Text

Fashion in the time of COVID

WILL THE PANDEMIC LEAD TO A MORE ETHICAL, SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRY?

"We went way too far. Our reckless actions have burned the house we live in. We conceived of ourselves as separated from nature, we felt cunning and almighty. We usurped nature, we dominated and wounded it."

Alessandro Michele, Creative Director of Gucci

Gucci's creative director Alessandro Michele posted 1,200 words of poetic, impassioned diary excerpts on Instagram, making one thing abundantly clear, Gucci, and possibly the fashion industry as a whole would never be the same again.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the fashion world hard, gravely impacting all of its global capitals. Even before the virus struck, the industry was ailing. What happens now that no one's compelled to dress up from the waist down? And with our precarious place in the world coming into sharp relief, shopping for season “must-haves” seemed not only frivolous but immoral.

In March, Vogue partnered with the Council of Fashion Designers of America to set up A Common Thread, a pandemic-relief initiative that has raised $4.9 million to date. By May, more than 1,000 companies applied for aid, with even the biggest names on the precipice of an uncertain future.

In the interest of damage control, there has been industry talk of pushing the unreleased 2020 collections to 2021. It's curious that this requires we literally disavow the concept of fashion itself; that amorphous behemoth that tells us whether midi skirts are in or out this season.

With no end in sight to this state of flux, could this be an opportunity for the industry to ask itself some serious existential questions?

THE PROBLEM WITH FASHION

"We didn't respect the planet until now and in a way this [pandemic] is a message and unfortunately it's a very, very heavy message. Change had to be done. Everyone thought that the change would happen gradually, but that's not the case. Change has to be done now, and done quickly."

Sara Maino, Deputy Editor in Chief of Vogue Italia

Before the fashion world spiralled out of control, you had four seasons in the four major fashion capitals - London, Paris, New York and Milan. But the emergence of fast fashion accelerated the situation to a dizzying degree. Brands were sucked into the vortex of insatiable consumer demand. The pressure on luxury and high-street alike to drop new trends at higher speeds and lower costs had designers in a hamster wheel trying to outpace the copycats. "We were out of breath", admits Gucci’s Alessandro Michele, referring to fashion's unrelenting schedule of up to eight collections per year.

In her book, 'Fashionopolis: The Price Of Fast Fashion And The Future Of Clothes', Dana Thomas takes an unflinching look at the catastrophic environmental and human cost of this obsession with newness. Fast fashion refers to the production of masses of cheap, trendy clothes at breakneck speeds. Thomas refers to this as "a dirty, unscrupulous business that exploited humans and Earth alike".

Fashion is one of our biggest global polluters, "responsible for nearly 20 per cent of all industrial pollution annually" and "10 per cent of the carbon emissions in our air". Deep down, we knew our clothes often were made by desperate people in unthinkably dire situations; how could we forget the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh that took the lives of more than a thousand factory workers? Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic has made the human cost of fast fashion devastatingly clear. Crowded, unhygienic environments coupled with exploitative employment and a shady supply chain left brands with no accountability and employees with no pay.

According to Thomas, we buy five times more clothes than the previous generation, with the average garment being worn only seven times before being thrown on the scrap heap. There's no escaping the pangs of guilt that many of us experience with these suspiciously cheap garments. However, there is also no denying that slow fashion can be prohibitively expensive.

Should caring about the environment be a privilege afforded only to the haves, with the blame being placed squarely on the have-nots? And should the onus fall on the consumer to fix the deep-seated problems in the fashion industry or should corporations take responsibility for their exploitative behaviour?

THE SEASON OF DISCONTENT

"At a certain level, most of us were forced to make what the industry told us to make, but it's already proven that the industry is broken. We will now concentrate more on making what we want to make and how we want to make it."

Sonia Carrasco, Fashion Designer and Brand Owner

There are calls for reform, with designer Dries Van Noten urging leading industry figures to sign an open letter setting out some demands. Van Noten wants to reduce the number of runway shows, and the preposterous volume of clothing produced, and sell collections in real-time. That is: bikinis in S/S and coats in A/W. Have you ever been shopping for summer staples, only to find all the season's rejects already relegated to the sales rack? Fashion moves at its own pace darling, a pace at odds with customers' needs. Van Noten says this is about making collections "more environmentally and socially sustainable" with a move towards sustainability throughout the supply chain with less product, less waste and less travel.

Not that Chanel is paying attention, taking customers and press to Capri for its Cruise 2021 pre-collection in June, in the midst of the COVID pandemic. The French fashion house is resolutely old guard, announcing it will stick to six shows: two ready-to-wear, two couture, as well as cruise and Métiers d'Art. Chanel is not alone, with Dior also showcasing its cruise collection physically in Southern Italy.

In response to COVID-19, the British Fashion Council and the Council of Fashion Designers of America released a joint statement, echoing many of Van Noten's concerns. It urges brands, designers and retailers to slow down, with appeals for changes that will benefit customers, improve the wellbeing of the industry and have a positive effect on the environment.

FASHION IN THE TIME OF PANDEMIC

"I try to ask myself what is the meaning of my actions. It's a vital and urgent questioning for me, which demands a careful pause and a delicate listening."

Alessandro Michele, Creative Director of Gucci

The big players in luxury fashion produce between six and eight collections per year, spending an eye-watering amount of money on each show. But is fashion week, with all its excesses and spectacles, gone for good?

The pandemic has led to a cascade of reflection and introspection, and fashion's big players were not unaffected. Saint Laurent announced plans to '"take control of its pace and reshape its schedule". Alessandro Michele has reduced the number of Gucci shows from five to two, nixing both seasons and gender. He writes: "I will abandon the worn-out ritual of seasonalities and shows to regain a new cadence, closer to my expressive call. We will meet just twice a year, to share the chapters of a new story".

After the cancelling of June's men's fashion week in Paris, Louis Vuitton disregarded both the industry's European home-base and its calendar, taking its latest men's show to Shanghai, a big change that signals a significant move towards a consumer-first approach. Which makes perfect sense with shoppers from Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America accounting for the bulk of luxury sales. Is it time to admit that Eurocentric fashion shows are so last season?

Many brands have gone "phygital", which is the somewhat awkward portmanteau describing the hybrid of physical space and digital technologies. With Shanghai and Moscow both fully embracing digital for their fashion weeks in March and April, and Helsinki adopting a purely digital format with innovations such as 3D shows. If more fashion houses go off-piste with localised, digitally amplified events, this could be the death knell for fashion week as we know it.

Another big IRL fashion event on the calendar is the Met Gala, an annual fundraising gala for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute in New York City, and the most-watched fashion/society event of the year. It's usually an occasion for a (very) select few to dress-up in response to the year's theme, in a grand display of fashion as art, with the results ranging from the sublime to the ludicrous. This year it was postponed.

The show must go on, as they say, and it was a group of Gen-Z internet kids known as High Fashion Twitter (or 'hf twitter', because they're too cool for CAPS) hosting the biggest fashion party of the year. On May 4th, instead of the exclusive, highly branded, extremely profitable, marketing opportunity the Met Gala has become, hf twitter brought us an inclusive online celebration of self-expression and diversity. Whether dressing themselves, collaging or using other visual means, the guests shared their 'looks' on Twitter with the hashtag #HFMetGala2020, taking fashion out of the hands of the establishment, if only for a day.

High Fashion Twitter is a loosely structured mix of fashion fans and aficionados, who share inspiration and knowledge while being vocal about industry issues such as representation, sustainability and accountability. And for the event, they purposefully excluded any brands they deemed problematic, such as those known for cultural appropriation.

FASHION AND SOCIETY

"I understand that, for many, the purpose of a fashion magazine is about escapism, about providing beautiful images of beautiful people in beautiful clothes […] But there are moments when this feels weird. And this is one of those moments."

Emanuele Farneti, editor-in-chief of Vogue Italia

The effects of a global disaster of this magnitude amplified many social justice issues, notably resulting in the backlash over tone-deaf comments from fashion brands about the Black Lives Matter Movement, or their conspicuous, deafening silence. There was nowhere for the industry to hide.

While taking any political stance wasn't de rigueur for most major fashion houses, it's now not only accepted but expected to be in touch with issues facing the wider community. In fact, for some, this out-of-touchness is seen as impossibly callous in a world confronted by human tragedy and economic devastation.

There have been attempts to meet the moment, with efforts such as Vogue's new web series "Good Morning Vogue", fashion's self-proclaimed "wake up call". If the last decade has shifted the discourse around issues such as racism and climate change, then the global pandemic has accelerated it.

FASHION GOING FORWARD

"Through the creation of less product, with higher levels of creativity and quality, products will be valued and their shelf life will increase. The focus on creativity and quality of products, reduction in travel and focus on sustainability […] will increase the consumer's respect and ultimately their greater enjoyment in the products that we create."

The British Fashion Council

Driven by a new generation of socially and environmentally conscious consumers who care where the things they buy come from and where they'll end up, brands have upped their sustainability game. And with the threat of this pandemic acting as a call to action for the fashion industry to slow down and scale down before we find our selves facing a much bigger existential threat.

COVID-19 has caused a significant shift in the mindsets of both brand and consumer, teaching us all to slow down and reset. And should this pass, the things we learnt to value, such as our health, our freedom and hopefully our planet, may eclipse our desire for any conveyor belt of trends.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Power of Pantone

Yves Klein described his blue monochrome paintings as an "open window to freedom." Artist Anish Kapoor described Vantablack, the darkest substance known, as a black so black "you could disappear into it". Artist or not, how we view colour isn't merely a matter of taste; it's deep-seated in our associations, ideals and worldview.

Since 2007, Pantone, a company recognised as a global authority on colour, has been releasing a 'Colour of the Year'. A shade regarded as a "snapshot of what we see taking place in our global culture that serves as an expression of a mood and an attitude."

With names like Radiant Orchid that "blooms with confidence and magical warmth", Blue Iris, (dependable, soul-searching), Tangerine Tango (Vivacious and friendly), the colours are surely about more than trend forecasting.

Some saw serenity and Rose Quartz; released together in the same year and described as "an inherent balance between the warm and the cool" as a commentary on gender equality, and 2018's "dramatically provocative and thoughtful" purple shade, Ultra Violet, was a mixing of "two shades that are seemingly diametrically opposed".

Sometimes Pantone doesn't decide. A colour chooses itself and comes to represent a whole generation. Millennial Pink. No one is entirely sure where it came from or what the exact shade even is, but what they do know is that it sells. It's advertising pixie dust for all genders, selling everything from Insta-ready interiors to men's grooming packaging.

The most common version of Millennial Pink is very similar to a shade called Baker-Miller Pink, a colour created by a biosocial researcher in the late 70s for an experiment to see if using it to paint prison cell walls would calm down the prisoners. The results indicated that it lowered blood pressure and aggressive behaviour. Newer research, however, suggests that the effects of colour on behaviour are marginal. The Executive Director of the Pantone Colour Institute, Leatrice Eiseman, disagrees: "Colour is an equalising lens through which we experience our natural and digital realities." So, what's our lens this year?

This year Pantone's chosen colour is Living Coral, "An animating and life-affirming coral hue with a golden undertone that energises and enlivens with a softer edge." In reference to this year's selection "the onslaught of digital technology and social media increasingly embedding into daily life" was explicitly mentioned as a factor. Living Coral is prescribed as an antidote to mindless scrolling: A life-affirming, decidedly IRL shade.

Hopefully, the irony is not lost on them when everything from Living Coral cookware to Living Coral coffins start flooding the internet.

Apparently adept at reading the zeitgeist, Pantone's Vice President says "We want to play. We want to be uplifted." But what if we don't?

Sometimes to colour something is to change it, to distort it. And while Pantone is often obliquely alluding to the anxiety of the times, it is simultaneously colouring the year with optimistic nonsense. In an increasingly polarised world where the 'Other' is so often dehumanised and portrayed as a threat, maybe it's time we should be looking inwards into our darkest depths.

Or maybe it's time we all just disappear.

I hereby crown Vantablack the 2020 colour of the year.

0 notes

Text

Tim’s Vermeer (a film review)

In a project spanning five years, Texan video engineer Tim Jenison tries to replicate one of Dutch painter Vermeer's bafflingly photorealistic 17th-century paintings, enlisting the help of his friends, magicians Penn and Teller, to document the painstaking project. The resulting documentary not only demonstrates an inventor's singular obsession but examines the intersection of technology, reflecting on what really makes an artist.

The controversial idea that Vermeer might have used technological tools in his work is not a new one in art academia. The hyperrealistic quality of his paintings lead to years of speculation that he may have used a camera obscura in his work. Jenison goes even further, claiming that Vermeer was a kind of proto photographer, using a combination of mirror and camera obscura, that would almost guarantee an exact replica. There are gradations of colour and shades in Vermeer's paintings that the human eye simply cannot perceive, and Jenison, who claims to have never painted in his life, sets out to prove this.

The documentary follows Jenison in his long quest to reproduce Vermeer's 'The Music Lesson', going to the lengths of constructing a life-size replica of the room. As well as making an excellent case for Jenison's hypothesis, the film raises the questions: is an artist who uses the technology at his disposal a fraud? Can anyone with patience and perseverance create an artistic masterpiece?

Getting a glimpse of an inventor's relentless curiosity is always a joy, but this film also leaves you questioning the image of the great masters as rarefied creatures of inspiration.

0 notes

Text

Poet of Positivity

I don't remember how I came across the poetry of self-styled 'internet poet' Steve Roggenbuck, but I remember how I felt; euphoric, giddy and greedy for more. I spent the next few days chain-watching his youtube videos and hassling anyone who'd listen to watch them too. His poetry is a raw, unmediated blend of puerile humour, internet vernacular and surprising flashes of wisdom so beautiful, your heart grows a size. In his films, he's often outside in woods and fields shouting over Dubstep as if he were an evangelist at the church of YOLO. If that sounds like it shouldn't work, that's because it probably shouldn't.

Roggenbuck's most popular video, Make Something Beautiful Before You Are Dead, is filmed on his phone, and is mostly footage of him running around outdoors, parodying badly made video blogs and shouting inspirational soundbites about hugs and rain. Between the infectious chaos and sermonising, something remarkable happens; it works. You want to go outside and stand in the rain, you want to hug somebody, you want to make something beautiful before you are dead. YOLO is a recurring theme in what he calls his Carpe Diem poems. Roggenbuck also writes love poems that are hilarious, unexpected and oddly sweet. Love poems with verses that wouldn't be out of place among some big names. Verses such as "i sing into your mouth pretending you are dead / it sounds like you are the ocean / i hold your mouth like a cup / it sounds like you are full of what the sky is full of".

A native child of the digital age, Roggenbuck uses social media not only as a publicising tool, but as a vehicle to create his work, and a recurring motif in it; referencing selfies, Pinterest, and Snapchat in his poems. He sees social media as a means to reach more people where they are, he want “the opportunity to be in people's lives every day." He is confident that his personal hero, poet Walt Whitman, would have loved Twitter.

If you think that poetry should be exclusive, elitist and full of complex allusions, this definitely won't be for you. Roggenbuck's poetry is staunchly democratic, chaotic, and often puerile, with frequent dick jokes and references to Justin Beiber. His written work is also full of deliberate grammatical errors and misspellings, giving the impression that, as if overcome, he's typing too fast to care- but mostly it comes across as a sort of rebellion against the rarefied status of poetry. In this light, his work can be seen as quite radical, railing against the stuffy old-guard of the poetry establishment. Roggenbuck has been described as the first true 21st-century poet, but not everyone is convinced he’s a poet at all. On the back of his latest book If U Don't Love the Moon Your an Ass Hole- he acknowledged his detractors by printing harsh criticism in place of praise, such as "possibly the worst thing that has ever happened to art" and "please die".

A great self-publiciser, Roggenbuck lists Gary Vaynerchuk, a social media marketing guru, as one of his biggest inspirations. In his video poem An Internet Bard at Last, he says "I'm interested in marketing, but I'm mostly interested in marketing the moon." A part of me worries I'm a sucker, falling for a charlatan, a marketeer approximating poetry. But I ask myself, even if he is just a savvy marketeer, with such an uplifting message, can that really be bad?

Roggenbuck identifies not only as a poet but as an activist, his plan: to 'boost the world'. He intends to do this by making positivity and dedication to improving the lives of others "cool". In an interview with Impose magazine, he says "to me, spending your time on direct efforts to help others and end oppression is one of the coolest things you can do."

Exposing himself with such sincerity and positivity seems like a radical act in a jaded world, and also makes it inevitable Roggenbuck will have his detractors. But I find his earnest intensity irresistible, his love poems sweet and his vulgarity funny. Most importantly, he makes me want to shake off my cynicism, run shouting through the woods and boost the world.

0 notes

Text

Melancholy and the Tortured Artist

Baudelaire couldn't conceive of beauty without melancholy, and Flaubert believed that artists should have a "religion of despair." The literary and artistic glorification of melancholy has been going on for millennia. Why are we so drawn to misery? It may have all started with the Aristotelian question, "why is it that all those who have become eminent in philosophy or politics or poetry or the arts are clearly melancholics?" linking genius and despair in our collective consciousness forever. But is there a real link between suffering and creativity? And if so, what came first, misery or the art?

Melancholy comes from the Greek melan- 'black' & kholē' bile,' an excess of which was thought to cause depression. The Anatomy of Melancholy, a huge meandering tome by 17th-century scholar Robert Burton, gives an account of every idea about melancholy by every historical or contemporary thinker ever, including Burton himself. To provide a sense of its scope, the book's full title is 'The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up.' At 1400 pages, the book is as long as the title might hint, but far funnier than the gloomy subject matter suggests.

Burton noted the ambivalence of melancholy when he referred to it not merely as sadness, but as a 'pleasurable sadness'. Marsilio Ficino, a 15th-century Italian humanist, believed that melancholy was a sign of more profound thought and feeling. This had a significant influence on other Renaissance thinkers, resulting in the 17th-century cult of melancholy, the 19th-century and Dark Romantics' fixation with unrequited love. And Morrisey.

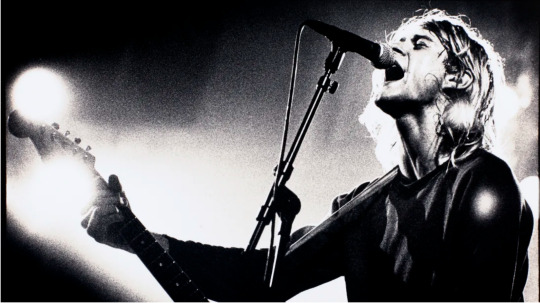

Melancholy became depression, and excess bile, a chemical imbalance. But the glorification persisted. I experienced this through Generation X angst in the nineties, when melancholy became Mellon Collie,* and the 27 club was so exclusive it was worth dying to get into. My adolescent heroes met somewhere at the intersection of misery and self-destruction. I can still recite from memory 'Alone', the poem by Edgar Allen Poe about someone so unique in their sorrow and alienation they almost certainly died alone (this obviously resonated with me as a middle schooler.)

Teen angst aside, is there any truth in the association of art with suffering and madness? My teen hero Poe seems to be suggesting there is: "Men have called me mad; but the question is not yet settled, whether madness is or is not the loftiest intelligence— whether much that is glorious— whether all that is profound— does not spring from disease of thought— from moods of mind exalted at the expense of the general intellect." Or have Poe and I both just bought into a myth, some kind of relic from antiquity?

There has been much scientific research that indicates that this isn't the case and that there really is a correlational between genius and creativity, and psychopathology. The link is especially pronounced with mood disorders such as depression and bipolar. A 2010 study tested the IQ of 700,000 Swedish teenagers then came back a decade later to test their levels of mental illness. The results showed that the most intelligent teens were four times as likely to develop bipolar disorder in adulthood. So the genius link stands up to scrutiny. There is also evidence that the link is even more pronounced with artistic brilliance, as opposed to regular garden variety genius.

Professor of psychology at the University of California, DK Simonton, claims that "creativity shares certain cognitive and dispositional traits with specific symptoms [of psychopathology] and that the degree of that commonality is contingent on the level and type of creativity that an individual displays". Creativity requires certain characteristics, like openness to chance, exploring the unconventional, atypical thinking and non-conformity. Simonton refers to this as the 'creativity cluster.' Some indicators of mental illness correlate with the attributes in this cluster, so creative people will often show symptoms associated with mental illness, and the more creative you are, the more pronounced the symptoms. Some types of creativity depend more strongly on the cluster, for example, scientific creativity tends to be more formal and constrained than artistic creativity, so the creativity cluster will be more pronounced in artists than in scientists, making the mad artist a little madder than the mad scientist.

This link seems to extend past pathological mood to disorders, to ordinary transient moods. In 'The dark side of creativity: biological vulnerability and negative emotions lead to greater artistic creativity' a study in which participants' baseline levels of dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEAS), a hormone associated with managing stress and depression, were tested. They were instructed to make a short speech about their dream job. Their speeches were greeted by negative, positive or neutral nonverbal feedback. The participants were then required to each make a collage, which was subsequently judged by a panel of artists. The ones made by participants who had experienced rejection were deemed more creative, and these results were intensified in those were a lower baseline of DHEAS, suggesting that they are most sensitive to emotional triggers.

According to Joe Forgas, a social psychologist at the University of New South Wales, sadness promotes "information-processing strategies best suited to dealing with more-demanding situations." Forgas influences his subjects into feeling sad, then tests their cognition. He demonstrates that subjects who are melancholy exhibit improved cognition and more attention to detail. This heightened focus and presence may be why people experience melancholy as a more aesthetic emotion. They're simply more present. Susan Sontag makes a distinction between melancholy and clinical depression, describing melancholy as depression "minus its charms," (perhaps because she knew firsthand that nothing is charming about the debilitating illness) marking melancholy as an aesthetic experience, separate from depression.

There seem to be many of legitimate reasons the glorification of the tortured artist has endured. A romantic, harmless face of depression, aspirational misery. The tortured genius, suffering = art. It's more intellectual than physical, existential than medical. There is no black bile, and if death comes, it comes pretty and quick. Suffering is not only romantic but sublime, and a fair price to pay for art. There’s something disturbing about romanticising the Cobains, the Plaths and Von Goghs. As compelling as it is, it seems strangely cavalier. I wonder if they would have not given up all that brilliance for peace of mind. Doesn't glorifying their suffering somehow reduce them to collateral damage in the quest for the sublime?

The link between melancholy/depression/negative emotion and creativity/art/genius has been documented by history and demonstrated by science. But I reject Baudelaire's idea that melancholy is essential to beauty. That suffering is on a higher plane. The notion that suffering is intrinsically sublime.

It makes me sad that art ought to be sad, so I'm rebelling against melancholy—no more suffering for art. Bliss isn't ignorance. Playfulness isn't trivial. Let's elevate joyful creativity, stop believing art only comes in heartbreak, see happiness as transcendent, and create from a place of genuine rapture.

Now, I'm off to make sad art about how sad I am that art has to be sad.

*Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness was an album by The Smashing Pumpkins, 1995

0 notes