Text

Why poverty is about more than money: socioeconomic status and its deep impacts on the brain

Being in poverty obviously has its negatives in terms of not being able to live lavishly; maybe one lives in a food desert, or they have to share one bedroom with two children. In this breakdown, though, I intend to discuss the impacts of being poor past the outside appearances and finances: both being and growing up in poverty seem to fundamentally affect the brain for the worse.

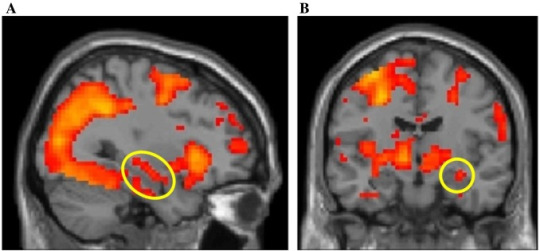

Duval et al. (2017) had healthy 9-year-olds of varying socioeconomic status perform a visuospatial memory task during an fMRI scan, and followed these children into young adulthood where they completed a similar memory task under an fMRI. Childhood income level and both recognition accuracy and hippocampal function were directly related; childhood poverty was directly associated with a deficit in hippocampal function.

Circled below is the activation cluster Duval et al. (2017) was focused on:

Tomarken et al. (2004) looked at frontal brain asymmetry as a possible predictor for depression and found that adolescents with a high risk of depression (mothers with a history of it) demonstrated this asymmetry based on EEG; a left frontal region hypoactivity. Further, socioeconomic status was also found to be a predictor of this asymmetrical function, with activity increasing with status:

Noticeably and understandably, most of these studies discuss children being raised in poverty; in the first year of life and onward, socioeconomic status seems to have an impact on many neurocognitive processes, most notably language and executive function (Hackman et al., 2009). Even independently of adult earnings, childhood poverty predicts a more aggressive amygdala and mPFC response to threatening vs. happy faces via fMRI (Javanbakht et al., 2015).

It’s important to note that coping with poverty can happen in a variety of different ways; some of these discrepancies could be accounted for by differing parental education levels, a lack of nutrition due to not being able to afford food, maybe even poor living conditions that could directly lead to cognitive deficit through things like mold inhalation (Harding et al., 2020).

Lipina et al. (2017) broadly discuss the ethical implications of this kind of research and what we can do to learn from it in terms of trying to tackle poverty and its effects. They break it down into 3 main concerns:

The causes of poverty and attitudes toward it: how neuroscience may contribute to people with individualistic attitudes toward those in poverty, and how to do neural/behavioral differences in those who come from poverty could contribute to this

Poverty's impacts on brain development: looking at possible societal issues arising that, when solved could help fix this.

What can we change?: what parts of poverty have the potential to be worked with; are these developmental stunts in children "reversible"?

However, the main purpose of this is not to say that there’s one thing we can do to solve poverty. Rather, the purpose of this post is to bring attention to the individualists saying “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” or those accusing people of low socioeconomic status of just not working hard enough, and they may not grasp the head start they have over someone who grew up in poverty. A head start in money is one thing, sure, but the discussed metrics differentiating brain function in those in poverty and those not are hard to ignore.

References:

Duval, E. R., Garfinkel, S. N., Swain, J. E., Evans, G. W., Blackburn, E. K., Angstadt, M., Sripada, C. S., & Liberzon, I. (2017). Childhood poverty is associated with altered hippocampal function and visuospatial memory in adulthood. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 23, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2016.11.006

Hackman, D. A., & Farah, M. J. (2009). Socioeconomic status and the developing brain. Trends in cognitive sciences, 13(2), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.003

Harding, C. F., Pytte, C. L., Page, K. G., Ryberg, K. J., Normand, E., Remigio, G. J., DeStefano, R. A., Morris, D. B., Voronina, J., Lopez, A., Stalbow, L. A., Williams, E. P., & Abreu, N. (2020). Mold inhalation causes innate immune activation, neural, cognitive and emotional dysfunction. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 87, 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.006

Javanbakht, A., King, A. P., Evans, G. W., Swain, J. E., Angstadt, M., Phan, K. L., & Liberzon, I. (2015). Childhood Poverty Predicts Adult Amygdala and Frontal Activity and Connectivity in Response to Emotional Faces. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9, 154. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00154

Lipina, S. J., & Evers, K. (2017). Neuroscience of Childhood Poverty: Evidence of Impacts and Mechanisms as Vehicles of Dialog With Ethics. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 61. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00061

Tomarken, A. J., Dichter, G. S., Garber, J., & Simien, C. (2004). Resting frontal brain activity: linkages to maternal depression and socio-economic status among adolescents. Biological psychology, 67(1-2), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.011

1 note

·

View note