#& it’s also just about general trends particularly in remakes & reboots

Text

“we’re taking out this problematic aspect because showing characters doing things the audience might not like could be uncomfy” “we’re taking out unnecessary side plots & making everything more mission centric” “these characters were pretty flawed in the original incarnation of this work so we decided to make them more palatable & the story more straightforward”

#media#tv#sanitization#this is not just about atla#I think it also heavily applies to pjo but don’t execute me#& it’s also just about general trends particularly in remakes & reboots#anti atla live action

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the most enjoyable thing to me about film review is how fluid it is. Not only is the medium, by nature, ever-changing, but with personal experience comes a shift in opinion that can change perspectives so much it requires a completely new piece. Though this work is not coming out of so drastic a change, it is coming out of a desire to rectify something put forward in my previous SAW review. Similarly, it is a statement of something core to my beliefs with all my reviews: that “bad” films are not always truly bad. Often, they’re quite enjoyable.

Now, I should put forward my frame of reference for this, in the form of two facts. The first: my current hyperfixation is SAW. The second: the only two SAW films I’ve seen are the original, and SAW 3D. Do with this information what you will, but I think it’s important to acknowledge that what I’m writing comes from a place of intense personal passion, and simultaneously intense disinterest. See, when I say SAW, I mean specifically Doctor Lawrence Gordon and Adam Faulkner-Stanheight. To a lesser extent, I am also fixated on the production, but that’s relatively common for me. The technical, visual aspects of a film are often just as important to my enjoyment of it as anything else— I’m more inclined to enjoy a film with physical effects and mechanics, both of which SAW has plenty.

This piece is serving as both an expansion on my original short blurb on SAW, and an acknowledgement that SAW 3D is not, as I put it, the horror equivalent of “a daytime soap opera.” It is, quite simply, a fun movie.

Do I have any background in any of the characters beyond Dr. Gordon himself? Not in the slightest— I’m coming into this movie with no expectations for how Hoffman or Jill Tuck should behave. This is, perhaps, a flaw of my own attention span. I tend to jump about through franchises: for years, I’d only seen the first and third Friday the 13th movies. I still haven’t seen the second or sixth Nightmare on Elm Street. My viewing history is filled with maybe somedays, films I’m certain I’d enjoy, most often part of franchises I know I like, but I just don’t have the motivation to sit down and watch them. Saw 2-6 and Jigsaw are part of this category.

What does that make SAW 3D, then? Lacking background in characters beyond Lawrence, whose appearance is unfortunately limited, what do I get from what was supposed to be the close of the franchise?

Not much, quite honestly.

SAW 3D is not a film rich in much. Beyond a trap made of an entire building which feels a little too poetic for Hoffman to have made (judging, again, by my admittedly-limited knowledge of the character), and an enjoyably gruesome trap made for a group of neo-nazis (I SQUIRMED watching this one!!!! SQUIRMED!!!! I can’t remember the last time I had to look away from a movie!!!!!! Even on a second viewing, I had to close my eyes at this part! Can you tell how exciting that is?), SAW 3D feels rather slapped together. I’ve heard as well that the director had no desire to actually direct the film, which makes things difficult.

What does a film do when saddled with an unwilling director? Its best, of course, and SAW 3D is still a valiant enough effort. Is it a masterpiece? Not by any stretch of the word, but it’s fun. This here is why horror is one of my favorite genres! SAW is a masterpiece of modern horror, a reflection of the magic of A Texas Chain Saw Massacre! A rarity! A gem! I couldn’t be more enthusiastic about this film. SAW even surpasses Texas Chain Saw in one area: the actors, director, and staff had fun making this movie! I will always sing praise for Texas Chain Saw; it is the film I consider the penultimate horror movie, unsurpassable in its legacy. It captured a sort of magic in how gut-wrenchingly horrific it is with such minimal blood: it’s all psychological.

As previously said, I feel that SAW captures that same magic. The film has minimal gore, a byproduct of its limited budget, but is remembered as much more brutal than it actually is— it became the springboard for a franchise absolutely drenched in disgusting moments. SAW 3D’s neo-nazi trap is chief among them, for me (that back glue? good GOD man....). Yet, where the cast of Texas Chain Saw have many painful, sweaty, exhausting moments to remember (the actor who played Nubbins was a veteran and has stated that his time working on Texas Chain Saw was worse than his time as a soldier), the cast of the original SAW had a blast, proven by an audio commentary filled with James Wan, Leigh Whannell, and Cary Elwes all poking fun at each other (and a ridiculously goofy Marlon Brando impersonation from Mr. Elwes — I genuinely can’t recommend the commentary enough).

Even separated completely from my personal passion for the film, it’s an amazing feat for me to sit here and say to you all that a film has, in one instance, surpassed for me my pinnacle of horror. How often does that happen?

Yet, I still haven’t completed my thoughts on SAW 3D. Circling back, I have to laugh. I’ve unintentionally mirrored my own Texas Chain Saw viewing pattern with my SAW viewings: for quite a long time, I’d only seen Texas Chain Saw and TCM: The Next Generation. If you’ve been here long enough, you’ve seen me mention TNG time and time again. To recap, for those of you who may be seeing my writing for the first time: it’s a genuinely HORRIBLE film. It is, however, a favorite of mine— enough so that I own it on DVD, now. TNG is a purposefully bad film, created with the intent of antagonizing the viewer and calling to attention our pattern of complacent viewership. In my original piece on TNG, I state that “my problem with modern horror is that it’s loud, the violence is gratuitous and charmless ... because supposedly that’s what a Modern Viewer [sic] wants. TCM4 takes these things, grinds your nose into them, and says ‘fuck you, you want this? here'” (source). Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation defies the conventions of modern horror in a deeply obnoxious, yet thought-provoking way. SAW 3D... does not.

SAW 3D’s greatest problem is, perhaps, that it’s exactly what audiences demand. Though I must admit the 3D is tasteful, and I’m grateful for that, the fact remains that the movie lacks innovation. While it doesn’t necessarily need to innovate as the close of a franchise, I ultimately think it’s ridiculous to have tried to close the franchise at all. As much as I hate the trend of reboots and remakes in the modern market, particularly modern horror, I must acknowledge that studios will milk a popular franchise for all that it’s worth, and sometimes more (I’m looking at you, SyFy Pumpkinhead sequels).

SAW 3D is the victim of an unfortunate situation. An over-saturation of SAW films in the market meant waning popularity, coupled with a fanbase still dedicated enough to want a finale, and a director lacking interest in the project (we all get tired of things, no matter how passionate we may be in the beginning— I hardly blame anyone for being tired of the franchise after the way they churned those films out). This isn’t to imply any of the films are bad, especially since I haven’t seen them! There is, however, an undeniable pattern to horror films which has persisted since the 70s and 80s: horror franchises tank after 3-5 films. Some are lucky, some less so, but the range of 3-5 films seems to be the golden one for horror. For a movie franchise, seven films is comfortably beyond that, and SAW 3D is misleadingly the seventh film.

For as much as I’ll happily sit down and watch it, SAW 3D puts nothing forward and asks nothing in return. A franchise that started with such a dramatic bang went out with a fizzle (or would have, if not for Jigsaw and the upcoming Spiral). It’s enjoyable to see the reverse bear trap used. It’s enjoyable to see Lawrence again, and to watch Hoffman lay on the ground and get poked (quoth the reviewer: get his ass, Larry). It’s... fun, but it’s cheap fun. It’s fast food horror. I’m happy to have it once in a while, but the late 2000s to 2010s were oversaturated with similar films. I want more from a movie meant to close out something as dramatically influential as SAW, something so enrapturing! Something which I can confidently say exceeds Texas Chain Saw Massacre in one important area! Damn it, the SAW franchise deserved better than this!

Maybe it’ll get it, with the Spiral reboot coming out. Maybe it won’t, who knows? I’m interested to see how Spiral plays out, and I have surprisingly high hopes. Between that and the Candyman remake, there are a lot of “re-” horror films I’m genuinely looking forward to. I haven’t felt this way about a horror re-anything since Evil Dead in 2013, and I’m feeling cautiously optimistic. We’ll see what the future holds — hopefully something that’ll be handled better than the original franchise was, though I don’t think Hollywood will ever learn to distinguish a dead horse from a live one. They’ll just keep beating and beating every horse in the stable. Perhaps I’m really a pessimist about all this, but again: personal experience. I’ll keep my cautious optimism up, and keep an eye out. I’m planning on watching Dying Breed and Cooties soon (two films with Leigh Whannell in them), so expect at least a short blurb on those two, and who knows? Maybe you’ll see something big about Spiral in the future. After all, if even a fizzle like SAW 3D can make me squirm even now, I think there’s a lot of hope to be had.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hardy Boys: Comparing Hulu’s Show to the Classic Book Series

https://ift.tt/37uI1um

First published in 1927, The Hardy Boys series of books created by Edward Stratemeyer has sold more than 70 million copies and been translated into more than 25 languages. The novels have been revised, rebooted, and reimagined at least four times since their debut and the eponymous characters have appeared in everything from comic books and TV shows to video games and cartoons.

Possibly the real mystery here is why there hasn’t been a television adaptation of this story on-air since the late 1990s, particularly when remakes and reboots have been all the rage for years. The CW currently has a hit Nancy Drew series on the air, and shows like Riverdale, Pretty Little Liars, and Veronica Mars have spent years reinforcing the idea that teenagers are surprisingly great at solving crimes. Whither, the Hardy Boys?

On Hulu, at last. This new adaptation of The Hardy Boys, starring newcomers Rohan Campbell and Alexander Elliot as the sleuthing siblings, is the fifth onscreen version of their story and its mere existence will be enough to delight some fans who just want to see their favorite characters come to life onscreen.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

But although this The Hardy Boys series is a perfectly serviceable family mystery with a charming young cast, fans of the original series of novels may find themselves surprised by some of the changes from the source material. Of which there are quite a few – for both good and ill.

Let’s run down a few of the most significant.

The Hardy Boys Are Younger Than Usual

In the Hardy Boys novels, as in the Hulu show, Frank and Joe Hardy are brothers. But in the world of the TV series, they’re actually much younger than any version of their fictional counterparts that have come before. In the books, Frank is usually eighteen and Joe is seventeen – though there’s one set of stories where they’re seventeen and sixteen, respectively – but in the show, the brothers are sixteen and twelve. It’s an interesting decision, particularly since TV adaptations like this (looking at you, Nancy Drew) generally tend to go the other way, aging up their protagonists so that they can take part in more adult stories.

Making the Hardy boys younger than ever before does allow the Hulu series to appeal to a wider audience than it might otherwise be able to do. But the sudden four-year gap between the brothers makes their relationship strangely complicated. They no longer feel like relative equals and, as a result, their friendship here is quite a bit different than it is on the page. And to be honest, although Bridgeport is indeed a weird town, the fact that a group of high school teens is apparently just fine with constantly hanging out with a twelve-year-old is more than a bit strange.

The Hardy Family Dynamic is Quite Different

In the Hardy Boys novels, Hardy matriarch Laura is presented as an example of the ideal stay at home mom. She generally has little to do on her own, though the updated 2005 Undercover Brothers series did finally give her a job. (In it, she is a librarian.)

In the Hulu TV adaptation, she is a dogged investigative journalist and an all-around great example for her kids. A daughter of an overbearing mother, she apparently rejected her life of privilege in Bridgeport to marry the boys’ father Fenton and follow her calling to find the truth.

Read more

TV

How Nancy Drew Has Reinvigorated the Dark Young Adult Drama

By Lacy Baugher

Unfortunately, however, she is also dead, and it is her apparent murder that sets her sons off on their path to become sleuths, as they work to solve this very close-to-home mystery. (Your mileage may vary regarding how you feel about the fact that Laura is basically killed off to drive emotional development for the men in her life.)

As for Fenton, he remains a big part of the story but is also strangely absent at the same time. Leaving the boys with his sister Trudy while he heads off to investigate his wife’s death, he seems to struggle with how to be the dad that Frank and Joe deserve. This is something of a shift from the novels, in which he is basically the dream ideal of a perfect father, so perhaps The Hardy Boys is meant as something of an origin story for Fenton, too.

Fewer Mysteries to Solve

In The Hardy Boys novels, Frank and Joe went on all kinds of adventures, traveling all over the United States and occasionally to far off locations like Mexico and Egypt in order to solve cases. In the Hulu adaptation, their story is almost entirely contained within the town of Bridgeport (clearly an analog to the Bayport of the books), where both boys are sent for the summer following their mother’s death.

As a result, a season-long mystery shapes up, albeit one with many moving pieces. As the boys investigate their mother’s death, they unearth dark family secrets, discover an object that may or may not have supernatural abilities, and reveal corruption within local institutions. But they’re not really solving mysteries in the way that many fans might have expected, and the series serves as something of an origin story for the pair as sleuths.

A More Diverse Central Ensemble

In many ways, the Hulu version of The Hardy Boys story has much more of an ensemble than any of its written counterparts do. In the novels, the Hardy boys are occasionally assisted in mystery-solving by a gang of (mostly male) friends, who don’t have much in the way of arcs of their own. In the Hulu adaptation, the brothers’ larger, much more diverse social group is directly woven into the fabric of the story the show is telling. (A trend which we can likely thank popular teen shows like Riverdale for.)

And though these characters are all based on figures from the novel, many of them are changed onscreen in ways that help modernize and update the story for a 2020 audience.

For example, Frank’s BFF Chet Morton is here reimagined as an earnest African-American farm kid; whereas in the novels he’s white, chubby, and obsessed with food. There, his non-athletic nature is usually played as comic relief, as is his love of the bright yellow “jalopy” named Queen he’s always working on. This TV version of Chet is much more of an everyman figure, a regular guy who loves small-town life in Bridgeport. He’s also dating Callie Shaw, which will probably be an issue at some point in the future since she’s Frank’s girlfriend in the books.

The decision to make Chet a young Black man is also a choice that feels particularly important, given the fact that the original books rarely feature characters of color and often include what we would now consider racist stereotypes of non-white people.

Female Characters Have Important Roles to Play

The fact that female characters don’t have much to do in The Hardy Boys novels isn’t really surprising – from a storytelling perspective, these books aren’t really meant for or aimed at female readers, after all. (And the folks behind them probably would have argued that if young women really wanted to read mysteries, well, we’ve got Nancy Drew for that. Which is likely what most of us read instead.)

Thankfully, the Hardy Boys TV show works hard to make space for female characters – and by extension, female viewers – in its world and, for the most part, it succeeds.

Callie Shaw, Frank’s generally nondescript book girlfriend, is here given an arc, a personality, and a story of her own. Technically, she’s not even Frank’s girlfriend yet, and though we all assume they’ll get together, it’s not a done deal. (Especially since she’s dating Chet.) But Callie has dreams of her own, which may not involve hanging on to boys from her small hometown.

As for the younger set, Joe’s very male best friend Biff Hooper is here reimagined as the tomboy daughter of the Bridgeport deputy sheriff. She is smart, brave, and loyal, and her burgeoning friendship with Joe is charming in a way that little else on this show is. Her mother’s occupation often creates very natural friction between the two and gives Biff a perspective of her own that can occasionally be at odds with her friends.

In Conclusion

Hulu’s The Hardy Boys is truly a strange specimen. As a series, it’s a perfectly decent family-focused mystery, but as an adaptation of the novels, it leaves quite a bit to be desired. Changing the brothers’ ages not only impacts their relationship with each other, it basically makes the series feel as though it has little in common with the original story beyond the characters’ names.

That said, the series’ vaguely 1980s-ish period setting does give it something of a timeless feel, which accurately reflects how many of us still see the novels. And this The Hardy Boys does add some long-needed elements to the franchise, like characters of color and women with arcs of their own. But it sort of forgets to get the part that really matters right – and that’s the brothers at its center.

The post The Hardy Boys: Comparing Hulu’s Show to the Classic Book Series appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/2VAI6XR

0 notes

Text

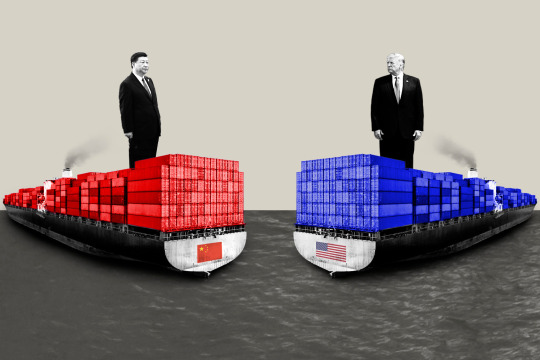

The Great Decoupling

Washington is pressing for a post-pandemic decoupling from China. But the last big economic split brought on two world wars and a depression. What’s in store this time?

U.S. and Chinese economic ties are fraying at the seams. But decoupling could have far-reaching geopolitical consequences, FP's Robbie Gramer and Keith Johnson write.

— By Keith Johnson, Robbie Gramer, May 14, 2020, Foreign Policy

The U.S. ambassador on the spot in an Asian economic powerhouse put it bluntly in a cable to the secretary of state in Washington: Don’t cut them off. Give them some “economic elbow-room,” or they’ll be forced to carve out an economic empire of their own by force. But Washington was in the grip of economic nationalists battling a historic economic downturn. The White House, consequently, was deaf to the Ambassador Joseph Grew’s pleas from Tokyo in 1935.

Within a few years, the United States ramped up economic pressure on Japan, culminating in a trade and oil embargo. Six years after Grew wrote his dispatch, the two countries were engaged in total war.

Today, American policymakers are consumed by the economic and geopolitical confrontation with another Asian heavyweight. And, as in the 1930s, economic decoupling is all the rage.

For the more hawkish members of the Trump administration, undoing 40 years of ever-closer economic relations with China and rolling back U.S. reliance on Chinese factories, firms, and investment was always the end game of the endless trade war—even before the coronavirus pandemic turbocharged Washington’s desire to disentangle itself from what many view as a dangerous economic bear hug. Now, lawmakers and administration officials are mulling a raft of measures to cleave parts of the two largest economies in the world: Bans on a wide variety of sensitive exports, additional tariffs on Chinese goods, forced reshoring of U.S. companies, even pulling out of the World Trade Organization altogether, which is seen by some as facilitating China’s so-called economic imperialism.

It’s not just economic ties between China and the United States that are in danger. Europe, too, is increasingly talking of rolling back the deep trade and investment ties it has developed with Beijing in recent decades (even as it is cutting trade ties with itself, as the United Kingdom leaves the European Union). Other countries are also pulling up the drawbridges—all leery that today’s unprecedented level of economic integration has gone too far, bringing more pain and less gain.

The threat of a great decoupling is a potentially historic break, an interruption perhaps only comparable to the sudden sundering of the first huge wave of globalization in 1914, when deeply intertwined economies such as Britain and Germany, and later the United States, threw themselves into a barrage of self-destruction and economic nationalism that didn’t stop for 30 years. This time, though, decoupling is driven not by war but by peacetime populist urges, exacerbated by a global coronavirus pandemic that has shaken decades of faith in the wisdom of international supply chains and the virtues of a global economy.

Other countries are also pulling up the drawbridges—all leery that today’s unprecedented level of economic integration has gone too far.

The only real question is how far the decoupling will go. U.S. President Donald Trump made one of his sharpest threats to date amid growing tensions with China in an interview with Fox News on Thursday. “We could cut off the whole relationship,” he said—a prospect that, while unlikely if not practically impossible, would send historic shockwaves through the global economy.

Undoubtedly, most experts and officials agree, brewing trade tensions between Washington and Beijing—amplified by the coronavirus pandemic—will force some multinational companies to alter their business models, reorienting their supply chains closer to U.S. shores. Across the fractious political spectrum in Washington, Republicans and Democrats alike agree the United States should alter its business relationship with China to varying degrees. But if the fallout from the pandemic passes quickly, and especially if Trump and his protectionist “America first” agenda are defeated in the November election, the clamor to decouple from China could begin to ebb as politicians confront just how complex it is to untangle parts of the world’s two largest economies. Not least of the problems Washington would have to confront is that China is the second-largest U.S. creditor, holding more than $1 trillion in U.S. debt.

Either way, the looming reshaping of the sinews of the world economy will have untold implications, from tearing up business models to remaking entire industries. But it could also have unforeseeable geopolitical consequences, especially regarding China, which over the course of four decades has grown from minnow to whale under the auspices of a tight-knit global economic system, led by deepening trade and investment ties with the West. What happens if that gets torn apart?

“There’s enough there by way of trend lines to suggest we’re entering into a new period that turns on its head the widely-held assumptions about the U.S.-China relationship from the time that Deng Xiaoping returned to leadership in the late 1970s and rebooted China for the subsequent 40 years,” Kevin Rudd, a former Australian prime minister and well-known China scholar, told Foreign Policy.

He worries about, if not a straight replay of the first Cold War, which featured bigger nuclear arsenals and proxy wars around the globe, at least Cold War 1.5. “It’s at that sort of inflection point,” he said.

That could spell the reemergence of competing blocs, as during the Cold War. China is already well into the creation of its own economic sphere with its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, which seeks to link economies across Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe to Beijing. China and the United States are on track to develop dual, and dueling, technology to drive the next big economic transformations, especially in mobile phones.

Now, Trump administration officials talk of rolling out a concept called the “Economic Prosperity Network” of like-minded countries, organizations, and businesses. The aim is in part to convince U.S. firms to extricate themselves from China and instead partner with members of the so-called network to reduce U.S. economic dependence on Beijing—seen as a key national security vulnerability. If a U.S. manufacturing company can’t move jobs from China back to the United States, for example, it could at least move those jobs to another more U.S.-friendly country, such as Vietnam or India.

“Safeguarding America’s assets is one of the core pillars, supply chains are a big part of that,” Keith Krach, Trump’s undersecretary of state for economic growth, energy, and the environment, told Foreign Policy. “Supply chains are super complex. Sometimes they go down 10, 20 levels and I think it’s essential to understand where those critical areas are, where the critical bottlenecks are,” he added.

How will Beijing respond? China, in some ways, has been pursuing its own form of decoupling for more than a decade, since it launched a campaign to develop more advanced technologies at home and rely less on U.S. and other Western suppliers, noted Ashley Feng of the Center for a New American Security. And many Chinese firms have proved adept at surviving a rupture with the United States—Huawei, for example, once relied on U.S. firms for many of the components of its smartphones but now does without. Still, China’s quest to bolster its own capacity for innovation and to become a leader in advanced technologies relies on easy access to firms and researchers around the world, and it doesn’t want to see those connections severed entirely. At the same time, with an already-slowing economy hammered by the pandemic this year, China will likely do what it can to ease the economic tensions with the United States—like trying to appease Trump by adhering to the goals of the phase-one trade deal reached in January, for example.

“The economy has been deeply damaged by the coronavirus crisis and, prior to that, damaged somewhat by the trade war,” Rudd said. “So I think the predisposition of Beijing at present to try to restabilize that economic relationship because China is still not strong enough to sail alone.”

Decoupling refers to the deliberate dismantling—and eventual re-creation elsewhere—of some of the sprawling cross-border supply chains that have defined globalization and especially the U.S.-China relationship in recent decades. The modern version of the concept traces back, ironically, to Chinese policymakers in the 1990s who were themselves worried about overdependence on the U.S. dollar and high-end American technology.

Trump has long contended that China has exploited the U.S. economy for its own enrichment at the expense of the American worker, and there is some economic data to back that up. As a result, since taking office, the Trump administration has sought to partially decouple economically from China, first by reducing U.S. imports through higher tariffs, later by more restrictive screening of Chinese investment in critical sectors.

More recently, the administration has expanded controls on exports to China of potentially sensitive technologies, and this week it banned a federal retirement fund from investing in Chinese stocks. Administration officials even briefly flirted with the idea of defaulting on government debt held by China. These days, efforts to tear up and rebuild supply chains are gaining momentum, whether in semiconductors, rare-earth elements, or medicines and personal protective equipment needed to deal with the ravages of the coronavirus pandemic.

“What the pandemic has done is expose our very significant dependence on Chinese production, and overseas production generally, but particularly in key areas on Chinese manufacturing production and Chinese supply chains,” said Sen. Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican, who is leading the legislative charge to repatriate U.S. supply chains and withdraw from the WTO. “I’d like to see as much production brought back to our shores as we can.”

“What the pandemic has done is expose our very significant dependence on Chinese production.”

Other U.S. allies around the world are eyeing ways to follow suit. Australia, bristling at Chinese trade threats, is also looking to diversify its own export markets and supply chains away from China. Europeans are having second thoughts about ever-closer trade and investment ties with Beijing. Some European policymakers in recent years have been spooked by an aggressive wave of Chinese takeovers of critical infrastructure from ports to power grids, fearing it could give Beijing undue leverage over their countries. Chinese diplomats have taken on an aggressive stance against some Western countries, including the Netherlands, with vague threats of sanctions or other forms of coercion as relations sour amid the pandemic.

“Many countries are waking up to this aggressive tactic and they don’t like it. The damage to China’s reputation is irreparable,” said the State Department’s Krach.

The CEO of Axel Springer, a major German media company, recently made the case for Europe to “draw a clear line in the sand” and follow the U.S. lead in rolling back economic relations with China. “If we do not manage to assert ourselves, then Europe could suffer a similar fate to Africa, on a gradual descent towards becoming a Chinese colony,” Mathias Döpfner wrote.

The trend also transcends politics, meaning decoupling could outlast the Trump administration. His presumptive Democratic presidential rival, Joe Biden, is a trade and foreign-policy centrist. But he is increasingly pressured by progressive populists, including supporters of Sen. Bernie Sanders, to move his trade and economic policies further to the left. Biden this week announced joint “unity” task forces of his top aides and Sanders supporters to develop a unified Democratic platform. Sanders has called for renegotiating trade deals with China aimed at bringing manufacturing jobs back to the United States and labeling Beijing as a currency manipulator. At the same time, Republicans are hammering the former vice president for being soft on China to lay the groundwork for a contentious election cycle, where China and the coronavirus pandemic will be central issues.

To a large extent, the current race to decouple is the fruit of two decades of steadily growing Chinese economic might, which many, like Trump, see as responsible for the hollowing out of important industries such as manufacturing in the West. Chinese state-owned companies, often powered by government subsidies and greased by a free hand with others’ intellectual property, have unfairly competed with companies in the United States and other developed economies since China joined the WTO in 2001, those critics say.

“The status quo ante was unsustainable because it presumed that China would eventually change the way it manages its economy, to bring it more in line with U.S. and European expectations,” said Dani Rodrik, a professor of international economy at Harvard University’s Kennedy School. “I think that was probably an implausible expectation even at the beginning, and clearly has been proven wrong.”

“The United States and Europe have genuine concerns,” he said. “It’s entirely legitimate, just as China wants to protect its own policy space, for us to say, I want to ensure I adequately protect my labor market and my innovation and technologies.”

While many point to China’s accession to the WTO as the original sin in the developed world’s economic relationship with Beijing, others maintain that it has been broadly positive for U.S. interests.

“What many critics overlook is that China already had access to U.S. markets. The United States didn’t give up anything—China made concessions to join” the WTO, said Robert Zoellick, U.S. trade representative in the George W. Bush administration at the time China joined the WTO.

“This is a theme, a new piece of the conventional wisdom, that cooperation has failed—and that assumption is flat wrong,” he said. “On proliferation, the global financial crisis, the environment, security—there are a lot of areas where cooperation has served U.S. interests.”

“This is a theme, a new piece of the conventional wisdom, that cooperation has failed—and that assumption is flat wrong.”

Those arguments never swayed Trump, however, who hasn’t strayed from his long-held gut beliefs that liberalized trade with China would ultimately come back to bite the United States—which he developed well before he became president in 2017 or before the coronavirus pandemic arrived. “Because China’s going bad it’s going to bring us down, too, because we’re so heavily coupled with China,” Trump told Fox News in an interview in 2015. “I’m the one that says you better start uncoupling from China, because China’s got problems.”

If skepticism of the merits of deeper economic relations with China was already rampant, the outbreak in China of the novel coronavirus has pushed that desire to decouple from Beijing into overdrive. China’s central place in many global supply chains came back to haunt the global economy when the world’s workshop shut down earlier this year, sending ripple effects throughout Asia, Europe, and North America.

Robert Lighthizer, the current U.S. trade representative, argued this week in the New York Times that offshoring of U.S. jobs was a “misguided experiment,” one whose vulnerabilities the pandemic has left in sharp relief.

“The pandemic has vindicated the Trump trade policy in another way: It has revealed our overreliance on other countries as sources of critical medicines, medical devices and personal protective equipment,” he wrote.

But the aftershocks of the outbreak affected more than just medical supplies Automakers, electronics-makers, and factories of all sorts struggled to keep operating after parts of China went into economic hibernation earlier this year.

“One province of China went on lockdown, and suddenly factories all over the world don’t have supplies,” said Beata Javorcik, the chief economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. “That drove home the point of how reliant we are on China, and how little redundancy we have” built into global supply chains.

Beyond that, persistent questions about Chinese President Xi Jinping’s alleged efforts to disguise the origins and outbreak of the new coronavirus have only deepened convictions of Sinophobes that the United States is too cozy with what is, and will remain, an opaque and undemocratic political system.

So Trump administration officials are seizing on the pandemic to ramp up their existing efforts to decouple economic relations between the world’s two largest economies. Before the pandemic struck, the Trump administration was in the midst of drafting a first-ever Economic National Security Strategy, reflecting the administration’s increasingly blurred lines between economics and national security. The pandemic has added new urgency to the task, several officials say, as it laid bare U.S. interdependence with its geopolitical rival, from technology in critical infrastructure to the supply chains for life-saving medical equipment.

One reason that the pandemic is creating such an opening for a fundamental reshaping of the global economy is because most of the economy, in the United States and elsewhere, has been shut down for the first part of the year. That creates a rare, if traumatic, opportunity to start with something like a clean slate.

“When you’re at a high level of economic activity, when unemployment is low, you’d see the pain if you pull all that apart,” said Douglas Irwin, an expert on trade history and policy at Dartmouth College. “But now that everything is scrambled, it’s easier in some sense to pull back. This artificial contraction makes it easier not to go back to how things were before.”

Global supply chains came about in the first place because they offered lower costs and greater efficiencies for manufacturers—to the benefit of consumers nearly everywhere, if not to certain displaced manufacturing workers. And many companies continue to invest in China not as a source of global production, but to serve one of the world’s biggest consumer markets—witness Tesla’s mammoth factory in Shanghai to churn out electric cars for the Chinese market.

To reverse that underlying business logic, governments can turn to policy that encourages or even forces businesses in certain sectors to relocate their manufacturing facilities, or investors to reconsider pouring money into China. The Trump administration has used national security arguments to levy tariffs on foreign goods, including Chinese goods, in a bid to force suppliers to relocate their factories. It can also reach for more powerful tools, such as the Defense Production Act and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which would allow the government to mandate some production decisions for the private sector. At the same time, the Trump administration has intensified the screening of inbound Chinese investment to keep Beijing from snapping up valuable advanced technologies.

Lawmakers and administration officials, however, still hope that a combination of factors will help drive companies to overhaul the way they’ve done business in years past: firms waking up to the political and reputational risks of doing business in China, bottom-line calculations about economic harms caused by China’s cover-up of the outbreak, and old-fashioned patriotism. (Several administration officials said they spoke to leaders of some companies who expressed a willingness to take short-term financial hits to divest from China, but they declined to name the companies.)

“The experts guffaw when you talk about manufacturing. They say, ‘Oh, that’ll never come back.’ Manufacturing is not monolithic.”

There are some signs of cooperation from other companies already: Big semiconductor-makers such as Intel are warming up to the idea of rebuilding high-end manufacturing capacity in the United States to serve government and private-sector customers. Other companies, stung by interruptions even with close neighbors such as Mexico during the shutdown, are also accelerating their efforts to reshore production.

“You’ve got producers, manufacturers, folks who produce things who are tired of having too much of their other inputs … tied up with Chinese and other supply chains,” Hawley, the Missouri senator, said. “They’d like to have more control over that.”

But if governments are getting ready to push, they are leaning in many cases on an open door. It’s not just populism or the pandemic that is rewriting the business logic behind global supply chains and rampant globalization. What once seemed like one-off external shocks that disrupted global production, such as the 2011 tsunami in Japan and flooding in Malaysia, are becoming increasingly frequent, thanks to climate change and extreme weather events. The pandemic and its disruptions just brought home the value of having a robust, not simply cheap, supply chain, Javorcik said.

“My point is that going forward, companies will be judged by rating agencies, by their shareholders, based on resilience. So there will be this powerful incentive for firms to change their supply chains, to build in redundancy, to build in some geographic diversification,” she said.

The first wave of decoupling will likely take place in medical supply chains, a vulnerability highlighted by difficulties getting masks, gloves, and even ventilators during the pandemic. And supply chains in many advanced technologies, from telecommunications to semiconductors, are also being reshaped for security reasons. Advocates of decoupling like Hawley hope the trend will expand to include broader swaths of manufacturing.

“The experts guffaw when you talk about manufacturing. They say, ‘Oh, that’ll never come back.’ Manufacturing is not monolithic,” Hawley said. “There’s lots of precision tooling, high-tech manufacturing going on around the world. We design many, perhaps most of the products that require that type of manufacturing, but we don’t make any of the tools or the finished goods here, and I’d like to see us do both.”

Companies are indeed starting to bail out of China, moving production both to other Asian countries such as Vietnam and back to the United States. The consultancy Kearney found in its latest Reshoring Index that manufacturers are increasingly diversifying their supply chains away from China, leery of the risks of the trade war—and now the pandemic. And large investors and money managers are increasingly starting to judge companies by the resilience and diversification of their supply chains.

Of course, the great decoupling on the horizon won’t be cost-free. Some firms that reshore production to higher-cost countries, such as the United States, will lose some of the efficiency gains they’ve racked up in recent decades. For many industries, the protectionist push could hit a very thick wall of opposition from corporate boardrooms very quickly, even with a raft of new incentives and warnings coming from Washington.

“There are going to be other industries that, while kicking and screaming, may ultimately move away from China and move business to another country.”

“Broadly speaking, I think companies are going to be incredibly resistant to anything that hurts their share price,” said Shehzad H. Qazi, the managing director of the China Beige Book, a platform that analyzes data on China’s economy for investors. “We’re not going to see, for example, Nike move all its production back to the United States and have their shoes and athletic wear being produced here, just because from a cost standpoint that makes absolutely no sense,” he said. “I don’t think there is any amount of tax incentives that could be provided that would be palatable enough to make that shift happen.”

Still, decoupling could be easier, or at least less painful, on a small scale for some industries than for others. “There are going to be some industries where it’s going to be virtually impossible no matter what,” Qazi said. “There are going to be other industries that, while kicking and screaming, may ultimately move away from China and move business to another country.”

At the same time, a race to bolster economic self-sufficiency in one country will almost certainly lead other countries to do the same, which could choke off export opportunities and lead to less trade in the future.

“Some of the lessons of the 1980s about just-in-time manufacturing will be adjusted—that is natural and appropriate,” Zoellick, the former U.S. trade representative, said. “We just have to decide where we want to pay the cost—because there will be costs. If we develop it all at home, it will have costs, and it will have costs for U.S. exporters” who stand to lose overseas access in a world of rising trade barriers, he said.

If the idea of a wholesale decoupling is so jarring, that’s because much of the last 80 years has been a deliberate, often U.S.-led effort to deepen, not weaken, economic integration around the world.

Washington made an open and increasingly interconnected world economy a key building block of the postwar architecture, in large part to explicitly stave off future global conflicts. With the creation of the Bretton Woods system in 1944, before World War II even finished, or the later creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade—forerunner to the WTO—it set out to link economic interdependence with peace. So did others: The European Coal and Steel Community, created just a few years after the end of the war, cemented both closer economic and security ties in a war-ravaged continent and lay the foundation for the eventual creation of the European Union. Those trends continued, decade after decade, with only the odd hiccup or retreat, from the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the WTO to the expansion and ever-closer economic integration between EU member states.

That whole process was itself a reaction to the last great decoupling: the upheaval of World War I, which ended the first age of globalization, followed a decade later by the Great Depression, trade barriers, economic nationalism, and a full-scale retreat from globalization.

And the end result of all that was to turn international economic rivalry into a zero-sum, beggar-thy-neighbor contest where economic concerns became security threats. Japan’s need for raw materials led to its occupation of Manchuria, and later the creation of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” that so worried Ambassador Grew during the 1930s. It eventually led to an attack on resource-rich Southeast Asia and a preemptive strike on the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. Nazi Germany, largely cut off from global markets, sought, eventually by force, to create a European Großwirtschaftsraum, or greater economic area, the economic equivalent of the German expansionist concept of Lebensraum.

“The key lesson drawn from the inter-war experience was that international political cooperation—and an enduring peace—depended fundamentally on international economic cooperation,” noted the WTO. “No country absorbed this lesson more than the United States.”

That’s what makes today’s deliberate retreat alarming to contemplate for some economists. “The importance of decoupling, it seems to me, is something that goes beyond” the modest retrenchment in global trade and global supply chains in the decade following the 2008-2009 financial crisis, said Rodrik, the Harvard economist. “It’s an approach to trade that is much more mercantilist and zero-sum, rather than positive-sum.”

When it comes to China, “What we need to worry about when we talk about decoupling is kind of using economics as a stick,” Rodrik said, “making the economic relationship hostage to the geopolitical competition.”

“You won’t have the globalization you had in the past. How far you down the road in reversing that is to be determine.”

Does that mean, as trade barriers rise and decoupling accelerates, that the world is headed for a repeat of the 1930s?

“I think there are some quarters in the United States that really do want to go that far, and I think other countries have to adopt a defensive posture,” said Irwin, of Dartmouth. “When some countries go down this road, it forces other countries to go down this road as well, and give up some of the gains they might have from being open and integrated. So these things can spiral—that’s certainly the story of the 1930s.”

But in some ways, such a repeat seems nearly impossible, because globalization, trade, and cross-border investment have advanced so much further today than when the Great Depression hit.

“I think the argument against is that today we have such a high degree of integration, there’s no way that Australia and Canada and the EU would go as far as the United States would, or no desire to go as far as the United States could,” he said. The upshot would be a retrenchment—not another dark valley.

“You won’t have the globalization you had in the past. How far you down the road in reversing that is to be determined,” he said.

Zoellick, for his part, ticks off the impacts already attributable to the pandemic and national lockdowns: rejiggered supply chains, export restrictions, constricted trade finance, and a resurgence of classical protectionism.

“I’m not sure anyone can say how they will all add up, but the direction isn’t good,” he said.

“I’m not trying to say we’ll return to the 1930s, but if you have an economic downturn exacerbated by pandemic risks and moves toward economic autarky, it can get pretty nasty,” Zoellick said. “So don’t take things for granted.”

Now that the Trump administration is using the coronavirus pandemic to more aggressively push its economic decoupling agenda, the big question is what happens to U.S.-China relations.

The United States has already thrown out the idea of strategic engagement with China and openly treats Beijing as its major geopolitical rival. China has taken advantage of the pandemic to ramp up pressure on Taiwan, which it regards as a renegade territory. Weakening the economic ties that bind—through more than $650 billion in annual two-way trade, tens of billions more in investment, and China’s trillion-dollar holding of U.S. government debt—will simply sharpen that confrontation.

“What we have now through the beginnings of economic decoupling is the removal of that economic ballast in the U.S.-China relationship, which has historically differentiated it from the characteristics of the U.S.-Soviet relationship in the Cold War,” said Rudd, the former Australian prime minister.

“If we have another pandemic, or environmental issues, or financial-sector issues, or Iran, or North Korea, how effective are you going to be if you don’t have a working relationship with China?”

In concrete terms, that will likely make it harder for the United States to nudge China to make any of the reforms Washington has pushed for years, let alone to moderate its increasingly belligerent and aggressive foreign policy. “If the question is whether breaking economic ties will lead to increased friction, the answer has to be yes,” Zoellick said. “The nature of decoupling doesn’t mean the Chinese will stop” their disruptive behavior, “they will just be less concerned with norms that the United States would otherwise push.”

In other words, after almost two decades of urging, sometimes successfully, China to become a “responsible stakeholder” in the global system, as then-Deputy Secretary of State Zoellick famously urged in a 2005 speech, the United States would essentially be throwing in the towel. And, on a host of global challenges, giving up influence and engagement with the world’s largest population, second-largest economy, and a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council could undermine U.S. interests across the board, he warned.

“If we have another pandemic, or environmental issues, or financial-sector issues, or Iran, or North Korea, how effective are you going to be if you don’t have a working relationship with China?”

And unlike other U.S. foreign-policy challenges in the Trump administration—from Iran to Saudi Arabia to Venezuela—any change to a Democratic White House next year would likely do little to dial down the confrontation with China.

Strategic engagement, which guided successive U.S. administrations since practically the first secret Richard Nixon-era trips to China, has been declared dead even by former Obama administration officials. With unemployment at record levels and the economy slumping, nobody—and especially not presumptive Democratic nominee Biden—wants to go easy on China. And many of the Trump administration’s economic policies toward China, from the reform of foreign investment to export controls to the remaining tariffs on Chinese imports, would be politically tough to undo with the stroke of a pen, noted Feng of the Center for a New American Security.

“There’s a bipartisan hardening—that tendency to be more hawkish on China, it has only been exacerbated by the pandemic,” she said.

In the end, U.S. efforts to roll back the one part of globalization that it can somewhat control—global supply chains and trade—will be at best a partial and imperfect solution that will only aggravate the other challenges. Choosing economic decoupling as the answer to today’s problems, said Zoellick, is simply inviting future headaches.

“If you try to stymie the system in one area, the forces of globalization—whether pandemics or migration—they are not going to go away,” he said. Gum up the global trading system, and you dampen growth prospects for the developing world. Lower growth leads to more migration. More migration leads to more political stresses in the developed world. “It’s like squeezing a balloon,” he said.

— Keith Johnson is a senior staff writer at Foreign Policy. Twitter: @KFJ_FP

— Robbie Gramer is a diplomacy and national security reporter at Foreign Policy. Twitter: @RobbieGramer

0 notes

Text

Music Review: Thom Yorke - Suspiria (Music for the Luca Guadagnino Film)

Thom Yorke Suspiria (Music for the Luca Guadagnino Film) [XL; 2018] Rating: 3.5/5 “When you dance the dance of another, you make yourself in the image of its creator.” – Madame Blanc Although it’s a stale, “get off my lawn” sort of take (recently achieving peak snub by being mocked in a recent SNL bit), it is nonetheless worth insisting that the remake/reboot trend has gotten decidedly out of hand. Greenlight bets are so hedged now that the marketplace of ideas has been subsumed by the plain old market. That the main target demo is the Comic Con obsessive who’d be most likely to bemoan the trend is especially frustrating. When it becomes about wanting to see what a renowned auteur will do with a genre classic, as is the case here with both film and soundtrack creator, we are ignoring and negating the very possibility that these heralded progenitors might have something fresh and lasting to offer us. Of course, if the remake makes money, they might then have the resources/freedom to go forth and create that new staple. It’s nice to think that the gloriously batshit mother! might’ve been possible thanks to Bible thumper money, but Noah wan’t exactly God’s Not Dead. I’m sure those weird helper-giant creatures Noah enlisted for Ark-building had even more impressionable Christians double-checking their Book of Genesis. Point is, it’s a legitimate gripe. At least to this media fiend. And that’s regardless of whether or not we’re supposed to move on in the face of the cutthroat circus that showbiz is and always has been. The massaged notion of the reboot as generational collaboration is reassuring — that is, until we realize it’s a sort of cashing out on the future. Rather than carrying a torch, art patronage has increasingly succumbed to stultifyingly obvious business model imperatives, even daring to call it “inclusive.” And the best these second passes can offer (though it’s decidedly rare) is improvement. In the case of IT, we’re talking God’s work. In the case of Suspiria, I fear for the deserved reverence for Argento’s singular, if imperfect, vision. Sometimes conversations around this cannibalizing of genre greats feels overeager and almost nihilistically dismissive. Hell, even if last year’s IT remake is both better and more expansive than the original TV movie, its eclipsing snuffs out an iconic (arguably superior) performance by Tim Curry as Pennywise. In this light, despite the promising trailer, one partly hopes Luca Guadagnino’s remake comes up short. But going on this soundtrack from raffish up-and-comer Thom Yorke, it might just be something completely different. That is, it might be the best witch-themed film since 2016. Clearly it will be slicker than its namesake, for better or worse. But where Goblin’s soundtrack is all raging menace and badass prog, Yorke’s is (surprise!) mournful balladry and icy, texturally rich reverberations. Discordant horror strings may be old as Vlad, but they retain their potency here. And while this record has a lot of appeal for Radiohead fans, the more song-oriented material never feels out of place from the creepier passages. There are also subtly grooving segments that recall bandmate Johnny Greenwood’s elevating score for You Were Never Really Here. And the repeated waltz theme (“Suspirium”) has the feel of a Moon Shaped Pool track, but in its recurrence accumulates a staying power that was absent for anything on that release. All told, Goblin’s soundtrack works better as an album. It is decidedly more singular, concise, and fun. At a staggering 25 tracks, Thom Yorke’s seems a likely candidate for digital dismemberment. As gorgeous and misstep-free as it is, the soundtrack risks a bit of that souvenir, collector’s item feel native to score-based soundtracks. That being said, it’s nowhere near as padded-out as those typically are. While melodies and tones recur, track to track, it plays out with an ear toward immersion (which advocates against streaming, wherein the transitions get butchered). Especially having not seen the film, this release comes across as an enthralling journey unto itself, ultimately dodging obligatory companion piece status. It’s solid enough that Guadagnino could only disappoint. In that sense, fans of eerie mood music and Yorke alike can’t really lose here. Two-minute songs that you’d expect to be slight present unexpected turns that make them feel epic. Only a few tracks contain movie-sourced sound, and — running against the grain of that sort of thing — the samples are not dialogue centered. While it could be tempting to call nepotism on the maestro featuring his son’s drumming in “Has Ended” and “Volk,” his contributions are superb (especially the staggered fills on the former). It’s impressively laid in the cut, particularly given the high-stakes stoicism of the surrounding material. The proper vocal tracks (the vox for the deep dive of “A Choir of One” are just layered moaning intonations), which retain the vital quality of the best Yorke/Radiohead compositions, stick out a lot more. But they work well, like gulps of waning daylight in a vast, inky oubliette. If I had to guess, these songs are used diegetically or just in the closing credits. Much remains to be seen, but there is the auspicious sense that this was more than just a gig for Yorke. He is dancing outside of Argento, rather than of him. If Guadagnino, for his part, is doing likewise, then the Giallo legend’s masterwork of extraordinarily garish sight and sound is all the better for it. And if Suspiria is as much of a distinct entity as this soundtrack suggests, it’d be nice to see the notion of “fuckin’ shit up from the inside” of a bankrupt industry actually pan out for once. http://j.mp/2EIBwJ7

0 notes