#does he know how to conjugate verbs in mando'a!!?? no! but i do!

Photo

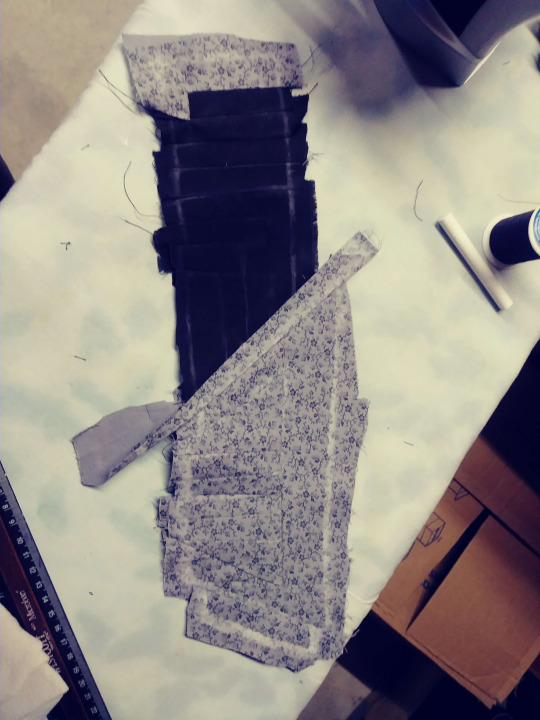

I procrastinated figuring out how to use my fancy new sewing machine SO hard i made a quilt design about it, and then started making the quilt, with the sewing machine, so i think i’m procrastinating so hard it’s coming back around into productivity? this is wayyyy too fucking ambitious for my first quilt and i have no idea what the fuck i’m doing but! that will not stop me!

originally the design was much larger and for a queen size, and then i got out a yardstick and realized that’s way too fucking big so i downsized the scale and moved things around and added more buy’cese, i’m not sold on the background color and i’m prob not going to embroider the crusader’s emblem or the vizsla emblem like i had planned bc it stands out too much, but i was thinking of stitching the mythosaur symbol down the vertical sides, but i could also do lines of “bic cuyir te ara” since i’m already gonna be hand stitching so much goddamn mando’a

i’m pretty sure i can program custom embroidery patterns into my fancy machine (which is the whole thing i’m procrastinating about so finishing all the buy’cese will force me to find out) so i want to do the resol’nare in gold, but i don’t think anything with gold filament is gonna be strong enough for that so i may do yellow and embroider a bit in gold filament just to get around that, and then i’m still sorting through what patterns i wanna do across the quilt, i was thinking random concentric squares of lines of text, that way i could do kote darasuum around where cody is and a much bigger one spreading from the taung at the bottom with a version of dha werda verda (still haven’t figured out which one to use), but then i don’t know what to do about the rest of the quilt, and like do i really want to hand stitch everything in mando’a characters (resigned)

so obviously what i’m using here is a mix of different canons with some fanon sprinkled in (sue me, canon mandalor the uniter fucking sucks, basic bitch buy’ce, so i replaced that one with the irl dude’s mandalorian oc of the same title bc quite frankly it’s more meaningful to the fandom and it looks fucking sick), some of them had very little canon material to work with so i tried my best to wing it (tarre vizsla didn’t really have a buy’ce per se so i’m still debating using matte black for that one), some i picked bc they looked cool and not because they’re relevant, some i left out purposefully

i started with the darksaber, because i thought “it’s smaller and just a bunch of straight lines, how hard can it be?” but it turns out needle-point turn on all those stupid tiny corners is, in fact, a new layer of hell i had previously remained oblivious to, but i still did it, and it’s only a little wonky

ok so the quality is shit, but it’ll look real nice when i fucking needle-point turn applique this shit to the top layer and then detail it all in silver when i’ve got all the sandwich together, and i’m real fucking proud of myself for getting the first bucket done, and it even mostly lays flat!

i’ve got this stupid shiny black fabric i’m using for all the visors and it is definitely painful as hell to work with but god does it look nice

#quilting#mandalorian#mando'a#nobody i know cares about star wars enough for me to ramble about my stupid quilt#the person im making this for isn't even gonna get all the cool little easter eggs i'm utting into this shit#does he know how to conjugate verbs in mando'a!!?? no! but i do!#like the gods all have eyes in their visors#mandalor the lesser being placed by hod ha'ran the trickster god bc he was a sith puppet#oooog but i don't know what i'm going to do with the original mand'alor one#maybe take some gold lines to it after i've attached the base to the quilt?#program some embroidery lines before i sew it to anything?#there is no way in hell i'm cutting up all those tiny ass pieces and then sewing them all together#that wouldn't even be visible at the end and really it needs to be a lot more visually striking for what it is#ooo maybe i could stitch the jedi code translated into mando'a over tarre vizsla and the darksaber#like the fact that it would go under the resol'nare is perfect

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basics of Mando'a Grammar

There doesn’t seem to be a single, comprehensive resource for Mando'a grammar on tumblr (that I’ve found), so I thought I’d compile a basic intro post for people who are eager to learn the language but unsure how or where to start. This is coming from an English-speaking perspective. Feel free to let me know if I missed anything.

Gender

Mando'a is a gender-neutral language. It does not discriminate between mother and father, there is just buir: “parent.” There is no differentiation between brother and sister; they are both called vod. Nor is there any difference between men and women; if you wear the armor, you are mando'ad, regardless of your sex. This is most relevant to the average sentence by way of the singular 3rd person pronoun, kaysh, which means he/him/his, she/her/hers, and they/them/theirs. It’s a workhorse of a word, but context does more than you’d think to convey meaning. Trust to context .

As a result of this, Mando'a is a very friendly language to trans and intersex people as well as women.

Note: there are words for man/woman/male/female, but they’re usually used in medical or technical contexts, or whenever you need to specify sex (which is rarer than you think, I guarantee). The assumption is that if you were to walk up to a Mandalorian and call him a man instead of a person, you would be seen as rude.

Of course, the ideal of the language and the reality of how KT constructed it come into conflict. It’s not really relevant to this post, but someday I might write something up about KT’s inadvertent sexism

Word order

Nouns do not have a grammatical case in Mando'a. Instead, they are defined (i.e. recognized as subject or object) by their position in the sentence, not by changing inflections. Thus, word order must be subject-verb-object.

In English, verbs and subjects can (sometimes) be switched around - “ate she the cookie” and “she ate the cookie” mean the same thing. That’s not always the case for Mando'a. “R'epa kaysh uj'alayi” can mean “they ate the uj cake,” but it can also mean “(they) ate their uj cake,” as kaysh means both “they” and “their.” It’s a pretty fine distinction, and context would probably make the meaning clear, but it’s a quirk of the language to be aware of.

Be aware also that while verbs and subjects can be switched around, subjects and objects cannot. “She ate the cookie” and “the cookie ate her” are two very different sentences. Note: it is possible to say in archaic or poetic English that “the cookie ate she” and still have it mean “she ate the cookie.” But again, as Mando'a does not discriminate between she/her, it cannot be used in this way. “Uj'alayi r'epa kaysh” cannot be understood to mean “kaysh r'epa uj'alayi.” The sentence must be constructed with the subject before the object.

(Subject-object-verb isn’t possible, either. “Kaysh uj'alayi r'epa” is a somewhat confused sentence - “they the uj cake ate” could mean either they ate the cake, or that the cake ate them! In Mando'a, it’s best to err on the side of subject-verb-object, and let other, more inflected languages play with word order.)

Adjectives, meanwhile, can go on either side of the noun they’re describing. “Jate uj'alayi” is just as correct as “uj'alayi jate.” As far as I’m aware, the same is true of adverbs and their associated verbs, but prepositions, like in English, must come before the object (hence the “pre-” in their name). You cannot “sit the table at” in Mando'a any more than you can in English.

Dropped words

Mando'a is a fairly terse language; like Russian, it drops definite articles (the) and indefinite articles (a, an). “Ad gaanade besbe'trayc” translates literally as “person picks weapon,” but can be understood to mean “the person picks a weapon.” An exception is when an article is added for emphasis. “Mand'alor te Solyc”–Mandalore the First. “Nayc, ru'sirbu eyn buy'ce, ne'birov!”–“No, I said a helmet, not many!”

Another commonly dropped word is any conjugation of the verb cuyir, “to be.” “Kaysh verd” translates literally as “they warrior,” but is understood to mean “they are a warrior.” An exception is when it’s used as an infinitive, such as “Ni copaani cuyir verd”–“I want to be a warrior.”

Pronouns can also be dropped, but it depends heavily on context and whether your listener will understand.

Of course, these are more what you’d call guidelines than actual rules, so the speaker can break them if they want. “Kaysh cuyi eyn verd” is absolutely correct, and especially for new speakers, can be helpful. Just be aware that these words will be absent in common use.

Conjugation

Every verb comes in two states: an infinitive and a conjugation. An infinitive verb can be indicated in English by the presence of “to” in front of it. “To eat,” “to sleep,” “to want.” A conjugated verb is indicated by 1) a change in the verb’s spelling (usually), and 2) the presence of a subject noun to construct a basic sentence. “I eat,” “she sleeps,” “we wanted.”

Mando'a conjugation is pretty simple. The infinitive of the verb “to be” is cuyir. To conjugate it, you simply remove the -r at the end of the word. “Ni cuyi”: I am. “Gar cuyi”: you are. “Kaysh cuyi”: he/she/they is. “Ni copaani cuyir verd” uses both a conjugated verb and an infinitive verb in the sentence. “Copaani” is conjugated from copaanir and means in context “I want.” Cuyir is left unconjugated, and thus means “to be.”

There are other conjugations, especially in KT’s phrases; most seem to take off the -r as well as the vowel preceding it (e.g. “cuy ogir'olar). This can probably be handwaved as a dialect or slang, the way English speakers sometimes say “gonna” or “gon’” instead of “going to.” But iirc, the way KT explained it on her website before she took it down was that dropping just the terminal -r is the “official” way.

(My biggest beef with mandoa.org is that they don’t always specify parts of speech, so there’s a HIGH risk of confusion. Take baarpir, “sweat.” It ends in -ir, so it looks like it could be a verb, but it’s actually a noun - not that you’d know, because the Mando'a Database doesn’t say. It’s not the best resource. Except for how it is. Sigh.)

Tenses

A grammatical tense indicates when, in time, the action of a verb is performed. Present tense means a verb is being done now, in the present. Past tense means it was done in the past, future tense means it will be done in the future, and so on. Each tense is marked by a different verb conjugation; in English, you can see it in “I eat,” “I ate,” “I will eat,” “I used to eat,” etc. Many languages have incredibly nuanced conjugations for speaking about when events will or have happened - Spanish has leo, leí, leyendo, leía, leería, leeré, lea, and probably six dozen others that I can’t remember, all conjugated from “leer,” and all to indicate different times reading can occur. English, on the other hand, technically only has two tense conjugations: past and present: “eat” and “ate.” All other tenses are indicated by affixing words like “will” and “would have.”

Mando'a is similar. In Mando'a, there is technically only one tense: present tense. Verbs are conjugated in present tense, and prefixes are attached to indicate different tenses. For past tense, the prefix is ru- (or r- if preceding a vowel). “Ni copaani” means “I want,” but “Ni ru'copaani” means “I wanted.” For future tense, the prefix ven- is used. “Ni ven'copaani” means “I will want.”

There is also a command prefix, ke- or k-, which, when applied, makes a verb into a command or order. “K'atini!” literally means “endure!”, but colloquially it’s closer to “suck it up!”

The last tense isn’t exactly a tense. “Tion” is the interrogative prefix; when it is at the beginning of a sentence, it indicates a question is to follow. “Gar r'epa” is “you ate,” but “tion gar r'epa” means “did you eat?”

Mando'a lacks any other tenses. As such, it’s a direct, somewhat time-insensitive language compared to English. Not all sentences are directly translatable; you may have to tweak your phrasing to accommodate.

Plurals

Plurals are pretty straightforward. To make a noun plural, you add an “-e” if it ends in a consonant, and a “-se” if it ends in a vowel. Vod becomes vode; copad becomes copade; aruetii becomes aruetiise; buy'ce becomes buy'cese. Three exceptions are ad'ika, ba'vodu, and gett, which become ad'ike, bavodu'e, and gett'se, and they can be explained as linguistic drift: first it was ad'ikase, but people gradually shortened it until ad'ike became the “official” pronunciation.

Possessives

I’m copy-pasting this from another comment I made because it’s a good description:

Possessives in Mando'a work by attaching the word be, which means “of,” as a prefix to the possessor, not the possessee. So you’d say “alor be'Ricky,” basically “the boss of Ricky,” or possibly “be'Ricky alor,” so long as it doesn’t confuse the meaning of the rest of the sentence. A rarer way (so says mandoa.org) is to attach it like a suffix, i.e. “Rickyb alor,” the way possessives work in English. It doesn’t make much grammatical sense (“Ricky of boss”??), but Mando'a plays fast and loose with grammatical structure anyway and common usage could normalize it. A third way is to attach the possessed noun like a suffix to the end of the possessing noun, so “Ricky'alor”–but that seems like a recipe for confusion to me. You could either mean Ricky’s boss, or that Ricky is the boss. It probably works better with places or things than with people: Ricky'yaim is pretty inarguably Ricky’s house, not that Ricky is a house :P Like everything in Mando'a, it’s hella dependent on context.

When in doubt, use “alor be'Ricky.” It has the least chance of confusion.

All that said, the sentence [“My brother Ricky is a smelter, his boss is a master smelter”] uses a pronoun, so you’d say “Ner vod Ricky naur'ad, kaysh alor naur'alor,” with kaysh meaning the possessive “his.”

The beten

The beten (Mando'a for “sigh”) is the apostrophe you see hanging out randomly in the middle of words. It doesn’t have the same function as, e.g., the apostrophe in Hawai'ian, which marks a glottal stop and vowel rearticulation; rather, the beten indicates where words or affixes have been joined together. Aside from words like aay'han or ta'ayl where KT’s orthography is irregular, it isn’t pronounced at all. Unless you want to.

As far as I can tell, the beten is used half-assedly according to personal preference. Burk'yc, “dangerous,” has it, but aruetyc, “traitorous,” does not. There is no real reason for this that I can see, other than (Watsonian) different dialects and spelling traditions got mashed together when Mando'a was formalized, or (Doylist) KT forgot about it or didn’t like the look of it. So don’t worry if you’re using it right. “R'epa” sounds the same as “repa” when spoken aloud, and if it’s in text it’s easy enough to parse.

Pronunciation

Pronunciation of Mando'a is a grab-bag, mostly because KT wasn’t very good at orthography. My recommendation: pronounce words the way you feel comfortable, and chock up any differences to dialect.

Some more in-depth discussion on the topic can be found here and here.

“Small” words

This isn’t precisely grammar, but I’ve found it’s helpful to have a list of small words like articles, conjunctions, and prepositions handy in one list, because they tend to get lost in mandoa.org’s search feature.

Bal: and

A-, al-: but (usually attached as a prefix, e.g. "a'solus,” but one; “al'elek,” but of course)

Ra: or

Bid: so

Balyc: also

Meh: if

Sa: as, like

Shi: just, only

Ori: big, more, very

Kih: small, less

Birov: many

Ori'sol: many

Kisol: few

An: all, every

Naas: nothing, none

Shya: than

Elek: yes (shortened to “lek” for “yeah”)

Nayc: no

N-, ne-, nu-: anti-, un- (negative prefix)

Bah: to (dative)

Jii: now

Vurel: ever

Ratiin: always

Draar: never

Ogir: here

Olar: there

Tion: what (interrogative prefix)

Tion'tuur: when (“what day”)

Tion'ad: who (“what person”)

Tion'jor: why (“what reason” from “jorbe”)

Vaii: where (potentially also “tion'taap,“ meaning “what position/location”)

Eyn: a, an

Haar: the

Te: the

Ni: I, me

Ner: my, mine

Gar: you, your

Kaysh: he/she/they, his/hers/their

Mhi: we, our

Val: they/their

Bic: it

Ibic: this

Ibac: that

Anay: every

Naasade: no one, nobody (“no people”)

Anade: everyone, everybody (“all people”)

Ash'ad: someone, somebody

Mayen: anything

O'r: in

Dayn: out

At: to, toward

Teh: from

Be: of

Ti: with

Ures: without

Bat: on

Chur: under

Sha-, shal-: at (used as a prefix: "sha'bral,” at fort; “shal'yaim,” at home)

Par: for

Vurel: ever

Jaon: over

1: solus

2: t'ad

3: ehn

4: cuir

5: rayshe'a

6: resol

7: e'tad

8: sh'ehn

9: she'cu

10: ta'raysh (“two fives”)

11: ta'raysh solus

20: ad'eta

30: ehn'eta

40: cur'eta

50: she'eta

60: rol'eta

70: tad'eta

80: shehn'eta

90: shek'eta

100: olan

500: raysh'olan

1000: ta'raysholan ("ten hundreds”)

5000: sh'eta'olan

451 notes

·

View notes