Text

Mom and sons, Detroit, 1942, photo by Todd Webb.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert Ayler Quintet outside of the famous club Slugs, Avenue A in NYC, May, 1966. Left to right Donald Ayler, Albert Ayler, Ron Shannon Jackson, Lewis Worrell and Michel Samson.

5 notes

·

View notes

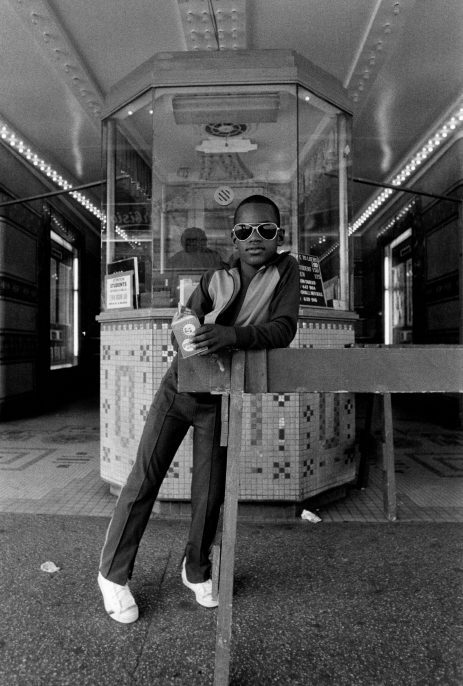

Photo

Young man in front of Lowe’s movie theater in Harlem, 1976. Photo by Dawoud Bey

193 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maxwell Street Flea Market, Chicago, Illinois, September 9, 1955

973 notes

·

View notes

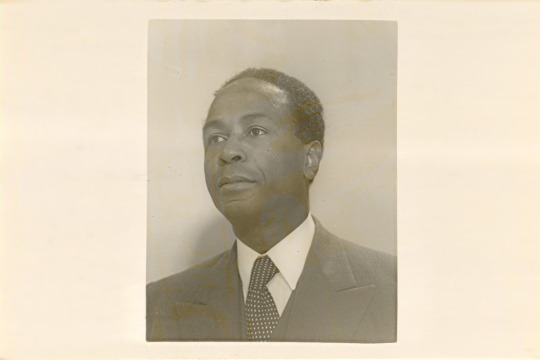

Photo

A journalist, radical activist, and theoretician, George Padmore did more than perhaps any other single individual to shape the theory and discourse of Pan-African anti-imperialism in the first half of the twentieth century.

Born Malcolm Nurse in Trinidad in 1901, Padmore moved to the United States in 1925 to study at Fisk and Howard Universities. In 1928 he dropped out of Howard’s law school and joined the American Communist Party. Quickly rising in Party ranks as an expert on race and imperialism, Padmore moved to Moscow, USSR in 1929 to head the Comintern’s International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers and to edit the Negro Worker. In 1931 he published the influential pamphlet, The Life and Struggles of Negro Toilers. In 1933 the Comintern suspended publication of the Negro Worker and disbanded the Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers, prompting Padmore to split acrimoniously with the Party. In subsequent years Padmore would become a fervent anti-Communist, denouncing the Comintern’s alleged manipulation of black freedom struggles in his 1956 book Pan-Africanism or Communism? However, throughout his life, he continued to unite with activists and trade unionists on the radical left around the issue of anti-colonialism.

Padmore settled in London, UK in 1936. There he helped foster a radical milieu of Pan-Africanist intellectuals that included Padmore’s childhood friend, the Trotskyist theorist C.L.R. James. In 1936 Padmore published How Britain Rules Africa, followed a year later by Africa and World Peace. Along with I.T.A. Wallace-Johnson, Padmore and James founded the International African Service Bureau in 1937. Padmore guided the bureau through the late 1930s and early 1940s until in merged into the Pan-African Federation in 1944. He was a principal organizer of the Manchester Pan-African Congress in 1945, which helped lay the foundation for postwar African colonial liberation movements. Throughout this period Padmore’s articles and essays were printed regularly in the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, and The Crisis, as well as in newspapers throughout Britain, West Africa, and the Caribbean. Padmore’s international journalism and other writings linked African American struggles with liberation movements in Africa and with African Diaspora peoples around the world and thus had a profound effect on the contours of black political thought.

George Padmore spent his final years in newly independent Ghana as an advisor and mentor to Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah. He died in London in 1959.”

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cuban President Fidel Castro, accompanied by President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, discusses a point with a Cuban worker during visit to a Cuban-aided agriculture school. Castro apologized to Tanzania for not being able to provide that African nation with more aid, saying his country's resources are tied up elsewhere in Africa, namely Angola, helping the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) in their fight for independence from Portugal.

30 notes

·

View notes

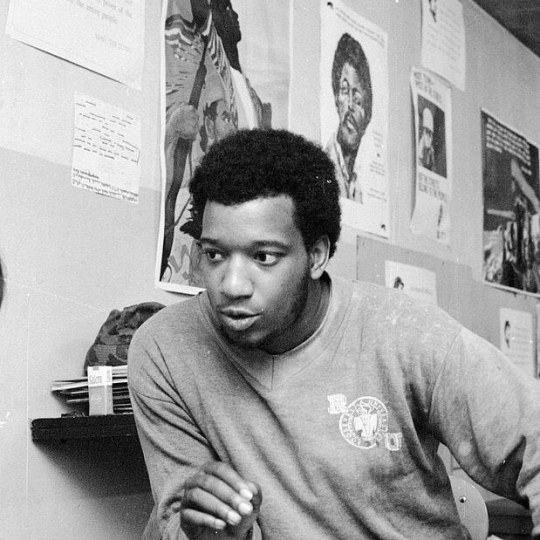

Photo

The police moved in before dawn.

Their target was a first-floor apartment on Chicago’s West Side. Among those inside were two top leaders of the Illinois Black Panther Party — chairman Fred Hampton and Mark Clark.

Officers assigned to Cook County State’s Attorney Edward V. Hanrahan approached the dwelling with a warrant authorizing a search for illegal weapons. Gunfire — police claimed they faced a barrage from inside the apartment — erupted shortly after the raid began at 4:45 a.m.

When the shooting stopped, Hampton, 21, and Clark, 22, were dead. Four other Panthers and two police officers were wounded. Seven Panthers in the residence were charged with attempted murder.

The Dec. 4, 1969, confrontation at 2337 W. Monroe St. ended quickly, but the controversy over what exactly happened — fought over in the pages of the city’s newspapers, on local TV and in the courts — reverberated for years to come. (Photo below: Chicago police remove the body of Fred Hampton, leader of the Illinois Black Panther Party, who was slain in a gun battle with police on Chicago’s West Side on Dec. 4, 1969.)

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Amiri Baraka (winner of the JJA's 2012 Lifetime Achievement in Jazz Journalism Award) with Bertha Hope at the Jazz Journalists Association's 2013 Jazz Awards party at the Blue Note Jazz Club in New York City, June 19, 2013. Photo by Fran Kaufman.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ella Fitzgerald, her assistant. Georgiana Henry, Illinois Jacquet, and Dizzy Gillespie, all dressed to the nines in Houston Police Department holding cell.

Ella Fitzgerald with her assistant in a Houston PD holding cell after she and fellow great Dizzy Gillespie were arrested for “throwing dice” in Fitzgerald’s dressing room at the Houston Music Hall, 1955.

Fitzgerald and Gillespie were performing in Houston at the Music Hall as part of Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic tour, which included other jazz legends like Buddy Rich, Oscar Peterson, Gene Krupa and Lester Young. Saxophonist Jacquet — also on the bill — was the prime mover in bringing the show to Houston and making sure the concert (which featured both black and white musicians) would be integrated.

Two shows were scheduled that night. The raid took place before the end of the first concert.

According to the Houston Chronicle:

Vice squad officers said three of the five — Dizzie Gillespie, Illinois Jacquet and Georgiana Henry — were actually crooning to the bones when police walked into Ella Fitzgerald’s dressing room back-stage at the Music Hall.

Miss Fitzgerald and show producer Norman Granz were “just present” in the back-stage dressing room while the jazz show was going on in the Music Hall, the officers said.

However, all were taken to the police station and charged. They posted $10 bonds.

The Houston Post said Fitzgerald dabbed tears from her eyes as she was being booked.

“I have nothing to say,” she told reporters. “What is there to say? I was only having a piece of pie and a cup of coffee.”

The Post continued:

Sgt. W.A. Scotton said saxophonist Jacquet had the dice in his hand as the troop of officers walked in. The troop confiscated the dice and $185 in cash. Then they agreed to wait until the first show was over before taking the performers to the police station.

Mr. Jacquet, the saxophone man, was the most nonchalant of those arrested. He told reporters his name was Louis Armstrong.

The group didn’t stay at the police station for long. In fact, they made it back in time for the second show, leaving audiences unaware of what had taken place.

Of course, one finds it highly suspicious that vice officers would bust the five of them on a night meant to show how smoothly Houston audiences could integrate. The vice officers weren’t the only officers at the concert as eight other uniformed officers were hired to work security that night. In Gillespie’s autobiography, Granz says one of the vice officers even threatened him during the raid after he accused the officer of trying to plant drugs in a bathroom at the Music Hall.

The next day, police Chief Jack Heard said officers were probably a little overzealous in going after the performers.

“We want to enforce the law but common sense should apply,” he told the Post.

The charges were eventually dismissed.

96 notes

·

View notes

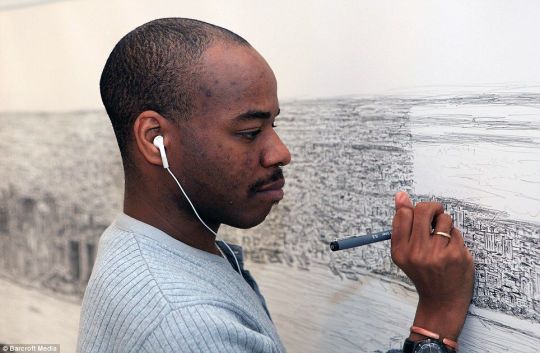

Photo

This astonishing 18ft drawing of the world’s most famous skyline was created by autistic artist Stephen Wiltshire after he spent just 20 minutes in a helicopter gazing at the panorama.The unbelievably intricate picture was drawn at Brooklyn’s prestigious Pratt Institute from Stephen’s memory, with details of every building sketched in to scale.Landmarks including the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building can be seen towering above smaller buildings after just three days in his spellbinding creation.Listening intently to his ipod throughout the artistic process - because music helps him - London-born Stephen uses only graphic pens as he commits his photographic memory to the high-grade paper.Invited by top U.S. television network CBS to display his talents to the American public in a new screen appearance this week, Stephen has dumbfounded art lovers around the globe with sketches of Tokyo, Rome and Hong Kong.‘Stephen sketches his layout in pencil first and then scales it within the border, first adding in landmarks before filling out in more intricate detail,’ said Iliana Taliotis, who works with Stephen and his family.‘He works methodically in short sharp bursts and is even being put on webcam by CBS as he puts his art to paper.’ On his third visit to New York, this is Stephen's first panorama of the world's most iconic cityscape.‘Stephen feels this is his spiritual home,’ said Iliana.‘There are many similarities between his home, London, and New York that he can relate to. ‘The only difference is that everything is on a bigger scale and with taller, more modern buildings. ‘Cities have always been his passion, and he is drawn to cosmopolitan lifestyles.’ Diagnosed with autistism at an early age, Stephen's talent for drawing emerged as a way of expressing himself.Using his drawing's to help him learn and encouraged by his family, Stephen created a series of 26 coded pictures to help him speak, all of which corresponded to a letter in the alphabet.Going through up to 12 pens during his sketches which can take a week to finish, Stephen also draws heavily on music which he carries everywhere.He listens to everything through the 70s, 80s, and 90s, including blues, soul, funk, Motown, pop, Back Street Boys, All Saints and even New Kids on the Block.He always listens to music while he works,’ said Iliana.‘This work will encompass the five boroughs of New York, New Jersey, Ellis Island and The Statue of Liberty.‘This one is extra special and unique. ‘Due to his personal love of New York it contains far more detail and the perspective of the panorama is much more in-depth, giving a more realistic, 3-D view of the city.’In May 2005, Stephen produced his longest ever panoramic memory drawing of Tokyo on a 52-foot canvas within seven days following a short helicopter ride over the city. Since then he has drawn Rome, Hong Kong, Frankfurt, Madrid, Dubai, Jerusalem and London on giant canvasses. When Wiltshire took the helicopter ride over Rome, he drew it in such great detail that he drew the exact number of columns in the Pantheon.In 2006, Stephen Wiltshire was awarded a Member of the Order of the British Empire for services to art. He opened his permanent gallery in the Royal Opera Arcade, Pall Mall, the same year. (FROM THE DAILY MAIL REPORTER, October 29, 2009)Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/.../Autistic-artist-draws-18ft... Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

BILLY ECKSTINE’s BADASSS BAND

(l-r) Art Blakey, Tommy Potter, Budd Johnson, Junior Williams, Fats Navarro, Chips Outcalt, Billy Eckstine and Gene Ammons.

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

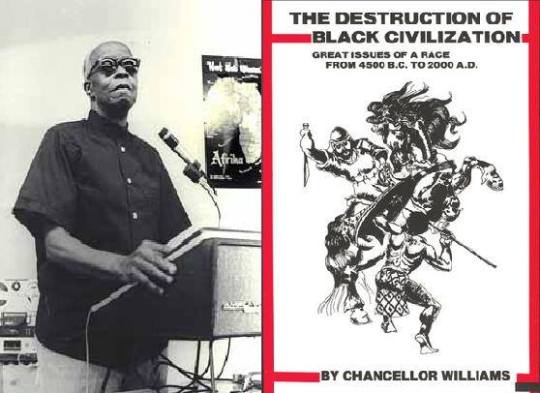

The Destruction of Black Civilization took Chancellor Williams sixteen years of research and field study to compile. The book, which was to serve as a reinterpretation of the history of the African race, was intended to be "a general rebellion against the subtle message from even the most 'liberal' white authors (and their Negro disciples): 'You belong to a race of nobodies. You have no worthwhile history to point to with pride.'" The book was written at a time when many black students, educators, and scholars were starting to piece together the connection between the way their history was taught and the way they were perceived by others and by themselves. They began to question assumptions made about their history and took it upon themselves to create a new body of historical research. The book is premised on the question: "If the Blacks were among the very first builders of civilization and their land the birthplace of civilization, what has happened to them that has left them since then, at the bottom of world society, precisely what happened? The Caucasian answer is simple and well-known: The Blacks have always been at the bottom." Williams instead contends that many elements—nature, imperialism, and stolen legacies— have aided in the destruction of the black civilization. The Destruction of Black Civilization is revelatory and revolutionary because it offers a new approach to the research, teaching, and study of African history by shifting the main focus from the history of Arabs and Europeans in Africa to the Africans themselves, offering instead "a history of blacks that is a history of blacks. Because only from history can we learn what our strengths were and, especially, in what particular aspect we are weak and vulnerable. Our history can then become at once the foundation and guiding light for united efforts in serious[ly] planning what we should be about now." It was part of the evolution of the black revolution that took place in the 1970s, as the focus shifted from politics to matters of the mind.

131 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

James Baldwin vs William F Buckley: A legendary debate from 1965

In this account, Joss Harrison looks back at one of the most powerful yet overlooked victories of the American civil rights movement.

Cambridge, 1965. James Baldwin, the renowned African American social critic, meets William Buckley, a leading conservative whose silver tongue and social class had for years masked the vile racism at the core of his philosophy. It was a seminal debate. I, for one, can think of no better way to celebrate Black History Month than a reliving of this occasion, when Baldwin dismantled his racist opponent through cool reason and unimpeachable sincerity, earning an unprecedented ovation from the practically all-white audience at the Cambridge Union in the process.

But first, we must properly introduce our protagonist. James Baldwin, born into poverty in Harlem, was by 1965 one of America’s most eloquent social critics. He wrote about race and class and sexuality and morality. He participated actively in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s while also, a gay man himself, standing up to homophobic attitudes in that movement.

And then, our antagonist. William F. Buckley Jr, born into wealth and privilege. He founded National Review, a conservative publication, in 1955, and from this pulpit helped to lay the groundworks for the American political shift rightwards that began with Barry Goldwater’s candidacy for the presidency in 1964, and peaked with the successful election and then re-election of Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. A significant man, then, clearly, but also a vile defender of segregation and white supremacy, thinly-disguised by his gentility.

And so, to the debate. Baldwin stands to speak. The motion: “The American Dream is at the Expense of the American Negro.” There are around seven hundred people in the chamber, and just two of them are black. One is Baldwin himself, another is a friend come to support him. Come twenty minutes later, that entire audience will be on its feet in an ovation unprecedented in the history of the Cambridge Union.

He sets the tone with a brilliant opener. “I find myself, not for the first time, in the position of a kind of Jeremiah.” He looks and sounds solemn, but perfectly calm.

He movingly describes the moment in a black American’s childhood when they realise that “the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you.” Black boys and girls, men and women, he says, are constantly reminded that there is no place for them in American society. They do not appear in the history books. It is as though they are “worthless” and lacking in any history or culture. The most tragic thing: they believe it, because, as Baldwin says, “I didn’t have much choice.”

Baldwin’s tone becomes withering, though, when responding to Robert Kennedy’s suggestion that it might be possible for America to have a black president in forty years. (Although that remark proved to be prescient.) Baldwin was consistently critical of John F. Kennedy’s record on civil rights while in office. This was the general attitude within the civil rights movement at the time, yet history has nonetheless remembered the Kennedy Administration has a great promoter of civil rights. Anyway, to Baldwin’s response. There is an edge to his voice now, a kind of controlled anger. “He tells us that maybe, in forty years, if you’re good, we may let you become president.” Baldwin, clearly, does not intend to be patronised.

However, as moving and emotive and sharp as the preceding critiques undoubtedly are, there is a clear pinnacle of his brilliant remarks. He says, with absolute sincerity and solemnity, and another hint of that contained anger: “I picked the cotton, and I carried it to the market, and I built the railroads, under someone else’s whip. For nothing. For nothing.” With each “I” he sharply raises his voice and you can hear his words echo around the chamber, which is, by now, completely hushed. This is the beating heart of his argument. He urges us to look below the surface layer, to challenge assumptions so deeply entrenched within ourselves that we aren’t even aware of their assistance. He removes the lens through which we look at the world and offers us his own, and through his lens there is breath-taking clarity.

When Baldwin is finished, and he has received his ovation, Buckley stands, and the difference between the two men is immediately apparent. Buckley is dressed in a full dinner suit and bow tie, as was required by the Cambridge Union. Baldwin had ignored this requirement. His mannerisms display a manifest sense of superiority, from the smirk on his face to the pointed finger he waves in the air. He speaks in a lazy drawl, as though such a facile debate requires him only to use a fraction of his capabilities.

This article will not go into depth on his arguments. They are too poisonous to merit the publicity. There are a few remarks, however, that usefully display the bankruptcy of his position. To start, he says to Baldwin that he will speak “without any reference whatever to these surrounding protections which you are used to in virtue of the fact you are a Negro.” The accusation is as clear as it is ignorant: that far from being discriminated against on account of the colour of their skin, African Americans use it to make themselves immune to reproach.

It is perhaps a sign of his desperation that Buckley resorts to personal attacks on his opponent. He calls Baldwin a “posturing hero”, worthy of “contempt”. Bizarrely, he even accuses Baldwin of adopting an English accent to ingratiate himself to the audience. (This is demonstrably false, and is a particularly ironic accusation given that Buckley himself was well-known for speaking in a transatlantic tone.)

He moves on to demonstrate his complete ignorance of the problems faced by black Americans in society. Bristling at Baldwin’s claim that the American economy was built by the unremunerated labour of black people, Buckley cries: “My great grandparents worked too!” Contemptible. He also claims that African Americans should be grateful for the society in which they live, because they are better off than the vast majority of the world’s population just by dint of being Americans. He cannot believe the cheek, the nerve! of black Americans to complain about injustice when they should, in fact, be grateful for the privilege of living in ‘the greatest country in the world’.

Throughout Buckley’s remarks, the camera regularly switches to Baldwin. His eyebrows are raised and his eyes wide. He is a picture of calm. As Buckley swings at him, again and again, and each time fails to land a blow, Baldwin’s face displays not anger, not distaste, but pity.

The Union voted by a margin of 544 to 164 in favour of Baldwin, a vast majority of 380 votes. But in truth, this is irrelevant. Baldwin didn’t beat his opponent because the Cambridge Union decreed it so. He won by the power of his argument. Against such an intellect, such a debater, such a deliverer of moral clarity, the vile segregationist never stood a chance.

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

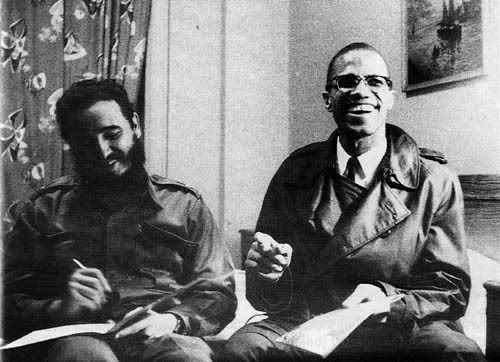

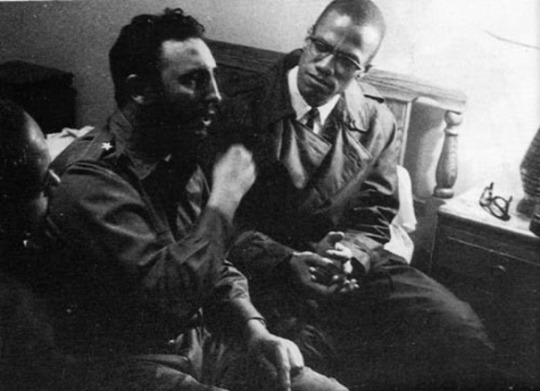

Here are the results of a legendary meeting that way it was reported, we start with The Militant reported that: On September 19th, 1960 Fidel Castro traveled to the United States to address the United Nations, General Assembly.

. . Castro did not receive a warm welcome from the U.S. government during his visit to New York City in 1960.

The Cuban delegation moved to Harlem after being kicked out of the Shelburne Hotel amid a racist slander campaign in the press that included baseless charges – repeated to this day by the Associated Press – of plucking live chickens at the hotel.

I always remember when I met with Malcolm X at the Hotel Theresa (which was managed by the father of Harlemite Ron Brown’s, who was a former United States Secretary of Commerce under President Bill Clinton), because he was the one who gave us support and made it possible for us to be accommodated there.

We had two choices: one was the patio in the United Nations; when I told this to the Secretary-General he was horrified at the thought of a delegation camping in tents there; and then we received Malcolm X’s offer, he had talked to one of our comrades, and I said: “That is the place, Hotel Theresa.” And there we went. – Fidel Castro

Ralph Mathews of the New York Citizen Call in 1960, reported that: To see Premier Fidel Castro after his arrival at Harlem’sHotel Theresa meant getting past a small army of New York City policemen guarding the building, past security officers, U.S. and Cuban. But one hour after the Cuban leader’s arrival, Jimmy Booker of the Amsterdam News, photographer Carl Nesfield, and myself were huddled in the stormy petrel of the Caribbean’s room listening to him trade ideas with Muslim leader Malcolm X.

Harlem was a more gracious host to Castro than high-society Midtown had been. Crowds gathered outside the Hotel Theresa, as the honored guest held court in his room. He received official visits from foreign leaders—like Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru—as well as American civil rights figures, such as Malcolm X, New York NAACP President Joseph Overton, and, according to some reports, Jackie Robinson. Juan Almeida Bosque, the Afro-Cuban army commandante, became an instant icon, with throngs of people trailing behind him on the street.

Dr. Castro did not want to be bothered with reporters from the daily newspapers, but he did consent to see two representatives from the Negro press. . .

We followed Malcolm and his aides, Joseph and John X, down the ninth-floor corridor. It was lined with photographers disgruntled because they had no glimpse of the bearded Castro, with writers vexed because security men kept pushing them back.

We brushed by them and, one by one were admitted to Dr. Castro’s suite. He rose and shook hands with each one of us in turn. He seemed in a fine mood. The rousing Harlem welcome still seemed to ring in his ears. . .

After introductions, he sat on the edge of the bed, bade Malcolm X sit beside him, and spoke in his curious brand of broken English. His first words were lost to us assembled around him. But Malcolm heard him and answered: “Downtown for you it was ice. Uptown it is warm.” The premier smiled appreciatively. “Aahh yes. We feel here very warm.”

The New Republic reports that the local Amsterdam News at the time, James L. Hicks commented that, “Though many Harlemites are far too smart to admit it publicly, Castro’s move to the Theresa and Khrushchev’s decision to visit him gave the Negroes of Harlem one of the biggest ‘lifts’ they have had in the cold racial war with the white man.”

Then the Muslim leader, ever a militant, said, “I think you will find the people in Harlem are not so addicted to the propaganda they put out downtown.”

In halting English, Dr. Castro said, “I admire this. I have seen how it is possible for propaganda to make changes in people. Your people live here and they are faced with this propaganda all the time and yet they understand. This is very interesting.”

“There are twenty million of us,” said Malcolm X, “and we always understand.” . . .

On his troubles with the Hotel Shelburne, Dr. Castro said: “They have our money. Fourteen thousand dollars. They didn’t want us to come here. When they knew we were coming here, they wanted to come along.” (He did not clarify who “they” was in this instance.) . . .

On U.S.-Cuban relations: In answer to Malcolm’s statement that “As long as Uncle Sam is against you, you know you’re a good man,” Dr. Castro replied, “Not Uncle Sam, but those here who control magazines, newspapers…”

Dr. Castro tapered the conversation off with an attempted quote of Lincoln. “You can fool some of the people some of the time,…” but his English faltered and he threw up his hands as if to say, “You know what I mean.”

https://youtu.be/UAcgbsPgCbo

Credits: 1) Via source. 2-6) Malcolm X and Fidel Castro. 7) Fidel Castro and Hotel Theresa workers Photographs via Source.8) Video via source. The Militant.

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

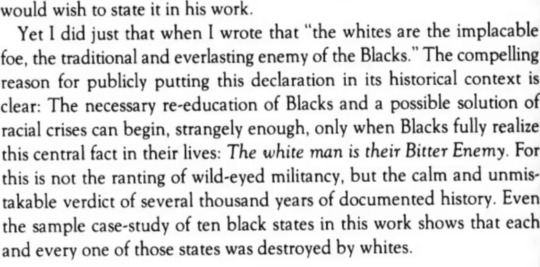

excerpts from the destruction of black civilization

each one teach one simple #math

4 paragraphs that mean everything to Africans in America

1K notes

·

View notes