#Stephen Goosson

Text

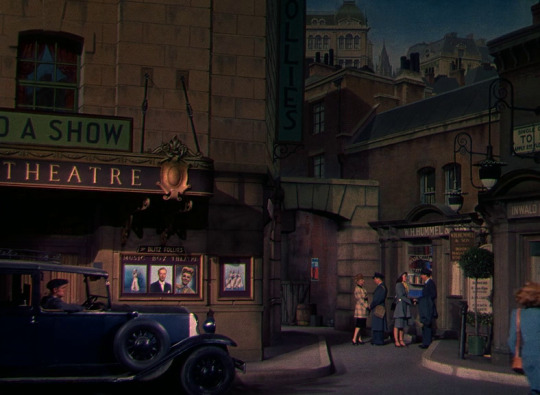

Tonight and Every Night (Victor Saville.1945) | Art direction by Lionel Banks, Stephen Goosson and Rudolph Sternad

1 note

·

View note

Photo

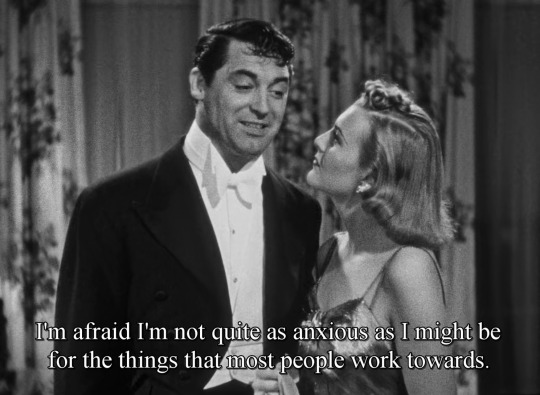

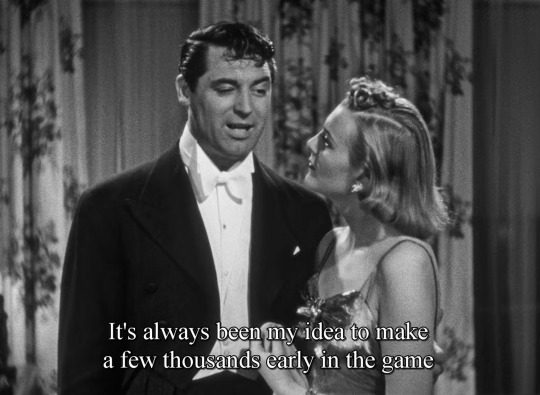

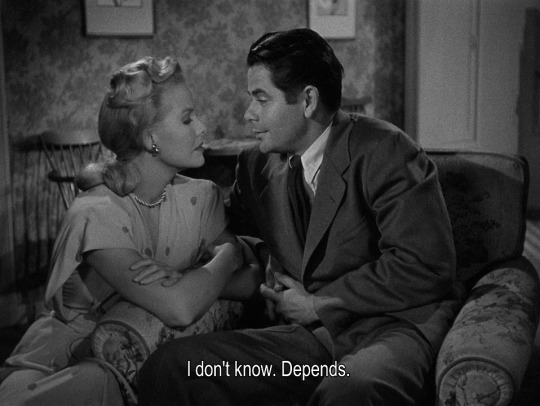

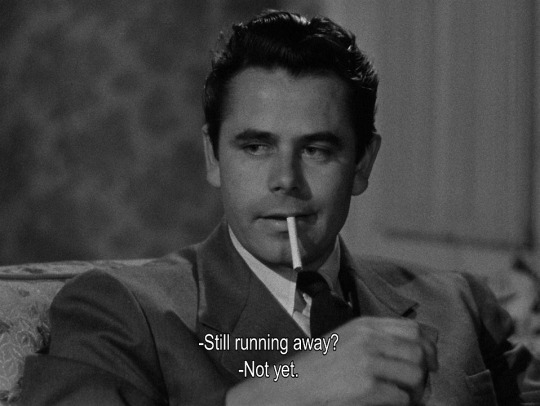

Cary Grant, Doris Nolan, and Henry Kolker in Holiday (George Cukor, 1938)

Cast: Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Doris Nolan, Lew Ayres, Edward Everett Horton, Jean Dixon, Henry Kolker, Henry Daniell, Binnie Barnes. Screenplay: Donald Ogden Stewart, Sidney Buchman, based on a play by Philip Barry. Cinematography: Franz Planer. Art direction: Stephen Goosson. Film editing: Al Clark, Otto Meyer. Music: Sidney Cutner.

Of the four films Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn made together, I think George Cukor's Holiday may be my favorite. Their first, Sylvia Scarlett (Cukor, 1935), is just, well, weird. The Philadelphia Story (Cukor, 1940) has maybe a touch too much MGM gloss for my tastes, and James Stewart has a better role than Grant does. Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938) is a greater movie than Holiday and one of the funniest films ever made, but as a showcase for the talents and the chemistry of Grant and Hepburn it falls short because they're mostly called on for one note: zaniness. But Holiday allows them to show off almost everything they could do. It allows Grant to be suave and ardent and acrobatic and sexy. It lets Hepburn be intense and vulnerable and glamorous and noble. As films like his David Copperfield (1935) and The Women (1939) show, Cukor was a master at directing ensembles of colorful players. Here he directs the usually bland Lew Ayres in a heartbreaking performance as Ned Seton, the trapped, alcoholic younger brother of Linda and Julia. He makes Doris Nolan's Julia first a credible match for Grant's Johnny Case and then eases her transition into a chip off the old ice block: the die-hard capitalist tycoon paterfamilias played by Henry Kolker. Johnny's background is illuminated by his friendship with the witty, professorial Potters (Edward Everett Horton and Jean Dixon) as that of the Setons is by the snide, snobbish Crams (Henry Daniell and Binnie Barnes). Of course, all of these relationships are built into the film by its source, a play by Philip Barry adapted by Donald Ogden Stewart and Sidney Buchman, but it's Cukor's skill at keeping them in balance that allows the film to stay away from sentimentality or getting bogged down in satire of the rich. There's a bit of the latter -- and of the leftist views that would later get Stewart blacklisted -- when Seton calls Johnny's desire to take time off from making money "un-American," to which Linda replies, "Well, then, he is, and he won't go to heaven when he dies, because apparently he can't believe that a life devoted to piling up money is all it's cracked up to be." Holiday has a little more satiric bite than the other Barry-Stewart-Cukor-Grant-Hepburn collaboration, The Philadelphia Story, but this is Depression-era political commentary with a light touch. Holiday is one of the greatest members of a much-abused genre, the romantic comedy.

images from 365filmsbyauroranocte

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sci-Fi Saturday: Just Imagine

Week 6:

Film(s): Just Imagine (Dir. David Butler, 1930, USA)

Viewing Format: YouTube

Date Watched: June 19, 2021

Rationale for Inclusion:

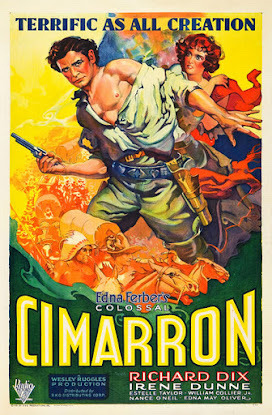

In looking into science fiction films of the 1930s, the first one I ran across that was new to me was also the first of its genre to receive an Academy Award nomination, Just Imagine (Dir. David Butler, 1930, USA). Not surprisingly if you're up on your Oscar history, this nomination came in an aesthetic category: Art Direction. Subsequently, designers Stephen Goosson and Ralph Hammeras lost to Max Rée for the Western Cimarron (Dir. Wesley Ruggles, 1931, USA).

Other than being a piece of Academy Award trivia, including Just Imagine in our survey made sense because it was intermixed with genres we had not seen combined with sci-fi yet: comedy and the musical. The former was rarely seen combined with science fiction in the silent era, and the latter required the innovation of synchronized sound motion pictures.

Just Imagine is the first talking picture we watched, but it was not the first sound science fiction film produced. That distinction seems to belong to the 1929 adaptation of Jules Verne's The Mysterious Island (Dir. Lucien Hubbard, USA), which was produced as a silent film with a sound sequence and synchronized music track later added. I do not recall why we opted to skip this film in our survey: whether it was an issue of outright missing its existence and availability on DVD or through Archive.org, or intentionally skipping it because we had recently watched 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Dir. Stuart Patton, 1916, USA), which included narrative elements adapted from that novel.

At any rate, for its cross-genre whimsy and Oscar nomination, I decided Just Imagine needed to be included on our survey despite viewing access being inconvenient. Despite its historic status, no mainstream media or art house distribution service has made the film available on physical media or streaming. Various DVD-R versions circulate, and it can be found in unofficial versions on YouTube (as we watched it) or Archive.org.

Reactions:

The lack of mainstream release for Just Imagine makes sense for two reasons: due to copyright issues and only being of relative niche interest, late 1920s and early 1930s films aren't as widely available on contemporary home formats in general, and the film overall is not very good.

The main weaknesses of Just Imagine come down to its plot being a weak, rote triangulated romance, mediocre songs, and emphasis on Elmer "El" Brendel's comedy. Unlike his vaudevillian and cinematic contemporaries the Marx Brothers, Brendel's Swedish immigrant archetype has not retained his appeal or cultural relevance with later generations. However, his character's fish out of water immigrant schtick works well within the character's Rip Van Winkle inspired subplot.

The Academy wasn't wrong in nominating Just Imagine for its art direction though. The futuristic art deco city of 1980 is beautiful looking, and clearly indebted to the aesthetics of Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lang, 1927, Germany), including video phones and personal airplanes instead of automobiles traveling between skyscrapers. The laboratory equipment that brings the fifty years dead Single O (Brendel) back to life was apparently too expensive a build for just one use because it was reused to more iconic effect the following year in Frankenstein (Dir. James Whale, 1931, USA).

Single O's man from present day in the future storyline would be repeated in later sci-fi works, like the serial Buck Rogers (Dir. Ford Beebe and Saul A. Goodkind, 1939, USA), movie Judge Dredd (Dir. Danny Cannon, 1995, USA), and television series Futurama (1999-2003, USA). Other genre tropes that come into play throughout the film include food in pill form, people receiving number designations, marriages being bureaucratically arranged, reproduction without the sex or body horror, and a trip to a Mars populated by Martians. None of these aspects originate with Just Imagine, just cement its genre status.

For sci-fi fans, the set pieces and tropes in play make Just Imagine worth watching at least once, if only to appreciate later, better iterations of its elements. For classic film and pre-code cinema fans, it's an interesting cultural artifact for no other reason but its cast featuring Brendel, Maureen O'Sullivan, and Joyzelle, she of the infamous "naked moon dance" in The Sign of the Cross (Dir. Cecil B. DeMille, 1932, USA).

1 note

·

View note

Photo

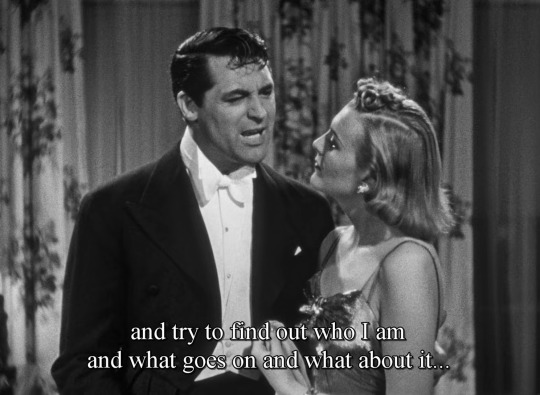

The Lady from Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1947).

#the lady from shanghai#the lady from shanghai (1947)#orson welles#rita hayworth#charles lawton jr.#rudolph maté#joseph walker#viola lawrence#sturges carne#stephen goosson#wilbur menefee#herman n. schoenbrun#jean louis

241 notes

·

View notes

Photo

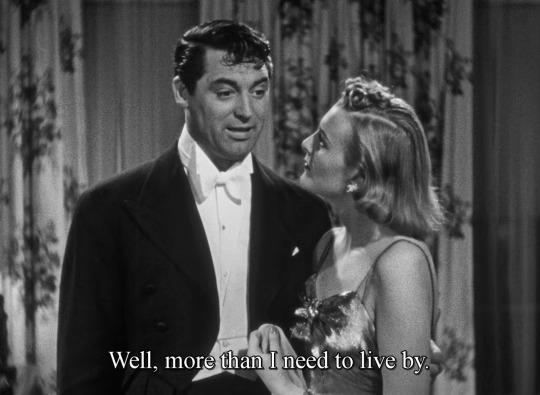

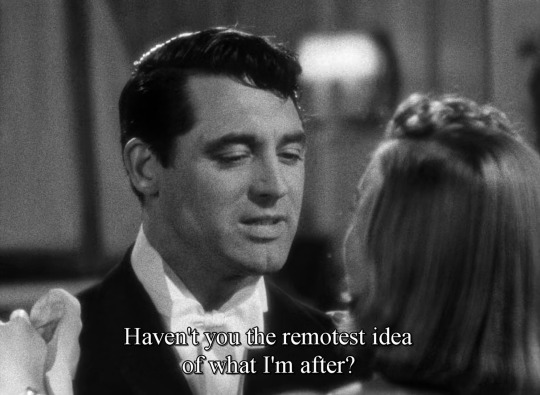

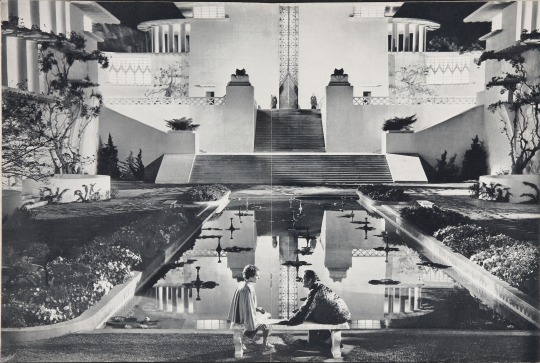

Ronald Colman in a still from the drama-fantasy film Lost Horizon (USA, 1937, dir. Frank Capra) | Columbia Pictures

For his lavish sets for Lost Horizon, set designer and art director Stephen Goosson won the Academy Award for Best Art Direction at the 10th Academy Awards (1938). Gene Havlick and Gene Milford won the Academy Award for Best Film Editing for their work on the movie.

#Ronald Colman#1937#actor#film#Lost Horizon#film still#Frank Capra#Columbia Pictures#set design#art direction#Stephen Goosson#Oscars#Best Art Direction Oscar#Gene Havlick#Gene Milford#Best Film Editing Oscar#10th Academy Awards#February Oscar month#Academy Awards#stairs#escaliers#art deco

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lost Horizon (1937)

Asia and Europe were about to plunge into warfare when Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon was released in American theaters. The Chinese, mired in civil war between the Communist Party and the nationalist Kuomintang, were about to find a common enemy in the Japanese. Meanwhile, Nazi Germany continued its saber-rattling, leaving other European states looking nervously towards the continent’s increasingly militarized center. At this time, Americans, still reeling from the Depression and not yet too concerned about enforcing Wilsonian human rights elsewhere, longed for escape, for being sheltered from the news and conflict and suffering. A utopia, a Shangri-La, must have seemed appealing. The Shangri-La depicted in Lost Horizon – based on James Hilton’s 1933 novel of the same name – might fit the bill, without closer inspection.

It is 1935 and soon-to-be Foreign Secretary Robert Conway (the reliable Ronald Colman, performing solidly in this outing) is a diplomat working to evacuate as many white people as he can from a city under attack from Mao’s Communists. The Chinese heathen can fend for themselves, I guess. Among those climbing aboard the diplomatic plane to Shanghai are Conway’s younger brother George (John Howard), paleontologist Alexander Lovett (Edward Everett Horton), criminal Henry Barnard (Thomas Mitchell), and the terminally ill Gloria Stone (Isabel Jewell). Their plane has been hijacked and crash lands somewhere in the Himalayas. A Shangri-La native, Chang (H.B. Warner; one of many white actors playing an Asian character), rescues the British subjects and leads them to his home, a lush valley where the residents age much slower and are shielded from the brutal Tibetan weather. There, George is enchanted by a lady named Maria (Margo) and Gloria’s ailments have disappeared. Conway also meets the High Lama (Sam Jaffe), who eventually reveals that their arrival in Shangri-La has not been by chance. When the British characters raise questions about contacting the outside world, their questions are left unanswered.

With an original runtime of six hours, then trimmed to three-and-a-half hours, and finally settled for a runtime of just over two hours (today, the film is considered partially lost, but more on that later), Lost Horizon’s screenplay – penned by Capra regular Robert Riskin (1934′s It Happened One Night, 1941′s Meet John Doe) – appears to be an amalgam of ideas, tossed like a salad, that combine into an unfocused end product. The notion of Shangri-La and its inhabitants is proclaimed to be universalist, for the bounty of all those looking to coexist with others. But Riskin’s adaptation of Hilton’s novel adheres to Hilton’s conception that Shangri-La was once inhabited by native Tibetans, and that those Tibetan leaders were replaced by European wanderers who introduced Western knowledge for themselves, not for the Tibetans who could no longer attain an elite status. A “Christian ethic” where, “the meek shall inherit the Earth” is considered superior to other structures of social organization, according to the High Lama (as sociology, that’s just lazy writing). Riskin makes little attempt to either critique the existing organization of Shangri-La nor does he – outside of one lengthy soliloquy by the High Lama – use the shining example of Shangri-La to effectively juxtapose life in the Himalayas with life in places soon to be reduced to charred, damaged battlefields. However, as a fantasy film, Lost Horizon wonderfully constructs the awesome settings described in the Hilton novel.

Though few in 1937 criticized Lost Horizon for its Atlanticist imperialism upon release, those features are more apparent eighty years later. Considered a masterwork from Frank Capra, the film has aged poorly on how it treats the Asian setting and individuals that it depicts. Though the High Lama and Chang mention the diversity of Shangri-La, we only see white actors in yellowface playing the leaders as the actors of Asian descent play the speechless grunts patrolling the settlement. The High Lama’s functions are an embodiment of the perceived religious, cultural, and technological superiority of the West combined with an awkward mysticism that stems from exotic places. The backwardness of any Asian characters reduces them to grinning, violent caricatures.

Yet where Lost Horizon succeeds as a film – though despicable in its racialized writing and portrayals – is in its technical components. Cinematographers Joseph Walker and Elmer Dyer are allowed immense backgrounds to work with, allowing for an incredible scope to the production not often seen after the free-spending epics in the later silent era. Editors Gene Havlick and Gene Milford play with the film’s practical visual effects in groundbreaking fashion for the time. Some of their visual tricks, borrowing heavily from the later silent era, make any miniatures or matte paintings that appear to seem realistic. With a then-astronomical budget of $2 million (~$34 million in 2017′s USD), Capra lavished much of that money from Columbia Pictures – in 1937, Columbia was not quite a major studio on the level of Warner Bros. or Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) yet – on the production design by Stephen Goosson. Goosson and his staff built sixty-five sets, constructing the walls and buildings of Shangri-La at Columbia’s ranch in Burbank. Extensive research also produced replications of upwards of 700 props used in Tibetan life. This expansive collaboration of cinematographers, editors, and production designers help Lost Horizon to transcend its Orientalist trappings, its troubled writing, if only to a limited extent.

Lost Horizon presented a breakthrough for composer Dimitri Tiomkin, who would become Frank Capra’s favored composer through You Can’t Take It with You (1938), into Capra’s Why We Fight WWII propaganda series, and until It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Over this next decade, Tiomkin’s concentration on piano and European classical music expanded to grand orchestral works with American influences thanks to his friendship with Capra. But for this first score for a Capra film, the strings dominate the faux Eastern-sounding melodies – there is a long history of European composers trying to imagine Asia through their music. Although in too many places (especially in the opening half of Lost Horizon), Tiomkin’s brass is too harsh where he should be more delicate with his passages. Yet there are gorgeous cues contained within Tiomkin’s composition, most notably during the swimming sequence and the resolving sequences of the film – this includes the funeral procession (perhaps the most memorable cue of the score, thanks to a wordless choir) and an attempted flight from Shangri-La. This is one of Tiomkin’s greatest works, with a curious orchestration and thematic development that would be recalled for his work in Land of the Pharaohs (1955).

Existing prints of Lost Horizon are partially lost. The print that I saw for this write-up was on Turner Classic Movies (TCM) and is the most complete edition available. This print is the one recommended for those interested in seeing Lost Horizon – the 1986 restoration by the American Film Institute (AFI) and the UCLA Film and Television Archive which runs 132 minutes and contains 125 minutes of footage. The seven missing minutes are accompanied by the film’s soundtrack (which thankfully exists in its entirety), but includes still images of the missing scenes. Do not watch any other prints other than the AFI/UCLA version – exceptions can be made, of course, if you stumble upon the original six hour print only shown to Columbia executives.

For Columbia’s co-founder and president Harry Cohn, Capra’s indiscretions of shooting excessive takes and ballooning production costs damaged his relationship with Capra. Unhappy with preview footage screened in January 1937, Cohn – believing that audiences would not be patient enough with a lengthy feature film despite the fact that some silent films ran over three hours or longer (1916′s Intolerance is 210 minutes; 1923′s La Roue is 273 minutes) – eventually seized Capra’s film from him and cut Lost Horizon down to the familiar 132 minutes seen in its roadshow format. Decades later, Capra still would not forgive Cohn for how he treated the final cut of Lost Horizon.

Confounded by too much exposition and an outdated portrayal of its Asian characters and cultures, Lost Horizon – like fellow 1937 release The Good Earth (a better movie with a more sensitive take on Asian characters, despite the rampant yellowface) – has the imagination of its artisans and craftspersons to make it one of the grandest Hollywood productions of the 1930s. The eleventh-highest grossing film at the American box office in 1937, Lost Horizon provided a temporary utopia for Depression-era audiences yearning for such an escape. The Library of Congress’ National Film Registry - a collection of American films regarded as national treasures, and marked for preservation - recognized this, inducting Capra’s film into the Registry just last year. For some characters in Lost Horizon, Shangri-La is paradise found. For others, a prison. Modern audiences might scoff without much thought when considering the elements that constitute Shangri-La. But for a certain people in a different time, whatever troubled Shangri-La probably was more easily forgiven.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Lost Horizon#Frank Capra#Ronald Colman#Jane Wyatt#Sam Jaffe#John Howard#H.B. Warner#Edward Everett Horton#Thomas Mitchell#Isabel Jewell#Margo#Robert Riskin#Joseph Walker#Elmer Dyer#Gene Havlick#Gene Milford#Stephen Goosson#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

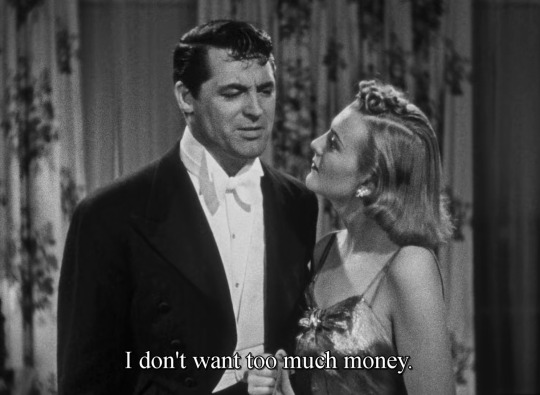

The Lady From Shanghai (1947)

Today's review on MyOldAddiction.com, The Lady From Shanghai by #OrsonWelles starring #RitaHayworth, "features some of the most beautifully shot scenes of the decade"

ORSON WELLES

Bil’s rating (out of 5): BBB.5.

USA, 1947. Mercury Productions. Screenplay by Orson Welles, based on the novel If I Die Before I Wake by Sherwood King. Cinematography by Charles Lawton Jr.. Produced by Orson Welles. Music by Heinz Roemheld. Production Design by Sturges Carne, Stephen Goosson. Costume Design by Jean Louis. Film Editing by Viola Lawrence.

[youtube=https://www.…

View On WordPress

#Carl Frank#Charles Lawton Jr.#Erskine Sanford#Evelyn Ellis#Everett Sloane#Glenn Anders#Gus Schilling#Harry Shannon#Heinz Roemheld#Jean Louis#Louis Merrill#Mercury Productions#Orson Welles#Rita Hayworth#Sherwood King#Stephen Goosson#Sturges Carne#Ted de Corsia#Viola Lawrence

0 notes

Text

Tuesday, November 10, 1931|Honoring movies released from August 1, 1930 - July 31, 1931

OUTSTANDING PRODUCTION

youtube

WINNER

CIMARRON

RKO Radio

NOMINEES

EAST LYNNE

Fox

THE FRONT PAGE

The Caddo Company

SKIPPY

Paramount Publix

TRADER HORN

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

DIRECTING

youtube

WINNER

SKIPPY

Norman Taurog

NOMINEES

CIMARRON

Wesley Ruggles

A FREE SOUL

Clarence Brown

THE FRONT PAGE

Lewis Milestone

MOROCCO

Josef Von Sternberg

CINEMATOGRAPHY

youtube

WINNER

TABU

Floyd Crosby

NOMINEES

CIMARRON

Edward Cronjager

MOROCCO

Lee Garmes

THE RIGHT TO LOVE

Charles Lang

SVENGALI

Barney "Chick" McGill

ACTOR

WINNER

LIONEL BARRYMORE

A Free Soul

NOMINEES

JACKIE COOPER

Skippy

RICHARD DIX

Cimarron

FREDRIC MARCH

The Royal Family of Broadway

ADOLPHE MENJOU

The Front Page

ACTRESS

WINNER

MARIE DRESSLER

Min and Bill

NOMINEES

MARLENE DIETRICH

Morocco

IRENE DUNNE

Cimarron

ANN HARDING

Holiday

NORMA SHEARER

A Free Soul

ART DIRECTION

WINNER

CIMARRON

Cimarron

NOMINEES

JUST IMAGINE

Stephen Goosson, Ralph Hammeras

MOROCCO

Hans Dreier

SVENGALI

Anton Grot

WHOOPEE!

Richard Day

WRITING (ORIGINAL STORY)

WINNER

THE DAWN PATROL

John Monk Saunders

NOMINEES

THE DOORWAY TO HELL

Rowland Brown

LAUGHTER

Harry d'Abbadie d'Arrast, Douglas Doty, Donald Ogden Stewart

THE PUBLIC ENEMY

John Bright, Kubec Glasmon

SMART MONEY

Lucien Hubbard, Joseph Jackson

WRITING (ADAPTATION)

WINNER

CIMARRON

Howard Estabrook

NOMINEES

THE CRIMINAL CODE

Seton I. Miller, Fred Niblo, Jr.

HOLIDAY

Horace Jackson

LITTLE CAESAR

Francis Faragoh, Robert N. Lee

SKIPPY

Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Sam Mintz

0 notes

Photo

Settling in with #BorisKarloff and #knitting. Monday begins the B term for @asuonline so I'm relaxing with my favorite Karloff. I mean look at that magnificent chair, the art direction by Stephen Goosson is outstanding https://www.instagram.com/p/B9xnpVKJL6n/?igshid=18pdxgfwvgjex

0 notes

Photo

Film set: 'Lost Horizon'. Stephen Goosson. 1937. #duille #duilledesign #art #design #architecture #artnouveau #artdeco #artsandcrafts #modernism #charlesrenniemackintosh #scotland #scottish #celtic #northampton #england #madeinbritain #jewellery — view on Instagram http://ift.tt/2DVceCP

0 notes

Text

Dead Reckoning (John Cromwell, 1947) | Art direction by Stephen Goosson and Rudolph Sternad

#noir architecture#columbia pictures design#architecture of John Cromwell#Stephen Goosson#Rudolph Sternad

1 note

·

View note

Text

Walter Brennan, Gary Cooper, Irving Bacon, Barbara Stanwyck, and James Gleason in Meet John Doe (Frank Capra, 1941)

Cast: Gary Cooper, Barbara Stanwyck, Edward Arnold, Walter Brennan, Spring Byington, James Gleason, Gene Lockhart, Rod LaRocque, Irving Bacon, Regis Toomey. Screenplay: Robert Riskin, based on a story by Richard Connell and Robert Presnell Sr. Cinematography: George Barnes. Art direction: Stephen Goosson. Film editing: Daniel Mandell. Music: Dimitri Tiomkin.

Meet John Doe opens with reporters and editors at a newspaper being fired because the owner wants it to be, as the paper's new slogan says, "streamlined ... for a streamlined age." And the plot involves a very wealthy man who uses a phony populist approach to try to get himself elected president. Who says an 82-year-old movie isn't relevant today? But the movie eventually falls apart because Frank Capra can't get his story to make sense. I never watch a Capra film without wanting to throw something at the screen, and that includes the beloved It's a Wonderful Life (1946), which makes me faintly nauseated. Meet John Doe has a few wonderful things going for it, principally the opportunity to see Barbara Stanwyck and Gary Cooper at their starry prime. (Though they were much better in a movie they made together in the same year, Howard Hawks's Ball of Fire.) Experience tells, and by 1941 Stanwyck had been making movies for more than a decade, and Cooper had been in films since the mid-1920s. They had the kind of easy, spontaneous, natural manner on screen that could steady even the most wobbly vehicle. Meet John Doe starts to wobble about halfway through, when it becomes apparent that there is no easy way Capra and screenwriter Robert Riskin can handle the director's muddled populist sentiments: Capra always wants to celebrate the "common man" in his movies, but it was clear to anyone on the brink of the entry of the United States into World War II that the common man was a dangerous force to work with. So what we have in the film is an odd mix of sentimentality and cynicism. Stanwyck's character, Ann Mitchell, starts as a cynic, concocting a sob story about a "John Doe" who threatens to commit suicide because he's fed up with a corrupt society. She does it to save her job at the newspaper, and the equally cynical managing editor Henry Connell (James Gleason) decides to run with it. That's when they find a homeless man (Cooper) to pretend to be the real John Doe. When he turns out to be an inspiration to the "common man" of Capra's fantasies, bringing about peace and harmony across the land, the sentimentality takes over, converting Ann and Connell, but also playing into the hands of the paper's owner, D.B. Norton (Edward Arnold) , who tries to use John Doe's followers for political gain. And when John Doe is exposed as a fake, the adoring millions suddenly turn into a raging mob. If Capra weren't so invested in making things turn out all right, he could have created a powerful satire, but he couldn't find an ending to the film that would satisfy both his Hollywood-nurtured sentimentality and the logic of the plot.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lost Horizon (Dir. Frank Capra, Set Design: Stephen Goosson, 1937).

Source

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Framed (Richard Wallace, 1947).

#paula (1947)#framed (1947)#richard wallace#glenn ford#janis carter#burnett guffey#richard fantl#carl anderson#stephen goosson#jean louis#fay babcock#sidney clifford#wilbur menefee#ben maddow#john patrick

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jane Wyatt and Ronald Colman in a still from the drama-fantasy film Lost Horizon (USA, 1937, dir. Frank Capra) | Columbia Pictures

For his lavish sets for Lost Horizon, set designer and art director Stephen Goosson won the Academy Award for Best Art Direction at the 10th Academy Awards (1938). Gene Havlick and Gene Milford won the Academy Award for Best Film Editing for their work on the movie.

#Jane Wyatt#1937#Ronald Colman#Lost Horizon#film#Academy Awards#Oscar#10th Academy Awards#Stephen Goosson#Best Art Direction Oscar#Frank Capra#Gene Havlick#Gene Milford#Best Film Editing Oscar#February Oscar month#set design#art direction#art deco#film still

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Over 21 (Charles Vidor, 1945) | Art direction by Stephen Goosson and Rudolph Sternad

0 notes