Text

Whelp, later days peeps.

I’m logging off. Maybe one day I’ll come back to this crazy land called tumblr, but only when it pulls it’s head out of its ass so message me on my twitter when that happens.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Starting December 17th I’ll be off tumblr.

I don’t really post NSFW stuff but I support a lot of my artist friends who do.

I’m sex worker positive and I believe that pornography is a form of art and human expression and that there is nothing wrong with sex and we shouldn’t criminalize it.

I think there are many ways tumblr could be dealing with bots and child porn and this is not it, they could have cracked down YEARS AGO on a lot of negative shit and they have consistently chosen NOT TO.

I’m @Ramen_Quest on twitter, you can find me on youtube as well, I’ll miss this crazy place an all you crazy folks so hopefully we can still keep in touch, tweet at me when you find a new place to host your art.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

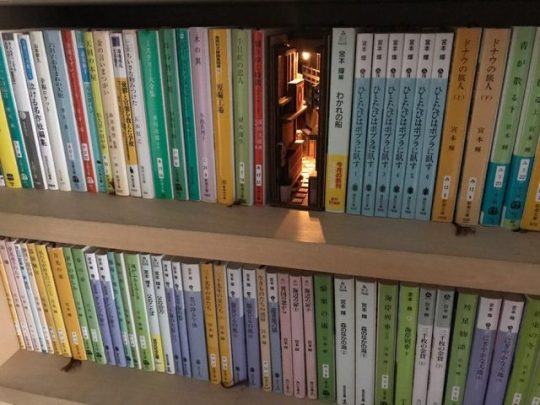

A Japanese artist who goes by monde has made a series of wooden bookend dioramas that replicate the back alleys of his hometown of Tokyo.

Sources: x x

@stick-arms @lunaticobscurity

83K notes

·

View notes

Text

Shinto 101

Hello!

As someone who grew up with Shinto (along with Buddhism and Catholicism) and also currently a miko at my local shrine (of the Konkokyo branch) I figured I would like to give a basic intro to Shinto most online sources (Even books) are misinformed about or lack, or misunderstood in a Western setting.

Any other Shintoists/Konkos/etc. that would like to contribute to this guide, please feel free and reblog to your heart’s content! :)

——

What is Shinto? Am I allowed to join? Are non-Japanese people who worship native Japanese gods (*kami) still considered Shinto?

Shinto is not really a religion, but a system of Japanese pagan worship of the local nature/worldly deities. Basically just a system to honour the spirits of Japan and the world. People built shrines for these spirits/gods (called kami) and left offerings for blessings. Eventually, shamans began to communicate with the kami and learned more about them, and are recognized as the current kami of today.

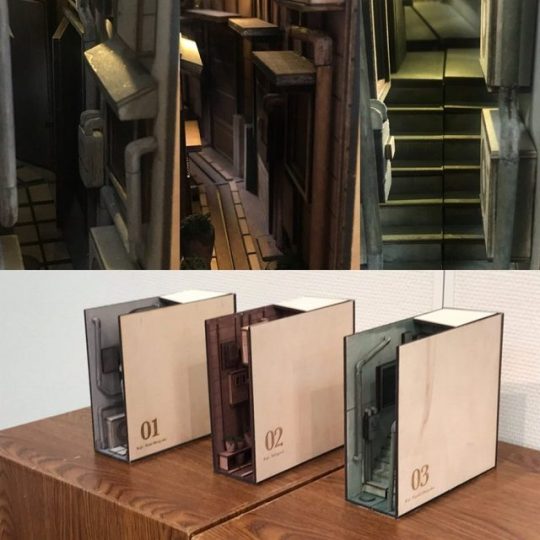

Presently, Shinto is majority traditional than spiritual in Japan. Many people only go to shrines out of tradition (Festivals/Matsuri, New Years, Weddings, etc) , an excursion, or a “good luck wish” place (Asking to pass an exam, asking for a baby, etc). Many people, even the priests or mikos at some shrines, aren’t even sure the god of that shrine really exists. But that’s not the point. The point is just to continue on tradition and go by feeling and energies of that place. Indeed, shrines are also good for the soul to visit.

However many spiritual people inside and outside of Japan still exist. These are shamans and people who can hear and feel the gods and act as their caretakers and devotees.

YOU ARE ALLOWED TO BE SHINTO! ANYONE IS! :) Even if you don’t have a drop of Japanese blood in you or you’ve never even been to Japan!!!!

(Rev. Koichi Barrish, of Tsubaki America Jinja and visitors)

I cannot stress this enough!!!!! Many materials on Shinto are ruined by the Western understanding of Shinto from World War II era, namely Kokka Shinto. This Shinto was Japanese propaganda to exclude foreigners. PLEASE understand, this is not true Shinto

Shinto is simply the worship/reverement and appreciation of nature and/or the kami of Japan and giving them an altar/shrine and (optional) offerings. Even if you just feel close to a kami and adore them, or just feel the vibrations of nature and adore nature, you are already (or can be considered) a Shintoist! It’s as simple as that :) Many people are Shinto without realizing it.

Are only men allowed to be priests? What are miko?

Men and women are allowed to be priests/priestess. They can also get married and have children! Their role is to command the rituals and maintenance of the shrine. It gets a little more complicated though.

Every shrine has a head priest. Their role is to set service dates, give special services, process requests and paperwork, prepare offerings, and overall caretake for the kami and shrine.

Then, there’s associate priests who assist with these duties, and also with administrative work, such as treasurer or secretary. Sometimes in smaller shrines, these are left to a certain group of trusted laypeople to work as volunteers.

After that, there’s the miko (me!). In olden days, these were women who ranked higher than the priest and could channel the gods and either be possessed (kamigakari) by, or be the mediator between god and man and deliver oracles.

I do those things now; but many miko do not. The role of a miko in modern times is simply to help clean up the inside/outside of the shrine, help serve naorai lunch and tea (lunch made from offerings), perform Kagura/Kibimai/Miko Mai sacred shrine dance offering (what I do), or sometimes even play the instruments in dance like koto or flute. (what my friends do). They also watch over omamori and ofuda that are for sale, or assist with events.

Also, as a side note, one thing Western writers write that bothers me: Virginial miko. Mikos are NOT required to be virgins, and never have. Ame-no-Uzume is the patron deity of all miko, as her dance is the origin of Kagura among other things. Ame-no-Uzume is also the goddess of revelry and sensuality, including sex. Sex is seen as a divine act and also enables one’s spiritual senses to heighten. A miko that has to be a virgin doesn’t make sense.

In the end, it doesn’t matter! Mikos were virgins, some weren’t. In fact some are even married with children. (There’s no age limit either) What matters is their heart is devoted to the kami of their shrine, and has sincere intentions to caretake for that kami.

How many kami are there? What exactly is a kami? Why are there shrines to kami?

There is an infinite number of kami, for every little thing in the world, even man-made things. Even including yourself and your body, you are a part of kami. Some kami are more powerful in nature (have more energy) than other kami, simply because they are more ancient, a spirit of a powerful physical thing (like Amaterasu and the sun) or they receive a lot of devotion and prayer (and thus, strength and support).

A kami is not necessarily a god/deity, though commonly kami = god/deity. However, kami also can mean the spirit of a thing, or the energy surrounding a place, like the kami of a tree, is a spirit of a tree, and the kami of the sun, is the goddess of the sun Amaterasu. Kami is a complex word, but in essence the best way to understand it is the context in which it’s referred to.

“The kami of the tree seems happy” - the spirit of the tree is happy

“The kami of the sun is shining brightly” - the goddess of the sun is shining brightly

“Kami are everywhere” - the gods/spirits are everywhere

Now, there’s titles to add onto the word “kami” - O-Kami, means “Great God” usually reserved for only powerful gods like Amaterasu-Omikami (greatest goddess) or Sarutahiko-no-Okami (Great god Sarutahiko). There’s also Kami-sama, which can either refer to a general deity, or, in my case, to Tenchi Kane no Kami, the deity that is the spirit of the universe itself. Thus, this Kami encompasses all the other kami as part of it. So it’s Kami-sama!

We have shrines for kami not because they really “enshrine” in the sense the kami is cooped up in their shrine and cannot leave lol. But they act as “power spots”. In the sense the kami’s essence is felt very powerful at shrines. And/or, the kami’s spirit can travel or be split to reside in the area of these shrines. Essentially, shrines are like wi-fi hotspots, the place where you’ll feel the most connection to the kami enshrined there. Home shrines/altars work the same way. The kami’s presence will be there. Usually this is done through the power of ofuda (tablets which contain the kami’s essence or have the kami’s name which draws them towards it)

(torii - that big red gate, acts as a symbol to a more spiritual area)

Do ofuda/omamori or other shrine paraphernalia really “expire”?

This is a bit controversial, so bear with me, and it’s a little secret information from a miko. They do not lose their power with time. However, they are good to keep buying to support the shrine.

The reason however shrines say to burn and renew them each year is not for only donations. Over time, the power does not lessen, but grows more powerful. If the owner is a layperson than does not know how to purify or bless, this ofuda/omamori can absorb other energies, and often can become a Tsukumogami (a youkai/spirit of an object) and loses the essence of the kami you want to worship. Therefore, you should only keep using an old ofuda/omamori if you yearly purify/bless it with the essence of it’s original kami. (I will explain in another post) If not, please just buy new ones! ;w;

How do I begin practicing Shinto or worshipping a kami? What do I need to do? Any special ritual? Do I need to go to a shrine?

Alll you need to do is feel connected to a kami, and you practice Shinto. There is no special ritual like Baptism or Buddhist vows, (well, there’s a variation, but its absolutely not a requirement). And you do not even need to a visit a shrine in your life to be Shinto.

All you need to do really is go outside and appreciate the beauty of nature. Not even that, just appreciate all you have in your home and all of your blessings. Focus on the good and positive, realize the nature of the universe, and that is practicing Shinto.

If you want to get more into it, please build or set up an altar (there are home shrines called Kamidana you can buy, but they are not necessary) And use an ofuda to attract the essence of the kami. Or even just a paper with their name, or their image. At the altar, you can leave offerings or not, but common offerings are rice, salt, water, and sake. You can leave whatever you like though, as long as you offer it with sincerity (I will go more into it on a future post)

Shrines are scarce outside of Japan, but there are a surprising number. The famous one in America is Tsubaki Jinja in Washington. Let me list a few

Tsubaki Jinja, in Granite Falls, Washington

Ki-no-Mori Jinja, in Salt Spring Island, British Columbia, Canada

Shrine to Amaterasu-Omikami on Shambhala mountain center in remote Northen Colorado

Small Inari shrine in Brooklyn Botanic Garden, New York (the National Shinto association is in New York as well)

There are also a handful of shrines in Hawaii! Taken from wiki

”

Daijingu Temple of Hawaii

Hawaii Ishizuchi Jinja

Hawaii Kotohira Jinsha - Hawaii Dazaifu Tenmangu

Hilo Daijingu

Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

Māʻalaea Ebisu Jinsha

Maui Jinsha Mission”

There are also many Konko shrines/churches (the branch I belong) all across North America, you will find a complete list here (Spans from East to West coast, across US, Canada, Hawaii, Brazil, and Korea) www.konkofaith.org*

*Note of respect: While Konkokyo has origins in and worship style of Shinto, which may be good for you in terms of spirit and comfort, it is also it’s own religion. If you visit a Konko building, please be respectful and do not assert it’s a Shinto shrine! Please have an open heart and mind :)

If you live in Europe, there’s a hokora (shrine foundation/worship hall) in the Netherlands, in Amsterdam. Konkokyo also has yearly London gatherings/services.

Hopefully this guide could help you be acquainted with Shintoism outside of Japan! If you have more questions, please feel free to ask me! There are also many great Shintoists already here on tumblr you can ask :)

16K notes

·

View notes

Photo

July 2018: Geiko Momifuku (Yamaguchi Okiya) of Pontocho performing the Kabuki Odori at the Yasaka Shrine at the end of the Gion Matsuri.

While the big final parade, the Hanagsa Junko parade, was cancelled due to extreme heat, the dances at the shrine still took place.

Gion Kobu and Miyagawacho and Pontocho and Gion Higashi participate in the parade and the dances in turns; this year, it was Pontocho’s and Gion Higashi’s turn. Pontocho’s Geiko performed the Kabuki Odori and Gion Higashi’s Maiko performed the Komachi Odori.

Source: Katsu H. on Instagram

142 notes

·

View notes

Video

There was a #capuella demonstration in #okubo this past weekend. #martialarts #japan (at Tokyo, Japan)

https://www.instagram.com/p/BoxJnKxFbXi/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=brweiymtqmi3

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

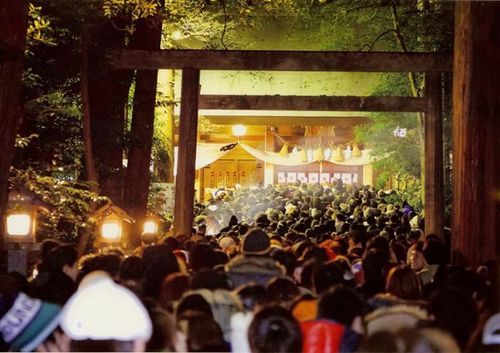

This is why I pretty much only go to women doctors. Because you know, worldwide, a female doctor had to blow every test and barrier in front of her out of the goddamn water to get to where she is. Not just meander by on her own mediocrity like most men.

But women discrimination is a myth right??

132K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=maG-K8ciOoY)

Can’t stop, Won’t stop, OH MY FEETS.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Star wars themed outfit, pairing a muted kimono with home made spaceship obi… and Darth Vader straw bag (seen on)

1K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The greatest video since “The History of Japan”

63K notes

·

View notes

Photo

#graffiti #graffitiart #edmonton #canada

https://www.instagram.com/p/BnGcHMHgCkG/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=18vcsz77moz48

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#yum #food #japan #bingsu #koreatown #shinokubo I JUST WANNA EAT THIS FOREVER.

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Higa was one of more than a dozen American soldiers of Japanese ancestry who were involved in the Battle of Okinawa, which some historians have called the “cruelest battle of the Pacific.” It was a costly battle. More than 12,000 Americans and some 95,000 Japanese–60,000 of whom were Okinawan civilians–were killed.

For Kalihi resident Takejiro Higa, the Battle of Okinawa would pit two “parents” against each other.

Higa was born in Waipahu. At the age of 2, his mother took him, his brother Warren, then 5, and 8-year-old sister Yuriko to Okinawa to meet their grandparents. His father remained in Hawaii and operated the family store. Three years later he went to Okinawa to accompany his family back to Hawaii.

Higa was 11 when his parents died within a year of each other. His grandparents, with whom he and his mother had lived, died the following year. For the next four years, he lived with an uncle.

As his 16th birthday neared, Higa began thinking seriously about returning to Hawaii. New immigration to Hawaii had been halted in 1924, and Japan had begun sending young, able-bodied men to settle in Manchuria in its efforts to control Asia militarily.

When Higa turned 16 in April 1939, he wrote to his sister in Hawaii, asking her to sponsor him back to Hawaii “before the Japanese army grab me.” “Personally, I didn’t want to go Manchuria. If I had to leave Okinawa, I’d rather go back to Hawaii where my sister and brother and other relatives were.”

That July, 14 years after leaving Hawaii as an infant, Takejiro Higa went “home.”

Less than three years later, Japan and America were at war.

In early 1943, despite reservations about his lack of proficiency in English, Higa volunteered for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. His brother volunteered, also. Warren made the cut; Takejiro didn’t.

Several months after the 442 had left for training at Camp Shelby, Higa received a letter from the War Department, informing him of its plans to organize a unit of Japanese language soldiers, the Military Intelligence Service (MIS), to serve in the Pacific warfront. Was he willing to serve?

“It put me in terrific turmoil, psychologically, because, if it’s Japanese, it’s understood I’ll be sent to the Pacific warfront,” he says. What if he came face to face with someone he knew - a relative, a classmate. “It may not happen, but it was possible,” he said.

It left him torn between his personal anxiety and his desire to serve his country. After days of soul searching, Higa decided to volunteer for the MIS. This time he made the cut.

Higa was accepted into the MIS and underwent eight months of language training at Camp Savage, where he studied not only the language, but technical and military terminology based on a Japanese Military Academy textbook. He graduated in July 1943.

At his sister’s request, Takejiro was assigned to his brother’s team, an action that required War Department approval. The practice had been banned after five brothers serving on the same cruiser were killed when it was torpedoed in the South Pacific.

“In my case, my sister wanted me to be with my brother because of my lack of proficiency in English. She felt that two brothers serving together would cover each other and help each other,” Higa explained.

Approval was granted.

The brothers returned to Hawaii in the summer of 1944 and were assigned to the 96th Infantry Division. After two weeks of jungle training on Oahu, their jobs as soldiers officially began when the 96th was sent overseas.

En route to their destination, Yap Island, they learned that the island had been secured. So the 96th was diverted to Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters in New Guinea and then dispatched to Leyte lsland in the Philippines.

The captain said he heard that Higa had lived in Okinawa for many years. In what area, he asked. Higa pointed to the general area of his grandfather’s village in Nakagusuku.

Next he pulled out an aerial photo of Okinawa’s capital, Naha City. “I couldn’t recognize it at first,” Higa says. “It was completely destroyed.”.

The captain then pulled out another photo. Higa recognized it instantly as his grandfather’s village, Shimabuku, which, up until five years ago, had been his home. “My hair stood up! For awhile I couldn’t even open my mouth; I was so choked up.”

Higa looked at the photo through a special three-dimensional glass capable of picking up minute details. “I instantly recognized my Grandpa’s home and from there, finger-traced all of my relatives’ houses.” To his relief, their homes were intact.

The captain then pulled out a shot of a typical country hillside in Okinawa. Higa glanced at it and then looked back at the captain with a “so what?” look. “Godammit, look carefully,” shouted the captain. “We think the whole island is fortified!” The captain had mistaken traditional Okinawan burial tombs for fortifications. “I suddenly realized the wrong impression the captain and other intelligence officers had.” Higa proceeded to give the officers a crash course in Okinawan culture.

He explained that Okinawans view their burial tomb as their permanent home. Thus, they try to build them on a hillside with a good view, overlooking the ocean. He also explained that the crater-like holes intelligence officers had observed in the comers of fields were composting pits used by farmers, not machine gun nests.

“From that time on, he (the captain) said, ‘Sgt. Higa, you’re going to assist us right through here.’” Higa was sworn to silence. When he returned to division headquarters later, his brother asked him what he had done during the day. “Don’t ask me, because I’ve been told not to say anything,” Takejiro replied.

Unbeknownst to him; Warren had informally volunteered his brother’s first-hand knowledge of Okinawa to the division brass in the event of an Okinawa invasion.

All the signs–the aerial photos, the questions–pointed to an Okinawan invasion. Higa says he knew of the plans at least five months before the actual strike. The only thing he didn’t know was the exact landing date.

Higa proved a big help to Corps headquarters because the area in which they landed was about a mile from where he had grown up.

“It was a horrible feeling,” he says. “Ever since the first day I saw the picture, every night I used to dream about my relatives. Every night … never miss,” Higa said, his voice breaking. “I dreamed about my uncle, my cousins, and even schoolmates.”

But as an American soldier, he had a duty to perform. The last thing he wanted to do was harm his former countrymen, but he didn’t know how he could do that without violating the military code of conduct.

“Deep inside I was torn,” he says. “That feeling is hard to describe. Unless you yourself experience it, you don’t appreciate it.”

By late December, Leyte had been secured. In March 1945 the soldiers in the 96th Division boarded a troop ship. On their second day at sea, they were told their destination: Okinawa.

Higa was often called to the radio shack to translate radio transmissions they had picked up from Okinawa. Most of the time they were music programs with some Okinawan language sprinkled in the broadcast.

The Okinawa offensive, code-named “Operation Iceberg,” began April 1. Early that morning the soldiers lined up on the deck.

“When the outline of Okinawa came up, I instantly recognized the hills. I couldn’t help but choke up,” Higa says almost 50 years later, fighting back tears, his voice breaking.

Only five years had passed since he left Okinawa, and his heart was being tugged in two opposite directions. “I’m an American G.I. I have a duty to perform, and yet I have a cultural obligation to Okinawa. I was really torn between loyalty and patriotism versus personal feeling … . I can tell you I had tears in my eyes.”

It was different for his brother Warren, he says. True, he was Uchinanchu and Okinawa was the land of his ancestors. But he had not established an emotional attachment to the island in his three years there. “In my case, I grew up there. Although I’ve been back in Hawaii over 50 years, even to this day, the little country roads and small ditches and taro patches that we played in seem more like a real homeland to me than Honolulu.”

Higa recites an old Japanese saying: “Mitsugo no tamashi hyaku made… The spirit of a 3-year-old child will last a hundred years.” “What you learn in your small kid time, you’ll never forget.”

Because of his first-hand knowledge of the area and the Okinawan dialect, Higa was assigned to the division’s advanced unit. They landed at the Chatan beachhead on the western side of the island.

Higa remembers his first image on land. “There were farm houses all on fire, farm animals all over the place, all dead, some of them burning.”

The soldiers began moving towards higher ground. While walking through a narrow road, Higa saw something move in a small roadside dugout. “My heart stopped beating.” Higa jumped back and took cover. Slowly he began walking toward the dugout. With his carbine trained, he ordered loudly, “Come out, whoever you are! Come out!”

Higa was so scared he can’t remember whether he spoke English, Japanese or Okinawan. “I meant to speak Uchinaguchi (Okinawan dialect), but I have a feeling it was a mixture of everything,” he laughs.

After returning to Hawaii in 1939, he had made a concerted effort to not speak Okinawan and to learn English. In the excitement of the moment, he says he wouldn’t be surprised if what he uttered was a mish-mash of Japanese, Uchinaguchi, English and pidgin.

There was no response to his order, so Higa began squeezing his trigger. Suddenly he saw a thin human leg appear. “'Njiti (come out) mensooree (please)!” he ordered in Uchinaguchi.

さらに読む

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hVaBKj7UPHw)

Day 2 of my trip to Gifu!

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

oh my god.

Omae wa mou niowanai = you are already odor-free

11K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RN42_kmbxuY)

I went on an adventure! It was pretty nice. My legs were KILLING ME.

1 note

·

View note