Text

Pier 45 Party for the End of the World

In responding towards the critical reevaluation of the subconscious and hierarchical precedent of mobility within architectural discourse, studio Roy primarily focused on transcalar representational techniques. Immediately, I was drawn towards stratigraphy and the residual embedded knowledge that is seemingly rendered lost under the tumultuous current of history. Within an urban context, I became interested in the motifs which the public use to understand this loss and its surrounding sociopolitical, such as within the process of graffiti.

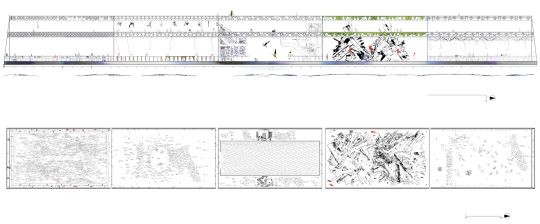

When turning towards our site of Pier 45, I became enthralled by the rich yet hidden history of the Meatpacking District. I researched the infrastructural networks and history which made the area suitable for the processing of meat; this was compounded by the elusive BDSM/LGBT subculture which was prominent in the area around the turn of the century. I then subverted these infrastructures and staged a party with five different scenes, or “happenings.” Each happening receives its individual section and plan. From left-to-right: Meat Dinner; Yoga Party; Dive Party; Salvedge Hiking; and an Animal Farm Entrance.

0 notes

Text

The Dale Earnhardt Memorial Super Speedway

My inquiry into NASCAR-culture and the design of oval-track racing began with a novel interest in the Dale Earnhardt 2001 Car Crash as my initial form of damage control. I took Dale’s case as an avenue into analyzing the intermingling between car and speed culture in relation to American media antics.

Dale Earndhardt’s 2001 crash, when analyzed beyond its immediate impact, could be considered a textbook case of spectacle. Earndhardt, number 3, was already extremely popular at the time of the race, and his instant death only compounded this status, making him reach legendary status in NASCAR history–he is still beloved by fans, both in memory and in material artifacts.

The Daytona 500 is the ultimate competition and broadcast for NASCAR drivers and fanatics–it is their superbowl, so to speak. This was compounded by the fact that the 2001 Daytona 500 marked the first Cup Series race under NASCAR's new centralized television contracts, which shifted responsibility for NASCAR's media rights from the track owners to NASCAR itself.

In analyzing the crash in-itself through autopsy and traffic-collision reports, I realized that the crash could only be understood fruitfully within a system of components–not one single thing “killed” Dale. My drawings then worked towards unraveling these facts. What differentiates his crash from Schrader’s (no. 36, who crashed along with Dale but left the scene basically unharmed) is plentiful, but I mainly focused on the particular velocities and geometries, which created such an arc to enact a particularly brutal impact. I carry this language of forensic and geometrical analysis throughout my design.

The tracks (including Daytona) boast quite an extensive and impressive amount of engineering ingenuity to make racing safer, especially after Dale’s death, which sparked a movement towards safety in NASCAR (which, of note, Dale himself demeaned and constituted as the reason that NASCAR was heading on a downwards path). For example, restrictor plates are enforced upon the stock-cars so that they may not reach the risk of their top-speed.

NASCAR, as many other people comment, has found a way to make the car-crash both safe and beautiful–plenty of crashes have occurred since Dale’s crash in NASCAR, but none of them have been fatal. This is mainly due to the aforementioned engineering ingenuity spawning at NASCAR-tracks, for example, the SAFER-Barrier which enwraps the course of a track so that there is a softer impact, as compared to crashing straight into concrete.

Inspired by this, I initially began by subverting this safer-barrier design to create a seating situation on-top of these barriers to allow viewers an intensely close view of the track while simultaneously maintaining a high amount of safety.

From thereforth, the objective of my final project became clear: to reimagine the in-situ engineering artifacts currently being deployed at oval-track stadiums and push them to their limits to create newfound perspectives for people to experience the races. To agitate the boundary between risk and safety while paying respect to the culture and ingenuity of NASCAR.

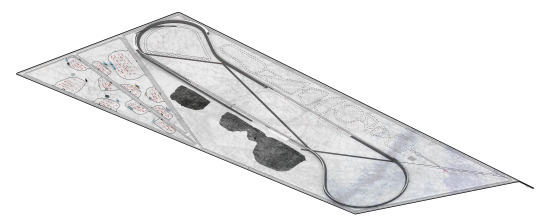

I decided upon the site of the Bonneville Salt Flats (Western Utah); both for its historical precedent of landspeed records but also because salt is particularly enthralling for speed because of its frictionary properties. My design is kept incredibly long and short in order to keep the landscape views in-tact.

You enter the stadium through an exit-ramp heading Westbound on the Dwight Eisenhower Highway, just a mile or two before Wendover. This ramp is banked and an autobahn, allowing people to experience oval-track conditions for a mile-long stretch until they reach the track itself. Car circulation is handled by roads which are the offset tangential angles of the track’s banked curves.

0 notes

Text

The Gothic Flatline and Infrastructure Studies

Mario Ramirez-Arrazola

Fall, 2021

Michael Fisch in his book An Anthropology of the Machine: Tokyo's Commuter Train Network outlines an almost surreal picture of the Tokyo metro, which at first glance, seems like a monotonous beast which only serves a utilitarian purpose. This surreal picture constantly includes historical examples of bodily violence and death in relation to riding the train, as well as examples of “living” which calls to reference the common saying that “you die a little bit each day.” In reference to the Tokyo commuter train infrastructure, this death paradigm is not hard to see. The train itself has somewhat of a suicide culture; there are corporate a in line to answer for train suicide; some shuttles are divided by gender in order to help women feel safer from sexual assault by male riders; some news outlets have changed their rhetorical techniques whenever reporting on train suicide; riders have the system “etched” into their physiology, pulsing awake from a deep slumber whenever their exit arrives; there is an ongoing narrative that overworked salarymen are the typical train suicide demographic—the list goes on. For other infrastructural systems, this almost phantasmic interaction between the infrastructure and the life/death paradigm is more hidden, though nevertheless present. The leading question of this paper then becomes: why do humans and non-humans in their interaction with infrastructural systems speak about their experience in terms of death? Or, why can their interactions be framed so vividly in their implications of a more nuanced life/death distinction? The late Mark Fisher in his 1999 dissertation Flatline Constructs: Gothic Materialism and Cybernetic Theory-Fiction theoretically lays out an effective system for this question to be analyzed—Gothic Materialism. Though Fisher definitely expands beyond the first principle of Gothic Materialism, the Gothic flatline, (which we will be focusing on exclusively in this paper) is the most salient to this study, as well as the most important to Gothic Materialism.

My analysis is informed by previous research that tries to extend agency in infrastructure studies beyond humans, or that shows agents coming interacting deeper with the life/death distinction, (the Gothic flatline) but I argue in this piece that our very conceptions of those same agencies will need to be extended to encompass a more nuanced divide between life and death.3 This is because death, as Fisher illuminates in his conversation on the Gothic flatline, is not a binary condition. Rather, agents occupy a space where they constantly flow through the realm of life and death; death is always coexisting with life and one state does not take prowess over the other. Fisher draws a lot of inspiration surrounding the life and death divide from Xavier Bichat. Fisher is unique however in that he provides the necessary and salient theory to bridge Bichat’s theories into a modern/postmodern landscape, and in our case, modern infrastructural systems. I aim to provide a salient historical case study that qualifies the use of a Gothic Materialist methodology within STS. The particular case I will be analyzing through Gothic Materialism is the Tokyo metro system, with a particular look at the acts of bodily violence which happen within the context of the train experience, both inside and outside of the shuttles. I will also be drawing in the various works (those that made me initially interested in this question) which have tried to extend agency in infrastructure studies beyond humans but also those studies which illuminate interesting examples of agents flowing through the life and death divide in their interaction with infrastructure.

In a way, this paper and Fisher’s dissertation can be seen as an applied and theoretical elaboration of chapter one of Xavier Bichat’s Physiological Researches on Life and Death, originally published 1800. Bichat was not generally interested in providing metaphysical details of the body and physiological nuances, rather he wanted to provide research that resonated with the standardized scientific method at his time. Nevertheless, many of his statements were often prolific. There are the two general statements which are most salient to this study and his overall influence, one being his definition of life as a total history of the specific bodies’ resistance against death, translated from French into English: “Such is the mode of existence of living bodies that everything surrounding them tends to destroy them.”5 The second point is Bichat’s division between organic life and animal life. Organic life can be seen as the bodily systems which act without direct control: heart, lungs, kidney, liver, etc. The animal life can be seen as bodily systems which act in accordance with the body's nervous systems and ambitions: limbs, eyes, ears, nose, fingers, etc. The animal life can operate without the heart, which to Bichat was the central organism behind organic life.6 In Fisher’s dissertation he expands on Bichat’s two main statements through Foucault and Deleuze—Deleuze’s interpretation of Bichat will be of more use to this study, but it will still be useful to expand on Foucault’s take. Bichat’s first statement can be seen fruitfully in Foucault’s The Birth of the Clinic, particularly in Foucault’s notion of life as the origin of disease itself, and of death as not a singular point or destiny but rather as a continuing battle against illness and disease in the patient's life, Fisher elaborates: “The Foucault of The Birth of the Clinic encountered the flatline when reconstructing Bichat’s version of death. Rather than being a destiny waiting for the organism at its termination, “death” is the real process the organic-vital is parasitic upon from the start; it is an event, aeonically multiple rather than chronically punctual.”

Fisher then elaborates on Delezue’s take on Bichat’s second statement: “Bichat put forward what’s probably the first general modern conception of death, presenting it as violent, plural, and coextensive with life. Instead of taking it, like classical thinkers, as a point, he takes it as a line that we’re constantly confronting, and cross only at the point where it ends. That’s what it means to confront the line Outside.” Deleuze took up Bichat’s divide between organic and animal life seriously in his lectures. Sometimes Bichat’s statements were so profound that they dumbfounded Deleuze, to the point where he couldn’t make a clear interpretation. Deleuze discussed and struggled through Bichat during some of his lectures/seminars, particularly the lectures on the dates of: March 25, 1986, March 18, 1986, and November 26, 1985. Deleuze believed Bichat to be a modern (as opposed to classical) thinker despite his time of operation because of his incredibly progressive theories surrounding life and death; it is intriguing to Deleuze what Bichat meant and what the implications for his new concepts are on four points. On one point, that death is coexistent to life and that death is not a single point or break with life, this notion is the break away from classical notions of death for Deleuze; second, that death encroaches upon life in a swarm-like manner, affecting different parts of the body at different points of your life time;10 third, the division of life between organic and animal; and fourth, the division of death between natural and violent death. Deleuze’s interpretation of these divisions involve the definition of organic life as the continuous half that you inhibit yourself within a particular place, this is more alongside the conceptions of a classic death, and organic life is not particular to humans but also includes animals and plants. On the other half, at the center of the animal life is the nervous system—this animal life is intermittent because of sleep, sleep is multiple, traversal, and particular, we return to organic life when we wake from these particular sleeps. The distinction between natural and violent life is what confuses Deleuze the most, but nevertheless something he definitely agrees with. Death from old age would be considered a natural death, and to Bichat this is the death most common among animals. This confused Deleuze (for which he makes sure not to blame Bichat) because it seems evident that animals are constantly killed by humans and other animals. Violent death, on the other hand, is much more understandable to Deleuze—violent death is society as a whole. Society wears down egregiously on our animal lives, causing violent deaths.

Here it is nice to finally put Bichat’s idea into practice, this violent death is not a single point, rather it’s different deaths that happen at different times of your life because of interaction with Society: “At any rate, he’s not wrong, either… he didn’t know it, himself, but uh… assault, social assault, is terrible, people who talk too much… people who talk too much, that’s an assault. Uh… [?] Neon lights, neon lights… Bichat didn’t know about them, but neon lights are an ocular assault all the same. TV is an assault, a pure assault. You’ll say… well… yes, anyway. It’s true that society wears on my animal life. He won’t portray it as a supplementary sphere of life; Bichat is too clever for that—he says that society is the acceleration of all the functions of animal life. But animal life is, on the contrary, a life which really needs intermittence, really needs rest, really needs its particular sleeps. But we, as we know, have one big sleep, and yet, unhealthy, we no longer have these particular sleeps. [...] Then, as our animal life is so worn out by such high-tempo rhythm, the our [sic] form of death tends more and more to become violent.

Given all of this context on Bichat, Foucault, and Deleuze, we can now move firmly onto Fisher’s own methodology and elaborations of Bichat’s theories which illuminate the Gothic flatline, which to Fisher is: “a plane where it is no longer possible to differentiate the animate from the inanimate and where to have agency is not necessarily to be alive.” To fully understand what the Gothic flatline is Fisher believes that we will need Gothic Materialism as a methodological approach. Fisher is aware that joining the Gothic—what is originally thought of as ethereal, otherworldly, spiritual, supernatural—with Materialism might seem to be contradictory, but this is exactly Fisher’s aim, to instead be concerned with a: “plane that cuts across the distinction between living and nonliving, animate and inanimate. It is this anorganic continuum, it will be maintained, that is the province of the Gothic.”14 Fisher gives a great overview into why cybernetics is so particularly telling of our modern times and also why cybernetics aims to provoke the life/death paradigm, he terms this cybernetic realism. We will not go into this particular section but it is salient to this discussion as a whole. Fisher designates the first principle (arguably the most important principle) of Gothic Materialism to be that: “The Gothic designates a flatline”15 as a reference to the sociotechnical usage of flatline (what is said when the electroencephalogram reads no activity, indicating brain death). Additionally, to Fisher the flatline is actually where everything occurs: “the Other Side, behind or beyond the screens (of subjectivity), the site of primary process where identity is produced (and dismantled)... It delineates not a line of death, but a continuum enfolding, but ultimately going beyond, both death and life.”16 Fisher goes at length to explain this first clause, but I believe that there should be careful attention to how Fisher illustrates this flatline on its path, borrowing from a passage in A Thousand Plateaus: “the flatline designates an immanentizing line,” a “streamlining, spiralling, zigzagging, snaking, feverish line of variation… a line of variable direction that describes no contour and delimits no form…”

This recalls another methodological technique already being implemented in infrastructure studies (although not in the same scope)—and as is most showing in The Undersea Network by Nicole Starosielski—called transmission narratives. A direct definition of transmission narratives is gave, as well as how it contrasts with nodal narratives: “Nodal narratives use specific locations in the network to track the intersection of different flows; transmission narratives follow a signal or person across an infrastructure system, tracking movement between interlinked nodes.” Starosielski, in their analysis of underground transoceanic communication pipelines, aims to disturb the invisible nature of our concepts surrounding telecommunication technologies by “surfacing” the pipelines (a good example of an unsurfaced infrastructure being the internet “cloud”), as well as using transmission narratives to not merely analyze the start and end nodes of these communication infrastructures, but rather their progressions along these plots, the travel between these nodes, and the muddled context behind their implementation: “Although narratives of transmission follow cable technologies, they almost always do so to reflect on the human dimensions and embodied experiences of these systems” In tracing transmissions and paths along these lines of communication instead of only focusing on the end-nodes where “connection” really happens, Starosielski puts to center the agents, environment, and general history that goes into these undersea communication lines. This reflects the plot of the flatline as envisioned by Fisher—a line definitely not straightforward. The transmissional line bounces around points in time, zigzags around the environment, and is generally chaotic in scope. We will need to envision actors and their interaction with infrastructure in this same manner, as moving along the line of life and death in a fashion that is not “straightforward.” According to Fisher, this spiraling plot emerges from a Spinozistic mindset, the: “refusal to distinguish nature from culture.” The blurring between living and dead, the animate and inanimate, the natural and unnatural, things and beings, and so on. It is my argument that when we study humans and non-humans and their interactions with infrastructural systems we must also pay attention to how their relationship between life and death is nuanced by these same interactions. This illumination is more obviously seen in some specific infrastructural systems than others, but nevertheless it is an ever present factor. Gothic Materialism is helpful when dealing with an infrastructural system that acts as a catalyst for the creation of complex psychological or physiological reflections on the user’s experience with the infrastructure in terms of their experiences with life and death. This is because Gothic Materialism allows the analyzer to devote their time away from trying to find a nexus of reason behind these muddled interactions, rather now for the analyzer all of the experiences act as an aggregate and form into a sort of rhizome which steers away from generalization.

Another great infrastructure study that utilizes transmission narratives and confronts that Gothic flatline is Max Hirsh’s “What’s missing from this picture? Using visual materials in infrastructure studies.” Hirsh confronts the propaganda-like nature of airport visual advertising with a particular focus on the Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA). Whereas those more privileged are allowed an enhanced quality-of-life experience of airport traveling in major hubs, the visual imagery which depicts these hubs does not account for the majority of “non-traditional” travelers, Hirsh states:

“What these scholars don’t tell you is that the facilities portrayed in these images typically accommodate less than a fifth of all passengers flying through major airport hubs. The infrastructure systems used by the other 80% – students, retirees, migrant laborers, low-income tourists – are largely absent from official maps, ads, and brochures; and thus remain unaccounted for in existing discussions of airport infrastructure. Yet it is precisely these non-traditional travelers who have driven the exponential increase in global air traffic over the past 30 years [...]”

Hirsh uses his own ethnographic photographic imagery of these “up-stream” check-in terminals which facilitate all of these other 80% of travelers through their airport experience; the photographs are eerie and grim. The most salient of this imagery being his storyboard of a Filipino cleaning women’s travel through Hong Kong to their home in the rural Philippines. Hirsh utilizes a comic-strip to illustrate their journey: waking up at 6:30am in their Sai Ying Pun flat which they share with five other people, traveling to an unconventional airbus stop, their first in an eight hour journey via the HKIA. Certainly a draining trip, one can only imagine the multiplicities of death which are felt by these unconventional travelers; Hirsh alludes towards these muddled experiences through the narrative he creates, which reflects the transmission narrative—he is quite literally following these people through their experiences and detailing the travel itself rather than focusing on the end or beginning nodes. Though out of scope of Hirsh’s article, it would have been interesting to see an attention to the first-hand accounts of these experiences and what feelings they evoke in the traveler in specific. The Gothic flatline arrives no matter the first-hand accounts because there is an obviously draining paradigm going on at the HKIA. A question then arises on whether or not the travelers realize this deadening routine. Maan Barua, in “Infrastructure and non-human life: A wider ontology,” speaks on a vast array of reasons why agency in infrastructure studies should be extended beyond humans, what is particularly interesting and salient in his article is the discussion on “recombinant infrastructures” and “Non-Human Life as Infrastructure,” particularly the Robo-Roach. Though evident in the title, it seems as if there is another grand narrative arising in Barua’s work—the multiplicity of lives and deaths of infrastructure itself. The vibrant infrastructural system reaches the Gothic flatline by itself because of its web-like interaction with other agents. Barua speaks on repurposed infrastructures with an interesting focus on termites. What was once thought to be barren, soulless, finished, or uninhabited, various infrastructural systems are rebirthed for their new use in possibly even more progressive ways than before. The termite repurposes built infrastructures such as railway sleepers, buildings, bridges, and pilings in a manner which lets them extend their movement and foraging capabilities; they progressively repurpose the substrate in an effort to prolong their lives. Barua does pick up on the new vitality which these infrastructures are presented with: “Termites are thus not just enmeshed or entangled in infrastructures, but enfleshed in that it is difficult to separate where one body ends and the other begins or, for that matter, where the divisions between corporeality and substrate lies.”

What is interesting here for discussion is Barua’s inclusion of the entomologist Lisa Margonelli’s notion of vitality surrounding the new life of these infrastructures: “Rhizomatic trails laid out bytermites generate a ‘sort of external memory’, leading some entomologists to argue that their structures themselves ought to be considered as living.”25 While true that this new life of the infrastructure is evident, there are deeper implications here, the first being that the infrastructure was dead to begin with, or that this new life now takes precedence over the death, a binary. There is a nodal-like narrative happening here where instead of tracing the infrastructure's constant battle between life and death in the total history of its operation, the infrastructure instead occupies a single state at a single point of time, the time when the termites started to incorporate the substrate into their livelihood. Barua, in his section on non-human life as infrastructure, speaks of societies’ attempts to turn animals, insects, and other non-human entities into infrastructure for the benefit of human motives. Barua immediately speaks on the epistemological problems that this anthropocentrism constitutes:

[...]

This anthropocentrism is most evident in the discussion of roaches turned cyborgs. RoboRoaches are “speculative infrastructures” which are made real through venture capital efforts and some are already commercially available; RoboRoaches are technologically modulated with sensory technology to enter destructed buildings and to find any potential survivors in the rubble. Barau alludes to the conversation of cockroaches being typically thought of as disgusting creatures but now being turned into synthetic and futuristic beings, almost miniature superheroes if they do end up finding a survivor; colloquial discussion should be more than enough here to elaborate on the implications of these RoboRoaches. First off, there is a constant violent war against cockroaches as instigated by humans—cockroaches are disgusting, unsanitary, vile, hideous, creepy, and the list goes on—one does not think twice about instantly squashing a bug to the greatest and last of its deaths when encountered. There are microeconomies based on the death of these small insects, whether it be the professional exterminator or a can of Raid bought from a local store. There is no soul to the roach, it is not “alive,” this is why it’s okay to immediately terminate them—or so was thought. I am not saying that we should start taking in cockroaches as pets, but that hopefully our conceptions of these animals, particularly their life and their death, is nuanced or rethought from their new vitality as given by their transformation into a useful infrastructure. One can only imagine the eerie or weird emotion that is evoked when something you never thought twice about murdering saves you from a certain, lonely, and claustrophobic death underneath hundreds of pounds of rubble.

Fisher further illustrates this Gothic flatline through two fictional examples, one is the German expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, in which Fisher borrows from Deleuze’s interpretation of the film as a work that makes organic, inorganic, natural, and artificial substances or entities as not able to be differentiated from one another. The second is Neuromancer where the flatline: “functions as both a verb – characters flatline (surf what, for the organism, is the border between life and death) – and a noun – some characters are Flatlines (Read Only Memory data-constructs of dead people).”27 Where infrastructure studies plays a part are the immediate connections, whatever your particular infrastructure of study, to how the system navigates this anorganic continuum, or this Gothic flatline. This navigation may be initially hidden or invisible within the system, or in other systems it may be incredibly apparent; all systems are subject to a spot within the Gothic flatline because of the system’s interaction with entities, both living and dead. Some systems may be seen as able to be analyzed by Gothic Materialism in either an intense or minimal manner, while others may be encapsulated by it entirely and act as something like Flatline Infrastructures (just as some characters in Neuromancer are referred to as Flatlines). This implies that certain infrastructures are incredibly testing of the life and death distinction. I believe that the Tokyo metro system, especially as mechanically analyzed by Michael Fisch, is the premier example of a Flatline Infrastructure.

What is most proper in this flatline analysis is not to impose the theories laid out so far in a strict or rigid fashion in their real world application, both because the general idea of the flatline is enough for the analysis (death as a multiplicity) but also because ethnographic research is most important and is what will serve as the empirical evidence which qualifies the use of Gothic Materialism. I believe the most pertinent thing then is to introduce real world accounts of what Tokyo metro culture is like. The riders will show for us themselves what the experience of riding on the train is like, we will let them speak for themselves without enforcing anything upon them, but their accounts will also illuminate their position within the Gothic flatline. One of the first accounts that Fisch gives is from a Tokyo commuter (who is both a paralegal and a law student) on the physically violent experience of riding on a packed train, but Fisch also extends his account into a detailing on the inescapable fashion of these packed train rides, “You are packed into the train so tight that you feel as if your internal organs are going to be crushed. By the time I arrive at work, I’m exhausted and too tired to do anything. I would do anything not to have to ride the packed train but there is no choice [shōga nai].” Here the Tokyo commuter feels literally suffocated, crushed, and feels as if their organs are crushed or in the process of being killed; they become somewhat Zombified by the time they arrive at work from the train ride exhaustion. Here is another account from a website dedicated to suicide advice on how to effectively commit suicide by jumping in front of a train. Fisch eerily states that a particular suicide on the Tokyo commuter lines at 7:42am, August 19th 2004 may have taken this advice, given the saddening details of the actual event:

“If you are jumping from a platform choose a station where the express train does not stop as the chance of fatality is much lower if the train is decelerating. If you misjudge the timing you might bounce off the front of the train or jump too far and end up on the other side of the tracks. So take your time. As long as the train is within a hundred meters of the station, it is not going to be able to stop in time with the emergency brake. Also, be careful since there have been incidents in which briefcases or other items have flown back and hit someone on the platform.”

This is not only shocking to read, it also implies that these directions are needed by someone, or in the particular case of Japan, that there is somewhat of an active negative culture surrounding death by train. The precautions set up by the various companies in Tokyo to discourage train suicide are extensive, ranging from soothing train music and voices, blue filters on the train windows, mirrors and better lighting to reflect before the act, and even the legal pursuit of a debt that the victims family would have to pay if their family member committed suicide and disrupted the train flow. The entire system is operating within the flatline in this manner, riders are alive in a sense while riding the train, but their suicide or death is somewhat assumed and taken account of before the fact. This is particularly true on the commuter lines which have the Autonomous Decentralized Transport Operation Control System (ATOS) enabled. These lines (operated by the JR East Company) have a cybernetic system which regulates traffic and accounts for disruption to the flow in an automatic fashion. Disruption, of which is commonly suicide, to these ATOS-enabled lines becomes the norm, as Fisch states: “ATOS thinks of the gap as a necessary condition of emergence. It does so by inverting the logic of centralized traffic control, shifting emphasis from controlling the principal daiya to managing the emergent order of the operational daiya.” Here the daiya is a traffic diagram of the train network which is broadcasted through the news, radio, television, and so on. What is even more interesting is that in the early 1990s the terminology for train suicide was sometimes differentiated as either committing suicide (tobikomi jisatsu) or an act of bodily accident (jinshin jiko). Fisch explains the differences:

[...]

It is also useful to see an actual newspaper account of a jinshin jiko: At around 8:45 a.m. on the sixth of the month a 61 -year-old man from the Tama ward of Kawasaki City was struck and killed instantly by the Kawasaki - bound train from Tachikawa City on the JR Nambu Line. As a result of the accident, 14 trains were canceled and there were delays of up to 45 minutes. According to the Tama police, the man was kneeling on the tracks. The area of the accident is 20 meters from a railroad crossing. [July 7, 1996]31 Fisch also gives a great account of the “suddenly awakening commuter,” the phenomenon that is attributed to the event of “when a commuter who appears to have fallen into a deep sleep suddenly awakens at a station and bolts from the train a split second before the doors close.” Fisch asks the question of how the commuter knows, even in this deep slumber, when their stop has approached and jolts awake (the presence of sleep in this discussion of course alludes back to Bichat’s and Deleuze’s discussions on sleep) to exit. He answers through an account of an experienced Tokyo train commuter, Mito Yuko, during their conversation over tea. Yuko states,

“The rhythm of the train is etched into the bodies of the city’s inhabitants.” And further: No matter what train line one takes in Tokyo, the pattern of acceleration and deceleration between stations is always similar. The pitch of the electric motor increases as the train rapidly accelerates when it leaves the station: eeeeewwwwwwww. . . . It levels off for a bit as the train reaches its cruising speed— pweeeeeeehhhhh— and then begins to drop as the train decelerates: dreeweeeeeeeeh, tukatoo, tukatoo. . . . [Then there’s the announcement:] “We’ve arrived at such and such station.” This pattern is the driving curve, and every commuter internalizes it from an early age. For commuters it’s a soothing sensation, lulling them to sleep the moment they sit down on the train. Because the bodily rhythm of the city’s inhabitants is in sync with this pattern, when there is a delay, even if it’s only a matter of thirty seconds, they notice it. If the delay is more than a minute, they might actually begin to feel physiological discomfort [shintai no seiriteki na fukaikan].”

This repetition and rudimentary experience becomes etched into the riders to the point where the entire process becomes somewhat of a lull that begins to wear on the animal life. The typical rider is the salaryman/salarywoman who will have almost no time to spare for anything. Fisch interviewed a Japanese bank employee by the name of Akira who details the typical train experience:

“Japanese salarymen have a fixed schedule. I leave my house every day at exactly 7:05, arrive at the station and line up at the second door of the ninth car of the 7:23 commuter express. Every day exactly the same and always with a Nikkei [Economic] newspaper under my arm. From my station until Shibuya it’s too packed to even lift my arms and hold the paper. But at Shibuya a lot of passengers get off and I have fifteen minutes to read all the important articles in the paper. There is a group of regulars I ride with but I’ve never spoken to them or exchanged a nod or greeting. A salaryman’s energy is at the lowest in the morning. It’s like “ach, back to work again and back on the packed train.”

The metro experience then becomes somewhat of a landscape where unordinary events are compounded in effect because of the intense lull that is active. Fisch has an entire section in his book where he tackles the salaryman suicide by train phenomenon, tracing the problem deeper into Japanese society and problems of representation. These are all interesting, but what seems most salient is a small conversation that Fisch had with another salaryman while in the train station. The trains had just been announced to been delayed because of a suicide, this particularly salaryman in their nonchalant reaction to the news caught Fisch’s attention and they had a conversation in which the unnamed salaryman stated:

“They do it during this time in order to elicit an appeal to their own existence, probably because they want to create annoyance. It’s always a salaryman, and it’s when they just snap, when they can’t take it anymore after failing no matter how much they try and try. There was another accident not too long ago at this station, same thing, same situation, but the guy jumped from the far end in front of the special rapid. There might be more instances [of jinshin jiko] in the summer than in the winter, I’m not sure. At first, when I came to the city from Okinawa I thought that the way people just go on as if nothing happened was cold hearted, but then I realized that they are just used to it. Now the whole schedule is disordered for the rest of the day. And after all that careful calculation. No point in trying to check it from your keitai, maybe not even until they can restart tomorrow morning.”

An overview of the Tokyo metro culture would not be complete without covering the persistent sexual assault incidents which female train riders face from male assaulters, referred to as perverts (chikan). Fisch makes clear that there is a definitive, almost culture-like, environment of heterosexual male fantasies (transgressions) which materialize on the train. Fisch states that there is many research into this problem that women face, but that he does not want to expand on the research and that he himself only has a variety of potential theories on why this environment exists in the first place; in the footnotes he also explains why he did not want to inquire about these cases of sexual assault in specific for a variety of reasons. Fisch did however receive secondhand details into the problems from women commuters, he elaborates: Female commuters with whom I spoke, including both acquaintances and friends, sometimes explained that with the intense compression of bodies in the packed train, they often felt uncertain whether the hand that brushed or grabbed them did so with intention. But it was not the uncertainty that silenced them; rather, it was the silence. As Yuko, a twenty-seven-year-old female administrator at an importing firm who commutes almost an hour each way on the Chūō Line, confided, while there were times when she suspected someone of touching her, she did not feel confident enough to carry out the required action of grabbing the groper’s hand, raising it up, and yelling “pervert.” She was afraid of the effect such an action would have in the silence of the packed train. For Yuko, riding in the women-only train car is not an option because of where it would place her on the platform at her destination and the crowds she would have to navigate to arrive at work on time.

One can then only imagine the horrors and dehumanization which women feel when riding these trains, especially when packed. Their experience is completely different than that of a male, and one wonders what emotional space they must operate within to ride the train. The Gothic flatline as theoretically laid out by Fisher is a sturdy and difficult idea to unravel, but it should be appreciated for its most novel implications of which infrastructural systems constantly encounter in their interaction with agents of all forms. Deleuze showed a worthy struggle through Bichat’s life and death paradigm, of which he applied pragmatically to societal forces: loud people, TV, neon lights, and society in general. Because infrastructure plays such a crucial part in our lives, whether invisible or visible, it should be crucially analyzed for how the system creates situations of life and death indeterminacy in agents. The Gothic flatline is most appropriate for this analysis because Fisher—though much more interested in plotting cybernetics as the premier motif to encapsulate postmodern society—was almost foretelling in identifying this particular dehumanizing nature of society. Fisher withdraws from this study in an important avenue: while he does realize that these dehumanizing affects are a process of something grander, (it is evident that he is blaming capitalism, in essence) he mainly illustrates this through the analysis of fictional works, particularly theory-fiction and cyberpunk. Though he does give an argument that qualifies the use of fiction, in these works the flatline is a zone where revolution happens—it is imminent, but still a place where progressive things can occur. The flatline in these real world infrastructure history is more nihilistic, or at least unrealized. The first step is to realize the potential of the flatline and where it is creeping upon us in our contemporary infrastructural systems—which I hope to have done adequately here—so that the Gothic flatline becomes visible and can be morphed into a mechanism which benefits the masses.

0 notes

Text

The Bullet Train of Camden

Mario Ramirez-Arrazola

March, 2022

There is a Bullet Train in the town of Camden which accelerates in speed whenever it kills someone. Its construction began after the recent war and was completed about six months ahead of schedule. There were cries and pleas from the common people for them to be allowed to work on the train; Camden turned into a proto-New York, there was no sleep, no partying, only work and the train. The people from Camden had built a train so efficient, so fast, so unruly, that they had begun to be colloquially known under the nation as the Bulleteers. The people of Camden not only built the train in its novel sensibilities, from laying the tracks down to putting together the train’s framing, but to other more advanced technicalities, such as programming the train’s route as it moved through the crowded city. The train had no traditional conductor in the main shuttle, rather the train network was controlled through a centralized surveillance system completely exterior from the actual location of the train’s operation.

The train was a resounding success in terms of raising the quality-of-life standards in Camden—riding the train was free and was mostly used for commuting to either work or school. The train was also surprising- ly safe, with the occasional junkie causing a scene, but not being widespread enough to deter riders. This was mostly because the city of Camden created a small police force, the Camden Transit Security Force (CTSF), to patrol the metro network. The train had its occasional incidents, mostly exterior, such as cars stopping in the middle of the train tracks or an indecent and illegal scene happening on the train.

It became very apparent however that something strange was happening with the train, a phenomenon that became local to the city of Camden. A train-suicide occurred about a year and twenty days ago—the first of its kind in Camden. No one thought much of it and most focused on the depressing nature of the victim’s background, a veteran of the recent war. He committed suicide shortly after leaving a mental institution by quickly jumping into the path of the Bullet Train. He gave himself enough time to set up a large white canvas behind him (almost like a flag), stood up by two poles, in such a way that the train could not have enough time to slow down to a safe speed. There was plenty of footage, as CTSF has plenty of surveillance cameras around the station, and it was almost like abstract performance art. It was quick, and what was left behind was an imprint of the man’s bloodied and splattered body upon the canvas. Shortly after there was also footage released of the man testing how far apart he needed to position the poles so that they fit perfectly within the margin of the train tracks.

There was no time, or space, to remove the remaining body parts. There was no stopping, in a way that the world didn’t stop when the man died, from the train. In fact, it was statistically recorded that the train got faster. It was a total and completely positive feedback, the train at first would continue normally but only in fast-forward, like a video. Those that got off when this acceleration started were lucky; no one could tell how comically depressing the train could get in terms of its speed. At first it was the vehicles that would start to pile up as the natural rhythm of the train became disorganized. It was a month after the veteran’s suicide that another death occurred, this time a student at the local college who mistimed the speed of their vehicle in relation to the speed of the train. They had once ridden on that exact train to get to school. Again, the network engineers, now more observers rather than anyone with technical determinacy, observed an acceleration of speed. This pattern would continue despite all best efforts, and it was in even legend that a culture of suicide existed in Camden that led to the train’s current speed. The train once allowed the shrinking of both space and time, allowing the people the crossing of farther spaces in a shorter amount of time. Eventually, however, as became apparent when looking at the train, which was Camden in the most universal manner. They would be like those surveillance cameras except for the entire town.

The children of Camden would grow up with communal dares to touch that constant beam of light in hopes of being in contact with something that was everywhere at once.

0 notes

Text

Sainte Bernadette Du Banlay (1963) and The Oblique in 20th Century Architecture

Mario Ramirez-Arrazola

May 10, 2024

An acceptable framework for which to understand the confusing historiography of 20th century “modern” architecture is to frame the era as an anxious debate surrounding whether the built environment is at the mercy of either form or function. This dichotomy is primarily understood as a design concern, but the continued integration between architectural discourse and socio-politics allows for these conversations to enter a politicized realm. A particular geometrical aesthetic which rose prominently in the 20th century is the oblique. Immediately, there are a variety of modern architectural figures which have directly employed the use and language of the oblique to their advantage–again, not just simply for design, but towards a political and aesthetic agenda. Those of particular note who employ the oblique are the early 20th century Italian Futurists–specifically Filippo Marinetti and Antonio Sant'Elia–and French-based architects Paul Virilio and Claude Parent, who work in tandem, and of which the former is also quite theoretically based. As far back as 1914 does Marinetti state: “That oblique and elliptical lines are dynamic by their very nature and have an emotive power a thousand times greater than that of perpendicular and horizontal lines and that a dynamically integrated architecture is impossible without them.” Marinetti employs short and blunt arguments to justify a gigantic ambition: the end of classical architecture and the embracement of violence, modernism, war, technology, and speed. Hitherto, how can we understand this development and mobilization of the oblique in modern architecture through a close-reading of these architects? In utilizing Claude Parent and Paul Virilio’s Sainte-Bernadette-du-Banlay Church (1963), along with primary-source written documents from the designers’ themselves (such as the 1997 text Bunker Archaeology), I will move towards an illuminated understanding of this discourse. In the end, there is an attempt to showcase that the oblique does not become mobilized primarily for its functional use (as is immediately inferred) but is rather used as a tool for political and aesthetic means. I will begin by giving an overview of Vilrio’s respective writings’ surrounding the oblique and settle a conceptual foundation for which to understand this concept, including Claude Parent where salient; I will then move onto a close-reading of the Sainte-Bernadette-du-Banlay Church and validate connections between their conceptual drive and its implementation of the oblique; I will end with a general discussion on the form versus function debate in the long 20th century.

In the realm of architectural theory, few concepts have captured the imagination and sparked as much discourse as the notion of the oblique, despite its immediate nicheness within the field. At its core, the oblique represents a departure from the traditional orthogonality of architectural form, introducing a dynamic and destabilizing element into spatial design. However, its significance transcends mere formal experimentation, touching upon broader themes of movement, perception, and social interaction. But contextualization is essential, as to those unfamiliar with architectural discourse it may appear odd to dedicate such careful attention to a mundane shift in geometrical focus.

Paul Virilio (1932-2018), was a French philosopher and cultural theorist. He is renowned for his provocative examinations of technology, speed, and spatiality. His experiences during World War II, including witnessing the German occupation of France and the bombing of his hometown, deeply influenced his later work on technology, war, and urbanism. These formative experiences contributed to his interest in the impact of technology on society and the built environment. Central to Virilio's architectural thought is the concept of the oblique, which he conceptualizes not merely as a formal gesture but as a fundamental reconfiguration of architectural space. In Virilio's vision, the oblique disrupts traditional notions of stability and symmetry, introducing a sense of movement and dynamism into the built environment. Through his writings, Virilio challenges architects to reconsider the static geometries of modernist architecture and embrace the oblique as a means of reflecting the accelerated pace of contemporary life. Virilio also delved into media theory, examining the impact of mass media and telecommunications on society. He was particularly interested in how technologies of communication influence the dissemination of information and the formation of collective consciousness. Parallel to Virilio's philosophical musings, Claude Parent (1923-2016) was a French architect known for his radical architectural theories and innovative built projects. Born in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, Parent's architectural vision was deeply influenced by his experiences during World War II and his subsequent studies in architecture. In collaboration with Virilio, Parent advances a radical architectural manifesto centered around the oblique. Parent's architectural vision is deeply rooted in the belief that traditional spatial hierarchies must be destabilized to accommodate the complexities of modern existence. For Parent, the oblique is not merely a formal gesture but a conceptual framework for reimagining the relationship between architecture and movement. Through his writings and built projects, Parent advocates for an architecture of sensation, where the oblique becomes a catalyst for new modes of inhabitation and experience. Their relationship was strong, but eventually waned due to political differences, primarily in their respective responses to the May 1968 students riots. Without a doubt, Virilio was driving the theoretical and conceptual fervor in their relationship, while Parent was much more pragmatic and hands-on. In fact, they had somewhat of a Marx-Engels relationship, as Virilio was kindly employed in Parent’s office with the title of “chief critic.”

Central to Virilio's conception of the oblique is his broader exploration of speed and perception in contemporary society. In his seminal work, “Speed and Politics,” Virilio posits that the acceleration of technological progress has profound implications for the way we experience space and time. His examples mainly stem from military history and they shift chronologically from medieval to modern times, all in relation to the construction of the city and general urban environment. His historiographical qualification of his dromological theory is highly creative and varied, such as his commentary on siege warfare: “Bourgeois power is military even more than economic, but it relates most directly to the occult permanence of the state of siege, to the appearance of fortified towns, those “great immobile machines made in different ways.” The oblique, for Virilio, becomes a manifestation of this acceleration, disrupting traditional spatial orientations and challenging our perceptual frameworks. Through his writings, Virilio invites us to reconsider our relationship with the built environment, urging architects to embrace the oblique as a means of confronting the relentless pace of modern life. Building upon Virilio's philosophical inquiries, Claude Parent translates the concept of the oblique into dynamic architectural forms that defy conventional expectations. Parent's built projects, such as the Church of Sainte-Bernadette-du-Banlay in Nevers, France, exemplify his commitment to destabilizing architectural space through the strategic use of inclined planes and skewed perspectives. Through these interventions, Parent seeks to engender a sense of disorientation and movement, inviting occupants to engage with space in new and unexpected ways. In doing so, Parent challenges the static nature of architectural form, advocating for an architecture that is responsive to the flux and flow of contemporary life.

At its core, the oblique serves as a catalyst for reimagining spatial experience in the modern built environment. By introducing elements of instability and dynamism, the oblique invites occupants to engage with space on a visceral level, stimulating the senses and fostering a heightened awareness of one's surroundings. In this sense, the oblique transcends its role as a formal gesture, becoming a medium through which architects can evoke emotion, provoke thought, and facilitate social interaction. As we delve deeper into Virilio's and Parent's writings on the oblique, it becomes evident that their exploration of this concept extends far beyond the realm of architectural form, encompassing broader themes of movement, perception, and human experience. Virilio's and Parent's exploration of the oblique carries profound implications for architectural practice in the contemporary context. As architects grapple with the challenges of designing for an increasingly fast-paced and dynamic world, the concept of the oblique offers a conceptual framework for rethinking spatial organization, form-making, and human interaction within the built environment. By embracing the oblique, architects can create spaces that not only respond to the flux and flow of modern life but also actively engage occupants on a sensory and experiential level. The oblique challenges traditional notions of architectural form, inviting architects to move beyond the rectilinear constraints of modernism and explore new formal vocabularies. Speaking less broadly, it will be important to commit towards a close-reading of Parents and Virillio’s 1963 Sainte-Bernadette-du-Banlay Church project to see how these conceptual ambitions manifest themselves in a direct and material manner.

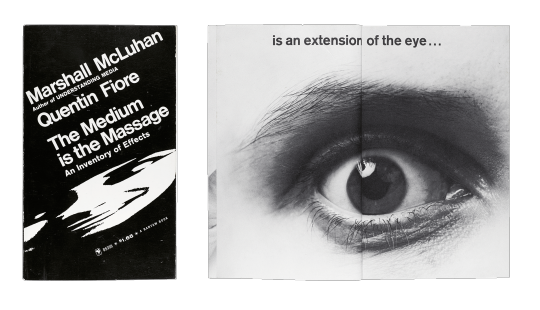

First, we can speak purely experientially through how the project performs spatially through photographs (fig. 1). As one approaches the church, it immediately asserts its presence with a strikingly angular facade, defying the conventions of traditional architectural form. The exterior walls, characterized by their sharp inclines and dynamic angles, challenge the viewer's perception, inviting them to reconsider their relationship with the built environment. Unlike conventional churches, which often convey a sense of solidity and permanence, the Sainte-Bernadette-du-Banlay Church appears almost fluid, as if in a state of perpetual motion. Upon entering the space, visitors are greeted by a dramatic interplay of light and shadow, facilitated by the strategic placement of oblique planes and skylights. The interior of the church is characterized by a sense of dynamism and spatial fluidity, as inclined surfaces converge and diverge, guiding the eye upwards towards the heavens. As mentioned above, central to Parent and Virilio's design is the notion of destabilization, both spatially and perceptually. The oblique surfaces disrupt traditional spatial hierarchies, blurring the distinction between floor, wall, and ceiling.

Figure 1: Claude Parent and Paul Virilio, Sainte-Bernadette-du-Banlay Church, 1963, Nevers, France. Interior photograph.

We can also give a historiographic overview of the church based on John Armitage’s research. To Armitage, the church stands as a testament to their visionary approach to spatial design and their commitment to challenging established architectural norms. The architectural landscape of the Church of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay is imbued with historical and ideological resonances, drawing inspiration from the military bunkers that lined Hitler's Atlantic Wall during the Second World War. This strategic defensive line, stretching over 4,000 kilometers along the European coast, served as a physical manifestation of power and control, reflecting the totalitarian nature of wartime organization. Virilio's fascination with the spatial dynamics of warfare and the transformative impact of conflict on the built environment is palpable in his choice to incorporate elements of bunker architecture into the design of the church. However, Virilio and Parent's intentions extend beyond mere mimicry of military forms. The incorporation of bunker-like structures into the church's design serves a dual purpose: to evoke a sense of protective enclosure and to challenge conventional notions of architectural space. By refusing to adhere to traditional horizontal and vertical planes, Virilio and Parent create a dynamic interplay of form and function, inviting occupants to engage with the space in new and unexpected ways. Despite its formidable exterior, the Church of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay offers a sanctuary of solace and introspection within its walls. The interior space, conceived as a grotto in homage to the church's patron saint, Bernadette, provides a refuge from the outside world. Virilio and Parent's integration of religious symbolism into the architectural design underscores the church's dual identity as a place of worship and a site of architectural experimentation.

Finally, we may speak upon how the oblique continues to permeate contemporary architectural design, both in literal geometrical form but also in the same conceptual fervor as Virilio and Parent originally set forth. Christian Sander's analysis of Virilio's oblique theory offers a profound exploration into the philosophical underpinnings of contemporary architecture, particularly in relation to the dynamics of space, time, and human movement within urban environments. Sander meticulously dissects the contrasting approaches of the Architecture Principe manifesto and dromology, shedding light on their implications for architectural design and urban planning. At the heart of Sander's analysis lies the dichotomy between the Architecture Principe manifesto and Virilio's dromology. The former, championed by Claude Parent, advocates for an alternative vision of urban spaces characterized by pedestrian-friendly environments and a rejection of the imperative of speed. In contrast, dromology, as articulated by Virilio, takes a more pessimistic view, critiquing the hegemony of speed and technology in shaping contemporary urban landscapes. Sander elucidates Parent's evolution from embracing technological fervor to adopting an anti-speed stance, epitomized in his text “Le temps mort.” Here, Parent envisions a city where speed ceases to be a prerequisite for existence, advocating for a recalibration of urban spaces to prioritize pedestrian needs over vehicular speed. This philosophical shift underscores a fundamental tension between the rapid pace of technological advancement and the human-scale experience of urban life. Moreover, Sander underscores the relevance of this analysis to contemporary architectural discourse by foregrounding the ongoing tension between circulation and architectural form. Architects now have unprecedented access to tools and methodologies for analyzing and optimizing circulation patterns within urban environments. Digital simulations and modeling techniques allow designers to anticipate and accommodate the movement of people with greater precision than ever before. However, alongside these technological advancements, there is a growing recognition of the need to prioritize the pedestrian experience and community well-being. The emphasis on efficiency and speed, while conducive to certain forms of circulation, can often neglect the human-scale qualities that make cities livable and vibrant. As such, contemporary architects are increasingly called upon to strike a balance between optimizing circulation patterns and creating environments that nurture social interaction, cultural exchange, and a sense of belonging. As Virilio was originally beginning to make us wary of, there is most definitely a politics of mobility and circulation spawning in the modern era.

As mentioned in the introduction, it is now essential to wrap-around and contextualize our findings within the broader discourse surrounding the form versus function debate that has permeated architectural theory and practice throughout the century. The dichotomy between form and function has been a recurring theme in architectural discourse, reflecting competing ideologies regarding the role of architecture in society and the prioritization of aesthetic expression versus utilitarian purpose. For example, a seminal work within the modern architectural cannon that we can investigate is American architect Louis Sullivan’s (1856 - 1924) “Form Follows Function” design dogma, first elucidated in the 1896 text, The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered. Louis Sullivan famously argued for the primacy of function in architectural design, asserting that the form of a building should be a direct expression of its intended use. Sullivan's dictum became a foundational principle of modernist architecture, influencing architects such as Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius, who sought to reconcile functional efficiency with aesthetic innovation. This emphasis on functional integrity and efficiency represented a paradigm shift in architectural thinking, challenging architects to prioritize the pragmatic needs of users over purely aesthetic considerations. For architects of the modernist movement, Sullivan's dictum provided a conceptual foundation upon which to build their own visions of architectural progress, grounded in the pursuit of functional clarity and spatial efficiency. However, while Sullivan's emphasis on function represented a radical departure from the past, it also laid the groundwork for a new set of challenges and tensions within architectural discourse. The stark dichotomy between form and function, while initially liberating, ultimately proved to be limiting in its simplicity, leading some architects to question the reductive nature of functionalist doctrine. This is where the work of Paul Virilio and the exploration of the oblique in architecture diverge from Sullivan's functionalist principles. While Sullivan advocated for a direct correlation between form and function, Virilio and Parent's conceptual framework challenges the notion of a rigid hierarchy between the two, instead embracing a more dynamic and expressive approach to architectural design. By introducing the oblique as a destabilizing force within architectural space, Virilio and Parent transcend the constraints of functionalism, imbuing their designs with a sense of movement, dynamism, and emotional resonance. In contrast to Sullivan's emphasis on rationality and efficiency, Virilio and Parent prioritize the experiential and perceptual dimensions of architecture, inviting occupants to engage with space in new and unexpected ways.

This nuanced perspective on the form versus function debate is echoed in the writings of architectural theorist Robert Venturi, whose seminal work “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture” (1966) challenged the dogma of functionalism and celebrated the richness of architectural form. Venturi's concept of “both-and” architecture posits that architecture can simultaneously serve multiple functions and express multiple meanings, rejecting the binary opposition between form and function in favor of a more inclusive and holistic approach to design. Venturi's critique of functionalism in “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture” heralded a shift towards postmodernism, a movement characterized by its rejection of modernist ideals and its embrace of plurality, diversity, and historical reference. Venturi argues for an architecture that celebrates complexity and contradiction, recognizing that buildings can serve multiple functions and express multiple meanings simultaneously. This concept of “both-and” architecture challenges the binary opposition between form and function, advocating for a more inclusive and holistic approach to design. In contrast to the work of Paul Virilio and the exploration of the oblique in architecture, Venturi's approach prioritizes complexity and ambiguity over clarity and rationality. While Virilio and Parent embrace the oblique as a destabilizing force within architectural space, Venturi celebrates the richness of architectural form, acknowledging that buildings can embody a multiplicity of meanings and functions. Rather than seeking to resolve tensions between form and function, Venturi revels in their coexistence, recognizing that architectural meaning emerges from the interplay of contradictory elements. In the long 20th century, the form versus function debate has evolved from a simplistic dichotomy to a multifaceted discourse that encompasses a range of perspectives and approaches. While functionalist principles continue to inform architectural practice, architects increasingly recognize the importance of considering the cultural, social, and experiential dimensions of architectural form.

In conclusion, the exploration of the oblique in modern architecture, as exemplified by the works and theories of Paul Virilio and Claude Parent, offers profound insights into the evolving nature of architectural discourse and practice throughout the 20th century. By departing from traditional orthogonality and embracing dynamic geometries, Virilio and Parent challenge the static conventions of architectural form and invite us to reconsider our relationship with the built environment. Through their writings and built projects, they demonstrate that the oblique is not merely a formal gesture but a conceptual framework for reimagining spatial experience, perception, and social interaction.

In our theorization, we may be privy to forget that Virilio’s work had quite the public presence, at the very least in exhibition form. The 14th exhibition (fig. 2) titled “Bunker archéologie”, particularly room 5's display of twentieth-century civil architecture, serves as a poignant reminder of the multifaceted nature of architectural discourse. Among the iconic architectural landmarks showcased, such as the Guggenheim Museum by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Goetheanum by Rudolf Steiner, the inclusion of the church of Ste Bernadette by Paul Virilio and Claude Parent stands out as a testament to the enduring impact of Virilio's exploration of bunker architecture. This transition from exhibition to catalog sheds light on the evolving nature of architectural scholarship and interpretation. What initially began as a series of photographs, devoid of discernible formal attributes yet rich in historical and metaphorical implications, transformed into a tangible manifestation of Virilio's exploration of the architectural remnants of warfare. The inclusion of people in some of the photographs adds an intriguing layer of interpretation, inviting us to consider the human experience within these stark and brutal environments. The juxtaposition of iconic architectural landmarks like the Guggenheim Museum alongside the more utilitarian and austere bunkers prompts us to reevaluate our preconceived notions of architectural significance. By bridging the gap between seemingly disparate architectural typologies, Virilio challenges us to explore the underlying connections and narratives that shape our understanding of the built environment. The inclusion of the Guggenheim Museum, with its avant-garde design and cultural significance, alongside the stark and utilitarian bunkers, underscores the complexity of architectural history and its intersection with broader socio-political contexts.

Figure 2: 14th exhibition “Bunker archéologie”, room 5: “Séries et transformations”. At the center, examples of twentieth-century civil architecture: the Einstein tower by Eric Mendelsohn, the model for a single-family home by Adolf Loos, the Goetheanum by Rudolf Steiner, the headquarters of the High Court of Justice and the Assembly in Chandigarh of Le Corbusier, the Guggenheim Museum of Frank Lloyd Wright, the church of Ste Bernadette by Paul Virilio and Claude Parent (Archives Centre). – ACP 1994W033/074 “Bunker archéologie – Paul Virilio”: communiqué de presse, tapuscrit du catalogue, cartons d’invitations, correspondance, photographies, diapositives, contrats, budget, factures, devis, coupures de presse, projet, 1975-1976.

In this light, the “Bunker archéologie” exhibition serves as a microcosm of the broader discourse surrounding architectural history and theory. Through the lens of Virilio's exploration of bunker architecture, we are invited to reconsider the ways in which we perceive and interpret architectural artifacts, transcending conventional notions of beauty and utility. As we navigate the complexities of architectural discourse, exhibitions like “Bunker archéologie” offer invaluable opportunities for reflection, dialogue, and reinterpretation, prompting us to question, challenge, and ultimately expand our understanding of the built environment and its significance in shaping human experience.

Virilio's philosophical inquiries into speed, technology, and perception provide a provocative lens through which to understand the oblique as a manifestation of the accelerated pace of modern life. His exploration of dromology, or the study of speed, highlights the profound implications of technological progress on the way we inhabit and navigate architectural space. By destabilizing traditional spatial orientations, the oblique disrupts our perceptual frameworks and challenges us to engage with space in new and unexpected ways. In parallel, Parent's radical architectural theories and innovative built projects embody a commitment to destabilizing spatial hierarchies and fostering a sense of movement and dynamism within architectural space. Through his collaboration with Virilio and projects like the Church of Sainte-Bernadette-du-Banlay, Parent demonstrates the transformative potential of the oblique as a catalyst for reimagining the relationship between architecture and human experience.

Looking forward, the legacy of Virilio and Parent's exploration of the oblique continues to permeate contemporary architectural design, both in literal geometrical form and in the conceptual fervor that they originally set forth. As Christian Sander's analysis illustrates, the philosophical underpinnings of Virilio's oblique theory offer profound implications for contemporary architecture, particularly in relation to the dynamics of space, time, and human movement within urban environments. Architects today are called upon to navigate the tension between circulation and architectural form, balancing the imperatives of efficiency and speed with the human-scale experience of urban life. In the broader context of architectural discourse, the exploration of the oblique challenges the dichotomy between form and function that has long permeated architectural theory and practice. While figures like Louis Sullivan championed the primacy of function in architectural design, Virilio and Parent offer a more nuanced perspective that transcends the constraints of functionalism. By embracing the oblique as a destabilizing force within architectural space, they prioritize the experiential and perceptual dimensions of architecture, inviting occupants to engage with space in new and unexpected ways. The exploration of the oblique in modern architecture represents a departure from the rigid conventions of the past and a celebration of the dynamic and fluid nature of architectural form. Through their visionary theories and innovative projects, Virilio and Parent challenge us to rethink the possibilities of architectural space and to imagine new ways of inhabiting and experiencing the built environment. As we continue to navigate the complexities of the contemporary urban landscape, their insights remain as relevant and inspiring as ever, guiding us towards a more responsive, dynamic, and inclusive architecture for the future.

0 notes

Text

The Globalized Border as a Concept and Design

Mario Ramirez-Arrazola

November 5, 2022

The “Border” is both a conceptual and material artifact with no exact designation of which epistemological force has reign. Despite its abstract and vague conceptualization, it has a widespread allure to the general public. Of course, within the United States our interaction with “the Border” is mainly abstract and political, with many of us perhaps never coming into contact with the Border in our entire life; and even further, because of this politicization there is a common spatial designation of “the Border” in correlation with, to be exact, the border which the United States and Mexico share in our southern region. There are, of course, a multitude of “Borders” throughout the globe, and it is an aspiration of this text to bring these to light, creating a globalized discussion on the Border. But, for obvious reasons (one of these being anecdotal, the simple fact that I am Mexican-American and have confronted discourse with the Border quite frequently) there is a special focus on the United States-Mexico border within this text.

As an example, we can begin to visually analyze the United States-Mexico border for its face-value implications, being cognizant of the fact that, though the Border represents a logistically unitary artifact, it can differ from place-to-place. In the United States, stereotypical visual imagery of the wall probably relates to Donald Trump’s “visions-for-the-wall,” in which the Border constitutes a gigantic, mundane, and securitized force… But the wall must also act iconographically, as a representation of the newfound nationalist sentiment within the United States. Removed from these typical representations are zones of the border which are more closely aligned with Hooverville-like visuals. And, as always, there is a constant propagandic battle to depict the Border as stable and highly-defensible, a fact which is constantly proven illusory through phenomenon which are so simple that they prove somewhat surreal in relation to the “threatening” force the Border tries to instill: catapulting humans and items across the wall; makeshift ramps which propel entire vehicles across the border; ant-farm-like tunnel networks beneath the surface to penetrate the above-ground securities of the border, novel ladders, and so on. There are layers to these nuanced forms of representation, in (I believe) the same rhetoric which can be seen in the communal disgust towards Brutalist structures: too withdrawn from passion, too big and too much of an “eye-sore,” too lifeless and devoid of color, too rigid and violent… The Border would be typically taught to be a “construction,” both in its origination but also in the way it manipulates the surrounding community. But, as I hope to have shown here and later on, it also reflects, and it is the job of the designer to navigate both of these arenas.

As a great example of this “constructive” effort, Harel Shapira conducted a typical yet exemplary analysis of the United States-Mexico border within the framework of an interaction between rural and infrastructure studies. In “The Border: Infrastructure of the Global,” Shapira hones in on Adobe, Arizona, a rural town that is located at close proximity to the United States-Mexico border. In general, Shapira seeks to describe local community reactions to border politics, as well as the interaction between national security technology and a community. Shapira critiques infrastructure scholars for long being obsessed with the urban, and vice-versa, as primarily set forth through the metric of cosmopolitanism and globalization. However, she points out that within rural spaces the notion of “globalization” operates much more differently. For the residents of Adobe, globalization means that you can’t go into Mexico to get your teeth cleaned without a passport. It means that every time you want to go to the grocery store you need to pass a checkpoint. It means having to negotiate your relationships to a security and surveillance apparatus. It means that suddenly your identity, as a citizen, as According to Shapira, Adobe is a “made up” name to protect the privacy of the community members. This article is among a collected volume of fellow articles for a Public Culture issue which was dedicated to urban studies and infrastructure. Adobe, Arizona is not “urban,” (whatever that word truly means), but it is certainly “rural.” It is obvious, and only recently taken as an ailment, that architecture has been interested in urban spaces for so long. Contemporary thinkers such as Rem Koolhaas have pressured architecture to pay more attention to the rural. This is particularly interesting as borders, in their political and infrastructural form, are usually located in rural spaces.