#at first hes awkward and throughout he continually does his part to create appropriate distance

Text

another note from the extended editions: what is the Aragorn/Eowyn dynamic? watching the theatrical cut it always seemed like a painfully unrequited crush. the extended edition scenes though... either I am crazy or or he DOES like her

#at first hes awkward and throughout he continually does his part to create appropriate distance#but he respects her and empathizes with her and thinks shes cute#lotr#grace for ts#obviously he's still living with the ghost of arwen in his thoughts 100% of the time#but likekkkkkke#its giving 'if this were another life and i were a different person' energy#when he pulled the blanket up over her after the feast?? am I nuts#I HAVE WISHED YOU JOY SINCE FIRST I SAW YOU im screaming#what a way to be told bye felicia

471 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert Renger-Patzsch: Aesthetics and Politics in times of Fascism

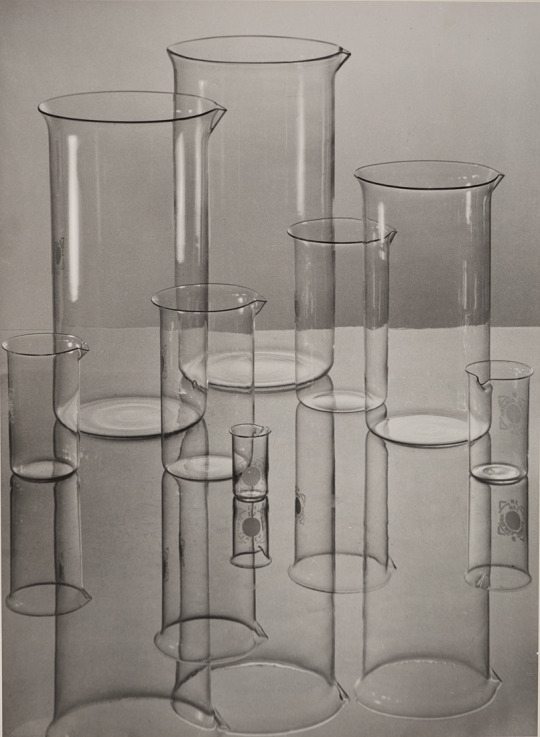

Albert Renger-Patzsch, Glass from Jena (cylindrical glass), silver gelatin print, 1934

When is it ignorant and dangerous to discuss art in purely aesthetic terms? The current retrospective of photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch at the Jeu de Paume in Paris (on view through the 21st of January) is a good example of what happens when art is inadequately contextualized by a museum.

Even though Renger-Patzsch claimed that his work was not art, but rather a truthful depiction of the things in our world - both man-made and natural - it is impossible to overlook how his precisionism and compositional rigidity made a lasting impression on generations of photographers and artists alike.

Albert Renger-Patzsch, Coal Mine “Graf Moltke”, silver gelatin print, 1952-53

The pictorial quality of his photographs is not in doubt: they are stunning, crisp, technically masterful. They show every minute detail of organic and manufactured surfaces. Clear lines and deep shadows emphasize the drama of light and dark, of form and structure. We never see imperfections in a glass, cracks in a wall of concrete, peeling paint or a flower’s torn petal. Renger-Patzsch serves us a vision of things that are part of an undisturbed, strangely airless world - as if all of it existed in a vacuum: the world as artifice. Aside from his earlier work on fishermen/-women and some artisans, people are extracted from all sites. This is not a world simply devoid of human activity and labor, but one that has been scrubbed down and sanitized with help of the photographic lens (and some off-camera arrangements).

Albert Renger-Patzsch, The “Iron Hand” in Essen, silver gelatin print, 1929

None of these characteristics are necessarily a critique of his work. Renger-Patzsch’s formalism is consequential and thorough, yet we have to ask: what were the limitations for artists in Germany of the late 1920s and early 1930s?

Starting in September 1933, just a few months after Hitler and his party had taken power, a cultural institution (the so-called ‘Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste’) was installed and tasked to oversee, shape and - where necessary - censor the visual arts. Scores of artists like Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix, George Grosz, John Heartfield were prohibited from working or chose to leave Germany altogether. In 1929 Renger-Patzsch’s contemporary and fellow photographer August Sander published the book Face of our Time which contained 60 portraits of people he had encountered across Germany. In 1936 the Nazis confiscated all remaining copies of the book and in addition, destroyed Sander’s negatives of his portraits as his project aimed at providing a cross-section of German society without maligning any particular group or individual.

August Sander, Soldier, Gelatin silver print, c.1940

Renger-Patzsch, on the other hand, continued to work through the 30s and early 40s, gaining lucrative commissions from coffee companies and pen producers to industrial heavyweights like Boehringer Ingelheim (to this day one of the leading pharmaceutical companies, the main supplier of morphine in Germany during WW2 and in the 1960s a supplier of Agent Orange for the US military).

Due to his interest in literature, Renger-Patzsch was in correspondence with leading German intellectuals like Hermann Hesse, Heinrich Böll and from 1943 to his death in 1966 with Ernst Jünger (In 1962 and again in 1966 the firm C.H. Boehringer Sohn - the sister company of Boehringer Ingelheim - commissioned Renger-Patzsch to produce photographs that were accompanied by Ernst Jünger texts.). If there is any confusion as to where Renger-Patzsch can be placed politically, his relation with the three writers does not actually help to shed any light. Hesse and Böll are affiliated with the liberal left and have been fierce critics of the Third Reich and Germany’s moral bankruptcy during Hitler’s reign throughout their careers. Jünger is an entirely different case. A highly decorated officer during WW1 and an early sympathizer of the National Socialists (Hitler’s party, who he thought had “more blood and fire than any of the recent revolutions”), Jünger remains a contested figure in Germany. He was able to maintain just enough distance to the unfolding horrors of the Third Reich while simultaneously engaging in intellectual flirtations with opposition figures and far left-politicians - a pattern (self-serving or not) that has rendered him politically ambiguous, if not entirely useless. In recent decades the so-called “New Right” movement in several Western European countries (similar to the Alt-Right in the US) has rediscovered him and reclaimed some of his ‘revolutionary conservatism’ as well as the idea of a ‘new nationalism’ to overcome the failures of the National Socialists.

In this light, it is awkward to enter the Jeu de Paume and visit the curator Sergio Mah’s exhibition where we find many quotes from Renger-Patzsche’s exchange with Ernst Jünger among the wall text, but no word on how these high forms of aesthetics mask the turmoil of the times they were created in. One could argue that the exhibition aptly titled “Things”, does not have to focus on the social or historical dimension of photography. But that would not be accurate either, since Renger-Patzsche’s work offers plenty of opportunities to discuss the ‘things’ we do not see or that we are not supposed to see right away.

Detail of “The Iron Hand in Essen” by Albert Renger-Patzsch, 1929

In the enlarged detail above, Renger-Patzsch captured some political graffiti that was written on the factory wall of the “Iron Hand”. The German reads as follows: “Die Arbeiter müssen wählen & siegen.” The workers must vote & win. Above the “&” (that looks more like a 9), somebody has added a swastika. After the great crash in 1929, Germany held a referendum later that year in December which resulted in significant gains for Hitler’s National Socialists. It is similarly significant that Renger-Patzsch recorded a political slogan which stands out among 190 photographs of plants, trees, rocks, factories and landscapes. We do not gain any more insight into this photographer’s beliefs or political identity and it might not even matter for his work. But what matters is that even a formal purist and admirer of the surface like Renger-Patzsch could not entirely escape the pull of his time. To suddenly see written language (the graffiti in this case) alongside his well-tuned and polished pictorial language, seems entirely appropriate given the context of Germany in 1929. And it is not just appropriate but enlightening to see that the complicated realities that brought down the Weimar Republic, while giving rise to the Third Reich, coexist side by side with the artistic, formalist features in this image. This photograph demonstrates how a mix of willful blindness (the kind of blindness that comes with wide-open eyes), excitement about progress and human-made environments, paired with the promise of a better future for the workers and capitalists alike, lead to a quick disenchantment with only two options: resistance or survival. It is safe to assume that Renger-Patzsch chose the latter.

Albert Renger-Patzsch, Ruins in the Segeroth neighborhood of Essen, Gelatin silver print, 1943

A year before Renger-Patzsch lost many of his archived negatives to an allied bombing and the ensuing fire, he documented the first air raid on the city of Essen where he had been living since 1929. What is remarkable about these ruin photographs is how Renger-Patzsch tried to uphold a sense of order and strict composition while the conditions on the ground did not allow for such impositions. The tall tower in the middle of the background and the lone figure right in the center of the image offer the only reference to his trade-mark composition - the rest lies in ruins and beyond his control.

The exhibition “Things” at the Jeu de Paume has missed an opportunity to follow through with Renger-Patzsch’s approach to the world: to examine it closely, to linger on the surfaces of things and to assume a reality beyond those surfaces. There is no need to accuse Renger-Patzsch of a lack of social awareness or political urgency. What he does, he does extremely well and he owns his place within the history of photography. But museums and curators (and galleries by extension) have a responsibility to direct their viewers toward those things unseen, the things that lie beyond the physical works of art and are generally considered part of history - political, social, intellectual or otherwise. There is a lot of pleasure in admiring beautiful art objects, but there is so much more to learn if we ask ourselves how they were made, under what conditions, when and why. And thankfully, it is never too late to learn.

#albert renger-patzsch#renger-patzsch#photography#formalism#minimalism#war photography#jeu de paume#things#august sander#third reich#national socialist#hitler#ernst jünger

2 notes

·

View notes