#Sathya Kuranath

Text

Character, book, and author names under the cut

Sathya Kuranath- Mortal Engines Quartet by Philip Reeve

Jainan Nav Adessari- Winter's Orbit by Everina Maxwell

Gu Mang- Remnants of Filth by Meatbun Doesn't Eat Meat

Anastacia Alcroft LeBlanc- The Rosewood Chronicles by Connie Glynn

#Sathya Kuranath#Mortal Engines Quartet#Philip Reeve#Jainan Nav Adessari#Winter's Orbit#Everina Maxwell#Gu Mang#Remnants of Filth#yuwu#Meatbun Doesn't Eat Meat#Anastacia Alcroft LeBlanc#Undercover Princess#The Rosewood Chronicles#Connie Glynn#polls#lgbt books#queer book character tournament 2

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shrike, Gilgamesh, and the golem

“What are you for?” asked one boy at last, pushing to the front of the crowd. Shrike looked down at him. He pondered a while, thinking of something Dr Popjoy had told Anna.

“I AM A REMEMBERING MACHINE,” he said. (ADP.532-533)

The machine is shaped and wrought to purpose, but Shrike’s determination of his own reason for being is very much a recurring theme throughout the quartet. Perhaps this is why his self-identification as such caught my eye. He has shucked off all other purpose but to remember, which he proceeds to do by telling a story that begins with the opening lines of Mortal Engines. He assumes the role of a framing device—another sort of remembering machine, perhaps?

Dredged out of the past and put to new purpose—rather like Shrike himself—this technique has been used before. I am thinking of the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the eponymous hero gives up a life of adventuring, accepts the inevitability of his own death and, as I read it, goes on to write the tablets that almost make up the text. I don’t think it's a one-to-one equivalence in either case: neither Shrike nor Gilgamesh would tell the stories quite as we read them, but I think the texts can be read as echoes of the stories they claim have been told.

According to the text of Gilgamesh, the story can be found in the city of Uruk, written on lapis tablets, but the tablets on which this is written—the tablets we have today—are made of clay. What role does the tablet play for Gilgamesh? A framing device? A remembering machine?

Memory, history, archaeology; all these are central concerns of the quartet, driven home frequently by Tom Natsworthy, the would-be historian, and his fictionalising counterparts Valentine and Pennyroyal, each of whom attain a level of renown that Tom never does. Much of the series’ humour derives from pieces of more-or-less contemporary culture filtered through hundreds or thousands of years of post-apocalyptic life. What is the truth? What is history?

“For a somewhat sensationalized but passably accurate account of London’s momentous push east in 1007, see Mortal Engines by Philip Reeve.” So says The Traction Codex, listing Reeve’s work alongside those of Nimrod Pennyroyal (Predator’s Gold) and Sathya Kuranath (A True History of the Wind Flower, “generally regarded as unreliable”). The Codex formed the basis for The Illustrated World of Mortal Engines, for which this particular line was removed. Like the multiple recreations and translations of Gilgamesh, and the conflicting accounts of various histories given by different parties in the quartet and the prequel trilogy, the past is not straightforward. From Janis Dawson: “Reeve’s novels are an eclectic, sometimes bizarre, blend of genres and forms punctuated with scores of parodic references to classic texts, histories, popular literature, film, and advertising blurbs. They are, in effect, literary Jenny Hanivers”. (p. 143)

Clay constitutes the tablets of the Gilgamesh epic, but within the text, it is from clay that the goddess Aruru forms the wild man, Enkidu. Rival, companion, perhaps lover to Gilgamesh, Enkidu is a formidable warrior and loyal friend. The body of the wild man and the material on which the text survives; clay is the substrate of life and words. A parallel can be found in Jewish folklore: formed from clay, the golem was brought to life by writing one of the names of God on a piece of paper, which would be placed in the mouth or forehead. In various tales, the golem is both protector and threat. Terry Pratchett plays with this idea in Feet of Clay: the words in our head make us who we are. We are the material upon which history is written.

Perhaps fittingly, no one conclusion jumps out at me. The histories we create, or remember, make us who we are? There is no escaping the past? What we choose to believe, about ourselves or about history, matters? Shrike is a futuristic take on the golem? The remembering machine, whether clay (juncture of life/writing and earth) or cyborg (juncture of human/data and machine), is a letter sent forward into the future, as deadly and implacable a technology as any Slow Bomb?

Variously, Mortal Engines is claimed as a 2001 fictional children's novel, as Shrike’s remembering, as Philip Reeve’s sensationalized but passably accurate account of events... Perhaps it is necessary for these histories to co-exist with each, not in spite of but because of their differences.

Note: The Traction Codex doesn’t have page numbers, but it’s ebook only, so it should be easy enough to track down any quotes. For Gilgamesh I’m referring to Benjamin Foster’s translation (Second Norton Critical Edition), and for golems I’m relying on Wikipedia. Let me know if you want a copy of the Dawson article, though I think the line I quoted is the only bit worth reading.

#shrike and the scriven make for an interesting parallel i think#both products of the black centuries dragged out of the north. twisted legacies of the scrivener institute. built to last#but where the scriven were made to preserve life. shrike was made to end it#the scriven were to be a hand on the yoke of history. shrike to be a tool in the hand#but the hand wasted away and the tool kept on doing its grim work until it wasn't a tool any more#shrike#mortal engines#reeve_thoughts

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

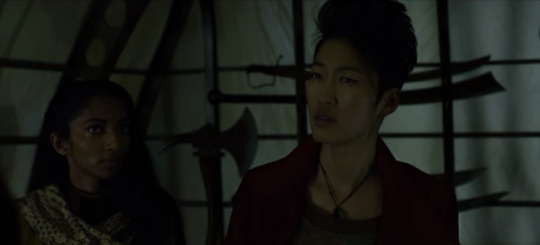

Menik Gooneratne as Sathya Kuranath in Mortal Engines (2018)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On the plus side: Anna and Sathya!!!

104 notes

·

View notes