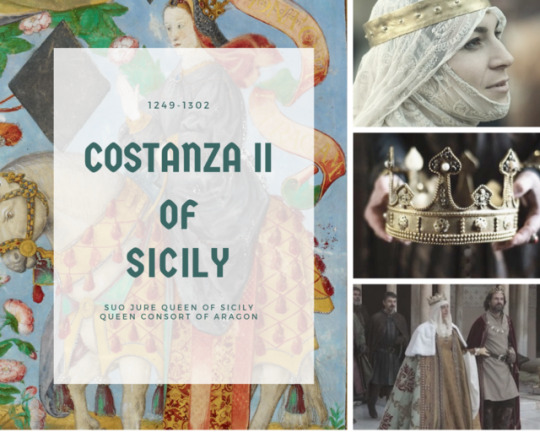

#Norman swabian Sicily

Photo

"I am Manfredi, grandson to the Queen

Costanza: whence I pray thee, when return'd,

To my fair daughter go, the parent glad

Of Aragonia and Sicilia's pride;

And of the truth inform her, if of me

Aught else be told. [...]

Look therefore if thou canst advance my bliss;

Revealing to my good Costanza, how

Thou hast beheld me, and beside the terms

Laid on me of that interdict; for here

By means of those below much profit comes.

Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Purgatory, III, 112-117 & 141-145

Costanza was born around 1249 to Manfredi of Sicily and his first wife Beatrice of Savoy ("et filiam suam Constantiam, quam ex prima consorte sua Beatrice filiam quondam A. Comitis Sabaudiae"). The exact date is unknown, but historian Saba Malaspina attests that when she was born, her grandfather was still alive (“imperatore vivente"). As for the place, it might have been one of the Apulian castles where the Emperor settled down in the last period of his life.

Her wet nurse was Bella d’Amico, mother of admiral Roger of Lauria. Bella, while she was alive, never parted from Costanza, acting like a mother and confidante, especially since Beatrice of Savoy, Manfredi’s first wife, had died when her daughter was just months old.

Nothing is known about Costanza’s childhood. She’s first mentioned when Berthold von Hohenburg asked for her hand on behalf of his nephew Januarius, son of his brother Diepold VIII. Berthold had married Isotta Lancia, cousin of Manfredi’s mother Bianca, and certainly intended to deepen his relationship with the Hohenstaufen’s family. Manfredi, on the other hand, was strenghtening his position (to the point he would be crowned on August 1258 King of Sicily, despite the true heir, his nephew Corradino was still very much alive, although far away in Germany) and so he could afford to reject this marriage proposal.

From a princess of low importance (despite the pretentious name which honored her great-grandmother Costanza I), Costanza soon became a valuable asset and, until Manfredi’s second marriage to Epirote princess Elena Angelina Doukaina, her father’s heir. The Sicilian King then started looking for an important match for his daughter, and ended up selecting Peter, son of Aragonese King James I.

Marriage agreements required that Manfredi supplied his daughter of a dowry of 50000 golden ounces (worth in gold, silver and jewels). On the other hand, the Aragonese crown committed to return the dowry to her family if Costanza were to die without heirs. She would also act as regent for her children (until they were 20 years old) in case Peter were to die before her. In addition, the Sicilian princess was given personal ownership of the city of Girona and the castle of Cotlliure.

Still, the future union presented some problems. First of all, that 50000 golden ounces dowry was indeed a large amount. Manfredi had an hard time collecting it (he had to increase taxes and that spread discontent among the population) and a lot of time passed before the Aragonese crown could collect it (alongside with the bride). The Papacy was obviously against this marriage, and Urban IV asked James I to give up to this union to avoid disgracing his House. Furthermore, in order to save the plans of the future marriage between his daughter Isabella and the heir to the French throne, James had to promise King Louis IX to not support Manfredi in his fight against the Papacy, as well as not helping Provençal rebel Bonifaci VI de Castellana against Charles of Anjou (the King’s younger brother).

Despite all the external pressure, James didn’t give up to the Sicilian match and on July 13th 1262, Peter and Costanza got married in the church of Notre-Dame des Tables (Montpellier). The difference between the lavish Hohenstaufen court and the more simple Aragonese one was huge (“And the said King Manfred lived more magnificently that any lord in the world, and with greater doings, and with greater expenditure”), but thanks to the accounting records of the time, we know that James and Peter tried their best to meet Costanza’s need, purchasing large amounts of luxury items. Since the incomes deriving from Girona and Cotlliure weren’t enough, she was given an annual pension worthy of 30000 Real de Valencia (a type of billon coin) which also soon wasn’t enough to cover the expenses.

Following the death of Manfredi in the Battle of Tagliacozzo (1266) against Charles of Anjou, many of his former supporters (or simply people linked to him, like the former Nicaean Empress as well as his sister Costanza) fled the Kingdom of Sicily and took refuge in Aragon. The death of Corradino (executed in Naples in 1268 by order of Charles after the Battle of Benevento) and the fact that Manfredi’s sons from Helena Doukaina were just children and in French hands (they will die in captivity years later), made Costanza the only legitimate heir to the Sicilian crown. Starting this moment Costanza started being referred as queen (not infanta or madama) in the documents of the Aragonese Chancellery.

In 1276 James I died, and so Peter was crowned king of Aragon. In the meantime, Costanza had already given birth in 1265 (November 4th) to the firstborn and heir, Alfonso. Followed by another male, James (April 10th 1267), and then Isabella, future Queen consort of Portugal (1271), Frederick (December 13th 1272), Yolanda (1273) and finally Peter (1275). According to historian Muntaner, although it wasn’t a love marriage, Peter and Costanza came to care for each a lot and “there were never was so great love between husband and wife as there was between them, and always had been”.

On Easter 1282, Sicilians started their revolt against the French rule, starting the so called Sicilian Vespers. Peter was quick to reclaim the crown of Sicily and Apulia on behalf of his wife. To the eyes of many Sicilian nobles the King of Aragon could be considered their legitimated master due his marriage to Queen Costanza (”nostre natural senyor, per raho de la regina e de sos fills” ). Before leaving headed for Africa (from where he would launch his invasion of Sicily), Peter named Costanza and their son Alfonso regents of the Kingdom of Aragon during his absence. As soon as he took possession of the island, Peter asked his wife and their children James, Frederick and Yolanda to join him. When the Queen arrived in Trapani in the spring of 1283, she received a warm welcome and was saluted by the people as their natural leader (”cela qui era lur dona natural”; Bernat Desclot, Llibre del rei en Pere d'Aragó e dels seus antecessors passats, ch. 103).

It is around this period that her strained relationship with lady-in-waiting and de facto second lady of the Island, Macalda di Scaletta (wife of Alaimo da Lentini, Grand Justiciar of the Kingdom of Sicily), was born. Macalda, who is described by historical sources as an ambitious and greedy woman, had tried to seduce Peter of Aragon, but without success. Since the King had declared himself devoted to his wife, the Sicilian baroness developed a burning hate towards her rival, the Queen.

In Messina, Costanza could finally embrance her husband again, but their meeting only lasted three days and it was their last. The King named his wife Regent of the Kingdom of Sicily (“Quant lo rey hac estat ab sa muller e ab sos infants en la ciutat de Mecina, e hac stablit sos balles e sos vicaris per tota Cecilia, si los feu comandament que tots fessen lo manament de la reyna e de son fill En Jaume, axi com perell, e comana la reyna als homens de Cecilia e de Mecina, e sos fills”) and returned to Aragon as his rival, Charles of Anjou, had proposed a trial by combat (who would never take take place) to be ideally fought in Bordeaux to decide the fate of the contended Kingdom. Peter died two years later in Villafranca del Penedès (Catalonia), on November 11th 1285.

Before leaving Sicily, Peter had declared that the Kingdom wouldn’t be merged into the Aragonese-Catalan territories, mantaining his autonomy, and that in thet future the succession of the two reigns would be handled separately, specifically with the Sicilian throne bequeated to the second son (at that time, James, already named Lieutenant of the Realm).

With Peter dead, Costanza didn’t choose to rule over Sicily by herself despite being its titular queen, but, as it had already been decided, relinquished her rights to her second son James (although she would keep managing the island on his behalf), while Alfonso succeeded his father. In accord to the pre-nuptial arrangements, the Dowager Queen supported her teen son in the matter of ruling the Kingdoms he had inherited.

In 1284, Costanza’s milk brother, Roger of Lauria carried out a successful expedition in the Gulf of Naples. The admiral captured Charles of Salerno, the Angevin heir, and took him in Messina, where he was saved by the angry mob thanks to the intervention of the Dowager Queen. During the same raid, Lauria had freed Princess Beatrice of Hohenstaufen, Costanza’s younger half-sister. The Queen soon put her unfortunate sister under her protection, arranging Beatrice’s marriage with Costanza’s half-nephew, Manfredo IV Marquis of Saluzzo. The wedding was celebrated in October 1286 in Messina, and during the celebration the Princess had to give up on her rights to the Sicilian throne.

In 1290 she deployed troops to defend the city of Acre, but given the excommunication of Pope Martin IV against Peter III of Aragon and the Sicilian people, those troops were sent back. The following year, 1291, Acre would be conquered by Mamluk forces.

Also that year, Alfonso III died heirless. James succeeded him as King of Aragon, Valencia and Majorca, Count of Roussillon, Cerdanya and Barcelona, and, in normal circumstances, his brother Frederick would have inherited the Sicilian Crown, but James had other ideas. The new King kept Sicily for himself, naming Frederick Lieutenant of the Realm. The dispossessed Prince then left the Kingdom headed to Sicily, where he joined his mother Costanza.

Her son’s death represented a turning point in her life. Although already a pious woman, she started pondering about a future in the cloister and retired in a Clarisse nunnery she had personally founded in Messina.

In 1295, James signed the Treaty of Anagni, an accord signed by Boniface VIII, James II of Aragon, James II of Majorca, Charles II of Anjou and Philip IV of France, which should have put to an end to the Vespers War. As part of the terms, the King of Aragon had to return the island of Sicily to the Pope (let’s remember the fact that officially, since Norman times, the Kingdom of Sicily was actually one of the Papacy’s many fiefs, and that its lords were just lieutenants), who would in turn give it to Charles of Anjou, in exchange for the annulment of the excommunication weighing over him and the concession of the licentia invadendi (the permission to invade) concerning the islands of Sardinia and Corsica. The treaty required moreover a double dinastic union, James would have married Princess Blanche of Anjou, while her brother Robert was wed to James’ sister Yolanda.

There was someone in particular, though, who wasn’t happy about this settlements. Backed up by the Sicilian population who refused to return under French domination, Infante Frederick was crowned King of Sicily in Palermo on March 25th 1296, de facto nullifyng any attempt to stop the war.

This had a huge impact in his mother’s life. Unlike her son, Costanza had always recognized the Papal authority. By not accepting the treaty’s terms, Frederick had in fact rebelled against the Pope (not mentioning his own brother). Costanza chose then not to support him and, because of this, she had to leave Sicily since, as Papal emissaries put it, if she stayed she could be considered an accomplice (“E madona la regina Costança fo absolta per lo Papa, é tots aquells qui eren de sa companyia , si que tots dies oya missa; que axi ho hach a fer lo Papa, per convinença a les paus quel senyor rey Darago feu ab ell. Per que madona la regina parti de Sicilia ab deu galees , e anassen en Roma per pelegrinatge” in Crónica de Ramon Muntaner, ch CLXXXV).

Together with her longtime supporters, Giovanni da Procida and Roger of Lauria, in february 1297, she traveled to Rome where the Pope had promised to economically support her staying in Rome (although apparently it was a short-lived promise) and where she witnessed her daughter Yolanda’s marriage to Robert of Anjou. In 1299 the Dowager Queen returned to Catalonia and died in Barcelona on April 8th 1302 (“Non sine cordis amaritudine vobis presentibus intimamus quod die Veneris Sancta, quasi in media nocte, serenissima et karissima domina et mater nostra domina Constancia, fidelis recordacionis Aragonum regina, diem clausit extremum, ex quo tanto nos pungit doloris ictus acerbus quanto per eius obitum sentimus nos tante matris solacio destitutos.” in La muerte en la Casa Real de Aragón..., p.20).

Aside from many donations to various religious houses, in her will (dated february 1st 1299) Queen Costanza would include a small bequest in favor of her son Frederick with the condition he had to make peace with the Pope, observing thus the terms of the Treaty of Anagni.

She was buried wearing the Franciscan habit in the convent of St. Francis in Barcelona (“E a Barcelona ella fina , e lexas a la casa dels frares menors, ab son fill lo rey Nanfos, e muri menoreta vestida ” Crónica de Ramon Muntaner, ch CLXXXV). In 1852 her remains would be moved to Barcelona Cathedral by order of Queen Isabella II of Spain.

Sources

Claramunt Rodríguez Salvador, Alfonso III de Aragón

Corrao Pietro, PIETRO I di Sicilia, III d'Aragona in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 83

Desclot Bernat, Crónica

Ferrer Mallol María Teresa, Constanza de Sicilia

Hinojosa Montalvo José, Jaime II

La Mantia Giuseppe, FEDERICO II d'Aragona, re di Sicilia in Enciclopedia Italiana

La muerte en la Casa Real de Aragón Cartas de condolencia y anunciadoras de fallecimientos (siglos XIII al XVI), ARCHIVO DE LA CORONA DE ARAGÓN

Malaspina Saba, Rerum Sicularum

Muntaner Ramon, Crónica / translation by Lady Goodenough

Sicily/Naples: Counts & Kings

Walter Ingeborg, COSTANZA di Svevia, regina d'Aragona e di Sicilia in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 30

#historicwomendaily#history#women#history of women#historical women#costanza ii#House of Hohenstaufen#house of aragon and sicily#peter iii of aragon#norman swabian sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#vespri siciliani#myedit#historyedit

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

I didn't go inside -

Norman wingDetail

The palace stands in the highest point of the ancient centre of the city, just above the first Punic settlements, whose remains can still be found in the basement.[citation needed]

The first building was a Norman castle. After the Normans invaded Sicily in 1072 (just 6 years after they conquered England) and established Palermo as the capital of the new County of Sicily, the palace was chosen as the main residence of the kings. In 1132 King Roger II added the famous Cappella Palatina to the complex.[1][additional citation(s) needed]

During the reign of the Swabian emperors, the palace maintained its administrative functions, and was the centre of the Sicilian School of poetry, but was seldom used as permanent seat of power, especially during the reign of Frederick II.[citation needed]

The Angevin and Aragonese kings preferred other seats. The palace returned to an important administrative role in the second half of the sixteenth century, when the Spanish viceroys chose it as their official residence, carrying out important reconstructions, aimed at their representative needs and their military ones, with the creation of a system of bastions.[citation needed]

The Gallery of the Palace in 1686

The Spanish Bourbons built additional reception rooms (la Sala Rossa, la Sala Gialla e la Sala Verde) and reconstructed the Sala d'Ercole, named for its frescos depicted the mythological hero, Hercules.[citation needed]

From 1946, the palace was the seat of the Sicilian Regional Assembly. The west wing (with the Porta Nuova) was assigned to the Italian Army and is the seat of the Southern Military Region.[citation needed]

During the sixties, it received comprehensive restorations under the direction of Rosario La Duca.[citation needed]

The palace is also the seat of the Astronomical Observatory of Palermo.[citation needed]

The palace contains the Cappella Palatina,[2] by far the best example of the so-called Norman–Arab–Byzantine style that prevailed in the 12th-century Sicily. The wonderful mosaics, the wooden roof, elaborately fretted and painted, and the marble incrustation of the lower part of the walls and the floor are very fine.[3] Of the palace itself the greater part was rebuilt and added in Aragonese times, but there are some other parts of Roger's work left, specially the hall called Sala Normanna.[3]

0 notes

Text

The Cammino Basiliano: southern Italy’s newest walking trail

The Cammino Basiliano® runs north–south for nearly 1400 kilometres (1390 to be exact) across Calabria in southern Italy. This gorgeous region, occupying the “toe” of Italy’s boot, is famed for its dramatic landscapes. Sure enough, the trail laces its way through rugged mountains, traditional villages, plunging valleys and along a spellbinding coastline. It follows in the footsteps of the Basilian monks, a Greco-Italian order that followed the teachings of St Basil.

Starting in Rocca Imperiale in Cosenza and finishing up in Reggio Calabria (facing Sicily across the Messina Strait), the Cammino Basiliano® traces the Calabrian Apennines, part of the mighty Apennine mountain chain that forms the backbone of peninsula Italy. The route is divided into 73 smaller stages, and takes in the four massifs of Pollino, Sila, Serre and Aspromonte. Here, we explore Calabria’s Cammino Basiliano® is all its glory.

Why you should visit the Cammino Basiliano®

Following a series of mountain chains, the landscapes of the Cammino Basiliano® are the most obvious draw. Wooded ridges, rocky outcrops and sheer-sided valleys make for fine walking country, while the Calabrian coastline is picture-perfect. As you wind your way through charming historic villages that haven’t changed in decades, where fresh Italian cuisine is served farm-to-plate at the local trattoria, you’ll find a slice of authentic Italy every bit as alluring as the staggering views. Walking the Cammino Basiliano® in Calabria also encourages slow, sustainable tourism. Appreciating the area’s valuable ecosystems and putting money back into its communities – for instance by staying at local lodgings and dining on local produce – helps to secure the region’s future.

There is plenty to captivate culture vultures along the route, too. The region has been shaped by a number of different civilizations over the sands of time, occupied variously by Bruttians, Oenotians, Greeks, Romans, Saracens and Normans. Archeological remains, Byzantine relics and ancient places of worship have been left in their wake. You’ll discover brilliant Basilian monasteries, crumbling fortresses, Latin abbeys and shrines carved into steep mountainsides. And don’t forget to pause in traditional towns and historic hamlets to check out local handicrafts – they make stonking souvenirs.

From ancient mule tracks and gravel roads to seven sections designated as “wild” – read: for experienced hikers only – you can select a section to suit your ability and timeframe. Alternatively, walk the lot and cross a real once-in-a-lifetime experience off your bucket list.

Top highlights along the Cammino Basiliano®

1. Pollino massif

The first part of the Cammino Basiliano® in Calabria takes in the Pollino massif, characterized by towering mountain peaks and plunging canyons that will take your breath away. The rugged scenery heralds a series of peaks topping 2000 metres, laced by old paths and countryside tracks that can also be negotiated by bike or on horseback. The glorious mountainscapes – punctuated by historic towns with fine fortresses and rich cultural offerings – eventually open up to reveal spectacular views to the Gulf of Taranto and the Piana di Sibari. As the route leaves the mountains behind, the spires of the Pollino massif are replaced by gentle slopes carpeted in olive groves.

Highlights along the first section of the route include Rocca Imperiale, the startpoint, crowned by an imposing Swabian fortress, and the village of Oriolo, its Norman castle perched above the ancient village. Also not to be missed are Alessandria del Carretto, the highest village in Pollino National Park; the Shrine of Madonna delle Armi, built on an ancient Byzanitine monastic site; and Civita, notable for its Albanian community. Near the end of the section, be sure to spend time in San Demetrio Corone, once home to a Greco-Italian monastic community and site of the Abbey of Sant’Adriano, complete with exquisite Norman mosaic floor tiling.

2. Sila plateau

The second section of the Cammino Basiliano® stretches from Acri, the northern gateway to Sila National Park, to Tiriolo, on the isthmus of Catanzaro at the peninsula’s narrowest point. The landscapes along this stretch feature dense forests and dappled woodlands that are faintly reminiscent of Scandinavia, while there are more rich pickings in the form of religious and cultural sites. To top it all off, remote mountain villages herald old tuff caves created by monks seeking shelter and space for prayer.

The section kicks off in style with the sublime landscapes of Sila National Park; other scenic highlights along the way include Valli Cupe Natural Regional Reserve – towards the close of the Sila stretch, where you’ll find centuries-old chestnut trees, tumbling waterfalls and the Petra Aggiellu monolith – and the Lago Ampollino reservoir, flanked by pines. Expect superlative views of the Piana di Sibari from Corigliano Calabro, the Neto Valley from towering Santa Severina, and out over the Gulf of Squillace as you head towards Sellia Superiore. Cultural standouts, meanwhile, include the 11th-century Abbey of Santa Maria del Patire; the Byzantine centre of Rossano; the Romanesque abbey of San Giovanni in Fiore; and Catanzaro, the region’s administrative capital and home to a collection of noteworthy historic buildings.

3. Serre Calabresi

The third part of the Cammino Basiliano® in Calabria runs along the Serre Calabresi, with forested mountain slopes, ancient monasteries, enigmatic hermit caves and sweeping coastal vistas. Spiritual sites are king here, and you’ll find endless monasteries, churches, hermitages and shrines to admire along this section, which ends in Gioiosa Ionica.

Highlights in the Serre Calabresi include Squillace, where the Monastery of Vivarium was founded in the 6th-century, renowned for its ceramics. Search for souvenirs before enjoying the tremendous views over the town’s namesake gulf. Badolato’s Church of the Immacolata, set adrift from the village on a narrow strip of land, is another showstopper, while the Byzantine Valley of Stilaro, surrounded by a trio of villages, sports an 11th-century monastery in Bivongi, hermit caves dating to the 6–7th centuries in the side of Mount Consolino, the Cattolica of Stilo, and a standout shrine to the Madonna della Stella in Pazzano, complete with a 10th-century fresco.

4. Aspromonte massif

The last stage of Calabria’s Cammino Basiliano® has jagged peaks, towering rock spires and a fascinating sense of living history. It’s here, in the Aspromonte massif, that you’ll find the last Calabrian-Greek (or “Grecanico”) speaking communities. The Grecanici are descended from the once sizable ancient and medieval Greek communities of southern Italy; today, alongside the archeological sites and religious relics you’ll have come to expect from the region, these unique communities are a joy to explore.

The Aspromonte section starts in Gerace, with the remains of a Norman castle, an imposing 11th-century cathedral and the pretty Piazza delle Tre Chiese. Bianco – the land of Greco wine – and Samo – home to the area’s finest Byzantine-Noman monument in the form of the Church of Santa Maria dei Tridetti – are both worthwhile stops, too. But the real draw of this region lies in its Grecanici communities, enduring bastions of Greek history, culture and tradition. Visit Bova, the capital of Greek Calabria, topping a spur 820 metres above sea level; Gallicianò, with its orthodox Church of Panaghìa tis Elladas, dedicated to Madonna di Grecia; or Pentedattilo, which was likely used as a fortress in Greco-Roman times.

The Cammino Basiliano® finally comes to its conclusion in Reggio Calabria, with a fabulous seafront location and unforgettable views to Sicily across the Messina Strait. Drink them in.

To read the whole article, click here.

Follow us on Instagram, @calabria_mediterranea

#calabria#italia#italy#italian#south italy#southern italy#mediterranean#europe#mountains#mountainscape#mountain#mediterranean sea#beautiful views#italy destinations#villages#byzantine#history#italian landscapes#italian landscape#landscapes#landscape#pollino#sila#aspromonte#art#woods#woodland#greenery#nature

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The castle at Castellammare del Golfo (which means Castle of the Gulf on the Sea) was first built by the Arabs then rebuild by the Normans and then the Swabians. It once had a drawbridge. Today, from town you can walk across a modern bridge to access it. From this perspective on the sea it is hard to see how large the fortress is, but it's very impressive up close! Inside are two ethnographic museums curated by the town. One dedicated to tools used by farmers who worked the land and by craftsmen who worked in town, the other dedicated to fishing, specifically tuna fishing that was a main industry here for centuries. #thisissicily #experiencesicily #seeyousoonsicily #sicily #castellammaredelgolfo #castle #castello #sea #mare #sicilia #siciliabedda #italy #italia #sicilyvacation #sicilians_world #ig_sicily #igerssicilia #instasicilia #gf_italy #siculamenteDoc #sicily_tricolors #ig_visitsicily #Sicilia_PhotoGroup #smallgrouptours #traveltogether #authenticsicily #sicilytour #whatsicilyis #sicilytravel #viverelasicilia (at Castellammare del Golfo) https://www.instagram.com/p/CFrmLsalc2R/?igshid=12iwjp25hz7ms

#thisissicily#experiencesicily#seeyousoonsicily#sicily#castellammaredelgolfo#castle#castello#sea#mare#sicilia#siciliabedda#italy#italia#sicilyvacation#sicilians_world#ig_sicily#igerssicilia#instasicilia#gf_italy#siculamentedoc#sicily_tricolors#ig_visitsicily#sicilia_photogroup#smallgrouptours#traveltogether#authenticsicily#sicilytour#whatsicilyis#sicilytravel#viverelasicilia

1 note

·

View note

Note

what do you think are some underrated Italian cities to set aesthetic books or movies in? Both historical and modern

That's such an interesting question, I love it! I think most #aesthetic books/movies are usually set in like Rome or Naples (a very generic '60s Sicily plagued by mafia too, at times) and for more historical media I'm guessing Venice and Tuscany in general + miscellaneous cities in Emilia-Romagna, so pretty much anything but these, but I'm going to pick a couple of cities specifically!

First off, Renaissance Messina, my very hometown: Messina was one of the richest and most beautiful cities in Italy, especially due to its location which made it an excellent harbour and trade city for merchants (as happened with its twin sister Reggio on a slightly smaller scale). It found its luck especially in the Renaissance, with Antonello da Messina paving the way for a whole group of Sicilian artists which came to live in Messina along with many more Italian artists and merchants, mostly from Venice, Naples and Florence, AKA the best-known "Renaissance capitals" of the time. It's even speculated that William Shakespeare himself was Messinese and later moved to Verona and then England, and though that is kind of a far-fetched theory, it shows just how much importance the city held back then! Messina, however, has been plagued by earthquakes since forever, due to its unstable position on two different tectonic plates, and as such it'd be quite hard to film a Renaissance (or anything pre-1908) movie in it, unlike, say, Florence or Venice. I'd still absolutely love to read a book set in Renaissance Messina, or even in a fantasy city inspired by it!

Anywhere in Sardinia: aside from it having a very peculiar and unique history and culture which would make for a lovely period movie, Sardinia has also been blessed with some of the most beautiful sights and scenarios in the world: crystal-clear seas, cacti on rocky cliffs alongside sandy golden beaches, I bet the island's pro loco team doesn't have to make a lot of effort to make it seem like heaven on earth! The economy is mostly rural, with a majority of the inhabitants, especially in the most central places, living off animal and in particular sheep and goat husbandry, so it'd be the perfect location for one of those "rural paradise" films (this doesn't mean life is perfect in Sardinia, by all means, we've recently had a wave of protests against the extremely low prices of milk which spread to Sicily as well, but the setting's still awesome and Oscar-worthy).

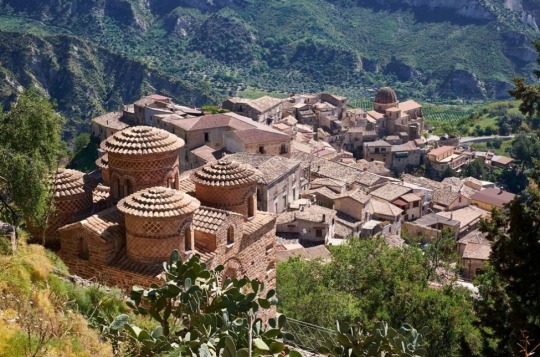

Norman-Swabian Palermo: I know I've said it time and time again, but the fact that we haven't yet had a period drama about Costanza of Hauteville or Federico II is a terrible shame, especially since most of the architecture of the time is still extremely well-preserved and Palermo looks that beautiful! It would be a Medici-worthy production, in my opinion, especially when I think about my love Federico II and his illuminated monarchy centuries before that was a thing❤ Of course, that would also be a great opportunity to showcase most other Southern regions, especially Apulia and Calabria which are criminally underrated in movies, so that'd kill many a bird with one stone!

Those are the main cities I can think of off the top of my head, but I will reblog this if any other cities -- of which I'm sure there are plenty -- come to mind, and in the meantime my followers are more than welcome to add onto this post!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LO STILE CHIARAMONTANO - Palazzo Steri a Palermo, Cortile Santo Spirito Agrigento, Castello di Caccamo, Corte interna Castello di Mussomeli, Castello di Alcamo.

Dopo i grandi e potenti re Normanni e svevi, furono i baroni ed i principi siciliani ad occuparsi della costruzione di grandi opere religiose e militari. Tra questi, arrivati con i normanni, vi furono i Chiaramonte, di origine francese, che tramite matrimoni ed acquisizioni diventarono nel 1300 una delle famiglie più potenti della Sicilia. Signori della ricchissima contea di Modica, i Chiaramonte avevano possedimenti sparsi in tutta l’isola essendo signori di Ragusa, Scicli, Pozzallo, Ispica e Chiaramonte Gulfi, Naro, Bivona e Lentini. Potenti tanto quanto i re di Sicilia, rinforzarono il loro potere tramite la costruzione di castelli come quelli di Favara, il castello di Monforte, Palma di Montechiaro, Racalmuto, Gela, il castello di Mussomeli, il castello di Falconara presso Butera, di Alcamo e Caccamo. Castelli solitari, poderosi e massicci a sfidare apertamente principi nemici e re invidiosi della loro ricchezza. In qualità di signori di Agrigento l’abbellirono con chiese, monasteri ed altre opere, mentre fecero della loro residenza a Palermo, il Palazzo Steri, una reggia esternamente massiccia come tutti i loro castelli ma internamente elegante e superba. Le loro costruzioni avevano degli elementi costanti, il famoso gotico Chiaramontano, dove venivano ripresi alcuni elementi tipici normanni come ad esempio la realizzazione di finestre ad arco acuto circondate da decorazioni chiamate “baton brises”(bastoncini rotti) una decorazione architettonica distintiva dell'architettura gotica del nord europa e in particolare dell’Inghilterra. Estinta la loro famiglia le loro proprietà passarono ai loro nemici, i conti Catalani Moncada e Cabrera che comunque si preoccuparono di mantenere la bellezza (e il potere) delle magnifiche opere dei potenti Chiaramonte.

Chiaramonte architecture style

After the great and powerful Norman and Swabian kings, it was the Sicilian barons and princes who took care of the construction of great religious and military works. Among these, arrived with the Normans, there were the Chiaramonte, of French origin, which through marriages and acquisitions became one of the most powerful families in Sicily in 1300. Lords of the rich county of Modica, the Chiaramonte had possessions scattered throughout the island being lords of Ragusa, Scicli, Pozzallo, Ispica and Chiaramonte Gulfi, Naro, Bivona and Lentini. Powerful as the kings of Sicily, they reinforced their power by building castles like those of Favara, the castle of Monforte, Palma di Montechiaro, Racalmuto, Gela, the castle of Mussomeli, the castle of Falconara near Butera, Alcamo and Caccamo. Solitary, powerful and massive castles openly challenge enemies and envious kings of their wealth. As lords of Agrigento they embellished it with churches, monasteries and other works, while they made their residence in Palermo, Palazzo Steri, an externally massive palace like all their castles but internally elegant and superb. Their buildings had constant elements, the famous Chiaramontano gothic, where some typical Norman elements were taken, such as the realization of acute arched windows surrounded by decorations called “baton brises” (broken sticks) a distinctive architectural decoration of Gothic architecture of northern Europe and particularly of England. Their family was extinguished and their property passed to their enemies, the Catalan Moncada and Cabrera accounts, who however were concerned with maintaining the beauty (and power) of the magnificent works of the powerful Chiaramonte.

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CASTELLANA GROTTE is an Italian town in the metropolitan city of Bari, in Puglia. Located on the limestone plateau of the Terra dei Trulli and Grotte, it is known above all for the karst complex of the Castellana Caves. It was born in the early Middle Ages thanks to the colonization carried out by the Monastery of San Benedetto di Conversano in the 10th century, precisely in 901. This is testified by a parchment that refers to the deed of sale of Ermenefrido, son of Ermuzio, and his wife Trasisperga to favor of Ianniperto. The document speaks of a Castellano Vetere and a Castellano Novo. In 1098, Count Goffredo di Conversano, of Norman origins, donated the whole territory to San Benedetto and allowed the abbot to gather people there to populate it. Its official foundation is traced back to December 1171, when the Abbot Eustasio donated the feud of Castellano with good vassalage conditions to two Otranto, Nicola and Costa, in an attempt to repopulate the agglomeration of existing houses, many of which were destroyed. during the disputes between Roger II of Sicily and the Norman dynasts, to enjoy their income again. The reconstructed vicus village soon became a universitas and, in this period, the presumed visit of Frederick II of Swabia and his one night stop under the now non-existent Elm of Porta Grande is placed. During the Swabian domination the Conversano monastery of San Benedetto was abandoned, and in 1226 Pope Clement IV granted the Convent of Conversano to a group of Cistercian nuns who fled from the Morea, a region of central Greece. They are assigned all the properties of the ancient abbey, including Castellana, and the ecclesiastical jurisdiction: that is, the ordinary power over the clergy and people of Castellana plus the right to challenge the pastoral and gird the miter. In 1938 the town underwent a tourist turn, thanks to the discovery of the caves by professor Franco Anelli assisted by Vito Matarrese (who later discovered the White Grotto himself). In 1950 the name of the municipality was changed from Castellana to Castellana Grotte, in homage to the discovery. (presso Grotte di Castellana) https://www.instagram.com/p/CEPVAiHIcw0/?igshid=1xi809vv2lh1d

0 notes

Photo

A fortress fit for a Duchess. A short walk, down the winding lane from the Bari Cathedral and I sight the lush green parklands, surrounding the fortress of the Norman-Swabian Castle (Castello Normanno Svevo). 💕 Normally there is an entrance fee, however on the day of my visit it was free. 🙂 The inner walls with towers built by the Normans in the early 12th century were originally built for defensive purposes. However, these mighty defence walls were unable to hold back the invasion by William I of Sicily in 1156 and saw the castle destroyed. 💕 The present day castle was built on the original site by Frederick II of Hohenstaufen an illustrious man, having held the titles of King of Sicily, King of Germany, King of Italy, King of Jerusalem and Holy Roman Emperor during the late 12th and early 13th centuries. The castles restoration was carried out during 1233, highlighting its residential and symbolical aspects. 💕 During the 16th century the castle fortress was surrounded with rampart on three sides and turned into a harmonious and stately complex suitable to accommodate the court of Isabel of Aragon (Duchess consort of Milan, by marriage and Duchess of Bari) and her daughter Bona Sforza (who became Queen consort of Poland, Grand Duchess consort of Lithuania and following her Mother’s death in 1524 Duchess of Bari). 💕 Today, one can walk through the courtyard and along the passages whilst admiring the beautiful architecture. There’s also an opportunity to watch a visual presentation in one of the ground floor rooms of the castles history through the years, and is presented in various languages. 💕 Where and what time of the year have you visited an historic site and found it was free on the day of your visit? Swipe 👈 to see more. You can read 📖 more about Bari's historic beauty and treasures over on the Blog. https://asoulawakening.com.au/bari-historic-beauty-and-treasures/ See link in bio. Subscribe and receive the latest blog posts directly to your inbox. Like and leave a comment below, share your thoughts 💭 🙂 https://www.instagram.com/p/B566ibyl54n/?igshid=ke3lxdahz5x9

0 notes

Text

Abruzzo: Turn off the phone

(Photos by Kateri Likoudis Connolly)

Cathy and I stood at the edge of the piazza, a stone-paved square overlooking the San Leonardo pass between the Majella and Morrone mountains. The sun was setting behind us and the Morrone, giving the valley beneath an amber glow. Above the tree line across from us, the rocky face of the Majella turned magenta. We were in Roccacaramanico, a quasi-abandoned medieval town in Abruzzo's Majella national park. Riding a spur on the Morrone's eastern slope, the town is a cluster of stone houses built along and above one main street. Beyond the cars parked at the entrance to the village, where there are also some collection points for recyclables, there's little in the town that breaks the spell of being in the 13th century. Few people live here year-round. Shepherding and farming are not the prevalent activities they once were. Most villagers have moved elsewhere, many to America. Restored homes offer shelter to hikers and other park tourists. From spring to fall, there're almost always visitors.

The late June day had been hot, but the air was clear and cooled as the sun retreated. It was just before dinner, and the tavern that opened onto the square was preparing for business. A large, white Abruzzese sheepdog dozed next to us. A few older women sat at a table, laughing and exchanging stories in the local dialect. The woman who ran the tavern set their table. Happy voices and the clink of silverware. Rosemary and mountain grasses perfumed the air.

Not much else was happening. Or was likely to happen. The dying sun painted the mountains and the valley below. Breeze played in the beech trees. In the piazza, an ancient hospitality unfolded without fanfare or fuss at a single table. And it was perfection. Cathy and I shared a moment of comfortable silence, a privilege of a quarter-century of cohabitation. No need for words. Just our senses taking it all in. It helped that our sole link to the outside world (and often a conduit to hell), Cathy's smartphone, had died a day earlier. There was no way for anyone to disturb us. No way for us to try to capture the moment, Instagram it, frame it for the appreciation and approval of others. There was only the moment.

And that’s the point of Abruzzo. If you just shut up, kill the internal narrative that constantly rates and tries to validate your experiences, allow yourself to be present in the moment, it might be just what you need. You can’t capture, package, or sell its gift. There's just its intrinsic value. Which is why it’s so difficult to explain the region's allure. Why marketing it is difficult and can lead to something like sin.

In the last few years, Abruzzo’s been pegged in outlets as the “next place in Italy to discover.” It seems to be taking a long time. But I’m all for the right people discovering my favorite part of the world. Abruzzo and our friends there need the right type of tourism, and, so, the right type of tourist. Which means how word gets out, what gets told, and who does the telling are critical. About these parts of the discovery process, I’m not all that sanguine. We’re not good at subtleties, nuance, or depth. We don’t even seem to want to be. So far, most reportage has been spotty, often perfunctory, and woefully incomplete. I fear it will create unrealistic and unreasonable expectations. Americans and other first worlders expecting some quaintly rustic but gussied-up Tuscan-style idyll will be disappointed and angry. That would be tragic. Abruzzo welcomes visitors warmly and sincerely, in generous ways that can humble, but makes very few concessions to them. It remains, mostly, for now, its raw, sometimes ramshackle, but (in my mind) best self. It’s kind of important to report its complex truths, as much as that’s possible, and to approach it without preconceptions.

We've been traveling in Abruzzo for over twenty years. We lived for a short time in the village of Assergi, part of the Comune of L'Aquila, Abruzzo's capital, beneath the Gran Sasso massif. We started out to find my paternal family, then to write a travel book on the region. The latter never happened. Instead, we opened Le Virtù, our Abruzzo-themed restaurant in South Philly, a neighborhood that was a landing point for part of the region's diaspora. Largely undisturbed in its core by major highways until the 1970's, one of Italy's most mountainous and rugged territories with over thirty percent of its whole dedicated parkland (there are four major parks- three national and one regional - and several wildlife reserves), Abruzzo’s kind of a sanctuary for traditions and ways of life that have elsewhere vanished. Ancient pagan rituals and celebrations, now under the guise of Catholicism, persist. Shepherds still roam the mountains with flocks of goats and sheep. Agriculture continues to be defined by small family farms and cooperatives. Local cuisine resists homogenization and profits from an ingredient pool that would be the boast of better known, more traveled destinations in Italy. The region, once the northernmost part of various southern kingdoms (ruled by, among others, Normans, Swabians, French from Anjou, Spanish from Aragon), represents a bridge between south and central Italy. Though culturally and historically tied to the kingdoms of Naples and the Two Sicilies, its geographic position means that, especially at the table, it shares a lot with its central neighbors. Saffron, truffle (black and white varieties), porcini, game, tomatoes, red garlic, mozzarella, pecorino, and peperoncino – ingredients spanning central and southern Italy - are all major players in the Abruzzese kitchen.

Before we opened Le Virtù, Cathy and I organized small culinary tours - fifteen people maximum - of the region. We went to every type of eatery, from roadside, mountain arrosticini (lamb skewers) stands, mom-and-pop menu-less trattorie, and centuries-old, repurposed wooden fishing platforms to gastronomic temples of decadent excess. I've consulted with journalists working on pieces about Abruzzo for The New York Times, Food & Wine, Elle, and Saveur. We did a blow-by-blow account of one of our restaurant research trips for Food Republic. We could write up a Best-of tour of Abruzzo. Nature. Culture. Food. And you would have a spectacular trip. My problem is that you might not have really experienced Abruzzo.

A few years ago, a food writer friend of ours who also knows Abruzzo floated the idea of us putting together and following a comprehensive itinerary in the region for a major magazine. It would allow for the necessary time (Abruzzo's topography and challenging road networks make traveling in it time consuming and complicated) and include the "essential" places. From the mountains to the sea, we'd do the region right - or as close to right as was possible in a magazine feature. From the outset, we were aware of the limitations of the medium and any itinerary. But we knew and loved the region. We were the right people for the job.

At the outset, the magazine was gaga over the idea. Abruzzo was just then entering the “next place” conversation. We submitted our proposal. The magazine expressed its enthusiasm. And then everything went radio silent.

Several months later I received an email from a journalist who was working on an assignment about Abruzzo. He needed help lining up the right people to interview about the region's culture and history and wanted some additional info on a couple of its core traditions. I asked which magazine had hired him. It was, of course, the one we'd given our itinerary. He was cagey about giving up details of his own trip, but eventually had to reveal enough to allow me to arrange things for him. His tour would be abbreviated, but it included spots from our itinerary. Was I angry? Yeah. But he seemed a nice enough guy, maybe with no idea about what'd transpired, so I - with the blessing of our friend - opted to help. He'd no knowledge of the region, the distances he'd be traveling, or the nature of the topography and roads. He needed a translator. The trip our friend and I'd planned had been honed to seven days (and we were still uncomfortably conscious of all the things we'd be leaving out). He’d allowed for less than half that time.

The article came out, and to some fanfare. And it missed the point. Entirely. Truth is, most likely, ours would've too. Though we'd have gotten closer to the genuine article. It's somehow important to know enough to know what you're leaving out, what can't be adequately expressed or described. Even just to know what you don't know. One of the things that formed the core of this guy's piece, and that I'd set up for him, an interview with an aristocratic academic, an expert on the region's history, culture, and cuisine, was especially illustrative of the issues confronting any travel writer visiting Abruzzo for the first time. The professor made for great copy. Eccentric visually and personality-wise, he could wax for ages with unquestioned authority about the region. He was spectacular. But in a lot of ways, one would get a better read on Abruzzo's character and (sometimes grim) realities by talking to some laconic guy on a tractor, a woman wielding a sickle in a field, an old man carrying a bundle of kindling for his fireplace, or a sun-beaten dude tending his flock. Maybe even just a woman taking the orders AND cooking the food at her little trattoria.

The problem is, it's difficult to make the real stuff not sound a little sad. Because, in a way, it is. Anything truly complex and beautiful will contain melancholy elements. Adults should know this. Every beautiful thing - past, present, and future - is imbued with a kind of nostalgia or knowledge of its (or our) ephemerality. What you experience in Abruzzo, regardless of its very real vitality and beauty, is something that is endangered by the 21st century, something that is - in part - in decline or dying. The stuff that persists is kind of magical and occult in a century that seems bereft of meaning or values. But it’s in peril. Over its history, Abruzzo has endured earthquakes, war, endemic poverty, mass emigration. They’ve all left a mark. To be in one of Abruzzo's villages or in any of its parks offers exposure to things - rhythms, ways of life, connections to nature, a sense of community - that are essential, sustaining, deeply human. The sadness of history, the cruelty of commerce and nature, are also everywhere evident. It does the soul good to experience this totality. A visitor realizes that her very presence could be part of the problem. But also - if she’s open to experience and treats the region with respect and doesn’t impose ridiculous and shallow expectations - possibly part of the solution.

It's nearly impossible to capture this in a genre at least in part focused on first-impression narratives and/or glossy hyperbole. Abruzzo can’t be truly presented in an Instagram feed or its journalistic equivalent. But maybe that type of wide-eyed "discovery" is just what most magazines want. Maybe these well-meaning, ignorant, gob-smacked purveyors of “WOW” are the right people for the job and this age. They won't bore you with the complexity, the multifaceted, unvarnished, and not all-bright-and-smiley truth. They will fill you with the need to have (purchase?) "experiences," to validate your existence.

I don’t think that serves Abruzzo. Or the reader, for that matter. It won’t prepare her for the real experience or give her an idea of what essential things she might find there, and how to discover them. It’ll just create unrealistic and kind of rote expectations. Reportage and promotion of Italy suffer in general from shallow, romantic portrayals. Abruzzo’s impressive, moving, and - I think for what ails us - important. But it’s not particularly romantic. And I’m guilty of advancing some of this horseshit.

Somewhere along our 20-year timeline - for a short time, but still - I started "seeing" Abruzzo in terms of "wow factor." When we decided to marry our fortunes to Abruzzo - first with a never-produced book, then with small culinary tours, and finally with Le Virtù - it was inevitable that, to some extent, I'd commodify the region and its beauty. In the selling of something, regardless of how earnest the seller and heartfelt the sell, there's some reduction, some packaging that simplifies the truth. A gloss gets applied. I've played up Abruzzo's natural and man-made beauty and waxed poetic about meals and the people we've met - to attract journalists, to sell tours, to draw customers to our restaurant. I created an attractive, pleasant veneer. This was partly a product of the industries we’ve worked in and how they’re marketed and portrayed. TV shows, social media discussion, and journalism about travel, food, and restaurants have long been plagued by an obsession with "wow," presentation, and romantic imagery - the winemaker pensively walking among his vines, the chef intensely inspecting produce at the local market, the choreographed dance in the suggestively lit dining room. As opposed to a window on culture, a soulful gift, and congress with an actual community (things Abruzzo and southern Italy offer in spades), restaurant culture, in particular, and our expectations of it have too often veered toward the performative, the attempt to "blow the mind," present a seamless, theatrical experience. I find it all kind of empty, regardless of how impressive the show.

Eating in Abruzzo very often affords you the chance to have real contact with the culture, to meet and talk to the people making and serving your food, and to really get to know who they are, what makes them tick. It’s a window on what life’s like, what these people value, deal with, do. Asking questions - or being asked questions- that break down the wall between diner and restaurateur is how we came to truly know the region. Some of the frankest, most revealing discussions I’ve had about life in Abruzzo - not just restaurant-related stuff, but the day-to-day struggles, cultural values, and current events - have happened at tables in the region’s trattorie and ristoranti. Being open to this kind of exchange is essential to knowing the place. If that’s what you’re about. These days, you can eat well almost anywhere. Travel’s about something deeper.

But some travelers, including some journalists, refuse to go there. And, so, their experiences and impressions lack depth.

We were sitting at a little place in San Vito Chietino, along Abruzzo’s southern coast, as guests of our olive oil rep. The trattoria, built into a centuries-old, vaulted, brick, ground-floor space, was just steps off a pebble beach. From our table, we could hear the waves break and retract through the clicking stones. The food was simple but perfectly prepared. An array of lightly battered fried fish to begin, followed by a soup of tacconcini - small squares of pasta - in a tomato and red pepper broth flavored with the local granchi, tiny crabs cooked whole. Too small really to break open for their meat, they infused the broth with a sweet, rich flavor.

After the pasta course and before the arrival of our secondi, the restaurant owner, a short, solidly built woman in her mid-50's, approached the table to check on our progress. The rep, a sharp-witted guy who'd traveled the world from this area to sell his olive oil, asked her about business. And she told him. No filter. She let loose a restaurateur's laundry list of laments. It was an uncensored exchange between members of a closely linked community. Hand gestures, facial expressions, modulations in volume, angry in parts, wickedly funny in others. Fishermen, winemakers, farmers, all her purveyors (remember she was saying this to someone who is also HER olive oil rep), and customers were unreliable, unreasonable, obtuse, and getting on her last nerve. When she walked away, he looked at us sheepishly. He hoped our host hadn't been too familiar, honest, free with her words. But after traveling in Abruzzo for decades this was nothing new for us. He was relieved. A few weeks before, he told us, he'd been escorting a New York Times journalist around the region. The writer was put off by the regional lack of filter, the informality and familiarity of many restaurateurs and servers. Sophisticated, professional detachment was apparently an essential part of how he judged a dining experience. It was what he expected.

I can’t express how far up his own ass this Times guy was, and how tragically wrong for this assignment. Why travel at all if your mellow gets harshed when the local character doesn’t conform with your staid and, frankly, ignorant expectations? Is this the kind of intrepid correspondent that will bring us any true picture of the world beyond our experiences? This was a guy who maybe should never roam beyond small sections of Manhattan. He sure as hell wouldn’t cut it in most of South Philly. It’s important who gets to tell us these stories.

Over ten years ago, we took a friend of ours, Toronto-based, early modernist historian and author Mark Jurdjevic, to a tiny trattoria in the village of Ofena, just under the Campo Imperatore high-mountain plain in the Gran Sasso National Park. The woman who ran the place was a friend of ours. The trattoria was in what had been her childhood home. Her cucina was simple but elegant, using the best of the local ingredients - the potent saffron from the nearby Navelli plain, black truffles and wild herbs from the surrounding mountains, Santo Stefano di Sessanio lentils (small, dark, and for my money more flavorful than their counterparts from Castelluccio in Umbria), porcini, red and black ceci, and cicerchie (kind of misshapen, meaty, ceci-sized beans). Six or seven years earlier, Cathy and I’d stumbled on the place while exploring the village. The dining room walls had been painted by our friend’s artist husband in a riot of swirling greens, golds, and earthy reds. It was like dining inside a Van Gogh or Monet. Our first meal there included an antipasto della casa that might not have ever ended if we’d not cried “uncle.” Local pecorino cheeses, salumi, bitter greens sautéed in garlic and hot pepper, frittata, coratella (bits of lamb and lamb offal fried and browned in oil with garlic, white wine, salt, pepper, and some herbs), and grilled vegetables all arrived in turn. The most unusual item was a plate of lightly battered and fried lamb’s brains. They were creamy, almost like custard, with a mildly sweet, subtle, and elusive flavor. Not like anything I’ve had before or since.

This visit with Mark, who’d used his genius for writing proposals to earn two years of study in Firenze, was my attempt to give him an authentic taste of Abruzzo, a change of pace from what he’d been daily experiencing in Tuscany. In so many ways, the meal delivered. Its events are apparently seared into his memory.

I emailed Mark to tell him I’d be writing about this. And he responded in seconds:

“Precise memory: fresh pasta alla chitarra (bright yellow - brighter than I've ever seen - the eggs, right?), saffron, slightly roasted cherry tomatoes, with a basket of chilies on the side. I think we grated some pecorino on it. It was one of, if not the, most satisfying pastas I've ever had. I came home (to Firenze, where he was then living with his wife and daughter) with a bag of saffron and tried to re-create it about ten times. It seemed so simple that it should be easy. Every pasta I made was certainly enjoyable, but not the same.

“Vague memory: Cathy had talked about an endless appetizer parade. The parade was considerably smaller than she had experienced the previous time, which we attributed to the fact that she (our friend) was with us in the dining room weeping and venting, rather than in the kitchen where such parades start. I remember some fried polenta with braised mushrooms and a stewed pepper dish, slightly spicy. Pretty sure secondi were grilled, split salsicce.

“Most I remember the outpouring of pure, unmitigated grief, combined with my shame and guilt that every ten minutes or so I would wonder if she was going to get her shit together and cook me some more food.”

During the previous winter, then just ended, our friend’s father had fallen gravely ill - I don’t remember the malady, but the situation was hopeless. Winters in Abruzzo’s hinterlands can be extreme, Jack London-level stuff. Meters of snow. Howling winds. Wolves. The trifecta (though the third element never actually hurts anyone). The condition caused the father terrible pain. But the town’s remoteness and the snowfalls that sometimes blocked the roads made caring for him impossible. The travelling doctor couldn’t get there. So, there were no pain killers to lessen his suffering. His wails filled the house for days before he died. In Mark’s words, “…she was grabbing your forearm with both hands as she wept-spoke the details.”

In the summer of 2011, several years later, Cathy and I dropped by the village of Santo Stefano di Sessanio, in the Gran Sasso National Park. It was two years after the April 2009 earthquake that’d nearly destroyed L’Aquila, Abruzzo’s capital city, and damaged and traumatized the surrounding towns that were part of the “crater” around the epicenter. Santo Stefano was one of these. Last time we’d visited, three months after the quake, most of the town - a fairytale-like, medieval jewel located, like Ofena, just beneath the Campo Imperatore - had been inaccessible. We were anxious about what we’d find.

An enormous crane hovered above the space where the town’s signature central tower, a crenulated lookout built by the Medici, had stood. It had toppled during an aftershock. Metal and wooden bracing secured many of the buildings in town, but some of the shops and eateries were open. We passed one of our favorites, Tra Le Braccia di Morfeo, and were happy to find it ready for business. Looking in from the street, I could see the owner/operator, Francesca, seated at her bar reading a newspaper. We’d not seen her since the quake.

We’d known Francesca for over five years. During our many visits (including stops on our tours), she’d always been welcoming, but kind of reserved, professional. Not this time. We entered, and her face beamed with delight. She embraced each of us in turn. “Volete mangiare? Spero di si!” (You want to eat? I hope yes). A familiar and welcome meal of rustic specialties followed. First salame aquilano - firm, tightly packed and flattened, and spiced with salt and pepper. Then liver sausage, house-cured, thick-cut, mountain-style prosciutto, capocollo, pickled zucchini, and local aged canestrato pecorino. For my primo, I went with the zuppa di lenticchie, made with the town’s prized lentils. Cathy devoured a robust casareccia pasta served with tomato, shaved pecorino, and fresh peperoncini (chilies), which she cut over the dish at the table with scissors. We washed it down with a bottle of local cerasuolo, Abruzzo’s deeply-hued, full-bodied rose’ made with the Montepulciano grape.

It was all almost normal. Sated, content, and ready to nap, I still wanted to talk to Francesca, hear how it was going. So, I asked. And Francesca, who understood that I wasn’t expecting bullshit, opened a can of verbal whoop-ass. "Male, molto male," she began, then launched into a blistering oratory that, though economical, took no prisoners, and built in intensity:

“Besides the first few days, they've done nothing. And they won't allow us to do anything ourselves. Have you seen L'Aquila? It's almost as it was right after the earthquake. Two years. Two goddamn years, and they've done nothing and are doing nothing. Where did all the money go? They brought the G8 here, the idiots-” Berlusconi, who unsurprisingly botched the recovery, had moved the 2009 conference from Sardegna to L’Aquila to highlight the damage for world leaders – “for a show. A show for whom? Lots of talk and promises. And now? How do we survive in the park with L'Aquila left in ruins? They don't give a damn about us, we who live by the park, work with nature. How are we supposed to survive?”

Francesca - blond, sharp-featured, slight of stature, but as solid as a foot soldier - seemed about to splinter into a thousand pieces, her body unable to contain her rage. She seemed indifferent to the effect of her rant on the other two couples, both Italian, in the dining room. Cathy and I sat in silence and listened. It's all we could do. She finished and apologized, but this is what I’d asked to hear: the truth. Her goodbye was as warm as the welcome. She grabbed my hands, kissed me on each cheek, and we walked out nourished but without illusions.

While I might be able to paint a soft-focus, alluring picture of experiences in Abruzzo, I’m permitted no easy fantasies about an idyllic life nestled in the very real, spectacular beauty of Abruzzo’s mountains. Under certain circumstances, the scenery can kill you.

For each one of these moments (and others) of unvarnished and uncomfortable truth, I can name hundreds of unmitigated joy: family dinners gathered around a table covered in steaming polenta and ragu’; eating grilled lamb and drinking wine on the Gran Sasso mountain under a canopy of stars; restaurant meals ending with uncounted rounds of house-made digestivi brought to the table by the chef/cook, who then sits down with us; sharing a table under a pergola overlooking grapevines and olive groves with winemakers who drove up to the meal on their tractors; gargantuan feasts lasting hours with course after course in gastronomic temples helmed by master chefs. All these episodes unspool in my mind in a gilded light, like childhood memories. But all of them are also informed, made more special and precious, by an understanding of how delicate and precarious the whole thing is, how bad things can go, and how hard life in these mountains can be.

Because Abruzzo and its people aren’t just battling the natural elements, the ageless challenges of mountain living, farming, and shepherding. They’re fighting the 21st century, it’s suicidal indifference toward the ways of life that still survive in Abruzzo. To incompetent and often malfeasant government and a dysfunctional national economy, add the relentless drive of mindless development, the dingbat unconscionable belief in unending capitalist expansion. The lucre-worshiping swine driving this discredited idea of progress have pushed to drill for oil along the region’s pristine southern coast, risking to forever destroy a stretch of the Adriatic where the beaches are “Bandiera Blu” (“Blue Flag,” judged perfect and clean for swimming and, obviously, marine life). They’ve tried to build biomass centers in the Comune of L’Aquila, near the very epicenter of the 2009 quake. Others, with the support of corrupt governments, have tried to open the region to fracking. Fracking. In Abruzzo. One of the most infamously seismic regions on a peninsula prone to earthquakes. Where the capital city and its surrounding towns all still bear the scars of recent quakes. And yet the desperate desire for profit has some suggesting an activity that exacerbates the issue. It’s madness. And, of course, we have the fools who think that paving over parts of the national parks is the path to economic viability. To create what? Office parks? Industrial zones? Take Abruzzo’s greatest asset, the element that’s earned the region the title as Europe’s greenest, the very thing that - for the health of the planet, for our own survival- we need more of, and bury it in macadam and reinforced cement. The bloody punishments I’d like to mete out to these greedy, soulless bastards are beyond my powers of description. But that they are criminals, much worse than common thieves, I’ve no doubt.

So what the hell am I trying to say? Well, with certain caveats, I urge you to go. Again, Abruzzo needs – desperately - a discreet tourism comprised of people capable of appreciating its unpolished treasures. The salumi, cheese, olive oil, and wine producers, farmers, artisans, medieval borghi, towns holding on passionately to traditions, and national and regional parks need an infusion of dollars and euro to survive. We might be in late-stage capitalism, but commerce still - unfortunately, in my opinion - feeds the sheepdog. Just don’t expect or exclusively seek out destinations that have cracked the code regarding what it is Americans and other high-end travelers want. Go with an open mind, a desire to experience rhythms and activities outside your normal comfort zone. Driving, staying in small towns, hiking, just looking out of your fucking hotel window will expose you to scenery of indescribable beauty, but - as much as you can - don’t experience it all through the 3x6-inch aperture of your phone. You won’t capture it, and in the trying you’ll miss really seeing and being present for it. This also goes for village life. Try to slow down and adopt the local pace. Turn the damn device off and be in the moment. Listen. Sit quietly in the piazza. Sta zitt’! You’ll be enormously rewarded. Abruzzo’s quiet can fill your head and heart in surprising, ineffable ways.

As far as dining goes, by all means - if you’ve the urge and requisite scratch - go to Reale, Niko Romito’s 3-Michelin Star restaurant in Castel di Sangro, his hometown. It’s a remarkable place highlighting some of the region’s best ingredients. Located in a re-imagined and augmented farmhouse with vast, white, spartan interiors, nothing distracts from the food. And the cooking’s ballsy as hell. His spaghetti cooked only in the liquid drained from local tomatoes is revelatory. So simple, like much of his cuisine, it leaves nowhere for a chef to hide. It’s a worthwhile experience. But not a typically Abruzzese one. For that, you’re more on target at a tiny, menu-less trattoria being served by the cook’s adolescent daughter or at a roadside arrosticini shack. Hole-in-the-wall joints and simple family trattorie are probably the most illustrative of the regional character. Abruzzo, after all, is a region of working people, farmers, and shepherds. You will eat well in these unheralded places, too. And if, by some fortuitous twist of fate, you find yourself in some grandmother’s kitchen watching her prepare a simple, mid-day pranzo, you’re as close to the regional soul as you’ll ever be. You’re in fucking heaven, in my opinion. But if chef-driven stuff is what floats your boat, there’s more than just Romito’s joint. For just a few examples, try Daniele Zunica’s place in Civitella del Tronto, the Moscardi’s Elodia in Camarda, Villa Maiella (1 Michelin Star) in Guardiagrele, L’Angolino da Filippo in San Vito Chietino, La Bandiera in Civitella Casanova (1 Michelin Star), La Corniola in Pescocostanzo, and the relatively new Anima in Introdacqua. All these places (and some others) offer varying degrees of the high-end dining experience some people seek. More importantly, they’re all deeply rooted in the region and their communities, and usually the products of generations of family tradition.

And then there are the less formal places, where Cathy and I most often satisfy our jones for the real deal, where we find the rustic stuff, prepared with understanding, imagination, high skill, but little fuss: Clemente Maiorano’s eponymous restaurant (Michelin Bib Gourmand) in Sulmona; the simple elegance of Sapori di Campagna, just outside of Ofena; Zenobi, in Colonnella, in Teramo province’s Controguerra wine country (where you’ll also find Emidio Pepe’s famous winery); La Sosta in Torano Nuovo, also in the Controguerra zone; Convivio Girasole and La Bilancia in Loreto Aprutino; La Font’Artana in Picciano; La Taverna de li Caldora in Pacentro; and too many others to list here. It’s harder to eat poorly in Abruzzo than it is to eat well.

There are also places where a tourist can book a room, embed, and drink and eat up some actual familial experience. For example, Nunzio Marcelli’s La Porta dei Parchi (which has an “adopt a sheep” program, in which your money pays for the upkeep of a sheep through the year and, in return, you receive cheese and other products) and Gregorio Rotolo’s Valle Scannese, the farms from which we source most of the cheeses used at our restaurant and situated at opposite ends of the Sagittario gorge WWF Reserve. Both are family concerns continuing centuries-old farming and pastoral traditions and producing artisanal products to boot. They ain’t pretty in a postcard way (the farms, that is…the surrounding countryside is crazy beautiful), but they’re real, and they’re doing things the right way. You can even volunteer at La Porta, helping them tend the fields and learning how to make cheese. There’s Pietrantica, on the Majella in the tiny village of Decontra, where Marisa will cook you the true cucina povera (often employing rare indigenous grains like solina). Her husband Camillo, an expert mountain guide, can take you into the mysterious and beautiful Orfento canyon where you’ll visit the caves of brigands, shepherds, and medieval hermits, including hollows used by Pietro da Morrone, who became Celestino V, Abruzzo’s only Pope. If you’re lucky, Camillo’s dad Paolino, who lived his life on the Majella, survived German occupation during WWII, and wrote a book of his experiences as a farmer and shepherd, will sit down at dinner with you and tell stories from a past that, in Decontra, doesn’t seem all that long ago.

Finally, if you’re a tourist or a journalist, give Abruzzo the time it deserves (especially if you’re the latter). Or at least as much time as you can give. Speed-dating the region, as many seem to do, driving in from Rome for or a few hours or a day, can make for missed opportunities and shallow observations. You can have a great experience spending a day in Abruzzo. You’ll eat and drink very well, see some extraordinary countryside and wilderness (at least from your car), and maybe encounter some singular, artisanal products. But you won’t have “discovered” or understood the place, allowed it to penetrate your consciousness. It’s only a couple of hours from Rome, but often seems a world away. Abruzzo, particularly - but not exclusively - in its mountains, offers lessons about community (no one survives without working together), hospitality (warm, heartfelt, often unguarded), and living or trying to live in harmony with nature. And that last one is, I think, pretty damn important. A lot of us talk a great game about doing the right things, supporting sustainable farming and the natural and humane production of our meats, reducing our footprints, etc. We are conscious of climate change and advocate for policies to ameliorate the (possibly already hopeless) situation. In Abruzzo’s parks – where there are still wolves, Italy’s largest bear population, chamois, and dozens of other species hard to find elsewhere on The Boot – humanity’s attempts to live in concert with nature are very much on display. It’s also a battleground, because not everyone’s on board and some territory’s in danger or already lost. But the lesson you learn - if you bother to look and take the time to talk to the people courageously engaged in the fight – is that doing the right thing is rewarding but also fucking hard. Life in Abruzzo’s mountains can seem beautiful. But it’s not luxurious, idyllic, or comfortable. It’s a daily struggle, and maybe a window on how we’re all going to have to attack the problems and forces threatening our survival. No, we don’t all live in the Apennines dealing with limited and shitty roads, crazy weather, the gifts but also indifferent cruelty of nature, and the constant plotting of avaricious, malfeasant agents of “progress.” But, if we’re going to try to turn around and right this badly listing ship, we’ll have to make sacrifices, bite bullets, do without, bloody some noses, and work our asses off. It’s an uncomfortable fact. And a scary one, if you really consider it. Abruzzo is a place that shows us – vividly, vibrantly, and without gloss – that doing the hard work is worthwhile, that the intrinsic values of seeking harmony with our surroundings far outweigh any shallow luxury. Learning that lesson is worth your time.

0 notes

Photo

“In the year of the Incarnation of the Savior 1089, Count Roger took a new wife, his former one, Eremberga, daughter of Count William of Mortain, having died. Her name was Adelaide and she was the niece of Boniface, that most renowned marquis of Italy; to be precise, she was the daughter of Boniface’s brother. She was a young woman with a very becoming face.”

Goffredo Malaterra, The Deeds of Count Roger of Calabria and Sicily and of his Brother Duke Robert Guiscard, book 4, ch. 14

Adelasia (or Adelaide) was born around 1074 in Northwestern Italy. Her parents were Manfredi (or Manfredo) Incisa del Vasto, a member of the Aleramici House, and his unnamed wife. From her paternal side, she was the niece of Bonifacio, Marquis of Savona and of Western Liguria, “the most renowned marquis of Italy” (in Goffredo Malaterra, The Deeds of Count Roger ..., book 4, ch. 14). Adelasia had a brother, Enrico, and two unnamed sisters.

Following their father’s tragic death (killed together with his brother Anselmo during a popular uprising in 1079), the siblings were entrusted to the guardianship of their uncle Bonifacio, although quite soon Enrico decided to travel all the way to Southern Italy to help the Norman leaders Robert and Roger Hauteville in their conquest.

The Aleramic scion was gifted with the counties of Butera and Paternò for his services. But the del Vasto family fortunes were destined to grow as Enrico’s sisters married into the newly established Hauteville comital dynasty. His unnamed sisters were betrothed to the Great Count Roger’s bastard sons Goffredo (who would die young without getting the chance to marry) and Giordano, while Adelasia married the Great Count himself.

In 1089 Roger was at his third marriage. His first (and beloved) wife Judith d'Évreux had given him only daughters before dying in 1076. The following year, he married Eremburge de Mortain, who bore him his first legitimate son, Malgerio, and died in 1089. With just a son (who would die young around 1098) as heir, it isn’t surprising Roger remarried. The choice of an Italian wife (his previous ones had been fellow Frenchwomen) was part of the Hautevilles’ strategies to latinize Southern Italy by welcoming Gallo-Italic immigrants with the hoped result to counter the already existing Greek-Arabic majority.

Adelasia would bore Roger two sons: Simone (born in 1093) and Ruggero (born in 1095 – although Malaterra records “in the year of the Incarnation of the Lord 1098, Countess Adelaide became pregnant again by Count Roger” in Goffredo Malaterra, The Deeds of Count Roger ..., book 4, ch. 26) and at least one daughter: either Matilda (born between 1093-1095, future Countess consort of Alife) or Maximilla (birth date unknown, future wife of Count Palatin Ildebrandino VI Aldobrandeschi), or perhaps both of them.

The Great Count died on June 22nd 1101 in Mileto (Calabria). Following her late husband’s wishes, 27-years old Adelasia assumed the regency of the county for her 8-years old son, Simone, who became the new Count of Sicily. She smartly surrounded herself with capable and trusted men, like her brother Enrico, or Christodulos, a Greek Orthodox (possibly a Muslim convert) admiral who had been nominated amiratus (Grand Dignitary) of Sicily already under Ruggero I.

Little Count Simone’s rulership was tragically shortlived as the child died in Mileto, on September 1105, at just 12 years old. He was succeeded by his younger (and, according to the sources, better-suited) brother, Ruggero. As the new Great Count was even younger (10 years old), Adelasia resumed her role of Regent. It is in this period, precisely in 1109, that the Warrant of Countess Adelasia, Europe’s oldest known paper document, was issued.