#Karuk Tribe

Text

If you aren't following the news here in the Pacific Northwest, this is a very, very big deal. Our native salmon numbers have been plummeting over the past century and change. First it was due to overfishing by commercial canneries, then the dams went in and slowed the rivers down and blocked the salmons' migratory paths. More recently climate change is warming the water even more than the slower river flows have, and salmon can easily die of overheating in temperatures we would consider comfortable.

Removing the dams will allow the Klamath River and its tributaries to return to their natural states, making them more hospitable to salmon and other native wildlife (the reservoirs created by the dams were full of non-native fish stocked there over the years.) Not only will this help the salmon thrive, but it makes the entire ecosystem in the region more resilient. The nutrients that salmon bring back from their years in the ocean, stored within their flesh and bones, works its way through the surrounding forest and can be traced in plants several miles from the river.

This is also a victory for the Yurok, Karuk, and other indigenous people who have relied on the Klamath for many generations. The salmon aren't just a crucial source of food, but also deeply ingrained in indigenous cultures. It's a small step toward righting one of the many wrongs that indigenous people in the Americas have suffered for centuries.

#salmon#dam removal#fish#animals#wildlife#dams#Klamath River#Klamath dams#restoration ecology#indigenous rights#Yurok Tribe#Karuk Tribe#nature#ecology#environment#conservation#PNW#Pacific Northwest

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

Indigenous People's Day

DR. HENRIETTA MANN

Cheyenne

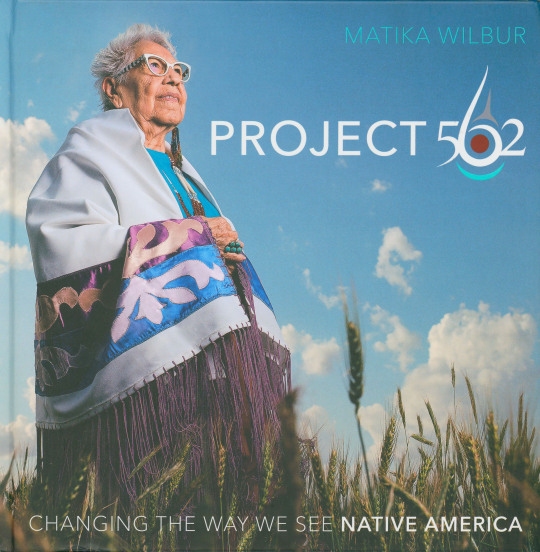

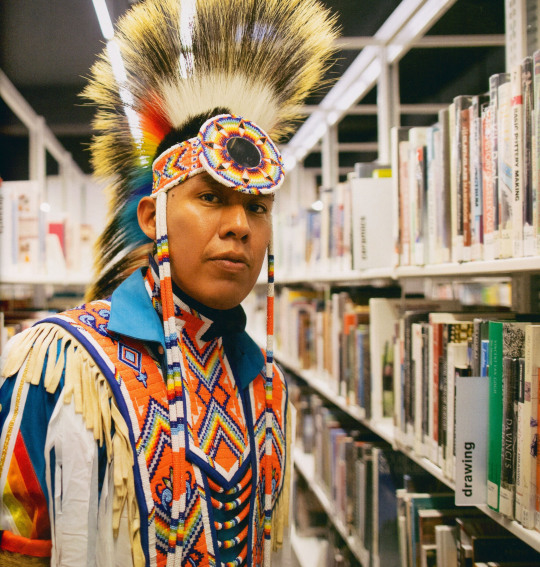

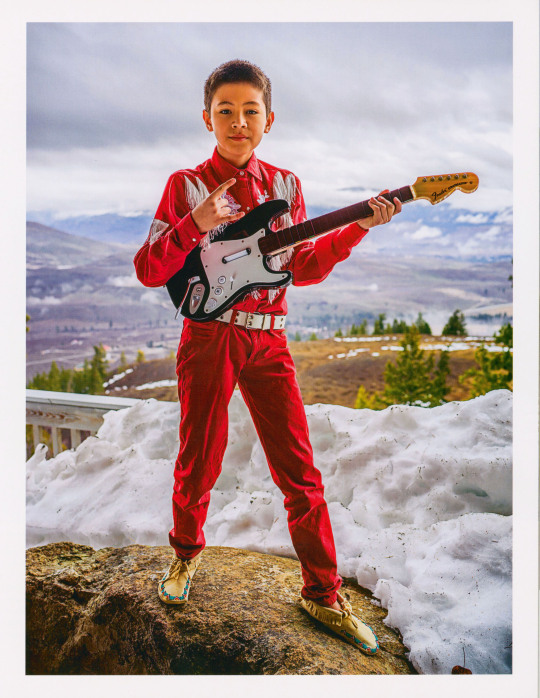

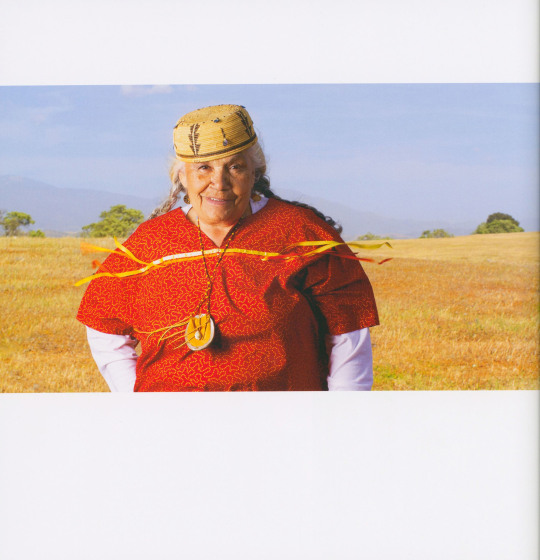

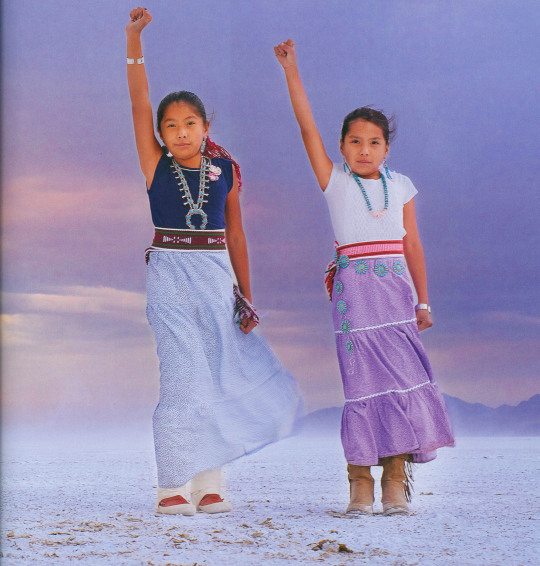

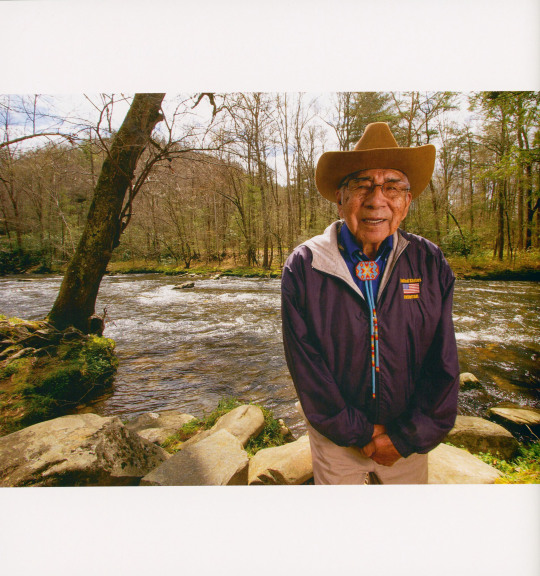

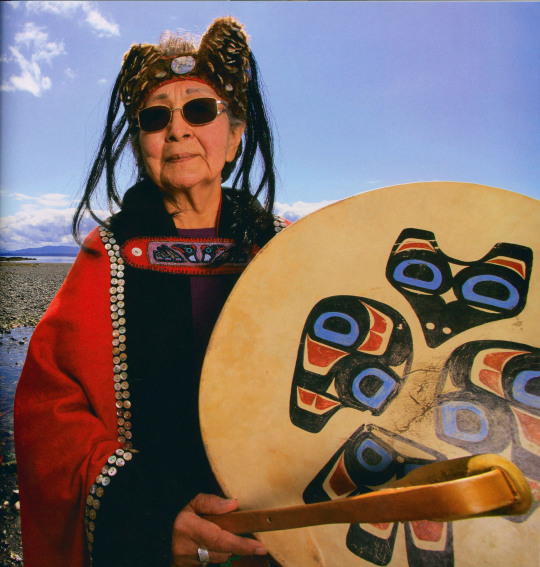

On this Indigenous People’s Day, we are featuring Matika Wilbur’s recent publication Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America, published by Ten Speed Press in 2023. Wilbur (b. 1984) is a visual storyteller and member of the Swinomish and Tulalip peoples of coastal Washington. She holds a degree from the Brooks Institute of Photography alongside a teaching certificate that has shaped her style of educating through narrative portraits.

Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America, a book born from a documentary project of the same name, resolves to share contemporary Native issues and culture. In 2012 Wilbur set out from Seattle to visit and photograph all 562 plus Native American sovereign territories in the United States.

Wilbur’s engagement with the communities she visited resulted in the creation of hundreds of dynamic portraits and documentation of conversations about “tribal sovereignty, self-determination, wellness, recovery from historical trauma, decolonization of the mind, and revitalization of culture.” She refers to her portraiture approach as “an indigenous photography method” that includes several hours and sometimes days of interaction with the participants, an exchange of energy and gifts, and asking sitters to choose their portrait location. The outcome is a stunning collection of Native narratives and portraits.

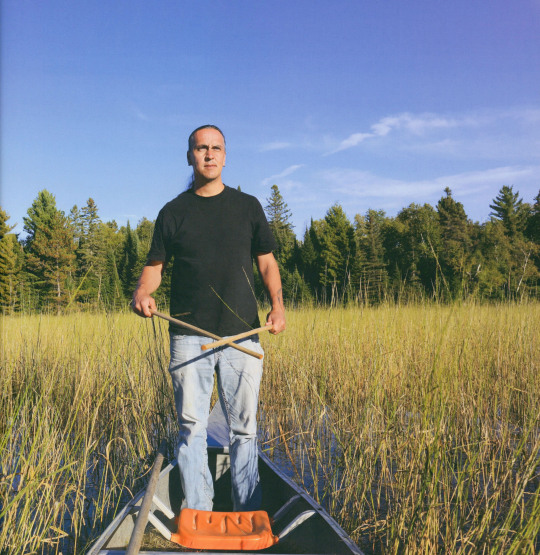

GREG BISKAKONE JOHNSON

Lac Du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

HOLLY MITITQUQ NORDLUM

Iñupiaq

J. MIKO THOMAS

Chickasaw Nation

MOIRA REDCORN

Osage, Caddo

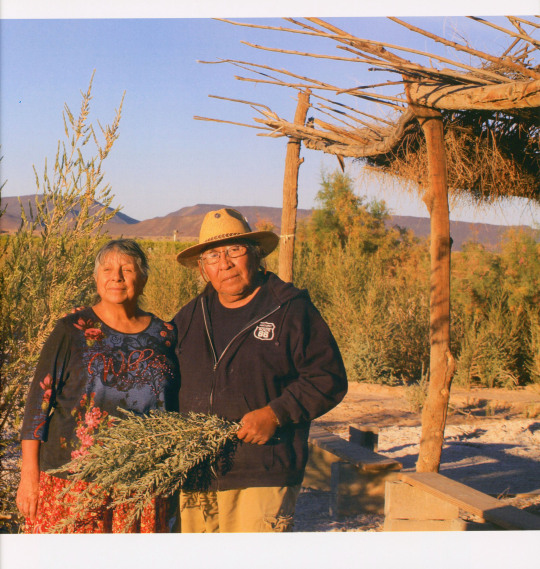

HELENA and PRESTON ARROW-WEED

Taos Pueblo/Kwaatsaan, Kamia

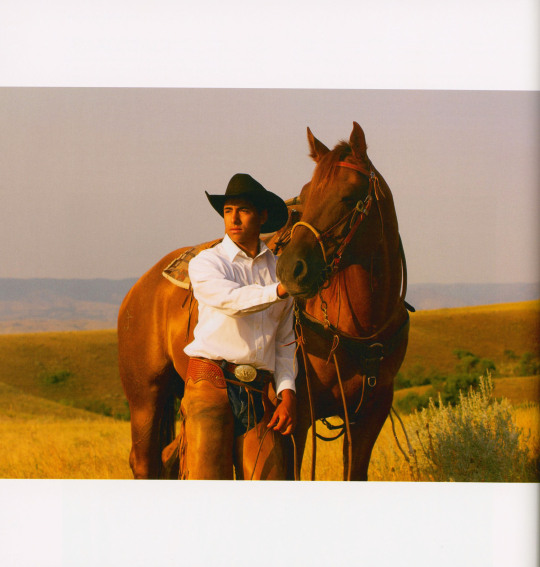

STEPHEN YELLOWTAIL

Apsáalooke (Crow Nation)

LEI'OHU and LA'AKEA CHUN

Kānaka Maoli

ORLANDO BEGAY

Diné

KALE NISSEN

Colville Tribes

GRACE ROMERO PACHECO

Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians

ISABELLA and ALYSSA KLAIN

Diné

NANCY WILBUR

Swinomish

DR. JEREMIAH "JERRY" WOLFE

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

RUTH DEMMERT

Tlingit

MARVA SII~XUUTESNA JONES

Tolowa Dee-Ni' Nation, Yurok, Karuk, Wintu

Matika Wilbur will be speaking on UW-Milwaukee's campus Thursday, November 16 from 6-7p.m. in conjunction with her exhibition Seeds of Culture: The Portraits and Voices of Native American Women on view at the Union Art Gallery November 16 through December 15, 2023.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

We acknowledge that in Milwaukee we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands along the southwest shores of Michigami, part of North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#indigenous people's day#matika wilbur#project 562#Ten Speed Press#Native Americans#holidays#UWM Native American Literature Collecton

810 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Indigenous Peoples' Day from the California State Library! This photograph from the Siskiyou County Historical Society shows a Karok (Karuk) Native American White Deerskin Dance (World Renewal Ceremony) in the early 1900s. The Alliance for California Traditional Arts writes, "The Karuk Tribe is now one of the largest and most geographically dispersed indigenous groups in California... The ancestral territory of the Karuk Tribe includes most of Siskiyou County and the northeastern portion of Humboldt County in Northern California." From our online catalog.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tribes, environmentalists and their allies celebrated the shrinking waters as an essential next step in what they say will be a decades-long process of restoring one of the West's largest salmon fisheries and a region the size of West Virginia back to health.

Yurok tribal member and fisheries director Barry McCovey was amazed at how fast the river and the lands surrounding the Copco dam were revealed.

"The river had already found its path and reclaimed its original riverbed, which is pretty amazing to see," he said. The 6,500-member tribe's lands span the Klamath's final 44 miles to the Pacific Ocean, and the Yurok and other tribes that depend on the Klamath for subsistence and cultural activities have long advocated for the dams' removal and for ecological restoration.

Amid the largest-ever dam removal in the U.S., rumors and misunderstandings have spread through social media, in grange halls and in local establishments. In the meantime, public agencies and private firms race to correct misinformation by providing facts and real data on how the Klamath is recovering from what one official called "major heart surgery."

But while dam removal continues, a coalition of tribes, upper Klamath Basin farmers, and the Biden administration have struck a new deal to restore the Klamath Basin and improve water supplies for birds, fish and farmers alike.

...

The Yurok Tribe also contracted with Resource Environmental Solutions to collect the billions of seeds from native plants needed to restore the denuded lands revealed when the waters subsided.

The company, known to locals as RES, took a whole-ecological approach while planning the project. In addition to rehabbing about 2,200 acres of land exposed after the four shallow reservoirs finish draining, "we have obligations for a number of species, including eagles and Western pond turtles," said David Coffman, RES' Northern California and Southern Oregon director.

...

The company also plans to support important pollinators like native bumblebees and monarch butterflies and protect species of special concern like the willow flycatcher. And, Coffman said, removal of invasive plant species like star thistle is also underway. In some cases, he said, workers will pull any invasives out by hand if they notice them encroaching on newly planted areas.

...

The Interior Department announced Wednesday that the agency had signed a deal with the Yurok, Karuk and Klamath Tribes and the Klamath Basin Water Users Association to collaborate on Klamath Basin restoration and improving water reliability for the Klamath Project, a federal irrigation and agricultural project.

An Interior Department spokesperson said the agency had been meeting with river tribes and the farmers of the Upper Basin for the first time in a decade to develop a plan to restore basin health, support fish and wildlife in the region, and support agriculture in the Upper Basin.

"We're trying to make it as healthy as possible and restore things like wetlands, natural stream channels and forested watershed," the spokesperson said. He likened it to keeping the "sponge" wetlands provide to store water wet. The effort is meant to be a cross-agency and cross-state process.

The Biden administration also announced $72 million in funding for ecosystem restoration and agricultural infrastructure modernization throughout the Klamath Basin from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It’s a great day for the Karuk Tribe,” Attebery said in a news release. “We have taken a huge step forward in protecting our culture and religion for generations to come.”

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wax & Wane / Bryan David Griffith, 2018

Smoke accumulated in encaustic beeswax on panel.

"Many tribes across the Pacific west consider fire as medicine, and as such, view traditional burning as a human service to ecosystems. Prescribing fire in specific areas fosters and enhances water, food, materials, medicines, and vegetation that benefits both people and the environment. Conversely, many landscapes that have experienced the cessation of tribal fire stewardship practices, fire suppression and exclusion, or in simpler terms, not enough fire - are sick, as are the people who live there, from a tribal perspective. Eventually, these places experience too much severe fire, like an overdose.

Cultural-based fire stewardship is central to many tribal lifeways. Traditional Fire Knowledge carried out by tribal communities is the sophisticated application of fire, 'prescribing' fire like a medicine, to promote healthy and resilient landscapes and human communities."

-Karuk descendant Frank Kanawha Lake, Research Ecologist, USDA-Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station

photo captured and accompanying caption transcribed from "Rethinking Fire" exhibit at the World Forestry Center in Portland, OR

#bryan david griffith#rethinking fire#world forestry center#fire art#smoke art#ecology#forestry#forest stewardship#pnw gothic#pacific northwest#pacific southwest

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

(nodding at your tags) I also felt the Native American Lois design looked off but didn't want to speak over someone who could be more informed than I am, but I've seen Native people talk about character design and,,,I am so doubtful the MAWS crew consulted any Native people on that design lol especially when it ends on thanksgiving anyway

I'm Karuk, and really really interested in other tribe's history of clothing and bead making. I'm no expert by any means, so *maybe* I could be wrong about the dress. But the feather is basically the biggest red flag there is. Feathers are reserved for special occasions. There are specific ways they're handled and worn. They're not just an accessory you can throw onto a design, they have a Purpose.

It's literally such a spit in the face. Going to such big lengths to show all these different designs and cultures of Lois and then just ending the episode on Thanksgiving of all things. How tone deaf do you have to be. The back-peddling is Astronomical. And like you said they're really just appealing to a certain kind of white audience.

#they want their pat on the back and then move on#No I don't Particularly care for maws at all and am tbh immensely disappointed (and somehow not surpised) at how it's turned out#but sure lets make clark a 'goofy softboy himbo' or whatever other trope word salad people are throwing at him#and lets make Lois............ whatever the FUCK you'd call her. hashtag Girlboss or some shit.#don't even get me started on Jimmy we all know he's. they massacred my boy. they just fucking. ruined him.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nature: How Native American Traditions Control Wildfires

As wildfires escalate in Western states, authorities are embracing once-outlawed burning practices.

— By Alissa Greenberg | Friday April 14, 2023

Crews manage a low-intensity fire to burn ground fuels and create a "black line" to help contain a wildfire in New Mexico's Gila National Forest in May 2012. Image Credit: Kari Greer, USFS Gila National Forest

In September 2020, the Slater fire roared through the tiny northern California town of Happy Camp, destroying almost 200 homes. Like many of the megafires that have increasingly engulfed the state, the fire burned hot and fierce for days, spitting embers miles ahead of itself and rapidly igniting the space in between. It ultimately consumed more than 200,000 acres. “For about a year in that area, you wouldn't see any birds,” Kathy McCovey, a forester and anthropologist from the area, said in an interview for the NOVA documentary “Weathering the Future.” “You wouldn't see any animals, any insects. It was just devoid of life.”

Happy Camp is tucked in the Klamath River Valley, in the traditional homeland of the Karuk people, and it is still home to a significant Native American population. But many residents were forced to move after the fire, afraid of what might happen if they rebuilt. “We'd had fires come close to Happy Camp before, but they didn't burn as intensely or as quickly,” McCovey told NOVA.

Some 24% of California’s forest burned between 2012 and 2021, with blazes like the Slater fire sparking more frequently and putting communities at ever-greater risk. “Even though we have the largest, most well-trained firefighting force on earth, there's simply several months out of the year when no amount of resources are going to stop these wildfires,” Will Harling, director of the local mid-Klamath watershed council, told NOVA.

It’s a painful reality for the Karuk and other Native American groups in this part of California. Their livelihoods and traditions were closely linked to fire for millennia. But after European contact, they were harassed, jailed, or worse for practicing traditions that involved careful maintenance of the land with fire. Now, California and other Western states are seeking a return to those traditional practices as they try alternative approaches to controlling wildfires, a bittersweet victory for the Native Americans who have long fought for the right to burn.

The Klamath River in Northern California, ancestral home to Native American tribes including the Karuk. Image courtesy of GBH

For thousands of years, the Karuk used fire to maintain forests as a source of food, following an annual burning cycle to create an environment that was optimal for the area’s native plants and animals. Some 80% of the species the Karuk have historically relied upon for food, traditions, and rituals cannot thrive without fire, according to Bill Tripp, the Karuk director of natural resources and environmental policy. Those species include willow used for basket weaving; tanoak trees, whose acorns are a major food staple; and elk, an important source of protein. The types of forest meadows created by regular fires are important for elk populations, Tripp told NOVA. “Maintaining these types of places with fire helps to make sure there's more healthy calves, which means there's more healthy adults.” Similarly, a well-timed fire will cause insect-infested acorns to drop to the ground, while leaving healthy acorns unscathed and ready for gathering. And flames prompt willow shoots to grow back straighter, more pliable, and better suited for weaving.

“Our place in the world is to manage our piece of the world,” Chook Chook Hillman, a Karuk community organizer and cultural practitioner, told NOVA. "That's part of the reciprocity that has allowed us to live here for so long.”

But starting in the 1800s, White settlers arriving in the area saw these forests as a source of income and worried that their new towns were vulnerable to the fires that occasionally swept through. One of the first laws after the establishment of the state of California banned intentional burning. “Native people in this place were shot and imprisoned and beaten for trying to maintain their cultural fire practices,” Harling said. Those practitioners who continued Karuk burning traditions risked legal trouble to do so until as recently as the 1990s. McCovey recalled hiding her fire practices even from friends, mindful that they might land her in jail.

Without regular, low-intensity fires to thin them out, California forests are now twice as dense as they were 200 years ago. “Everything’s dead underneath there because every tree is wall to wall,” Hillman said. “All you have is this brown layer of branches and needles. It's just this bed waiting to really explode.” Add to that the increased drought and heat wrought by climate change, and you get the conditions that produce the megafires that have plagued the West for the last decade, turning what was once a fire season into what Harling refers to as a “fire year.”

The Karuk Tribe's Tishaniik ceremonial site, which was maintained by prescribed burning. Image courtesy of GBH

With infernos like the Slater fire becoming the norm, many areas in California are turning toward purposeful burns like those the Karuk practiced for millennia, recognizing that, as Harling said, “it’s how you want your fire. Do you want your fire in the middle of the fire season as an uncontrollable wildfire? Or do you want to put it in intentionally?”

In much of the West, that has meant mixing what’s known as “cultural fire," with a ritual focus, and “prescribed burns” that incorporate more Western fire science and data. Tripp, like many cultural fire practitioners, was raised on stories and oral tradition, which taught him how to burn complex fires from a young age. “We didn't have electricity, running water, refrigeration, all that kind of stuff when I was little,” he said of his childhood with his great-grandmother, “but I learned how to read the environment, how to know when this is going to burn, but this over here isn't.” This new era allows Tripp and others like him to return to those practices with less anxiety about the consequences.

One goal in this approach to fire is to achieve a kind of burned mosaic, Hillman said, a patchwork in which some areas are more deeply burned while in others only grasses or undergrowth are singed, clearing fuels away but leaving the forest canopy untouched. Karuk tradition even includes guidance about the ideal timing to burn around specific plant species.

Meanwhile, prescribed burns tend to apply this approach to more generalized fire management that’s not for explicit cultural or ritual purposes. At a recent prescribed burn near Happy Camp, community members helped lay down a “black line,” a border of burned greenery meant to stop the advance of a wildfire that might come through or a prescribed burn that might burn out of control. That created what practitioners often call a “catcher’s mitt” or “safety net,” a burned buffer zone useful for protecting communities and controlling future prescribed fire.

With that safety zone in place, they lit fires across a field, keeping a close eye on the level of moisture in the air and the speed and direction of the wind. Water hoses waited nearby to help put down any flames that might leap across the black line. With any fire, escape is a concern, but careful planning allows for burning when the risk is minimal. “What we know is that the relative risk of being organized ahead of time, of choosing your burn window and choosing your resources, is night and day from the situation in a wildfire, when it's coming at the hottest, driest day of the year,” Harling said.

Chook Chook Hillman (left) and his father Leaf Hillman (right) walk through the Karuk Tribe's Tishaniik ceremonial site, an area maintained by burning. The U.S. Forest Service made headlines in 2022 when a planned burn in New Mexico got out of control. But only .5% of prescribed fires in California escape, and even then those rarely cause severe damage, since they tend to take place when conditions are less volatile. Image courtesy of GBH

In 2021, the U.S. Forest Service burned nearly 2 million acres of federal land in prescribed fires, more than ever before. And it has promised to continue expanding the practice, managing more than 50 million acres with fire over the next decade. That’s a meaningful shift for Native American fire practitioners like Tripp, who are able to reclaim their tradition and bring “good fire” back to the mountains.

To start, Harling, Hillman, and others are focusing on more intensively managing existing wildfire footprints, like the ruins of the Slater fire. “It’s an opportunity without any major fuels built up to start to put fire back in as those pieces of that landscape become receptive, so that you immediately get that patchwork of frequent fire,” Harling said.

As California looks to a climate-altered future, Tripp echoes Harling in emphasizing the fire-dependent nature of the state’s ecosystems. “The fact is, it's going to burn under the conditions that we choose for it to burn in, or it's going to burn in the conditions that nature or a careless match or cigarette butt or power line transformer decides,” he said. That means that part of the task of managing California fire is changing the population’s relationship to it.

In Happy Camp, both the Native and non-Native communities have engaged in intensive discussions about how to use cultural and prescribed burns better and more frequently. And in recent years, local students have begun visiting sites before and after prescribed burns to understand the process and observe the health of various species. Some have also started attending the prescribed burns themselves, to start getting used to what it’s like to be around flames again. “Fire can be your friend if you can learn to understand it,” Tripp said.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pacific Salmon Will Regain Access to Hundreds of Miles of Spawning Grounds as Historic Dam Removal Gets Green Light

YaY!! 🐟🐟🐟🐟

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Im working on a paper about cultural burning/good fire/fire stewardship in relation to native Californians and holy shit is it hard to find actual historical accounts/descriptions of what specific tribes did. I have brief descriptions of shit the Karuk and Yurok did, just found stuff on the Coast Miwok, but im really struggling to find anything else. Especially in relation to when cali literally banned the practice

0 notes

Quote

MARK BRANSOM: For the first time, you know, in a hundred years, beginning today, the river is actually coming back to life.

NEUMANN: The Klamath River flows more than 250 miles from Oregon through far Northern California, where it joins the Pacific Ocean. But for decades, much of the river has been blocked by four hydroelectric dams. Several tribes up and down this river have been at the forefront of protests to remove them for the health of fish, including salmon. Amy Cordalis is a member of the Yurok Tribe and a longtime advocate for dam removal.

AMY CORDALIS: This is historic and life-changing, and it means that the Yurok people have a future. It means the river has a future, the salmon have a future.

NEUMANN: Cordalis is an attorney for the Yurok Tribe and one of a younger generation of activists who took up the fight after the pioneering work of older tribal members like Leaf Hillman. He's a member of the nearby Karuk Tribe who helped start the campaign to take out the dams more than 20 years ago.

LEAF HILLMAN: As one generation, you know, moves on and passes on, the new generation is there to pick up the fight. And so it really has been a multigenerational struggle to remove these dams.

NEUMANN: The Klamath was once the third-largest-salmon-producing river on the West Coast. But over the past century, the salmon numbers have shrunk. The dams cut off spawning habitat and created conditions for fish diseases. Scientists are hopeful that ultimately taking out the dams will help the population rebound. Shari Witmore is a biologist with NOAA Fisheries. She helped evaluate the impacts to salmon from dam removal on the Klamath.

Klamath River begins to flow again with dam removal project : NPR

1 note

·

View note

Text

I just keep thinking about how it can actually be incredibly fucking hard to try to do research on your Indigenous family if you're trying to reconnect. When it came to my Métis side, because there's no recognition in any formal sense down here in the states, I didn't really know what anything meant at the beginning. I could see the names of Red River families and then find a map of St Vital where my family lived but then also made some rookie mistakes in thinking everyone on that side was Métis. A lot of the names on there are just French. When I found that out, I stopped saying my Métis names were Larance AND Nadeau because my specific Nadeau ancestor--despite being buried in Teton County Metis Cemetery--is just French. Not hard. There's a wealth of research still available but a lot of documents are in French and I don't understand.

I could go onto groups and be like "Hey this is my family" and they go "Yes, those are Métis people and you are Métis" and is that what it is to be claimed? Do I have to send my research to ST. Boniface to confirm? Do I have to get a card from MMF? Where does reclamation begin and end?

On my Yurok side it has been extremely challenging. There's no paper documentation prior to 1848/1849. The first state census was in 1852. I can go to the Index to the Census of California Indians and see my relatives listed as "Gold Bluff" tribe and then, after a few years of painstaking searching, infer from that knowledge that we are likely from Espeu. I can constantly comb through the 70+ DNA matches and whatever family trees are available to try to string together a hypothesis of how we're related because the genes do not lie, but I cannot actually prove any of them. Maybe if I travel there and talk to people face to face I can come closer but I lost hope years ago that I can solidly prove what village(s) my family is from. I know who some of my relatives are but I cannot explain in detail how we are related because our families were slaughtered. I could hypothesize that we are also probably Karuk because some of those DNA matches have largely Karuk relatives but the only information I know is that we are Yurok.

It has taken me years to even feel comfortable saying I'm Métis or Yurok because of the lack of knowledge. I have more now, and I still struggle. The best research I could do would be in person but that means money, travel, time off from work, and in the case of going north I need an updated passport. I can pull up Youtube to learn how to bead or listen to Yurok in 20 on Spotify. I can try to reframe my access to the internet and the ability to pay for an Ancestry subscription as a privilege even though it is a fucking shadow of what it actually means to learn the culture. All of this could crumble because maybe someday I might form a grudge with someone online who'll do the deep dive and point out the times my Indigenous ancestors were misrepresented on census or whatever.

There is a lot of art and a lot of stories in me that I am aching to create every day that intimately explore my relationship with my race vs my ethnicity vs generational trauma. I'm not sure if I ever will. Every time I try to put it out there I'm terrified because I don't know enough and I never will.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Geneticists Light Up Debate on Salmon Conservation | TS Digest

To the Karuk Tribe, Ishi Pishi Falls on California’s Klamath River is the center of the world. Every spring, a nearby holy site is the location of the first of a set of ceremonies collectively called pikyávish, meaning “fix the world” in the local language, explains Ron Reed, a dip net fisherman and tribal cultural leader who conducted the ceremony for years before passing the mantle on to his…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ranchers who are members of the Shasta River Water Association have defied state law by diverting water flows from the Shasta River, a key Klamath River tributary for imperiled coho and Chinook salmon, a joint press statement from the Karuk and Yurok Tribes revealed.

The Association violated an order by the State Water Resources Control Board Board to cease and desist all diversions from the Shasta River just a week after a fire induced mudslide killed all fish in a 60-mile reach of the Klamath River.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

'Virtually everything in the river died': Tribe says wildfire floods causing thousands of dead fish to wash up along California river

'Virtually everything in the river died': Tribe says wildfire, floods causing thousands of dead fish to wash up along California river

CNN.com - RSS Channel - HP Hero "Tens of thousands" of dead fish have washed up along the Klamath River in the area of Happy Camp in northern California this week -- a phenomenon that's tied to a dangerous combination of flash flooding and the McKinney Fire that's burning in the area, according to Craig Tucker, a policy advocate for the Karuk Tribe. https://ift.tt/YzsfC3P https://ift.tt/ecYIVi3

via Blogger https://ift.tt/KLxufMH

August 07, 2022 at 02:22AM

0 notes