#Obscure Posthuman Species

Text

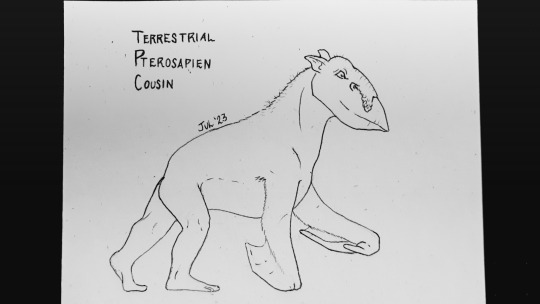

My entry for the Obscure Posthuman Species Contest, a terrestrial Pterosapien relative. There are numerous posthuman lineages that supplement their representative's stories. I picked one of a dozen that doesn't even have pictures, and that creative freedom was one of the

While the Killer Folk are known for eating another posthuman species, they weren't the only ones to hunt and farm for them. Pterosapiens have farmed their large, terrestrial relatives.

This stout terrestrial ptero is a domesticated variety of terry for a lack of concrete terms. They are characterized by their stout body plan, large/deep chest, plantigrade feet, vestigial wing fingers, nonexistent tail, and a snood-like structure on their faces.

Domestic terries look like a turkey, horse, and primate walked into a bar, quite literally in the variety noted for sporting a cartoonish lump on its head. This breed's eyes have a frowny quality deemed adorable by some demographics, and their agreeable nature secures a spot among the few kept as pets, spared from the life of breeding stock or early slaughter for food.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A New Call of the Wild: For a Political Ecology of the Unconstructible - Fréderic Neyrat (2019)

First published on Mediapart, July 2016. Translated by Ill Will Editions.

"What kind of future do we want? The one in which we are forever confined to a planet until the final extinction, however far in the future this event may be, or do we want to be a multi-planetary species?" This question is not asked by a science fiction writer, but by Elon Musk, Silicon Valley's rising star, in January 2016 [1]. ‘Rising star’ is certainly an appropriate metaphor to describe the man who runs SpaceX, a US-based company specializing in astronautics and space flight. Musk prophesies the colonization of Mars in 2025: on this rescue planet, we will build an "autarkic city," and the human species, saved from the end of the world, will then be able to jump star-to-star, spreading new Silicon Valleys here and there, a galactic capitalism nourished by the energy abundance of the universe.

But SpaceX's space wings, like those of its rivals, are struggling to take off; they sometimes explode, like Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo in 2014. In reality, interstellar colonization is a technologically challenging project, anything but a pleasure ride. What awaits future explorers is not a Garden full of wonderful Natives to plunder and slaughter, but the nothingness of lifeless worlds. Moreover, human bodies are more suited to the conditions of life on Earth, and struggle to cross the interstellar void. Our organic makeup is not that of an underwater diver,; we are a life-form in relation to our environment. Far from being a simple external environment, the environment constitutes our interiority, we ingest it and inhale it until our last breath. It is the discourse of ecology that has helped us understand that we are interrelated, dependent, much closer to "compost" than the "posthuman", as the North American theorist Donna Haraway says. Contrary to those who fantasize about extraterrestriality, our motto seems to be obvious: “Return to Earth!" Instead of having our heads in the stars, let us have our feet on the ground, and let us recognize that we are beings who, fundamentally, belong to a territory.

Belongings [appartenances], Earth, and territories are the practical foundations of an ecological thought that pits itself against the extra-territorial imaginary of astro-capitalists who seek to deny and transcend their environmental finitude. As such, every true ecologist is on the side of the struggle at Zone à Défendre [ZAD] in Notre-Dame-des-Landes against the proposed airport project, this dart thrower of ecocidal socialism.

Yet we all know that the extreme right also seeks to "defend" territories and their "identity" from foreigners, refugees and nomads. If we wish to avoid assuming the posture of a mere defensive shield, territorial thinking must recognize that no individual in the world can be reduced to any kind of belonging: each individual is always more than his or her assigned identity (whether national or sexual). We are always more than the sum of our ties. This excess over all identity is not only reserved for human beings, it refers to the that share of wildness [la part sauvage] that every living being carries within itself. This wildness defies geocapitalism, and the Anthropocene economy that promises to "save" us from global warming by controlling the climate through the prowess of geo-engineering - all the while inviting us, in the event of misfortune, to colonize another planet. Nothing can contain this share of wildness within us, which challenges the waves of concrete that are constantly pouring into the world, allowing us to survive - as best we can - the disasters of technoscience (Chernobyl). It will certainly prevent incoherent take-offs to Mars, but it will not allow us to simply stay stuck on Earth: if having our heads in the stars is ecologically problematic, harboring an inaccessible star deep inside our being is an indispensable condition of the policy that says no to geocapitalism.

More than a temporarily abandoned or poorly domesticated natural domain, the wild is the uncivilizable by definition, which irremediably deviates from any norm, which escapes any construction or economic appropriation, and declares itself to be ferociously unconstructible. Far from being oriented towards progress and the future, the unconstructible dimension is the affirmation in the present of what is elusive in our lives, the affirmation of an unknown distance at the very heart of our bonds. It is in the name of this unconstructibility, of this bottomless obscurity from which every free act springs, that a political ecology can refuse everything that makes our lives impossible.

***

[1] “Elon Musk: SpaceX wants to send people to Mars by 2025,″ CNN, Jan 30, 2016.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Accordingly, the very imperfection of our realization of reason’s demands doesn’t reveal infidelity in the rule in question (disrobing it as mere theistic baggage to be overridden with natural abundance) but shows that we are acting in accordance with a maxim whose motivating force, qua “formal”, cannot be reduced to the matter-of-factual frequency of its obeyances or transgressions, failures and victories, at certain times. Such dicta have contentfulness—and thus motivating force for action and guidance for decision—above and beyond all such enumeration. Accordingly, “intelligence reasons and acts from time-general and inexhaustible ends, rather than towards them” (I&S 469). This is precisely what Fichte meant when he said his task “must be eternal”. He was not saying that his vocation actually will be eternal, but that its motivations and demands cannot be exhausted by specification of temporal etiologies, spatial vicinities, physiological germlines, or any other such “manifest totality” (I&S 8), no matter how copious or coreferential. And this, ultimately, is why ‘what is rational’ is substrate-agnostic, or, is an endowment and vocation irreducible to the lives, and even the species, that presently uphold it.

It is simply as an unavoidable artefact of the semantic purism of the transcendental (i.e. that there must be non-declarative language for declaration to function, or, ‘all overt description involves covert prescription’) that intellect cannot but orient itself towards such ends as are topic- and time-neutral (inasmuch as all of its core operations presuppose such orienteering). To be a sophont, and to be worthy of the name, is to delaminate oneself from the tyrannies and the immurements of claustrophobic plenitudes. This is the Aufforderung, or summons, that Fichte identified with reasoning. Intelligence’s “actions are not merely responses to particular circumstances, or time-specific means for pursuing ends that are exhausted once fulfilled” (I&S 466); and so, this is why even the most quotidian activities of our everyday judging cannot but be swept up in an “atemporal and atopic” vocation (I&S 468), or, a project from “nowhere and nowhen” (I&S 21). For, as there is no extension without intension, intelligence isn’t the possibility-to-be-more without the possibility-to-be-moreright. And this, by the by, is why orthogonalist angst about potential superintelligences that are quantitative giants, yet axiological dwarfs, are likely overwrought: because “any artificial agency that boasts at the very least the full range of human cognitive-conceptual abilities can have neither indelible norms nor fixed goals—even if it was originally wired to be a paperclip maximizer” (I&S 397). Such soothsaying ‘maximizer’ narratives, whether dramatized by Bostrom’s paperclip orthogonalism or by Land’s exothermic diagonalism, are alike symptoms of plenitudinarianism, or the “flight from intension” that Quine long ago declared, precisely in their shared refusal that certain concepts can be indispensable and legitimating regardless of the maximalism or minimalism of their frequential and factual realization.60

Objectivity implies adjudication; adjudication implies measurement against the good; and, simply, the good entails the better (I&S 399). This demarcates the disequilibration constitutive of sapience, or what Negarestani calls its “transcendental excess” (I&S 483-4), and it is what all philosophical plenitudes attempt to suffocate and smother. Plenitude is work-shy. For this unstable disequilibration entails that intelligence cannot but be interested not merely with surviving but also with thriving, and thriving requires self-incurred selection rather than self-absolving profusion.

It is not in bountiful blindness but only “in limiting or constraining [itself] by the objective” that general intelligence earns its title (I&S 399). Intelligence’s work of parenting itself, of “applying itself to itself” (I&S 51), is therefore revealed as, essentially, the undertaking of generative constraints. By corollary, intelligence makes its possibility intelligible, and thus expedites its long-coming artificialization, “not by immunizing itself against systematic analysis, but by bringing itself under a thoroughgoing process of desanctification” (I&S 456). Such “desanctification”, as the cohort of enlightening, demands, now as it was two centuries ago, that we expunge and outgrow all the residual sanctities, cybergothic as much as theocratic, retained by those who still cling to the nightside of mind. We must exorcise Mr Mystic, and his “LUMINOUS OBSCURE”, once and for all: even when such “darkness visible” is dressed up, in the most futuristic garb, as the “abstract threat” of some “Great Filter” purposed precisely with absolving us of all tenacious thought in advance.61

Indeed, in the end, there is nothing so risibly human as pessimism about post-humanity, nothing so unimaginative as Lovecraftian horror apropos its unimaginability. To employ plenitude, darkly or vibrantly, to attempt to absolve intentionality of accountability is to reduce us from the decision-making creature (uniquely in charge of its fate, and summoned to self-betterment, because it acknowledges the precarities thereof) and to return us to the circumspect immurements either of claustrophobic sense or of over-abundant nonsense. A broad mind, after all, is no substitute for hard work. “Genuine speculation about posthuman intelligence”, Negarestani instead holds, can only begin with the “extensive labour” of choosing what we think is justified and, concordantly, undertaking all the self-incurred accountability involved in such a choice (I&S 117).

This, then, is Intelligence and Spirit’s rejoinder to the Framework of Plenitude and it undergirds its petition for austere Tenacity—in opposition to formicating Tenebrosity—during this “prehistory of intelligence”. For, “[w]hatever [the] future intelligence might be, it will be bound to certain constraints necessary for rendering the world intelligible and acting on what it is intelligible” (I&S 403). That is, as there is no adult without the trials of the child, there is no general intelligence without the precedential history of its realisation, and, therefore, if there are to be any post-human general intellects, they will, whatever their constitution, be bound to remember and recollect us as their veritable past—no matter how imperfectly and impiously we currently live up to this calling. For our imperfection is no inditement against the legitimacy of the task: besides, there is no adult without the tribulations of the child. Accordingly, this is what Negarestani means when he says that “to be human is the only way out of being human” (I&S 60): where “human” here means infantile, inasmuch as we, as animals gripped by reason, cannot but consider ourselves as merely the “prehistory” to rationality, because to be rational is to strive, eternally and inexhaustibly, for the better. And so, just as, in the words of Roy Wood Sellars, “only [the] realism that passes through idealism can hold its ground”, so too is it true that “to be human is the only way out of being human”. These two statements mean the same thing. They both intone that the Child is the Parent of the Geist. And even if the great silence of the cosmic skies—the “Silentium Universi”—is of portentous and even impending significance for us, we cannot but attempt to parent something that will have made us worthy of remembrance.62

0 notes