#I built my house at the end of a massive cavern with a big lake

Text

sometimes I get a sudden and violent craving for the minecraft server I played when I was 12 as if I could log on and play it whenever I want but girl that was over a decade ago...

#I built my house at the end of a massive cavern with a big lake#you had to take a boat to get to the house#I built an automatic carrot farm in a rocky overhang in the ceiling#I had a little horse ranch and was working on building a great cobblestone wall around my property#my first ever horse was named Dynamo and to this day whenever I play minecraft I aim to get a horse with the same colors and name it Dynamo#the server had an urban area by the spawnpoint which was kind of fun#I never see that in modern minecraft servers#like it had The City (player built) that was this big urban area in the center#The City was located by a jungle so ocelots KEPT FUCKING SPAWNING and never despawned so The City was overrun by cats#so I built traps for them and an animal rescue in the city#and routinely checked the traps for cats and brought them into the animal rescue#I miss my minecraft house I never finished my bakery on the other side of the mountain behind my house

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kitsune Shrine, Tori Gate, and Household (Sorta)

This is a big post, cause a lot of screenshots, and I’m going to kinda walk through the whole of it to explain things. All of it’s going to be under a read more post, but that’s more just to keep the dash a little cleaner for everyone.

Since this is all in Minecraft, this is more to just give a general visual of what the place would be like. Things to keep in mind is that, unlike in the images below, the lake which holds the Tori is much bigger, mostly rounded, and takes up the majority of the space of the clearing where the Shrine and the Kitsune Home is. If on a map, the shrine is on the southern end of the lake, and the house is on the south-eastern bank of it.

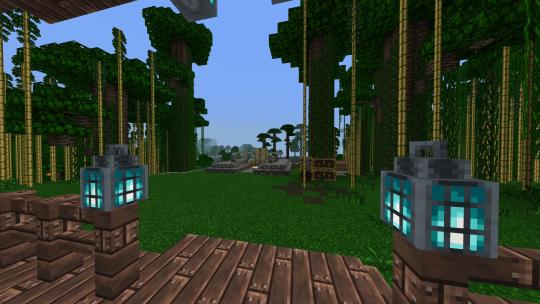

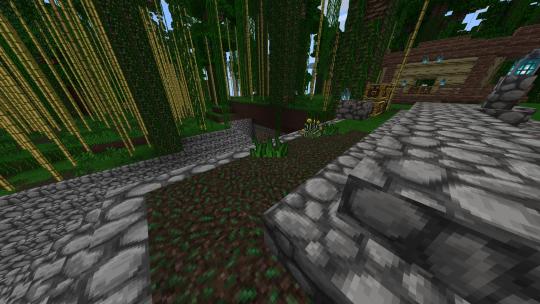

To start with, the land which Kyuushi’s family owns is found amid a large, forested area, where the trees are mixtures of Japanese Cedar Trees, Bamboo, and closer to the Shrine itself are some scattered Sakura trees. The Sakura trees being mostly around the lake which holds the Tori Gate. The first sign that you’re nearing their land is that you start finding bamboo scattered around among the forest, and a rise onto a large hill sometime after. The Bamboo grows denser the closer you get to the shrine proper.

Around the land is a barrier, one which isn’t designed to keep things out completely, anything can pass right through it. The Barrier is designed instead to confuse those passing through it, and to deter them or lead them away from the Shrine. Animals can pass through with little or no issue more due to their natural instincts, and their higher senses. Humans and other sentient beings like Demons, Yokai, or creatures like Dragons, Wyverns, Minotaurs, etc, will be more effected by the barrier, to varying degrees.

The land of the Shrine is meant to be a safe place, mainly for the Kitsune family who has lived there for millennia. Though if people manage to find their way to the shrine, they will be welcome to stay for a short time, given they aren’t hostile. Any hostility will be met with full force, not only of the Kitsune’s living there at the time, but by the spirit of the Ancient Kitsune herself, and all her wrath.

For those who aren’t hostile, however, this will be what they see when first passing through the forest surrounding the Shrine, and out from the thicker Bamboo which acts as a natural barrier:

The Pagoda is a place to stop and rest, to set up smaller, temporary shrines to those who have passed, to hold gatherings with visitors, or for visitors to use as a place to rest for a night or two. It has a sliding door on both the front, and back of it, but they are usually open unless being used for shelter at night. Beyond the Pagoda, after passing through it, will be the sight of the Shrine to the Ancient Kitsune herself.

The Pagoda, like all constructions within this land, has many lanterns filled with ethereal flames which light it eternally, and ward off unfriendly spirits, as these flames are fragments of the Ancient Kitsune’s soul. These will brighten, and the fires within will seep out of the small gaps in the lanterns when the spirit is angered by hostile entities that dare tread upon the land. They also naturally dim at night, allowing easier rest for those who reside here.

I did my best to try and recreate the shrine designs from Ghost of Tsushima here, which has been praised for it’s visual accuracy of Tsushima itself. A stone altar around wooden Shrine with a sand center to allow more comfortable kneeling during prayer. The Shrine sits at the inner most point of the large hill that the whole site sits atop, overlooking the descent into the hill’s center where the lake fills, and the Tori Gate sits at it’s center.

The Tori Gate itself is large, made with pale, ashen colored wood unlike the red of most others. It sits in the very center of the large lake that fills an almost crater-like space in the center of the massive hill where this site is located. There is no walkway to reach it, and use of a boat will not allow travel through it. Kitsune’s are able to “walk upon the water” through use of one of their base magicks, condensing their magic energies beneath their feet to provide unseen platforms where they can walk. If strong enough, they can provide enough unseen footing for two others to walk by their side with them.

The Tori itself, as stated, is found at the center of the lake, with the Kitsune’s Home sitting on the south-eastern bank atop a beach-like portion of the lake’s shore. The lake does have a river feeding water into it from a nearby mountain, and a river which flows out from it, and towards the sea. The waters of the lake itself are clean, pure waters after passing through the barrier that surrounds the land. Many different kinds of aquatic life calling the deep lake their home, birds frequently bathing in it, and animals of the forest drinking from it often.

The home itself is extremely old fashioned, having been built long, long ago. It is kept in good condition thanks to charms and enchantments that have been placed upon it, allowing it to last as long as the family has. It’s rather small, but considering the family itself has remained relatively minimal in number, it works plenty enough.

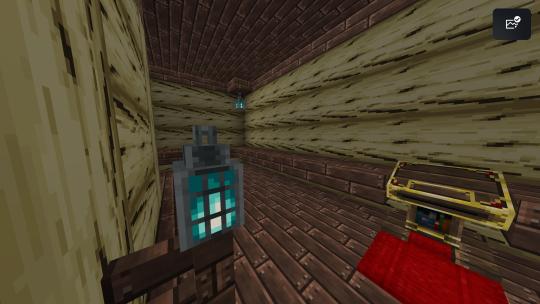

Past the first doors is a small foyer, where outter-wear like shoes, sandals, and coats are normally kept. There’s not much in minecraft I could use to represent it, but there is a cabinet in both the farthest corners from the entrance, to the left and right of the door that leads into the rest of the home. The left side contains cooking supplies, as most all meals that require cooking are done over fires on the beach itself. The right side contains dinning implements, plates, bowls, utensils, cups, etc.

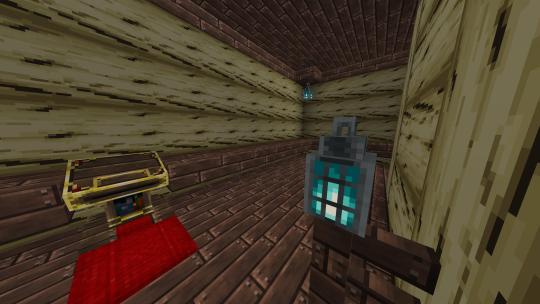

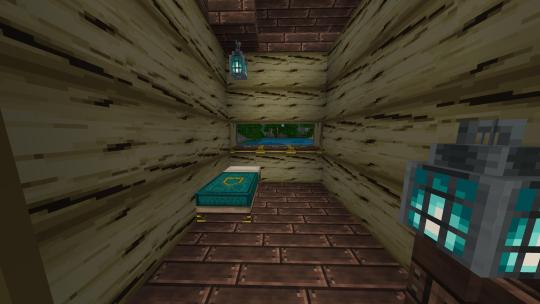

Past the second door within the home, the first sight anyone will come upon is the main room. A large, U-shape room with shelving covered with items of all kinds, souvenirs and treasures from the travels that the head of the Kitsune family has been on through the Gate. A small lectern holding many books, with an inkwell and brush atop it, is where the Kitsune head will write down their experiences, and their learnings, from the realms they’ve been to.

There are countless books that sit under the shelving right beside the lectern that are filled with notes taken by prior heads of the Kitsune family. However, the shelves will only hold the items brought to it by the current head. Those that belonged to the ones who have passed on, are buried with them, to keep from cluttering the room too much, and clear it for the next in line.

Seen below are the two sides of this central room, which lead to the two bedrooms of the home on each side, with windows that look out to the Tori Gate itself.

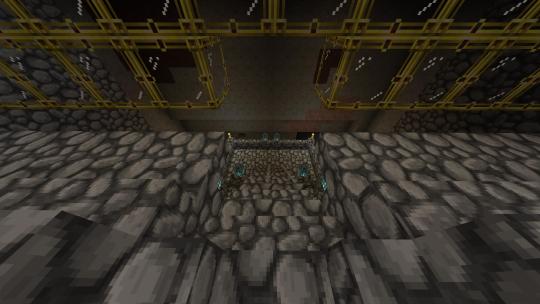

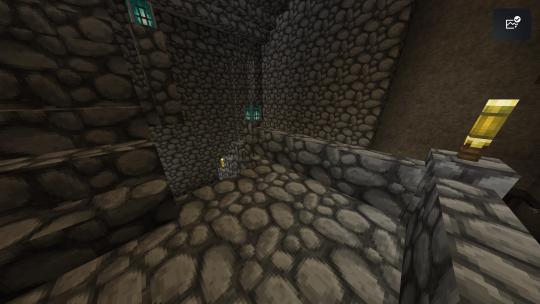

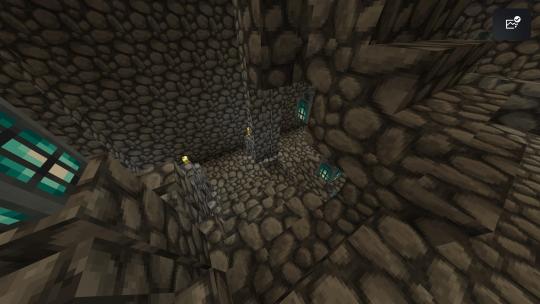

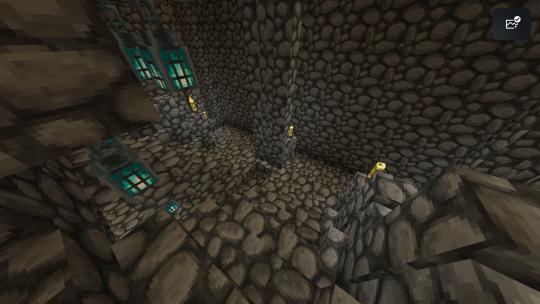

Between the Home, and the Shrine up the hill, there’s a small area that leads down beneath the land itself, into a cavernous area. This is area is one that came to mind while I was trying to create a representation of the Shrine within the game, and the idea around it is still fairly new, but I’m considering this now a canon thing.

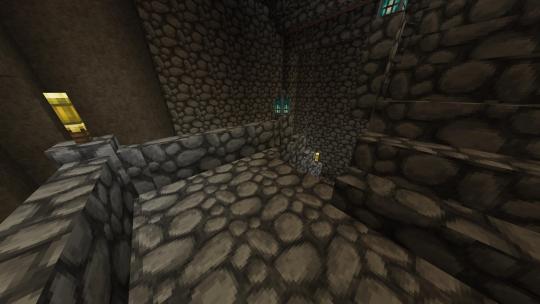

Past this small opening is a large staircase which descends into the earth, traveling down into an open cavern where, eventually, one may find the grave of the Ancient Kitsune, and those of the deceased descendants around her. Visitors aren’t allowed to traverse this area, and any action to do so will be seen as hostility, unless they are accompanied by a Kitsune from the family.

I’ve yet to really flesh out this underground area in the game, I’m going to use it as a sort of storage and base for storing resources, doing crafting and such, and expanding it out into the various different automated farms for things like food and other materials. As well as a place to descend from, leading down to a mining area to get resources from deep underground through.

Essentially, this form of descent seen in the images is continued on deep into the earth beneath, and at the very bottom lies the grave of the Ancient Kitsune. Her descendants are buried around her, within the walls, going up one level per generation.

#The Kitsune {Kyuushi}#a rough visual of the Shrine the Tori and the Home#Truths Among Myths {Headcanons}

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Day 144 – Singapore to Kuala Lumpur

My final day in Singapore was packed with life-admin, complete with many visa arrangements, accommodation, ferry and flight bookings for the rest of my time in South East Asia. I bounced around the little shops in Chinatown, picking up everything from a replacement tripod and medications, to Tiger Balm for my still-recovering knee. I figured this was a good time to stock up on the essentials before I began hostel hopping through Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam over the following 7 weeks. After a final hawker centre meal, I packed up my bag and headed back to Changi Airport, boarding a 7:30pm Air Asia Flight to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

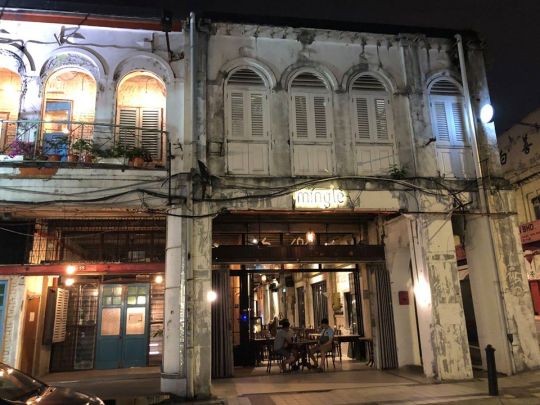

After a short, 1-hour flight North, I arrived in KL in the early evening, easily passing through customs and boarding the metro from KL Sentral to Pasar Seni. Arriving in Chinatown after dark, I headed to my nearby hostel, Mingle, which had come highly recommend to me from a fellow traveller I had met in Morocco. The air in Kuala Lumpur was thick with humidity, and I was immediately drenched with sweat after only a few minutes of walking. Even after dark, the pre-war architecture of Chinatown was fascinating. Multi storied shophouses were on every corner - some tastefully restored and painted, some weather-beaten and water stained. Large flickering billboards hung over the streets. It also felt like a neighbourhood that never sleeps! Restaurant and bar customers spilled out into the streets, sitting on bright plastic stools and eating at low tables set up on the sidewalks. My hostel for the next 3 nights, Mingle, was in a historic building, the white walls streaked with black stains, having weathered years of colonial rule and World War 2. Inside, the hostel itself had been tastefully refurbished, while also keeping many of the historic touches from the century-old original construction. I immediately crashed for the night on arrival, gearing up for a busy few days of travelling around the lively capital of Malaysia.

Mingle Hostel in Chinatown

Day 145 – Kuala Lumpur and Batu Caves

Enjoying breakfast on the rooftop terrace of my hostel, I met Jannes, a German traveller who had also recently arrived in KL. Since we were both planning on heading to the Batu Caves that day, we joined forces, hailing a Grab (Asia’s counterpart to Uber) and setting out to our destination, 30 minutes north of the city. It was fascinating to get a sense of the scale of Kuala Lumpur as we drove – the greater city area - called the Klang Valley - is home to over 7.5 million people, and is one of the fastest growing metropolitan areas in Southeast Asia, both in population and economic power. The Malaysian capital is also known for its multicultural population, made up primarily of Malay, Indian and Chinese residents – resulting in a fusion of cultures and religions, vibrant events and festivities, and incredible local cuisine.

Streets of Kuala Lumpur

The morning sun was already furiously beating down as we arrived at the Batu Caves, located in a large limestone hill. This 100-year-old Hindu temple is an important religious landmark, with three massive, naturally formed limestone caves which have been turned into shrines. As we approached the entry gate and took in the massive limestone hill, I caught sight of the colossal, gold statue of the Hindu deity Murugan, towering 140 feet high in front of the staircase leading to the caves. Passing underneath the statue, we began to ascend the 272 steps towards the grottoes. Hundreds of curious macaque monkeys scampered around the limestone cliffs and darted along the stairs next to us. We kept our belongings close to us – as these monkeys are notorious pickpockets!

Macaque Monkeys

Arriving at the top of the stairs, we entered the gigantic, limestone cavern, with craggy rock formations hanging from the vaulted ceiling, and smaller crevices and caverns leading away from the main “Cathedral Cave”. We spent the next hour wandering through the enormous caves, scattered with numerous Hindu shrines, dedicated to different deities. Swirling plumes of incense followed us as we wandered along. The towering limestone ceilings had a few large holes, letting in the sun and illuminating the caves in a mesmerizing way. The caves were a truly impressive sight.

Batu Caves

Jannes and I hailed another Grab for a ride back into the city, ready to tuck into to a delicious Malaysian lunch. We were directed to the nearby Old China Café – a cosy Peranakan café serving delicious Chinese Malay dishes such as Char Kuey Teow (flat noodle stir-fry), Lemak Nenas (pineapple prawn curry), Teh Tarik (a hot milk tea prepared with condensed milk), blue coconut rice, and Nasi Lemak (a dish cooked in a pandan leaf with coconut milk). My first venture into Malaysian cuisine certainly did not disappoint – with Malaysia ultimately ending up being my favourite country for food throughout all of my travels!

Returning to our hostel, we met up with other travellers Jannes had previously befriended– Bart from Brussels, Caroline from London, and Egle, a true citizen of the world, who had lived across Europe, Shanghai, and was in the process of moving to Byron Bay to study yoga. In the afternoon, Jannes, Bart and I set out to explore Chinatown. We first visited Sri Mahamariamman Temple, the oldest Hindu temple in Kuala Lumpur. A ornate, 5-tiered Gopuram tower rose above the entrance, sculpted with colourful depictions of numerous Hindu deities. Taking off our shoes, we wandered the edge of the main prayer hall, quietly taking in the relaxed atmosphere and colourful murals while trying not to disturb the worshippers.

We continued onwards to Petaling Street Market. Formerly the location of a tapioca mill, modern-day Petaling street is a flea market, chock-a-block with shops, food stalls, selling everything under the sun – fake branded items, Malaysian cuisine, fishmongers, souvenirs, and local goods. At night, the whole area transforms into a vibrant night market, with vendors selling countless discount items for only a few Ringgits. Heading a few blocks over, we walked through Central Market, also known as Pasar Seni, which is a handicrafts market, and the former location of a wet market. We spend some time poking around the different stores, with items such as batik prints, paintings and Chinese herbs, to palmistry booths and pearl vendors from Malaysian Borneo.

Sultan Abdul Samad Building

Leaving the markets behind, we walked along the banks of the Klang and Gombak rivers, taking in the spectacular architecture along our way – in particular the Sultan Abdul Samad Building, a 1800s heritage building which originally housed the offices of the British colonial administration prior to Malaysia’s independence in 1957. The long building hosts several impressive architectural features, from onion-shaped copper domes and dozens of pink and white bricked archways, to spiral staircases and a central clock-tower designed to echo London’s Big Ben.

At the confluence of the two rivers sits the Masjid Jamek of Kuala Lumpur, a century-old mosque. Built with red brick and marble, the striking designs of the mosque incorporates Moorish and north Indian Islamic architecture.

Masjid Jamek of Kuala Lumpur

As we continued along the river, we became gradually more fatigued from the overpowering heat, finally stopping for a cold Angkor beer on a covered patio. Relaxing in the shade, we recharged our batteries before heading back to our hostel, meeting up with Caroline. Our group headed out for dinner in Chinatown, sitting on tiny red stools along the sidewalk and sharing Malaysian dishes, including Hokkien Fried Noodles, Beef Char Kuey Teow, and even trying a Fried Frog and Ginger dish! For my second meal out – I continued to be blown away by how good Malaysian food was.

As night fell, we haggled with a taxi and caught a ride to Kuala Lumpur’s City Centre, (or “KLCC”), the modern epicentre of the city, complete with futuristic skyscrapers, office towers, upscale shopping centres, luxury hotels and dining. The most famous landmarks in the centre of KLCC are the Petronas Twin Towers, 88-storey buildings with a bridge joining the towers at the 41st and 42nd floors. At night, the towers are lit up, giving them a dazzling, spaceship-like aura.

Petronas Towers

We walked to KLCC park, a 50-acre garden with man-made lakes and fountains, located directly across from the twin towers. We were just on time to catch the final musical fountain show, where fountain displays are choreographed to music and lights, set against KLCC’s impressive skyline.

Capping off a busy day in Kuala Lumpur, our group of four headed back to Chinatown, where we set up camp at our hostel’s rooftop cocktail bar, swapping stories late into the night.

Day 146 – Kuala Lumpur

Given the overpowering heat from the day before, Caroline, Bart and I decided to go on the hunt for a rooftop pool for a day of R&R. We were lucky that Mingle had a sister hostel – Sky Society, and our host was able to get us passes to the rooftop pool on the 37th floor for free. Not quite knowing what to expect, we jumped in a Grab and headed out of Chinatown to the neighbourhood of Putra, packing a lunch, towels and drinks for the day. After going through many layers of security, (where we were certain we would be turned away!), we finally made it to the rooftop infinity pool. Considering we hadn’t paid for anything aside from our transit, I was stunned by the city view along the horizon. We had a perfect view of the Petronas Twin Towers, The Menara Tower, and the distant hills beyond the city limits. We jokingly told ourselves that we had found the backpackers’ answer to Marina Bay Sands! We spent the remainder of the afternoon soaking up the sun and plunging in the pool to cool off, all while admiring KL’s impressive skyline.

In the late afternoon, we boarded a train back to Chinatown, showering and changing before heading out for another streetside dinner of delicious Malaysian food. As the evening fell, we caught a Grab to Heli Lounge Bar, located next to the Menara Tower. Heli Lounge Bar is essentially a fully functional helicopter pad by day, which at night converts into the coolest rooftop bar I have ever seen. Unbelievably, there was nothing by retractable rope separating us from the edge of the helipad, and we had unobstructed, 360-degree views of the surrounding cityscape. We found lounge chairs on the edge of the helipad, and enjoyed several aviation-themed cocktails, watching the daylight fade over Kuala Lumpur. As night fell, a sea of twinkling lights stretched as far as my eye could see. It was truly a night I will never forget.

0 notes

Text

Opinion: An ancient land, newly optimistic

The downtown has an energy that is a long way from the sleepy Soviet city I first visited in the 1980s.

Each time I’ve come to Yerevan in the past decade, the city has surprised me with its evolving elegance and cultural richness.

The downtown has an energy that is a long way from the sleepy Soviet city I first visited in the 1980s. Walking the shady avenues off Republic Square on a recent visit, I found the city has become a hip place, with wine bars, microbreweries, cafes, art galleries, boutiques selling crafts and carpets, and an ever-new array of restaurants, as well as upscale hotels and clothing stores.

The new mood is defined by the millennial generation’s role in the velvet revolution of this past spring. After weeks of peaceful protests, the civil society has pushed from power an old regime that much of the nation viewed as dysfunctional and corrupt, representing a continuation of old Soviet mentalities. When Nikol Pashinyan, a prominent journalist, activist and former parliamentarian became prime minister May 8, a sense of a new era enveloped the country.

In June, I sat in a vine-trellised courtyard restaurant and art gallery on Abovian Street with Armen Ohanyan, a young fiction writer, and Arevik Ashakharoyan, a literary agent. I was hearing Armenia’s new voices of optimism. “Soviet minds are a thing of the past,” Ohanyan said.

“The new generation, born after the fall of the Soviet Union, is playing a big role in the new democracy,” Ashakharoyan said. “We are tech-savvy and have no ties to the corrupt Soviet past.”

Ohanyan added: “We feel a new future. The reign of oligarchs is over.”

Having written about Armenia for decades, their words resonated. I am a poet and nonfiction writer of Armenian ancestry and have been to Armenia five times in the past decade. My trips are often connected to my work — a translation of one of my books, a lecture tour, a symposium.

I started the day grazing on a classic Armenian breakfast spread at the Armenia Marriott Hotel Yerevan, an elegant hotel on Republic Square with fine local cuisine: bastermas (spicy, cured beef); paper-thin or thicker warm lavash; local cheeses; jams with strawberries or apricots or walnuts; thick yogurt; cherries, apricots, blackberries and melons from local orchards; fruit nectars and orange, red and brown rolls of thick grape molasses stuffed with walnuts (sujuk); and black tea from a samovar. The presentation was beautiful, and the Caucasian sun poured through the windows.

Like its cuisine, the country has a long, rich history. Armenia, which became an independent republic in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union, is a small, landlocked nation in the southwest Caucasus, at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. The country today is what remains of a once-ancient empire that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Caspian Sea in the first century B.C., before it was conquered by the Romans. It was the first nation to make Christianity its state religion, in 301.

Conquered by Byzantines, Persians, Mongols and Seljuks, then colonized by the Ottoman Turks in the 16th century, Armenians were subject to large-scale massacres in the 19th century, during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and were the victims of what genocide scholars regard as one of the first genocides of the modern era, by the Ottoman Turkish government in 1915. (Turkey denies that the killings were genocide.)

Armenia became a Soviet Republic in 1920, endured Stalin’s purges and repression, a massive earthquake in 1988 and a war with neighboring Azerbaijan in the 1990s that has flared up again in recent years over the province of Nagorno-Karabakh. By all rational odds, Armenia should not be on the map today.

Having survived such a harsh history, Armenia has emerged as a democracy that cherishes the many layers of its past. Today, the capital, Yerevan — which dates to the seventh century B.C. and was founded on the walls of the Urartian city of Erebuni — is a blend of ancient culture, artisan tradition, modern architecture and high-tech, postmodern style, exemplified by the new condominiums and high-end shops on the pedestrian Northern Boulevard.

On Sept. 29-30, Yerevan will celebrate its 2,800th anniversary, making it one of the oldest cities in the world. In the ruins of the ancient fortress on Erebuni Fortress Hill, fragments of murals with images of sacred animals evoke the late Bronze Age. The Erebuni museum has a fine collection of artifacts, including a huge wine storage container that documents Armenia’s winemaking tradition from the Bronze Age.

Those amphoras prompted me to visit the Ararat Brandy Factory, an imperial monument to the Armenian passion for the grape, set on a perch overlooking Victory Bridge, which spans the Hrazdan River. I love walking the beautifully lit cavernous halls filled with Caucasian oak barrels. Ararat Brandy has been a major export for more than a century, and its velvety depths were made legendary by Winston Churchill, who drank it daily for decades. I left with a glow of delight after the brandy tasting that concludes the tour.

Yerevan is a city where many avenues are named after Armenia’s great figures: the early 20th-century poet Yeghishe Charents, the fifth-century historian Movses Koranatsi, the 19th-century novelist Katchadour Abovian, the composer Komitas (1869-1935), to name a few. It’s a city of great museums, including the Matenadaran, which has a rich collection of medieval illuminated manuscripts and books in Armenian, the National Gallery and the History Museum of Armenia.

I always head first for the intimate museums dedicated to major figures. The Saryan museum, for example, has two floors of works by the avant-garde landscape and modernist painter Martiros Saryan (1880-1972). In a stately stone house, the Sergei Parajanov Museum is a celebration of the great 20th-century filmmaker and visual artist’s work: mixed media collages, paintings, conceptual installations and miniature drawings on matchbooks and bottle caps from the time he was imprisoned by the Soviet authorities for “decadent” art and homosexuality.

I always get a good workout climbing the 572 steps of the Cafesjian Center for the Arts (also known as Cascade). It’s a dramatic complex rising up from the tree-shaded, cafe-abundant Tumayan Street in five monumental limestone tiers of fountains, topiary gardens and sculptures. If you tire of the climb, you can slip inside and take the escalator, and soak up one of the most important collections of modern glass in the world, as well as paintings, drawings and sculpture.

No one should come to Yerevan without visiting the extraordinary Armenian Genocide Museum and Memorial, also known as the Tsitsernakaberd (meaning swallow’s fortress) Memorial Complex. It is situated on a hill that overlooks the city and Mount Ararat, Armenia’s national symbol, just across the border in Turkey.

Built of sleek gray basalt, its elegant new wing was designed by the museum’s director, Hayk Demoyan, and his wife, designer Lucine Matevosian. The wide circular exhibit halls wind from a top floor down to a second floor. Photos, maps and documentary footage on various screens accompany text that explores the history of the horrific events that took the lives of more than 1 million Armenians in 1915. From the museum visitors walk the stone walkway to the memorial — towering twin obelisks (a symbol of eternity) and 12 20-foot high stone pillars — to lean over a large circular area where an eternal flame burns and sacred music plays.

Back in Yerevan for the evening, I dined with friends and found the cuisine more inventive than ever. Restaurants blend the traditions of the Armenian Caucasus with the Middle East as refugees from Syria and Iraq make their impact. At Sherep, one of the hottest new places, with a chic open kitchen and late-night jazz, I had mountain sorrel soup; tender stuffed grape leaves; eggplant sautéed in olive oil and rolled up with minced walnuts, dill, garlic and yogurt; and succulent lamb chops. At Vostan, in an old Russian-period stone building on Abovian Street, I feasted on pink, succulent, wood-grilled Lake Sevan trout.

My travels frequently take me beyond Yerevan. Wherever you go in Armenia, you are journeying through an open-air museum where churches and monasteries, even a Hellenic temple, are built into the cliffs or perched at the edges of canyons or green gorges, with searing vistas framed by the ever-blue sky. Thousand-year-old lacelike carved stone crosses (khatchgars) emerge from fields of roadside poppies.

Because Armenia is defined by mountains, canyons, gorges, forests, rushing streams and rivers, lakes, grassy highlands and dales, it has become a prime destination for hikers. The new Transcaucasian Trail runs from Georgia through Armenia into Azerbaijan, and offers extraordinary trails from the Dilijan National Park in the northern mountains to the caves of Goris in the south. Many trails intersect with ancient monasteries and churches.

For a small country Armenia has an amazing diversity of flora and fauna; about 240 bird species breed in Armenia and nearly 400 move through the country, making Armenia a birder’s paradise.

On a sunny morning, I headed east from Yerevan in a minivan with my superb guide, Katar Taslakyan, and a driver, Raphael Hovakimyan, whose musical selections — jazz and R&B — filled the van. About 40 minutes later, we stopped at Charents Arch, an impressive monument to Armenia’s great modern poet Yeghishe Charents (1897-1937). From there, we got a stunning view of the glistening, grassy highlands and snow-capped Mount Ararat.

In another 15 minutes, we were at Garni, a beautifully proportioned Greco-Roman temple believed to have been built by King Tiridates I to the sun god Mihr. The vistas from Garni, which is perched at the lip of a gorge, are spectacular.

We drove on until the conical dome of Geghardavank (the Monastery of the Spear) emerges from behind a stone wall. A UNESCO World Heritage site (like many monasteries in Armenia), the medieval church was built partly out of the side of a mountain. Monks’ caves adorned with stone crosses and arches dot the cliff face. I walked into a chapel and stared at the animal carvings on the wall as light fell through the round opening in the dome, a feature in Armenian medieval churches that creates a mysterious dark light and a heightened sense of the cosmic. A stream from the mountain runs through a wall, and pilgrims and tourists pass their hands through it.

At Geghard, as with most Armenian medieval churches, you enter a distinctive organic architecture, in which building and carvings flow with the contours of nature. Unlike the Gothic cathedrals of Europe, these churches are smaller in scale and designed as intimate spaces. Here, you feel the stones are speaking to you, the light grazes you.

The next day, we drove south from Yerevan into the fertile Ararat Valley. In June, the apricot orchards are popping with Armenia’s bright yellow national fruit and the vineyards are green. On this clear morning, Mount Ararat rose from a bank of clouds and the hot sun was mitigated by cool breezes.

Farther south, in Vayots Dzor province, our van climbed the road to Noravank, a complex that includes two medieval churches, one of which was designed by the architect and artist Momik. Again, I’m blown away as monks’ caves appear in jagged red cliffs that remind me of Arizona, and the milky tan limestone of the Myrig Adzvadzeen church glistens in the sunlight against a brilliant blue sky and rising mountains. The chapel at Noravank is luminous with light pouring through the windows. Gazing out those windows to green hillsides, red cliffs, blue sky, I felt the shimmer of the sublime.

Four miles from Noravank, I went from spiritual to chthonic, as I walked up the steps of a craggy cliff to the Areni cave where, in 2007, the earliest known clay amphoras (karases) — some 6,100 years old — were discovered. Armenia is considered the birthplace of winemaking. Archaeologists are still working there, and the Copper Age karases are well displayed in the cave where they were once used.

Winemaking runs deep in the Armenian vein, and the famous Areni grape with its thick skin is the source of some of the best new wines anywhere. Throughout my visit, I had various full-bodied reds that were smooth and dry, with complex flavors enhanced by Caucasian oak barrels, reminding me of some fine pinot noirs of Oregon and certain red Burgundies. Among the better-known labels are Areni, Kadar, Kara, Trinity and Zorah.

After a night on the Goris River at Mirhav, a beautifully appointed inn with antique Armenian artifacts and rugs, we drove to 11,000 feet through a fantasia of chirping nightingales, swooping eagles and clouds lifting off the green valley to the world’s longest nonstop, reversible tramway to reach Tatev, a ninth-century monastery. As a Baroque concerto spilled through the tramway’s speakers, our glass car floated above villages and ancient churches, by cliffs and grassy mountains and past gliding hawks toward the monastery, with its two conical domed churches perched at the cliff’s edge.

Heading north past potato fields and farmlands, meadows of poppies and royal blue delphiniums, we drove up the western shore of Lake Sevan, one of the largest high-altitude lakes in Eurasia. Its turquoise water is a resort for bathers and fishermen, and an important source for fishing, irrigation and hydroelectric power. At a lakeside restaurant called Dzovadzots, I had a perfect whitefish soup.

A half-hour north, the ninth-century Sevanavank monastery, with its two small beautiful, earth-colored churches on a peninsula, is worth the climb up the steps from the shore below.

Just north of Lake Sevan, we crossed into the alpine mountain region of Tavush where streams and hiking trails wind through the lush forests of Dilijan National Park. The stunning monastery of Haghartsin is nestled on a forested mountain.

The spa town of Dilijan, situated in the park, is an atmospheric place out of a Chekhov story. Its chalet-style buildings with gable-tiled roofs, open-air theater and mountain views made it a popular vacation spot for wealthy Russians in the 19th century; today it is a retreat for artists. One of the creative entrepreneur and philanthropist James Tufenkian’s four unique hotels is housed in a complex of restored 19th-century houses.

From there, we drove to Avan Zoraget, another Tufenkian hotel, beneath the mountains on the Debed River. Sleek, imaginative and appointed with Tufenkian carpets, its rooms have lovely views. The restaurant overlooking the river offers a sumptuous repertoire: sautéed local greens and onions with yogurt; smoky eggplant dip blended with tahini; spelt with wild mushrooms; a tongue-melting sou boreg (thin flat noodles layered with Armenian cheeses), chicken cooked with dried plum and pomegranate sauce; and superb dry white wine.

Back in Yerevan the next evening, I walked through an arch onto an old cobblestone street off bustling Amirian Street and found Anteb, a Syrian-Armenian restaurant, where we had spicy, crepe-thin lahmajuns (Armenian pizza); a piquant muhamara (walnut, pomegranate molasses and red pepper dip) that you scoop up with hot, puffy lavash; and kuftas, crisp shells of cracked wheat bursting with lamb and herbs. The next night my friend Ashot took me to Babylon, an Arabic-Iraqi restaurant where our feast included crispy boregs (phyllo dough wrapped around cheese), meatless stuffed grape leaves and the most tender lamb kebabs I’ve had outside my mother’s kitchen.

I never leave Yerevan without meandering through the Vernissage, the open-air market in a park along Aram and Buzant streets where there are stalls and stalls of ceramics, folk and contemporary art, rugs, textiles, jewelry and more. I bought two small antique Caucasian kilims before I wandered back to Republic Square, where I end most evenings.

At night the square, with its monumental rosy tufa stone buildings, is lit up; the fountains spew through colored lights, music plays, people dance. It’s a nightly ritual in Yerevan in the warm-weather months — a down-home celebration to end a day, and a resilient response to the harsh history of this new nation that has emerged from an ancient civilization.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Peter Balakian © 2018 The New York Times

source http://www.newssplashy.com/2018/08/opinion-ancient-land-newly-optimistic_22.html

0 notes

Link

The downtown has an energy that is a long way from the sleepy Soviet city I first visited in the 1980s.

Each time I’ve come to Yerevan in the past decade, the city has surprised me with its evolving elegance and cultural richness.

The downtown has an energy that is a long way from the sleepy Soviet city I first visited in the 1980s. Walking the shady avenues off Republic Square on a recent visit, I found the city has become a hip place, with wine bars, microbreweries, cafes, art galleries, boutiques selling crafts and carpets, and an ever-new array of restaurants, as well as upscale hotels and clothing stores.

The new mood is defined by the millennial generation’s role in the velvet revolution of this past spring. After weeks of peaceful protests, the civil society has pushed from power an old regime that much of the nation viewed as dysfunctional and corrupt, representing a continuation of old Soviet mentalities. When Nikol Pashinyan, a prominent journalist, activist and former parliamentarian became prime minister May 8, a sense of a new era enveloped the country.

In June, I sat in a vine-trellised courtyard restaurant and art gallery on Abovian Street with Armen Ohanyan, a young fiction writer, and Arevik Ashakharoyan, a literary agent. I was hearing Armenia’s new voices of optimism. “Soviet minds are a thing of the past,” Ohanyan said.

“The new generation, born after the fall of the Soviet Union, is playing a big role in the new democracy,” Ashakharoyan said. “We are tech-savvy and have no ties to the corrupt Soviet past.”

Ohanyan added: “We feel a new future. The reign of oligarchs is over.”

Having written about Armenia for decades, their words resonated. I am a poet and nonfiction writer of Armenian ancestry and have been to Armenia five times in the past decade. My trips are often connected to my work — a translation of one of my books, a lecture tour, a symposium.

I started the day grazing on a classic Armenian breakfast spread at the Armenia Marriott Hotel Yerevan, an elegant hotel on Republic Square with fine local cuisine: bastermas (spicy, cured beef); paper-thin or thicker warm lavash; local cheeses; jams with strawberries or apricots or walnuts; thick yogurt; cherries, apricots, blackberries and melons from local orchards; fruit nectars and orange, red and brown rolls of thick grape molasses stuffed with walnuts (sujuk); and black tea from a samovar. The presentation was beautiful, and the Caucasian sun poured through the windows.

Like its cuisine, the country has a long, rich history. Armenia, which became an independent republic in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union, is a small, landlocked nation in the southwest Caucasus, at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. The country today is what remains of a once-ancient empire that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Caspian Sea in the first century B.C., before it was conquered by the Romans. It was the first nation to make Christianity its state religion, in 301.

Conquered by Byzantines, Persians, Mongols and Seljuks, then colonized by the Ottoman Turks in the 16th century, Armenians were subject to large-scale massacres in the 19th century, during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and were the victims of what genocide scholars regard as one of the first genocides of the modern era, by the Ottoman Turkish government in 1915. (Turkey denies that the killings were genocide.)

Armenia became a Soviet Republic in 1920, endured Stalin’s purges and repression, a massive earthquake in 1988 and a war with neighboring Azerbaijan in the 1990s that has flared up again in recent years over the province of Nagorno-Karabakh. By all rational odds, Armenia should not be on the map today.

Having survived such a harsh history, Armenia has emerged as a democracy that cherishes the many layers of its past. Today, the capital, Yerevan — which dates to the seventh century B.C. and was founded on the walls of the Urartian city of Erebuni — is a blend of ancient culture, artisan tradition, modern architecture and high-tech, postmodern style, exemplified by the new condominiums and high-end shops on the pedestrian Northern Boulevard.

On Sept. 29-30, Yerevan will celebrate its 2,800th anniversary, making it one of the oldest cities in the world. In the ruins of the ancient fortress on Erebuni Fortress Hill, fragments of murals with images of sacred animals evoke the late Bronze Age. The Erebuni museum has a fine collection of artifacts, including a huge wine storage container that documents Armenia’s winemaking tradition from the Bronze Age.

Those amphoras prompted me to visit the Ararat Brandy Factory, an imperial monument to the Armenian passion for the grape, set on a perch overlooking Victory Bridge, which spans the Hrazdan River. I love walking the beautifully lit cavernous halls filled with Caucasian oak barrels. Ararat Brandy has been a major export for more than a century, and its velvety depths were made legendary by Winston Churchill, who drank it daily for decades. I left with a glow of delight after the brandy tasting that concludes the tour.

Yerevan is a city where many avenues are named after Armenia’s great figures: the early 20th-century poet Yeghishe Charents, the fifth-century historian Movses Koranatsi, the 19th-century novelist Katchadour Abovian, the composer Komitas (1869-1935), to name a few. It’s a city of great museums, including the Matenadaran, which has a rich collection of medieval illuminated manuscripts and books in Armenian, the National Gallery and the History Museum of Armenia.

I always head first for the intimate museums dedicated to major figures. The Saryan museum, for example, has two floors of works by the avant-garde landscape and modernist painter Martiros Saryan (1880-1972). In a stately stone house, the Sergei Parajanov Museum is a celebration of the great 20th-century filmmaker and visual artist’s work: mixed media collages, paintings, conceptual installations and miniature drawings on matchbooks and bottle caps from the time he was imprisoned by the Soviet authorities for “decadent” art and homosexuality.

I always get a good workout climbing the 572 steps of the Cafesjian Center for the Arts (also known as Cascade). It’s a dramatic complex rising up from the tree-shaded, cafe-abundant Tumayan Street in five monumental limestone tiers of fountains, topiary gardens and sculptures. If you tire of the climb, you can slip inside and take the escalator, and soak up one of the most important collections of modern glass in the world, as well as paintings, drawings and sculpture.

No one should come to Yerevan without visiting the extraordinary Armenian Genocide Museum and Memorial, also known as the Tsitsernakaberd (meaning swallow’s fortress) Memorial Complex. It is situated on a hill that overlooks the city and Mount Ararat, Armenia’s national symbol, just across the border in Turkey.

Built of sleek gray basalt, its elegant new wing was designed by the museum’s director, Hayk Demoyan, and his wife, designer Lucine Matevosian. The wide circular exhibit halls wind from a top floor down to a second floor. Photos, maps and documentary footage on various screens accompany text that explores the history of the horrific events that took the lives of more than 1 million Armenians in 1915. From the museum visitors walk the stone walkway to the memorial — towering twin obelisks (a symbol of eternity) and 12 20-foot high stone pillars — to lean over a large circular area where an eternal flame burns and sacred music plays.

Back in Yerevan for the evening, I dined with friends and found the cuisine more inventive than ever. Restaurants blend the traditions of the Armenian Caucasus with the Middle East as refugees from Syria and Iraq make their impact. At Sherep, one of the hottest new places, with a chic open kitchen and late-night jazz, I had mountain sorrel soup; tender stuffed grape leaves; eggplant sautéed in olive oil and rolled up with minced walnuts, dill, garlic and yogurt; and succulent lamb chops. At Vostan, in an old Russian-period stone building on Abovian Street, I feasted on pink, succulent, wood-grilled Lake Sevan trout.

My travels frequently take me beyond Yerevan. Wherever you go in Armenia, you are journeying through an open-air museum where churches and monasteries, even a Hellenic temple, are built into the cliffs or perched at the edges of canyons or green gorges, with searing vistas framed by the ever-blue sky. Thousand-year-old lacelike carved stone crosses (khatchgars) emerge from fields of roadside poppies.

Because Armenia is defined by mountains, canyons, gorges, forests, rushing streams and rivers, lakes, grassy highlands and dales, it has become a prime destination for hikers. The new Transcaucasian Trail runs from Georgia through Armenia into Azerbaijan, and offers extraordinary trails from the Dilijan National Park in the northern mountains to the caves of Goris in the south. Many trails intersect with ancient monasteries and churches.

For a small country Armenia has an amazing diversity of flora and fauna; about 240 bird species breed in Armenia and nearly 400 move through the country, making Armenia a birder’s paradise.

On a sunny morning, I headed east from Yerevan in a minivan with my superb guide, Katar Taslakyan, and a driver, Raphael Hovakimyan, whose musical selections — jazz and R&B — filled the van. About 40 minutes later, we stopped at Charents Arch, an impressive monument to Armenia’s great modern poet Yeghishe Charents (1897-1937). From there, we got a stunning view of the glistening, grassy highlands and snow-capped Mount Ararat.

In another 15 minutes, we were at Garni, a beautifully proportioned Greco-Roman temple believed to have been built by King Tiridates I to the sun god Mihr. The vistas from Garni, which is perched at the lip of a gorge, are spectacular.

We drove on until the conical dome of Geghardavank (the Monastery of the Spear) emerges from behind a stone wall. A UNESCO World Heritage site (like many monasteries in Armenia), the medieval church was built partly out of the side of a mountain. Monks’ caves adorned with stone crosses and arches dot the cliff face. I walked into a chapel and stared at the animal carvings on the wall as light fell through the round opening in the dome, a feature in Armenian medieval churches that creates a mysterious dark light and a heightened sense of the cosmic. A stream from the mountain runs through a wall, and pilgrims and tourists pass their hands through it.

At Geghard, as with most Armenian medieval churches, you enter a distinctive organic architecture, in which building and carvings flow with the contours of nature. Unlike the Gothic cathedrals of Europe, these churches are smaller in scale and designed as intimate spaces. Here, you feel the stones are speaking to you, the light grazes you.

The next day, we drove south from Yerevan into the fertile Ararat Valley. In June, the apricot orchards are popping with Armenia’s bright yellow national fruit and the vineyards are green. On this clear morning, Mount Ararat rose from a bank of clouds and the hot sun was mitigated by cool breezes.

Farther south, in Vayots Dzor province, our van climbed the road to Noravank, a complex that includes two medieval churches, one of which was designed by the architect and artist Momik. Again, I’m blown away as monks’ caves appear in jagged red cliffs that remind me of Arizona, and the milky tan limestone of the Myrig Adzvadzeen church glistens in the sunlight against a brilliant blue sky and rising mountains. The chapel at Noravank is luminous with light pouring through the windows. Gazing out those windows to green hillsides, red cliffs, blue sky, I felt the shimmer of the sublime.

Four miles from Noravank, I went from spiritual to chthonic, as I walked up the steps of a craggy cliff to the Areni cave where, in 2007, the earliest known clay amphoras (karases) — some 6,100 years old — were discovered. Armenia is considered the birthplace of winemaking. Archaeologists are still working there, and the Copper Age karases are well displayed in the cave where they were once used.

Winemaking runs deep in the Armenian vein, and the famous Areni grape with its thick skin is the source of some of the best new wines anywhere. Throughout my visit, I had various full-bodied reds that were smooth and dry, with complex flavors enhanced by Caucasian oak barrels, reminding me of some fine pinot noirs of Oregon and certain red Burgundies. Among the better-known labels are Areni, Kadar, Kara, Trinity and Zorah.

After a night on the Goris River at Mirhav, a beautifully appointed inn with antique Armenian artifacts and rugs, we drove to 11,000 feet through a fantasia of chirping nightingales, swooping eagles and clouds lifting off the green valley to the world’s longest nonstop, reversible tramway to reach Tatev, a ninth-century monastery. As a Baroque concerto spilled through the tramway’s speakers, our glass car floated above villages and ancient churches, by cliffs and grassy mountains and past gliding hawks toward the monastery, with its two conical domed churches perched at the cliff’s edge.

Heading north past potato fields and farmlands, meadows of poppies and royal blue delphiniums, we drove up the western shore of Lake Sevan, one of the largest high-altitude lakes in Eurasia. Its turquoise water is a resort for bathers and fishermen, and an important source for fishing, irrigation and hydroelectric power. At a lakeside restaurant called Dzovadzots, I had a perfect whitefish soup.

A half-hour north, the ninth-century Sevanavank monastery, with its two small beautiful, earth-colored churches on a peninsula, is worth the climb up the steps from the shore below.

Just north of Lake Sevan, we crossed into the alpine mountain region of Tavush where streams and hiking trails wind through the lush forests of Dilijan National Park. The stunning monastery of Haghartsin is nestled on a forested mountain.

The spa town of Dilijan, situated in the park, is an atmospheric place out of a Chekhov story. Its chalet-style buildings with gable-tiled roofs, open-air theater and mountain views made it a popular vacation spot for wealthy Russians in the 19th century; today it is a retreat for artists. One of the creative entrepreneur and philanthropist James Tufenkian’s four unique hotels is housed in a complex of restored 19th-century houses.

From there, we drove to Avan Zoraget, another Tufenkian hotel, beneath the mountains on the Debed River. Sleek, imaginative and appointed with Tufenkian carpets, its rooms have lovely views. The restaurant overlooking the river offers a sumptuous repertoire: sautéed local greens and onions with yogurt; smoky eggplant dip blended with tahini; spelt with wild mushrooms; a tongue-melting sou boreg (thin flat noodles layered with Armenian cheeses), chicken cooked with dried plum and pomegranate sauce; and superb dry white wine.

Back in Yerevan the next evening, I walked through an arch onto an old cobblestone street off bustling Amirian Street and found Anteb, a Syrian-Armenian restaurant, where we had spicy, crepe-thin lahmajuns (Armenian pizza); a piquant muhamara (walnut, pomegranate molasses and red pepper dip) that you scoop up with hot, puffy lavash; and kuftas, crisp shells of cracked wheat bursting with lamb and herbs. The next night my friend Ashot took me to Babylon, an Arabic-Iraqi restaurant where our feast included crispy boregs (phyllo dough wrapped around cheese), meatless stuffed grape leaves and the most tender lamb kebabs I’ve had outside my mother’s kitchen.

I never leave Yerevan without meandering through the Vernissage, the open-air market in a park along Aram and Buzant streets where there are stalls and stalls of ceramics, folk and contemporary art, rugs, textiles, jewelry and more. I bought two small antique Caucasian kilims before I wandered back to Republic Square, where I end most evenings.

At night the square, with its monumental rosy tufa stone buildings, is lit up; the fountains spew through colored lights, music plays, people dance. It’s a nightly ritual in Yerevan in the warm-weather months — a down-home celebration to end a day, and a resilient response to the harsh history of this new nation that has emerged from an ancient civilization.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Peter Balakian © 2018 The New York Times

via Nigerian News ➨☆LATEST NIGERIAN NEWS ☆➨GHANA NEWS➨☆ENTERTAINMENT ☆➨Hot Posts ➨☆World News ☆➨News Sp

#IFTTT#Nigerian News ➨☆LATEST NIGERIAN NEWS ☆➨GHANA NEWS➨☆ENTERTAINMENT ☆➨Hot Posts ➨☆World News ☆➨N

0 notes

Text

Opinion: An ancient land, newly optimistic

The downtown has an energy that is a long way from the sleepy Soviet city I first visited in the 1980s.

Each time I’ve come to Yerevan in the past decade, the city has surprised me with its evolving elegance and cultural richness.

The downtown has an energy that is a long way from the sleepy Soviet city I first visited in the 1980s. Walking the shady avenues off Republic Square on a recent visit, I found the city has become a hip place, with wine bars, microbreweries, cafes, art galleries, boutiques selling crafts and carpets, and an ever-new array of restaurants, as well as upscale hotels and clothing stores.

The new mood is defined by the millennial generation’s role in the velvet revolution of this past spring. After weeks of peaceful protests, the civil society has pushed from power an old regime that much of the nation viewed as dysfunctional and corrupt, representing a continuation of old Soviet mentalities. When Nikol Pashinyan, a prominent journalist, activist and former parliamentarian became prime minister May 8, a sense of a new era enveloped the country.

In June, I sat in a vine-trellised courtyard restaurant and art gallery on Abovian Street with Armen Ohanyan, a young fiction writer, and Arevik Ashakharoyan, a literary agent. I was hearing Armenia’s new voices of optimism. “Soviet minds are a thing of the past,” Ohanyan said.

“The new generation, born after the fall of the Soviet Union, is playing a big role in the new democracy,” Ashakharoyan said. “We are tech-savvy and have no ties to the corrupt Soviet past.”

Ohanyan added: “We feel a new future. The reign of oligarchs is over.”

Having written about Armenia for decades, their words resonated. I am a poet and nonfiction writer of Armenian ancestry and have been to Armenia five times in the past decade. My trips are often connected to my work — a translation of one of my books, a lecture tour, a symposium.

I started the day grazing on a classic Armenian breakfast spread at the Armenia Marriott Hotel Yerevan, an elegant hotel on Republic Square with fine local cuisine: bastermas (spicy, cured beef); paper-thin or thicker warm lavash; local cheeses; jams with strawberries or apricots or walnuts; thick yogurt; cherries, apricots, blackberries and melons from local orchards; fruit nectars and orange, red and brown rolls of thick grape molasses stuffed with walnuts (sujuk); and black tea from a samovar. The presentation was beautiful, and the Caucasian sun poured through the windows.

Like its cuisine, the country has a long, rich history. Armenia, which became an independent republic in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union, is a small, landlocked nation in the southwest Caucasus, at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. The country today is what remains of a once-ancient empire that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Caspian Sea in the first century B.C., before it was conquered by the Romans. It was the first nation to make Christianity its state religion, in 301.

Conquered by Byzantines, Persians, Mongols and Seljuks, then colonized by the Ottoman Turks in the 16th century, Armenians were subject to large-scale massacres in the 19th century, during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and were the victims of what genocide scholars regard as one of the first genocides of the modern era, by the Ottoman Turkish government in 1915. (Turkey denies that the killings were genocide.)

Armenia became a Soviet Republic in 1920, endured Stalin’s purges and repression, a massive earthquake in 1988 and a war with neighboring Azerbaijan in the 1990s that has flared up again in recent years over the province of Nagorno-Karabakh. By all rational odds, Armenia should not be on the map today.

Having survived such a harsh history, Armenia has emerged as a democracy that cherishes the many layers of its past. Today, the capital, Yerevan — which dates to the seventh century B.C. and was founded on the walls of the Urartian city of Erebuni — is a blend of ancient culture, artisan tradition, modern architecture and high-tech, postmodern style, exemplified by the new condominiums and high-end shops on the pedestrian Northern Boulevard.

On Sept. 29-30, Yerevan will celebrate its 2,800th anniversary, making it one of the oldest cities in the world. In the ruins of the ancient fortress on Erebuni Fortress Hill, fragments of murals with images of sacred animals evoke the late Bronze Age. The Erebuni museum has a fine collection of artifacts, including a huge wine storage container that documents Armenia’s winemaking tradition from the Bronze Age.

Those amphoras prompted me to visit the Ararat Brandy Factory, an imperial monument to the Armenian passion for the grape, set on a perch overlooking Victory Bridge, which spans the Hrazdan River. I love walking the beautifully lit cavernous halls filled with Caucasian oak barrels. Ararat Brandy has been a major export for more than a century, and its velvety depths were made legendary by Winston Churchill, who drank it daily for decades. I left with a glow of delight after the brandy tasting that concludes the tour.

Yerevan is a city where many avenues are named after Armenia’s great figures: the early 20th-century poet Yeghishe Charents, the fifth-century historian Movses Koranatsi, the 19th-century novelist Katchadour Abovian, the composer Komitas (1869-1935), to name a few. It’s a city of great museums, including the Matenadaran, which has a rich collection of medieval illuminated manuscripts and books in Armenian, the National Gallery and the History Museum of Armenia.

I always head first for the intimate museums dedicated to major figures. The Saryan museum, for example, has two floors of works by the avant-garde landscape and modernist painter Martiros Saryan (1880-1972). In a stately stone house, the Sergei Parajanov Museum is a celebration of the great 20th-century filmmaker and visual artist’s work: mixed media collages, paintings, conceptual installations and miniature drawings on matchbooks and bottle caps from the time he was imprisoned by the Soviet authorities for “decadent” art and homosexuality.

I always get a good workout climbing the 572 steps of the Cafesjian Center for the Arts (also known as Cascade). It’s a dramatic complex rising up from the tree-shaded, cafe-abundant Tumayan Street in five monumental limestone tiers of fountains, topiary gardens and sculptures. If you tire of the climb, you can slip inside and take the escalator, and soak up one of the most important collections of modern glass in the world, as well as paintings, drawings and sculpture.

No one should come to Yerevan without visiting the extraordinary Armenian Genocide Museum and Memorial, also known as the Tsitsernakaberd (meaning swallow’s fortress) Memorial Complex. It is situated on a hill that overlooks the city and Mount Ararat, Armenia’s national symbol, just across the border in Turkey.

Built of sleek gray basalt, its elegant new wing was designed by the museum’s director, Hayk Demoyan, and his wife, designer Lucine Matevosian. The wide circular exhibit halls wind from a top floor down to a second floor. Photos, maps and documentary footage on various screens accompany text that explores the history of the horrific events that took the lives of more than 1 million Armenians in 1915. From the museum visitors walk the stone walkway to the memorial — towering twin obelisks (a symbol of eternity) and 12 20-foot high stone pillars — to lean over a large circular area where an eternal flame burns and sacred music plays.

Back in Yerevan for the evening, I dined with friends and found the cuisine more inventive than ever. Restaurants blend the traditions of the Armenian Caucasus with the Middle East as refugees from Syria and Iraq make their impact. At Sherep, one of the hottest new places, with a chic open kitchen and late-night jazz, I had mountain sorrel soup; tender stuffed grape leaves; eggplant sautéed in olive oil and rolled up with minced walnuts, dill, garlic and yogurt; and succulent lamb chops. At Vostan, in an old Russian-period stone building on Abovian Street, I feasted on pink, succulent, wood-grilled Lake Sevan trout.

My travels frequently take me beyond Yerevan. Wherever you go in Armenia, you are journeying through an open-air museum where churches and monasteries, even a Hellenic temple, are built into the cliffs or perched at the edges of canyons or green gorges, with searing vistas framed by the ever-blue sky. Thousand-year-old lacelike carved stone crosses (khatchgars) emerge from fields of roadside poppies.

Because Armenia is defined by mountains, canyons, gorges, forests, rushing streams and rivers, lakes, grassy highlands and dales, it has become a prime destination for hikers. The new Transcaucasian Trail runs from Georgia through Armenia into Azerbaijan, and offers extraordinary trails from the Dilijan National Park in the northern mountains to the caves of Goris in the south. Many trails intersect with ancient monasteries and churches.

For a small country Armenia has an amazing diversity of flora and fauna; about 240 bird species breed in Armenia and nearly 400 move through the country, making Armenia a birder’s paradise.

On a sunny morning, I headed east from Yerevan in a minivan with my superb guide, Katar Taslakyan, and a driver, Raphael Hovakimyan, whose musical selections — jazz and R&B — filled the van. About 40 minutes later, we stopped at Charents Arch, an impressive monument to Armenia’s great modern poet Yeghishe Charents (1897-1937). From there, we got a stunning view of the glistening, grassy highlands and snow-capped Mount Ararat.

In another 15 minutes, we were at Garni, a beautifully proportioned Greco-Roman temple believed to have been built by King Tiridates I to the sun god Mihr. The vistas from Garni, which is perched at the lip of a gorge, are spectacular.

We drove on until the conical dome of Geghardavank (the Monastery of the Spear) emerges from behind a stone wall. A UNESCO World Heritage site (like many monasteries in Armenia), the medieval church was built partly out of the side of a mountain. Monks’ caves adorned with stone crosses and arches dot the cliff face. I walked into a chapel and stared at the animal carvings on the wall as light fell through the round opening in the dome, a feature in Armenian medieval churches that creates a mysterious dark light and a heightened sense of the cosmic. A stream from the mountain runs through a wall, and pilgrims and tourists pass their hands through it.

At Geghard, as with most Armenian medieval churches, you enter a distinctive organic architecture, in which building and carvings flow with the contours of nature. Unlike the Gothic cathedrals of Europe, these churches are smaller in scale and designed as intimate spaces. Here, you feel the stones are speaking to you, the light grazes you.

The next day, we drove south from Yerevan into the fertile Ararat Valley. In June, the apricot orchards are popping with Armenia’s bright yellow national fruit and the vineyards are green. On this clear morning, Mount Ararat rose from a bank of clouds and the hot sun was mitigated by cool breezes.

Farther south, in Vayots Dzor province, our van climbed the road to Noravank, a complex that includes two medieval churches, one of which was designed by the architect and artist Momik. Again, I’m blown away as monks’ caves appear in jagged red cliffs that remind me of Arizona, and the milky tan limestone of the Myrig Adzvadzeen church glistens in the sunlight against a brilliant blue sky and rising mountains. The chapel at Noravank is luminous with light pouring through the windows. Gazing out those windows to green hillsides, red cliffs, blue sky, I felt the shimmer of the sublime.

Four miles from Noravank, I went from spiritual to chthonic, as I walked up the steps of a craggy cliff to the Areni cave where, in 2007, the earliest known clay amphoras (karases) — some 6,100 years old — were discovered. Armenia is considered the birthplace of winemaking. Archaeologists are still working there, and the Copper Age karases are well displayed in the cave where they were once used.

Winemaking runs deep in the Armenian vein, and the famous Areni grape with its thick skin is the source of some of the best new wines anywhere. Throughout my visit, I had various full-bodied reds that were smooth and dry, with complex flavors enhanced by Caucasian oak barrels, reminding me of some fine pinot noirs of Oregon and certain red Burgundies. Among the better-known labels are Areni, Kadar, Kara, Trinity and Zorah.

After a night on the Goris River at Mirhav, a beautifully appointed inn with antique Armenian artifacts and rugs, we drove to 11,000 feet through a fantasia of chirping nightingales, swooping eagles and clouds lifting off the green valley to the world’s longest nonstop, reversible tramway to reach Tatev, a ninth-century monastery. As a Baroque concerto spilled through the tramway’s speakers, our glass car floated above villages and ancient churches, by cliffs and grassy mountains and past gliding hawks toward the monastery, with its two conical domed churches perched at the cliff’s edge.

Heading north past potato fields and farmlands, meadows of poppies and royal blue delphiniums, we drove up the western shore of Lake Sevan, one of the largest high-altitude lakes in Eurasia. Its turquoise water is a resort for bathers and fishermen, and an important source for fishing, irrigation and hydroelectric power. At a lakeside restaurant called Dzovadzots, I had a perfect whitefish soup.

A half-hour north, the ninth-century Sevanavank monastery, with its two small beautiful, earth-colored churches on a peninsula, is worth the climb up the steps from the shore below.

Just north of Lake Sevan, we crossed into the alpine mountain region of Tavush where streams and hiking trails wind through the lush forests of Dilijan National Park. The stunning monastery of Haghartsin is nestled on a forested mountain.

The spa town of Dilijan, situated in the park, is an atmospheric place out of a Chekhov story. Its chalet-style buildings with gable-tiled roofs, open-air theater and mountain views made it a popular vacation spot for wealthy Russians in the 19th century; today it is a retreat for artists. One of the creative entrepreneur and philanthropist James Tufenkian’s four unique hotels is housed in a complex of restored 19th-century houses.

From there, we drove to Avan Zoraget, another Tufenkian hotel, beneath the mountains on the Debed River. Sleek, imaginative and appointed with Tufenkian carpets, its rooms have lovely views. The restaurant overlooking the river offers a sumptuous repertoire: sautéed local greens and onions with yogurt; smoky eggplant dip blended with tahini; spelt with wild mushrooms; a tongue-melting sou boreg (thin flat noodles layered with Armenian cheeses), chicken cooked with dried plum and pomegranate sauce; and superb dry white wine.

Back in Yerevan the next evening, I walked through an arch onto an old cobblestone street off bustling Amirian Street and found Anteb, a Syrian-Armenian restaurant, where we had spicy, crepe-thin lahmajuns (Armenian pizza); a piquant muhamara (walnut, pomegranate molasses and red pepper dip) that you scoop up with hot, puffy lavash; and kuftas, crisp shells of cracked wheat bursting with lamb and herbs. The next night my friend Ashot took me to Babylon, an Arabic-Iraqi restaurant where our feast included crispy boregs (phyllo dough wrapped around cheese), meatless stuffed grape leaves and the most tender lamb kebabs I’ve had outside my mother’s kitchen.

I never leave Yerevan without meandering through the Vernissage, the open-air market in a park along Aram and Buzant streets where there are stalls and stalls of ceramics, folk and contemporary art, rugs, textiles, jewelry and more. I bought two small antique Caucasian kilims before I wandered back to Republic Square, where I end most evenings.

At night the square, with its monumental rosy tufa stone buildings, is lit up; the fountains spew through colored lights, music plays, people dance. It’s a nightly ritual in Yerevan in the warm-weather months — a down-home celebration to end a day, and a resilient response to the harsh history of this new nation that has emerged from an ancient civilization.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Peter Balakian © 2018 The New York Times

source http://www.newssplashy.com/2018/08/opinion-ancient-land-newly-optimistic.html

0 notes