#but the collector would be a much more relevant antagonist in a story based on Labyrinth i think lol

Text

[ID: two pieces of digital fanart depicting Luz and Belos from the owl house dressed as Sarah and Jareth from Labyrinth (1986), respectively. They're wearing the costumes from the hallucination/ballroom scene. In the first piece Luz stands in the foreground with her skirt bunched in her fists, facing towards us but looking at something out of frame. She has a necklace of her egg palismen and a rod of Asclepius hairpin, and is wearing her white vans under her ballgown. Belos stands behind her in shadow, looking down at her and holding up a light glyph. The background is black. The second image is the same piece except with no shading, more vibrant colours and a purple background. End ID] @toh-described

🦉💫Don't tell me truth hurts little girl/Cause it hurts like hell🔮🌟

Labyrinth au!! Honestly surprised I've never seen one of these before?? feels very fitting. But I guess I'm the only one w/ this specific brainrot cocktail lol

(DO NOT TAG AS SHIP OR I WILL EXPLODE YOUR EYEBALLS💥)

#the owl house#toh#luz noceda#luz toh#belos toh#philip wittebane#i do have actual thoughts and (traditional) sketches to flesh this out into a full on au#luz and sarah are very different protagonists so it's fun to switch up the labyrinths design and narrative function to reflect that#if the labyrinth in the movie is trying to teach sarah to be grateful for what she has (lose moral cause this movie has -20 story)#then Luz's labyrinth would be a lot more of a ''give into temptation'' style test ala witches before wizards#overall very similar to the ballroom scene (hence why i took inspiration from it for this)#(also sparkly outfits <3)#I'd probably put the collector as jareth instead of belos as well?? i drew him hear bc I thought he'd look cool juxtaposed w/ luz#but the collector would be a much more relevant antagonist in a story based on Labyrinth i think lol#he'd have stolen king away after luz proclaims he'd be better off without her and she has to get him back yknow?#meanwhile the collector tries to lure her into giving up by crafting a fantasy world to tempt her#but of course she keeps going. make some friends. do some trials. you have no power over me. david bowie dance party. etc#it makes sense to me <3#anyway. Tumblr pls let these images be a decent size on dashboard <3

609 notes

·

View notes

Text

Films I watched on The Criterion Channel streaming service (part 1):

Pather Panchali (1955)

Pather Panchali is the directorial debut of Satyajit Ray, and I’ve never seen a film from India before. I decided to watch it after seeing an Akira Kurosawa quote that read, “Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.” Possibly the most glowing remark you could say about a film. Anyhow, this is the first of the quote-unquote “Apu trilogy”, named so for following the life of Apu, a character who is born in this film. Apu doesn’t get to do a hell of a lot, being just another part of an ensemble cast, it isn’t until the next two films that he begins playing a major role.

I’d describe Pather Panchali as mostly being a film about life. There is no major defined conflict, it just depicts Apu and his family just trying to do what they can to survive in the harsh world that they find themselves in. Minor spoilers ahead but this is one of those films where I watched it mostly to see what was coming up more so than because I was invested in what was happening at the moment. I won’t say specifically why but I didn’t quite ~get~ what the big deal was until literally the last 20 minutes of a film that was nearly two hours long. This is a film that winds up before punching you squarely in the face, is all.

The 400 Blows (1959)

First one I watched with @bone-collector-cryptid. The 400 Blows is the directorial debut of Francois Truffaut, and a major film in the “French New Wave”, which having done some brief research, was apparently a movement in which several French film critics and commentators basically decided to pick up a camera and show people how it’s done. This film specifically follows Antoine Doinel, a mischevious-but-not-malicious young boy, where, no matter his attempts to do better, can’t avoid the ire of his parents, teachers, police officers, etc., his life being a seemingly downward spiral of misery.

Come and See (1985) is objectively more grueling, but for me personally this was far and away the most difficult one of these for me to watch, so much so that it felt like I was strung up with my eyes open Clockwork Orange style, largely because I personally dealt with a lot of the same shit Antoine does in this film. While I would regard it as a great film, I don’t think I’d literally ever be able to watch it again, yeck.

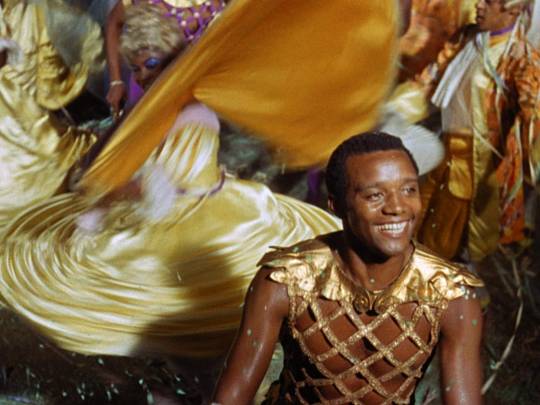

Black Orpheus (1959)

Second one I watched with @bone-collector-cryptid. Never seen a film from Brazil before. Black Orpheus is one of those films that makes you feel like you’re seeing in color for the first time. Immediately it opens up and just dazzles with how blue the sky and ocean are, how green the grass is, and all the gold and purple and whatnot that adorns everyone’s outfits. Black Orpheus transposes the Greek story of Orpheus and Eurydice (to say it is “inspired by” is more accurate than to say it is “adapted from”) to Rio de Janeiro with a seemingly entirely black cast (some nonblack people get minor speaking roles here and there). Orpheus is a guitar player who is stuck in an upcoming marriage that he’s not very thrilled about, Eurydice has traveled to stay with her cousin, Orpheus’ neighbor, to escape a man dressed as Death who is plotting to kill her, their fates intersect, and if you’re familiar with some version of the original story, you have a pretty solid idea of where this one will end.

Black Orpheus mostly struck me with just how lively it is. It is an ultimately bittersweet-at-best story, but seeing EVERYONE sing, dance, play music, dress as extravagantly as they can? It gets to you, in a good way. I also enjoy its interpretation of events of the story; the fact that the two characters share names with their Greek predecessors is noted and an active plot point, everyone is on the joke as it were, and it’s all the better for it.

The Sword of Doom (1966)

Tatsuya Nakadi is quickly becoming one of my favorite Japanese actors. I’ve seen him play the antagonist in many of Akira Kurosawa’s films, such as Yojimbo (1961), Sanjuro (1962), or Ran (1985), but in this film, directed by Kihachi Okamoto, he’s at his most malicious, basically playing a slasher villain in feudal Japan. Nakadai is Ryunosuke Tsukue, a samurai who seemingly only exists to deal out violence and death everywhere he goes in the process of improving his skills, with all the other characters caught in the web of violence he spins. Nakadai has often been defined by large expressive eyes, and in this film there’s no soul behind them.

The Sword of Doom is effective but something of a mess, largely because it was supposed to be the first of a never-produced series, so now there’s a ton of heavily telegraphed plot points that never come to fruition because hey there are no sequels to this. It makes for a pretty frustrating watch when you get to the end if only because you don’t get an ending (I would say spoilers but there’s nothing to damn spoil), so your mileage with this one will be based on how much you are invested in a journey up to that.

The Face of Another (1966)

Nakadai again! Of all the films I saw here, this is one I can picture becoming my favorite at some point down the line (even though Black Orpheus and Come and See are the ones where I actually went out and bought physical copies after seeing them). Watching The Face of Another is like walking into a hall of mirrors, or a cave where you can dimly see the light from another entrance off in the distance. Nakadai plays Okayama, a man whose face was lost in an accident forcing him to completely bind it up. Okayama needs a new face because without one he has no soul, and when he does get one, he becomes a new person conversely. Something something “WOW this is more relevant now than ever thanks to the Internet” blah blah blah.

I really could not tell anyone the exact details of what happens in this film or what the larger purpose of its story is, basic stuff like why there’s a subplot involving a young woman with radiation scars across half her face were lost on me. I just kept watching for the raw sensation of it all, it’s images and music absorbed far me than any other film I’ve ever seen before or since.

(Part 2 coming in a reblog.)

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

there isn’t a new chapter but i feel like I should still...write things

Fool that I am, I thought that since there wouldn’t be a chapter this month, I could just quickly type up a post about some hnk things that have been on my mind, but haven’t been immediately relevant to the new chapters. Easy Peasy.

Now it’s 5,000 words later, I’ve started ranting about geology instead of my usual literary bullshit, a couple cookie recipes have snuck their way onto this word document, and the Euclase section has ballooned far beyond its original scope.

Anyway, click the read more if you want to see the following topics:

Hot takes about Euclase

I attempt to psychoanalyze Cairngorm’s fashion choices

Visual symbolism from the cover of the artbook

What type of microcrystalline diamond aggregate is Bort anyway? ft. the etymology of Bort’s name

Crazy snail theory

Since Euclase is a bit of a hot topic at the moment, I figured that I might as well expand a bit on my thoughts towards them. Somehow, I ended up writing a big ‘ol essay. Then I erased most of that essay. But there were some good bits in there, so here’s what I thought was worth salvaging. First though, I should lay my cards on the table, and explain why I’m not on team Euclase Did Nothing Wrong.

In the days following the release of chapter 71, I’ve heard a couple people say that this line:

was not translated with the appropriate nuance, and that Euclase wasn’t blatantly saying “lol, I’ve found their weakness.” However, the fact that Padparadscha regards Euclase’s words as emotional manipulation in the very next scene indicates to me that that’s still a probable reading of Euclase’s actions, even if they’re not being as unsubtle about it as the translation implies. I don’t know much Japanese though, so I can’t really comment on any translation issues that may or may not have occurred.

I think my sticking point with Euclase is that I have trouble buying that they’re acting in good faith or that they’re really committed to the ideals they’re espousing. Granted, most of what they’ve been saying and doing seems reasonable, especially compared Phos’s short-sighted flailing. They haven’t displayed any malice, and they’ve at least paid lip service to wanting positive change and demonstrating pro-social behavior.

But here’s the thing: if they truly value change, and they simply want to go about effecting positive change in a way that’s more sensible than Phos’s bull-in-a-china-shop strategy, then why are they so consistently reactionary? (I mean this in the most neutral sense of the term, btw.) They didn’t value an equitable relationship with Kongou until Phos made it impossible for the Kongou-centric monarchy to continue. They felt no urgency towards Cinnabar’s plight until they became useful in warding off the moon gems. They showed no concern for Phos’s crippling lack of self-esteem until they could use it to try and persuade Phos to defect to their side. Even though they have reputation among the other gems for being kindhearted, from what I’ve seen, they’re only ever as kind as is absolutely necessary to maintain group cohesion. The only time they’ve been considerate of someone else’s feelings in a proactive manner is with Dia, specifically regarding their issues with Bort. And since those two are the gems’ strongest non-comatose defenders, it’s prudent for Euclase to concern themselves with their issues.

Like, compare Euclase and their partner’s respective reactions to Phos in chapters 21 and 22. The story goes out of its way to show that Jade doesn’t mob Phos like the other gems, and they express concern over Phos’s insomnia. Euclase meanwhile, has no compunctions about ganging up on Phos with the others, and only apologizes when they need to ask a favor of them. I kind of expect a bit of tactlessness from the other gems, because most of them, on top of being single-minded, are implied to be pretty childlike on account of the highly static society they live in. And even those who aren’t very childlike kind of don’t have their shit together. But since Euclase has positioned themselves as wise and compassionate authority figure, that sort of thing stands out. And when they’ve cultivated a reputation among the other gems for being kind, it’s really off-putting when the narrative drops hints that that kindness isn’t sincere.

Couple all that with Padparadscha’s wariness towards them and that creepy face they made in chapter 60 and my predominant emotion towards them is

Which isn’t to say that I hate them or anything. To the contrary, I think that it’s valuable that their perspective--that of someone who is stalwartly on the ‘society’ side of the whole ‘individual vs society’ theme that the manga has going on—is a valuable one to acknowledge in the story. Furthermore, I find them to be quite the interesting character at this point. They’ve come a long way from their initial role as “that one minor character who follows Jade around.” I also find characters who are in some way secretive or two-faced to be a lot of fun because I get a kick out of trying to wade through the miasma of subtext and half-truths to try and get to the core of a character (looking at you, Craig-Greg.) Anyway, in Euclase’s case, I don’t even think they have bad intentions; but at the moment, the impression I’m getting is that they only value other people insofar as they can contribute to the maintenance of society, whatever form that society takes, rather than seeing society as something that should exist for the sake of enriching the lives of inherently valuable people. Despite the fact that Euclase is a staunch team player, I’m gonna go on record and say that I don’t think they care all that much about other people, they’ve just come to the conclusion that being cooperative and not rocking the boat as a general principle is the most rational way for them to go about their life.

If at some point in the future Euclase demonstrates that this isn’t their mindset, then I’m prepared to eat humble pie and admit that I was interpreting all their actions in the most cynical light possible and jumping to conclusions from there. But for now, I am Mr. Krabs.

Getting away from “It’s about ethics in gem society” for a moment, I suspect that, unlike a lot of the other gems, Euclase isn’t really coming from a place of willful ignorance. They’re not incurious and their words and actions have been quite deliberate. I think that they know—or have at least inferred—some truths about their world that a lot of the other gems look away from. Their oft remarked fondness for statistics might have given them insight into some discrepancies in the narratives they’ve been fed by Kongou. For example:

They’re probably well aware of the fact that no one on the moon has ever come back, and that if they themselves are captured, they’re gone for good. (According to Aechmea this wasn’t always the case; but it’s quite possible that the gems who were returned to earth and promptly recaptured lived before the gems started keeping written records as well as before any of the current characters were born.)

If we compare the number of old gems to the number of young gems to the number of middle-aged gems, it’s clear that the old group is the smallest in number, and that most of the gems who make it to old age don’t patrol often for one reason or another. Even though the gems go about their lives under the assumption that if they’re careful, they’ll never be caught by the Lunarians, that assumption is clearly not based in reality. And Euclase, who apparently knows how old each gem is down to the day, is probably well aware of how illusory their immortality really is.

What I’m getting at is this: they’re likely one of the few gems who have wrapped their head around the concept of death, and like all the other gems who’ve come to understand that they’re not as immortal as they’ve been lead to believe, this knowledge has informed their outlook on life and their actions. But while someone like Phos has taken a carpe diem approach to dealing with the fleeting nature of life, it seems to me that Euclase responded by maneuvering themselves into a position where they never have to take risks and, thus, never need to die. As one of the little character intros mentioned, Euclase is skilled enough for any job, but the job they’ve chosen is one that apparently allows them to avoid patrolling and stay out of danger.

Something I find interesting which I expect to be brought up in the story later is Euclase’s insecurity about their brittleness, which was briefly mentioned in chapter 8. To expand on this, Euclase has three planes of cleavage, one perfect and two distinct. This aspect is actually something they share in common with Phos. Euclase, like phosphophyllite, is considered among gemology nerds mineral collectors to be a beautiful mineral that would make for great jewelry...if it wasn’t so rare and brittle. Both of them also have names that reference their brittleness--euclase means “easily broken” and the -phyll part of phosphophyllite references its perfect cleavage.

Since many of the gems have one or more aspects of their characterizations based on the physical properties and/or cultural associations of their minerals, and since breakage is a major motif of the work, I think there’s probably significance to the fact that Ichikawa decided to make a gem so thoroughly associated with brittleness into a major character. That’s how it is with Phos anyway. To paraphrase a bit, Ichikawa said in this interview that phosphophyllite’s much lauded beauty and rarity juxtaposed against its unsuitability as jewelry was the inspiration behind Phos as a character being bold yet perpetually ineffectual (and of course very, very breakable, both literally and figuratively.)

So, this character, who is shaping up to be an antagonistic(?) force has a similar—and thematically relevant—existential condition to our protagonist, and they deal with it in a strikingly different way. It’s a bit early to say where this element of the story is going to lead, but it’s worth keeping an eye on.

As I’m typing this, I’m starting to wonder if the reason why Euclase misinterpreted Phos’s words in chapter 70 as insecurity about their hardness is because Euclase themselves is insecure about their brittleness. In fact, that might also be the reason why they didn’t show themselves in chapter 70 until everyone was down and out, and why their overall plan involved shooting first and asking questions later. The chance of breaking and showing weakness—either literally or figuratively—isn’t one they want to take, even at the cost of a lot of casualties/toxic mercury spills. Additionally, when the Lunarians reported that they observed no changes in the earth gems’ behavior, Padparadscha comments that it seems like something Euclase would do, and doesn’t elaborate any further. I think this aspect of their character is what Padparadscha was getting at, that Euclase is loath to show weakness, and goes to great pains to never be the first one to blink.

Going back to chapter 8, they also talk about how the gems’ immortality predisposes them to be ignorant of danger, and how they somewhat envy the bugs and plants that can react promptly to changing stimuli. At that point in the story, it just seemed like one wistful observation on immortality among many, but looking back on it, it may have been just as much a window into Euclase’s anxieties as that line about their brittleness right after. For someone who wants to organize the world around them and dislikes uncertainty, it must be frustrating for them to imagine that some inherent aspect of their nature predisposes them towards ignorance.

To pull back a bit, I imagine that the point of making statistics Euclase’s beloved hobby is to help set them up as a foil to Phos. It’s a way to allow them insight into the flawed and tenuous nature of their society and their own existence without having them actually go out into the wide world to experience those answers for themselves like Phos does, since they’re not the type who’s willing to take risks. So unlike say, Melon or Hemi, they’re not wallowing in their comfortable yet stagnant existence because they’re willfully ignorant and simply don’t want to inconvenience themselves. Instead, they’ve spent their life running cost-benefit analyses and have come to the conclusion that they should maintain the status-quo to the best of their ability and avoid putting themselves out there. It may seem like a distinction without a difference, but I think that’s what Ichikawa is going for. Not to mention, it’d be kind of lame if everyone who decided to go against Phos and stay on earth was doing so out of incurious stubbornness or simple concern about the logistics of Phos’s plan. For one of the gems to oppose Phos due to irreconcilable differences in worldview seems a bit more meaningful to me.

So, the core of the conflict between Phos and Euclase is that Phos finds value in risking failure as a means to finding something better, while Euclase believes that if they can simply play the system forever, they’ll never have to reap the negative consequences said system doles out. This kind of goes without saying, but I don’t think the narrative is going to side with them in the end; looking at the story as a whole, I doubt that “If you keep your head down and play your cards right, you’ll be able to avoid suffering,” is a conclusion it wants to reach.

But much like the rest of the cast, Phos has forced Euclase to change. See, as much as they like to control the environment around them, they don’t like to let on that they’re doing so. To me, their blurb on this page indicates that the reason they stick to Jade and subtly direct their actions is because it allows them to micromanage everything to their heart’s content while letting someone else take on the nominal position of authority and all the attention and responsibility that comes with it.

But now that Kongou has ceded power, Euclase doesn’t have the luxury of pretending to be middle management anymore. Since no one else was willing to step up to the plate, they had no choice but to do so. And now that the gems are split in two, Euclase has been forced to publicly stand for something. Even if they’re trying to mitigate possible risks, they’re still operating well outside their comfort zone, and given that this manga is a veritable meat-grinder, it’s only going to get harder for Euclase to keep their world in order.

To sum it all up: yes, Euclase is a snake. But they’re, like, a complicated snake. A snake whose character flaws spring forth from very real insecurities. A snake who just wants to spend their days lounging on a comfy heating pad without having to worry about Actual Chaos Elemental Phosphophyllite mucking everything up.

(Ichikawa please validate my interpretation or else I’ll become Boo-boo the Fool.)

Anyway, Euclase isn’t the only character insecure about their brittleness…

Naturally, I continue to have thoughts regarding The Artist Formerly Known as Craigory. There are times where I wish I had gotten attached to a more respectable character, but honestly where’s the fun in that? I stan disasters!

I mentioned in my last write-up that the glove Cairngorm is now wearing over their left arm pretty blatantly displays their desire to cover up the part of themselves that’s prone to breaking, both metaphorically and literally. But after some thought, I’ve realized that their entire wardrobe is full of AnxietyTM. Here’s a few of my observations.

They started off their foray with avant-garde moon lingerie with a small transparent shawl which has, a month later, become a full-body veil. It seems to me, on a purely visually symbolic level, reminiscent of their situation with Ghost. Like, if I were Ichikawa, and I were looking for a way to symbolize their existential plight in clothing form, that’s how I’d do it. If I were to try to decode the meaning behind the evocative imagery, it’d be this: they’ve become trapped again, and are still being blocked from the freedom and the engagement with the world that they desire—symbolically in the sense that they’re interacting with the world through a veil, and literally in the sense that Aechmea seems to be, uh…strongly discouraging them from leaving their room, or doing things in general.

Cairn, please love yourself and get as far away from this creep as possible; I’ve got a sinking feeling that he’s going to cash in all those red flags he’s been setting off sooner rather than later.

Then there’s the matter of Cairngorm’s ongoing quest to find the Worst pair of shoes. See, Cairn started their love affair with terrible shoes long before chapter 68.

They’re not as ostentatious as say, the banana-peel crocs but…I mean look at them. These may as well be pointe shoes. Anyway, comparing these with their more recent…shoe decisions, I can’t help but think they might be a bit insecure about their height? (And in case any of you guys didn’t see it, this omake explicitly spells out that they’re shorter than the other gems.)

Even though they’re at most a couple centimeters shorter than the others, they seriously overcompensate for it. I think that for them, the slight difference in height is a painful reminder that they’re not fully formed like the others are, which has lead them down the path of…dreamfoam platform high-tops.

Getting back to the glove, chapter 44 contained a lot of subtext that indicated that they’re insecure about their finicky arm, and possibly about their finicky inclusions in general. The whole buildup to Phos’s head being stolen is full of dumbass decisions from both of these clowns, but on Cairn’s side, they contributed to the whole fiasco by hiding the fact that their arm had been strained past its limit, and insisting on taking down the vessel alone in spite of that fact. I’ve talked a bit before about how embracing or rejecting one’s weakness and impermanence is a major motif of this series, so the fact that Cairngorm consistently tries to hide the part of themselves that keeps breaking is…noteworthy, as is the fact that their most obvious attempt to do so in chapter 44 ended very badly.

Which got me thinking, what if that’s also why they started wearing long sleeves? It might be possible that the long sleeves on their winter uniform served the same purpose the glove does now--to cover up their left arm. We saw their bare arms in chapters 68 and 69 and it looked fine then, but what if, say, fractures appear on their left arm on a regular basis, and they wore long sleeves in order to cover it up?

To sum it all up, the aspects of themselves that set them apart from the other gems are all things that they subtly act like they’re ashamed of, and their choice of clothing reflects this.

I’ve already made a couple of posts about the cover of Pseudomorph of Love, but I felt like staring at it again and reporting my additional findings.

Something I noticed is that while the other characters’ broken pieces are placed right next to themselves, Phos’s pieces are scattered over the entire cover, usually lying on top of one or more of the other gems. I have circled them here, with my peerless image editing skills.

If I were to take a guess at what this visual symbolism is trying to say, I’d say it’s that by changing and breaking, Phos leaves an impact on others. At their very best, I think Phos breaks other people out of their bad habits and learned helplessness. As Phos rushes forward, they also drag others out of their personal hells, sometimes intentionally, sometimes inadvertently. Needless to say, they don’t always live up to these ideals, but that’s the general direction they’re headed in.

(Hey guys, do you think the fact that Phos’s hand is caressing their own face is foreshadowing that one day they will let go of their self loathing and learn to love themselves? Because I want that to be the case.)

Oh, and Cairn is indeed missing The Left Arm of Conspicuous Foreshadowing here too. The break is even at the same angle. If it turns out that nothing else happens to that arm for the rest of the story then I’m going to be so embarrassed because I have gone full pepe silvia over it.

Pictured here is Ichikawa making me cry by sneaking the foot Antarc left behind into the illustration.

The only other gem whose parts have managed to travel across the cover is Dia, whose hand is next to Bort. And I’m sure that it’s Dia’s because it’s a right hand and Euclase’s right half is blue in this illustration, and it can’t be Antarc’s either because all of Anatarc’s pieces are overlayed with a shimmery, watery reflection. Make of it what you will.

At this point, I’m going to take off my literary hat and put on my middle school geology phase hat. Bort, how can I possibly bless your marriage to Cinnabar if I’m not sure what arbitrary classification of diamond you fall into?

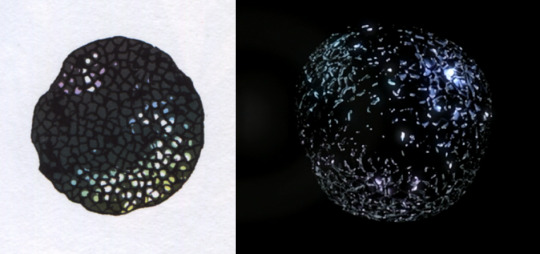

So, bort is a rather ambiguous term, and can refer to basically any diamond that isn’t fit to be used as jewelry. But Bort the character is not so non-specific. They’re supposed to be an aggregate of microcrystalline diamonds, and the thing is, microcrystalline diamond aggregates are considered notable enough that they get their own names. So while the term ‘bort’ does encompass these specimens, it’s a bit imprecise.

Microcrystalline diamond aggregates can be roughly grouped into four different varieties: framesite/stewartite, ballas, carbonado, and yakutite.

Ballas, also known as shot bort, are microcrystalline diamonds with a radiating, fibrous habit that form spheres of various sizes. Despite being opaque, it sometimes displays a pearly luster depending on how heavily included a given specimen is. It ranges in color from white to gray to black.

Framesite is the name applied to most granular-to-microcrystalline diamond aggregates. It's usually black but I couldn’t find an exhaustive list of colors. Stewartite is the term for framesite that’s been magnetized as a result of magnetite intergrowths and inclusions.

Carbonado is the toughest and most mysterious form of diamond. No one knows how the hell it forms, and theories about its formation range from the transformation of irradiated hydrocarbons to supernova-genesis. These rocks are a hodgepodge of diamonds, graphite, and amorphous carbon. Carbonado is very porous and its component crystals are of a much smaller grain than either ballas or framesite. It is also further distinguished from its fellow diamond aggregates by a melt-like glassy patina that coats its surface. While most are just black, they come in a wider range of colors than other microcrystalline diamonds, including grey, red, brown or even some weirder colors like green, purple, and pink. There’s also some evidence that suggests it’s slightly harder than normal diamonds—at the very least, many a diamond-tipped sawblade has been ruined trying to cut into carbonado.

Yakutite is named for the location in Russia where it is found. It is characterized by its numerous lonsdaleite inclusions, and since it’s found in rocks that have undergone shock metamorphism, it is thought that yakutite forms via meteor impacts. So, this is pretty much the only variety of microcrystalline diamond we can rule out since I’m not seeing any meteor craters on the island.

At first I was thinking that since the inside of their hair is brownish red, and carbonado is the only one that comes in that color, they must be carbonado; problem solved!

But then I realized that the inside of Bort’s hair has never been colored that way in the manga, only the anime. In colored illustrations, the inside of their hair is iridescent like Dia’s, but with much more muted colors, so that it looks more like an oil slick or something and less like a rainbow. That could be an artistic representation of the glassy patina of carbonado, but it might also be the pearly layers of ballas. Framesite on the other hand is more likely to have a completely dull luster than either ballas or carbonado, so…one point against framesite I guess

One thing that indicates they might be ballas is how their mineral is represented in both the episode 10 eyecatch and in one of Ichikawa’s illustrations. The bort represented in these images has the spherical shape of ballas.

The most compelling argument for Bort being made of framesite is the fact that out of all the options here, framesite is the most likely to be referred to as simply ‘bort.’ Several sources I’ve looked at listed framesite and stewartite as being obsolete names for what is normally just called bort these days. This comes with a big caveat though.

While the scientific names of minerals are widely agreed upon and are consistent cross-linguistically, unofficial trade names are...not. For example, our Padparadscha probably wouldn’t meet the GIA’s standard for padparadscha sapphire on account of the fact that they’re pinkish-red with a bit of orange and a somewhat dark shade, rather than the GIA’s narrowly defined pastel salmon coloration. But despite the GIA’s current standard on what counts as padparadscha, they’d still meet the criteria for padparadscha found in historical literature on account of being a hunk of corundum that’s vaguely orange-looking. There are other gems in this series who exist in this gray area, but this post is getting pretty damn long so I’ll spare you poor readers the details.

What I’m getting at here is that if you look at the Japanese Wikipedia page for carbonado, bort is listed as a synonym. So even though they’re not typically used interchangeably in English, it looks like that’s not the case in Japanese. In fact, last spring this geology museum did an hnk themed event, and the rock they used to represent Bort was a hunk of carbonado, and this tweet they put out treats bort and carbonado as synonyms.

In carbonado’s corner, there’s Bort’s fight with Ventricosus. During said fight, chunks of their hair melted off from Ventri’s acid. But here’s the thing though: diamonds can’t be dissolved by acid, no matter how strong that acid is. If we generously assume that Bort losing some of their hair isn’t just a plot hole, then it may point to them being carbonado, since the graphite and amorphous carbon packed into carbonado is readily soluble in acid.

In conclusion, there is no answer and I’m slowly going insane. My mind is all out of Bort license plates. I’m leaning towards carbonado because of Bort’s galling lack of acid resistance and also because I think carbonado is a pretty cool rock.

Putting on my literary hat once again, I can’t help but wonder if the reason why Ichikawa went with the ambiguous bort over the other possible names was because of its etymology, which comes from the Anglo-Saxon gebrot, meaning fragment which is in turn derived from breótan, ‘to break.’ (A related cognate from Middle English is brotel, which became brittle in modern English.) Its cognates in other Germanic languages all seem to have meanings along the lines of ‘a break,’ ‘a rupture,’ or ‘a fracture.’ Another possible source of bort is the Old Norse brotna, meaning break. -Brot also shows up in a few other Old Norse words like Skipsbrot—shipwreck, Haugebrot—the destruction of a grave, and ísabrot, meaning oh-god-someone-please-take-my-dictionary-away-from-my-sinful-hands.

Ahem,

Out of all the possible names Bort could have had, they got one that references brokenness. I realize that this probably isn’t intentional symbolism, and I’m just shoving my interest in linguistics where it doesn’t belong, but I do think it’s a nice bit of serendipity nonetheless.

Okay, I promised you guys a galaxy-brained snail crack theory, so here goes: I’ve mentioned before that Variegatus seems to share a lot of parallels with baby!Phos, and that her name, which means multi-colored, could be said to describe Phos’s current state of being. It seems pretty clear that, on a metaphorical level, she’s connected to Phos. Well, what if that metaphor was literal, and ~somehow~ the inclusions from Phos’s arms and legs which were lost at sea ended up reborn as Variegatus, and that’s why she’s so Phos-like. The idea seems pretty absurd, but it wouldn’t be the first time Ichikawa has used someone’s body parts becoming their own sentient person as a plot device.

#houseki no kuni#land of the lustrous#*slams my face into an anglo saxon dictionary* will this help me understand hnk?

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our material world is defined and solidified by the movements of capital. In Pierre Bourdieu’s article “The Forms of Capital” he argues that capital crafts the “games of society”. All of our interactions, with objects, persons, or otherwise are concerned and comprised around our own personal capital accumulation (or lack thereof) and the way in which we choose to exercise it’s use. He does not spell out a solution for the phenomenon of social and cultural capital but merely states the ways in which they exist and the methods persisting that make certain power, influence, will is retained in a hegemony of wealth in the hands of the few.

Pier Paolo Pasolini was a novelist, philosopher, poet, activist, and most prominently a filmmaker in the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. Pasolini’s films were often distinctly sexual and provocative in a way few filmmakers could attest to, no one had the ability to ignite the tempers of both the intellectual right and left as Pasolini. He was a noted student of Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci, the influence of Gramsci’s work with cultural hegemony, historicity, and championing of consciousness for the proletariat had an undeniable impact on Pasolini’s work, but his semi-secret life as a homosexual man kept him from falling to easily under any labels as Italian Marxists often didn’t claim him as one of their members due to their homophobia.

His work is his own, difficult to equate to any filmmakers at the time or since, some have compared his filmmaking to that of the Italian neorealists, which seems a lazy assumption based on race and perhaps a collaboration with Fellini, because surely his work is too romantic, heady and occasionally cynical to be saddled with the baggage of that title. He films prostitutes, beggars, murderers, pimps, pedophiles, adulterers, bored monks, horny nuns and marxist crows as if they were saints.

Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922 – 1975) the Italian critic, novelist, film director and screen writer. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

In “The Forms of Capital” Bourdieu outlines the structures comprising our daily lives: the realm of cultural and social capital affirm, reaffirm and ultimately define our positions in society. Pasolini’s The Decameron, an adaptation of Giovanni Boccaccio’s seminal collection of 14th century Italian stories, aimed to destabilize this realm, this covering over of the culture of the proletariat which Pasolini would argue is a culture more honest, more true and perhaps more beautiful than that of the hegemony curated by the bourgeoisie. Pasolini’s The Decameron offers a comical, joyful, playful vision of youthful sexuality, subverting many of our assumptions about renaissance society, dangling the possibility that these characters may been more liberated than we because innocence could still exist, persisted and was celebrated. It had not yet been regulated to another form of capital but existed outside the realm of material exchange.

Following the receptive public and cold critical reaction to The Decameron and Pasolini’s following trilogy (Trilogy of Life encompasses The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, and, Arabian Nights, all resounding commercial successes as far as Pasolini’s overall career is concerned), the creator turned towards the present state of bodies while loosely adapting another classic work of Latin literature Dante’s Divine Comedy resulting in 1975’s Salò, Or the 120 Days of Sodom. Pasolini adapts these staples of world literature in an uncompromising and original execution, he reclaims them for the working class through language, performance, tradition and storytelling. Pasolini captured the degradation of substance, attempting to contaminate the forms of capital with the very freedoms it stripped from the masses: love, truth, clarity. The forms once innocent, can never be again, the history of capital cannot be undone, sexuality, food, art, revolution, morality are now reduced to mere tools of corporate fascism, of which we ourselves are its victims and proprietors.

Pasolini was no stranger to adaptation with The Decameron as he had already translated for the screen not only major works of literature in, Oedipus Rex, Medea, and The Gospel of St. Matthew but he also further explored his own published literary works in Accattone and Teorema. For The Decameron, however, Pasolini reworks both Boccaccio’s stories, muddying their structure and doing away with their framework.

In the original story a group of seven young women and three men attempt to escape the Black Plague ravaging their city and take refuge in the countryside for two weeks. They entertain themselves by telling tales. Over the course of Boccaccio’s text the ten refugees tell one-hundred stories, ten of which Pasolini employs in the film. The other half of the film is composed of ten original episodes inspired by Boccaccio’s tone and style, written by Pasolini himself. In Boccaccio’s version, a leader is chosen for the day to curate the stories around a certain topic of their desire.

One of the primary functions of Boccaccio’s work was not only to reflect on the current state of his time, the plague, religion, sexuality, but also to establish the virtues and ethics surrounding these topics for the coming generations, which for Boccaccio (and Dante) was the renaissance. These writers created immensely popular works that have been read and taught for centuries, not only as items of cultural significance, but much like the bible, became objects of moral foundation. Both the Divine Comedy and The Decameron are taught in private schools, higher learning institutions, taught to the few who dictate the needs of the many. This was particularly true of Pasolini’s era, as there was a stark gap in the education of the Neapolitan farmers he grew up around opposed to the wealthy bourgeois families he depicts in Teorema. If these same affluent children are reading these stories, internalizing their moral guidelines and proliferating them, there must be something corrupt if we have found ourselves in this current society of extreme disparity and division.

Pasolini if anything, reads The Decameron as an ode to the origins of the Italian elite that also belongs to them, “… he will use this text, ironically, to tear cinema away from the bourgeoisie, which has lost its ascendency as a historical force”. Pasolini’s The Decameron is an attempt to wrestle these texts out of the hands of the few and disseminate them back to the people whom the tales are about, the peasants, swindlers, youths, love-makers. The bonds of the forms of capital can be shattered only if we seek to take back the works from their perceived labels and pretensions by means of contaminating the original.

This contamination is a process of inclusion and exclusion, negating the intent of foundational novels, opposing their essential thesis, in order to reach more relevant truths with grander implications for our current existence in post-late-capitalist society, “…a devotedly antagonistic, as it were, cinematic imitato of the original”. Prior to an analysis of the content of contaminating an adaptation is the form, Pasolini furthers his inquiry into form by altering the language of Boccaccio’s text. This is most apparent in a scene where an elderly man sits in the streets reading to a crowd from Boccaccio’s The Decameron he quickly becomes frustrated with the flowery Tuscan dialect and throws the book aside speaking in his native Neapolitan language. If the forms of capital have any power which helps them to retain their divisive nature, their greatest tool is language, the language of the rich and of the poor may as well be taught as two separate classes, in some socioeconomic circumstances they are.

This scene has a meta-commentary undercurrent, in the spirit of the Dirty Projectors Rise Above rendition of the Black Flag album of the same name, Pasolini and this storyteller preaching to a crowd are recounting these tales from memory rather than the page, giving their creative license, new affirmative power over the original forms. This awakened authority begins with language, returning these stories to the people who comprise the content diminishes their stature as documents dictating the behavior of the masses and reemphasizes them as methods of expression, even revolution for the proletariat.

The most crucial indictment of the influential falsehoods concerned with the forms of capital are in the story of Ciappelletto, a murderer, thief and pedophile who finds himself dying in a town where no one knows him after being expelled from another town for rape, forgery and the aforementioned murder. He protects himself from these crimes by participating as a brute debt collector, the debtors often as conniving and vile as he. The film opens with him bludgeoning an unknown character, presumably a debtor, before throwing their body off of a ledge.

When he arrives in this foreign village Ciappelletto is gravely-ill, he’s well aware that these are his last moments for the world, he sends for a priest to absolve him of all his evil sins. Much of the comedy of this scene comes from the audience waiting to hear an honest confession from Ciappelletto in the eyes of his savior, instead he lies, filling the priests ears with an image of an honest, meek, frail and wholesome individual.

With this testimony the priest is brought to tears, blessing this man as a saint in the eyes of God. Ciappelletto dies only to have the church hold a massive funeral procession that raises him to the heights of sainthood. In life Ciappelletto suffered persecution, exile, he is bisexual, poor, ugly and lazy, he’s never been wanted anywhere. In death, however, he is made holy, not only redeemed in his lying but exalted. Whereas Dineo, one of the refugee-storytellers of Boccaccio’s Decameron insists that “the obscenity of his tales is a function of his obedience”, Ciapelletto’s obedience in death is a product of his obscenity in life.

The forms of capital are flimsy, bias and irrational if a man like Ciappelletto is able to reach such pillars of esteem. What strength other than maintaining a hegemony do the forms really have? Are the words of the church, governments in all their conglomerated wealth really enough to uphold goodness? This line of questioning is akin to that of Chaplin in Monsieur Verdoux; Ciappelletto and Verdoux may be ghastly, frightful men in their own regards but they are merely products of human nature reacting to a ghastly, frightful world around them. They harbor only a fraction of the malice that the cruel leaders of our world contain, for Ciappelletto it was kings and queens, for Chaplin the Hitler’s, McCarthy’s, the bankers, for Pasolini it was the capitalist, unwavering and ruthless who differed little from the fascist in their desire for total control. Ciappelletto manipulates the accepted moral exercises of society, social and cultural capital are malleable not only in their content but in their application to the individual, Ciappelletto understands that the material of capital is perhaps far less important than the perceived nobility or convenience of action within its stated bounds. He mimics Boccaccio’s intent while subverting it:

“Boccaccio offers an image of a self-regulating society, which articulates its own rules of comportment, and in which power is identified with, or is derived from, the delimitation of the sayable, the act of imposing a frame upon the field of narrative possibilities: the act of exclusion.”

Ciappelletto has excluded the truth of his own existence and in doing so has achieved the ultimate vindication, in denial he has achieved redemption.

The prevailing triumphant force in the story of Ciappelletto is innocence, a society so lovingly gullible as to be convinced of his purity is one corrupted by a set of ideals, yet unadulterated by another, “…the portrayal of a late-medieval Italian society in ideological and economic crisis, as found in the Decameron, becomes an allegory of late-capitalist society”. The future awaiting them was one that Boccaccio and the Decameron helped establish, the Italian aristocracy which collapsed into dictatorship and finally into capitalism. Innocence during this age persists and has such weight that art and sex prevail over almost every conflict, theological, financial or otherwise.

“The transactions of all the participants in this story, except for the priest-confessor, involve the lending or changing of money, the charging of interest: usury, a practice where money, obviously, is not identical to itself, literal denotative; if this were so then loans would supply no gains for lenders. This practice, furthermore, as Marx describes it in Capital, presupposes the abstraction of money from products of use values. That is usury entails a distancing of currency from the values it once was supposed to reflect.”

Pasolini chose to cherish the products of capital in an effort to distance the two from each other, not to reduce the importance of the products but to reduce the value of capital. Pasolini claimed he created the Trilogy of Life for the pleasure of telling stories, something he restated in interviews and most explicitly in the final moments of his adaptation of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Perhaps art and sex prevail over the forms of capital because in an Aristotelian sense they are pursued for the sake of themselves. Pasolini is creating something for the sake of itself in both craft and execution transcending capital through the joys of creation.

Sex is a primary focus of The Decameron, one of the earliest stories tracks a young man who leaves his job as a farmer to join a nunnery where he acts as though he is mute, the nuns take advantage of this to engage in the unknown glories of sexual interaction assuming he won’t be able to communicate to their fellow sisters. This would be a fantastic plan if all the nuns weren’t curious and he becomes a kind of living sex-toy for the entire nunnery. The boy breaks his silence to mother superior when he confesses he can no longer get hard because of all the nuns he has been having sex with. The mother superior then runs him into the church declaring God has given them a miracle, in order to work out their sexual situation with proper scheduling and planning, God has embellished the young man with the ability to speak. Innocence and creation once again prevail over the young man’s working conditions on a farm where no women were allowed, he was making money to garner food, increase his social standing, settle down, but he abandoned that to have sex with an entire nunnery, the irony of this inversion of the romantic longing for nature, farming, working with the seasons is eschewed in favor of a life of satisfying the sexual desires of a group of nuns. Through Pasolini’s eyes the latter is more pastoral, wholesome and innocent.

Pasolini casts himself in a brief role as “the artist” a disciple of Giotto, a famous chapel painter, who has traveled to a monastery to construct two murals. He is depicted as restless, taking his meals with the monks quickly and impatiently, eager to get back to his work. When the murals are completed in the films final scene, Pasolini as the artist, with the monks celebrating around him looks upon his work and utters the sentence “why complete a work when it is so beautiful just to dream it”. This line had far reaching implications for Pasolini’s life, proceeding catalog and most crucially to art’s relationship to capital, to the nature of having a “complete” work that for him as a filmmaker necessitates being sold, distributed and commodified the moment it’s finished. Art still possessed the potentiality to be incomplete in the medieval age, its rules and hegemonies had not yet been solidified, molded into cultural and social capital regulated to those who have time to interact with and control it.

Pasolini finished the Trilogy of Life in 1974, it cost him a personal relationship with his longtime lover Ninetto Davoli, who acted in all three films and featured roles in previous movies such as The Hawks and The Sparrows, in addition to his standing as an auteur taking a significant hit. The public reaction to the trilogy was largely receptive as a result of the frequent displays of sex and frivolity, however, the trilogy spawned a number of pornographic imitators, all updating ancient literature into steamy, exploitive depictions of sexual intercourse. Pasolini found innocence and grace in the these bodies, while others sought to intensify how gratuitous and explicit they stood to become. While working on the screenplay for Saló, Pasolini penned an abjuration to to the trilogy, confessing his feeling of loss, “I reject my Trilogy of Life, although I do not regret having made it”. The reception of his films disproves their sentiment: that bodies, sex, art are still pure, capable of immense innocence, but these nude bodies of the young proletariat boys and girls, Italian teenagers, were quickly reduced to pornography and vulgarity.

Sex as a form of exchange had become strictly capital, the act was no longer joyful but commodified, perverted, orchestrated to appeal strictly to base sensation, complete debasement. In the abjuration he calls out specifically the free-love movements of the late 60’s in America and more harshly the May of 68’ in France, feeling that the youths involved in these movements were privileged bourgeoise students who are only revolting out of a sense of entitlement and that they have failed to understand the full implications of their actions, “They do not see that sexual liberation, far from bringing ease and happiness to young people, has made them unhappy, shut off, and consequently, stupidly presumptuous and aggressive”.

Pasolini had succumbed to the helpless cynicism of the forms of capital, a world in which all human connection, projection and sharing is tainted by the material standard of the few. He felt that his trilogy was a failure, in the effort to destabilize the hegemonies of the bourgeoisie he became daunted, discouraged and pessimistic in reaction to the tight grip they have on the life of common people, he no longer saw antiquity with the same warm glow, instead felt the renaissance ushered in the establishment of the Italian aristocracy. The bodies of those paintings, chapels and monasteries had become frail and consumable, and perhaps always were.

“… I am adapting to the degradation and accepting the unacceptable. I maneuver to rearrange my life. I am beginning to forget how things were before. The loved faces of yesterday are beginning to turn yellow. Little by little and without any more alternatives, I am confronted by the present. I adjust my commitment to greater legibility (Saló).”

Saló, or the 120 Days of Sodom is ultimately the synthesis of Pasolini’s renewed cynicism. It was originally planned as part of another trilogy Pasolini’s Trilogy of Death, these films were intended to mirror the structure of the Trilogy of Life, adapting three tales from antiquity, distorting and spoiling their content. He was only allowed to complete Saló as he was murdered by fascists shortly before its release. These films would have explicitly agreed with Bourdieu’s theory but had implications about the state of our relationships that Bourdieu perhaps wasn’t conscious of.

Pasolini extends his method of contamination to its natural limits in Saló, this is an adaptation of the Divine Comedy, employing its form. The characters in the film travel through different circles, applying Dante’s journey into the underworld to a group of youths at the end of the fascist reign, who are enlisted to be sex slaves for the local leaders.

The first circle “Circle of Manias” involves the young boys and girls submitted to large orgies and pornographic stories read over gentle piano music while being groped by older men. Initially these older men submit the children to standard abuses of power, everything is horrific but nothing is yet surprising, the men are still obsessed and interested in the “normal” bounds of sex, they still have some semblance of the sexual morality and ethics imposed on them, the men begin to grow bored with this power; that rape, sex, cuckolding, are simply not enough. The standards of sex, even at their most simple are crafted by fascist powers, Pasolini then moves into his condemnation of what he calls “consumer fascism”.

The second circle “Circle of Shit” involves the fascist leaders growing increasingly disenfranchised with their power, so they long for more to compensate: they begin eating poop, forcing the children to defecate and eat their own waste. Pasolini used this as a metaphor to evoke the fast, cheap food of McDonalds, he felt the death of culture had already begun, right when we started eating our own shit. Further it exists for the pleasure of the few while debasing the masses, the men in all their excess enjoy covering their faces in shit and watching the children eat their excrement off the floor. All capital has been reduced to shit, whereas the forms of capital once retained integrity, pride, and strength, now they are little more than ugly tools serving the shallow sensibilities of the powerful few.

The final circle, “Circle of Blood” is the culmination of the madness of Saló, reducing the forms of capital to a single form: violence. Art, sex, food, beauty have all become vicious, cruel and self-serving. There is a moment of hope dispersed throughout this stomach-churning conclusion, a young girl is found to have a photo of family from home, she then tattles on two girls who have fallen in love, strictly forbidden to have sex with anyone but their masters, the two are threatened until they reveal that one of the young boys is sneaking out to the maids cabin at night and sleeping with her. When the leaders arrive to find the maid and young boy having sex they raise their guns to shoot them, both the young man and woman had starring roles in the Trilogy of Life, here they are slaves about to be murdered for the same acts they committed so carelessly in those films. The young proletariat in defiance forms his hand in a socialist symbol before pumping it into the sky. For just a second the fascists are frightened, the look on their faces recognizes the two most powerful forces in opposition to the forms of capital: love and hope. The film concludes with two young men in military uniform dancing in each other’s arms to the films theme as the sound of children being tortured ring from the courtyard behind them.

“The structures of the cinema therefore present themselves as transnational and transclassist rather than as international or interclassist. They prefigure a possible sociolinguistic situation of a world made tendentially unitary by complete industrialization and by the consequent leveling which implies the disappearance of particular and national traditions.”

Pasolini believed there was very little difference between cinematic reality and the one we experience in everydayness. He found his way towards the cinema as a result of feeling inadequate expression using the novel and poem. His “Cinema of Poetry” captures in its totality, films ability to transcend the forms of capital. Cinema survives but has succumbed to capital in a massive takeover by the corporate powers of industrialization to buy out cineplexes, movies are becoming spectacle rather than stories, blockbusters are becoming the new epic poem. Hegemonies have become so strong that the space for novel ideas, fresh ideologies and interesting solutions to old problems are waining, becoming increasingly stale, bland and repetitive. The forms of capital are brittle yet are more standardized than ever before, “The collapse of the present implies the collapse of the past”, what than of the future?

Further Reading

Bourdieu, Pierre “The Forms of Capital” The Sociology of Economic Life by Mark Granovetter, Routledge (2011). Pg. 46

Patrick, Rumble. Allegories of Contamination: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life, University of Toronto Press, 1996. Pgs. 102, 103, 112, 120, 133

Pasolini, Pier Paolo. “Trilogy of Life Rejected” Criterion Collection Spine #631. Pgs. 6, 7, 8

Insights- Fighting Back with Contamination: Pier and Pierre Our material world is defined and solidified by the movements of capital. In Pierre Bourdieu’s article “The Forms of Capital” he argues that capital crafts the “games of society”.

0 notes