Text

May 1

Story

Another story written for a contest: “Scrapbook Season”. And another of my occasional “John O’Hara” imitation stories.

Writing

No writing. Still trying to find my feet again after the sabbatical.

Reading

No reading, either. My, it’s almost as if I’m not back at all.

Movie

Union Pacific (Joel McCrea; d. Cecil B. DeMille. 1939) A troubleshooter has plenty of trouble to shoot as the Union Pacific fights Indians and saboteurs in its race to complete a lengthy line of track. Sweeping Western that moves swiftly and confidently, and is buoyed by a strong central romantic triangle.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Story: “Scrapbook Season”

Every March, Gayle Mason opened her scrapbook to a new page and a new love.

Every March 20, Gayle Mason moved her scrapbook down from the bookshelf to her writing desk. There she would lay it open atop the MS of the novel she had begun composing back in college, and keep it open, turning the sheets every few weeks to a fresh page onto which she could paste photographs, clippings, tokens, and the thin columns of lined notebook paper onto which she jotted notes and reveries as they came to her. She had kept this scrapbook for eighteen years, ever since she was a junior in high school, which is when she had first hit on the idea of memorializing her boyfriends.

This year it would be Robert Decker she memorialized. That was the new boy at the automat where she most often took lunch. (She worked directly across the street as a file clerk at the Continental Life Insurance Company.) At nineteen, Robert was in fact much too young for her—a fact which she recognized—and he looked even younger, hardly more than a boy. He had large eyes and a very slight build, and he combed his dark, thick hair up and back into a rich pompadour that glimmered like an ocean wave at midnight when it reflects the moon.

This is such folly, Gayle told herself every day when she went across the street to lunch. What if someone guesses? It was a worry that had given her more pause than the age difference itself. Gayle liked to be discreet about her boyfriends anyway, and there was little chance the affair would be discovered, unless she were very careless, for she didn't socialize much with any of the women at the office, and all her best friends were back in White Plains. But it preyed on her still, so that she made it a point to sit near the front door, directly by the register, under the watchful eye of the manager, so that neither she nor Robert would be tempted to exchange more than a glance or a smile when they met.

But worse even than the fear of being found out was the fear that went with the infatuation itself. It had a startled, leaping quality, as though the love she felt was a hart she surprised in the forest every time she thought of him. This isn't just folly, she chided herself in those moments when she forgot not to stare at Robert as he bounded past, snapping with energy like a rubber band, bussing the tables. This is more than folly, this is wrongness! There was a sinking regret she felt as well. This is the last time I can ever give my love to one so young. Next year it will be an older man, she told herself, older than Robert certainly, and older than me. It was that promise, she realized some time later, that had given her the courage to lose herself in the giddiness of the affair—as though to gently cup (but with intense concentration!) a mortal flower as it visibly withered, knowing that no such bloom would ever rest in her palm again.

(She liked that image, of the bouquet of a last, fading rose, and she entered it into the scrapbook under a photograph of Robert as he stood waiting for the bus. She wondered why the image of a pressed flower had never occurred to her before. For wasn't that what her scrapbook was, in truth—the preserved memories of things once living, now put back against the day when memories only would warm her against the snows of winter?)

For these were always short affairs, and Gayle always closed her scrapbook on one after six months. The fact was that she feared her own obsessive nature and wouldn't allow herself to love any man too long. It went back to high school, when Patrick Brown snapped their love affair off at the root by calling her a "lamprey" on learning of the scrapbook she had begun keeping on him and herself. And she never pretended with her friends that her affairs were anything but passionate flirtations, and however intense the annual affair might be, she always spoke of it to her friends with a casual insouciance, as an indulgence to be as easily discarded as picked up. Most years she wouldn't even show her beau to her friends, and there were even years she pretended not to have one at all.

So what did she keep in her scrapbook? Gayle preferred symbolic tokens to concrete mementos. Photographs, typically, were the only directly referential ikons that she kept. Even with these, she preserved only chance images caught at a distance, with the man of her affections unaware. (Twice she had taken up a man who worked at Continental, and only of these did she save posed photographs. These often caused her to flinch when she flicked past them, particularly the one snapped at an office party by a colleague who caught her and Bob Anderson together, with her arm loosely hovering at his waist. "Lamprey," she shouldn't help thinking when she saw it.) Otherwise, the tokens she saved were of ticket stubs to movies where she had passed the darkened hour daydreaming of her beloved rather than attending the plot; of pennies mischievously snatched from tips he had left; matchbook covers advertising bars or restaurants into which she had crept to snatch a glimpse of him. Even, in some cases, the birth announcements for his children, when he had been married to another woman.

Gayle never returned the scrapbook to the bookshelf earlier than September 22, which was always the closing date for the affair. This was true even of Robert when he was arrested by the police on a hot July day for cutting open the face of a girl in his neighborhood. Gayle merely added the blotter item to the scrapbook, while everywhere correcting her own misapprehension of his name, from "Decker" to the newspaper's "Duchardt."

Prompt: Title it “Scrapbook Season.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

April (Most of It)

I had to take some time off from writing. It turns out that the month-long writing project took too much out of me.

Besides, I had an old computer game that I wanted to learn how to play again: Civilization VI.

But it's the first of May, which is a propitious day and date to resume old habits. I don't have much to catch up on, so I'll use this post to do it in.

Story

Resuming publication of the stories I wrote in March: "The Black Idol of Zammi." I wrote this for a contest. I don't much like it. A deadline is good for forcing you to write, and sometimes the results are passable to pretty good. This one, I have to confess, didn't make me happy.i

Writing

I wrote nothing since I last posted here. And I don't feel one bit bad about it.

Reading

I read a lot of non-fiction, particularly some heavy-duty books about the economics of the movie industry. (I have weird interests.) For fiction, I started Leigh Brackett's space opera Shadow Over Mars. I'm not sure I'll finish it. It is extremely ridiculous, and not really in a good way. I try to picture it, and all I get is some trashy sci-fi B movie like MST3K would have riffed back in the day.

Movie

It's been a long time since I've watched a movie, but I sat down and powered through one yesterday:

Quo Vadis (Robert Taylor; d. Mervyn LeRoy. 1951) Love and treachery in Rome during the reign of Nero. Tedious Biblical epic relieved only by Peter Ustinov campy performance as Nero.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

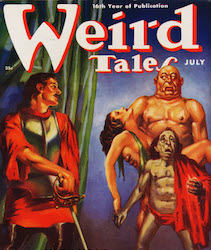

Story: “The Black Idol of Zammi”

Don't feed the bears. Or anything else you happen to find in the woods!

"Ooga-booga!" Max shouted as he leaped from behind the idol. Sheila shrieked and punched him in the arm. He laughed.

"Been waiting long?" Vinnie asked. He'd had to drive ten miles. Not that he'd needed much coaxing: just the promise of weed, whiskey, girls, and a dark place to enjoy them.

"Ten minutes. You bring Frankie and Connie too?"

"I'm here," a girl called as she pushed through the canebrake to join the other three. "Frankie's mom caught him trying to sneak out."

Vinnie grunted. "What is this place? I almost missed it."

"It" was almost invisible under the dark, moonless sky, but with his powerful flashlight Max sketched the outlines of the Temple of Zammi to his high school friends. "Careful you don't twist your ankle," he cautioned as he led them over the broken foundation, which was all that was left of the building proper. Standing incongruously, though, amid the shrubs and grasses that had overwhelmed the lot, were three tall monuments. Two were obelisks, flanking the far end of what had once been a hall. But near at hand was the smaller figure of black, polished stone that Max had been hiding behind. It had a high, dome-like head with a long face, set atop a powerful neck and the bull-like shoulders of a very masculine human body. Its most notable feature, though, was—

"And this," said Max as he shone his flashlight up at it, "is Dickface."

The others stared. Then Sheila giggled. "Oh my God, it really does look like a dick!"

"I think it's supposed to be a trunk," said Max. "Like on an elephant."

"So does he have a dick down where he's supposed to?" Connie asked.

"You think they made him anatomically correct?" Vinnie snorted, while Max challenged, "Why don't you check?"

Connie stepped close to the statue. She craned her neck to stare up at the chin—and nose—that loomed above, and threw her arms around its massive torso as far as she could reach. "You trying to get him off?" Max sniggered as she threw a leg around it too.

"He's wearing pants," she retorted. "It's the only way to find out."

"Look out," Vinnie shouted, "he's coming in the back door!" He poked her in the ass, and she squealed and chased after him.

"So what is this place?" Sheila asked Max as the other two, laughing, vanished into the night.

"I told you. Temple of Zammi. Some cult or other back in the 1920s. They came down from Vermont or Quebec. Built their temple here, pissed off all the local Baptists, then bugged out. My history teacher—"

"Mrs. Cussler?"

"Yeah, she says—"

"She's a Communist, you know."

"Yeah. She says they all got lynched by the town folk, but Mr. Mapes down at the Cultural Center says most of them drifted off to California during the Dust Bowl. All except the ones that got dragged down to Hell!" He lunged at Sheila with claw-like hands and a snarl. It turned into an embrace, and she giggled and relaxed in his arms.

* * *

And that was how the abandoned temple grounds came to be a party spot for some of the high school students. True, it was nearly a dozen miles out in the boggy country down by the river, and you had to know where to turn off the old state highway to reach it. But that was its appeal—you had to be a part of the group to get directions.

Mostly that meant Max and Connie and Vinnie and Sheila. At first casually, and then more and more regularly, that's where they went to smoke weed and drink beer and split into couples when they got bored with sitting as a quartet. Vinnie found a deep depression that fell into a short, square-shaped cave that must have been a cellar or an ice house at one time, and he took to packing camping equipment and other supplies there. That included sleeping bags, and soon weekend nights (and sometimes school nights too) were being spent there, two to a bag, often taking turns at the foot of the black idol—a spot which turned out to be a peculiarly comfortable and satisfying place for doing it.

Curiously, they rarely visited the ruins during the day. No one ever spoke of why. If it was suggested, there would be complaints of the wallowing heat and humidity of the site, of the glare of the sun onto the open field, or the whine and bite of the skeeters. But never did they allude of an oppressive sense of being watched, closely and obsessively, or of the sense that some momentarily paralyzed thing was leaning in on them, eager to lunge. Still less would any of them remark that the locus of that attention seemed to reside in the face of the idol, whose eyes glimmered in the sunlight like liquid and living things.

But neither did they speak of the relief they felt on the cool nights when they basked beneath the approving gaze of the idol, or of the pleasant and lingering lassitude they felt when they woke in the early hours at its feet. Day by day, week by week, they felt progressively drained of willpower, and sometimes they thought—particularly after expending themselves inside a sleeping bag—of how pleasant it would be to dissolve into a dew and sink into the ground at the idol's base.

But though they spoke none of these things, that didn't mean they didn't each feel then.

Then came the day that Vinnie's head got taken off as he rode his motorcycle down the old highway.

* * *

It was a one-of-a-kind accident, the police said. The pipes being hauled on the back of a plumbing-supply truck hadn't been tied down correctly, and one flew off just as Max was shooting past going the other way. It was like being hit with a sledgehammer at a hundred-and-twenty miles per hour.

Max had to help his dad the afternoon of the funeral, but Sheila felt a clawing need to return to the old temple grounds—to commune with the spirit of her dead friend, she told herself—even though it was the middle of the day. She was surprised to see a station wagon parked just past the turnoff when she arrived, and she approached cautiously. She found an elderly man pacing the foundations and squinting about. He saw and called to her before she could duck away, and reluctantly she joined him.

"You know this place?" the man asked, and he mopped his forehead with a handkerchief. Sheila only shrugged. "There's a lot of trash about," he continued. "Someone's been coming out here."

"It's public land, isn't it?" she said a little sulkily.

"Title to it lapsed years ago. But I thought maybe you might know who's been coming out." Sheila shrugged again, and dodged his keen gaze.

She gave a little start, though, when he introduced himself as Donald Mapes. "I'm a local historian," he said. "Though this is a part of the town's history we don't like talking about."

"People got lynched, right?" she said, and didn't bother to hide her hostility.

Mr. Mapes gave her a long look. "Folks would have liked to," he said. "But none dared. Those that looked at the Temple members funny had unlucky accidents."

"What do you mean, 'looked at funny'?"

That only earned her another long look, and a question. "You feel it looking at you now, don't you? The idol?"

Sheila couldn't help shivering a little.

"One of the Temple members left a diary when she left town. They all scattered, of a sudden, you know. It was the only way to escape."

"Escape what?"

"She explained it in the diary, though her mind was starting to go, and you have to put the pieces together. The Historical Society inherited it, but I'm the only one who's ever read it."

He held her gaze with a solemn look, then leaned in close.

"It has to be fed," he said in a low voice. "It's like a vampire, and it has to be fed. It gives back pleasure, too, and even power, if you know how to claim it. But it has to be fed, and the more you feed it, the hungrier it gets. Until, finally, it has to take everything from you."

"Everything?" Sheila breathed the word out.

"It took half a dozen before the rest got the strength to take to their heels. It didn't take them here, mind you. But through accidents. Drowning. Sickness." His mouth tightened. "Even a decapitation."

He looked at her gravely. "You go to the high school, don't you? That's bad. Hard for you to run away."

Three days later, Max was found at the bottom of the municipal swimming pool, which had been closed for the season. No one knew what had drawn him to it, or what had pulled him down and held him under.

Prompt: Cover image

0 notes

Text

April 6

Story

“The Twice-Cursed Outlaw, William Fokke”: Written after trying to watch I Shot Jesse James.

Writing

A good day of writing: quite a lot of interactive stuff, plus a 1000-word science-fiction story that came pretty quickly.

Reading

I am sick of trying to read contemporary teen romances—I haven’t found a good one yet—so I did some digging and found some candidates from the past. I started the 1958 Beverly Cleary novel The Luckiest Girl. It’s very long, and I’m already a quarter of the way through it, and it is much better than the dreck I’d been trying to read.

Movie

Hotel (Rod Taylor; d. Richard Quine. 1967) Multiple stories intersect during the dying days of a grand New Orleans hotel. Superior soap opera, ably elevated by a superb cast and some smart, cinematic direction.

0 notes

Text

Story: “The Twice-Cursed Outlaw, William Fokke”

There's no rest for the wicked, they say. Neither now or after, for those twice-damned.

"Oh, but for you, William Henry Fokke," she hissed, "a special curse!"

Once he would have stopped to listen to the girl, for at twenty she'd been pretty. But five years of Kansas wind and dust had blighted and blurred her face, so—

"Aw, button it, Molly," Fokke growled. He kicked over the spindly pinewood bureau where Duke Winslow was used to keeping his money. Papers and pens and a gold watch on a chain scattered across the warped cabin floor. "You already cussed me once," he said as he picked through the mess.

"The first was that you and Reno and the rest of you ... rascals!" Molly gulped down a breath. "Meet the law and have justice done you!"

Reno, a lean cowboy with a bristly black beard, sniggered. "Yeah, that's us 'n the boys," he agreed. "Jes' a coupl'a rascals!"

"I wouldn' 'spect different from buzzard leavings like you and Homer!" Molly sneered at him. "But you, William! You was Duke's best friend! He tore you out'a jail twice hisself when he coulda ridden back to Missouri and left you to hang!"

"Justice be hanged," Fokke retorted. He was carefully thumbing through a sheaf of bills inside a bulging paper envelope; when he finished, he chucked it to Reno. "You'll get more out'a Duke thisaways too, than you'd of otherwise," Fokke went on. "Fifteen thousand, dead or alive, that's what the territory's offering for your brother. It's yours to collect, soon as me and the boys clear out. Provided, of course," he added with a sour grin, "you 'fess it was you that made that mess over there."

He jerked his chin at the body that sprawled face down in the corner, with the back of its head blown off.

Reno laughed. "Tell the sheriff Duke was always trackin' in the mud," he called back as he and Fokke sauntered out. "That's how come you did it!"

"Ride you on till God Himself in judgement calls you home, William Henry Fokke!" Molly Winslow screamed as he and Reno swung onto their horses. "Neither faithless friend nor kindly foe give you rest nor succor, but let saddle be your bed and sky your ceiling"—still she shouted as the men rode off—"till with sound of trumpet He rolls the heavens back!"

*****

Fokke squinted into the sun and found himself wondering why, at that moment—perched atop his horse, under a tree, with his hands tied behind him and a noose chafing his throat— his mind chose to wander back to that afternoon two years before when, almost casually, he'd put two slugs into Duke Winslow's face.

Maybe because that's when it had all begun to go wrong.

It was easy, afterward, to appreciate how there'd been plenty of takings and hardly any fuss when it was Duke running the gang. Oh, sure, sometimes it was months between jobs, time to be filled with nought but the driving of fence-posts and the stringing of wire and other innocent-seeming play as the law chased fruitlessly hither and fro, even as Duke cased and plotted and dallied thoughtfully over the next bank raid or stagecoach robbery. But it was safe and profitable, even with nothing but drink and cards and whores to relieve the tedium. Afterward, though—

Well, Reno had promised action, and he'd delivered, though more of it and more desperate than Fokke in truth had liked. Worse was the sense he got that Reno and the others didn't exactly trust him after what he'd done to Duke. And when Fokke ran out of the bank in Elko, only to get his ear shot off by Reno as he and the rest of the gang wheeled and rode away, he'd found himself some other pals.

Not that any of the others he joined up with—Johnny Hodges, the Ford boys, the Lincoln County Riders—proved much friendlier. Somehow, their talk always circled back to that day in the cabin in the willows by Shoal Creek. The day Fokke had talked the trusting Duke into a corner, then blown his head off.

But it wasn't the memory of the gun that day—hot and heavy though it had been in his hand—or the thunder loosed by the trigger, or the spray of blood and brain and bone, that preoccupied William Henry Fokke as the sheriff read out the list of robberies, hold-ups, and murders he'd committed since. No, it was—

"You have anything to say before we finish this business?" the sheriff asked Fokke.

"You can't kill me," Fokke replied.

The sheriff snorted. "Like hell."

"Take it up with Molly Winslow."

His objection was followed by a puzzled silence. Then: "That was Duke Winslow's kid sister," one of the posse quietly said.

"Well, we'll be sure to give her an account of the afternoon's festivities," the sheriff drawled. "She'll be pleased."

"Maybe not," Fokke said. "She had other ideas for me, and they didn't include me getting packed off.

The sheriff snorted again. "Okay, let's get along," he said. "H'yah!" He kicked Dutchie in the haunch.

The horse jumped, and Fokke grimaced as the slack in the rope ran out. He felt a momentary jerk— something snapped—

And suddenly he was away. Dutchie sprang forward beneath him as though touched by a hot coal.

Branch broke! Fokke thought, and he laughed aloud. Not a hundred yards away flowed the river, where the sheriff's writ ran out. He bent over Dutchie's mane and coiled the trailing rope about his arm as he ran for freedom.

*****

He bent in the saddle, bowing over his horse's drooping head, as though dragged forward by the weight of his skull. His broken hat fell over hollow eyes, and he felt his bones grinding against each other within the ragged great coat that wrapped about his narrow shoulders. The glaring sun beat down, but he shivered yet, and felt he had no more substance than a stain on the wavering summer air.

Reno and his pals were holed up at the old shack in the willows. How he knew this he couldn't guess, but the thought of it filled him with a grim certainty, and with an unslakable desire to confront them with the fact of his continued—though haggard—existence.

Thrice before he had caught up to Reno, only for the traitor to bolt. The first time, the bristle-headed outlaw had thrown lead while galloping away; the other two times he'd merely run. The last time he'd caught Reno was in the dark outside Elko, and he'd had come close to running the louse down, but the squealing coward had fled into town and flung himself inside a church, sniveling there while his pursuer prowled about until dawn, rattling at the windows and prying at the door. Homer Ford, too, he'd nearly caught, but the fool broke his head open trying to escape down a cliff.

Once, riding after sundown in the Wyoming chaparral, he had lingered on the ridge overlooking a dell and listened to a clutch of cowboys talking around the fire.

"Like to a scarecrow tied atop a starving horse," said one. Another corrected: "A dead horse."

A third swore in a rough voice. "Scarecrow? What's the fear in a thing like that?"

"None, they say, if you ain't one that crossed him in life. Though one feller I heard tell looked him in the face and ain't been right in the head since."

"What's wrong with his face?"

"What do you think's wrong? But I've heard it was worse when there were more bits of him still hanging off the cheek bones."

"It's the neck being broke I can't abide the thinking of," said a fourth. "You reckon his head's wobbling funny, like it might fall off?"

"In that case," laughed the rough-voiced skeptic, "one good shot'd put an end to his riding."

There was a cold silence. "I don't reckon I'd want to cross the Dutchman. He was a bad 'un then, but I reckon he's a lot worse now." He was answered only by a rough, rude laugh.

"He still got the rope on him?"

"So it's reported. He carries it coiled like a lariat, though it's half rotted away. They say he tried roping Hoss Johnson with it at full gallop ... with the other end cinched around his neck still!"

How many miles was he from the shack where he'd gunned Duke down? He didn't know, but it didn't matter. When he got these premonitions he always arrived in time.

He paused at an abandoned homestead, to refresh himself at a rain barrel. The flesh had long since fallen from the grinning face that rippled and wavered back at him in the dark surface of the water; the hair that poked from under the hat brim was like old straw. But the water dribbled vainly through the bony fingers he dipped into the barrel, and the withered hand had no strength to lift the tin cup that hung on a nearby nail.

Prompt: Living death.

1 note

·

View note

Text

April 5

Story

“The Maze at Kilgetty Hall”: An attempt to write a ghost story in the manner of M. R. James. But it was for a contest, and I feel the final result was greatly hampered by a very strict word count. Oh well.

Writing

Some interactive writing, and a 1500-word short story.

No reading and no movie.

0 notes

Text

Story: “The Maze at Kilgetty Hall”

What horror stalks the garden at night?

My dear Robert,

You know I am not in the habit of apologizing to servants or retainers. Nevertheless, when you are next at the Hall, you may expect from me some gruff words that resemble such. I am writing now that I may explain.

When you were here last it was to go over the terms of certain bequests I was making. One such term, attached to the Hall, was an absolute prohibition on the presence of any child under the age of majority inside the park. You queried this. In reply I believe I uttered an oath to the effect that you should leave my business to me.

Well—

It is the garden, in particular a certain triangle of it, that explains this prohibition. You know the place. In the crook between the north and east wings of the Hall stands the shabby remnant of a small hedge maze, itself walled off from the garden by a rampant wall of blackthorn and broom. You once asked why I allowed such a wild growth to fester. Then too I had for you words for which I must apologize.

I will begin to explain by recalling to you a tradition that Mary Allingham, the "witch of Grimpen," was extinguished at Kilgetty, though the historical fact is only that the sixth duke presided at her trial. I will also remind you that it was the disappearance of the seventh duke's young heir that caused the title and Hall to pass to my branch of the family.

My own father and grandfather made it a great point to keep the maze locked, and forbade me from approaching it. I remember once being caught too near it by my nurse, who shook me most violently and said if ever I wandered into its depths I would be absolutely lost and never heard from again—"no matter how loud ye cry," she said, words which made a lasting impression on me.

Only once, and at great provocation, did I ever penetrate the maze. First, however, I must describe what I had learned about it by then.

Among my great-grandfather's papers are extracts from a diary kept by his uncle, the seventh duke. I set out here my own fair copy of those passages that seem to me most pertinent.

July 27 Mary Allingham, reputed wise woman is to be ["examined" possibly; the seventh duke was only nine here when he wrote] tried in the morning. Father sits as one of the judges.

July 29 The witch hath somehow fled. Georges says he saw her cat darting into our park at dawn. Father threatened to whip him if he does not hold his tongue.

August 5 Much tumult in maze last night, and uprore [sic] indoors.

August 8 Three nights of great tumult within maze, as though a bear has got trapped inside. Georges confirr'd [sic] long with Father.

August 18 Father [remonstrated?] Georges at length—maze gate found swinging open. I overheard [Margery?] telling Mrs. Jenkins of a shadow slipping in and out of the maze, but she was [stifled?] when I was glimpsed.

August 22 A babe dead in the village, which we learned when a [deputation?] visited Father. All looked [frightened?] afterward. Father has quite forbidden me to stray from the house.

September 2 Another babe is dead. Father has ordered me to pack for London. I leave tomorrow.

I quote one passage from a single page, date much later:

May 6 I see that the blackthorns my late father caused to be planted across the face of the maze have come in magnificently. Old Georges takes great pride in them, but became quite stiff when I asked if it would be practicable to open the maze. He made much of the fact that my father had ordered the pathways within be planted with asafoetida as an influence against evil.

I will not quote the entries concerning the disappearance of the duke's young son, but only note that his grief and horror, which undoubtedly contributed to his early demise, are quite plain to read. Though at first it was presumed the child drowned in a recently dug well, the duke becomes morbidly concentrated on the fact that the gate to the maze had been found "swinging wide" the day the child vanished. He complains too of hallucinations—or so he takes them at first; his doubts on that score grow—of the voice of a child crying from out the maze in the nights that follow his son's disappearance.

I come now to my own experience with that part of the garden.

We had had a garden party there only a week before—a charming time until it became an occasion for distress and, finally, bereavement. I have never told anyone the sequel, and I charge you now to keep it to yourself as well.

My own bedroom overlooks the maze, and in fifteen years occupancy I had never once been disturbed by any commotion from it. But I was awakened one night shortly afterward by what I took to be the voice of a child crying out wordlessly. I tried shutting it out—there are many night creatures whose voices can uncannily mimic that of man—but was finally driven to open a window and look out.

There ought to have been little to see in the maze below, for the privets have completely closed in over the pathways. On this night, however, there was great agitation to be seen in the shrubbery, as of some heavy beast attempting to shove its way through, and again I heard a child calling in great terror. I immediately took to my heels outside.

The gate was as ever locked, but by the light of my lantern I saw fresh dirt beneath one of the blackthorns, as though a burrowing animal had tunneled its way in. I was both fearful and hopeful at this, for it would explain how the child I heard could have entered the maze. I instantly roused the gardener, and we got the key to the gate.

There seemed little prospect of becoming lost within. The maze is quite small, and we would be breaking branches as he pushed through. And yet almost immediately on glancing behind I found that I had lost Edwards. Worse, the flame in my lantern began to fail intermittently. The walls too had grown so close together that I found it impossible to tell if I were pushing along a pathway or through one of the hedges.

After a moment of panic, I endeavored to push in a straight line, thereby to break out or run into the brick wall of the Hall itself. This hope proved delusive—either I was walking in circles or some enchantment had bewildered my sense of direction, for I only ever pushed aside more branches. In my struggles I was further unnerved by the sobs of that terrified child, and still more by the rattle of something immense rending its way through the hedges. I was quite certain before long that some thing was actively on the hunt inside the maze with me, and more than once I cowered in place as I felt it push past.

I was nearly at my wits' end when I tripped onto my face. This was fortuitous, for between the roots of a hedge I saw the glimmer of the open gate.

But before I could attain it, something stepped between me and it. I beg you to believe me when I say that it was the leg and paw of an immense cat. You will insist I was baffled by the darkness, but I will maintain it had the girth and stamp of an elephant's foot. Certainly the hedge between us shivered and shook as though it would be uprooted.

I covered my head with my hands. When I looked up again—I know not how many minutes later—the way was clear, and on my stomach I bellied out. Though it had been blackness itself within the maze, and barely midnight when I entered, it was a bright and cloudless morning that I emerged into.

Edwards I found in his cottage, drunk, and I discharged him on the spot, for which he gave me copious thanks when next we met in the village.

The maze I shut again, though for the next week I continued to endure to the wails of some bereft infant echoing from within. Then silence closed over it.

Whatever dwells within that maze I believe had not the power to trap me there, as it may be trapped, only to confuse me as it is confused. But I am less sanguine about those that it preyed upon in the days of the sixth duke. For that reason, I will not suffer any child to approach nearer the maze than the foot of my own carriage drive.

You may remember the garden party in question. It was the day that the Haydon child went missing.

Yrs, etc.

0 notes

Text

April 4

“Clio and Thalia”: This is another one of my “John O’Hara” type experiments in short fiction.

I did not get a lot of sleep on Saturday night, so Sunday was a mess in which I didn’t get a lot done. I wrote some in the interactive, and I started revising one of my contest-entry short stories to lengthen and deepen it beyond what I could accomplish within the word count constraints. Otherwise, nada.

0 notes

Text

Story: “Clio and Thalia”

News is made over lunch.

"Breaking news!" the red-head exclaimed as she dropped her purse onto the middle of the starchy tablecloth. "I'm going to Greece!" She fell into the empty chair.

Opposite her, a woman with bobbed blonde hair laid her book aside and said, "For real?"

"No!" The red-head laughed. "I couldn't afford to go to Greece even if I wanted to! Besides, I've heard it's filthy. But it's what I've decided to tell Chuck and David and the rest of the gang."

A green-aproned waiter decided that her appearance was the signal to begin serving. He stepped up and without seeming to nudged the purse aside to set a basket of dinner rolls beside the centerpiece. He then filled the women's water glasses.

"So is it supposed to be a vacation?" the blonde asked. Like her friend, she appeared to be in her mid-thirties.

"No, it's consulting work. Isn't it wicked? I've been hired as a consultant by a film company. They're making a miniseries about the Greek War of Independence, and I'm going on location to consult!" She laughed, showing her teeth.

"It sounds incredible," said the blonde.

"In what sense?"

"In every sense. Are you really telling people—?"

"I told David just now. I went into the department to check my mailbox, and he came creeping out to ask if I'd found a new position yet. I just popped out with it. 'I'm going to Greece to do some consulting work on a miniseries.' You should have seen his face!"

"Mm. So how did you find this job?"

"I think it must have been an old college roommate. She— Or he. Maybe I should tell them it's an old boyfriend. I think he's trying to respark something between us, he's been waiting forever for me, and—"

"That also sounds incredible."

"Well, I couldn't have just read it somewhere and applied! Something like this has to be chance or serendipity." She picked up a menu and glanced over it. "And I'm telling you now so that if anyone asks you—"

"Alright, that's what I'll tell them if I'm asked. When do you have to be out of your office?"

"Day after tomorrow. Chuck's being a real prick about it, too, he— Oh, did I tell you I flipped him off the other day?"

"No!"

"Yes! I was stopped in front of the Frostee, and I looked over and— God, it seems like he's around every corner I turn these days."

"It's a small town."

"A small university town. They're the worst, right? Universities are like small towns anyway, and when you stick one inside another— But I was telling you I flipped Chuck off. He was standing on the corner waiting to cross, wearing that dumb expression he gets on his face when he's try to remember, like, how many Russian czars were named Feodor, and I just flipped him off."

"Did he see you?"

"No, I had the air conditioner running."

"Was he coming out of the Frostee?"

"No, I think he was coming from Butler's. He had a small sack with him and it looked like it had some books in it. Oh, what's that you're reading?" Without asking for permission, the redhead picked up her friend's book and read the cover aloud. "The Fool on the Hill. That could be Chuck's biography!" She dropped it—a heavy hardbound of several hundred pages—back on the table with a thump. "So who's the fool on the hill?"

"Thaddeus Gascoyne. It's a biography."

The redhead's eyes popped. "Not another biography of Thaddeus Gascoyne! That's the fifth this decade, right?" Her laugh escaped through her teeth with a hiss. "By the way, who's—?"

"Some nineteenth-century abolitionist-poet, a friend of Emerson and Wilmot." The blonde looked abashed. "I never heard of him either, but my own chair suggested I review it."

The redhead spun the book around to study the cover. She snorted as she tapped it. "So I wonder who she's sleeping with that she got a book contract with—?" She lifted the book to examine its spine. "Oh God!" she chortled. "Oklahoma Press?"

"Well, it's a living."

"Not much of one! Not if you have to work for Oklahoma Press, or have to write books on abolitionists no one's ever heard of!"

They fell quiet. After a minute, the redhead glanced around the restaurant with a querulous expression. Then, with a start, she seemed to notice the basket of rolls for the first time, and she plucked one up and broke it open.

"It's one of the cable channels," she said in a distracted way. "One of those nature-slash-documentary-slash-history channels. But one that no one's ever heard of."

"Who is?"

"That's financing this miniseries I'm consulting for. It's a multinational thing, there's a British and a French and an Italian company, but it's the American cable channel I'm—"

"Is there a Greek one in there?"

"Oh, I suppose so. That's what I'll say if I'm asked. 'I suppose so'." She tore open a butter packet. "But you know, I'm just there to consult and collect a paycheck, I don't pay attention to the business side."

"They'll believe that at least."

"I don't care if they believe any of it!" she said with a sudden, wild fierceness. She wiped the butter across the soft center of the roll and muttered some filthy words. "I almost hope they don't!"

The waiter came up and quietly asked if they were decided yet. Both women ordered salads. The blonde also ordered a sparkling water, while the redhead ordered a whiskey sour. They began talking about plans to go sailing that weekend on a nearby lake, for the weatherman was promising seasonable temperatures.

Meanwhile, a man had been listening to them at another table. Eventually his frown cleared up, replaced by an expression of relief.

Oh! he thought. Her car has tinted windows. That's why whoever couldn't see her. And she had the windows up because she had the air conditioner running.

Prompt: Use "breaking news," "waiting forever," "around the corner," "fool on the hill."

0 notes

Text

April 3

Story

Today, a science-fiction story: “Natural Immunity.”

Writing

Some writing for the interactive. Nothing else, though.

Reading

I finished What Makes Sammy Run? There are some notes on it nearby.

No movie.

0 notes

Text

Novel: What Makes Sammy Run?

Story

Al Manheim is the drama critic for the New York Record when he meets Sammy Glick, a 17-year-old copy boy who even on his first day betrays an exuberant drive and ambition, and doesn't scruple to play every dirty angle he can in order to get ahead. Sammy quickly gets himself a columnist position (which entails taking away some of Manheim's space) and uses a radio script by a naive playwright to get himself a contract as a writer in Hollywood. Manheim also moves out to Hollywood, and gets a close view of Glick as he schemes his way upward from lowly screenwriter to well-paid screenwriter to B-movie producer to head of the studio. Throughout the book, Manheim wonders what caused Glick to turn out the way he did, and he eventually solves the puzzle when he learns about Sammy's childhood. At the end, the moralizing Manheim is able to console himself with the conviction that although Glick has achieved everything he wants, it will never bring him happiness.

Notes

This classic Hollywood story—written by the son of one Paramount's founding producers—is sharply written, and in Glick it creates one of the most vivid characters in literature. But as a novel it suffers from three defects:

1. The point-of-view character, Al Manheim, has no distinction, no drive, no goal, and no purpose save to watch and muse fretfully over Glick. Although page by page the novel crackles with energy, chapter by chapter it drags because it never advances. Manheim's own character becomes unsatisfactory because, with nothing to do but comment on Glick, he comes to seem as obsessed with Glick's faults and flaws and Glick is obsessed with achieving success. Glick is so amoral he is repellent; Manheim, so moral he is almost as bad. In fact, I would rather spend time with Glick than Manheim. Glick is interesting to be around, and as a sociopath is almost as innocent as a tornado. Manheim is just wearying.

2. There are really only three characters in the book: Glick, Manheim, and Kit Sargent. (Even Julian Blumberg, the nebbishy writer whom Glick exploits, has only a few walk-on bits.) For a world as large as Hollywood, it feels undernourished and underpopulated. Without additional characters and stories that can be woven around Glick's, there is nothing to contrast Glick's amorality with. Manheim disapproves of Glick, but there's no one in Glick's position who he approves of, which means that his disapproval comes to seem personal and dyspeptic, not moral.

3. The novel is reductionistic in its moralizing, putting Glick's deformed character down the horrors of his childhood. This may be (and it certainly seems plausible) but in making his defects mechanical and neurotic in nature, it either eliminates the novel's moral judgements, or makes the job of moralizing over Glick so complicated—how do you balance Glick's demolition of the moral law with the accidents and exigencies of childhood environment?—that the moralizing becomes trite and officious.

Lessons

There is only one technical lessons here: Make sure your POV character has something to do. Otherwise, there are only cautions. (1) It is dangerous to write for a moral purpose, for the facts you invent to moralize over may not suffice to support the judgement you wish to make. (2) If writing a character study, which What Makes Sammy Run? ultimately is, create a number of other characters with which to contrast them.

This is a very good book. It would have been genuinely great if it had been three or four times longer, and even more dense.

Recommended.

0 notes

Text

Story: “Natural Immunity”

Nothing ever means to evolve a defense mechanism. But sometimes they just do.

Captain Eugene Chodor crossed his arms and settled back on his heels. "Maybe it was mutiny?" he suggested.

His blandly handsome features looked even blander and blanker than usual as he spoke, and he smiled at his own suggestion. His blue eyes were clear and placid. But beneath the good humor there was a tightness in both his voice and expression.

"There's never been a mutiny in the Space Force," ship's surgeon Hans Pruitt replied. He balanced on his haunches and fiddled with a long stick. Every minute or so he had to brush back the soft, crimson petals of the gargantuan flower that threatened to engulf him. There was a whole canopy of them overhead, big as beach umbrellas, nodding gently in the perfumed breeze that gusted softly from the nearby beach.

"There's precedents if you know where to look," the captain said. "The Bounty."

"Was the Farsight's captain a Bligh?"

"Bligh wasn't a Bligh." Chodor paused. "And would you please stop poking at it?"

"It" was a silver boot, of the same style and manufacture as the ones he and Pruitt wore: a thing issued by the United Earth Space Force. It was light, comfortable, and sturdy: designed to be as close to the experience of not wearing a boot at all as possible.

And like, the boots he and Pruitt wore, it had a human foot in it—the bones of one, at least. The difference was that these bones weren't attached to any leg.

Pruitt tossed away the stick he'd been using to push the boot this way and that. He wasn't a fastidious man, but the boot was evidence, though neither man knew what it was evidence for. "Do we tell the others we found the crew of the Farsight?" he asked.

"We only found one," Chodor pointed out. "And only part of him."

Star HDEX 396671 was a yellow dwarf with two terrestrial planets in its habitable zone. The system had long been on the Space Force's "to explore" list, but its distance and position relative to other stars of interest had pushed it nearer the bottom of the list than the top. That had changed, though, when the ESS Farsight finally staged a visit, and reported not merely an Earth-like climate for one of the terrestrial planets, but nearly an Edenic one.

For three months the Farsight had sent back a steady stream of data so enticing as to be incredible. Mild temperatures in both northern and southern hemispheres, even at maximal axial tilt. Landforms that took the shape of small to medium-sized islands in a belt at low latitudes about the equator. Abundant ocean life. Even the vulcanism was restricted (to all appearances) to gentle eruptions that replenished the soils and atmosphere without undue violence.

The terrestrial fauna too was uncannily benign. There were no aerial creatures larger than a sparrow, nor any land-dwelling ones larger than a house cat. Some few were carnivorous but hardly dangerous, and the explorers reported that one rodent-like creature was so soft, inquisitive and friendly as to be irresistible.

Only the "elephant trees," as the Farsight's botanist had christened them, daunted. They were Brobdingnagian, and they dominated every island. Their trunks were squat, fat, and turnip-shaped, like an African baobab, but they sprouted at the top into a hydra-like cluster of flexible necks that drooped almost to the ground and opened into enormous, floppy-petaled flowers. At their base they sprouted sprays of fern-like fronds that choked every avenue between them. Inside these fronds and within the flowers nested broods of almost every terrestrial animal discoverable by the Farsight surveyors.

Then the explorers had fallen silent. When contact couldn't be reestablished, the armored corvette Paladin was sent to investigate. It had spotted the derelict ship easily, but for safety's sake had set down on a beach one kilometer from the glade where the Farsight placidly rested, so that her men had to slash their way through luxuriant undergrowth to reach it.

The boot was in the sickbay freezer when Lieutenant Tristan Miller—a mission specialist assigned from Port Ganymede—and Ensign Paul Shadansky emerged onto the beach from the dense jungle that covered the island's low hills. "Run into anything?" the captain asked.

"Aw, shoot, cap'n," the ensign said. "There ain't nothin' worse 'round here than what's in my mama's flower box back home."

Chodor cocked a querying eye at Miller, who shook his head.

"I've been through everything they left behind," he said, "from her log to her crew's private recordings, backward and forward, ten times. Whatever got 'em, it got 'em sudden. They didn't see anything we haven't seen ourselves."

"Which is nothing," Shadansky added.

Chodor wished the lack of evidence didn't leave him even more jittery. He set Shadansky to patrolling the landing area—which in practice freed him to build sandcastles and splash in the surf—while he took Miller inside to show him the boot. "Where'd you find it?" Miller asked.

"Frenchie found it." That was the engineer of the five-man corvette. "Rather, he found a belt buckle with a detector. Pruitt and I dug around deeper. We turned the boot up nearby, under one of those big flowers."

"Can you show me where?"

"I can show you the trench. I can't show you anything in it, because there isn't anything."

Miller pondered the boot for some minutes. "Dismemberment," he finally said.

"That was my thought," said Chodor. "But where are the mutineers?"

Miller squinted at the wall behind the captain. "If it was me, I'd make a canoe and paddle as far away as possible."

"If they were rational," the captain said. "But I've been thinking, what if they weren't?" He poked at the boot with a pencil. "I mean ... dismemberment."

"Spores?" suggested Miller. "Spring is breaking over this hemisphere, and it was almost a year ago, local time, that the Farsight fell out of contact. If those flowers release some kind of pollen— Well, it might be a good idea to reissue the filtration masks."

"I'll put us in orbit on the equinox, just to be extra safe. Mind you, if it turns out there's nothing toxic, it's going to look very bad."

"Why's that?"

Chodor got a pinched look, and he folded his hands.

"We've stopped sleeping in the ship," he said. "Shadansky and Frenchie don't even bother putting on their uniforms anymore, and go about in their jumpers. The doc is growing a beard."

"It's more comfortable," Miller said with a shrug.

"Discipline is breaking down bit by bit."

"So restore it. Give Pruitt a razor and—"

"I don't want to," Chodor said. "And that worries me. It's so ... soft ... here." He made a face. "And it worries me that I'm not worried enough about it."

"So what do you want me to do?"

"Help me worry? I said it would be bad if there was nothing toxic out there. What I meant was—" He paused. "I mentioned the Bounty to the doc. He thought I meant Bligh. But I was thinking of Tahiti."

Miller mulled the name. "But then it would be a one-off," he said. "The Farsight, like the Bounty, but not like the ships sent after her."

"Unless the planet itself is somehow toxic."

Miller's eyebrows shot up. "Toxic against what? Invaders like us? How would that work?" But Chodor could only shrug helplessly.

A week later the equinox arrived. It was one of the hardest things he'd ever had to do when Chodor pulled Shadansky and the others from the surf and packed them back into the Paladin.

"It seems a damn shame," the ensign grumbled as they watched the planet from orbit.

"What is?" The captain had been watching the ensign closely ever since blastoff.

"That down there. Nothing but gentle seas and bobbing flowers and tame little critters. But it's all gonna get itself spoilt." He lowered his head. "First they'll put in a space port," he growled. "Then they'll cut down all the flowers and trees. The high-rises will go up and they'll pour asphalt everywhere. And if the survey teams find any minerals—"

"How far would you go to stop that from happening?" Miller asked.

"Sir?"

"You understood me."

The ensign thought a moment, then shrugged.

"Just seems a shame," he said, "to take it away from Tuffy and his friends."

"Who's Tuffy?" the captain asked.

A fistfight was only narrowly averted when Chodor flushed the titmouse-like creature Shadansky had smuggled aboard out the airlock as a "dangerous possible contaminant."

For two weeks, the Paladin rolled in an elliptical loop about the planet. The first week was the hardest, as the crew readjusted to wearing uniforms (and boots) again. Pruitt was persuaded to shave. But even the captain felt the confinement of the "tin can," and broke his own intention by dropping back to the surface a week early, and he too breathed a sigh of happiness as the landers settled into the sand.

They had taken copious air samples before departing, and these were carefully compared to new ones. No detectable difference was found. Still, the captain ordered ventilators and pressurized suits be worn.

They had spent nearly an hour conducting additional tests when Frenchie called their attention to one change: "Where are the birds?"

Indeed, the absence of the birdlike chirping was almost intolerable once they noticed it. Then Shadansky pointed out that the mouse-like animals he had tended were also gone. "Let's do a forest survey," the captain said. "Everyone stick close," he added as the five crewmen struck into the jungle.

The underbrush, if anything, had grown even denser in their absence, and the track they'd beaten to the abandoned exploration ship was completely overgrown. The canopy had lost all its color, too, for the flowers had withered and the petals fallen, leaving only sinewy pistils the size of a man's leg. They looked remarkably like elephants' trunks.

"These must be the 'proboscises' the Farsight crew noted," Pruitt said as he paused to study one. "Captain, may I take one back to the ship?"

"Why?"

"These are one of the last things the Farsight's crew noted before—" He broke off. "We could pick up where they left off."

Chodor nodded, even as he was bothered by a premonition. Here they stood under the same canopy as the crew of the Farsight. Those men had been oblivious to danger, and had vanished. But though he was almost paranoid with trepidation, he had no more notion than they about the direction and form the danger might take.

So he was watching Pruitt closely, and approving at the way the doctor carefully approached the pistil with gloved hands, when he saw the thing curl, flex, and seize the doctor's head with a crimson-flecked maw. It was like watching a pig get sucked down by a python—or an immense vacuum cleaner hose—as Pruitt shot up through the writhing proboscis and the connecting stem to vanish into the body of the plant.

The proboscis shivered hard and a blew out a wet bubble of blood. When it popped, something fell to the ground.

It was one of Pruitt's boots. From out its top protruded nothing but a bit of white bone.

And the whole thing had made no more sound than a sigh.

Captain Chodor tore his eyes from the boot to gaze back down the long, winding path they'd cut through the forest. Everywhere overhead dangled the green proboscises, now curling and flexing and feeling at the breathless air like the elephant trunks they so uncannily resembled.

A defense against us, the captain thought with borderline hysterical humor as he remembered Shadansky's doleful regret at the planet's likely development. The planet hadn't meant to evolve one. But with these flowering trees—which lulled and nurtured life through the winter, only to devour it in the spring—that's exactly what it had done!

Prompt: What unexpected delights or dangers come with the advent of spring?

0 notes

Text

April 2

Story

Another horror story today: “The Resurrection of Meleck-Taos.”

Writing

I did some writing in the interactive, but I also wrote a 1500-word ghost story. So, a very nice day.

Reading

Read another 20% of What Makes Sammy Run? I am more convinced than ever that the novel, though interesting, is fatally unbalanced by its POV and lack of subsidiary incident.

No movie.

0 notes

Text

Story: “The Resurrection of Meleck-Taos”

What infernal life lay slumbering in the crib?

"It is well the infant has been recovered," my colleague Dr. Percy Belknap told the police sergeant. "Where is it now?"

"Returned to the maternity ward at the hospital," he said. "Unharmed."

"And the nurse who abducted it?"

"Still missing." The sergeant pointed to a black jitney parked down the street. "But that's her car. We're making house to house inquiries."

My mentor pulled me aside as the policeman left us.

"We will leave them to search this side of the street," he murmured. "But you and I—" He nodded at the cemetery that glimmered in the moonlight. From the trunk of his touring car we removed lanterns, an iron stake, and a silver dagger.

The kidnapping of a newborn infant, though tragic, would not have concerned us, save that our trail and that of the police had intersected in one person: the nurse who snatched the child from the hospital. Our own researches had suggested—and our questions at the hospital confirmed—that she was an initiate of that most infernal of cults, the Temple of Meleck-Taos!

We had thought the Temple derelict, until news came that its most verminous relic had been stolen from the vault where our own society kept safe from evildoers the most terrible and potent of occult artifacts. In hasty fear we had mobilized.

Hunched over, with our faces turned to the ground, Belknap and I found a set of tracks through the graveyard, and our boots sank into the soft turf as we followed them.

"Look, there!" Belknap lifted his lamp and pointed. Something in white garb was stretched on the grass in the shadow beneath the bone-white wall of a marble mausoleum. He lifted his lantern over it.

"The nurse!" I exclaimed as the shadows fled from the woman's pinched and bony face. "But why?" I asked. "Plain murder after she had served her purpose?"

"Don't forget the tattoo that was observed on her wrist. She was one of them!"

"Are we successful then despite ourselves?" I asked. "Did the tools break in their hands?"

Belknap didn't answer right away, but mused to himself.

"A sacrifice was necessary," he said, "if they were to employ the altar-stone. These are fanatics, and we must put neither murder nor willing suicide beyond them. Yet it is more likely they would murder an innocent if they had one to hand."

"The child? But it yet lives!"

Belknap glanced about with a frown until something caught his attention. He plucked my elbow and drew me around first one corner of the mausoleum and then the next, until we stood, staring aghast, at the object that sat opposite the side where the nurse sprawled.

It was a crib. My brain was hot as I comprehended the concrete proof of the intended depravity implied by its presence. Still—

"Were they interrupted?" I asked. "The child recovered before they could—?"

Belknap made a circuit of the mausoleum, examining it from every angle. "Look," he said, lifting his lantern to illuminate the lintel over the door. "Here is confirmation of their intention at least. The name of Ulysses Fordham, last high priest of the Temple!"

"And the last to attempt the ceremony," I observed.

"Exactly. Remember the description of his death. A blue flame like a finger burst from his forehead and burnt there for some minutes before expiring even as he did. The demon, baulked by the holy water surreptitiously traced there by my old teacher DeCamp, was prevented transference into a terrestrial abode until death had embraced the would-be host. And so here," he grimly concluded, "trapped within desiccating bones, hath the terrible Meleck-Taos slept these five decades. Until another acolyte was able to steal the altar-stone and effect the ceremony!"

"Monstrous!" I exclaimed. "Monstrous! To sacrifice any living thing to resurrect that—! But to snatch from its mother's arms a—! Faugh! At least they failed to carry out their scheme!"

"It is indeed monstrous," Belknap agreed in a voice husky with fear. "But you speak too quickly if you think they failed. You do not read the signs as I do!"

"What do you mean?"

He pointed. "See where they placed the crib. On the east side of the mausoleum! Facing the Luciferean star!"

Indeed, now that he drew my attention to it, I saw that he was right. But that meant—

We hurried around to the other side. Belknap gripped the nurse's corpse by the shoulder and turned her onto her face. Beneath her lay a slab, and by our lanterns we saw the horned star carved into its center.

"The altar-stone of Meleck-Taos!" my teacher whispered.

"Why did they abandon it?" I asked.

"Do you not see? They came within a whisker of failure! They must have heard the police, seen their lights, and fled ere they could remove all their vile tools! Oh, but they didn't neglect to pluck and carry off the foul fruit of their labor!"

"The child?"

"Indeed," he groaned. "It was the nurse they sacrificed to effect the exchange. The vessel for the demon—" He tramped around the mausoleum to point a shaking finger at the crib. "Lay there!"

It took a moment for my horror-benumbed brain to comprehend what he was saying. "Then the infant that she stole from the hospital—"

"Is now the physical embodiment of the resurrected fiend!"

I felt myself reel, and put my hand on the crib to steady myself. It was hot beneath my palm.

Still, I tried to rally. "There is yet time to stop them," I said. "If we could not prevent his resurrection, we may yet—"

"No. We have lost," Belknap murmured.

"It is loathsome," I admitted, "but is it really cause for despair?"

"Oh, see you not the deviltry of it?" he cried. "Even if we found it, and even knowing what it really was—!" He showed me the cruelly sharp iron spike he clutched. "Could you drive this into the beating breast of a newborn babe?"

Prompt: A cradle in a graveyard.

0 notes

Text

April 1

Story

Another pulp story: “The Prophet of Dagon.”

Writing

I took the day off. It was the day after completing my March challenge. Also, I got a COVID shot which kind of messed the schedule up.

Reading

Read more of What Makes Sammy Run? It’s not bad—not bad at all—but there are a few things about it that make me wonder if I’ll really be able to persevere to the end.

No movie.

0 notes

Text

Story: “The Prophet of Dagon”

Some excavate in order to study the past. Others excavate to unleash it!

"Gentlemen, our guest of honor!"

The president of the Royal Archeological Society with a beaming but perspiring face raised his glass to the man seated on the dais to his right. I rose with the rest, and with a smattering of applause and a few hoarse hear hears we of the Society (to our own sullen amazement) also lifted our glasses to toast the health of Baxter Carswell.

He was a small man with dark hair and pinched features, and even when he smiled—and I suppose he was trying to smile as we cheered him—his face tended to curl into something between a grimace and a scowl. He acknowledged our applause with a quick wave of his palm, then hunched in his seat.

"Perseverance— Perseverance and scrupulosity," continued our president, "are two of the virtues without which no archeologist can hope to succeed. Without them—"

And so he was launched.

Professor William Stapleton was a man of some twenty stone, and when appearing in evening dress his critics had been known to unkindly compare him to a timpani drum. And like a timpani, he had a tendency to boom, as he now boomed his remarks at our gathered Society. They were his usual. Diligence, caution, skepticism, humility ... The archeologist's virtues, as he had reminded us many times.

They were also, signally, virtues that Baxter Carswell lacked. Twice, Stapleton himself had venomously attacked the man in the pages of the Society's Proceedings, mocking his outlandish claims and his "swinish and disgusting" theories. How galling, then—and not one of us present, I'm sure, wasn't thinking it—for our president to now have to acknowledge and honor Carswell's momentous discoveries on Crete.

"Thank you, Mr. President," I heard a voice say, and I retrieved my attention from the foggy distraction into which I had fallen. "I know how hateful tonight's ceremony must be for you, and so I am immensely gratified to be attending it."

It was Carswell speaking. He had risen to his feet, and it struck me what a little man he was. Not only morally—an audible murmur of disapprobation was rippling through the assembled members—but physically. Even standing, the crown of his head barely o'er-topped that of our seated president. Unpleasant, too, was his accent, for he spoke through his nose in a kind of quack.

"—the magnitude," he was saying, "nay, without conceit I assert, the epochal profundity of the revolution that will attend the resurrection of that city we have gathered tonight to mark—"

"I say, he's really laying it on, isn't he?" murmured my neighbor, a man named Wilditch, into my ear. "Well, the man has a right to preen, I suppose."

Indeed. There was not only the extraordinary find itself—the one that had forced the Society to recognize Carswell and the truth of his theories—but the extraordinary circumstances that had confirmed them.

It is every archeologist's dream, I suppose, to find a "lost civilization." Few would dare conjecture them, however, and none save Carswell would have so brazenly asserted the existence of a drowned city off the coast of Crete—the lost outpost, he insisted, of an antediluvian culture wiped from the Earth ere the founding of Atlantis. Under its cyclopean walls and within the tentacular labyrinths of its temples and palaces, he had written, prospered things more like unto gods than men. Or unto demons, he had cryptically added in a footnote, if one's morality is of the conventionally cramped sort.

No, these were not the sort of cautious and conservative conjectures Stapleton liked to commend. But then, Carswell was an amateur, a man known to "dabble in the dregs of metaphysics and moonshine," as Stapleton had described him in one of his (less vituperative) passages.

Carswell was describing the city now, I noted as I again began to attend his remarks. It was hard to concentrate on him. It was not only his accents and manners that were odious. His very claims were repugnant.

He was, of course, entitled to describe for us the ruined city that had lunged so spectacularly to the surface of the Aegean—exactly where he had claimed it existed—as the result of a violent undersea tremor. And if one forgave the pugnacity of the image, one might even applaud his descriptions of its "sturdy bones still dressed in the glistening, oozing muds of the deep." But—

Come, come, I thought with some irritation. You still have not established that it was Dagon they worshipped. And even if you mean it as a poetic turn of phrase, it is meretricious to credit the earthquake to the agency of some god or other.

"Even now," Carswell was wheezing as the choler in our president's face deepened, "my men are obliviously scooping away the slime and silt of centuries from out the avenue that leads to the pythonic temple of dread Dagon, before whose idol—whose immensity still fails but to impotently gesture at the awful exaltation of the deity it represents—but before which, as I was saying, the frenzied divines of his cult performed such mighty oblations as caused the very stars to wobble. Even now," he piped as he flushed, and his glittering eye roved the room, "yea, even as we speak, the very lineaments of eternity are bending into alignments monstrous, to parallel that roadway out of Deepest Time, and down them like ladders shall descend—!"

"Yes, thank you, Mr. Carswell," interrupted the president. He stood and politely clapped some three or four times, nodding at the assembly to join in. (We didn't.) "We shall be delighted to hear all about it when—"

"The Earth's very foundations shall shatter! The continents shall reel!"

"Yes, yes, the earthquake. Certainly," murmured Stapleton as he laid a great hand on his guest-of-honor's shoulder and shoved him back down into his seat, "we should all of us pray for such happy accidents as that which helped confirm your—"

"Accident!" shrieked Carswell, and even at a remove I could see the whites of his rolling eyes. "Was it by 'accident' that I drenched the Altar of Meleck-Taos in gore, to slake the long-parched gullet of Dagon's Herald?"

The Altar of Meleck-Taos? I thought I knew the name. I turned to my neighbor Wilditch, to confirm that that was the identification given by Carswell to some immense sarcophagus or other he had found buried twenty feet beneath the foundations of the palace at Knossos.

He forestalled me with a question and frown of his own. "Gore?" he asked. "Wasn't there some ghastly business back there on Crete, nearly got him kicked off the island? Some local girl gone missing?"

The murmur of the company had risen, but even over it I could hear snatches from Carswell. "By bribery, the keys to this hall!" — "Sigils written in invisible blood!" — "Tentacles and beaks and the baleful eye of Dagan Takala!" — "The wall behind this dais!" Spittle showed on his lips as two burly waiters, at a signal from Stapleton, seized him by the arms.

"Yes, spare me a day, a week, a month!" he laughed as he was dragged away. "You are but the first! Gladly did I seek to mingle with you tonight, that I might delight at the whistling music your bones will make after the marrow is sucked from out them by the gale-force hurricanes that shall envelope your blaspheming company! But to the maddened squeals of humanity's writhing mass shall I yet dance and cut myself before the—!"

Twisting like a thing of coiled wires, he was carried bodily from the banqueting hall.

"I must apologize to you all," said our president as he patted his forehead with a white handkerchief, "for the, er, regrettable behavior just shown by our distinguished guest." He said the words with undisguised contempt. "Even a madman may have lucid intervals," he went on, "but I think we can all congratulate our fortune in being able to remove the madman whilst retaining, for our own delectation, the antique remnants he—"

He got no further, and few had attended him even that far before he broke off as those of us seated before the dais began to stand and gasp and point at the wall behind him, in which there had opened what to all appearances was a swirling vortex of smoke and mist.

That in itself was unaccountably strange. But I could not help but believe I comprehended within it certain uncanny shapes. Was that not a black and baleful eye glittering from out its center? Where those not beaks that orbited, darting and biting as they dipped in and out from between the vortex's whirling arms, which were themselves like tentacles tipped with cruel pincers?

I had but a moment to take the nightmare in before the lights of the hall blinked out, and a roaring gale lifted and sucked me into it.

Prompt: Use "gale-force," "dread," "pincers," "swirling," and "toast" in the story.

0 notes