#Quentin Keynes

Text

Mongoose lemur

By: Quentin Keynes

From: The Fascinating Secrets of Oceans & Islands

1972

#mongoose lemur#lemur#primate#mammal#1972#1970s#Quentin Keynes#The Fascinating Secrets of Oceans & Islands

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

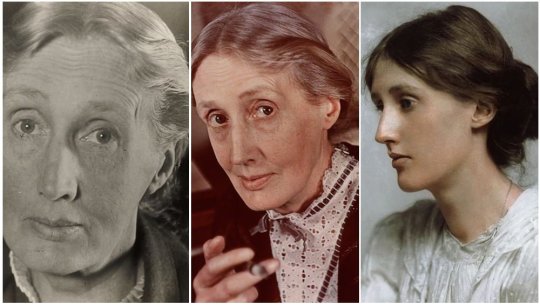

Virginia Woolf's politics are not (male) party politics, but feminist politics, and I think that there are few areas of feminist thought to which she has not made a contribution. Her fundamental thesis that those who are in power perceive the world differently (and determine the scale of values) from those outside the power structure (and whose values are therefore decreed to be deviant, eccentric, neurotic, irrational, inexplicable) is for me one of the touchstones of feminism, and helps to explain the way she has been treated, removed from the realms of philosopher or political analyst, and cast into the mould of delicate and elaborate artist. (There is even a jarring of images if one tries to visualise Virginia Woolf as a tough political thinker - which indicates how pervasive the portrayal has been - yet in Three Guineas, which she carefully planned in order to 'strike very sharp and clear on a hot iron' (Carroll, 1978, p. 103), her avowed intention was - as is the title of Carroll's essay - ‘To Crush Him In Our Own Country’, which is a tough stand in the face of the drift to war.)

Woolf herself would not have been surprised at the treatment she has received, consigned to a separate and acceptable women's sphere outside the mainstream of intellectual recognition, for after all, were women not literally locked out of men's libraries? She understood this process and it was precisely the one she was attempting to subvert with the documentation of women's heritage - and possibilities - in A Room of One's Own. She tried to construct a coherent context in which women's values were meaningful and invested with layers of symbolism, and celebration - no mean feat in a society in which the symbolism of the phallus is so pervasive and where men consistently celebrate their own achievements, but where women's imagery and celebration is invisible. And she tried to do this because she recognised the political nature and the significance of the act of creating a different and autonomous women's culture outside the control of men, although still rooted in the culture of men, and in opposition to it.

When Florence Howe asserts that women's studies is not a ghetto but the centre of the construction of knowledge, based on the experience of half the population (with the implication that it is men's studies which is on a side-track), she is doing nothing less than Virginia Woolf, who made it a virtue to be an outsider in an exploitative and oppressive society. Women can best help society, can best serve the interests of achieving freedom, equality and peace, by not helping men, argues Woolf, in Three Guineas, by not imitating them or supporting them in their aggression, violence, and war. She urges women to stay out of patriarchal institutions, to find their own critical and creative means of promoting change (1938, p. 206), and to remain free from unreal loyalties, to remain outside that ‘loyalty to old schools, old colleges, old churches, old ceremonies, old countries’ (ibid., p. 142).

This was the book Leonard Woolf decreed as not very good, indeed to which he was hostile: ‘“Maynard Keynes was both angry and contemptuous: it was, he declared, a silly argument and not very well written.” E.M. Forster thought it "the worst of her books." Quentin Bell perhaps best displayed the depth of incomprehension of the book in reporting his own reactions: “What really seemed wrong . . . was the attempt to involve a discussion of women's rights with the far more agonising and immediate question of what we were to do in order to meet the ever growing menace of Fascism and War. The connection between the two questions seemed tenuous and the positive suggestions wholly inadequate”’ (Carroll, 1978, p. 119). Bell missed Virginia Woolf’s thesis that tyranny begins at home; Adrienne Rich (1980) did not. In her appeal to women to be 'Disloyal to Civilization' she quotes and builds upon Woolf's concept of ‘freedom from unreal loyalties’. To Rich, as to Woolf, it was the values of a society controlled by men which women must disown, and challenge, in the interest of freedom, equality and peace.

-Dale Spender, Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them

#dale spender#virginia woolf#male violence#female oppression#feminist thought#women’s studies#women’s culture

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Speak its Name! Quotations by and about Gay Men and Women

Edited by Christopher Tinker. Introduction by Simon Callow.

This collection of quotations by and about gay people celebrates the advances of the international LGBT community over the past 50 years. Amusing observations by Noël Coward, Tallulah Bankhead, Quentin Crisp, Boy George and Ian McKellen are interspersed with interviews with Dusty Springfield, Alan Bennett, Freddie Mercury, Clive Barker, George Michael and William S. Burroughs, and diary entries by Kenneth Williams, Joe Orton, W.H. Auden and John Maynard Keynes. John Gielgud and Alan Turing’s accounts of being arrested contrast with letters from Violet Trefusis to her lover Vita Sackville-West, King James I to the Marquis of Buckingham, and Benjamin Britten to his partner Peter Pears. Contributions by Oscar Wilde, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, John Wolfenden, Field Marshal Montgomery, Lord Arran, Margaret Thatcher, Waheed Alli and David Cameron demonstrate enormous developments in gay rights. Reflections from celebrity icons such as Julie Andrews and David Beckham are also featured, alongside a wealth of reproductions.

#Speak its Name#quotations#gay#queer#Christopher Tinker#editor#simon Callow#actor#books worth reading

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (7/11/23)

Duncan Grant (Scottish, 1885-1978)

The Hammock, Charleston (c. 1921-22)

Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 147.3 cm.

Private Collection

The scene depicted here is the edge of the farm pond at Charleston, the artist's country home which he shared with Vanessa Bell, her children and, at the time of this painting, with Maynard Keynes. Charleston was a rented house in the middle of a working farm on the Firle Estate, Sussex. In the hammock is Vanessa Bell; her and Grant's daughter Angelica (b. 1918), pulling a toy animal, is to the right; Quentin Bell (b. 1910) rocks the hammock in the foreground, next to his and his brother's tutor, Sebastian Sprott; and Julian Bell (b. 1908) punts on the pond. The house and walled garden are to the right and the Sussex Downs start their ascent on the horizon at the top left. Charleston's agricultural setting is suggested by the horse and cart on the lane and part of the barns at top right.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Wittgenstein

John Maynard Keynes (John Quentin) sits stiffly in a straight-backed chair while working a white, circular jigsaw puzzle and advises Ludwig Wittgenstein (Karl Johnson), “There’s nothing better than a warm sated body.” It’s a thrilling moment of separation between meaning and image that, nonetheless, makes some kind of aesthetic sense, like many of the images in the films of Derek Jarman. To call his WITTGENSTEIN (1993, Criterion Channel through month’s end) a biography of the man often called the 20th century’s greatest philosopher, would be like calling Martha Graham’s choreography of “Appalachian Spring” a blueprint for a barn. Jarman presents a series of images often separated from their meanings to create a new set of meanings. In this film, the images are lyrical and even at times comic meditations on the philosopher’s thought and life, sometimes narrated by Wittgenstein as a child (Clancy Chassay) and with key events announced by his sister, who’s shocked that he’s enlisted in World War I or is trying to publish his first philosophical work. Other elements of his life, like his homosexuality, are just givens, with Wittgenstein pondering the loneliness of the soul while in his lover’s arms. Jarman manufactures a personal conflict to explain Wittgenstein’s break with his mentor, Bertrand Russell (Michael Gough, who’s glowing as if it’s a relief not to be starring in cheap horror or a BATMAN film), and that scene rings false, but the comment on class underlying it makes sense (class is the elephant in the room in most modern British literature). Wittgenstein’s lover (a fictional character played by Kevin Collins) is the child of miners who sacrificed everything to send him to Cambridge. The philosopher, who romanticizes physical work, influences him to leave Cambridge and get a job as an engineer. Later, Collins is slacking off at his job to contemplate a game of dominos, because you can take the boy out of the philosophy seminar but you can’t take the philosophy seminar out of the boy.

0 notes

Text

Duncan Grant in Lincoln

I am unsure what the public perception was of Duncan Grant in the 1950s, if people knew he was homosexual or if Vanessa Bell's infatuation with him masked that.

Either way it is surprising to see murals by Grant in a Cathedral given attitudes to such bohemian artists in the church. But in Lincoln Cathedral there is a cell with his homoerotic murals designed on the theme of Lincoln's history in the wool trade.

As with anything Bloomsbury, nothing is simple, so here is a bit of background on Bell and Grant:

Vanessa Bell, married Clive Bell in 1907, and had two sons in quick succession. The couple had an open marriage, both taking lovers throughout their lives. Vanessa had affairs with art critic Roger Fry and with the painter Duncan Grant. Vanessa succeeded in seducing Duncan one evening and she became pregnant in the spring of 1918, having a daughter, Angelica in 1918, whom Vanessa and Clive Bell raised as his own child.

In 1942, aged 24, Angelica married David Garnett. The relationship had begun in the spring of 1938, when Garnett was married to his first wife, Rachel "Ray" Marshall, who was dying of cancer. Angelica had four daughters with Garnett.

Garnett was a member of her parents' circle, a former lover of Duncan Grant who had also attempted to seduce Vanessa Bell. When Angelica was born, Garnett had written to Lytton Strachey saying of the baby: "Its beauty is the remarkable thing … I think of marrying it; when she is 20 I shall be 46 – will it be scandalous?"

In fact Garnett was nearly 50 at the time of their marriage. Despite their consternation, Angelica's parents did not inform their daughter of these details of Garnett's past, although various associates of the family did attempt to warn her against the marriage: John Maynard Keynes had her to tea. Angelica lost her virginity to Garnett in H.G. Wells's spare bedroom. ‡

They were a bohemian lot.

The Russell Chantry, Lincoln Cathedral, before the Duncan Grant murals.

The Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Fund, set up in 1952 by the widow of the illustrator and historical painter to promote murals in public places, had placed a notice in The Times on 2 May 1952 inviting proposals. One of these had come Duncan’s way, helped no doubt by Vanessa’s presence on the Fund’s committee, and he was to decorate the chapel dedicated to St Blaize, patron saint of the wool industry, in the Russell Chantry at Lincoln Cathedral. †

St Blaize was a doctor from a rich family who renounced his possessions and lived in caves and hillsides, caring for the animals.

After seven years the murals where finished in 1959, they where effectively hidden from public view. The subjects Grant painted were just too homoerotic for the church at that time. The space was used a broom-cupboard for a while in the 1970s.

With the mass publications of various Bloomsbury books and the rise of interest in Duncan Grant, the chapel was re-opened for public view after restoration in 1990. However when I went in the summer of 2018 the room was locked and wasn’t mentioned on the handout map given when you enter the building.

Below is a study for the Christ figure that Grant painted, the study is likely of Paul Roche, Grants lover and painting model.

In London, Duncan had begun to draw Paul in some of the poses that he needed: for the men shearing sheep and for the full-length figure that dominates the altar wall, the Good Shepherd, carrying a sheep on his shoulders.

On the wall opposite he was to paint a view of medieval Lincoln, with a busy harbour scene in the foreground. On the right-hand side men heave bales of wool, their balletic poses echoing the curves found in the ships’ prows, while on the left three statuesque figures (Angelica, Vanessa and Olivier) are linked with the men by the small boy pulling at Olivier’s hand. †

The large ships with the homoerotic and suggestive men are likely what caused the greatest offence to Anglican eyes in the 1960s. The men bending over normally in front of other men’s groins and perfectly painted bums.

As mentioned above the three women below are from Grant’s household. Angelica Bell his biological daughter, Vanessa Bell and Olivier Bell, the wife of Vanessa and Clive’s son Quentin Bell.

Even the little boy looks a little phallic with his flag stuck out at a saucy angle.

In October 1955 Duncan, while painting his Lincoln murals, jumped off a high stand on to a stool that overturned, and cut his head on an electric fire. The accident was minor, but the murals he was painting played a large part in helping him through a low period, for the public at this time showed little interest in his work. †

In the image below you can see a round window above the door painted in with St Blaise looking toward the alter. By the time Grant had finished the works he was in his mid-seventies.

In 1958 Duncan completed the Lincoln murals, which had for so long dominated the studio at Charleston. In order to see them installed, he and Vanessa travelled north and booked in at the White Hart. †

He had put a great deal of thought and labour into this decorative scheme, and at one point had used paper cut-outs to help him decide on the exact positioning of the sheep on either side of the Good Shepherd. Paul had modelled for the young beardless Christ. Consciously or unconsciously, Duncan had drawn on an early Christian tradition which, to ease the transition from paganism to Christianity, depicted Christ in a manner reminiscent of Mercury. Duncan’s Good Shepherd, surrounded by a mandorla of light, fills the centre of the altar wall and faces the view of medieval Lincoln on the wall opposite. †

The picture below is a study in the art gallery in Lincoln of the mural back wall with the original headdresses on the three women and the rest of the scene remarkably similar to the final result, other than Lincoln looks more Italian in the final mural.

Study for The Wool Staple in Medieval Lincoln

The final work was painted in oil on fibrous plaster-boards, which gives to the oils an impression of the chalky surface of fresco. Once the panels arrived in Lincoln in the summer of 1956 they were attached to the walls on battens over the following two years. Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell attended the unveiling in July 1959, when they stayed as usual in the White Hart Hotel. Vanessa died two years later, while Grant was to live to ripe old age, still travelling and painting and enjoying exhibitions, often with his friend Paul Roche, the model for The Good Shepherd.†

† Frances Spalding - Duncan Grant, 1997

‡ Angelica Garnett - Wikipedia

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

olennawhitewyne replied to your post

“I think the person who asked "how is Yuuri still working for MI6" is...”

These people who think "no one could be gay in the U.K. before it was legal" should look up some stuff about Benjamin Britten

Or indeed:

Siegfried Sassoon

W.H. Auden

Quentin Crisp

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Brian Epstein

Francis Bacon

John Maynard Keynes

E.M. Forster

James Bernard

to name but a few. Gay people in ‘always having existed’ shocker!!

#olennawhitewyne#particularly quentin crisp because he was gay enough for like five dudes#quentin crisp was actually gayer than victor nikiforov#an astounding achievement

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bugün sizlere fotoğrafçılık mesleğinin yanı sıra çevre savunucusu olarak tanınan Peter Beard’in vefatını haber verirken aynı zamanda hayatını da paylaşmak istiyorum. 1938 senesinde New York’ta doğan Beard, çocukluğunu doğa sevgisinin pekiştiği Tuxedo Park yakınlarında yaşayan anneannesinin yanında geçirmiştir. İlk fotoğraf makinası olan Voightländer marka makinasını anneannesi sanatçıya hediye etmiştir. Çektiği fotoğraflarla ve tuttuğu günlüklerle tanıdığımız sanatçının bu iki sevgisi gençliğine dayanmaktadır. On yedi yaşında Charles Darwin’in torunu gezgin Quentin Keynes ile birlikte çıktığı Afrika seyahati tam anlamıyla hayatını değiştirmiştir. Seyahat dönüşü Yale Üniversitesi’nde öğrencileri tıp fakültesine hazırlayan tıp öncesi eğitim alabileceği bir bölüme girmiş fakat sonrasında sanat sevgisi ağır basarak sanat tarihçisi Vincent Scully, sanatçı Josef Albers ve ressam Richard Lindner’ın yanında eğitim alabileceği sanat çalışmalarına ağırlık vermiştir. Afrika hakkındaki araştırmaları okul zamanı da son bulmayan sanatçı bitirme tezi yerine Afrika’da tuttuğu günlükleri tezi için okula postalamıştır. 1960lı senelerde Kenya’nın ilk başbakanı Jomo Kenyatta’dan Ngong Tepeleri yakınında bir mülk olan ve hayatı boyunca ev olarak kullanacağı Hog Ranch’i yerel flora, fauna ve yaşayan halkı filme almak, fotoğraflamak, yazmak ve belgelemek için özel bir izin almıştır. 1965 senesinde ilk kitabı olan The Game of the End isimli kitabında hayvan, toprak ve insan arasındaki dengesizliği belgelemek için çalışmıştır. Bu çalışması sonrası çıkaracağı her çalışmada ve kitapta da belli olacağı gibi hayvanlarda görülen açlık, hastalık ve devasa boyutlara varan ölümleri belgelemiştir. - Yazının devamını yorum kısmında okuyabilirsiniz. - https://www.instagram.com/p/B_Pk5oBgvhZ/?igshid=1cqktziwvo0wt

0 notes

Photo

#Repost @clintroenisch with @make_repost ・・・ Peter Beard has been missing from Montauk for 6 days. For those of you who don’t know him: “He was just a 20-year-old Yale University undergrad when, armed with Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa, he arrived in Nairobi for the first time, bought a fourth-hand Land Rover, set out to track wild game and lived on passion fruit and roasted flanks of freshly slaughtered zebra. In the Seventies, Beard once found a game poacher on his 49-acre property, tied the man up in his own animal snare wires, stuffed a glove in his mouth and left him there. Jackie Kennedy and her sister Lee Radziwill were among Beard’s confidantes, as well as Bianca Jagger and Barbara Allen. His second marriage was to Cheryl Tiegs and he has been credited with discovering Iman. He spent the Seventies running with Andy Warhol’s clique. Beard has never held his preferred medium in high regard. “Most photographers are idiots. That’s the horrendous truth. It’s a parasite field. Because all you have to do is squeeze your index finger, and you’ve got yourself a profession,” Beard once said. Born in 1938 into New York aristocracy (his great-grandfather, James J. Hill, was the founder of the Great Northern Railway, and his grandfather, tobacco heir Pierre Lorillard, established Tuxedo Park, New York), Beard grew up on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and was educated at Buckley and Pomfret before enrolling at Yale as a pre-med student, later switching his major to fine arts. He first travelled to Kenya when he was 17, to work with Charles Darwin’s grandson and explorer Quentin George Keynes on a documentary about rhinos, taking photographs with a Voigtländer camera his grandmother had given him. His first taste of Africa touched him deeply, but his love affair with it began in earnest just after his graduation from Yale, when he returned to Kenya to document the plight of over 35,000 starving elephants among a wasteland of eaten trees in Tsavo National Park. These graphic and sometimes shocking images formed the core of his first book, The End of the Game, published in 1965. (at Montauk, New York) https://www.instagram.com/p/B-ufwD_l7Sg/?igshid=1ntck0ppwm817

0 notes

Text

Virginia Woolf tentou ‘curar’ sua loucura pelo suicídio

Na manhã de sexta-feira, 28 de março de 1941, um dia claro, luminoso e frio, Virginia foi como de costume ao seu estúdio no jardim. Lá, escreveu duas cartas e atravessou os prados até o rio. Deixando a bengala na margem, ela esforçou-se para pôr uma grande pedra no bolso do casaco. Depois encaminhou-se para a morte.

Na manhã de sexta-feira, 28 de março de 1941, um dia claro, luminoso e frio, Virginia foi como de costume ao seu estúdio no jardim. Lá, escreveu duas cartas e atravessou os prados até o rio. Deixando a bengala na margem, ela esforçou-se para pôr uma grande pedra no bolso do casaco. Depois encaminhou-se para a morte

Em 28 de março 2020 completou 79 anos que a escritora inglesa Virginia Woolf se matou. Virginia, que hoje tende a ser comparada (desfavoravelmente) a James Joyce, que ela considerava (invejosamente) um operário autodidata, morreu aos 59 anos, jogando-se no Rio Ouse, em 1941.

A obra de Virginia permanece gerando polêmica. Para alguns, ainda é inovadora. Para outros, teria envelhecido. A revolução de Virginia estaria obscurecida pela revolução de Joyce. Talvez o mais justo seja não comparar os dois autores, percebendo, antes, que há diferenças, apesar de estarem próximos (literalmente), entre eles.

Sobre sua vida, é possível saber alguma ou muita coisa, principalmente depois da sensível e abrangente biografia de Quentin Bell. Infelizmente, a autobiografia de Leonard Woolf ainda não foi traduzida para o português. Leonard foi a pessoa que mais entendeu Virginia. É provável que ela tenha escrito a maioria de suas obras porque teve o apoio firme do marido e amigo. Leonard sacrificou-se pelo talento de Virginia. Trata-se do sacrifício do menor talento pela afirmação do maior talento. O casamento sequer lhe proporcionou prazer sexual.

“Virginia Woolf — Uma Biografia” (1882-1941), do escritor Quentin Bell, sobrinho de Virginia e filho de Vanessa e Clive Bell, é um livro belíssimo e traz fotografias excelentes. O meu texto é uma pálida síntese da esplêndida obra de Quentin Bell — publicada no Brasil pela Editora Guanabara, com tradução de Lya Luft. O único senão é a revisão, catastrófica, como de hábito no “nosso” doce Bananão.

Para sorte dos leitores, a biografia, embora esgotada, pode ser encontrada em sebos. Um detalhe relevante para os preguiçosos leitores brasileiros, filhos diletos da televisão: a biografia tem 614 páginas. É um cartapácio. Um detalhe convidativo: o texto de Quentin Bell é agradável e não tem ranços acadêmicos.

Como disse, meu texto é uma pálida síntese do livro de Quentin Bell. Há histórias interessantíssimas sobre Virginia, que tinha o apelido de “Cabrita” , mas, se fosse contar todas, precisaria de mil páginas e o leitor não leria o livro. Registrarei mais o “crescimento” efetivo e literário de Virginia.

Os familiares de Virginia, por parte de pai, eram todos escritores. Eram da alta classe média inglesa. Virginia Stephen nasceu no dia 25 de janeiro de 1882. Só aprendeu a falar depois dos 3 anos. Aos 6 anos, falava bem e contava estórias deliciosas. Era uma espécie de Hemingway de saias. Mas nada sacava de aritmética.

Ainda jovenzinha, foi bolinada pelo meio-irmão George. Pode ter sido a causa de sua permanente frigidez sexual. Antes dos 13 anos, depois de várias leituras, buscando sem conseguir um estilo próprio, começou a copiar Nathaniel Hawthorne. Aos 16 anos, apaixona-se por uma mulher, Madge. Nada de sexo. Puro amor. Afeto. Paixão adolescente.

Virginia era uma leitora compulsiva. Queria compensar, em tempo recorde, o fato de não ter educação formal, universitária. Os irmãos Thoby e Adrian estudaram em Cambridge. Ela não pôde estudar lá. Ficou ressentida a vida inteira. A saída foi ler bastante, aprender sozinha ou com o pai, Leslie Stephen, um homem sábio mas de personalidade frágil e difícil.

Depois da morte do pai, em 1904, Virginia tenta se matar, pulando de uma janela, mas não consegue. A janela era baixa e ela se machucou muito pouco. Mas a alma estava profundamente ferida. A garota estava tão maluca que ouvia os pássaros cantando em grego. E já estava apaixonada por outra mulher — Violet Dickinson. De novo, nada de sexo. É o que diz o informadíssimo Quentin Bell. Seu sobrinho, vale ressaltar.

Entretanto, apesar de parente, Quentin aparentemente não esconde fatos, o que pode ser comprovado lendo outras biografias de Virginia. O autor é franco e claro, embora Lya Luft, a tradutora, procure termos mais suaves para falar do ���lado” lésbico de Virginia e do homossexualismo dos amigos da escritora. Safismo e sodomita são palavras que estão registradas nos dicionários brasileiros, mas não no vocabulário do nosso leitor médio. No lugar de sodomita, para ficar mais claro, a tradutora poderia ter ousado e escrito “viado” (com i) ou, pelo menos, “homossexual”. Mas isso não importa tanto. São detalhes de nenhuma importância.

Em 1904, por interferência de Violet, Virgínia começa a escrever críticas (não assinadas) para o “The Guardian”. Em 1905, Thoby começa as noites de quinta-feira, no famoso bairro de Bloomsbury, com a presença de Saxon Sydney-Tuner, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey (irmão do grande tradutor de Freud, James Strachey), Clive Bell e Desmond MacCarthy. Jack Pollock, E. M. Forster, Bertrand Russell e John Maynard Keynes também participavam da “farra” intelectual.

Henry James, amigo do pai de Virginia, não gostou do grupo de Bloomsbury, que achava de baixo nível. Rebelde, o grupo usava roupas esdrúxulas e falava palavrão. Vanessa, pintora, mãe de Quentin Bell, também participava das reuniões e era adepta do “sexo livre”. Ela própria era chifrada por Clive Bell e chifrava o marido. Nenhum dos dois, porém, gostava das chifradas. O liberalismo na prática é uma piada.

As reuniões de Bloomsbury ajudaram imensamente na formação da “inculta” Virginia. Os participantes eram intelectuais, alguns em formação e, outros, com alto preparo. Ela absorvia, “antenada” e “babando”, tudo que eles falavam ou sugeriam. Mas a morte de Thoby, o irmão e amigo adoradíssimo, bagunça a família Stephen, que nunca fora muito ajustada. Vanessa, desesperada, se casa com o garanhão come-tudo Clive Bell. Virginia não gostou do casamento. No início. Ela e Adrian, o mais moço dos irmãos e o mais atrapalhado, vão morar juntos.

Os amigos e parentes declaram: “Virginia precisa casar”. Queriam arrumar uma pessoa para cuidar da “incuidável” Virginia. Irritada, Virginia escreveu à amiga Violet: “Eu queria que todo mundo não me ficasse repetindo que devo casar. Será uma irrupção da rude natureza humana? Eu acho repulsivo”. Apesar de sua ira, os amigos e parentes continuaram insistindo para que ela se casasse.

Entre 1907 e 1908, Virginia começa a escrever “Melymbrosia”, mais tarde publicado como “The Voyage Out” (este primeiro romance de Virginia foi editado no Brasil sob o título de “A Viagem”). Exigente, Virginia queimou sete versões de “The Voyage Out”. Ela não publicou ficção até os 33 anos.

“Seu laconismo literário era em parte resultado de timidez; ainda ficava aterrorizada com o mundo, aterrorizada de se expor. Mas unia-se a isso outra emoção, mais nobre — um alto conceito de seriedade de sua própria profissão. Para produzir algo que atingisse seus critérios particulares, era necessário ler vorazmente, escrever e reescrever continuamente, e, sem dúvida, se não estava escrevendo na hora, agitar as ideias que expressava em sua mente”, nota Quentin Bell.

No plano afetivo, a vida de Virginia continuava difícil. Lytton Strachey quis se casar com ela, mas não deu certo. Outro amigo de Virginia, o competente e célebre economista John Maynard Keynes, embora tenha se casado com uma bailarina, também era sodomita (palavra bastante usada por Quentin Bell). Keynes morou na casa de Virginia e Adrian.

Em 1912, Leonard Woolf e Virginia se casam. Leonard se apaixonou por Virginia. Doce e perdidamente. O casamento foi um grande “negócio” para Virginia. A união com Leonard aumentou o seu equilíbrio emocional e a sua segurança como escritora. O curioso é que a família Stephen não avisou Leonard dos problemas de saúde de Virginia. Tudo indica que a família procurou esconder que Virginia era “meio louca” com medo que Leonard desistisse do casamento. O casamento não agradou Clive Bell. Clive andou tirando umas casquinhas de Virginia. Mas sossegue: o vigoroso marido de Vanessa não conseguiu papar Virginia. Só tirou casquinhas. Virginia, diga-se, gostava do atrevimento de Clive.

Leonard adorava Virginia, sua capacidade intelectual, e não se preocupava com a frigidez sexual dela. Quentin Bell, um biógrafo às vezes discreto, sugere que Virginia “considerava o sexo não tanto com horror, mas com incompreensão; havia em sua personalidade e em sua arte uma qualidade estranhamente etérea, e, quando as necessidades literárias a compeliam a considerar o prazer sexual, ela se afastava ou nos revelava algo tão distante de bolinas e empolgações quanto a chama de uma vela é distante de seu sebo”.

Virginia conclui “The Voyage Out” e o entrega à editora. Doente, pensa que a libertação (a cura) está no suicídio. Toma 6,5 gramas de veronal e quase morre. Quentin Bell registra que até 1913, data da tentativa de suicídio, Freud era pouco conhecido na Inglaterra. “Ernest Jones começou a praticar em Londres em 1913”, informa Quentin. Virginia não se interessava muito por Freud. Mas Leonard achava que o conhecimento das ideias de Freud poderia ser útil no seu tratamento.

“The Voyage Out” foi publicado em março de 1915. Os amigos de Virginia e a crítica gostaram. Edward Morgan Forster (autor de “Passagem Para a Índia”, mais conhecido no Brasil pelo bom filme de David Lean), que também era gay renitente, elogiou o livro de Virginia no “Daily News”: “Eis finalmente um livro que chega ao mesmo patamar de ‘O Morro dos Ventos Uivantes’, embora por um caminho diferente”. A critica era esperada ansiosamente por Virginia. Queria ver se seu talento era confirmado.

“Virginia”, escreve Quentin Bell, “estava sempre imaginando que, para o mundo exterior, [seus romances] pudessem parecer simplesmente doidos ou, pior ainda, fossem realmente doidos, seu horror à zombaria rude do mundo continha o medo mais profundo de que sua arte, e por isso ela mesma, fosse uma espécie de impostura, um sonho imbecil sem valor para os outros. Por isso, para ela, uma nota favorável valia mais que o mero elogio; era uma espécie de certificado de sua sanidade mental”.

“O problema”, continua Quentin, “deve estar presente quando pensamos em sua extrema sensibilidade à crítica, uma sensibilidade que podemos considerar mórbida e que realmente, em certo sentido, era mórbida, pois nascia de um estado enfermiço. Os ataques e açoites da crítica, que seriam facilmente enfrentados por um organismo mais robusto, no caso dela podiam reabrir feridas que jamais se tinham curado inteiramente e que nunca deixariam de ser muitíssimo delicadas”.

Quentin Bell nota que a saúde de Virginia melhorou em 1915 por causa das criticas favoráveis. Virginia, temendo a crítica, escreveu: “Imagine acordar e descobrir que se é uma fraude. Esse horror era parte da minha loucura”.

Em 1917, um tanto ranzinza mas admirada, Virginia escreveu à adorada e protetora irmã Vanessa: “Tive um breve encontro com Katherine Mansfield; que me parece um caráter desagradável mas enérgico e absolutamente inescrupuloso”.

Quentin Bell explica bem: “Elas [Virginia e Mansfield] sempre tendiam a discordar, mas na verdade nunca discordariam. Unidas pela devoção à literatura e divididas na sua rivalidade como escritoras, achavam uma à outra sobremodo atraentes, mas muito irritantes. Ou pelo menos eram esses os sentimentos de Virginia. Ela admirava Mansfield; também estava fascinada por aquele lado da vida de Katherine que ficava além da sua própria capacidade emocional”.

“Katherine”, revela Quentin, “andara pelo mundo, ficara magoada; dera vazão a todos os instintos da fêmea, dormira com todo tipo de homens; tornara-se objeto de admiração — e piedade. Era interessante, vulnerável, talentosa, encantadora. Mas também se vestia e se portava como uma prostituta. Penso que Katherine Mansfield retribuía a admiração de Virginia e também sua animosidade. Virginia com certeza apreciava bastante o talento de Katherine, a ponto de querer editar um de seus contos”.

É provável que Virginia tenha lançado um olhar masculino em Katherine Mansfield. O homem em geral deprecia a mulher inteligente e diferente, mas também a cobiça sexualmente. Outra coisa: Virginia não gostava de elogiar escritores vivos. Só deu importância a D.H. Lawrence, o autor de “Mulheres Apaixonadas”, depois que ele morreu. Os vivos eram seus concorrentes.

Junto com Leonard Woolf, Virginia foi dona da Hogarth Press, que editou grandes escritores e poetas, como Katherine Mansfield e T.S. Eliot, além do psicanalista Freud. Quentin Bell e os outros biógrafos revelam algo curioso: Virginia escrevia um romance vigoroso (como “As Ondas”) e, em seguida, um romance mais leve e fácil (como “Os Anos”). Parece que tal artifício visava tranquilizar os seus nervos e, ao mesmo tempo, testar novos caminhos para o romance. “O romance peso-pesado é sucedido por um livro peso-pluma — que ela chamava uma piada”, só que Quentin Bell não acha que “Noite e Dia” seja uma piada. Não acha o livro bom. Mas não concorda que seja totalmente ruim.

O manuscrito de “Ulysses”, de James Joyce, foi oferecido à editora de Virginia, que não pôde ou não quis publicá-lo. Quentin Bell tenta explicar: “Era uma obra que Virginia não podia rejeitar nem aceitar. O poder e a sutileza da obra eram evidentes o bastante para despertar a admiração dela e, sem dúvida, inveja. Parecia-lhe ter uma espécie de beleza, mas também um brilho rude, arguto, de sala de fumantes. Joyce usava instrumentos parecidos com os dela, e isso era doloroso, pois era como se a pena, sua própria pena, tivesse sido arrancada de suas mãos e alguém rabiscasse com ela a palavra “foda” no assento de um vaso sanitário”.

Virginia “também sentia”, segundo Quentin, “que Joyce escrevia para um pequeno grupo, e, quando se refere a ele, escreve ‘essa gente’ — como se o classificasse tal qual Ezra Pound e não sei que outras figuras do ‘submundo’. A reação dela talvez seja significativa; a rudeza gratuita e impudente de Joyce fazia-a sentir-se, súbito, desesperadamente ‘uma dama’. Mesmo assim foi perspicaz o bastante para ver que era algo digno de ser publicado; era claro, também, que estava absolutamente além da capacidade técnica da Hogarth Press”. Para mim, era o lado mundano de Joyce que não agradava Virginia. Ao contrário de Joyce e de Proust, não sacava muito do lado “sujo” da vida.

O leitor pode ler mais sobre o assunto na admirável biografia de James Joyce escrita pelo americano Richard Ellmann. “Os Woolfs disseram-lhe (à emissária de Joyce) que não poderiam imprimir (‘Ulysses’) porque levaria dois anos na sua impressora manual, embora dissessem que estavam muito interessados nos quatro primeiros episódios que leram. Na verdade parecem tê-lo considerado ‘vulgar’, embora Katherine Mansfield, que deu uma olhada no manuscrito certo dia enquanto os visitara, tenha começado ridicularizando-o e depois de repente tenha dito: ‘Mas há qualquer coisa nisso: uma cena que deveria figurar, suponho, na história da literatura’.”

A história de Virginia Woolf escritora é tão interessante como a de Virginia Woolf editora. T.S. Eliot foi amigo de Virginia e a Hogarth Press editou seus primeiros poemas e o mais famoso, “A Terra Estéril”. Virginia tentou tirar T.S. Eliot do emprego em um banco. Mas não conseguiu. Mais tarde, ficou irada porque Eliot se tornou editor de uma casa rival, The Criterion.

Em 1919, Virginia publica “Noite e Dia”. A crítica não gostou. E.M. Forster (1879-1970) e Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923) odiaram. Mas Forster, amigo, foi elegante e discreto. Disse que o livro não era melhor que “The Voyage Out”. (Forster mais tarde ficou chateado com algumas críticas ferinas de Virginia.) Mansfield foi dura: “Noite e Dia” era “uma mentira da alma. Falando sobre esnobismo intelectual — o livro dela fede a isso. (Mas não posso dizê-lo.) É muito longo e cansativo”. Virginia, que não sabia assimilar criticas, ficou abalada.

Mas Virginia se curava dos petardos da crítica de um modo extraordinário: no lugar de ficar bloqueada, produzia mais, e melhor. Se o romance anterior fosse considerado ruim, até pelos amigos que adorava, como Forster, procurava escrever outro melhor, mais inventivo. Foi o que ocorreu depois de “Noite e Dia”. Em 1922, publicou pela Hogarth Press “O Quarto de Jacob”. T.S. Eliot festejou: “Você se libertou de qualquer compromisso com o romance tradicional e seu talento original. Parece-me que construiu uma ponte sobre certa lacuna que existia entre seus outros romances e a prosa experimental de ‘Monday or tuesday’, conseguindo um sucesso notável”.

“O Quarto de Jacob”, para Quentin Bell, marca o inicio de sua maturidade e fama. Em 1925 Virginia publicou “Mrs. Dalloway”, que agradou à crítica. Forster elogiou “Mrs. Dolloway”. Thomas Hardy leu “The Commom Reader” com prazer. Virginia ficou maravilhada.

Entre 1925 e 1928, Virginia lança “Passeio ao Farol” e concebe “As Ondas”. Nesse período ela conhece Vita, a sua grande paixão. Vita era lésbica, mas casada, como Virginia. Quentin Bell é discreto e diz pouco sobre o assunto. Tudo indica que as duas não chegaram a ter um caso no sentido moderníssimo. Vita escreveu para Virginia: Você gosta mais das pessoas pelo cérebro do que pelo coração. Fosse hoje, o texto de Vita teria acréscimo: Você gosta mais das pessoas pelo cérebro do que pelo coração e pelo corpo.

Na verdade, Virginia era de uma carência extremada e todo mundo que lhe dava atenção recebia alguma esperança, de sexo ou afeto. Só que, afeto, tudo bem, sexo, nada. Pelo menos, a se acreditar na versão do sobrinho.

Quem leu “Orlando” sabe que Vita é Orlando. Para Quentin Bell, Orlando é o único dos romances de Virginia que se aproxima da emoção sexual, ou antes, homossexual; pois, enquanto o herói/heroína sofre uma transformação física, sendo no começo um esplêndido jovem e depois uma linda dama, a metamorfose psicológica é muito menos completa. O livro vendeu bem. Mas Orlando, sabia Virginia, não era um grande livro. Julgamento que os leitores de hoje não partilham, sobretudo por que as questões sexuais se tornaram mais importantes, na avaliação do romance, do que as literárias.

Em 1931, Virginia, a mulher que adorava charutos, publica “As Ondas”, para os críticos, sua obra-prima. Leonard Woolf, que sempre opinava, criticamente, sobre os livros de Virginia, disse: O livro é uma obra-prima, a melhor das suas obras. Ela adorou. Leonard era suspeito, até por que conhecia a fragilidade emocional de Virginia, mas era, ao mesmo tempo, prudente, justo e rigoroso.

O indefectível E. M. Forster escreveu que encontrara um clássico. A opinião dele era muito respeitada por Virginia. Um tinha inveja do outro. Mas, éticos, respeitavam as diferenças entre suas obras. Virginia gostava de conversar sobre homossexualismo com Forster, que adorava rapazes.

Virginia não gostava da crítica acadêmica, que achava estéril. Talvez fosse uma vingança por não ter obtido educação universitária. Talvez fosse pela percepção de que, como denuncia Gore Vidal, muitos teóricos da literatura querem substituir a literatura pela teoria literária.

Quentin Bell registra um aspecto curioso: Virginia adorava mexericos, fofoca, e dizia o que pensava, não importando as consequências. Outra coisa curiosa: como Joyce e outras, ela aproveitou a história de sua família e as relações com os amigos nos seus romances. Vida e obra, estetizadas, estão ligadíssimas e indissociáveis em Virginia. Mas é óbvio que a escritora não escreve biografias literárias e, claro, tinha uma imaginação poderosa.

Na década de 30, alguns críticos atacam Virginia, deixando-a desequilibrada emocionalmente. O mais virulento, Wyndham Lewis, escreve: Ela é sobremodo insignificante. Ninguém mais a leva a sério. Os críticos de esquerda não atacavam Virginia. Stephen Spender e Cecil Day-Lewis (pai de Daniel Day-Lewis, ator de “A Insustentável Leveza do Ser” e “Meu Pé Esquerdo”) gostavam de sua obra.

Em 1937, Virgínia pública “Os Anos” e sente a loucura chegando. Leonard achou o livro ruim, mas ficou calado, ou melhor, temendo que Virginia se matasse, mentiu: Acho que é extraordinariamente bom. Virginia sabia que o livro era ruim. O economista Keynes gostou do livro, de forma irrestrita. Em 1939, Virginia foi ver Freud, que estava exilado em Londres. Ele teria impressionado Virginia como um homem alerta. Mas torto, encarquilhado muito velho e a velha chama agora bruxuleante. Freud disse a Virginia e Leonard que seria necessária uma geração para eliminar aquele veneno [o nazismo de Hitler].

Por causa da Segunda Guerra Mundial, Leonard e Virginia Woolf chegaram a pensar em suicídio. Obtiveram até uma dose letal de morfina. Mas, com Londres bombardeada, Virginia deixou de falar em suicídio. Numa carta a Ethel Smyth, escreveu: … o que tocou e na verdade feriu o meu coração em Londres [durante os bombardeios dos nazistas] foi aquela velha mulher, suja de fuligem nos aposentos dos fundos, preparando-se, depois de um ataque aéreo, para enfrentar o próximo… E também a paixão da minha vida, a cidade de Londres — ver Londres em escombros, isso também atingiu meu coração.

No início de 1941, Virginia estava desesperada, louca. Mesmo assim tentou convencer a médica Octavia Wilberforce, uma amiga, de que não estava doente mentalmente. Mas confessou partes de seus medos. Medos de que o passado voltaria, de que nunca mais conseguiria escrever.

É triste e pungente como Quentin Bell fala do fim de sua tia escritora: “Na manhã de sexta-feira, 28 de março, um dia claro, luminoso e frio, Virginia foi como de costume ao seu estúdio no jardim. Lá, escreveu duas cartas, uma para Leonard e outra para Vanessa — as duas pessoas que mais amava. Nas duas cartas explicava que vinha ouvindo vozes e acreditava que nunca mais ficaria boa; não podia continuar estragando a vida de Leonard. Ela colocou o bilhete sobre a lareira da sala de estar, e cerca de 11h30 esgueirou-se para fora, levando sua bengala de passeio; e atravessou os prados até o rio. Leonard acreditava que ela já havia feito uma tentativa para se afogar: assim, teria aprendido com o fracasso, e estava decidida a não falhar de novo. Deixando a bengala na margem, ela esforçou-se para pôr uma grande pedra no bolso do casaco. Depois encaminhou-se para a morte, ‘a única experiência’, dissera um dia a Vita, ‘que nunca descreverei’”.

Última carta a Leonard Woolf

Querido, tenho certeza de que estou enlouquecendo de novo. Sinto que não podemos passar por outra daquelas terríveis fases. E desta vez não ficarei curada. Começo a ouvir vozes, e não posso me concentrar. Assim, estou fazendo o que me parece melhor. Você me deu a maior felicidade possível. Não creio que duas pessoas pudessem ser mais felizes até chegar esta doença terrível. Não consigo mais lutar. Sei que estou estragando a sua vida e que sem mim você poderá trabalhar. E você vai, eu sei. Está vendo, nem consigo mais escrever adequadamente.

Não consigo ler. O que quero dizer é que devo a você toda a felicidade da minha vida. Você foi absolutamente paciente comigo e incrivelmente bom. Quero dizer isso — e todo mundo sabe. Se alguém pudesse me salvar, teria sido você. Perdi tudo, menos a certeza da sua bondade. Não posso mais continuar estragando sua vida. Não creio que duas pessoas tenham sido mais felizes do que nós fomos.

Virginia Woolf tentou ‘curar’ sua loucura pelo suicídio publicado primeiro em https://www.revistabula.com

0 notes

Text

Hey, a tiny fandom general purpose announcement: if you’re thinking about sending me an ask along the lines of “do you think Nightingale shagged/met/was related to [historical figure]”, there is one all-purpose answer I can give you right now: I guess he could have if the timeline matches up, but... *shrugs* I don’t know!

I get these asks now and again (anon who sent me the long one about some guy called Quentin Crisp, who I am entirely unfamiliar with, this was prompted by but is by no means just about you). As I think I’ve said before, as far as Nightingale is concerned I’m pretty happy to see what canon gives us, backstory-wise*. The most interesting thing about him to me is his future, not his past.

But clearly a lot of you have a lot of thoughts about what he got up to prior to the war, so I encourage you to write meta, write fic, headcanon like crazy, start shipping Nightingale/John Maynard Keynes**, whatever works for you! Just know that I don’t really have a lot to contribute here.

*one minor exception: there is no way Nightingale managed to be the generally decent human being he apparently is without interacting with a lot of people who weren’t fellow overprivileged-white-dude Folly members, so if you wanna tell me all about interesting British/Commonwealth-and-Empire non-white, non-dude people in the 1920s-40s he could have hung around with, I would love to know about it! I’m still not going to have specific opinions on what he did, but let’s get some history in here.

**I can’t believe this is now a vaguely canon-adjacent option if you want a historical queer ship for Nightingale but THERE YOU GO

#rivers of london#thomas nightingale#this is just not a thing I think about a lot#nightingale is most interesting to me in relationship to peter#because the not-very-secret of these books is#nightingale is peter's sidekick#meta#the tiny fandom

21 notes

·

View notes

Link

Peter Beard, Wildlife Photographer on the Wild Side, Dies at 82

Called “the last of the adventurers,” Mr. Beard photographed African fauna at great personal risk, and well into old age could party till dawn. He had been missing for 19 days.

By Margalit Fox

Published April 19, 2020 Updated April 20, 2020, 10:01 a.m. ET

Peter Beard, a New York photographer, artist and naturalist to whom the word “wild” was roundly applied, both for his death-defying photographs of African wildlife and for his own much-publicized days — decades, really — as an amorous, bibulous, pharmaceutically inclined man about town, was found dead in the woods on Sunday, almost three weeks after he disappeared from his home in Montauk on the East End of Long Island. He was 82.

His family confirmed that a body found in Camp Hero State Park in Montauk was that of Mr. Beard.

Peter Beard’s Family Confirms His DeathApril 19, 2020

He had dementia and had experienced at least one stroke. He was last seen on March 31, and the authorities had conducted an extensive search for him.

“We are all heartbroken by the confirmation of our beloved Peter’s death,” the family said in a statement, adding, “He died where he lived: in nature.”

Mr. Beard’s best-known work was the book “The End of the Game,” first published in 1965. Comprising his text and photographs, it documented not only the vanishing romance of Africa — a place long prized by Western colonialists for its open savannas and abundant big game — but also the tragedy of the continent’s imperiled wildlife, in particular the elephant.

In later years, Mr. Beard became famous for embellishing his photographic prints with ink and blood — either human (his own) or animal (from a butcher) — yielding complex, cryptic, multilayered surfaces.

He was also known for the idiosyncratic, genre-bending diaries that he had kept since he was a boy — profuse assemblages of words, images and found objects like stones, feathers, train tickets and toenail clippings — and for the large, even more profuse collages to which the diaries later gave wing.

But as renowned as he was for his work (he received solo exhibitions at the International Center of Photography in Manhattan, the Centre National de la Photographie in Paris and elsewhere), Mr. Beard remained at least as well known for his swashbuckling, highly public private life.

Even by the dashing standards of wildlife photography, his résumé was the stuff of high drama, full of daring, danger, romance and tall tales, many of them actually true. Had Mr. Beard not already existed, he might well have been the result of a collaborative brain wave by Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Paul Bowles.

He was matinee-idol handsome and, as an heir to a fortune, wealthy long before his photographs began selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece.

Besides documenting Africa’s vanishing fauna, he photographed some of the world’s most beautiful women in fashion shoots for Vogue, Elle and other magazines. He had well-documented romances with many of them, including Candice Bergen and Lee Radziwill, the sister of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

“The last thing left in nature is the beauty of women, so I’m very happy photographing it,” Mr. Beard told the British newspaper The Observer in 1997.

He discovered one supermodel, Iman, and spun a fabulous legend about her origins. He was married for a time to another, Cheryl Tiegs.

A denizen of Studio 54 in its disco-era heyday, he numbered among his friends the likes of Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, Salvador Dalí, Mrs. Onassis, Grace Jones, the Rolling Stones and Francis Bacon, who painted his portrait more than once.

In 1963 he appeared, nude, in Adolfas Mekas’s avant-garde film “Hallelujah the Hills!,” a critical and popular hit at the inaugural New York Film Festival. He later recalled that “Andy Warhol called it the first streak.”

He seemed to possess the indefatigability of a half-dozen men, and well into old age routinely reveled until dawn, his escapades becoming grist for gossip columnists worldwide.

“Peter Beard — gentleman, socialite, artist, photographer, Lothario, prophet, playboy and fan of recreational drugs — is the last of the adventurers,” The Observer said.

“James Dean grown up,” another British paper, The Evening Standard, called him.

“The hard-partying septuagenarian shutterbug,” The Daily News of New York wrote.

There was the time, for example, as Vanity Fair reported in 1996, that Mr. Beard, after roistering until 5 a.m. at a Nairobi nightclub, emerged the next afternoon from a tent on his ranch in the Kenyan countryside followed by the “four or five” young Ethiopian women he had brought home with him.

“We were very cozy,” he noted.

There was the time in 2013, The New York Post reported, citing court documents, that Mr. Beard, then 75, returned home about 6 a.m. to the Midtown Manhattan apartment he shared with his wife, Nejma Beard, who was also his agent, after a night’s revels.

Ms. Beard did not take kindly to his return — not because of the hour, but because he happened to have two Russian prostitutes in tow. In response, she dialed 911, declared that her husband was attempting suicide and had him committed for a time to a local hospital.

“Beard doesn’t really make art to enhance life for the rest of us,” a critic for The Globe and Mail of Toronto wrote in 1998. “He has created his flamboyant life as a work of art.”

Yet for all its swashbuckling glitter, Mr. Beard’s curriculum vitae was shot through with darkness. His art, reviewers often remarked, seemed haunted by death and loss. So, at times, did his life. In the 1970s, a devastating fire obliterated his home, along with 20 years’ work. In the 1990s, he was attacked and nearly killed by one of the very animals he had long worked to save

A Black Sheep Son

By his own account the black sheep of an illustrious family, Peter Hill Beard was born in Manhattan on Jan. 22, 1938, to Anson McCook Beard and Roseanne (Hoar) Beard.

A great-grandfather, James J. Hill, known in the press as “the Empire Builder,” founded the Great Northern Railway — running from St. Paul to Seattle — in the mid-19th century. A stepgrandfather was the tobacco magnate Pierre Lorillard V.

Peter’s father was a partner at Delafield & Delafield, a Wall Street brokerage house; his mother, Mr. Beard said long afterward, “suffered from lack of education and the disease of conformity.”

After spending part of his childhood in Alabama, where his father was stationed with the Army Air Forces, Peter was reared on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and Long Island. He began taking photographs as a child, with a Voigtländer bellows camera given to him by a grandmother. He also began keeping the eclectic diaries that would become a professional hallmark.

Yet his obvious artistic gifts, he later said, were lost on his parents.

“Nobody said, ‘Your pictures are good’ or ‘You have a good eye,’” Mr. Beard told the CBS News program “Public Eye” in 1998. What they said, he continued, was: “‘Good hobby. When are you going to do something worthwhile?’”

His future seemed foreordained. He was dispatched to the schools his father had attended, including the Buckley School in New York and Pomfret School in Connecticut.

In 1955, at 17, Peter made his first trip to Africa, in the company of Quentin Keynes, a great-grandson of Charles Darwin. Despite being chased up a tree by an angry hippo he was trying to photograph, he was smitten. In Kenya, he was introduced to the last of a generation of big-game hunters and went shooting — in both senses — with them.

Entering Yale, he embarked on premedical studies but quickly changed course.

“It soon became painfully clear,” Mr. Beard later said, “that human beings were the disease.” He switched to art history, studying with the artist Josef Albers and the art historian Vincent Scully.

He returned to Kenya the summer after his junior year. Many of the photographs he took then would be reproduced in “The End of the Game.”

After graduating from Yale in 1961, he signed on, per his parents’ wishes, as a trainee with the advertising agency J. Walter Thompson. But the gray-flanneled life was not for him, and he soon defected.

Traveling to Denmark, he met and photographed Karen Blixen, who, under the pen name Isak Dinesen had written the 1937 memoir “Out of Africa,” a book Mr. Beard cited as a deep influence. He later bought 45 acres in the countryside outside Nairobi, abutting the coffee farm on which Ms. Blixen had lived.

“The End of the Game,” originally published by Viking Press, made Mr. Beard’s reputation. While a few reviewers took him to task for his seemingly uncritical embrace of the romance of the great white hunter, most praised his dynamic photographs and arresting thesis: that the game preserves meant to safeguard elephants were unintentionally contributing to their destruction.

Reviewing the volume in The New York Times Book Review in 1965, J. Anthony Lukas wrote:

“The portraits of the animals themselves — alive, dying and dead — are superb. These are not ‘pretty’ Walt Disney shots of gazelles leaping through the meadows or parrots chattering in the jungle greenery. Beard’s pictures catch all the saw-toothed savagery of the animals who must show each day that they are fit to survive.”

Mr. Beard’s close studies of wildlife at Tsavo East National Park in Kenya had shown him that the elephant population there, having far outstripped the available food supply, was starving to death by the thousands. Deeming himself a “preservationist,” he argued for the controlled culling of elephant herds, a position that by the 1960s had made many conservationists cringe.

“Conservation,” Mr. Beard once said, “is for guilty people on Park Avenue with poodles and Pekingeses.”

Mr. Beard brought his thesis home even more starkly in subsequent editions of “The End of the Game,” which contained his later aerial photographs of the ravaged Kenyan landscape. In those images, elephant skeletons litter the parched earth like gleaming ghosts.

Ever-Beckoning Kenya

Though Mr. Beard maintained homes in Manhattan and Montauk, he lived and worked in Kenya for long periods. In the mid-1970s, walking down a Nairobi street, he spotted Iman. He introduced her to Wilhelmina Models, the New York agency, and her career was born.

Presenting Iman to the American news media, Mr. Beard gleefully spun an imperial fantasy: that he had come upon her herding cattle in the African bush. In truth, as Iman soon pointed out with what can reasonably be interpreted as a mixture of amusement and irritation, she spoke five languages, had been a political science student at the University of Nairobi and was the daughter of a Somali diplomat.

Mr. Beard’s first marriage, to Minnie Cushing, the daughter of a distinguished Newport, R.I., family, ended in divorce, as did his second, to Ms. Tiegs, to whom he was married in the 1980s. He married Nejma Khanum, the daughter of an Afghan diplomat, in 1986.

For Mr. Beard, the late 20th century was a notably dark time. In 1977, while he was in New York City, an oil furnace exploded at his Montauk home. The house was destroyed, along with paintings by Warhol, Bacon and Picasso and decades’ worth of Mr. Beard’s photographs and diaries.

In September 1996, while picnicking near the Kenya-Tanzania border, he was charged by an elephant, who came at him, he recalled, like “a freight train.”

The elephant ran a tusk through his leg, narrowly missing the femoral artery. Using its head as a battering ram, it crushed Mr. Beard, breaking ribs and fracturing his pelvis in at least a half-dozen places. By the time he arrived at the hospital in Nairobi, according to news reports, he had no pulse.

Doctors revived him, but damage to his optic nerve left him blind. He was told that he might never walk again. He eventually regained his sight, and the ability to walk. He underwent further surgery in New York and lived ever after with more than two-dozen pins in his pelvis.

Nejma Beard filed for divorce in the mid-90s, but the couple reconciled after the attack and remained married.

Besides his wife, he is survived by a daughter, Zara; a granddaughter, and his brothers, Anson Jr. and Samuel.

Among his other books are “Eyelids of Morning” (with Alistair Graham), about crocodiles; “Peter Beard,” a vast compendium of his work; and “Zara’s Tales: Perilous Escapades in Equatorial Africa.”

As Mr. Beard aged, the opinions he voiced freely in interviews sounded increasingly out of step with 21st-century sensibilities. He seemed, to all appearances, to be marooned in the world of the dinner jacket and the great white hunter — a world he simultaneously abhorred and pined for — as the new century passed him by.

In an interview with New York magazine in 2003, for instance, he expressed surprise on being told that the fashion designer Tom Ford was gay.

“But he looks absolutely normal,” Mr. Beard protested, going on to say, “I’m not homophobic,” and to assert that Truman Capote “was one of my best friends.”

Speaking in the same interview about why he had decided to forsake Africa after four decades, Mr. Beard said, “Africans are the only racists I know,” adding, “and that’s because they’re primitive.”

In the end, which Peter Beard will be remembered — the artist or the hedonist — is an open question. Perhaps, as he was clearly aware, those two incarnations need not be mutually exclusive.

In “Zara’s Tales,” written for his daughter, he quotes a line from “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” a late-18th-century work by William Blake, that seemed to have been a touchstone for both his life and his art: “You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.”

To those emblematic words, Mr. Beard appended a personal capstone. “If you crave something new, something original, particularly when they keep saying, ‘Less is more,’” he wrote, “remember that I say: Too much is really just fine.”

Stacey Stowe contributed reporting.

Margalit Fox is a former senior writer on the obituaries desk at The Times. She was previously an editor at the Book Review. She has written the send-offs of some of the best-known cultural figures of our era, including Betty Friedan, Maya Angelou and Seamus Heaney.

0 notes

Link

Photographer Peter Beard, world-renown for his beautiful and intimate images of Africa and African wildlife, was found dead at age 82 after he went missing from his Montauk, New York, home on April 1.

On Sunday, nearly three weeks after his disappearance, his family confirmed Beard’s death in a statement shared on social media. “We are all heartbroken by the confirmation of our beloved Peter’s death. We want to express our deep gratitude to the East Hampton police and all who aided them in their search, and also to thank the many friends of Peter and our family who have sent messages of love and support during these dark days,” the statement read.

“Peter was an extraordinary man who led an exceptional life. He lived life to the fullest; he squeezed every drop out of every day. He was relentless in his passion for nature, unvarnished and unsentimental but utterly authentic always. He was an intrepid explorer, unfailingly generous, charismatic, and discerning,” the statement continued.

“Peter defined what it means to be open: open to new ideas, new encounters, new people, new ways of living and being. Always insatiably curious, he pursued his passions without restraints and perceived reality through a unique lens. Anyone who spent time in his company was swept up by his enthusiasm and his energy. He was a pioneering contemporary artist who was decades ahead of his time in his efforts to sound the alarm about environmental damage. His visual acuity and elemental understanding of the natural environment was fostered by his long stays in the bush and the ‘wild-deer-ness’ he loved and defended. He died where he lived: in nature. We will miss him every day,” the statement concluded.

The East Hampton Town Police said on Sunday that authorities located “the remains of an elderly male consistent with the physical and clothing description of Mr. Beard” in Camp Hero State Park in Montauk, according to a statement obtained by the New York Daily News. The remains are still awaiting identification.

View this post on Instagram #peterbeardart #peterbeard

A post shared by Peter Beard (@peterbeardart) on Apr 19, 2020 at 5:02pm PDT

//www.instagram.com/embed.js

In the hours after Beard was reported missing, police were concerned Beard could be in immediate need of medical attention due to his battle with dementia — a disease of the brain that affects memory loss and judgment. Dozens of police and firefighters participated in the research, using dogs, drones and thermal imaging equipment, the New York Times reported.

At the time, Beard’s wife, Nejma Beard, did not immediately return PEOPLE’s request for comment. The couple and daughter Zara split their time between Montauk, New York City and Kenya, according to Beard’s website.

For more than half his life, Beard dedicated himself to documenting life in Africa, from its people to its animals, spurred on by a need to shine a lot on the continent.

“The wilderness is gone,” the artist was quoting saying by Vanity Fair in 1996, “and with it much more than we can appreciate or predict. We’ll suffer for it.”

Beard — born in New York in January 1938 — became enamored with nature during trips to Tuxedo Park with his grandmother, who gave him his first camera, a biography on his website reads. At age 17, Beard traveled to Africa to work on a film documenting rhinos with Quentin Keynes, the great-grandson of Charles Darwin.

RELATED: Famed Photographer Peter Beard Reported Missing from His Hamptons Home

Though he enrolled in Yale to study medicine, he quickly switched his concentration to art, a decision that would eventually lead him back to Africa.

Returning to the continent would be life-changing, and after receiving a special provision to live on a ranch and document Africa’s people and wilderness, he would publish The End of the Game in 1965. Twelve years later, he would republish the book to include photographs documenting the deaths of thousands of elephants and rhinos from starvation and stress Kenya’s Tsavo National Park.

Beard’s adventures on the continent also led him to a chance encounter with a young woman on the streets of Nairobi, Kenya. Beard asked and paid to take her picture, and the woman, Zara Mohamed Abdulmajid — better known today as Iman — would go on to become one of the world’s most famous supermodels.

Beard opened his first exhibition in 1975 at the Blum Helman Gallery in New York, which was followed by a one-man exhibition in 1977 at the International Center of Photography.

“I think of them like an accumulation of petty and futile memories put down on paper, collaged, photographed, and worked on,” Beard told the New York Times of his work in 1997.

His most recent display was at the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, New York, in 2016, according to his website.

During his career, Beard befriended many renowned celebrities of their time, including Andy Warhol, Francis Bacon, Salvador Dali, Richard Lindner, Terry Southern and Truman Capote.

In the ‘90s, Beard was famously trampled and speared in the leg by an elephant while photographing a heard on the Tanzanian border.

from PEOPLE.com https://ift.tt/2Km8aAc

0 notes

Photo

Libri in tv

La tua settimana letteraria a portata di telecomando.

Lunedì 17 settembre 2018

Diario di una schiappa (ore 20:25 – Boing)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 2010 | REGIA: Thor Freudenthal

Tratto dal romanzo illustrato omonimo di Jeff Kinney.

Dal tramonto all'alba (ore 21:10 - Paramount Channel)

GENERE: Horror | ANNO: 1996 | REGIA: Robert Rodriguez

Tratto da un racconto di Robert Kuzman.

Insider - Dietro la verità (ore 23:28 – Iris)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1999 | REGIA: Michael Mann

Ispirato all'articolo "The Man who Knew Too Much" di Marie Brenner, pubblicato su Vanity Fair.

Martedì 18 settembre 2018

Venere in visone (ore 7:50 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1960 | REGIA: Daniel Mann

Tratto dal romanzo 'Butterfield 8' di John O' Hara.

La bisbetica domata (ore 9:55 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1967 | REGIA: Franco Zeffirelli

Tratto dall'omonima commedia di William Shakespeare.

Sandokan alla riscossa (ore 11:20 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Avventura | ANNO: 1964 | REGIA: Luigi Capuano

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Emilio Salgari.

Tre colonne in cronaca (ore 12:53 – Iris)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1989 | REGIA: Carlo Vanzina

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Corrado Augias.

Torna El Grinta (ore 16:34 - Rete 4)

GENERE: Western | ANNO: 1975 | REGIA: Stuart Millar

Tratto dal romanzo "Il Grinta" di Charles Portis.

I giorni dell'ira (ore 21:00 – Iris)

GENERE: Western | ANNO: 1967 | REGIA: Tonino Valerii

Tratto dal romanzo "Der Tod ritt Dienstags" di Ron Barker.

La ciociara (ore 21:05 - Tv 2000)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1960 | REGIA: Vittorio De Sica

Tratto dal romanzo omonimo di Alberto Moravia.

I Love Shopping (ore 21:10 - Paramount Channel)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 2008 | REGIA: P.J. Hogan

Tratto dal romanzo "I love shopping", con elementi di “I love shopping a New York”, rispettivamente primo e secondo romanzo della serie “I love shopping” di Sophie Kinsella.

Beyond (ore 21:15 - Rai 5)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 2011 | REGIA: Pernilla August

Tratto dall'omonimo romanzo dell'autrice svedese-finlandese Susanna Alakoski.

Jumanji (ore 21:25 – Nove)

GENERE: Fantasy | ANNO: 1995 | REGIA: Joe Johnston

Liberamente ispirato al romanzo "Jumanji" di Chris Van Allsburg.

Qualcuno come te (ore 23:00 - Paramount Channel)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 2001 | REGIA: Tony Goldwyn

Tratto dal romanzo "Animal Husbandry", opera prima di Laura Zigman.

L'ultimo dei mohicani (ore 23:30 – Spike)

GENERE: Avventura | ANNO: 1992 | REGIA: Michael Mann

Liberamente tratto dal romanzo omonimo di James Fenimore.

Mercoledì 19 settembre 2018

Cartagine in fiamme (ore 8:45 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Avventura | ANNO: 1959 | REGIA: Carmine Gallone

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Emilio Salgari.

California (ore 15:35 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Western | ANNO: 1977 | REGIA: Michele Lupo

Tratto dall’omonimo racconto di Roberto Leoni e Franco Bucceri.

Harry Potter e la Pietra Filosofale (ore 21:20 - Italia 1)

GENERE: Fantasy | ANNO: 2001 | REGIA: Chris Columbus

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di J. K. Rowling.

I miserabili (ore 23:25 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1998 | REGIA: Bille August

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Victor Hugo.

Giovedì 20 settembre 2018

Il cappotto di Astrakan (ore 6:25 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1979 | REGIA: Marco Vicario

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo Pietro Chiara.

La bisbetica domata (ore 7:35 - Cine Sony))

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1967 | REGIA: Franco Zeffirelli

Tratto dall'omonima commedia di William Shakespeare.

Sole rosso (ore 12:00 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Western | ANNO: 1971 | REGIA: Terence Young

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Laird Koenig.

Uragano (ore 16:37 - Rete 4)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1979 | REGIA: Jan Troell

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di James Norman Hall e Charles Nordhoff.

Ispettore Callaghan: il caso Scorpio è tuo! (ore 21:00 - Iris)

GENERE: Poliziesco | ANNO: 1971 | REGIA: Don Siegel

Tratto dall’omonimo racconto di Harry Julian Fink e Rita M. Fink.

Twilight (ore 21:10 - La5)

GENERE: Fantasy | ANNO: 2008 | REGIA: Catherine Hardwicke

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Stephenie Meyer.

Io, Robot (ore 21:15 - Focus)

GENERE: Fantascienza | ANNO: 2004 | REGIA: Alex Proyas

Ispirato ai racconti di Isaac Asimov.

Il bambino con il pigiama a righe (ore 21:25 - Nove)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 2008 | REGIA: Mark Herman

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di John Boyne.

Sex and the City (ore 23:00 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 2008 | REGIA: Michael Patrick King

Liberamente ispirato al romanzo omonimo di Candace Bushnell.

L'Attenzione (ore 23:30 - Cielo)

GENERE: Erotico | ANNO: 1985 | REGIA: Giovanni Soldati

Liberamente ispirato al romanzo omonimo di Alberto Moravia.

Creation (ore 0:50 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Biografico | ANNO: 2009 | REGIA: Jon Amiel

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Randal Keynes.

Venerdì 21 settembre 2018

Perdutamente tua (ore 8:15 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1942 | REGIA: Irving Rapper

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Olive Higgins Prouty.

Quel maledetto ponte sull’Elba (ore 10:20 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Guerra | ANNO: 1968 | REGIA: León Klimovsky

Tratto dall’omonimo racconto di Lou Carrigan.

Dagli Appennini alle Ande (ore 11:13 - Iris)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1959 | REGIA: Folco Quilici

Tratto dall’omonimo racconto di Edmondo De Amicis, in Cuore.

Gli uomini dal passo pesante (ore 15:45 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Western | ANNO: 1965 | REGIA: Mario Sequi, Alfredo Antonini

Tratto dal racconto "Guns of North Texas" di Will Cook.

Delitto sotto il sole (ore 16:19 - Rete 4)

GENERE: Giallo | ANNO: 1982 | REGIA: Guy Hamilton

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Agatha Christie.

Il dottor Dolittle (ore 21:10 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1997 | REGIA: Betty Thomas

Tratto dal racconto "Doctor dolittle stories" di Hugh Lofting.

Ancora vivo (ore 21:25 - Nove)

GENERE: Azione | ANNO: 1996 | REGIA: Walter Hill

Tratto dall’omonimo racconto di Ryuzo Kikushima e Akira Kurosawa.

Camere da letto (ore 0:40 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1997 | REGIA: Simona Izzo

Tratto dall’omonimo racconto di Graziano Diana e Simona Izzo.

Sabato 22 settembre 2018

Il sorpasso (ore 7:00 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1962 | REGIA: Dino Risi

Tratto dall’omonimo racconto di Rodolfo Sonego.

Tempo d'estate (ore 9:55 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Sentimentale | ANNO: 1955 | REGIA: David Lean

Tratto dal romanzo "The time of the cuckoo" di Arthur Laurents.

Quell'ultimo ponte (ore 11:35 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Guerra | ANNO: 1977 | REGIA: Richard Attenborough

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Cornelius Ryan.

Sognando l'Africa (ore 13:20 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 2000 | REGIA: Hugh Hudson

Tratto dal romanzo "Sognavo l'Africa" di Kuki Gallmann.

Twilight (ore 13:50 - La5)

GENERE: Fantasy | ANNO: 2008 | REGIA: Catherine Hardwicke

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Stephenie Meyer.

Io, Robot (ore 15:10 - Focus)

GENERE: Fantascienza | ANNO: 2004 | REGIA: Alex Proyas

Ispirato ai racconti di Isaac Asimov.

Il club di Jane Austen (ore 15:30 - Cine Sony)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 2007 | REGIA: Robin Swicord

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Karen Joy Fowler.

Il dottor Dolittle (ore 15:45 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1997 | REGIA: Betty Thomas

Tratto dal racconto "Doctor dolittle stories" di Hugh Lofting.

Jumanji (ore 17:00 - Nove)

GENERE: Fantasy | ANNO: 1995 | REGIA: Joe Johnston

Liberamente ispirato al romanzo "Jumanji" di Chris Van Allsburg.

K-PAX - Da un altro mondo (ore 17:15 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 2001 | REGIA: Iain Softley

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Gene Brewer.

I Love Shopping (ore 19:10 - Paramount Channel)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 2008 | REGIA: P.J. Hogan

Tratto dal romanzo "I love shopping", con elementi di “I love shopping a New York”, rispettivamente primo e secondo romanzo della serie “I love shopping” di Sophie Kinsella.

La sindrome di Stendhal (ore 21:10 - Italia 2)

GENERE: Horror | ANNO: 1996 | REGIA: Dario Argento

Ispirato dal libro omonimo di Graziella Magherini.

Detective coi tacchi a spillo (ore 21:30 - LA7D)

GENERE: Poliziesco | ANNO: 1991 | REGIA: Jeff Kanew

Basato sui romanzi di Sara Paretsky su V. I. Warshawski.

In the Electric Mist - L'occhio del ciclone (ore 22:55 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Thriller | ANNO: 2009 | REGIA: Bertrand Tavernier

Tratto dal romanzo "In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead" di James Lee Burke.

Tre scapoli e un bebè (ore 23:15 - LA7D)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1987 | REGIA: Leonard Nimoy

Tratto dal racconto "Tre uomini e una culla" di Coline Serreau.

Jackie Brown (ore 23:30 - Nove)

GENERE: Noir | ANNO: 1997 | REGIA: Quentin Tarantino

Tratto dal romanzo "Rum Punch" di Elmore Leonard.

The Divergent Series: Insurgent (ore 0:35 - 20)

GENERE: Fantascienza | ANNO: 2015 | REGIA: Robert Schwentke

Tratto dal romanzo omonimo di Veronica Roth, secondo della trilogia (anche filmica) “Divergent”.

Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky (ore 0:55 - Rai Movie)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 2009 | REGIA: Jan Kounen

Tratto dal romanzo omonimo di Chris Greenhalgh.

Domenica 23 settembre 2018

Don Camillo (ore 11:20 - Tv 2000)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 1952 | REGIA: Julien Duvivier

Tratto dai racconti del volume "Mondo piccolo" (1948) di Giovanni Guareschi.

Io ti salverò (ore 14:40 - La7)

GENERE: Giallo | ANNO: 1945 | REGIA: Alfred Hitchcock

Tratto dal romanzo "The house of Dr. Edwardes", scritto da John Palmer e Hilary A. Saunders, sotto lo pseudonimo di "Francis Beeding”.

Il dottor Dolittle 2 (ore 15:10 – Paramount Channel)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 2001 | REGIA: Steve Carr

Tratto dal racconto "Doctor Dolittle stories" di Hugh Lofting.

Jumanji (ore 16:30 - Nove)

GENERE: Fantasy | ANNO: 1995 | REGIA: Joe Johnston

Liberamente ispirato al romanzo "Jumanji" di Chris Van Allsburg.

I Love Shopping (ore 17:10 - Paramount Channel)

GENERE: Commedia | ANNO: 2008 | REGIA: P.J. Hogan

Tratto dal romanzo "I love shopping", con elementi di “I love shopping a New York”, rispettivamente primo e secondo romanzo della serie “I love shopping” di Sophie Kinsella.

Io prima di te (ore 19:10 - Paramount Channel)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 2016 | REGIA: Thea Sharrock

Tratto dall'omonimo romanzo di Jojo Moyes.

Le amiche (ore 21:15 - Rai Storia)

GENERE: Drammatico | ANNO: 1955 | REGIA: Michelangelo Antonioni

Tratto dal racconto "Tra donne sole" (contenuto in "La bella estate") di Cesare Pavese.

Edge of Tomorrow - Senza domani (ore 21:20 - Italia 1)

GENERE: Fantascienza | ANNO: 2014 | REGIA: Doug Liman

Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Hiroshi Sakurazaka.

La sindrome di Stendhal (ore 22:45 - Italia 2)

GENERE: Horror | ANNO: 1996 | REGIA: Dario Argento

Ispirato dal libro omonimo di Graziella Magherini.

The Watcher (ore 23:01 – Iris)

GENERE: Thriller | ANNO: 2000 | REGIA: Joe Charbanic

Tratto dall’omonimo racconto di Darcy Meyers e David Elliot.

0 notes

Photo

The famous Peter Beard Peter Beard was born in New york. He was given his first camera at the age of 13. A the age of 17 he went on a life changing trip to Africa. He wentwith Quentin Keynes, the explorer and great grandson of Charles Darwin, working on a film documenting rare wildlife that began with white and black rhinos in Zululand. They then went to Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, and finally ended up in Madagascar. Beard traveled to Copenhagen to be meetKaren Blixen, the author of Out Of Africa (1937). Beard then bought a property in Kenya right next to Blixen, and near the Ngong Hills. It was during this time that he worked at Kenya’s Tsavo National Park, documenting and photographing the ensuing distortion of balance that took place in nature between the people, the land, and the animals for his book, The End of the Game (1965). Beard’s first exhibition opened at Blum Helman Gallery, New York. Hi exhibiton included photographs, paintings, burned diaries, taxidermy, African artifacts, and books, amongst other things. Peter Beards work concsits of collage and his daires show his experiences in africa. Peterbeard.com.(2017). The Artist – Peter Beard Studio. [online] Available at: http://peterbeard.com/the-artist/ [Accessed 13 Mar. 2017].