Text

Queens DA Katz Outlines Priorities: Public Safety, Conviction Integrity, and a Questionable Crackdown on Scooters http://dlvr.it/T57Hwg

0 notes

Text

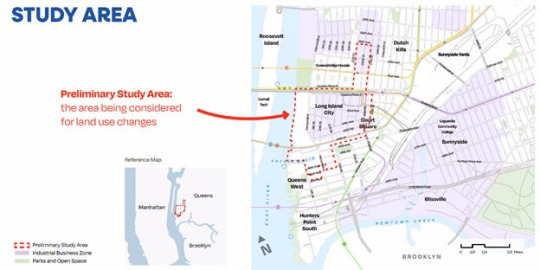

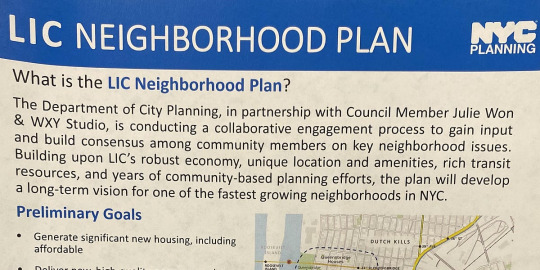

OneLIC Round 2: Residential development in the LIC IBZ http://dlvr.it/T25NJD

0 notes

Text

Impressionism, Inc.: An Examination of the Impressionists’ Société Anonyme http://dlvr.it/T017Dh

0 notes

Text

HPD's Vision for Hunter's Point South Parcel E http://dlvr.it/Szv3BY

0 notes

Text

The Future of Hunters Point South Ferry Landing http://dlvr.it/SyTHLH

0 notes

Text

Exploring the Proposed Long Island City Business Improvement District Expansion: A Community Meeting Recap http://dlvr.it/Swhwhp

0 notes

Text

Four things of note in tonight's CB2 meeting (September 2023) http://dlvr.it/SvngkW

0 notes

Text

How the LIC Courthouse intertwines with the creation of New York City http://dlvr.it/SjrK2s

0 notes

Text

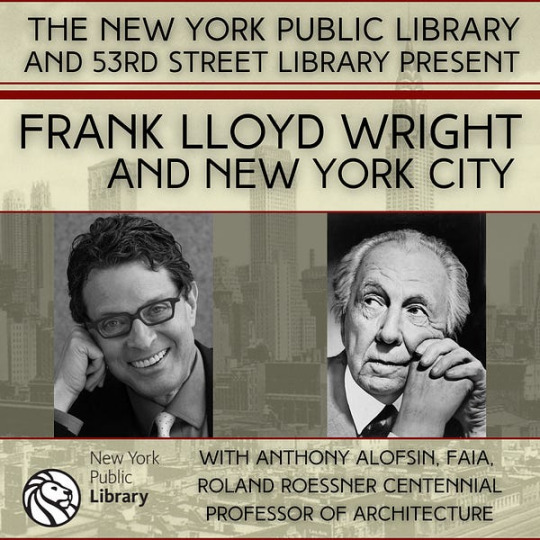

"The Crucible of New York": Frank Lloyd Wright's journey to becoming an iconic architect http://dlvr.it/Sjnbvq

0 notes

Text

Lochner and the Freedom of Contract

One of the theoretical underpinnings of laissez-faire capitalism is the freedom of contract, the idea that individuals and groups should be free to enter into any mutually agreed upon contract without interference from the government. Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, who laid the groundwork for free market economic theory, wrote in his 1776 classic The Wealth of Nations about what he considered to be the “sacred and inviolable” freedom of contract. “The patrimony of a poor man lies in the strength and dexterity of his hands; and to hinder him from employing this strength and dexterity in what manner he thinks proper, without injury to his neighbour, is a plain violation of this most sacred property. It is a manifest encroachment upon the just liberty, both of the workman, and of those who might be disposed to employ him” (Smith).

Early twentieth century American jurisprudence took a similar approach as Smith, enshrining the freedom of contract between employees and employers into law with Lochner v. New York in 1905 and striking down any major attempts to govern “this most sacred property.” America by the turn of the twentieth century had witnessed the rise of industrial capitalism, which led to a transformed labor relationship and new attempts at worker exploitation. It also led to a rise in unionization efforts and collective worker actions.

It was in this political climate that New York State passed a labor law limiting the working hours for employees of bakeries to a maximum of 60 hours per week or 10 hours per day. Employer Joseph Lochner argued that the freedom of contract protected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution rendered the state law illegal. The United States Supreme Court agreed, hearkening back to Smith’s defense of the freedom of contract, employed the same concept of “liberty.” The Court had already decided a few years earlier in Allgeyer v. Louisiana that “the general right to make a contract in relation to his business is part of the liberty of the individual protected by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitution.” In Lochner v. New York, the Court decided that “there is no reasonable ground for interfering with the liberty of person or the right of free contract by determining the hours of labor in the occupation of a baker.”

Reasonable grounds to use the state’s “police powers” to limit the freedom of contract would have included laws that “relate to the safety, health, morals and general welfare of the public.” However, because “the trade of a baker has never been regarded as an unhealthy one,” the Court found that “the act is not, within any fair meaning of the term, a health law, but is an illegal interference with the rights of individuals, both employers and employees, to make contracts regarding labor upon such terms as they may think best.” The question before the Court in Lochner v. New York was, in its own words, “which of two powers or rights shall prevail,—the power of the state to legislate or the right of the individual to liberty of person and freedom of contract.” The Court sided with the freedom of contract and struck down the New York State law limiting bakery employee working hours.

Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. dissented, striking at the heart of the freedom of contract and Smith’s economic theory. “A constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory, whether of paternalism and the organic relation of the citizen to the State or of laissez faire,” he wrote. Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan also dissented, arguing that “this statute was enacted in order to protect the physical wellbeing” of bakery employees. He also argued that the Court’s decision in Lochner v. New York would be “enlarging the scope of the [Fourteenth] Amendment far beyond its original purpose” (Lochner v. New York).

Indeed, this enlargement of scope would usher in a decades-long period known as the Lochner era, a period in which the Court broadly interpreted the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to strike over 200 federal and state labor laws. One analysis found that, “during the forty years comprising the Lochnerera, the Court used substantive due process to strike down government action an average of about five times a year” (Phillips).The Supreme Court was “effectively arguing that if a worker took a job, that worker agreed to whatever the employer offered and the government should not intervene in that sacrosanct arrangement,” historian Erik Loomis wrote in A History of America in Ten Strikes(Loomis p. 83).

Organized labor leaders criticized and fought against the Court’s overreach in the Lochner era. “In the depths of the Great Depression, workers transformed their lives through a combination of their organizing and electing politicians to office who would change the attitude of the state toward unions,” Loomis wrote (Loomis pp. 113-119). These decades saw a series of worker strikes and strike waves, including the 1912 Lawrence textile strike, the Seattle General Strike of 1919, and the 1936-1937 Flint sit-down strike – the last occurring during the severe industrial slump of the Great Depression.

It was a series of strikes during the Great Depression in 1934 (including the Auto-Lite strike, West Coast waterfront strike, Minneapolis general strike, and the textile workers strike) that compelled President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s federal government to pass the National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act) the following year. The NLRA undermined the freedom to contract of the Lochner era by promoting union organizing and collective bargaining, as well as by creating the National Labor Relations Board to manage relations between employees and employers.

It wasn’t until West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish in 1937 that the Supreme Court allowed for more regulation of the labor contract by upholding a minimum wage law for women, finally bringing the Lochner era to a close. In West Coast Hotel, the Court struck at the core of the idea of the freedom of contract, writing, “The violation alleged by those attacking minimum wage regulation for women is deprivation of freedom of contract. What is this freedom? The Constitution does not speak of freedom of contract.” The Court wrote that the Constitution instead “requires the protection of law against the evils which menace the health, safety, morals and welfare of the people” (West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish). For this reason, it is sometimes necessary to curtail liberty and to enact restrictions on the freedom of contract, including restrictions related to the minimum wage. The Court’s decision echoed Harlan’s Lochner dissent decades earlier, in which he argued, “I take it to be firmly established that what is called the liberty of contract may, within certain limits, be subjected to regulations designed and calculated to promote the general welfare or to guard the public health, the public morals or the public safety” (Lochner v. New York).

The Court’s decision in West Coast Hoteltook the point of public health even further, holding that “this established principle is peculiarly applicable in relation to the employment of women, in whose protection the State has a special interest.” The Court asked rhetorically, “What can be closer to the public interest than the health of women and their protection from unscrupulous and overreaching employers?” It also cited the 1908 case Muller v. Oregon, which limited the number of hours women could work and “emphasized the consideration that ‘woman's physical structure and the performance of maternal functions place her at a disadvantage in the struggle for subsistence,’ and that her physical wellbeing ‘becomes an object of public interest and care in order to preserve the strength and vigor of the race.’” Loomis wrote that, in cases such as Muller, “Progressives saw women as not only exploited workers but also mothers responsible for raising the next generation of Americans. They argued that the state had a unique interest in excepting women from the freedom of contract ideology of Lochner and the Gilded Age Courts.” With cases like Muller, “creating any exception to Lochner opened up the court to more exceptions” (Loomis p. 84). With West Coast Hotel, the minimum wage statute for women was upheld, and the notion of a freedom of contract was weakened for all workers and employers.

A century later, the Lochner era is today considered by many legal theorists to be “one of the Supreme Court’s darkest eras” – with the decision “in a Malebolge of rejected rulings,” along with the infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson(Beutler). But the Lochner decision and its underlying idea of freedom of contract continue to draw support from some modern conservative and libertarian legal thinkers, who “condemn Lochner for improper ‘judicial activism’” and “increasingly argue that in completely abandoning Lochner, the Court has left important economic rights vulnerable to government overreaching,” according to legal scholar David Bernstein (Bernstein). These libertarians are trying to rehabilitate the Lochner decision and “argue that the Constitution exists to secure inalienable property and contract rights for individuals.” West Coast Hotel may have effectively overturned Lochner, but the Lochner idea of freedom of contract is still alive.

References

Bernstein, D. E. (2005). Lochner v. New York: A Centennial Retrospective. Washington University Law Review, 83(5). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/233178567.pdf.

Beutler, B. (n.d.). The Rehabilitationists. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/122645/rehabilitationists-libertarian-movement-undo-new-deal.

Klare, K. E. (1978). Judicial deradicalization of the Wagner Act and the origins of modern legal consciousness, 1937-1941. School of Law Faculty Publications. https://legalform.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/klare-judicial-deradicalization-of-the-wagner-act-and-the-origins-of-mo.pdf.

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905). Justia Law. (n.d.). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/198/45/.

Loomis, E. (2020). A History of America in Ten Strikes. The New Press.

Phillips, M. J. (1997). How Many Times Was Lochner-Era Substantive Due Process Effective? Mercer Law Review, 48(3). https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1597&context=jour_mlr.

Smith, A. (2009). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3300/3300-h/3300-h.htm.

West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish. Justia Law. (n.d.). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/300/379/.

0 notes

Text

Free Labor vs. Wage Slavery

American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois famously conceived of slavery as a relationship based inherently in labor terms – the slaveholder was an owner of human chattel whose control over and exploitation of the worker/slave was absolute. “Slavery is fundamentally a labor system,” historian Erik Loomis wrote in his book A History of America in Ten Strikes, citing Du Bois, who “called slave self-emancipation a ‘general strike’” that occurred at the onset of the Civil War with slaves “walking away from the plantations [and] withholding their labor from masters who increasingly could not control them” (Loomis, p. 30). Even after the abolition of slavery with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, vestiges of the institution remained in the labor relationship between former slaveholders and newly emancipated former slaves, which – in many cases – resembled slavery in all but name. While “freedpeople remained adamant in the desire to work without the supervision of masters and overseers, to determine their own hours and pace of labor, and to receive wages commensurate with their effort,” historian Eric Foner wrote in his book Forever Free, “most white southerners insisted that blacks must remain a dependent plantation labor force in a situation not very different from slavery [and] sought to reestablish their authority over the former slaves through labor contracts” (Foner & Brown, pp. 91-93).

The former slaveholders’ assertion flew in the face of the freedpeople’s belief in free labor, an ideology imported from the North that “rested on the idea that the opportunity to improve one’s condition in life was a far more effective spur to efficient labor than the coercion of slavery” (Foner & Brown, p. 98). Critics of this free labor system ranged from white slaveholders who had wished to protect their economic interests in owning slaves (“the liberty of the northern wage earner … amounted to little more than the freedom to sell his labor for a fraction of its value, or to starve,” said Vice President John C. Calhoun, one of the most ardent defenders of slavery) (Zietlow, pp. 54-55) to white labor leaders who wished to improve labor conditions (“the chattel slave of the past-the wage slave of today; what is the difference? … formerly the master selected the slave; today the slave selects his master,” said labor activist Albert Parsons in a speech to the court during the infamous Haymarket trial) (The Accused, the accusers).

As post-Civil War America gave way to Gilded Age capitalism, these criticisms of free labor ideology gained even more of a foothold. “The new industrial capitalism made a few millionaires the new masters and white workers compared themselves to slaves because their free labor ideology had proven false,” Loomis wrote (Loomis, p. 50). Slavery may have been a labor system, but free labor was a slave system, they argued – coining the term “wage slavery” to describe the plight of the wage laborer. Eventually, even freedpeople who had once been buoyed by the idea of free labor as progress soured on the thought and began to make direct connections between working conditions under wage labor and slavery. Abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass said in 1883, “Experience demonstrates that there may be a wages of slavery only a little less galling and crushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and that this slavery of wages must go down with the other” (Address of Hon. Fred. Douglass).

Among the central grievances workers had with the system of wage labor were the treacherous and taxing conditions under which they worked, the low pay they received, and the stark difference between the wages they received and the riches amassed by their capitalist masters. “These capitalists made their fortunes on the backs of workers suffering through increasingly brutish and nasty lives,” Loomis wrote. “Workers died by the hundreds in mine accidents, by the dozens in factory fires, and one at a time in meatpacking plants and sawmills” (Loomis, p. 51). At the same time, the capitalist class (such as railroad executives) “agreed to cut their employees' wages even as they announced substantial dividends for their stockholders,” with one railroad baron saying, “The great principle upon which we joined to act was to earn more and spend less” (1877: The Grand Army of Starvation Script). The conditions of the Gilded Age persisted well into the early twentieth century and were perhaps best exemplified in the tragedy of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, in which the low-paid wage laborers (“they got whatever the contractor wanted to pay … Triangle and the inside contractor got the difference”) suffered terrible working conditions and, eventually, a tremendous loss of life (Stein, p. 161).

When wage laborers attempted to band together to collectively oppose these working conditions, a number of significant legal decisions threw the weight of the American government behind the capitalist class and by ruling consistently against unions, reinforcing the criticism that wage slavery had a stranglehold on the employment relationship. As early as 1806, Commonwealth v. Pullis held that any collective attempt to withhold labor in order to negotiate higher wages constituted criminal conspiracy (“a combination of workmen to raise their wages may be considered in a two fold point of view; one is to benefit themselves ...the other is to injure those who do not join their society”) (Commonwealth v Pullis). It wasn’t until almost four decades later, in the 1842 case Commonwealth v. Hunt, that a court ruled that criminal conspiracy charges didn’t apply to unions that used proper means to achieve their goals (“associations may be entered into, the object of which is to adopt measures that may have a tendency to impoverish another, that is, to diminish his gains and profits, and yet so far from being criminal or unlawful, the object may be highly meritorious and public spirited”) (Commonwealth v. Hunt). But even a half century later, the 1896 case Vegelahn v. Guntner showed the government’s antipathy toward union activities by ruling the state could issue injunctions against basic union activities such as picketing (“a combination to do injurious acts expressly directed to another, by way of intimidation or constraint, either of himself or of persons employed or seeking to be employed by him, is outside of allowable competition, and is unlawful”) (Vegelahn v. Guntners).

In the early twentieth century, courts further weakened union power by enjoining union organizing on the ground that it interfered the right of individual workers to enter into employment contracts with employers. In the 1905 case Lochner v. New York, the Supreme Court explained, “the freedom of master and employee to contract with each other in relation to their employment, and in defining the same, cannot be prohibited or interfered with without violating the Federal Constitution” (Lochner v. New York). Loomis commented that the Court effectively found “that if a worker took a job, that worker agreed to whatever the employer offered and the government should not intervene in the sacrosanct arrangement. Such a worldview completely ignored the vast disparities of power between an employer and a worker desperate to eat” (Loomis, p. 83).

Piling on to these judicial rulings and evoking the era of state-sanctioned (or even state-sponsored) violence visited upon slaves, the government also supported employers over wage laborers by agreeing to allow state-sanctioned violence against strikers. “Violence or the threat of violence associated with employee collective action was of course an unlawful means and could serve as a basis of injunction under the civil conspiracy doctrine. Often, this violence was instigated by ‘security’ personal retained by the employer to break the strike, for example—the murders of coal miners’ wives and children in the Ludlow massacre that occurred in the 1913-14 miners’ strike against John D. Rockefeller’s Colorado Fuel and Iron Company” (Dau-Schmidt et al., Labor Law in the Contemporary Workplace p. 32). Other times, the violence was carried out directly by the state through executive interventions, including in the Haymarket massacre (by the Chicago Police Department), the anthracite coal strike (“the mine owners responded to strikes with state-sponsored violence” by the Pennsylvania national guard) (Loomis, p. 79), and the Pullman strike (President Grover Cleveland “called in the military to quash the strike”). “The Pullman strike was largely nonviolent until the military intervened,” Loomis wrote. “Pullman showed yet again that the government would assist corporations in destroying working-class movements” (Loomis, p. 74). Even the young women who participated in the New York shirtwaist strike of 1909, which preceded the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire by two years, felt the wrath of state violence. Clara Lemlich, a leader of the strike, “suffered six broken ribs when police beat her” (Loomis, p. 85). After the strike was broken, only some modest concessions were given, and the fire claimed the lives of scores of wage laborers, one woman said that “it was the same policemen who had clubbed them back into submission who kept the thousands in Washington Square from trampling upon their dead bodies, sent for ambulances to carry them away and lifted them one by one into the receiving coffins” (Stein, p. 168).

As the Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era and the radicalism of some of the early labor leaders gave way to a more moderate form of trade unionism in the twentieth century, so too did the idea of “wage slavery” (and the term itself) fall out of favor, replaced by the more palatable “wage work.” “This linguistic shift is of particular scholarly importance because it occurred during a time when producerist labor politics, with its emphasis on a radical reorganization of work and private property, lost significant ground to a more consumerist/economistic version of labor politics,” wrote sociologists Helga Kristin Hallgrimsdottir and Cecilia Benoit in a 2007 paper, showing “how the once dominant imagery of ‘wage slavery’ lost its connection to producerist labor ideology and eventually was replaced by the more pragmatic symbolism of ‘wage work’” (Hallgrimsdottir & Benoit). Still, the idea and the term of wage slavery persists to this day in some debates, including in conversations around the minimum wage. “To be working and homeless, that is taking advantage of people,” said Pam Garrison of the West Virginia Poor People's Campaign (which advocates for poor and low-income people) earlier this month. “You’re getting us for slave wages … And when you work and still need help to put food on the table, that’s immoral” (West Virginia workers keep pressure on Manchin for $15 wage).

References

American Social History Project. 1877: The Grand Army of Starvation Script (for chapters on "The Centennial Exposition" and "The Railroad") · SHEC: Resources for Teachers. 1877: The Grand Army of Starvation Script. https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1920.

Chicago Historical Society Haymarket Affair Digital Collection. HADC - The Accused, the accusers, speech of Albert R. Parsons, pp. 90 - 188. The Accused, the accusers, speech of Albert R. Parsons, pp. 90 - 188. http://www.chicagohistoryresources.org/hadc/books/b01/B01S008.htm.

Colored Conventions Project Digital Records. Address of Hon. Fred. Douglass, delivered before the National Convention of Colored Men, at Louisville, Ky., September 24, 1883. Address of Hon. Fred. Douglass. https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/554.

COMMONWEALTH vs. JOHN HUNT & others. HUNT, COMMONWEALTH vs., 4 Met. 111, 45 Mass. 111. http://masscases.com/cases/sjc/45/45mass111.html.

Dau-Schmidt, K. G., Malin, M. H., Corrada, R. L., Ruiz, C. C. D., & Fisk, C. L. (2019). Labor law in the contemporary workplace. West Academic Publishing.

Foner, E., & Brown, J. (2006). Forever free: the story of emancipation and Reconstruction. Vintage Books.

FREDERICK O. VEGELAHN v. GEORGE M. GUNTNER & others. VEGELAHN vs. GUNTNER, 167 Mass. 92. http://masscases.com/cases/sjc/167/167mass92.html.

Hallgrimsdottir, H. K., & Benoit, C. (2007). From Wage Slaves to Wage Workers: Cultural Opportunity Structures and the Evolution of the Wage Demands of the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor, 1880-1900. Social Forces, 85(3), 1393–1411. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0037

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905). Justia Law. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/198/45/.

Loomis, E. (2020). A history of America in ten strikes. The New Press.

Stein, L. (2011). The Triangle fire. ILR Press/Cornell University Press.

University of Massachusetts. Commonwealth v Pullis. https://blogs.umass.edu/ulaprog/files/2008/06/commonwealth-v-pullis.pdf.

West Virginia workers keep pressure on Manchin for $15 wage. People's World. (2021, February 18). https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/west-virginia-workers-keep-pressure-on-manchin-for-15-wage/.

Zietlow, R. E. (2019). The forgotten emancipator: James Mitchell Ashley and the ideological origins of Reconstruction. Cambridge University Press.

0 notes

Text

The History of the Trylon Theater

The symbols of the 1939 New York World's Fair, held at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens, were the gleaming white Trylon (a three-sided 610-foot pillar) and Perisphere (a sphere with a 180-foot diameter) that dominated the fairgrounds from miles away (Fiederer, 2016). The abstract modernism of the structures, which were featured extensively on advertising and memorabilia, was praised by architecture critics, for having “earned an enduring legacy as one of the world’s greatest symbols of hope for the future when there seemed to be no hope at all – a vision of the World of Tomorrow that has yet to be forgotten.”

One legacy of the Trylon was the 600-seat Trylon Theater in Rego Park, Queens, which also opened in 1939 and was named after the famous World’s Fair pillar (Perlman, 2016). The theater was designed by New York architect Joseph Unger in the popular geometric Art Deco style of the time. The theater boasted “a streamlined stone façade with a glass brick projection tower illuminating Queens Boulevard.” Other attractive design elements included “the Trylon monument’s depiction in a mosaic tile ticket booth, the exterior terrazzo floor and mosaic chevrons, and an interior backlit fountain.” Nearby retail establishments were also named after the Trylon and “piggy-backed on the theater’s success” – Trylon Soda & Ice Cream, Trylon Realty, Trylon Tailors and Trylon Liquors. The Trylon Theater remained in operation for 60 years, until it closed in 1999 as one of the last remaining single-screen theaters in the city.

After the Trylon Theater’s lease expired at the turn of the century, the building was purchased by a group of local Bukharian Jews to use as a cultural center called the Educational Center for Russian Jewry (Vandam, 2005). Local preservationists, eager to preserve the history of the Trylon Theater, were dismayed that elements of the theater’s architecture were being lost in the construction for the cultural center. “They've already torn out the whole lower facade,” said John Jurayj, co-chairman of the Modern Architecture Working Group. “It was a completely intact Art Moderne entryway. I'm trying to think of what other things there are in this style, and I kind of draw a blank.”

But the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission disagreed when local preservationists tried to have the theater designated as a New York City landmark: “According to Robert Tierney, chairman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the theater has been considered for landmark status but never been the subject of a vote. For various reasons, he said, it does not meet the commission's landmark criteria.” Indeed, in a wide-ranging article on New York City’s Landmarks Law and the Rescission Process, Joachim Beno Steinberg wrote that preservationists may have failed in their bid to landmark the Trylon Theater because the theater is not a unique example of its architectural style (Steinberg, 2011). “The scarcity of buildings exhibiting a particular style of architecture is a valuable consideration, because it allows the city to find a balance between the public benefits of having historical buildings against the economic needs of the city,” Steinberg wrote. “For example, if the Trylon Theater had been the last Art Deco movie house left in the city, then perhaps it would have been more crucial to save it.”

District Attorney of Queens County Melinda Katz, then the City Council Member of the district that housed the Trylon Theater, said at the time, “It's a much-needed center for the Bukharan community, and I look forward to working with them … I'm just not sure at this time if landmarking just the front of the building would be the best for the community” (Vandam, 2005).

References

Fiederer, L. (2016, December 11). AD Classics: Trylon and Perisphere / Harrison and Fouilhoux. ArchDaily. Retrieved November 16, 2020, from https://www.archdaily.com/800746/ad-classics-trylon-and-perisphere-harrison-and-fouilhoux

Perlman, M. (2016, January 19). The Trylon: The Theater of Tomorrow. Forest Hills Times. Retrieved November 16, 2020, from http://www.foresthillstimes.com/view/full_story/27050355/article-The-Trylon--The-Theater-of-Tomorrow

Steinberg, J. B. (2011). New York City's Landmarks Law and the Rescission Process. NYU Anneal Survey of American Law, 66(95), 951-1000. Retrieved November 16, 2020, from https://annualsurveyofamericanlaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/66-4_steinberg.pdf

Vandam, J. (2005, September 18). For an Art Moderne Theater, a Struggle Over Act II. The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/18/nyregion/thecity/for-an-art-moderne-theater-a-struggle-over-act-ii.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Race for City Council District 29

Although, until recently, most of New York City’s political focus was on the 2020 elections, the 2021 elections will also be significant for the city. With Mayor Bill de Blasio term-limited, a number of challengers have already declared their candidacy – including Comptroller Scott Stringer, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Shaun Donovan, and former chair of the Civilian Complaint Review Board Maya Wiley (Coltin, 2020). But with substantially less fanfare than the citywide mayoral race, there will also be elections for all 51 seats on the New York City Council. The 2021 City Council primaries will also make history as the first in the city to be decided by ranked-choice voting (Geringer-Sameth, 2020).

In District 29 – which encompasses the neighborhoods of Forest Hills, Rego Park, Kew Gardens, and Richmond Hill – City Council member Karen Koslowitz is term-limited, and the race to succeed her is wide open. Karen Koslowitz was first elected to her seat for two terms in 1991, and then re-elected to her seat for two more terms in 2009, with a stint as Queens Deputy Borough President in the interim (District 29 - Karen Koslowitz). Now that she’s ineligible to run again, a new era of electoral politics in central Queens in set to begin, and ten candidates have filed to run for City Council District 29 with the New York City Campaign Finance Board (Candidate List - 2021 Citywide Elections).

Among the challengers are several of my friends and neighbors – including Lynn Schulman, David Aronov, Edwin Wong, and Aleda Gagarin. Schulman – who has been active in the community for decades as part of the local community board, police precinct community council, chamber of commerce, and community education council (Meet Lynn) – would make history as the first openly lesbian elected official in Queens (Cardoso, 2020). Schulman ran for but lost the seat in 2001 and 2009, but has quickly emerged as the frontrunner this time around – having raised seven times as much money as all other candidates combined (Campaign Finance Summary). Aronov, who worked for Koslowitz as a community liaison and currently census organizing efforts for Queens, will be just 25 years old during next year’s election (Kadinsky, David Aronov Council Run: Would Be First Bukharian Elected). As a co-founder of the Bukharian Jewish Union, Aronov is looking to become the area’s first Bukharian representative (Kadinsky, 2020). Wong – president of the Forest Hills Asian Association, community board member, and banker – is also looking to tap into changing demographics and hoping to be the area’s first Asian representative (Krevoy, FHAA president runs for City Council). Gagarin – a nonprofit fundraiser and former campaign manager for her husband Mel’s Congressional campaign – is perhaps the most outspokenly progressive challenger in the race (About - Aleda Gagarin for NYC Council District 29). (Mel came in second in his race against Representative Grace Meng, with 20% of the vote.) Other challengers in the City Council race include Evan Boccardi, Eliseo Labayen, Marcelle Lashley-Kabore, Sharon Levy, Douglas Shapiro, and Donghui Zang.

Why are all of these people running for this position on the City Council to represent District 29? One answer to that question can be found in the writings of urbanist Jane Jacobs, who wrote about the importance of a district in a city. In her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs divided the city into three geographic and political divisions. “I can see evidence that only three kinds of neighborhoods are useful,” she wrote, “1) the city as a whole; 2) street neighborhoods; 3) districts of large subcity size, composed of 100,000 people or more in the case of the largest cities” (Jacobs, 1961). (Indeed, the combined population of Forest Hills and Rego Park – the two main neighborhoods in City Council 29 – is about 130,000.) For Jacobs, “the chief function of a successful district is to mediate between the indispensable, but politically powerless, street neighborhoods and the inherently powerful city as a whole.” This mediation happens in both directions. The district helps direct much-needed city resources to the street-level neighborhood, as well as inform the city of street-level needs and trends. But even more than mediation, a district has to have a rivalrous relationship with the city. Jacobs puts it bluntly when discussing the ideal size of a district: “A district has to be big and powerful enough to fight city hall.” The reason for this potential to fight is because “nothing is more helpless than a city street alone, when its problems exceed its powers.” In these situations, “sometimes the city is not the potential helper, but the antagonist of a street, and again, unless the street contains extraordinarily influential citizens, it is usually helpless alone.” Jacobs wrote that whenever citizens at the street-level neighborhood wanted to fight the city, they “needed power to back up [their] pipsqueak protest. The power came from our district.”

So much of what Jacobs wrote generally about districts in a city can be applied to City Council District 29 specifically. Much of what our next City Council member will be expected to do is to mediate between the street-level neighborhoods of Forest Hills and Rego Park and the City of New York as a whole. It is this unity of street-level neighborhoods that makes a district powerful enough to stand up to the city.

References

About - Aleda Gagarin for NYC Council District 29. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.aledaforcouncil.com/about

Cardoso, J. (2020, June 19). 2021 City Council Candidate Lynn Schulman endorsed by national LGBTQ organization. Queens County Politics. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.queenscountypolitics.com/2020/06/19/2021-city-council-candidate-lynn-schulman-endorsed-by-national-lgbtq-organization/

Coltin, J. (2020, September 24). How Johnson’s exit boosts Stringer in 2021. City & State New York. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.cityandstateny.com/articles/politics/campaigns-elections/how-johnsons-exit-boosts-stringer-2021.html

District 29 - Karen Koslowitz. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://council.nyc.gov/district-29/

Geringer-Sameth, E. (2020, August 28). Board of Elections Presents Plan for 2021 Implementation of Ranked-Choice Voting. Gotham Gazette. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.gothamgazette.com/city/9716-how-ranked-choice-voting-will-be-implemented-in-2021

Jacobs, J. (1961). The uses of city neighborhoods. In The death and life of great American cities (pp. 112-140). New York, NY: Random House.

Kadinsky, S. (2020, July 29). David Aronov Council Run: Would Be First Bukharian Elected. Queens Jewish Link. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.queensjewishlink.com/index.php/local/20-community-corner/by-sergey-kadinsky/2943-david-aronov-council-run-would-be-first-bukharian-elected

Krevoy, S. (2020, August 12). FHAA president runs for City Council. Forest Hills Times. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from http://foresthillstimes.com/view/full_story/27767597/article-FHAA-president-runs-for-City-Council?instance=lead_story_left_column

Krevoy, S. (2020, August 5). Community organizer eyes City Council seat. Forest Hills Times. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from http://foresthillstimes.com/view/full_story/27766401/article-Community-organizer-eyes-City-Council-seat?instance=home_news_bullets

Meet Lynn. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.schulman2021.com/about-lynn

New York City Campaign Finance Board. (n.d.). Campaign Finance Summary. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.nyccfb.info/VSApps/WebForm_Finance_Summary.aspx?as_election_cycle=2021

New York City Campaign Finance Board. (n.d.). Candidate List - 2021 Citywide Elections. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.nyccfb.info/follow-the-money/candidates/

0 notes