Text

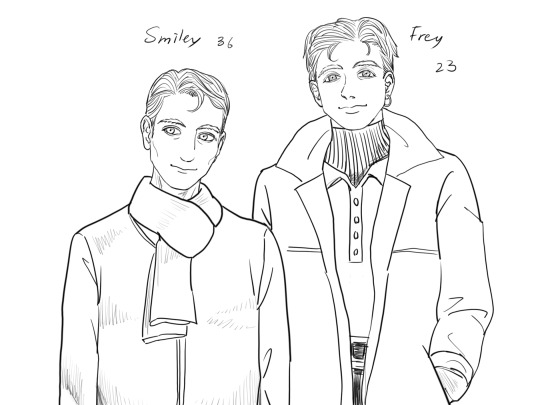

George and Dieter

This is not real George…He may be the Alec Guinness' kind of George(?)

0 notes

Text

Bill is a BEAGLE

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

my friend says this couple sinfully looks like father and son

0 notes

Text

The great author recalls Smiley’s origins in one of his last pieces of writing, a new introduction to Call for the Dead.

I wrote Call for the Dead, my first novel, because I had been boiling to write for 20 years but had never quite had the prompt. I had done book illustrations, I had written bad poetry and one or two stories, and produced a couple of amateur plays, and become a reasonable hand at caricatures. In a bookless household, I had managed to acquire some sort of taste for books, largely because of a master at one of my early schools who read aloud to us beautifully from Conan Doyle and GK Chesterton. At 16, having fled my English public school, I took a huge sidestep into German language and literature and ended up teaching them at Eton, with the result that English letters always played second fiddle. It took a lurch from Eton into the intelligence community to get me writing Call for the Dead, and the prompt came from John Bingham, novelist, spy and colleague.

In MI5 the standard of report writing was very high indeed. Registry and senior officers were all pedants and descended on you like eagles if they spotted a sloppy sentence or an unsubstantiated claim: “Too fluffy. Can you actually demonstrate this? If this is hearsay, kindly say so clearly,” ran the marginal comments in different handwritings as your report came whistling back to you from the top floor. It was my first experience of having to battle for every sentence I wrote as if it had to stand up in court.

The agent-running section to which I was eventually attached was dominated by two figures, both men: Maxwell Knight, naturalist, broadcaster and the subject of at least two published biographies, and Bingham. Knight, allegedly of the far right, though I never heard him on politics, was by the time I knew him tolerated only on account of the agents he had recruited long ago and that were still beholden to him. He was a big, unwashed, silvery, boy scout of a man, of great charm and idiosyncratic habits that included bringing ailing small animals such as gerbils into the office in his jacket pocket. Bingham could scarcely have been more different.

Everything about Knight suggested that he be enjoyed with caution, but John was approachable, unassuming, quietly spoken and a kindly shepherd and confessor to his agents, mostly women. He was also a needle-sharp intelligence officer of great experience, as I had good reason to learn when one of my agents was blown and I needed his urgent advice on how to limit the damage. And John of necessity did much of his work in the evenings, when his agents returned home from their high-wire acts needing his consolation and wisdom and a large gin.

So by day, when he wasn’t writing a report, John was writing a novel. He had written quite a few by then, thrillers, all published by Gollancz and well received. I don’t remember that we ever talked about the process of writing. John, once a journalist, didn’t see himself as a literary man, just a thorough writer doing a job. The one piece of advice I remember him giving me was to stick a postcard with £100 written on it above my desk and look at it every time I thought of giving up. But far more inspiring than anything he could have said was the simple act of him sitting five yards from me day after day at his desk with his head down and a hangover, writing himself a novel on lined paper. And I suppose, at the most primitive level, I decided that if he could do that, I could.

I lived in Great Missenden in those days and commuted to Marylebone station, then walked or took the bus to Curzon Street. The train journey was an hour plus, so I wrote in small notebooks supplied, I am ashamed to say, by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. I just wrote. And the first person who came to mind was the man who got me going: John Bingham, one of the meek who do not inherit the earth.

But no real character in my experience is drawn directly from life, and for George Smiley I needed a lot of things that John simply hadn’t got and didn’t wish to have: an obsession with German literature (although he spoke decent German), a miserable private life, a sense of being strapped to the secret treadmill and not knowing how to get off it, and most importantly serious moral questions about the work I was doing. John was, to say the least, a nationalist, and doubts of that sort were simply not his thing, particularly when his every evening was spent buoying up women agents who were, in their estimation and his, sacrificing their private lives for England. So where to turn?

Well, my own life had been pretty well supplied with moral doubt, not least by my father, a conman on the run from the law. But I needed more stately concerns for George Smiley, bred in me in part by the unsparing plays of Schiller, Lessing and Büchner and the anguished cries of 17th-century Germany.

But Smiley is not at heart an academic. In the beginning was not the word but the deed, Goethe tells us through the agency of his Faust, and Smiley refuses to shirk from action where he believes in the rightness of his cause. And so it seems to me now, with the luxury of hindsight, that for Smiley’s conflicted inner life I resorted to my beloved mentor, Dr Vivian Green, by then rector of Lincoln College, Oxford: scholar, administrator, closet iconoclast and Anglican priest whose institutional faith over time gave way to a universal humanism. I don’t know any more whether you will find the seeds of all this theorising in my first stab at George Smiley, but I do. We have grown up together, changed and matured together, and seen his likeness exquisitely portrayed by two great actors, Alec Guinness and Gary Oldman. But for me he’s still the same soul-searching secret sharer that I wrote about in little notebooks on the rattly commuter train from Great Missenden to Marylebone.

Extracted from Call for the Dead by John le Carré; the 60th anniversary edition is published by Penguin Classics on Thursday.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

what have I done, Mundt? You don't like me.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Podcast Recommendation: Spybrary

Description: Spybrary is a spy podcast for fans of spy books and spy movies. We interview spy authors, intelligence experts and spy fans!

Episode 155: Collecting John le Carré novels

Episode 131: RIP John le Carré

Episode 119: Agent Running in the Field (brush pass review)

Episode 95: A Small Town in Germany (brush pass review)

Episode 93: Agent Running in the Field (round table discussion)

Episode 32: John le Carré and the Cold War with Toby Manning

Episode 18: A Legacy of Spies

Episode 17: An Evening with John le Carré (field report)

Episode 6: George Smiley and Call for the Dead

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can we talk about the quiet, tragic eroticism of Magnus and Axel's friendship in John Le Carré's A Perfect Spy?

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Church of Forty Martyrs, Pereslavl-Zalessky

Photo: Alexander Lukin

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mundt and Dieter, but both are girls

0 notes