#Sometimes it's a way of emphasising the sense of confinement and risk

Text

Appreciation post for the Hephaestus crew using the word 'boat' to refer to spaceships

Ep9 The Empty Man Cometh

EIFFEL: Unfortunately the good folks at Goddard Futuristics spared every expense when they put together this boat. [referring to the Hephaestus]

Ep23 No Pressure

EIFFEL: The power and the support systems on this boat do kinda have a rocky relationship… [referring to Lovelace's shuttle]

Ep27 Knock, Knock

MINKOWSKI: I don't trust anyone on this boat right now. [referring to the Hephaestus]

Ep29 Pan-Pan

LOVELACE: Believe me, kids, right now I'm up for killing everything and everyone on this boat. But I promise the grid is down. [referring to the Hephaestus]

Ep30 Mayday

EIFFEL: Eiffel's Action Plan #1: turn this boat around, get back to the Hephaestus. [referring to Lovelace's shuttle]

Ep42 Time to Kill

EIFFEL: And we're sure our little lifeboat can survive the three hour tour? [referring to the experimental module]

Ep61 Brave New World

MINKOWSKI: Miss Young, you're going to go up to the bridge, you're going to get me flight capabilities, and then you and Kepler are going to get the hell off my boat. [referring to the Sol]

#Pretty sure this is all of the uses of 'boat' to actually refer to a spaceship or space station#There's something in the fact that it's only the protagonists who do this#Yes it's partly that we spend more time with them and hear more of their quips#but also there's something about the attitude it reflects towards these high tech (if run down) spacecraft#'Yes we're 8 lightyears from Earth but this is basically a fucked up boat'#They use this phrasing in moments of anger and frustration#Sometimes it's a way of disparaging the station/ship#Sometimes it's a way of asserting ownership over it#Sometimes it's a way of emphasising the sense of confinement and risk#They are sailors trapped together on a boat among the stars at the mercy of the storm…#Also it fits with the retro-futuristic vibe of the Hephaestus#It's a space station but spiritually it's a boat with a patchwork of repairs that's just sprung another leak#I do kinda want to give a honorary mention to Hera's 'speaking as the ship we're going down'#because that's also a nautical way of talking about the Hephaestus#and also because I feel bad when I write a 'Hephaestus Crew' post that doesn't include her#wolf 359#w359#doug eiffel#renee minkowski#isabel lovelace#the empty man posteth

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

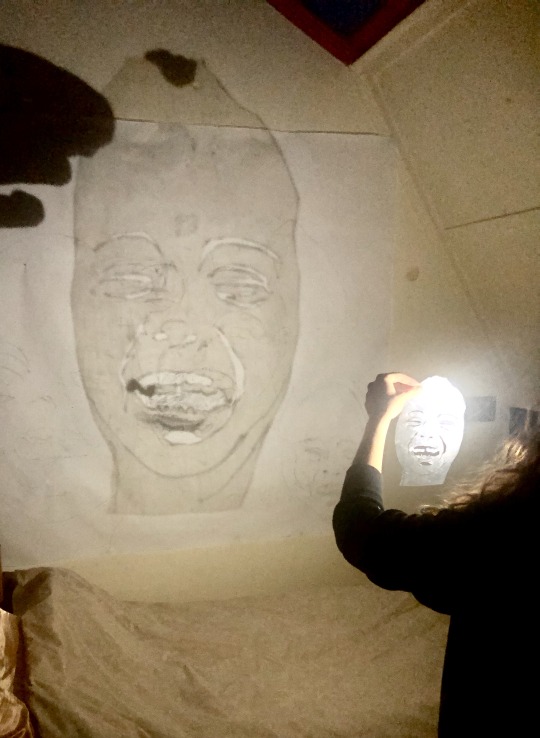

It’s raining and I ran in the rain and now I’m cosy and grateful to be writing about strange threads of things that I care about. Last night I turned off the lights in my bedroom and shone a phone torch through the stencil for the mask of my face, and made big grinning shadows above my bed. Layering them up. Again -- terrifying. I drew around the shape of the shadow, and added to the blur of the ones beneath it.

Continuing this round-about exploration of masks and shadows, I’ve been wanting to draw together more of the points in the article that I’m reading by Wendy Doniger -- Self-Impersonation in World Literature (2004). Reading this has been a bit of an ecstatic experience. A shining pinnacle example of academic writing that is both very dense and very light -- a generous, all-encompassing, highly controlled blurring of disciplines and areas of research. Drawing upon whatever it is that accurately produces & communicates the thread of ideas -- as opposed to remaining confined within a designated ‘discipline’ or academic-jargon rulebook out the perceived need to uphold a singular, acceptable mode of knowledge-production? Something like that. Whatever it is, I am loving what I’m reading, and I don’t want to forget it. And so I’m paraphrasing (or directly quoting) some of her key points below:

In all of our acts, masks and self-impersonations, we can never truly escape ourselves: “ The hope of getting away from oneself is always doomed to failure...when we have a chance to pretend, to become someone else, we will still end up as the same selves we were, reinventing the same wheel -- the wheel that is the metaphor that Hindus and Buddhists use for the process of reincarnation, the cycle of Samsara”

If we cannot, in fact, ever ‘escape ourselves’, the understanding of this doesn't need to be coloured by an imagined fatalism or helpless inability to change: Wendy Doniger offers up 5 ‘good news’ variants on this myth of self-imitation, which I will paraphrase below:

1. We are all already many people: Within the landscape of our experience of being ‘a self,’ there are many many options to turn to. “We are indeed imprisoned in our ‘self’, but it is a very big prison. When we put on a mask, we have a choice of a thousand faces, and in a very real sense, they are all our own.”

2. The mask may prove to be more ‘real’ than the imagined face beneath: Doniger proposes the idea that the true mystery of the world is in fact the in visible -- daring to engage with the surface-level, the known -- not the invisible. “Things are the way they seem, only more so.” I am not entirely sure if I understand this. But I believe it brings us back to the idea that ‘here, there is nothing to find -- but that is the finding’. We remain unable to see things as they really are, due to the distracting idea that there is something more real underneath the view that you already have? Perhaps it is all already here.

3. Sometimes the mask turns out to be the same as the face all along: “A mask must reveal the face concealed by the face of the mask.” Doniger references practices of method-acting, where the performer draws entirely on the narrative their own life, in order arrive in someone else’s. She also speaks of a Balinese dancer, who says that when dancing with a mask, your face must be the same as the mask -- the mask is perhaps just a bigger, emphasised mirror; a vehicle through which your own face (and no-one else’s) can be returned to, and channelled. Going away in order to come back?

4. If the default face is already a mask, then the mask may be used as a safe-house for the ‘true self’-- paradoxically coaxing it out: The ‘transformation of identity through disguise’ in the context of masks and masquerades -- literally and metaphorically -- is well known. The mask is not so much about what it ‘masks’, but about what it enables -- the transformation it brings about. You can say anything with a mask on. In disguise, saying whatever you want, there is less perceived risk of ‘giving yourself away’. And so, of course, you do arrive, you do give yourself away. Doniger observes this double bind we find ourselves in, in which ‘we wear a mask to attract the one person who can love us without a mask’.

5. The potential to be transformed by the wearing of the mask: You do not ‘become’ the mask, but are changed / revealed / extended by wearing it. Doniger asks, “if the mask has the capacity to reveal unconscious truths, then does ‘taking off’ the mask mean moving further from the truth?”. There is no final answer. Sometimes in concealing, we reveal. Sometimes the ‘lie’ is more true that the ‘truth’ -- revealing unconscious truths. Sometimes the mask is not a mask at all if you can bring yourself to really look at it. Sometimes the shadow of the mask on the shape of the face is what allows the face to be defined most clearly.

It would appear that the main good news is that even within this circular allegory of self-impersonation upon self-impersonation, there remains the potential for some kind of transformation. To catch yourself by surprise -- even if it is just the surprise of looking behind the mirror and finding that no-one else is really there.

Doniger concludes:

“Since every lie covers up a truth, a series of masks passes through a series of lies and truths; perhaps, then, the best bet is to wear as many as possible, and realise you are wearing them, and try to find out what each one reveals and conceals. If you just stand there with your unconscious mask on your face, you never learn anything about the selves”.

1 note

·

View note

Text

san andreas fault

The first thing worth saying about The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner is that although it is set in a prison for women, it is really nothing like Orange is the New Black. It is also not exactly a ‘prison novel’. Perhaps any description of it ought not to be centred on a prison at all; if we call it instead ‘a novel about a woman who had a rough childhood, who becomes a sex worker and whose life takes a bad turn through circumstances beyond her control’, that would be another way of talking about it. But it could also be called a ‘a novel about the post-industrial American landscape’ or ‘a novel about how capitalist ideology came to occupy unquestioned every aspect of what had previously been the prerogative of the state’. There’s a lot going on here.

Most of the chapters follow a woman named Romy Halls. Hers is one of those names which seems at first almost too Dickensian to be real, but which somehow concedes its own sort of authenticity. Romy is sent to jail after killing a man; after they met in the strip club where she was a dancer, this man began stalking her. Owing to an ineffectual public defender, this was no defence at all in the eyes of the judge. Romy is sent down, separated from her young son, with little hope that she will ever see him again.

Prison is relentlessly awful. Every pointless, inhumane, degrading, exploitative detail is noted by the author — everything from the arbitrary rules that determine what can be worn to the expensive bureaucratic monopoly of the prison telephone system. OITNB at times suggested a camaraderie between the prisoners, and reminded its audience that the reasons women tend to end up in prison are often quite different to those of the opposite sex. The Mars Room does a little of the same, but it’s far more bleak and violent. By comparison it maintains a certain distance from the other prisoners. Many of them are nasty people: murderers, baby-killers; they throw boiling sugar-water in each other’s faces. The novel seems to concede that a certain kind of person here exists beyond the understanding of a novelist.

It is a bad place and the world outside is not much better. This is California in the early 00s, a blasted landscape of decaying malls, vacant lots, fast food forecourts and dubious strip joints. It is an infinite suburbia, radically decentred, deprived by design. This is where Romy grew up; the novel opens with a long bus ride that takes her out that world and into the prison-world, somewhere nameless out in the vast west coast wilderness. Geography is notable in this novel, but most of these places seem to exist beyond names. You couldn’t point to them on any map. In this regard, prison seems like the ultimate kind of placelessness. Incarceration involves a deliberate separation of the inmates from the natural world — the barren panopticon of the yard and the running track could barely be called nature. Eventually the prisoners come to feel a kind of dread at the sight of the mountains and orchards in the distance. They are only symbols of failed escapes, can only suggest slow suffering in the wilderness.

But there are other aspects to this novel. From time to time a chapter will be written from another perspective, typically a male one. There is Gordon Hauser, a fairly average middle-class professor who runs classes for the inmates in Romy’s prison; and there’s Doc, a bent cop serving time for murder(s) in a separate facility for sensitive inmates (i.e. those most at risk from violent recrimination). Part of Hauser’s role is to stand in for the naivety of the expected audience of this book. He is educated, liberal, lightly contemptuous of the other staff, and mostly convinced that his role is to rehabilitate women who must have suffered some terrible evil to be where they are in life. He is confounded when some of the women tend towards exploiting his generosity. The reader might be inclined to be more generous towards the inmates. Even this doesn’t seem like an especially unreasonable thing for them to do, given the circumstances.

Doc, on the other hand, is one of a handful of characters here who are almost entirely without redeeming features. (Kennedy, the man who Romy killed, is the other; the single chapter dedicated to him is a portrait of entitled, predatory masculinity that is grim without reservation.) Doc is simply awful — a sneering shell of a man — uncaring, unapologetic, universally contemptuous. These chapters throw into relief a broader problem that the book has with the voice of its characters: all of them are too much of their own type. If Doc and Kennedy are villainous, Hauser is mostly just an object of pity. Romy, on the other hand, is nothing but sympathetic, and at times her voice seems less like her own and more like an authorial surrogate. The problem is not so much that she’s literate, or that her voice is devoid of an ‘accent’ that we might associate with poverty in the Dickensian sense; it’s that there’s something in it which stretches the confines of first-person narration a little too far, until it feels almost like the narrator has herself become omniscient. She reads like a person commenting on their own life as if it had been lived by someone else. (Perhaps you could argue that this is the point.)

Hauser, meanwhile, does not spend all his time in the prison. We see a good deal of his life outside, underlining the kind of everyday freedom he enjoys in the wider world. Sometimes he retreats to a cabin in the wilderness to read, to live amongst people totally unlike him and to think great thoughts. Other authors are invoked — Thoreau, naturally — but also Theodore Kaczynski, who was once known as the unabomber. A handful of extracts (notably uncredited) from Kaczynski’s diaries are blended into the chapters here. I wondered about this. Those chapters emphasise his violent reaction to the industrialised destruction he saw all around him, which was apparently so at odds with the measured quality of his prose.

Is that contrast as surprising today as it once was? I’m not sure. The Mars Room seems circumspect about the purpose of these passages. There’s a reluctance in the text to say what should be obvious: that Kaczynski went too far. Perhaps the novel is only trying to suggest that the impulse to tear it all down, by any means necessary, is still compelling. Who amongst us hasn’t been irritated by the sound of loud motorcycles, or appalled at the sight of logging in familiar patch of forest; who hasn’t felt the urge to do something?

Fifteen or twenty years ago it was the thing to hold up Kaczynski’s writings as being philosophically sound — worth reading, even if the ultimate results of his methodology were beneath contempt. I wonder if this is still the case. The outsider logic of the unabomber — the man who would set himself apart from the rest of humanity, in his cabin, with his rifle — has almost become the new normal. I say ‘almost’ because Ted thought we should do without, while the angry white men who came after him saw no reason to chase the same asceticism. But some of them were happy to take up rifles and to build bombs regardless. They saw something of the same threat in the world around them.

3 notes

·

View notes