says lead author Jessica Tierney, associate professor of geosciences at the University of Arizona. “We just started to evolve at the end of it.”

A wood engraving by Eduard Riou depicts a landscape view of the Pliocene. The image was etched in the late 1800s, when CO2 levels hovered around 295 ppm. (Credit: Welcome Library)

Now that we’ve reached 415 parts per million CO2, Tierney thinks researchers can use the Pliocene to understand the climate shifts of the very near future. Past studies attempted this, but a nagging discrepancy between climate models and fossil data from that part of Earth’s history muddled any potential insights.

The new study in Geophysical Research Letters, which used a different, more reliable type of fossil data than past studies, resolves the discrepancy between fossil data and climate model simulations.

Funky changes

Before the Industrial Revolution, CO2 levels hovered around 280 ppm. For perspective, it took over two million years for CO2 levels to naturally decline from 400 ppm to pre-industrial levels. In just over 150 years, humanity has caused those levels to rebound.

Past proxy measurements of Pliocene sea surface temperatures led scientists to conclude that a warmer Earth caused the tropical Pacific Ocean to be stuck in an equatorial weather pattern called El Niño.

Normally, as the trade winds sweep across the warm surface waters of the Pacific Ocean from east to west, warm water piles up in the eastern Pacific, cooling the western side of the ocean by about 7 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit. But during an El Niño, the temperature difference between the east and west drops to just under 2 degrees, influencing weather patterns around the world, including Southern Arizona. El Niños typically occur about every three to seven years, Tierney says.

The problem is, climate models of the Pliocene, which included CO2 levels of 400 ppm, couldn’t seem to simulate a permanent El Niño without making funky, unrealistic changes to model conditions.

“This paper was designed to revisit that concept of the permanent El Niño and see if it really holds up against a reanalysis of the data,” she says. “We find it doesn’t hold up.”

Fat thermometers for Pliocene temperature

About 20 years ago, scientists found they could deduce past temperatures based on chemical analysis of a specific kind of fossilized shell of a type of plankton called foraminifera.

“We don’t have thermometers that can go to the Pliocene, so we have to use proxy data instead,” Tierney says.

Since then, scientists have learned that ocean chemistry can skew foraminifera measurements, so Tierney and her team instead used a different proxy measurement—the fat produced by another plankton called coccolithophores. When the environment is warm, coccolithophores produce a slightly different kind of fat than when it’s cold, and paleoclimatologists can read the changes in the fat, preserved in ocean sediments, to deduce sea-surface temperatures.

“This is a really commonly used and reliable way to look at past temperatures, so a lot of people have made these measurements in the Pliocene. We have data from all over the world,” Tierney says. “Now we use this fat thermometer that we know doesn’t have complications, and we’re sure we can get a cleaner result.”

‘It all checks out’

The researchers found that the temperature difference between the eastern and western sides of the Pacific did decrease, but not enough to qualify as a full-fledged permanent El Niño.

“We didn’t have a permanent El Niño, so that was a bit of an extreme interpretation of what happened. But there is a reduction in the east-west difference—that’s still true.”

The eastern Pacific got warmer than the western, which caused the trade winds to slacken and changed precipitation patterns. Dry places like Peru and Arizona might have been wetter. These results from the Pliocene agree with what future climate models have predicted, as a result of CO2 levels reaching 400 ppm.

This is promising because now the proxy data matches the Pliocene climate models. “It all checks out,” Tierney says.

The Pliocene, however, was during a time in Earth’s history when the climate was slowly cooling. Today, the climate is getting hotter very quickly. Can we really expect a similar climate?

“The reason today sea levels and ice sheets don’t quite match the climate of the Pliocene is because it takes time for ice sheets to melt,” Tierney says.

“However, the changes in the atmosphere that happen in response to CO2—like the changes in the trade winds and rainfall patterns—can definitely occur within the span of a human life.”

Source: Mikayla Mace for University of Arizona

The post Ancient plankton hint at climate to come appeared first on Futurity.

Ancient plankton hint at climate to come published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes