#Xiaoxue Tang

Text

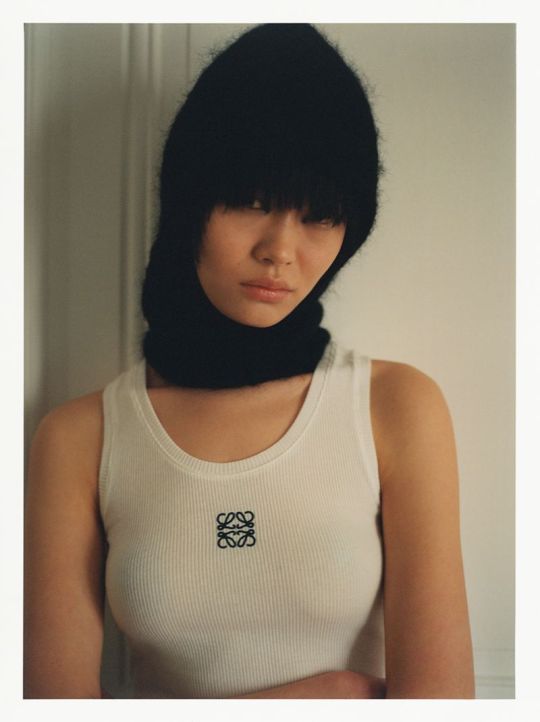

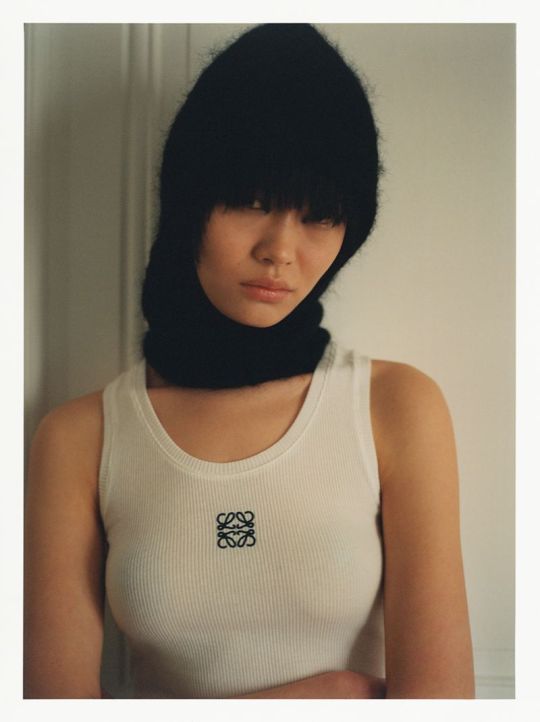

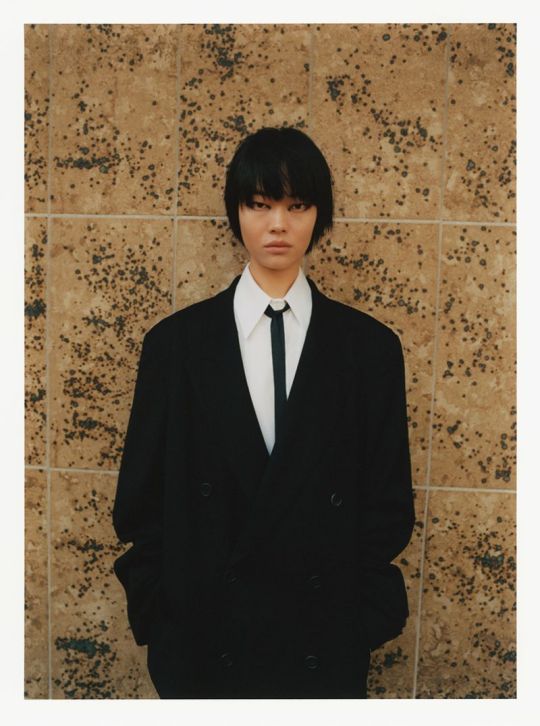

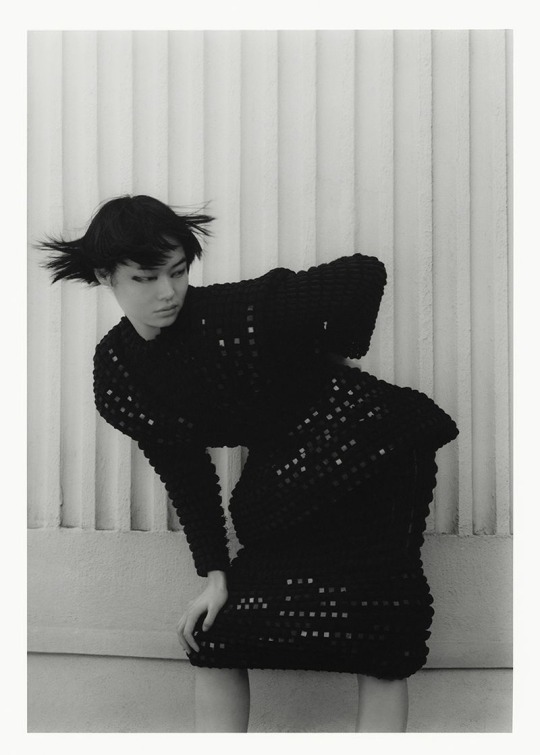

Xiaoxue Tang by Nina Raasch for METAL Magazine January 2024

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

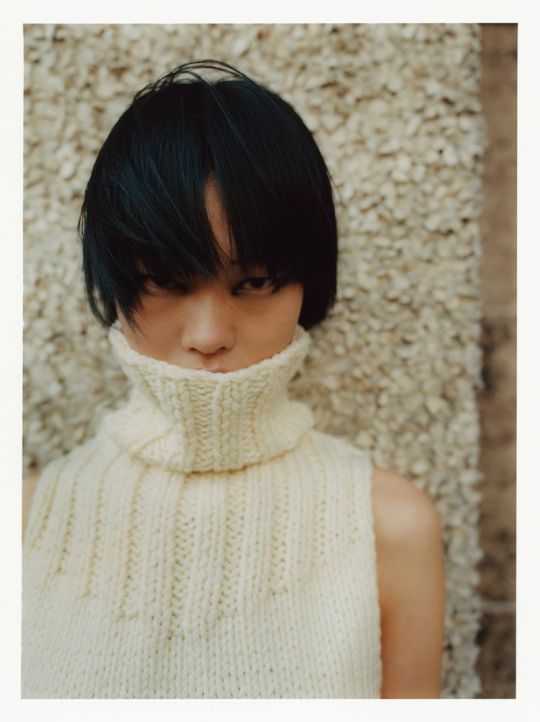

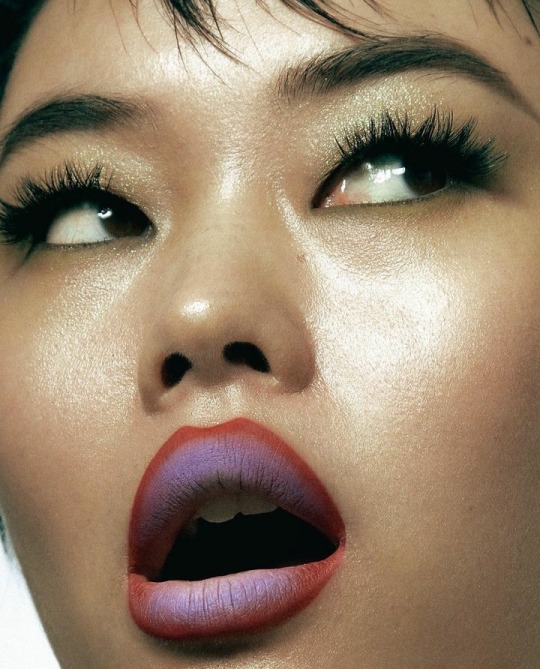

Xiaoxue Tang photographed by Olivia Ezechukwu, makeup by David Gillers

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

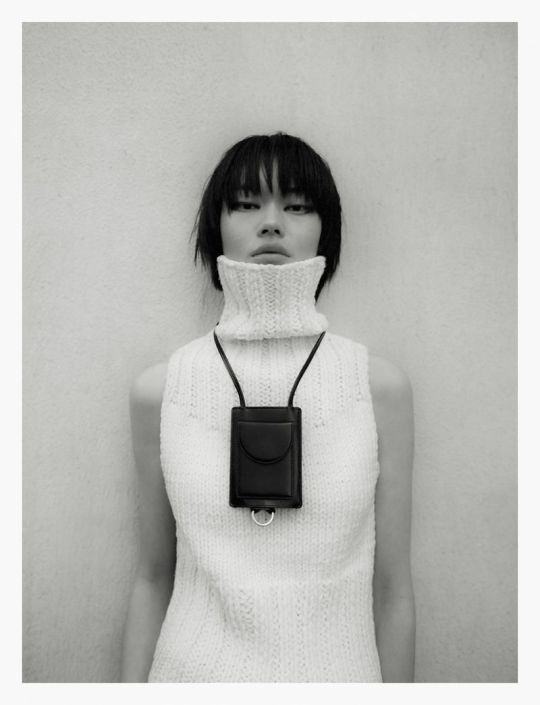

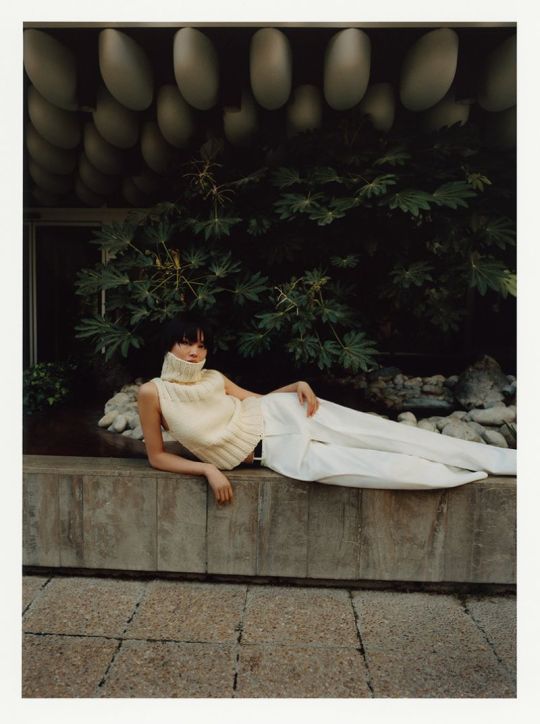

Xiaoxue Tang by Nina Raasch for Metal Magazine January 2024

Saskia Jung (Fashion Editor/Stylist), Hicham Ababsa (Makeup Artist)

159 notes

·

View notes

Photo

https://fashionfav.com/fashion-photography/xiaoxue-tang-kulesza-pik-wrpd-magazine/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

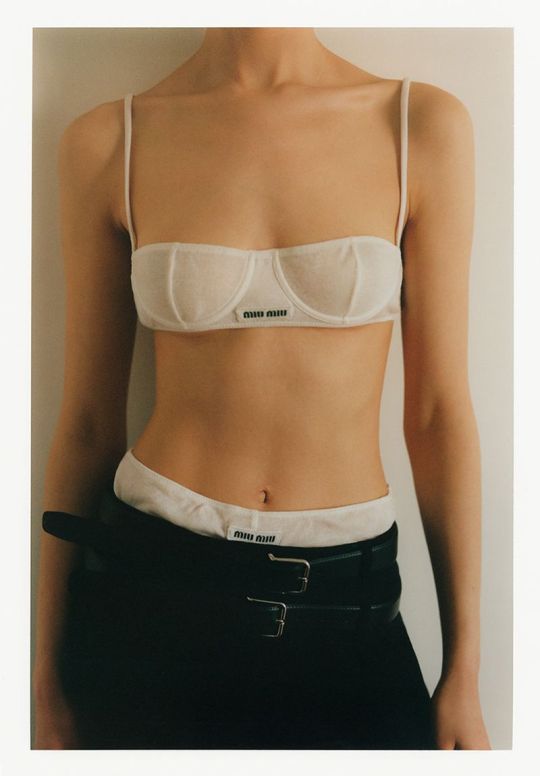

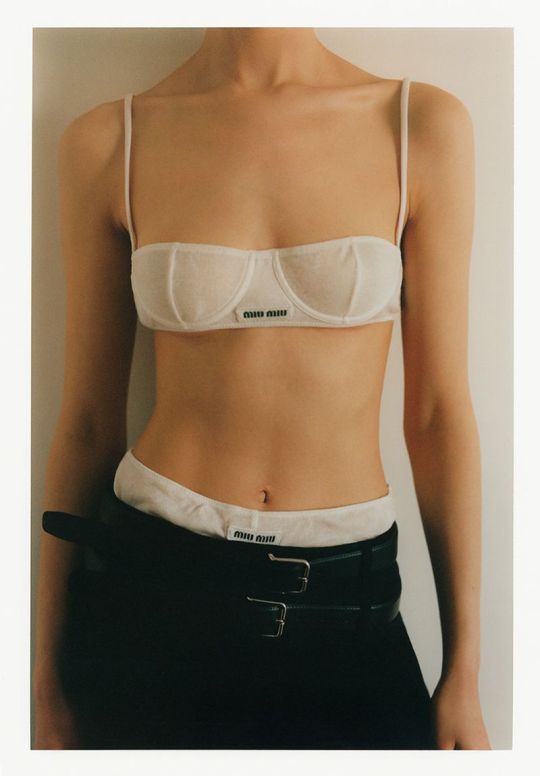

ㅤㅤㅤ

Xiaoxue Tang photographed by Agnieszka Kulesza and Lukasz for WRPD Magazine, issue 10.

STYLIST: Johanna Ankelhed

HAIR: Andrea Idini

MAKEUP: Kamila Vay

CLOTHING: Bra and underwear by Miu Miu, skirt and belt by The Frankie Shop.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Xiaoxue Tang by Agnieszka Kulesza & Lukasz Pik for WRPD

stylist JOHANNA ANKELHED

make up KAMILA VAY

hair ANDREA IDINI

1 note

·

View note

Photo

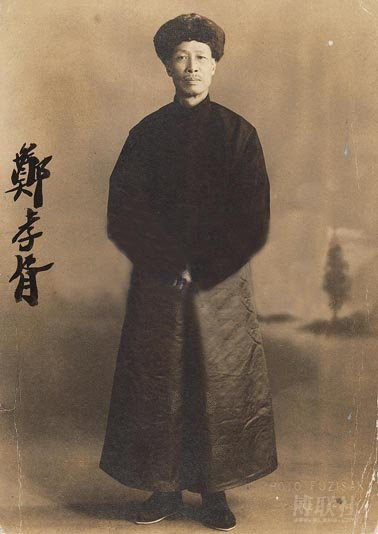

Figure 1. Zheng Xiaoxu’s Portrait (from The Mad Monarchist)

Graduate Research: Chinese Scroll and Fan Work, Part 9

This week we turn our eye to two undated couplets (Figures 2 and 3) by Chinese statesman, diplomat, and calligrapher Zheng Xiaoxu (1860-1938, Figure 1) from our Zhou Cezong Collection of Chinese scroll and fan work.

According to celebrated Chinese writer Lin Yutang (1895-1976, twice nominated for Nobel Prize in Literature), in appreciating Chinese calligraphy, “the meaning is entirely forgotten, and the lines and forms are appreciated in and for themselves.” Thus, let’s skip the literal meaning of these two couplets and just focus on their lines and structures. And hopefully, this focus will help us to date them.

Figure 2. UWM Special Collections (cs 000004)

Figure 3. UWM Special Collections (cs 000054)

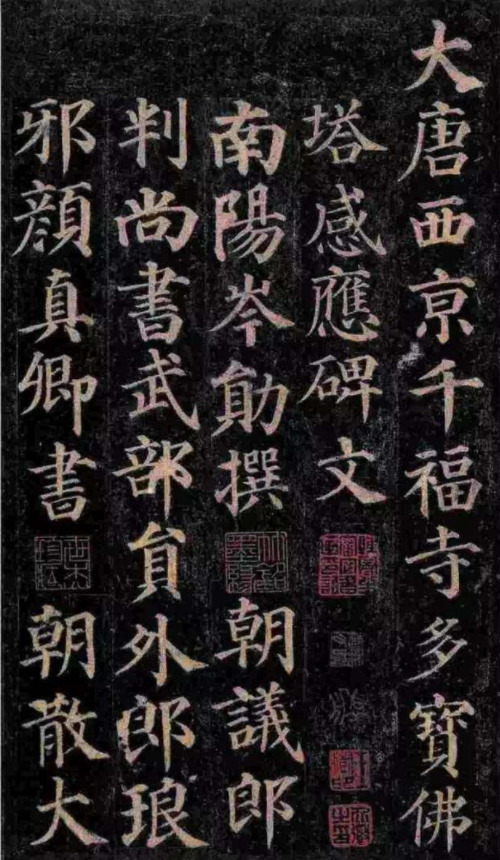

In 1889, Zheng became the protégé of Weng Tonghe (1830-1904), who was Guanxu Emperor’s teacher and one of the most supportive figures of the Hundred Days’ Reform. Influenced by Weng’s artistic taste, Zheng regarded the calligraphy of Tang Dynasty calligrapher Yan Zhenqing (709-785) as a model. In one Zheng’s early calligraphic examples (Figure 4), he exhibited a distinctive, plump, and powerful stroke with a well-knit, balanced structure, which is similar to Yan’s Record of Duobao Pagoda (Figure 5, the forefather of brushwork in standard writing) written in 752. In addition, Zheng imitated Yan’s round brush by adopting “hiding” and “protecting” movement of the brush tip (according to ancient calligraphic theorist Cai Yong, calligraphers should “hide the head” and “protect the tail” of the brushstroke). However, because the turn and thrust is limited, the image is static and frontal, confined to a flat linear schema, and showing rigidity and lassitude.

Figure 4. Zheng’s Early Calligraphy (from this source)

Figure 5. Yan Zhenqing’s Record of Duobao Pagoda (from this source)

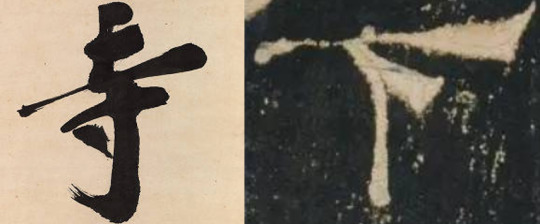

Immediately after Xinhai Revolution in 1911, Zheng spent some time in Shanghai with his boon companions such as Chen Sanli, whom I discussed in a previous post, and Shen Zengzhi, whose cursive hanging scroll is also preserved in our Zhou Cezong Collection. During this period, he maintained an eclectic interest in ancient calligraphic rubbings, such as those from stone inscriptions, epitaphs, Buddhist votive stelae, and cliff engravings created in the Han (202 BC-220 AD) and Northern Dynasties (386-581). Our first couplet in Figure 2 is the epitome of his inclusive studies of the stelae. For instance, the longest horizontal stroke of 寺 (Figure 6) presents a dramatic thinning-and-thickening brush movement, which is akin to brush style of the horizontal line in下(Figure 7) from the Stele on Ritual Implements in the Confucian Temple (Liqi Stele, dated 156 CE). According to Yang Shoujing (1839-1915), whose work is also preserved in our collection, this stele has an eccentric instability concealed in the level-headed stability; and a strict denseness hidden in the elegant sparseness. Zheng’s 寺 is the symbol of this contradictory yet complementary comment. Another example of Zheng’s cross-fertilization could be detected in the character “分” and “明” in Figure 8. The rigid 丿 in “分”, and the rugged 𠃌 in “明” can find similar genealogical traits from their counterparts in Figure 9, which is from Yang Dayan Zao Xiang Ji created around 506 AD. Here, Zheng’s previous flat schema has been transformed to some contrasting variations in a sense of two-dimensionality, bringing vitality to the works. Nevertheless, the rigidity still permeates; and ruggedness is also his Achilles’s heel, indicating a smidgen of strenuousness, which is at variance with Chinese artistic standard of naturalness.

Figure 6: Detail from Figure 2. Figure 7: From Liqi Stele (Palace Museum Collection)

Figure 8: Detail from Figure 2. Figure 9: From Yang Dayan (Harvard Collection).

From 1906 to 1907, during the excavation in the deserts of Northern China, Sir Marc Aurel Stein found a group of wooden slips with calligraphic inscriptions written around 98 BC. In 1912, his friend Édouard Émmannuel Chavannes sent the copy of these slips to Luo Zhenyu (1866-1940), whose couplet scroll in Oracle Bone script is also preserved in our Zhou Cezong Collection. Luo invited Wang Guowei (1877-1927, Liang Qichao’s friend), a great sinologist, to collate, edit, and interpret those slips, which became the famous monograph entitled Liu Sha Zhui Jian (The Lost Wooden Slips Excavated in the Flowing Sands) published in 1914.

When Zheng saw this publication, he was enchanted by the calligraphic values of these slips, as he contended that with the finding of these slips, the secrecy of calligraphy would be thoroughly revealed. Generally speaking, compared with the standardized clerical writing in Figure 7, the running or cursive characters on these slips were rendered with undulation and flexibility (see Figure 10 and 11), devoid of axial balance and austere sublimity. By turning and flicking the brush in a silent pirouette on the paper, the slip writer constantly changed in speed and direction, suggesting a strong foreshortening and movement in space. This untrammeled style significantly enlivens Zheng’s artistic idioms. In Figure 12, the slanting angle and the flaring, wavelike motion of the second horizontal stroke bears uncanny resemblance to those of the first horizontal stroke in Figure 10. The brush is fully articulated in a vivacious spontaneity, carrying a natural three-dimensionality.

(From left to right) Figure 10: From Luo Zhenyu, Liu Sha Zhui Jian, p. 65. Figure 11: From Liu Sha Zhui Jian, p. 64. Figure 12: Detail from Figure 3.

From these three works, Zheng shows his audience the evolution of his mimetic representation. For the first phrase (Figure 4), his imitation of Yan was restricted by insipid flatness and slight flexure. After 1911, his exploration to ancient stele rubbings (Figure 2) gave his works a contrasting vitality, though the rigidity still lingers. For the final phrase (Figure 3), the pristine style of the wooden slips provided him a fresh impetus to awaken his vivacity, creating organic relationship in the image.

Figure 13. Three Greek Statues (from ca. 560 BC to 480 BC)

From Wen C. Fong, Art as History: Calligraphy and Painting as One (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 113.

The art historian E. H. Gombrich once made a similar-style comparisons for a group of ancient Greek statues (Figure 13). Naming them as the representation of the “Greek miracle” which illustrated the advancement of Western European civilization, he indicated in pictorial representation, archaic art began from restricted frontal schema, and then moved to the gradual adjustment to the natural appearances. This phenomenon can be equally applied to analyze Zheng’s work, which could be seen as his gradual accumulation of corrections due to the observation of ancient artworks.

Chinese art historian Wen C. Fong proposed the possible reason for this phenomenon. He noted that the disillusionment of the ancient literati with Chinese politics made them “turn away from the world of human affairs” and sought spiritual solace in the pursuit of artistic and literary expression. The impulse to express themselves in art led to the enlivening of Chinese art and civilization. Zheng is the exemplar of this explanation. He was once a most celebrated constitutionalist in the late Qing. After 1911, he lived in Shanghai as a loyalist to the defunct Qing Dynasty until February 1924, when he went to the Forbidden City to serve as a trusted advisor to Puyi (the last Chinese emperor, 1906-1967). Within these thirteen years, he became disillusioned with politics, and began to regard art as his safety valve, thereby pushing the boundaries of his artistic practices.

From these analyses, we can hypothesize that these two couplets in Special Collections were created during the same period of time (1911-1924). Figure 2 was created first, foretelling the coming of the more mature style in Figure 3. Most importantly, these analyses give us a good example to see how the student and scholar of Chinese calligraphy may use brushstroke and structure as evidence to evaluate, authenticate, and date artworks.

After Puyi and Zheng were evicted from the palace in November 1924, they settled in the Japanese concession of Tianjin. In 1931, under Zheng’s arrangement, Puyi went to Manchuria and became the leader of the Manchurian state, Manchukuo. Zheng became the regime’s Prime Minister with Japanese support. This collaboration with the Japanese tarnished the reputation of Zheng’s previous political and artistic achievements.

– Jingwei Zeng, Special Collections graduate researcher.

#graduate research#Jingwei#Chinese scrolls#Chinese calligraphy#Chinese art#Zheng Xiaoxu#Yan Zhenqing#Chinese politics#calligraphy#art history#couplet#Zhou Cezong Collection#Tse-Tsung Chow Collection

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

China: 2022 AFC Women's Asian Cup Champions

Navi Mumbai: China PR came from two goals down to defeat Korea Republic 3-2 in a pulsating AFC Women's Asian Cup India 2022™ final at the D.Y. Patil Stadium in Navi Mumbai on Sunday.

Korea Republic looked to be cruising to their first crown after taking a 2-0 lead at half-time but China PR fought back after the break through goals from Tang Jiali, Zhang Linyan and Xiao Yuyi - who netted the winner deep into added time to seal her side a record-extending ninth title.

China PR head coach Shui Qingxia hailed her players’ performance in capturing their historic ninth title.

“This is the most critical moment for China PR women’s football,” said Shui. “Despite trailing 2-0 my players showed determination to fight back. I like to thank all the players for winning the title but they also won it for themselves.”

Korea Republic head coach Colin Bell was proud of his players despite missing out on their first title.

"I'm proud of the players, I told them that after the match," said Bell. "We need to keep improving and not let this defeat diminish our spirit. We're bitterly disappointed. We need to be stronger mentally. The penalty against us, took our concentration away."

China PR entered the final chasing their first title since 2006 against a Korea Republic side who had never laid their hands on the coveted trophy.

China PR, unbeaten in seven previous meetings with Korea Republic, started the game brightly and had the first look at goal within seconds when Wu Chengshu played the ball to Tang Jiali just above the area, but the midfielder’s effort was easily dealt with by Korea Republic goalkeeper Kim Jung-mi.

China PR continued to press with Zhang Xin trying from 35 yards out while Wang Shuang saw her effort in the 10th minute saved by Kim.

Korea Republic began to see more of the ball as the half progressed and were rewarded with their first look at goal in the 27th minute, with Lee Geum-min breaking into the box before sending a cross to Choe Yu-Ri to score the 100th goal of the tournament.

With Korea Republic in the ascendancy, China PR survived a scare at the half-hour mark, goalkeeper Zhou Yu pulling off a point-blank save to deny Lim Seon-Joo’s header off a free-kick.

China PR, however, suffered more woe in the closing stages of the first half when a VAR review saw Korea Republic awarded a penalty for Yao Lingwei’s handball, with Ji So-yun converting from the spot.

China PR head coach Shui sent on Xiao Yuyi and Zhang Rui at the start of the second half to force their way back into the game but Korea Republic gave them little room to operate in the early stages.

China PR, however, received a lifeline when they were awarded a penalty for Lee Young-ju’s handball, with Tang Jiali netting from the spot in the 68th minute.

Boosted by the goal, China PR began to dictate play and drew level four minutes later thanks to some poor defending by Korea Republic.

Goalscorer Tang did well to beat two Korea Republic defenders before sending a delightful cross into the six-yard-box for an unmarked Zhang Linyan to nod home the equaliser.

Korea Republic could have then won it at the death with Zhou Yu pulling off a one handed save before defender Wang Xiaoxue blocked Son Hwa-Yeon’s effort.

Having escaped, China PR broke Korea Republic's hearts in added time with Xiao Yuyi stunningly finishing off Wang Shanshan’s pass as a record-extending ninth title was sealed.

0 notes

Text

Talking about the people in the Ming Dynasty, it was known that Tang Xianzu died of syphilis.

The reason for the death of Tang Xianzu has always been that Xu Yufang wrote the article "Tang Xianzu and syphilis", published in the first issue of "Literature Heritage" in 2000, and later changed its name to "Tang Xianzu suspected of dying of syphilis", but this article was published after the publication. There are not many readers. At the same time, when the collection of his anthology was published, it was edited and deleted, so there are fewer known people.

In the article of Xu, it is not appropriate to argue that Tang Xianzu died of syphilis. That is to say, at best, it can only be regarded as "suspect", but it cannot be confirmed. He is lifting:

Before the death of Tang Xianzu, he said in the small preface of "The Seven Sayings of the World": "The servant is old." Fortunately, two people are big things. It’s impossible to get rid of the disease in the block. Be cautious, still use the linen crown to attack. On the side of the second person, you will see you in the morning. The people are returning to the virtual, and the customs are prosperous. Blame, hate it. For fear, I am forgiven. "With the death of the syphilis, Tu Long, who told his son Yu Heng when he died before his death, was very similar: "I will blame." Its thin and concise, killing the custom, don't yell at me. 』

2 ‧ "Zhang Shizhen" "Yuelutang Collection" Volume 8 "The Sacrifice of the Emperor Lang Linchuan Tang Ruoshi" quoted the teacher's disciple Zhu Eryu as saying: "The disease is caused by ulcers." A general term for tumors or ulcers in ancient times. The latter is a common symptom in the late stage of syphilis patients. 』

3‧Take another "Tang Xianzu has a poem "Seven Years of Sickness and Answers", saying: "If you don't have a disease, you will get a few tons of medicines. You will not be able to get a handful of medicines for a while. The ancient disease is not the same as the new disease." According to "Wild won", Volume 22, "Supervisor and Xu Zhongyu", Zhai Zhongkai is a mountain person in Suzhou, that is, a literati who is a leisurely guest in the government. "The ancient disease is not the same as the new disease," indicating that this is a new disease that has never been found in China. It cannot be effectively treated with traditional ancient methods. This new disease can only be accurately explained by the new syphilis introduced from abroad. 』

4‧ Another year in the year of Tang Xianzu’s examination of the scholar, Wu’s wife died in her hometown. His continued wife, Fu, is a prostitute.

Later, Xia wrote "Tang Xianzu's death test", against Tang Xianzu's death from syphilis, and pointed out that Xu Yufang quoted Tang Xianzu's poem "Seven Years of Diseases and Answers Zhong Zhong", the poem title "Seven Years of Disease" is an allusion from Mencius, not There are seven years of medical history, but "not real". It is also pointed out that Xu Weifang believes that Tang Xianzu’s succession is a prostitute, but it is a misunderstanding of the meaning of the text, because Xu Weifang pointed out in his "Tang Xianzu Chronicle": "The young woman sighs"... Poetry and clouds: 'Dream laughs and wakes up On, the wrong call to send the shadows. In the Ming Dynasty, in the square where Tang Chang’an officials lived, Bai Xing’s “Li Wa Chuan” was equivalent to the Qinglou North, and Fu’s family was also a Chinese. When Xia wrote, he pointed out that the young woman’s surname was wrong. And pointed out: "Determining the young woman's surname, according to what? Determined that this young woman is Tang Xianzu continued to be Mrs. Fu, according to what? The more serious negligence is that the poem of this poem, the apocalypse engraved "The Complete Works of Yuxi Hall" is "Young Women Sigh, Three", and Wan Liben's "Linchuan Tanghai Ruoyu Temple Collection" is "Young Women Sighing Mountains" People, three." Wanli was booked by Tang himself. Please pay attention to the key suggestion of "Showing the Mountain People": Can Tang Xianzu tell some mountain people about his wife's indecent experience and record it? According to this, it can be concluded that the young woman in "Young Women Sigh" has nothing to do with Tang Xianzu's family. Tang Xianzu succeeded with Mrs. Fu’s “Father Fu, Sheng Deshi, and the mother of Beijing”, and was born in innocence; according to Wang Siren, “Shou Tangfu Futai’s wife, 60, 22 rhymes, Mr. Hai Ruo’s succession”, Mrs. Fu’s virtue It can also be circled. 』

He also pointed out that "checking the history of Chinese medicine, ulcer is not only a general term for all kinds of surgical diseases, but also can refer to a kind of head ulcer. It has a long history!" "Said the text": "The ulcer, the head is also created"; "Release the name": "The head has a wound of ulcers." According to "Zuo Chuan? The 19th year of the Gonggong", he was once "born in the head", Shi Jiayu "瘅疽". Hey, the disease is also; hemorrhoids, fever and swollen poison. Referring to the experience of modern doctors in diagnosis and treatment, Tang Xianzu suffers from nothing more than head malignant abscess or tumor. The disease is fierce and the course of illness is short. Not only at that time, even today, it seems to be refractory. 』

When I wrote about Xu Weifang and Xia, the two kings said that Xu Xianfang’s argument about whether Tang Xianzu died of syphilis or not was supported by Xu Weifang. Because I have cited the discussion of the cause of death of Tang Xianzu from the above, in fact, the historical materials cited are not comprehensive, there is a more important historical data, the two kings are ignored, so Xu Weifang’s arguments have to use "doubt" It was sent out, and its essays were very weak, and the sorrow became a deep-spoken ancestor of the ancestor of the ancestors, and Mr. Xia Shi was stunned by the adoration of the idol Tang Xianzu.

In the late Ming Dynasty, Xu Shuzhen’s "Living Buried Xiaoxue ‧ Volume IV" has a record: "If the article of the scholars is not too much in my dynasty, it is a legend, and it is amazing. "Peony Pavilion" is especially Hey. In the text of the old age, Han Qimei: If Russell hates Taicang, the death of this legendary Du Li Niang is even more so, with the condition of Yangzizi, and the Pingzhang is also shadowy. According to the Xiangyang Immortal, Wang Yuanmei made a biography for him, and he also showed his glory. Later, the Taicang people were even more dissidents: after the reincarnation of Fuyang, they were married to the Hui women, and they said that they were ignorant, and if they were true. However, when I heard that if the sergeant died, he would do everything in his hand. If he was not slandered by a proverb, then he should also be ridiculed. However, it is even more sensible if the scholar has this romanticism, and the room has no sputum, and the wife is old and old, it seems that it is not appropriate to get this bad news, set to ridicule the real ear. 』I have mentioned: "When you hear the death of a man, you will do your best." 』

According to the feudal literati from the last century under the worship of Tang Xianzu, there is also a mention of this predecessor's record, all of which are the words of the singer who deliberately slandered Tang Xianzu. However, most of the literati who lived in the late Ming Dynasty were Tang Xianzu fans. Xu Shuzheng was full of praise for Tang Xianzu, not a slander. On the contrary, in this record, he mentioned that he was listening to the literati’s personal confession (“early smell”), which was recorded in the end of the Ming Dynasty. It was rumored that Tang Xianzu died of Hualiu’s disease instead of him. Defamation. According to this record, I also know that it is not Xu Yifang's deliberate nonsense for the later generations, but that people in the Tang Xianzu era knew this. When they died, they were "hands and feet" (the joints of long syphilis are like broken hands and feet). To say that strict defamation is to go to the Qing Dynasty to learn the glory of the road, and some meteorological, such as the Qianlong era Gu Gongyu's "Summer Record": "There were people who traveled to the Hades, see the A-Prison, and the two People, very bitter. Who is it for? Ghosts and paws: This is the yang masterpiece of "The Return of the Soul" and "The West Chamber", never surpassing. Yi Yi. 』

Therefore, in the Ming Dynasty, Xu Shuzhen’s text, when he wrote Tang Xianzu’s death, was “hands and feet”. This is the same as Xu Weifang’s poem when he cites Tang Xianzu’s discussion about Tu Long’s death from syphilis. The ulcers, the bones and bones are bad, the pain can not be tolerated, and the teaching order is a little bit fixed. In the "Ten Tens of the Game", when Tu Long, who was suffering from syphilis, died, "the bones are broken" is synonymous. The so-called "when the singer dies, the hand and the foot do their best" is also the same as "when Ruoshi died, the bones and muscles are bad." This is the rumor that Tang Xianzu’s contemporaries in the late Ming Dynasty later appeared in the late Ming Dynasty. It was written on the same day’s notes, not the “doubt” of the later generations of Xu Weifang. However, if Mr. Xu has a more extensive historical data and a record of the people at the end of the Ming Dynasty, it is more convincing for Xu Weifang’s argument that Tang Xianzu’s syphilis has died, and that Tang’s ancestors will not be treated as religious. Mr. Xia wrote the text for the poor. (Liu Youheng: "A Study of the Truth of Ancient Drama History", Taipei: City State Press, 2019)

1 note

·

View note

Text

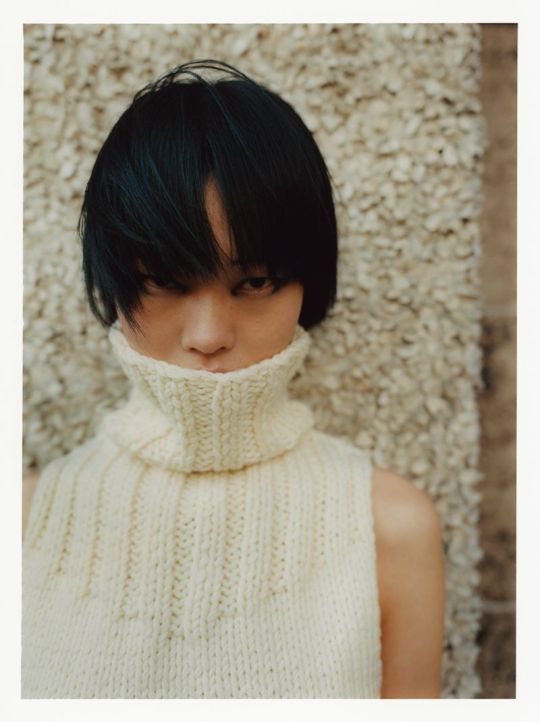

Xiaoxue Tang by Agnieszka Kulesza & Łukasz Pik for WRPD Magazine April 2023

100 notes

·

View notes