#and nobody is ever fully immune to the effects of social media

Text

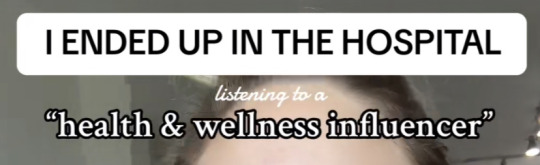

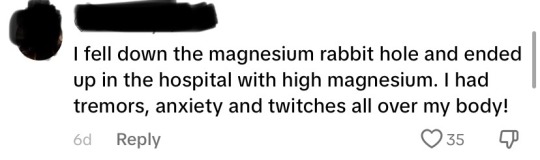

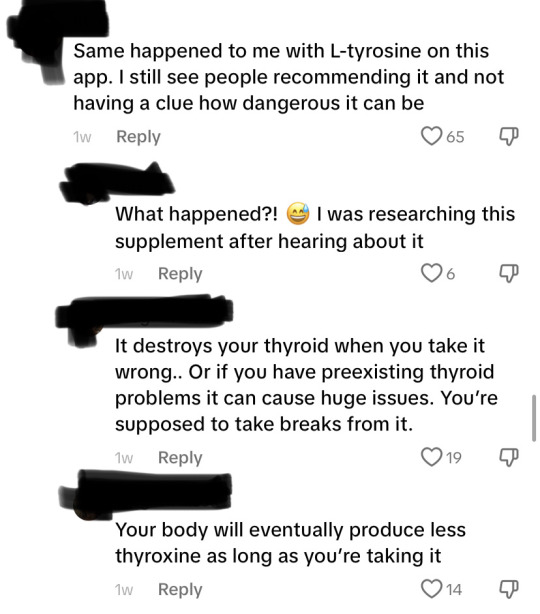

this poor woman ended up in hospital because she ate cayenne + cinnamon coated orange (unpeeled) because there’s a health and wellness influencer with millions of views who recommends it for digestion - she burned her oesophagus

i always saw a few really good other additions of similar things on the comments

please be so, so careful taking advice from these people online, as many of them are not formally trained or educated, brand ambassadors, deep in pseudoscientific rabbit holes and unfortunately, there are many out there who struggle with disordered eating habits

(not mentioned here but another one worth noting: i have personally known people who have burned their oesophagus with viral apple cider vinegar shots and drinks. don’t do that. a burned oesophagus is not fun)

#also tbh I’ve had this before this previous posts: please don’t make fun of people who fall victim to these kinds of things#lots of them have chronic health conditions and feel unlistened to and are desperate for remedies for their conditions#and nobody is ever fully immune to the effects of social media#katie rambles#ask 2 tag#wellness culture#<- tag for this kinda shit

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐅𝐑𝐔𝐈𝐓𝐘 𝐇𝐄𝐀𝐃𝐂𝐀𝐍𝐎𝐍 𝐏𝐑𝐎𝐌𝐏𝐓𝐒 ♡ 𝐒𝐘𝐌𝐁𝐎𝐋 𝐌𝐄𝐌𝐄

Instead of having people send these in I just wanted to do all of them myself!

🍍 : how comfortable is my muse in their body? how do they feel about their height, weight, strength, and body type? how important is being attractive to them?

All Scanners share virtually the same physical form, and all YoRHa units use the same base endoskeleton, though the hardware differs between function. They’re short and small-framed to save the maximum amount of materials while still being able to effectively perform their duties. 9S has never felt self-conscious about himself physically because he looks almost identical to every other Scanner and there was never any pressure on any of them to look a certain way like there is with humans. They have no ability to change their height or weight (though non-YoRHa androids can do so for aesthetic purposes if they choose) and it’s forbidden by their uniform code to modify their bodies anyway.

Since coming to Koi, 9S is quite aware now that he would be very short for a human of his apparent age, but he doesn’t feel bad about it or anything, other than occasionally being irritated at getting mistaken for a kid.

🍅 : how does my muse feel about plastic / cosmetic surgeries & procedures? is it something they have done or would do? do they mind if others do it?

As mentioned before, it’s forbidden for YoRHa units to try and alter their bodies, even if it’s for something like a tattoo or piercing. 9S doesn’t feel like he has any reason to do so right now, but that might change in the future. He doesn’t care if others do it. It’s their choice to do what they want with their bodies, as long as they understand the consequences.

🍏 : how stable is my muse’s physical health? do they go for regular or semi-regular checkups by a physician? do they have any diagnosed illnesses and / or take any medication? how often do they get sick?

9S knows maintenance is extremely important, and he is fairly accident-prone it seems. He’s had a limb or two blown off by machines more than once. Although he’s not a Healer unit, he’s gotten used to performing repairs on himself in the field and gets fussy if he has to sit around and wait while someone else fixes him up or checks him for viruses. As an android, he’s immune to biological pathogens, so there’s never any reason to worry about that. Currently he is functioning just fine.

🍎 : how stable is my muse’s mental health? have they been diagnosed with any mental illnesses and / or conditions? do they have any undiagnosed mental illnesses and / or conditions? do they or should they attend therapy?

An android’s mind doesn’t work the same way as a human’s, but it’s still very possible for their data to get scrambled or glitched due to trauma. 9S was supposedly wiped clean after every execution, but that doesn’t mean nothing ever remained, and every time he rediscovered the true reason for his partnership with 2B it became more and more painful to confront.

9S does an excellent job at convincing himself he’s stable, but it’s quite easy to push him over the brink. His emotions are terribly repressed so one needs only to scratch the surface to draw them out. He really should talk to somebody about this but there are no therapists on the Bunker.

🍑 : how meticulously does my muse look after their physical appearance? do they spend a lot of time on their hair, makeup, grooming, and clothing? is there a particular reason why they do or don’t?

9S really likes to be clean! Although it’s not necessary for androids to bathe, since their bodies are naturally resistant to dirt and moisture and they don’t sweat, he doesn’t enjoy getting all dusty or covered in machine oil and will wash himself off the first chance he gets. He finds being dirty very distracting. Keeping one’s dermal layer repaired is a vial part of maintenance as well, so he mends any small cuts or scuffs quickly.

🍒 : how much does my muse value companionship? do they constantly keep people around them, or do they prefer to be alone often? do they have or desire to have many friends? do they see every meeting as an opportunity to make a new friend?

Although Scanners are often solitary, 9S really enjoys being around others and will eagerly socialize with other androids. If only the resistance members wouldn’t stop trying to get him to run errands for them... He’s friendly with the other Scanners and will spend time with them if they’re on the Bunker together, though they seem to hold him at arms’ length for reasons he understands now.

2B is a special case, being his bodyguard of sorts. She could even be considered his best friend, and though his feelings of fondness for her are genuine, they’re very complicated. He’s happy she’s here. He’s also thrilled to be making so many new friends on the islands and does his best to make a good first impression, especially with humans.

🍇 : how would my muse describe their childhood? how much has it impacted the person they are now, or will become as an adult? around what age did they or will they start to mature, and why? do they wish to go back to their days as a child, or have they embraced adulthood?

9S was ‘born’ fully-functional and did not have a childhood of any sort. He didn’t even get to shadow a senior Scanner or anything, he was thrown right to the wolves. Such as it is.

🍐 : how intelligent is my muse overall? are they smarter than the average person, or less than? are they primarily self-taught, or did they acquire most of their knowledge in school? are they more street smart or book smart?

Uncommonly clever and observant, even among his own kind, though prone to making reckless decisions when driven by his emotions or his insatiable desire for answers. 9S has access to vast informational databases he can draw from, even in his own archives, with even more stored on his Pod he could summon at any time... if his Pod was here.

🍉 : which of the four seasons suits my muse best, and why?

Winter. Everything is buried, dormant, appearing quiet and serene on the surface.

🍌 : is my muse inclined to help others, or will they only do it when it benefits them, if at all? what makes them this way? has it ever gotten them into trouble, or inconvenienced them?

9S doesn’t mind helping others, though he can get irritated if given tasks he feels will distract from his mission, or that are boring or too difficult. When it comes to helping the surface androids, they more often than not involve combat with machines and him and 2B risking their lives, which he finds completely annoying, and not fun, but he still does it anyway.

🍊 : does my muse desire romance? is it something they would actively seek out, or prefer to happen more ‘ naturally? ’ what is their love life like? do they have any exes or past flings, or crushes?

Relationships between YoRHa units are officially banned, though the rule is not enforced very strictly. 9S has a hard time comprehending the complexity of romance and prefers not to think about it, perhaps unconsciously convinced he doesn’t deserve to have anybody feel that way about him.

🍓 : how is my muse typically seen by others? does it ring true to who they really are? does their reputation matter to them?

I would imagine, based on his youthful appearance and friendly, earnest demeanor, a lot of people would assume he’s a lot more naive than he really is. 9S lacks a lot of knowledge about how modern society functions, but that’s because he arrived 6,000 years too late to the party. He picks up on things extremely quickly and is quite socially perceptive. Fitting in is important to him, having come from such a conformist culture as YoRHa.

🥝 : does my muse have any ‘ unusual ’ habits, interests, and / or talents? do they hide it, or are they proud of it?

9S is more interested in human culture than most Scanners and especially enjoys collecting human-created media, particularly music, which he stores on his Pod and plays when he’s out scouting. He’s had a great time in Koi renting movies from the library, because entertainment options back home were extremely limited. He’s also gotten into fishing because of 2B.

🍋 : what kind of diet does my muse have? do they eat regularly, or the standard 2-3 meals a day? do they have to be reminded to eat, or are they likely to remind others? do they cook, or have others cook for them? do they eat healthily, or not so much?

As an android, 9S doesn’t require food to live. He can’t feel hunger or satiation. YoRHa units are powered entirely by the reactors in their black boxes, which only require water to function. Most of the time they can get all the fuel they need from vapor in the air they breathe, though in dry climates they’d need to find a water source.

However, eating is an important communal activity, so they have a limited ability to do so. They don’t have stomachs or digestive systems. Any matter they consume is incinerated as soon as it’s swallowed. As a Scanner, 9S can analyze the chemical makeup of things he tastes, so he’s always putting weird shit in his mouth just to see what it’s made of. He enjoys eating with others, especially after difficult missions. It’s relaxing, even if the food is usually terrible because nobody has proper ingredients.

🥭 : how important to my muse is their hometown, or where they’re from? are they proud of it, or considered a hometown hero? did they move away, or do they wish to?

9S doesn’t have a hometown, unless the orbital base he was manufactured on counts. He doesn’t like spending extended amounts of time there, because there’s not much to do, but returning is often required in order to meet with the commander and receive mission details. It’s kinda nice to be able to look down at Earth from space, though...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

YANGON, Myanmar ― Su Myant Sandar was 17 when she first noticed a red patch on her cheek. At the time, she was working with her girlfriends at a garment factory on the poor outskirts of this city. She covered the spot with a thick layer of thanaka, a traditional plant-based makeup, and continued going to work as normal.

But it was not an ordinary spot. It was the first visible sign of leprosy, a largely forgotten bacterial infection that affects tens of thousands of people every year, mostly in southeast Asia and most of them extremely poor. An ancient disease, leprosy causes skin lesions and nerve damage and can lead to severe disfigurement and disability.

Though curable and not highly contagious, the disease has long carried an intense social stigma, one that used to relegate people with leprosy to the fringes of Myanmar society. Modern treatment has erased some of this stigma, but even those who are cured shoulder a heavy emotional burden.

By the time the lesions spread across her body, Su Myant Sandar was out of a job and isolated from her friends. Already an orphan, she ate by herself every day, with her own fork and glass. Her brother quarreled constantly with his wife about her staying with them. She’d started receiving treatment at a local hospital, but it made her so lonely and exhausted that she stopped going before she was fully healed.

Su Myant Sandar’s relapse, months later, was severe. The disease reappeared in new patches on her skin, while weakness and numbness crept into her hands. She caught tuberculosis around the same time.

Her family decided to send her to the Myitta leprosy asylum, two hours away from Yangon. She’s still there today.

Now 20 years old, Su Myant Sandar is on the 11th month of a yearlong treatment at Myitta. She will be completely cured soon, but her limbs are covered with deep scars and have grown as thin as a child’s. Still, she says she feels “very lucky.” Unlike many other patients at the center, some of whom are in wheelchairs, leprosy didn’t mar her face or paralyze her fingers permanently.

Contrary to popular belief, the disease doesn’t cause body parts to fall off. But in extreme cases, it damages nerves so much that patients won’t feel injuries and might not treat wounds properly, which in turn can lead to infection and amputation. Facial paralysis and blindness may occur, and fingers and toes may curl and shorten. The disease can also destroy nasal cartilage, causing the nose to collapse entirely.

Even though Su Myant Sandar escaped some of leprosy’s most devastating physical complications, she has no dream of a boyfriend or a family in her future.

“A normal man would not want me,” she said in a resigned monotone.

“I don’t want to leave this place ever again,” she added. “I don’t want to go back home ever again. I have an ‘auntie,’ a ‘sister’ and friends here. They are like me. They don’t reject me.”

Su Myant Sandar has plenty in common with the other 130 patients at the Myitta center. They share a background of poverty, malnourishment and fear of an “outside” world that has inflicted on them the deep wounds of abandonment and rejection.

Centers such as Myitta give shelter and food to people who are often unable to provide for themselves due to disability. In the past, people with leprosy often lived around hospitals, either producing alcoholic drinks or begging, or ended up in rundown colonies where people died of malaria in great numbers. But in the bright, Spartan wards of this modern structure, patients can receive visits and move in wheelchairs around the tranquil courtyard.

Scientists believe leprosy is spread when a person carrying the bacteria coughs or sneezes and a healthy person inhales the droplets. Transmission requires prolonged, close exposure, but the odds of contagion are higher among people with compromised immune systems or who live in houses with no ventilation.

“The majority of the population ― even doctors and nurses exposed to leprosy patients ― would not get it,” said Dr. Zaw Moe Aung, country director of the Leprosy Mission Myanmar, which provides medical assistance to centers such as the Myitta facility.

Malnourishment and poverty affect vast segments of Myanmar’s population of 51 million. Newly recorded leprosy cases average about 3,000 per year here.

“Fifteen percent of the new cases are still identified too late, when preventable symptoms such as loss of sensitivity or claw hands mean nerve functions are compromised,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

In the 1980s, a multidrug therapy arrived on the scene. It proved effective in fighting leprosy around the world and is still the main form of treatment. If patients get this treatment at a point in the disease where their nerves are still repairable, they can avoid permanent disability. But many are cured only after the disease has rendered them unable to walk, write or see.

This treatment, which the World Health Organization began offering for free in 1995, worked wonders in Myanmar ― for a while, anyway. Thanks in part to a global effort, spearheaded by the WHO, to stamp out leprosy, Myanmar was able to significantly reduce the prevalence of the disease. In 2000, the WHO declared that leprosy had been eliminated as a health threat across much of the world. Myanmar, only slightly behind the curve, achieved elimination in 2003.

But “elimination” does not mean a disease is gone completely ― only that it’s been reduced to a manageable level. Even after things reached that point in Myanmar, there was still much work to be done. And unfortunately, worldwide efforts to fight leprosy have stalled.

As in the rest of Southeast Asia, where 74 percent of the world’s leprosy cases occur, the number of new cases in Myanmar is declining very slowly.

“Announcing that it had been ‘eliminated’ sent the wrong signal to the world,” Zaw Moe Aung said. “Donors halted funding and even health workers lost interest ― there was no inspiration for new generations to go and work with leprosy patients.”

“They would flock to HIV, TB, and get doctorates studying these illnesses, while nobody cared about leprosy,” he went on. “But you still need treatment, support for disabled patients and prevention education for the wider community. It might otherwise spread or be detected when it’s too late.”

In Myanmar, public information campaigns featuring writers and celebrities also helped to bring down the number of new cases, and to reduce the stigma that once saw people forcing patients off buses, burning their homes and sending them to live in separate villages ― even after their illness had been treated. But the judgment is still there.

“Self-stigma is also a real problem,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

U Aye Ko, an 80-year-old former magician and a patient at Myitta, says he felt like he needed to cut himself off from the world.

“I did not want my family to become a disgrace,” he said.

U Aye Ko used to perform in theaters all over the country. When he was 50, a red patch that had been on his hip for years started spreading. Leprosy symptoms can take up to 20 years to develop, so when new lesions appeared and his hands eventually lost sensitivity, he decided to leave his home.

“I felt inferior. I preferred to go,” he said. But even though leprosy has deformed his hands, he added, he can still perform the tricks his grandfather taught him, like conjuring flowers from his mouth.

His days of public performances may be over, but his desire to reunite with his family has grown stronger.

“I will try to make contact with them,” U Aye Ko said. “I know that my nephews live in Singapore. I would like to know how they are.”

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to [email protected]. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

When Bullets Fly, These Medics Grab Their Packs And Treat Patients On The Run

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017 published first on http://ift.tt/2lnpciY

0 notes

Text

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

YANGON, Myanmar ― Su Myant Sandar was 17 when she first noticed a red patch on her cheek. At the time, she was working with her girlfriends at a garment factory on the poor outskirts of this city. She covered the spot with a thick layer of thanaka, a traditional plant-based makeup, and continued going to work as normal.

But it was not an ordinary spot. It was the first visible sign of leprosy, a largely forgotten bacterial infection that affects tens of thousands of people every year, mostly in southeast Asia and most of them extremely poor. An ancient disease, leprosy causes skin lesions and nerve damage and can lead to severe disfigurement and disability.

Though curable and not highly contagious, the disease has long carried an intense social stigma, one that used to relegate people with leprosy to the fringes of Myanmar society. Modern treatment has erased some of this stigma, but even those who are cured shoulder a heavy emotional burden.

By the time the lesions spread across her body, Su Myant Sandar was out of a job and isolated from her friends. Already an orphan, she ate by herself every day, with her own fork and glass. Her brother quarreled constantly with his wife about her staying with them. She’d started receiving treatment at a local hospital, but it made her so lonely and exhausted that she stopped going before she was fully healed.

Su Myant Sandar’s relapse, months later, was severe. The disease reappeared in new patches on her skin, while weakness and numbness crept into her hands. She caught tuberculosis around the same time.

Her family decided to send her to the Myitta leprosy asylum, two hours away from Yangon. She’s still there today.

Now 20 years old, Su Myant Sandar is on the 11th month of a yearlong treatment at Myitta. She will be completely cured soon, but her limbs are covered with deep scars and have grown as thin as a child’s. Still, she says she feels “very lucky.” Unlike many other patients at the center, some of whom are in wheelchairs, leprosy didn’t mar her face or paralyze her fingers permanently.

Contrary to popular belief, the disease doesn’t cause body parts to fall off. But in extreme cases, it damages nerves so much that patients won’t feel injuries and might not treat wounds properly, which in turn can lead to infection and amputation. Facial paralysis and blindness may occur, and fingers and toes may curl and shorten. The disease can also destroy nasal cartilage, causing the nose to collapse entirely.

Even though Su Myant Sandar escaped some of leprosy’s most devastating physical complications, she has no dream of a boyfriend or a family in her future.

“A normal man would not want me,” she said in a resigned monotone.

“I don’t want to leave this place ever again,” she added. “I don’t want to go back home ever again. I have an ‘auntie,’ a ‘sister’ and friends here. They are like me. They don’t reject me.”

Su Myant Sandar has plenty in common with the other 130 patients at the Myitta center. They share a background of poverty, malnourishment and fear of an “outside” world that has inflicted on them the deep wounds of abandonment and rejection.

Centers such as Myitta give shelter and food to people who are often unable to provide for themselves due to disability. In the past, people with leprosy often lived around hospitals, either producing alcoholic drinks or begging, or ended up in rundown colonies where people died of malaria in great numbers. But in the bright, Spartan wards of this modern structure, patients can receive visits and move in wheelchairs around the tranquil courtyard.

Scientists believe leprosy is spread when a person carrying the bacteria coughs or sneezes and a healthy person inhales the droplets. Transmission requires prolonged, close exposure, but the odds of contagion are higher among people with compromised immune systems or who live in houses with no ventilation.

“The majority of the population ― even doctors and nurses exposed to leprosy patients ― would not get it,” said Dr. Zaw Moe Aung, country director of the Leprosy Mission Myanmar, which provides medical assistance to centers such as the Myitta facility.

Malnourishment and poverty affect vast segments of Myanmar’s population of 51 million. Newly recorded leprosy cases average about 3,000 per year here.

“Fifteen percent of the new cases are still identified too late, when preventable symptoms such as loss of sensitivity or claw hands mean nerve functions are compromised,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

In the 1980s, a multidrug therapy arrived on the scene. It proved effective in fighting leprosy around the world and is still the main form of treatment. If patients get this treatment at a point in the disease where their nerves are still repairable, they can avoid permanent disability. But many are cured only after the disease has rendered them unable to walk, write or see.

This treatment, which the World Health Organization began offering for free in 1995, worked wonders in Myanmar ― for a while, anyway. Thanks in part to a global effort, spearheaded by the WHO, to stamp out leprosy, Myanmar was able to significantly reduce the prevalence of the disease. In 2000, the WHO declared that leprosy had been eliminated as a health threat across much of the world. Myanmar, only slightly behind the curve, achieved elimination in 2003.

But “elimination” does not mean a disease is gone completely ― only that it’s been reduced to a manageable level. Even after things reached that point in Myanmar, there was still much work to be done. And unfortunately, worldwide efforts to fight leprosy have stalled.

As in the rest of Southeast Asia, where 74 percent of the world’s leprosy cases occur, the number of new cases in Myanmar is declining very slowly.

“Announcing that it had been ‘eliminated’ sent the wrong signal to the world,” Zaw Moe Aung said. “Donors halted funding and even health workers lost interest ― there was no inspiration for new generations to go and work with leprosy patients.”

“They would flock to HIV, TB, and get doctorates studying these illnesses, while nobody cared about leprosy,” he went on. “But you still need treatment, support for disabled patients and prevention education for the wider community. It might otherwise spread or be detected when it’s too late.”

In Myanmar, public information campaigns featuring writers and celebrities also helped to bring down the number of new cases, and to reduce the stigma that once saw people forcing patients off buses, burning their homes and sending them to live in separate villages ― even after their illness had been treated. But the judgment is still there.

“Self-stigma is also a real problem,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

U Aye Ko, an 80-year-old former magician and a patient at Myitta, says he felt like he needed to cut himself off from the world.

“I did not want my family to become a disgrace,” he said.

U Aye Ko used to perform in theaters all over the country. When he was 50, a red patch that had been on his hip for years started spreading. Leprosy symptoms can take up to 20 years to develop, so when new lesions appeared and his hands eventually lost sensitivity, he decided to leave his home.

“I felt inferior. I preferred to go,” he said. But even though leprosy has deformed his hands, he added, he can still perform the tricks his grandfather taught him, like conjuring flowers from his mouth.

His days of public performances may be over, but his desire to reunite with his family has grown stronger.

“I will try to make contact with them,” U Aye Ko said. “I know that my nephews live in Singapore. I would like to know how they are.”

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to [email protected]. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

When Bullets Fly, These Medics Grab Their Packs And Treat Patients On The Run

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

from http://ift.tt/2q1wwHb

from Blogger http://ift.tt/2pgEefJ

0 notes

Text

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

YANGON, Myanmar ― Su Myant Sandar was 17 when she first noticed a red patch on her cheek. At the time, she was working with her girlfriends at a garment factory on the poor outskirts of this city. She covered the spot with a thick layer of thanaka, a traditional plant-based makeup, and continued going to work as normal.

But it was not an ordinary spot. It was the first visible sign of leprosy, a largely forgotten bacterial infection that affects tens of thousands of people every year, mostly in southeast Asia and most of them extremely poor. An ancient disease, leprosy causes skin lesions and nerve damage and can lead to severe disfigurement and disability.

Though curable and not highly contagious, the disease has long carried an intense social stigma, one that used to relegate people with leprosy to the fringes of Myanmar society. Modern treatment has erased some of this stigma, but even those who are cured shoulder a heavy emotional burden.

By the time the lesions spread across her body, Su Myant Sandar was out of a job and isolated from her friends. Already an orphan, she ate by herself every day, with her own fork and glass. Her brother quarreled constantly with his wife about her staying with them. She’d started receiving treatment at a local hospital, but it made her so lonely and exhausted that she stopped going before she was fully healed.

Su Myant Sandar’s relapse, months later, was severe. The disease reappeared in new patches on her skin, while weakness and numbness crept into her hands. She caught tuberculosis around the same time.

Her family decided to send her to the Myitta leprosy asylum, two hours away from Yangon. She’s still there today.

Now 20 years old, Su Myant Sandar is on the 11th month of a yearlong treatment at Myitta. She will be completely cured soon, but her limbs are covered with deep scars and have grown as thin as a child’s. Still, she says she feels “very lucky.” Unlike many other patients at the center, some of whom are in wheelchairs, leprosy didn’t mar her face or paralyze her fingers permanently.

Contrary to popular belief, the disease doesn’t cause body parts to fall off. But in extreme cases, it damages nerves so much that patients won’t feel injuries and might not treat wounds properly, which in turn can lead to infection and amputation. Facial paralysis and blindness may occur, and fingers and toes may curl and shorten. The disease can also destroy nasal cartilage, causing the nose to collapse entirely.

Even though Su Myant Sandar escaped some of leprosy’s most devastating physical complications, she has no dream of a boyfriend or a family in her future.

“A normal man would not want me,” she said in a resigned monotone.

“I don’t want to leave this place ever again,” she added. “I don’t want to go back home ever again. I have an ‘auntie,’ a ‘sister’ and friends here. They are like me. They don’t reject me.”

Su Myant Sandar has plenty in common with the other 130 patients at the Myitta center. They share a background of poverty, malnourishment and fear of an “outside” world that has inflicted on them the deep wounds of abandonment and rejection.

Centers such as Myitta give shelter and food to people who are often unable to provide for themselves due to disability. In the past, people with leprosy often lived around hospitals, either producing alcoholic drinks or begging, or ended up in rundown colonies where people died of malaria in great numbers. But in the bright, Spartan wards of this modern structure, patients can receive visits and move in wheelchairs around the tranquil courtyard.

Scientists believe leprosy is spread when a person carrying the bacteria coughs or sneezes and a healthy person inhales the droplets. Transmission requires prolonged, close exposure, but the odds of contagion are higher among people with compromised immune systems or who live in houses with no ventilation.

“The majority of the population ― even doctors and nurses exposed to leprosy patients ― would not get it,” said Dr. Zaw Moe Aung, country director of the Leprosy Mission Myanmar, which provides medical assistance to centers such as the Myitta facility.

Malnourishment and poverty affect vast segments of Myanmar’s population of 51 million. Newly recorded leprosy cases average about 3,000 per year here.

“Fifteen percent of the new cases are still identified too late, when preventable symptoms such as loss of sensitivity or claw hands mean nerve functions are compromised,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

In the 1980s, a multidrug therapy arrived on the scene. It proved effective in fighting leprosy around the world and is still the main form of treatment. If patients get this treatment at a point in the disease where their nerves are still repairable, they can avoid permanent disability. But many are cured only after the disease has rendered them unable to walk, write or see.

This treatment, which the World Health Organization began offering for free in 1995, worked wonders in Myanmar ― for a while, anyway. Thanks in part to a global effort, spearheaded by the WHO, to stamp out leprosy, Myanmar was able to significantly reduce the prevalence of the disease. In 2000, the WHO declared that leprosy had been eliminated as a health threat across much of the world. Myanmar, only slightly behind the curve, achieved elimination in 2003.

But “elimination” does not mean a disease is gone completely ― only that it’s been reduced to a manageable level. Even after things reached that point in Myanmar, there was still much work to be done. And unfortunately, worldwide efforts to fight leprosy have stalled.

As in the rest of Southeast Asia, where 74 percent of the world’s leprosy cases occur, the number of new cases in Myanmar is declining very slowly.

“Announcing that it had been ‘eliminated’ sent the wrong signal to the world,” Zaw Moe Aung said. “Donors halted funding and even health workers lost interest ― there was no inspiration for new generations to go and work with leprosy patients.”

“They would flock to HIV, TB, and get doctorates studying these illnesses, while nobody cared about leprosy,” he went on. “But you still need treatment, support for disabled patients and prevention education for the wider community. It might otherwise spread or be detected when it’s too late.”

In Myanmar, public information campaigns featuring writers and celebrities also helped to bring down the number of new cases, and to reduce the stigma that once saw people forcing patients off buses, burning their homes and sending them to live in separate villages ― even after their illness had been treated. But the judgment is still there.

“Self-stigma is also a real problem,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

U Aye Ko, an 80-year-old former magician and a patient at Myitta, says he felt like he needed to cut himself off from the world.

“I did not want my family to become a disgrace,” he said.

U Aye Ko used to perform in theaters all over the country. When he was 50, a red patch that had been on his hip for years started spreading. Leprosy symptoms can take up to 20 years to develop, so when new lesions appeared and his hands eventually lost sensitivity, he decided to leave his home.

“I felt inferior. I preferred to go,” he said. But even though leprosy has deformed his hands, he added, he can still perform the tricks his grandfather taught him, like conjuring flowers from his mouth.

His days of public performances may be over, but his desire to reunite with his family has grown stronger.

“I will try to make contact with them,” U Aye Ko said. “I know that my nephews live in Singapore. I would like to know how they are.”

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to [email protected]. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

When Bullets Fly, These Medics Grab Their Packs And Treat Patients On The Run

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2pglXPQ

0 notes

Text

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

YANGON, Myanmar ― Su Myant Sandar was 17 when she first noticed a red patch on her cheek. At the time, she was working with her girlfriends at a garment factory on the poor outskirts of this city. She covered the spot with a thick layer of thanaka, a traditional plant-based makeup, and continued going to work as normal.

But it was not an ordinary spot. It was the first visible sign of leprosy, a largely forgotten bacterial infection that affects tens of thousands of people every year, mostly in southeast Asia and most of them extremely poor. An ancient disease, leprosy causes skin lesions and nerve damage and can lead to severe disfigurement and disability.

Though curable and not highly contagious, the disease has long carried an intense social stigma, one that used to relegate people with leprosy to the fringes of Myanmar society. Modern treatment has erased some of this stigma, but even those who are cured shoulder a heavy emotional burden.

By the time the lesions spread across her body, Su Myant Sandar was out of a job and isolated from her friends. Already an orphan, she ate by herself every day, with her own fork and glass. Her brother quarreled constantly with his wife about her staying with them. She’d started receiving treatment at a local hospital, but it made her so lonely and exhausted that she stopped going before she was fully healed.

Su Myant Sandar’s relapse, months later, was severe. The disease reappeared in new patches on her skin, while weakness and numbness crept into her hands. She caught tuberculosis around the same time.

Her family decided to send her to the Myitta leprosy asylum, two hours away from Yangon. She’s still there today.

Now 20 years old, Su Myant Sandar is on the 11th month of a yearlong treatment at Myitta. She will be completely cured soon, but her limbs are covered with deep scars and have grown as thin as a child’s. Still, she says she feels “very lucky.” Unlike many other patients at the center, some of whom are in wheelchairs, leprosy didn’t mar her face or paralyze her fingers permanently.

Contrary to popular belief, the disease doesn’t cause body parts to fall off. But in extreme cases, it damages nerves so much that patients won’t feel injuries and might not treat wounds properly, which in turn can lead to infection and amputation. Facial paralysis and blindness may occur, and fingers and toes may curl and shorten. The disease can also destroy nasal cartilage, causing the nose to collapse entirely.

Even though Su Myant Sandar escaped some of leprosy’s most devastating physical complications, she has no dream of a boyfriend or a family in her future.

“A normal man would not want me,” she said in a resigned monotone.

“I don’t want to leave this place ever again,” she added. “I don’t want to go back home ever again. I have an ‘auntie,’ a ‘sister’ and friends here. They are like me. They don’t reject me.”

Su Myant Sandar has plenty in common with the other 130 patients at the Myitta center. They share a background of poverty, malnourishment and fear of an “outside” world that has inflicted on them the deep wounds of abandonment and rejection.

Centers such as Myitta give shelter and food to people who are often unable to provide for themselves due to disability. In the past, people with leprosy often lived around hospitals, either producing alcoholic drinks or begging, or ended up in rundown colonies where people died of malaria in great numbers. But in the bright, Spartan wards of this modern structure, patients can receive visits and move in wheelchairs around the tranquil courtyard.

Scientists believe leprosy is spread when a person carrying the bacteria coughs or sneezes and a healthy person inhales the droplets. Transmission requires prolonged, close exposure, but the odds of contagion are higher among people with compromised immune systems or who live in houses with no ventilation.

“The majority of the population ― even doctors and nurses exposed to leprosy patients ― would not get it,” said Dr. Zaw Moe Aung, country director of the Leprosy Mission Myanmar, which provides medical assistance to centers such as the Myitta facility.

Malnourishment and poverty affect vast segments of Myanmar’s population of 51 million. Newly recorded leprosy cases average about 3,000 per year here.

“Fifteen percent of the new cases are still identified too late, when preventable symptoms such as loss of sensitivity or claw hands mean nerve functions are compromised,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

In the 1980s, a multidrug therapy arrived on the scene. It proved effective in fighting leprosy around the world and is still the main form of treatment. If patients get this treatment at a point in the disease where their nerves are still repairable, they can avoid permanent disability. But many are cured only after the disease has rendered them unable to walk, write or see.

This treatment, which the World Health Organization began offering for free in 1995, worked wonders in Myanmar ― for a while, anyway. Thanks in part to a global effort, spearheaded by the WHO, to stamp out leprosy, Myanmar was able to significantly reduce the prevalence of the disease. In 2000, the WHO declared that leprosy had been eliminated as a health threat across much of the world. Myanmar, only slightly behind the curve, achieved elimination in 2003.

But “elimination” does not mean a disease is gone completely ― only that it’s been reduced to a manageable level. Even after things reached that point in Myanmar, there was still much work to be done. And unfortunately, worldwide efforts to fight leprosy have stalled.

As in the rest of Southeast Asia, where 74 percent of the world’s leprosy cases occur, the number of new cases in Myanmar is declining very slowly.

“Announcing that it had been ‘eliminated’ sent the wrong signal to the world,” Zaw Moe Aung said. “Donors halted funding and even health workers lost interest ― there was no inspiration for new generations to go and work with leprosy patients.”

“They would flock to HIV, TB, and get doctorates studying these illnesses, while nobody cared about leprosy,” he went on. “But you still need treatment, support for disabled patients and prevention education for the wider community. It might otherwise spread or be detected when it’s too late.”

In Myanmar, public information campaigns featuring writers and celebrities also helped to bring down the number of new cases, and to reduce the stigma that once saw people forcing patients off buses, burning their homes and sending them to live in separate villages ― even after their illness had been treated. But the judgment is still there.

“Self-stigma is also a real problem,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

U Aye Ko, an 80-year-old former magician and a patient at Myitta, says he felt like he needed to cut himself off from the world.

“I did not want my family to become a disgrace,” he said.

U Aye Ko used to perform in theaters all over the country. When he was 50, a red patch that had been on his hip for years started spreading. Leprosy symptoms can take up to 20 years to develop, so when new lesions appeared and his hands eventually lost sensitivity, he decided to leave his home.

“I felt inferior. I preferred to go,” he said. But even though leprosy has deformed his hands, he added, he can still perform the tricks his grandfather taught him, like conjuring flowers from his mouth.

His days of public performances may be over, but his desire to reunite with his family has grown stronger.

“I will try to make contact with them,” U Aye Ko said. “I know that my nephews live in Singapore. I would like to know how they are.”

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to [email protected]. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

When Bullets Fly, These Medics Grab Their Packs And Treat Patients On The Run

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2pglXPQ

0 notes

Text

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

YANGON, Myanmar ― Su Myant Sandar was 17 when she first noticed a red patch on her cheek. At the time, she was working with her girlfriends at a garment factory on the poor outskirts of this city. She covered the spot with a thick layer of thanaka, a traditional plant-based makeup, and continued going to work as normal.

But it was not an ordinary spot. It was the first visible sign of leprosy, a largely forgotten bacterial infection that affects tens of thousands of people every year, mostly in southeast Asia and most of them extremely poor. An ancient disease, leprosy causes skin lesions and nerve damage and can lead to severe disfigurement and disability.

Though curable and not highly contagious, the disease has long carried an intense social stigma, one that used to relegate people with leprosy to the fringes of Myanmar society. Modern treatment has erased some of this stigma, but even those who are cured shoulder a heavy emotional burden.

By the time the lesions spread across her body, Su Myant Sandar was out of a job and isolated from her friends. Already an orphan, she ate by herself every day, with her own fork and glass. Her brother quarreled constantly with his wife about her staying with them. She’d started receiving treatment at a local hospital, but it made her so lonely and exhausted that she stopped going before she was fully healed.

Su Myant Sandar’s relapse, months later, was severe. The disease reappeared in new patches on her skin, while weakness and numbness crept into her hands. She caught tuberculosis around the same time.

Her family decided to send her to the Myitta leprosy asylum, two hours away from Yangon. She’s still there today.

Now 20 years old, Su Myant Sandar is on the 11th month of a yearlong treatment at Myitta. She will be completely cured soon, but her limbs are covered with deep scars and have grown as thin as a child’s. Still, she says she feels “very lucky.” Unlike many other patients at the center, some of whom are in wheelchairs, leprosy didn’t mar her face or paralyze her fingers permanently.

Contrary to popular belief, the disease doesn’t cause body parts to fall off. But in extreme cases, it damages nerves so much that patients won’t feel injuries and might not treat wounds properly, which in turn can lead to infection and amputation. Facial paralysis and blindness may occur, and fingers and toes may curl and shorten. The disease can also destroy nasal cartilage, causing the nose to collapse entirely.

Even though Su Myant Sandar escaped some of leprosy’s most devastating physical complications, she has no dream of a boyfriend or a family in her future.

“A normal man would not want me,” she said in a resigned monotone.

“I don’t want to leave this place ever again,” she added. “I don’t want to go back home ever again. I have an ‘auntie,’ a ‘sister’ and friends here. They are like me. They don’t reject me.”

Su Myant Sandar has plenty in common with the other 130 patients at the Myitta center. They share a background of poverty, malnourishment and fear of an “outside” world that has inflicted on them the deep wounds of abandonment and rejection.

Centers such as Myitta give shelter and food to people who are often unable to provide for themselves due to disability. In the past, people with leprosy often lived around hospitals, either producing alcoholic drinks or begging, or ended up in rundown colonies where people died of malaria in great numbers. But in the bright, Spartan wards of this modern structure, patients can receive visits and move in wheelchairs around the tranquil courtyard.

Scientists believe leprosy is spread when a person carrying the bacteria coughs or sneezes and a healthy person inhales the droplets. Transmission requires prolonged, close exposure, but the odds of contagion are higher among people with compromised immune systems or who live in houses with no ventilation.

“The majority of the population ― even doctors and nurses exposed to leprosy patients ― would not get it,” said Dr. Zaw Moe Aung, country director of the Leprosy Mission Myanmar, which provides medical assistance to centers such as the Myitta facility.

Malnourishment and poverty affect vast segments of Myanmar’s population of 51 million. Newly recorded leprosy cases average about 3,000 per year here.

“Fifteen percent of the new cases are still identified too late, when preventable symptoms such as loss of sensitivity or claw hands mean nerve functions are compromised,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

In the 1980s, a multidrug therapy arrived on the scene. It proved effective in fighting leprosy around the world and is still the main form of treatment. If patients get this treatment at a point in the disease where their nerves are still repairable, they can avoid permanent disability. But many are cured only after the disease has rendered them unable to walk, write or see.

This treatment, which the World Health Organization began offering for free in 1995, worked wonders in Myanmar ― for a while, anyway. Thanks in part to a global effort, spearheaded by the WHO, to stamp out leprosy, Myanmar was able to significantly reduce the prevalence of the disease. In 2000, the WHO declared that leprosy had been eliminated as a health threat across much of the world. Myanmar, only slightly behind the curve, achieved elimination in 2003.

But “elimination” does not mean a disease is gone completely ― only that it’s been reduced to a manageable level. Even after things reached that point in Myanmar, there was still much work to be done. And unfortunately, worldwide efforts to fight leprosy have stalled.

As in the rest of Southeast Asia, where 74 percent of the world’s leprosy cases occur, the number of new cases in Myanmar is declining very slowly.

“Announcing that it had been ‘eliminated’ sent the wrong signal to the world,” Zaw Moe Aung said. “Donors halted funding and even health workers lost interest ― there was no inspiration for new generations to go and work with leprosy patients.”

“They would flock to HIV, TB, and get doctorates studying these illnesses, while nobody cared about leprosy,” he went on. “But you still need treatment, support for disabled patients and prevention education for the wider community. It might otherwise spread or be detected when it’s too late.”

In Myanmar, public information campaigns featuring writers and celebrities also helped to bring down the number of new cases, and to reduce the stigma that once saw people forcing patients off buses, burning their homes and sending them to live in separate villages ― even after their illness had been treated. But the judgment is still there.

“Self-stigma is also a real problem,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

U Aye Ko, an 80-year-old former magician and a patient at Myitta, says he felt like he needed to cut himself off from the world.

“I did not want my family to become a disgrace,” he said.

U Aye Ko used to perform in theaters all over the country. When he was 50, a red patch that had been on his hip for years started spreading. Leprosy symptoms can take up to 20 years to develop, so when new lesions appeared and his hands eventually lost sensitivity, he decided to leave his home.

“I felt inferior. I preferred to go,” he said. But even though leprosy has deformed his hands, he added, he can still perform the tricks his grandfather taught him, like conjuring flowers from his mouth.

His days of public performances may be over, but his desire to reunite with his family has grown stronger.

“I will try to make contact with them,” U Aye Ko said. “I know that my nephews live in Singapore. I would like to know how they are.”

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to [email protected]. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

When Bullets Fly, These Medics Grab Their Packs And Treat Patients On The Run

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2pglXPQ

0 notes

Text

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

YANGON, Myanmar ― Su Myant Sandar was 17 when she first noticed a red patch on her cheek. At the time, she was working with her girlfriends at a garment factory on the poor outskirts of this city. She covered the spot with a thick layer of thanaka, a traditional plant-based makeup, and continued going to work as normal.

But it was not an ordinary spot. It was the first visible sign of leprosy, a largely forgotten bacterial infection that affects tens of thousands of people every year, mostly in southeast Asia and most of them extremely poor. An ancient disease, leprosy causes skin lesions and nerve damage and can lead to severe disfigurement and disability.

Though curable and not highly contagious, the disease has long carried an intense social stigma, one that used to relegate people with leprosy to the fringes of Myanmar society. Modern treatment has erased some of this stigma, but even those who are cured shoulder a heavy emotional burden.

By the time the lesions spread across her body, Su Myant Sandar was out of a job and isolated from her friends. Already an orphan, she ate by herself every day, with her own fork and glass. Her brother quarreled constantly with his wife about her staying with them. She’d started receiving treatment at a local hospital, but it made her so lonely and exhausted that she stopped going before she was fully healed.

Su Myant Sandar’s relapse, months later, was severe. The disease reappeared in new patches on her skin, while weakness and numbness crept into her hands. She caught tuberculosis around the same time.

Her family decided to send her to the Myitta leprosy asylum, two hours away from Yangon. She’s still there today.

Now 20 years old, Su Myant Sandar is on the 11th month of a yearlong treatment at Myitta. She will be completely cured soon, but her limbs are covered with deep scars and have grown as thin as a child’s. Still, she says she feels “very lucky.” Unlike many other patients at the center, some of whom are in wheelchairs, leprosy didn’t mar her face or paralyze her fingers permanently.

Contrary to popular belief, the disease doesn’t cause body parts to fall off. But in extreme cases, it damages nerves so much that patients won’t feel injuries and might not treat wounds properly, which in turn can lead to infection and amputation. Facial paralysis and blindness may occur, and fingers and toes may curl and shorten. The disease can also destroy nasal cartilage, causing the nose to collapse entirely.

Even though Su Myant Sandar escaped some of leprosy’s most devastating physical complications, she has no dream of a boyfriend or a family in her future.

“A normal man would not want me,” she said in a resigned monotone.

“I don’t want to leave this place ever again,” she added. “I don’t want to go back home ever again. I have an ‘auntie,’ a ‘sister’ and friends here. They are like me. They don’t reject me.”

Su Myant Sandar has plenty in common with the other 130 patients at the Myitta center. They share a background of poverty, malnourishment and fear of an “outside” world that has inflicted on them the deep wounds of abandonment and rejection.

Centers such as Myitta give shelter and food to people who are often unable to provide for themselves due to disability. In the past, people with leprosy often lived around hospitals, either producing alcoholic drinks or begging, or ended up in rundown colonies where people died of malaria in great numbers. But in the bright, Spartan wards of this modern structure, patients can receive visits and move in wheelchairs around the tranquil courtyard.

Scientists believe leprosy is spread when a person carrying the bacteria coughs or sneezes and a healthy person inhales the droplets. Transmission requires prolonged, close exposure, but the odds of contagion are higher among people with compromised immune systems or who live in houses with no ventilation.

“The majority of the population ― even doctors and nurses exposed to leprosy patients ― would not get it,” said Dr. Zaw Moe Aung, country director of the Leprosy Mission Myanmar, which provides medical assistance to centers such as the Myitta facility.

Malnourishment and poverty affect vast segments of Myanmar’s population of 51 million. Newly recorded leprosy cases average about 3,000 per year here.

“Fifteen percent of the new cases are still identified too late, when preventable symptoms such as loss of sensitivity or claw hands mean nerve functions are compromised,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

In the 1980s, a multidrug therapy arrived on the scene. It proved effective in fighting leprosy around the world and is still the main form of treatment. If patients get this treatment at a point in the disease where their nerves are still repairable, they can avoid permanent disability. But many are cured only after the disease has rendered them unable to walk, write or see.

This treatment, which the World Health Organization began offering for free in 1995, worked wonders in Myanmar ― for a while, anyway. Thanks in part to a global effort, spearheaded by the WHO, to stamp out leprosy, Myanmar was able to significantly reduce the prevalence of the disease. In 2000, the WHO declared that leprosy had been eliminated as a health threat across much of the world. Myanmar, only slightly behind the curve, achieved elimination in 2003.

But “elimination” does not mean a disease is gone completely ― only that it’s been reduced to a manageable level. Even after things reached that point in Myanmar, there was still much work to be done. And unfortunately, worldwide efforts to fight leprosy have stalled.

As in the rest of Southeast Asia, where 74 percent of the world’s leprosy cases occur, the number of new cases in Myanmar is declining very slowly.

“Announcing that it had been ‘eliminated’ sent the wrong signal to the world,” Zaw Moe Aung said. “Donors halted funding and even health workers lost interest ― there was no inspiration for new generations to go and work with leprosy patients.”

“They would flock to HIV, TB, and get doctorates studying these illnesses, while nobody cared about leprosy,” he went on. “But you still need treatment, support for disabled patients and prevention education for the wider community. It might otherwise spread or be detected when it’s too late.”

In Myanmar, public information campaigns featuring writers and celebrities also helped to bring down the number of new cases, and to reduce the stigma that once saw people forcing patients off buses, burning their homes and sending them to live in separate villages ― even after their illness had been treated. But the judgment is still there.

“Self-stigma is also a real problem,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

U Aye Ko, an 80-year-old former magician and a patient at Myitta, says he felt like he needed to cut himself off from the world.

“I did not want my family to become a disgrace,” he said.

U Aye Ko used to perform in theaters all over the country. When he was 50, a red patch that had been on his hip for years started spreading. Leprosy symptoms can take up to 20 years to develop, so when new lesions appeared and his hands eventually lost sensitivity, he decided to leave his home.

“I felt inferior. I preferred to go,” he said. But even though leprosy has deformed his hands, he added, he can still perform the tricks his grandfather taught him, like conjuring flowers from his mouth.

His days of public performances may be over, but his desire to reunite with his family has grown stronger.

“I will try to make contact with them,” U Aye Ko said. “I know that my nephews live in Singapore. I would like to know how they are.”

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to [email protected]. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

When Bullets Fly, These Medics Grab Their Packs And Treat Patients On The Run

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2pglXPQ

0 notes

Text

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

YANGON, Myanmar ― Su Myant Sandar was 17 when she first noticed a red patch on her cheek. At the time, she was working with her girlfriends at a garment factory on the poor outskirts of this city. She covered the spot with a thick layer of thanaka, a traditional plant-based makeup, and continued going to work as normal.

But it was not an ordinary spot. It was the first visible sign of leprosy, a largely forgotten bacterial infection that affects tens of thousands of people every year, mostly in southeast Asia and most of them extremely poor. An ancient disease, leprosy causes skin lesions and nerve damage and can lead to severe disfigurement and disability.

Though curable and not highly contagious, the disease has long carried an intense social stigma, one that used to relegate people with leprosy to the fringes of Myanmar society. Modern treatment has erased some of this stigma, but even those who are cured shoulder a heavy emotional burden.

By the time the lesions spread across her body, Su Myant Sandar was out of a job and isolated from her friends. Already an orphan, she ate by herself every day, with her own fork and glass. Her brother quarreled constantly with his wife about her staying with them. She’d started receiving treatment at a local hospital, but it made her so lonely and exhausted that she stopped going before she was fully healed.

Su Myant Sandar’s relapse, months later, was severe. The disease reappeared in new patches on her skin, while weakness and numbness crept into her hands. She caught tuberculosis around the same time.

Her family decided to send her to the Myitta leprosy asylum, two hours away from Yangon. She’s still there today.

Now 20 years old, Su Myant Sandar is on the 11th month of a yearlong treatment at Myitta. She will be completely cured soon, but her limbs are covered with deep scars and have grown as thin as a child’s. Still, she says she feels “very lucky.” Unlike many other patients at the center, some of whom are in wheelchairs, leprosy didn’t mar her face or paralyze her fingers permanently.

Contrary to popular belief, the disease doesn’t cause body parts to fall off. But in extreme cases, it damages nerves so much that patients won’t feel injuries and might not treat wounds properly, which in turn can lead to infection and amputation. Facial paralysis and blindness may occur, and fingers and toes may curl and shorten. The disease can also destroy nasal cartilage, causing the nose to collapse entirely.

Even though Su Myant Sandar escaped some of leprosy’s most devastating physical complications, she has no dream of a boyfriend or a family in her future.

“A normal man would not want me,” she said in a resigned monotone.

“I don’t want to leave this place ever again,” she added. “I don’t want to go back home ever again. I have an ‘auntie,’ a ‘sister’ and friends here. They are like me. They don’t reject me.”

Su Myant Sandar has plenty in common with the other 130 patients at the Myitta center. They share a background of poverty, malnourishment and fear of an “outside” world that has inflicted on them the deep wounds of abandonment and rejection.

Centers such as Myitta give shelter and food to people who are often unable to provide for themselves due to disability. In the past, people with leprosy often lived around hospitals, either producing alcoholic drinks or begging, or ended up in rundown colonies where people died of malaria in great numbers. But in the bright, Spartan wards of this modern structure, patients can receive visits and move in wheelchairs around the tranquil courtyard.

Scientists believe leprosy is spread when a person carrying the bacteria coughs or sneezes and a healthy person inhales the droplets. Transmission requires prolonged, close exposure, but the odds of contagion are higher among people with compromised immune systems or who live in houses with no ventilation.

“The majority of the population ― even doctors and nurses exposed to leprosy patients ― would not get it,” said Dr. Zaw Moe Aung, country director of the Leprosy Mission Myanmar, which provides medical assistance to centers such as the Myitta facility.

Malnourishment and poverty affect vast segments of Myanmar’s population of 51 million. Newly recorded leprosy cases average about 3,000 per year here.

“Fifteen percent of the new cases are still identified too late, when preventable symptoms such as loss of sensitivity or claw hands mean nerve functions are compromised,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

In the 1980s, a multidrug therapy arrived on the scene. It proved effective in fighting leprosy around the world and is still the main form of treatment. If patients get this treatment at a point in the disease where their nerves are still repairable, they can avoid permanent disability. But many are cured only after the disease has rendered them unable to walk, write or see.

This treatment, which the World Health Organization began offering for free in 1995, worked wonders in Myanmar ― for a while, anyway. Thanks in part to a global effort, spearheaded by the WHO, to stamp out leprosy, Myanmar was able to significantly reduce the prevalence of the disease. In 2000, the WHO declared that leprosy had been eliminated as a health threat across much of the world. Myanmar, only slightly behind the curve, achieved elimination in 2003.

But “elimination” does not mean a disease is gone completely ― only that it’s been reduced to a manageable level. Even after things reached that point in Myanmar, there was still much work to be done. And unfortunately, worldwide efforts to fight leprosy have stalled.

As in the rest of Southeast Asia, where 74 percent of the world’s leprosy cases occur, the number of new cases in Myanmar is declining very slowly.

“Announcing that it had been ‘eliminated’ sent the wrong signal to the world,” Zaw Moe Aung said. “Donors halted funding and even health workers lost interest ― there was no inspiration for new generations to go and work with leprosy patients.”

“They would flock to HIV, TB, and get doctorates studying these illnesses, while nobody cared about leprosy,” he went on. “But you still need treatment, support for disabled patients and prevention education for the wider community. It might otherwise spread or be detected when it’s too late.”

In Myanmar, public information campaigns featuring writers and celebrities also helped to bring down the number of new cases, and to reduce the stigma that once saw people forcing patients off buses, burning their homes and sending them to live in separate villages ― even after their illness had been treated. But the judgment is still there.

“Self-stigma is also a real problem,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

U Aye Ko, an 80-year-old former magician and a patient at Myitta, says he felt like he needed to cut himself off from the world.

“I did not want my family to become a disgrace,” he said.

U Aye Ko used to perform in theaters all over the country. When he was 50, a red patch that had been on his hip for years started spreading. Leprosy symptoms can take up to 20 years to develop, so when new lesions appeared and his hands eventually lost sensitivity, he decided to leave his home.

“I felt inferior. I preferred to go,” he said. But even though leprosy has deformed his hands, he added, he can still perform the tricks his grandfather taught him, like conjuring flowers from his mouth.

His days of public performances may be over, but his desire to reunite with his family has grown stronger.

“I will try to make contact with them,” U Aye Ko said. “I know that my nephews live in Singapore. I would like to know how they are.”

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to [email protected]. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

When Bullets Fly, These Medics Grab Their Packs And Treat Patients On The Run

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2pglXPQ

0 notes

Text

'A Normal Man Would Not Want Me': A Heartbreaking Look At Leprosy In 2017

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

YANGON, Myanmar ― Su Myant Sandar was 17 when she first noticed a red patch on her cheek. At the time, she was working with her girlfriends at a garment factory on the poor outskirts of this city. She covered the spot with a thick layer of thanaka, a traditional plant-based makeup, and continued going to work as normal.

But it was not an ordinary spot. It was the first visible sign of leprosy, a largely forgotten bacterial infection that affects tens of thousands of people every year, mostly in southeast Asia and most of them extremely poor. An ancient disease, leprosy causes skin lesions and nerve damage and can lead to severe disfigurement and disability.

Though curable and not highly contagious, the disease has long carried an intense social stigma, one that used to relegate people with leprosy to the fringes of Myanmar society. Modern treatment has erased some of this stigma, but even those who are cured shoulder a heavy emotional burden.

By the time the lesions spread across her body, Su Myant Sandar was out of a job and isolated from her friends. Already an orphan, she ate by herself every day, with her own fork and glass. Her brother quarreled constantly with his wife about her staying with them. She’d started receiving treatment at a local hospital, but it made her so lonely and exhausted that she stopped going before she was fully healed.

Su Myant Sandar’s relapse, months later, was severe. The disease reappeared in new patches on her skin, while weakness and numbness crept into her hands. She caught tuberculosis around the same time.

Her family decided to send her to the Myitta leprosy asylum, two hours away from Yangon. She’s still there today.

Now 20 years old, Su Myant Sandar is on the 11th month of a yearlong treatment at Myitta. She will be completely cured soon, but her limbs are covered with deep scars and have grown as thin as a child’s. Still, she says she feels “very lucky.” Unlike many other patients at the center, some of whom are in wheelchairs, leprosy didn’t mar her face or paralyze her fingers permanently.

Contrary to popular belief, the disease doesn’t cause body parts to fall off. But in extreme cases, it damages nerves so much that patients won’t feel injuries and might not treat wounds properly, which in turn can lead to infection and amputation. Facial paralysis and blindness may occur, and fingers and toes may curl and shorten. The disease can also destroy nasal cartilage, causing the nose to collapse entirely.

Even though Su Myant Sandar escaped some of leprosy’s most devastating physical complications, she has no dream of a boyfriend or a family in her future.

“A normal man would not want me,” she said in a resigned monotone.

“I don’t want to leave this place ever again,” she added. “I don’t want to go back home ever again. I have an ‘auntie,’ a ‘sister’ and friends here. They are like me. They don’t reject me.”

Su Myant Sandar has plenty in common with the other 130 patients at the Myitta center. They share a background of poverty, malnourishment and fear of an “outside” world that has inflicted on them the deep wounds of abandonment and rejection.

Centers such as Myitta give shelter and food to people who are often unable to provide for themselves due to disability. In the past, people with leprosy often lived around hospitals, either producing alcoholic drinks or begging, or ended up in rundown colonies where people died of malaria in great numbers. But in the bright, Spartan wards of this modern structure, patients can receive visits and move in wheelchairs around the tranquil courtyard.

Scientists believe leprosy is spread when a person carrying the bacteria coughs or sneezes and a healthy person inhales the droplets. Transmission requires prolonged, close exposure, but the odds of contagion are higher among people with compromised immune systems or who live in houses with no ventilation.

“The majority of the population ― even doctors and nurses exposed to leprosy patients ― would not get it,” said Dr. Zaw Moe Aung, country director of the Leprosy Mission Myanmar, which provides medical assistance to centers such as the Myitta facility.

Malnourishment and poverty affect vast segments of Myanmar’s population of 51 million. Newly recorded leprosy cases average about 3,000 per year here.

“Fifteen percent of the new cases are still identified too late, when preventable symptoms such as loss of sensitivity or claw hands mean nerve functions are compromised,” Zaw Moe Aung said.

In the 1980s, a multidrug therapy arrived on the scene. It proved effective in fighting leprosy around the world and is still the main form of treatment. If patients get this treatment at a point in the disease where their nerves are still repairable, they can avoid permanent disability. But many are cured only after the disease has rendered them unable to walk, write or see.