#I made it AS SHORT AS THE SPIRIT OF HAGANEZUKA WOULD LET ME

Text

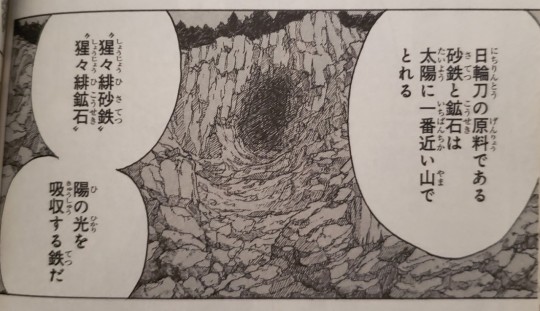

You need a mountain to make a sword

Mt. Youkou, which only exists in the Kimetsu no Yaiba universe is essentially named "Mt. Sunlight," is said to receive the most sunlight, which gets soaked into the Shoujouhi iron ore and Shoujouhi iron sand—both of which also only exist in this universe and are named for a particular shade of red. This mountain is therefore crucial to the development of Nichirin blades, and deserves more focus than a one-time mention in Chapter 9. If demons were to find this place and prevent them from mining, the Corp would be screwed.

A mountain is a finite resource, though. This post was supposed to be short and simple to say:

1. Large portions of that mountain are lost in the effort to collect the sunlight-soaked iron sand

2. Large portions of that iron sand is lost in smelting it into steel

3. Large portions of that steel is lost in the smithing process

But of course, it is not short and simple, I have more to say about charcoal and what this all means within the context of the KnY world and additional speculation about the production of Nichirin blades.

First you need to break the mountain!

Okay, so you start with a mountain. This one is said to be “closest to the sun,” which has made some people theorize that this is the tallest mountain, Mt. Fuji, but perhaps that is just a way of saying it is in a sunny spot in the east. The main criteria is that it is very exposed to the sun. I think the "it doesn't rain" there thing is an exaggeration, as there are trees drawn there, so I assume it has some sort of a water source.

I will focus primarily on collecting the Shoujouhi iron sand as opposed to the ore, because in real life steel smelting in Japan, iron sand was more widely available than ore—and however they got the Shoujouhi ore, I’m guessing it was more of a process of scraping it off exposed parts of the mountain instead of digging deep in the dark for it. It used to be that that iron sand was collected in rivers and lakes from the natural, slow erosion process, but going by the illustration in the manga panel, they appear to practice kanna-nagashi, a process of collecting iron sand in large amounts by speeding up the natural erosion process by scraping off chunks of granite mountain into man-man waterways, and channeling it through a series of collection pools to sort the heavier iron sand from the rest of the sediment. Another reason to suspect this method is because the "Kana" of Kanamori's name is written with the same "kanna" kanji: 鉄穴 ("iron cavity," as opposed to the more common real life last name Kanamori which uses the simple 金 for metal/gold).

In the heyday of real-life traditional iron and steel smelting with iron sand, kanna-nagashi resulted in mountains being leveled because they used up so much of the natural environment. This was used for meeting almost all of the iron and steel needs of populous Edo period society, which did not need as many swords as in previous eras but needed anything from tools and nails to pots and pans. The swordsmiths in Kimetsu no Yaiba only needed to make swords for the Demon Slayer Corp (which we’ll use for referring to the organization’s full history, though it was less formally called “the demon hunters” for most of its existence). The swordsmiths making Nichirin blades were probably frugal with the precious Shoujouhi iron. They needed to make it last for as many centuries as it would take to defeat Kibutsuji Muzan.

Not all iron sand is created equal!

While what's very crucial to Nichirin blades is that the iron that has soaked up the power of the sun, what's also crucial to making Japanese blades is a high level of purity in the iron. To put this in perspective, the more common kind of real-life iron sand (akome) that could be used for general iron needs might make up 5-10% of the rock plucked off the mountain, but masa iron sand, the kind that was (and still is) preferred for making Japanese swords might only make up about 0.5-2%. These sands would differ in size, the amount and array of impurities, and how high of a temperature and how long you need to smelt them. However, the real-world smelting process for making sword-quality steel used a mix of these two kinds of iron sands, so it might be reasonable to assume they stretch out the Shoujouhi iron sand supply by supplementing it with high quality sands from other nearby, shadier mountains. There is also the matter of how much of it was Shoujouhi ore, and how much of that ore was available relative to the sand on this fictional mountain, but I’ll focus primarily on a real-world iron sand based processes for consideration on numbers.

Anyway, we've perhaps already wasted at least 85% of what we've taken from the mountain to get this sand, and then it's time for smelting the Shoujouhi iron sand (and Shoujouhi iron ore, in this case) in a traditional tatara clay furnace, because for most of Japanese smelting history, that was what you had.

Tatara iron and steelmaking made the most of what Japan had!

Smelting iron in clay furnaces did not originate in Japan, but while many other places in the world had more abundant sources of iron ore to start with, Japan did not, so the tatara method was continually development to make the most of what was available: iron sand. Two of the other major ingredients in this method were clay and charcoal, the qualities of which were important in setting off the chemical processes of smelting the iron sand into pig iron (which would be refined into better iron or for steel for making swords). With Edo period developments in this Japanese smelting method, they were able to skip the pig iron step and achieve a sword-quality steel, tamahagane. Tatara is still the only method with which you can achieve tamahagane.

Look at this beautiful sword baby:

(Fun fact: Tamahagane is covered with many different colors—but rather than being indicative of Nichirin-like properties, these are tiny films of remaining impurities in the metal, which reflect light similar to how it bounces off a soap bubble or a CD. Cool, huh? I also tend to theorize that the coloring changing aspect of Nichirin is a matter of bending the visible spectrum of the sunlight contained within them.)

We don't have time here to go into the fascinating details about how this smelting process works and why tamagahane gives you the characteristic attributes of Japanese blades, but suffice to say, what's crucial is that tamahagane has a high level of purity and an ideal amount of carbon for making blades that are both strong and ductile. However, prior to the Edo period development of tamahagane, we don't actually know all the details about the materials used. Swords could vary widely in quality in the Sengoku period, and it's very likely that the high-quality ones (like what the demon hunters would had used) mixed stronger, imported iron with the local iron sand. This is another reason I'm willing to bet Nichirin blades might be reenforced with other material, though it is still entirely possible in-universe that they are purely Shoujouhi and the craftsmanship of the swords back then was purely thanks to the swordsmiths’ efforts.

A quick note here before we go on: historically, it makes the most sense for Tanjirou to have been offered tamagahane at the end of the Final Selection, because this was the standard material for Japanese swords at the time. In Chapter 8, Kiriya does not say “tamahagane,” but just “hagane,” which means “steel.” However, the first fanbook says that they choose their “kouseki,” which is “ore,” implying that this is still in a raw material stage. It’s possible that before the Edo period development of tamahagane, swordsmen were offered their choice of lumps of Shoujouhi ore, but given the speed with which Tanjirou received a completed sword, I’m willing to bet it had already undergone the smelting process with Shoujouhi iron sand in one big smelting batch. Although industrialized methods of smelting steel with mined iron ore, coke, and brick furnaces were already the norm by the early Taisho period, tatara was still in use, and still the only method of making tamahagane, so I am inclined to think the Swordsmith Village stuck with this and used tamahagane (and Japanese fans who are familiar with the tatara process all tend to assume the same, though most of the ones I've talked to about it are biased tatara nerds in the first place).

Charcoal is crucial in tatara and Japanese swordsmithing!

We also don't have time to go into detail about the clay or construction of the tatara furnace, but because this is KnY and I love charcoal, we will touch on that briefly: The charcoal used in tatara would be slightly different from the charcoal Tanjirou produced for household use or the charcoal used in multiple steps of the actual smithing process (both as a heat source and as a coating in a crucial step of the process). In a tatara furnance, it needed to burn quickly and at high enough temperatures to melt iron sand, it was left somewhat "undercooked" in the charcoal making process so as to leave more volatile organic components. Even with those sorts of adjustments to the charcoal making process specifically for tatara, Tanjirou could absolutely talk shop with the Swordsmith Village charcoal producers.

Also, in order to get trees big enough for tatara charcoal use, the trees were ideally 30-50 years old. Forestry methods in tatara charcoal production typically allowed the forest to grow back every 30 years, but this meant they needed roughly 30 different areas to cycle through and cut down from year to year. A single operation of the tatara furnace typically requires about 12 tons of charcoal, that is, roughly one hectare of forest. (This is why industrial tatara in real life usually required owning entire mountains in order to have that much forest available.)

What is one tatara operation?

For our purposes here, suffice to say that a tatara operation for the purposes of making tamahagane is a roughly 70-hour process of adding iron sand and charcoal to the flames every 30 minutes or so, resulting in a 2-3 ton lump of mixed metal, called a kera (which is written with sort of vivid kanji that makes it's like the "mother of metal," 鉧). What adjustments that might require to include Shoujouhi iron ore, I am not sure. It is an extremely labor-intensive process, with a high level of know-how required to be successful. It is very easy for the process to be ruined if the giant flames are not maintained, or the proportion of the materials is off, or if there is too much moisture or not enough constant air flow, etc. It also uses a lot of material. In addition to about 12 tons of charcoal, one operation typically requires about 10 tons of iron sand. Roughly 70% of the resulting kera would be tamahagane. That means, very roughly, that of the 10 tons of iron sand, only 15-20% remains as ideal sword material, but maybe only about 0.3-4% of the overall iron sand turns into top quality tamahagane.

How many swords are we talking?

The Swordsmith Village exclusively made swords for the Corp, which in Tanjirou's day and age is said to be “a few hundred” people (Chapter 4, and given the context, I assume this means “a few hundred swordsmen” as opposed to including outside supporting roles). Tamagahane for a katana is about 4 kilograms, so you can get, conservatively (and this is only my guess based on weight calculations, not on actually numbers of lumps of tamahagane I found results for), about 375 swords worth from one kera, or maybe up to 90 especially high-quality swords. We see anyone from a Mizunoto like Inosuke to a Pillar like Muichirou getting their swords replaced without much fuss, and clearly some styles of Nichirin blades require more or less steel (looking at you, Stone Pillar). The swordsmiths likely also use material for practice and trying new techniques, as well as for having extra swords available like those stocked up in the village.

I'll allow you to think backwards about how much mountain this consumes every year in a Corp that has been collecting ore and sand from Mt. Youkou for 800-1000 years, with the more damaging kanna-nagashi process being used for about 250-300 years. Instead, I will work forward to say that for a typical katana, that 4-kilogram tamahagane results in only a 1-kilogram sword, so you lose material at this stage too.

To recap:

The amount of Mt. Youkou destroyed but which gets collected as iron sand is only about 0.5-15% (if we're being generous). The amount of that iron sand which gets converted into tamahagane is only about 15-20% (or less if they are very stringent about Nichirin quality), though the numbers might be very different depending on the amount of iron ore used. The amount of tamahagane which remains as a finished sword is only about 25%. This is not even taking into account the amount of forest, clay, or even the series of stones necessary for the polishing process, not at all to mention expertise and labor.

So quit breaking your swords, Tanjirou.

Sources:

In modern day, the Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords (NBTHK, or Nittouho) operates the Nittouho Tatara furnace three times every winter, so most of these numbers are based on their modern-day operations (though they do not practice kanna-nagashi, which was primarily practiced in the Edo period when tatara was a major industry). Other info primarily comes from other tatara related museums, especially the Okuizumo Tatara and Sword Museum and Wakou Museum, though it’s been glossed over for fandom purposes. Also, I’m a sword nerd anyway.

#SWORDS SWORDS SWORDS#KnY nerdery#KnY Reference#KnY References#I made it AS SHORT AS THE SPIRIT OF HAGANEZUKA WOULD LET ME

62 notes

·

View notes