#btw the white border means nothing it's just to make the writing more visible when needed

Text

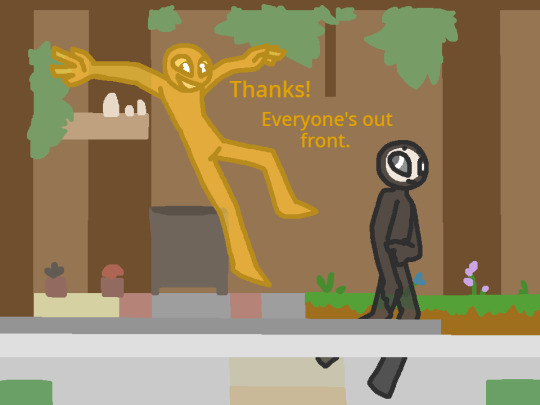

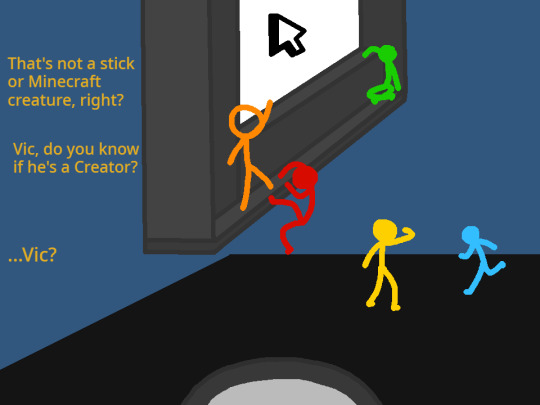

Cold Thoughts Ch 1

Welcome to my AvA comic Cold Thoughts! This should be around 14 chapters (give or take) coming out every Saturday.

For a little bit of context, this is not the first time Vic's met Alan after they died, but they tend to avoid him. Gold, however, is very excited to meet this new creature ^-^

Also this is directly connected to my prior au and headcanons so it follows all the rules of how ghosts work, including the void, ghosts affecting redstone, and most notably that only Vic can be visible (when they choose) on the computer.

First/Previous: You're here!

Next

#alan becker#animator vs animation#animation vs minecraft#cold thoughts#victim#gold#art#comic#color gang#they're technically here too#but i don't wanna list them all cause they're in one panel#blue's room was hard to draw#but i like how it turned out#btw the white border means nothing it's just to make the writing more visible when needed

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

The St Cyprian Scholar

An interview with José Leitão.

José Leitão is an author and scholar as well as a Portuguese Saint Cyprian devotee. Besides a PhD in experimental physics from the University of Delft, the Netherlands, his current research focuses on using ethnographic and folkloric methodologies to map the concepts of folk magic, sorcery, and witchcraft as described in the records of the Portuguese Inquisition.

The translator of "The Book of St Cyprian: The Sorcerer's Treasure", and the Bibliotheca Valenciana", both on Hadean Press as well as his collection of Portuguese folk tales related to the Cyprian Book "The Immaterial Book of St Cyprian" on Revelore Press and numerous articles he is developing a considerable body of Portuguese language works translated for the first time into English.

In my travels to Portugal for field research I cross paths with José in the university town of Coimbra, where he is currently conducting research. Over a handful of coffees I managed to get him to give me an interview about his work and research. He is almost as much of a recluse as I am!

+++

For a man with a background in physics you are making a considerable mark on the history of occult literature in the early 21st century. Is there some long term plan or are you more of the wandering academic/perpetual scholar type?

Let’s not start making history before it happens… you’re not the only skeptic around here. From what I’ve observed occult literature shifts its focus often and in unpredictable ways. I may yet be a one hit wonder.

That being said, I suppose it might be a bit of both, or perhaps neither… at least in regards to my written material. To be honest I had no plan behind my first book, it was something that just kind of happened due to a number of circumstances in my life and at the time I really didn’t think I would be writing anything else besides that.

It’s hard for me to describe this in detail at this point, because it’s difficult to tell what where my genuine feelings then or what are later rationalizations. The fact that I have a physics PhD is largely circumstantial, it barely has anything to do with anything I’m doing right now and I’ve turned my back on that world probably permanently. There’s likely no real point in going into details here, but after a very long time in that world I simply came to the realization that that life was not conducive to my happiness; a reflection which was very much aided by my work and translation of The Book of St. Cyprian. Once I figured that out I started doing everything I could to walk away from where I was, and that’s what I’m still doing. So, it’s not so much about being a wandering or perpetual academic, it’s really about the path of least emotional resistance and unpleasantness at this point.

But, of course, I could have chosen to go down the purely ‘practitioner’ way, but I chose academia instead. I’ve also come to realize that I can’t function properly outside of a university or a university-like environment, so I fully identify as an academic at this point, and indeed there is a lot of wandering involved in that.

When we talk about the myths and folklore of the people of the Iberian peninsula very little of the primary sources have made their way into English translation. Why now, what do you think is driving the growing interest in Iberian folk magic?

I think there are a number of issues at play simultaneously, and I don’t ascribe a necessarily ‘supernatural’ origin to any of them. It reads a lot like regular human geography and white people taking their heads out of their asses (btw, Iberians aren’t white; we simply think we are because we’ve always had somebody darker to compare ourselves to).

I read this as the reality that the major trendsetting countries (USA mostly) have had an increasing immigrant population from Portuguese and Spanish speaking countries for years now, but what makes this moment different is that the white people living there, due to contemporary political reasons, have started to pay them attention (and not always in the good way). This means that, right now, a lot of new concepts are being brought into cultural visibility which were exclusive to Iberian and South and Central America until very recent, not because they were hidden, but rather because no one gave a fuck.

You need to also remember that besides the long standing white disdain for anybody south of the American border, in Europe we still suffer the stigma of the Black Legend. The narratives of accepted modernity have always been historically presented, firstly, by Protestantism and, secondly, by the Enlightenment, both of which were (and are) ultimately profoundly hostile to Catholic Iberia, so the situation wasn’t (or isn’t) much better here. We have a European stigma associated with emigration and typical association with menial labor in central and north Europe. Iberians are still exotic and given to stereotyping as under educated simpletons (think Manuel from Fawlty Towers); a nice place to visit during the summer and be entertained by our quaint non-Europeaness.

So, a reappreciation of both these cultural spaces is happening right now, but I see this as happening mostly for mundane reasons. But also… regarding the Iberian aspect in itself in America… I’m going out on a limb here, so feel free to call bullshit on what follows, but I also think that there might still be some extra racism involved in this. ‘Iberian’ sounds old and ennobled; you get images ancientness, castles, knights errant, good food and wine and beautiful dancing gitana girls. For a white American, it removes the source of the practice from your immediate (brown) neighbors and places it in an old (assumed white) Iberian no one really knows anything about.

Lusitanian culture specifically is of particular interest to me personally. Remnants of pre Roman cultural ideas seem to be scattered within the larger dynamic of Portuguese culture. Do you think that forms of folk magic practice found in say the 2nd or 3rd century have continued down through the ages?

Interesting you mention the Lusitanian. One of the major (unintentional) overarching themes of my next book is actually Portuguese cultural identity, and I offer some criticism on the Lusitanian problem from a contemporary practitioner perspective.

This is really the sum of it: the identification of the Lusitanian as the par excellence pre-historical Portuguese (the Portuguese before there was Portugal) is a politically motivated construction of the Estado Novo for identity and cultural control. The Lusitanian continuity thesis was one of Vasconcelo’s babies, but this was far from being universally accepted and during its time it received very heavy criticisms, mainly from Alexandre Herculano, one of the greatest and most cursed Portuguese historians. However, due to this and other difficult issues regarding the, at times, overly romantic Portuguese historiographic tradition, Herculano was for a long time largely ignored, and Vasconcelos pretty much became the regime’s scholar of choice.

I’m not disparaging Vasconcelos, he was good at what he did, but scholars need to be given the right to be wrong. His work has, in the past, been used for sinister purposes and that shouldn’t be ignored anymore. You see, if you are a heavy paternalistic right wing clerical regime and you do a hard streamline to the Lusitanian, a people we still don’t really know that much about, as the ‘archaic’ Portuguese, you are able downplay every other major population influx into Portugal and fashion our ‘archaic’ identity in whatever way you see fit. This means that you get to downplay Neolithic dolmens and standing stones, Phoenician, Carthaginian, Greek, Roman, Jewish and Muslim/North African influences, and construct an idealized and racially pure Christian Portugal. The Lusitanian, as an identity, are essentially nothing.

But obviously I can’t say that there aren’t Lusitanian influences in what Portugal is or that this doesn’t exist in Portuguese folk magic. That would be another form of insanity, mainly because we simply don’t know what the Lusitanian did. But to isolate the Lusitanian like that is historically problematic. So… no, I don’t think 2nd or 3rd century practices are particularly visible, at least not more than Roman, Jewish or Muslim ones.

The idea of "Lusitanian" culture being used as a kind of nationalist symbol in which to rally people in support of a regime is fascinating. Years ago I studied kaballah with Lionel Ziprin in NYC and he had a whole theory about the "publicly accepted kaballah" that was presented by Gershom Scholem. How the texts that get translated and the things that are accepted as truths were part of a broader narrative meant to occlude certain aspects of historic kaballah. How involved do you think the church was in the utilization of this "Lusitanian" national identity?

That’s hard to say… one thing that also needs to be understood is that, even if the regime guided itself by Catholic morals and ideals, and the Church did draw immense social advantage from this, the Catholic hierarchy actually had very little power to influence the political decision making. Ultimately, by the accurate manipulation of words and an irreducible concordat, Salazar could instrumentalize the Church for political gain and identity and behavior control, and it ended up becoming as much a prisoner of the state as anybody else, leading to Catholic dissension in the 50s. So, probably the Church didn’t really have an active role in the utilization of the Lusitanian, it was simply another tool the regime could manipulate and fit together to selectively construct a useful identity and narrative of itself. Although I’m sure many within the religion didn’t really mind this.

In reading your "The Book of St. Cyprian: The Sorcerer's Treasure" on Hadean one concept that really interested me was this idea of the "mar Coalhado" or Curdled Sea. It struck me as both an afterlife in the model of the Norse Hel, but also some kind of purgatory or abyss. Though I have been unable to find much in English! Is this concept still common in Portuguese culture?

That’s also one of my favorite concepts, interestingly. This is something which is pretty much still in the air for me.

Ultimately, on a general or ‘global’ scale, I don’t think I can give you any actual answer to what this concept might be… or any such concept to be frank. If we’re going back in time to look for such ideas we must remember that we’re going into circumstances when the circulation of information had its limits. Most researchers tend to bypass this problem by implicitly assuming that such folk concepts are ‘ancient’ or ‘archaic’, which meant that they should have had time to spread homogeneously across large geographical areas. I tend to avoid this approach because it removes active agency and imagination from the non-contemporary, non-educated, or non-white individual practitioner. That being said, a few other scholars have noted the occurrence of mentions to the ‘Mar Coalhado’ or something of apparent equivalence in a few procedures. Most often nobody ever offers anything on it except its occurrence, but I recently ran across a particular book by a fellow Coimbra researcher called António Vitor Ribeiro, O Auto do Místicos, which seemed to shed some light on the matter. It’s a cool text, exploring ideas, descriptions and practices of mysticism in Portugal from the clerical and literary circles down to the folk and rural levels. It’s a very ambitious work, but he tend to do really clumsy simplifications and linearization via some sneaky moves using Ginzburg or Eliade, and he uses words of complex meaning and implicit significance very frivolously… I like my methodologies to be more hygienic. Anyway, in one of the many interesting Inquisition documents he finds there is a mentioning of something referred to as the ‘Aguas Salgadas’, or ‘Salty/Salted Waters’. It’s not a perfect fit, but it does seem like somewhat similar to what we’re discussing. But what’s more interesting is that this isn’t in an actual Inquisition processes and this wasn’t mentioned as part of a particular folk magic procedure.

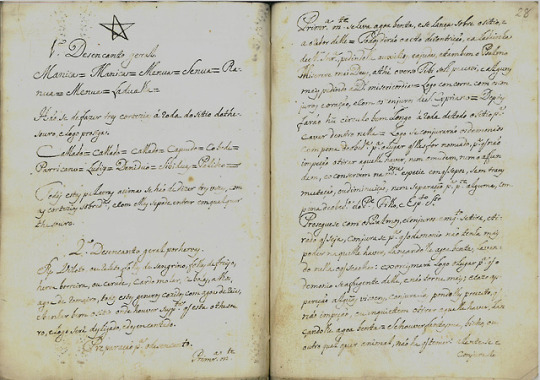

You see, there is a secondary collection of Inquisition documentation in Portugal called the ‘Cadernos do Promotor’, or the Prosecutor’s Notebooks, collections of denunciations, confessions or observations taken by Inquisition prosecutors that never made it into actual processes. There are several reasons for this, most often no crime was actually identified for a prosecution to be mounted, and other times it was because the reports and accusations are so outlandishly bizarre that the Inquisitors couldn’t make any theological sense of them in order to determine if what was being described actually constitutes heresy.

In this case, what was being reported were apparent visions, visitations and possessions by Mouras. Thus, a woman called Maria Leamara would fall into possession ‘rolling on the ground making it quake and making great arches with her feet’, saying while in this state ‘Let us go, let us go, let us go, let us go to the burrow of the moura, let us go, let us go, let us go, let us go across the salty waters, let us go, let us go, let us go, let us go to the Boulder of the See’. Then, when questioned about what any of this meant, she would only say that ‘they’ wanted her to deny Christ, and that the ‘salty waters’ meant outside of Christianity.

This whole thing then seems very akin to an anti-world, or ante-world, particularly evident by this apparent connection with Mouras, who apparently live across the Salty Waters and potentially the Curdled Sea. If Mouras are described and interpreted as these strange being of extremely remote existence, echoes and inhabitants of a bygone time, the banishing of something to this space would be akin to banishing it to somewhere outside of creation; this cosmic-now, or Christianity as that which created and defines the cosmic order we currently inhabit.

But in truth you have a number of varieties of this type of concept all across Europe. Very common formulas for the banishing of illnesses, bad weather or evil spirits into this type of space usually go along the lines of ‘go to where no baby cries, no roster sings or no dog barks’, for example, and I do see these as being somewhat equivalent concepts, as they both seem to describe a place removed from a humanly conceived cosmos, but these punctual examples of Moura crossovers do give it a particular local flavor.

If you think about it this is actually an extremely violent form of banishing. You’re basically casting something out of creation itself (as an anthropocentric concept). I think Jonathan Roper (one of my favorite folk magic scholars) has some material on this if you’d like to look him up.

But if you want to talk about actual application… even if some people might still use this concept (and it is quite common), I don’t think that what it actually signifies really is of much concern, even if it might be understood as significant. When you’re talking about magical formulas you always need to admit that there might be an aspect of simple habit or ‘tradition’ in the use of certain words and expressions. The impulse to break down an idea like that into tangible and rational concepts is pretty much a ‘learned’ and contemporary preoccupation. In all truth, a much more common occurrence in inquisition processes and documentation is that when an accused is questioned about a particular procedure he was witnessed as using, and which apparently calls upon a variety of spirits and characters, if asked who these characters are he will most likely answer that he simply don’t know. My reading of this is that it’s not their job or preoccupation to know; the words don’t have to have a rational meaning, which is something also supported by the observation that these types of traditional magical formulas frequently use nonsensical expressions, onomatopoeias or forced alliterations. The complete understanding of every single words and expression used beyond the cultural meaning of the procedure itself as a whole is a preoccupation which is mostly non-existent in the environment where these procedures occur. Both contemporary scholars and contemporary occultists are descendants from this overly analytical mentality, and it seems to me that the first step in actually understanding these is to admit that we are ultimately alien to this form of thinking.

You brought up the ‘Cadernos do Promotor’, or the Prosecutor’s Notebooks, which seem like a massive untapped resource in the folkloric study of witchcraft belief. Do you know if these types of records are only found in Portugal? How extensive are these documents?

To be honest, I’m still pretty new to that particular database and I’m not that familiar with the bureaucratic functioning of other Inquisitions in order to answer that question. However, in terms of how extensive… I’ve counted 352 volumes, some of which are 14 centimeters thick.

These are it. The thousands of processes everybody likes to talk and fetishisize about are just the tip of the iceberg; this is the real deal. Pure, uncut, unadulterated, untortured, uninterrogated words. No leading the witness, no feeding the answers to the accused, no theological projection, no nothing; just people voluntarily and spontaneously saying the crazy shit they saw, crazy shit they did and the crazy shit that was done to them.

The amount of work needed to work this source is soul crushing, but the potential is just breathtaking. Even beyond just the information in them… I’ve only scratched the surface on these, I’ve so far mostly been reading what other people have written about the reports in the Notebooks, but the things in there are dangerous on a cognitive level.

This goes back to the whole issue of the contemporary analytic mind, you need to remember that this is a window into a whole cosmology, worldview, understanding and interaction with the universe we simply don’t understand and are irreducibly alien to. Reading a few snippets has been enough for me to start to question reality… the ease and apparent normality which some things are described is just disturbing. And it gets Lovecraftian at the drop of a nickel… like ‘I was making a sandwich when all the sudden a door opened on the dark corner of my room. A Mouro with a red hat and shiny shoes walked out and lead me into a palace where the other Mouros were dancing and I met the Virgin Mary, who had the face of a monkey, her sister Saint Quiteria and King Sebastian and his five children. This has been happening every night and my husband complains that he wakes up when the Mouro takes me away during the night’… it’s stuff at this level and worst (or better).

With your recent complete translation of Jerónimo Cortez's "Bibliotheca Valenciana" you break into a realm of seeing and understanding the cosmological context in which much of the Cyprian magical traditions are rooted. A point before hard science, where the role of magician/scholar/alchemist merge and formed a kind of proto-scientist. What in Cortez's opus do you see as the most valuable content for those trying to understand the context of Cyprianic magic and early modern Iberian cultural beliefs in general?

Well… there’s a point in your question I can’t let slide. There is no such thing as a ‘proto-scientist’. The only way you can say that is if you root yourself in the contemporary time, take the definition of ‘scientist’ as it exists currently and project back in time to where it didn’t exist nor did it make sense (that’s the way most scientists think and why you can’t trust them to write their own history). So, the Cortez books don’t describe proto-science, they describe the science of their time, which is just as valid in its time as ours is in our time.

But regarding your question, there are a few points I wanted to make with the Bibliotheca Valenciana. The first of these is pretty straightforward: the Cortez books are not only one of the major sources for some of the later forms of the Cyprian Books, but they are themselves one of the major resources for your average Portuguese (and Brazilian) folk practitioner. While the reference to Cortez is actually fleeting in The Book of St. Cyprian I translated, as you move along the literary tradition of Cyprian Books, the repacking of material from the Physiognomy and the Lunario becomes ever increasing, particularly in Brazil. This by itself, in my own conception of what the work I’m supposed to be doing is meant to be, not only justifies the writing of that book but actually demands it.

The second point is probably more on the line of what you are alluding to. Besides the immediate relevance these books would have for someone interested in St. Cyprian related practices, they very efficiently describe what would be the early modern Catholic cosmology in purely functional terms and straight across social classes, even if this might at times not be completely explicit in the text. Note that there isn’t a distinction here between science and religion. Those are western academic categories and a person placing herself in the environment from where those books come from would not make this distinction in any way.

So, the point was not to simply offer context for St. Cyprian practices, but really to try to open up early-modern Catholicism as a still functional magical worldview and to offer the chance to approach the spiritual structures of the Church with an eye for (a rogue) practicality. If, as you say, Iberian folk magic is in fashion, if you try to reframe many of these practices into a Protestant cultural background (which is where Anglo-American occultism is based at), and if you’re serious about what you’re doing, you’ll run into more than a few bumps on the road. So the point was to offer a cosmology for when (or if) a cosmology is necessary.

And my final point with that book was part of a personal issue I’ve been working around regarding the nature of grimoires. I’m sure there are some purists out there who will vehemently disagree with me, and they might have a point; but I’ve come to think that that title cannot be solely given to a book by its author. If you analyze the way, historically, certain books are reacted to by the environments they enter you start to realize how arrogant it is to claim that one book is a grimoire in exclusion of another. ‘Grimoire’ should at times be a behavior description. It shouldn’t be about ‘this book is a grimoire’, but rather ‘I act towards this book as if a grimoire’. Once again, I believe that the denial of this is a ‘learned’ issue, a thing of high society and a claim of authoritarian elitism. So, to me, the Cortez books looked like Catholic grimoires in form and function, and they were certainly treated as such by people over here for hundreds of years, and logically they overlap with The Book of St. Cyprian. This is a line of work I intend to keep on exploring, and I’m actually right now planning on putting together something else further articulating this; some 18th century Catholic books I’ve recently fallen in love with.

When you talk about the Cortez books being used like grimoires, were his books perceived in Iberian society as "dangerous" or otherwise taboo in the way that Cyprian's Book was? Or do you mean more from a practical standpoint that the material in the book was used in much the same way one uses material in a grimoire?

I mean it from a practical standpoint mostly. This is something I’m still trying to figure out completely, but the construction of fear around the Book of St. Cyprian seems to be quite more recent than the Cortez books.

Overall I haven’t found that many references to Cyprian in the 17th-century, so it’s hard to say for certain what the image of The Book was for people familiar with it back then. But anyway, the emotional reactions to the two were probably very different. Although Cortez was a pioneer in the general prognostication literary genre, books of that sort weren’t particularly new or persecuted. They could at times be frowned upon (which lead to many being given false publication cities), and used as circumstantial evidence to prosecute someone accused of illicit practices, but they were never a particularly fearful thing in anyone’s eyes.

Witchcraft in Portugal is very under researched. It's my understanding that the history of witchcraft and its persecution is very different in Portugal than in neighboring Spain due to lack of an Inquisition in Portugal. What facets have shaped what we would call witchcraft practices that separate Portuguese and Spanish traditions?

First of all, a correction: Portugal did have an Inquisition. It started off slightly later than in many other countries, in 1536, but it lasted into 1821, so we had plenty of it over here. Now, what usually distinguishes it from many other such similar institutions was the absence of witch-hunting. While the practices perceived as witchcraft were still very much against the law, and if found these would be persecuted, there was no major active effort by any institution to actively search and persecute ‘witches’.

The only period where we do have anything close to a witch-hunt is actually in the 18th century, when you have a marked rise in related accusations. This instance had, for a long time, been somewhat of a mystery, but Timothy Walker in his Doctors, Folk Medicine and the Inquisition has very efficiently related this to an active effort by Coimbra trained doctors to eliminate folk healers and New Christian competitors from the market by becoming Inquisitional snitches. But overall, the number of witchcraft cases (and we can throw ‘superstition’, ‘magic’ and ‘sorcery’ in there) on the Portuguese side of things are actually quite reduced, seeing as the Inquisition was much more preoccupied with the persecution of hidden Jews (real or imaginary).

One other side of this is that the narratives of diabolical witchcraft popularized in other European countries didn’t find a very strong foothold here, leaving many of the descriptions of practices and ‘folk magical’ procedures free from learned projections, interpretations and prosecution. And finally, one other important particularity here was that witchcraft accusations didn’t seem to have a very pronounced female persecution aspect to them, with the divide being 40% male and 60% female… which really throws a wrenched into essentialist feminist witchcraft narratives.

What must be remembered is that witchcraft image construction is always culturally located, and to weave a Pan-European narrative is to fall into historical fallacies and anachronisms. Over here the typical targets of persecution were individuals who had no clear connection to any ‘public’ or ecclesiastic institution and had an uncertain source of income. In this category you then have widows, beggars, vagrants, Jews or day to day swindlers and small fry businessmen… and there are no significant Sabbat descriptions.

Comparing the case with Spain (of which I’m not an expert in by the way), it should also be noted that the usual portrait of the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition, in regards to witchcraft persecution, are inaccurate… that is another echo of the Black Legend. In Spain there were actually three parallel tribunals with authority to persecute witchcraft and related practices: the Secular, the Episcopalian and the Inquisitorial (mostly active in urban centers), and out of all of these the Inquisitorial was actually the most lenient. This has to do with the very Inquisitorial process, which tended to be extremely bureaucratic (leaving an immense paper trail which can be followed today, contrarily to the other tribunals which didn’t keep much of a record and consequently become less historically visible) and it was actually quite complex in terms of finding anyone guilty of such ‘immaterial’ crimes… again, against popular opinion and whatever savage nonsense was happening in Protestant Inquisitions. In order to condemn anybody to death for witchcraft, there needed to be proof of an explicit satanic pact, which was nearly impossible to achieve. Consequently, what we see with the Spanish Inquisition is that people accused of witchcraft or magical practices in rural areas would frequently flee to a city in order to be judged by an Inquisitional court because, even if they could end up condemned of something, the chance that they would be sentenced to death was much smaller. Maria Tausiet has a nice book on this actually, Urban Magic in Early Modern Spain, although she makes some horrible mistakes in her dealing with magic and folklore in general, going as far as quoting the Libro Magno de San Cipriano (from the 19th century) to explain spirit summoning in the early modern period…

The same thing is true of Portugal. Magic and witchcraft cases very rarely ended in death. It was much more common to give the accused a tap on the hand, give him or her a fine, have them make a public abjuration and them ship them off to one of the colonies or some forsaken place in the country. But you do start to find more common death sentences in relapse trials, but this once again wasn’t related to witchcraft itself, but rather because this implied that your original confession and abjuration had been a lie, which constituted sacrilege and was a considerably worst offense.

Ultimately, what in my opinion would distinguish both countries in terms of witchcraft narratives is something that goes beyond this straight duality of Portugal and Spain. True, we have had our borders nicely established for many hundreds of years and there are indeed certain distinctions that can be made between one side of the line and the other, but the error that this carries is that it is often assumed that whatever exists on either side of the border is itself homogeneous. There are some clear overarching motives and witchcraft narratives both in Portugal and Spain, but given the particular persecution circumstances, there are probably much stronger regional distinctions than national distinctions. There’s a very interesting book by Gunnar Knutsen, Servants of Satan and Masters of Demons, which very clearly demonstrate how ethnical and cultural differences between Northern and Southern Spain actually give rise to different forms of witchcraft narratives. I believe this should also be detectable in Portugal, and you could expect clear narrative distinctions between the North and the more Muslim influenced South.

Witchcraft image construction and narrative distinction is a very subtle field of work, and why I usually avoid talking about these issues with self described witchcraft practitioners. Contemporary witchcraft narratives tend to be monolithic and essentialist, and these are all pseudo-historical construction. I don’t mean this as an offense in any way; contemporary witchcraft has its own real history, and this is not in any way less ‘noble’ or worthy, but it’s most often not the history it tells of itself.

Contemporary feminist witchcraft, for example, while having a concrete and positive purpose in today’s society needs to be understood as being constructed over a particular narrative which is entirely local and politically motivated. The general tendency to want to apply this particular narrative, constructed by characters such as Margaret Murray and Gerald Gardener based on flawed and biased reading of historical documents, is a violent form of colonialism (curiously, a Patriarchic mode of behavior), frequently using anti-intellectualism claims in order to deny concrete historically observed practices and traditions that don’t fit a particular worldview.

Established religious traditions, be them Christian or Pagan, tend to have the same responses to what they perceive as attacks on their theological legitimacy and power monopoly. It’s the same mentality with a different opinion.

That was a bit of a tangent to your question I suppose… but as far as a distinction goes, that’s my position. I think a clear blind spot in Iberian Inquisition and witchcraft studies (and not just Iberian) is the common disregard for folklore and local culture to help frame and contextualize the several different practices being placed under the same category of ‘witchcraft’. This is once again a reflection of the ‘learned’ position of academic culture which is still a direct descendent of the actual Inquisitors who created this category in the first place (Wouter Hanegraaff has some nice material on this… although he doesn’t explicitly deal with the Inquisition and certainly not Southern Europe).

What projects do you have coming up?

I have a few things in the air right now. First and foremost, I spent most of last year traveling and researching for a new Cyprian book, and I’m hoping to have that published before the end of this year. This is one I’m very proud of and I think it’s safe to say that I found documentation that probably nobody had ever looked at (people have surely seen it, but not really looked).

It’s going to be something quite big I think, in the literal sense… it’s about 400k words long.

Other than this I have a few things on the drawing board. Like I already mentioned I’m playing around with a few 18th-century Catholic books from which I can make a very cool compilation of very pragmatically practical procedures involving Saints, exorcism and blessings. I think a thing like that would work very well with the Bibliotheca Valenciana, since the Bibliotheca is all about describing a Cosmology and this other one is all about practicality.

I have also a good list of papers and essays I’m working on, both as part of my current academic studies and my general writing. Most of these are based on particular selections of Inquisition processes of interest. There isn’t much of a study of magic and esotericism in Portugal, so this is the type of work that needs to be done in order to bring attention to understudied intellectual and religious currents over here. And, logically, in about four year I hope to have a thesis on folk magic and religion written.

José has organized a spectacular one day conference, "Colóquio Peculiar: Transdisciplinaridades improváveis", on occult and esoteric subjects to take place 8 June, 2018 at the University of Coimbra.

#skeptical occultist#st cyprian#occult#occult books#grimoires#hadean#cyprianos#bruja#bruxa#henban#witch#witchcraft#cunning craft#traditional witchcraft#poisoner's path#venefecium#maleficia#fae#sidhe#mouros#charm#hex#cursed#folkmagic#hedgewitch#alchemy#necromancy#conjuration#toadbone#ritual

215 notes

·

View notes