Text

Repressed by male guardianship, women in Qatar flee in search of freedom and safety

Qatari women need a man's permission to travel and go to medical appointments, and are still unprotected by the country's laws

Article published in December 15th, 2022

Translated from Portuguese to English

Portal R7

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/reprimidas-por-tutela-masculina-mulheres-no-catar-fogem-em-busca-de-liberdade-e-seguranca-15122022/

Qatari women pose for a photo in Doha

The gender inequality in Qatar, highlighted by the FIFA World Cup in the country, exposes the differences between the lives of men and women. Women are prevented from making important decisions about their own lives due to a system of male guardianship.

On the fringes of society, they must show permission from their husband or father to travel abroad until the age of 25, get married, access reproductive health services, and even basic care.

According to the director of Human Rights Watch in Brazil, Maria Laura Canineu, “many women say this issue greatly affects their lives and mental health. There are many cases of women with depression and suicidal thoughts.”

The radicalisation they are exposed to is related to the interpretation of Sharia (Islamic law derived from religious guidance), the main source of the country's Constitution.

Manuel Furriela, a professor of International Relations at FMU (Faculdades Metropolitanas Unidas), explains the importance of emphasising that "not necessarily what is in religious precepts has the same intention. Laws are subject to interpretations, which can be varied."

Where is Noof al-Maadeed?

Noof al-Maadeed, 24, fled Qatar and claimed to have suffered attacks from her family

The Qatari young woman, Noof al-Maadeed, became well-known after deciding to flee the country to try and start a new life in London, England, and documenting her journey on social media. She claimed that had to leave Qatar because she suffered abuse and murder attempts from her family. Al-Maadeed caused concern when she disappeared from social media in October 2021 upon returning to Qatar. Speculations began to arise about the conditions of the young woman, with many people suggesting that she might have been murdered.

Human rights organisations started to pressure Qatar, and the hashtag #whereisNoof began to circulate until the young woman reappeared on Twitter in January of this year.

“I’m fine, I’m healthy and safe. This video is to reassure all those who showed their support," she posted.

She didn’t give explanations for her absence and said that created a new Twitter account after losing the password for the previous one, where she had over 16 thousand followers. Currently, Noof has returned to the original profile, but has stopped making constant posts.

"Qatar has greatly developed its capacity for online surveillance of people in recent years," says the director of Human Rights Watch.

"In the country, there is no law that protects women from domestic violence," she explains. "Many women who want to escape an abusive relationship risk being returned to their families and imprisoned. We have also seen cases of victims sent to psychiatric hospitals."

The specialist affirms that it is very difficult to question the country's rules because there is no freedom of expression for that. Therefore, the pressure from the international community becomes crucial.

Escape plan during family trip

Aisha al-Qahtani fled Qatar in search of freedom

Aisha al-Qahtani decided to leave Qatar to escape the oppressions experienced in the country. The young woman also fled to London in December 2019 during a trip with her family to Kuwait.

Qatar is the only country in the Gulf Cooperation Council that still requires women under 25 to have a man's permission to travel abroad.

"It was like I needed someone to pinch me because I couldn't believe I was really escaping,’" said Al-Qahtani in an interview to the program 60 Minutes Australia.

"I told myself that if I were a blonde, blue-eyed girl, my family would just say 'have a good trip,'" she added.

For Maria Laura Canineu, the FIFA World Cup “didn’t do much” for women's rights in Qatar. "The system of male guardianship will not end unless there is a global will to pressure the country in a way that it starts to rethink its practices."

Sexual Violence

The director of Human Rights Watch emphasises the risks of sexual violence are exacerbated during major events. The situation becomes even more serious in a country where victims are unprotected by the law.

She states that Qatar's legislation does not respect the guidelines of the United Nations International Community, and breaks the commitment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which prioritises the dignity of individuals.

"Women who report sexual violence in the country risk being prosecuted because Qatar's penal code criminalises sexual relations outside of marriage," she explains.

"If the aggressor claims that the relationship was consensual, a married woman risks being charged with the offence, which is one of the heaviest in terms of penalty, with almost seven years of imprisonment".

0 notes

Text

Ukrainian Joan of Arc: Businesswoman leaves jewellery store to fight as a sniper

Emerald Evgeniya returned to wear Army uniform after 12 years to fight against the Russians, and is the only woman among 100 men in the special forces troop

Article published in March 16th, 2022

Translated from Portuguese to English

R7 PORTAL - Journalistic scoop

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/joana-darc-ucraniana-empresaria-abandona-loja-de-joias-para-lutar-na-guerra-como-sniper-27062022/

Emerald Evgeniya holds weapon after returning to the Ukrainian Army

Before the Russian invasion in Ukraine, Emerald Evgeniya had a quiet life with her daughter

in Kiev, where she used to run her own jewellery store. The Ukrainian decided 12 years ago to leave the Army to become a “businesswoman”, as she likes to say.

“As soon as the war started, I quit my career and went back to the Army. Now, I work for the Special Forces intelligence and serve as a sniper. I’m the only woman among a hundred soldiers,” she says.

A sniper has a great responsibility on the battlefield and undergoes intense training to reach the rank. The weapon used by the soldier allows hitting targets very far away. Hitting an enemy with a lower risk of being counterattacked is one of the perks.

“I fight because it is my duty and I believe in Ukraine's great future. I feel like I have been preparing for this situation all my life. Also, I get support, people call me the Ukrainian Joan of Arc.”

Emerald is among thousands of soldiers trying to protect Ukraine as long as they face Russian Armed Forces. The Ukrainian population helps as much as they can, and even resorts to using mediaeval weapons to contain enemy tanks. Caltrops are made with sharp iron spikes and are scattered around Kiev.

Men and women with little or no experience volunteer to receive training and equipment to face the Russians. Currently, anyone who wants to serve must be between 18 and 60 years old and have an Ukrainian passport.

Emerald says the most difficult moment of the war was when she finally came across the Russian Army. “I started shooting again and realised I was face to face with one of their soldiers. This happened on the second day of combat, I was scared, but now I understand that this is my reality.”

The business woman’s life has changed radically in the last 21 days, in the same way for millions of Ukrainians. “I used to have a life of luxury, today I only live with my military uniform, mobile phone, two pairs of socks and a pair of shoes. I have also made donations to many people who lost their homes. I think after the war, if I survive, I can earn that money back with my work.”

Emerald during military training

Since the Russian invasion, more than 3 million people have left Ukraine, according to the UN-linked International Organization for Migration (IOM). Around 1.4 million are children, and among them is Jasmine, 10, Emerald’s daughter. When the war started, the little girl was sent to Poland.

“I’m in the Army because I want my daughter to live in a free country. I won’t leave until we win this war. I want peace and freedom for my family and for all Ukrainians,” explains Emerald.

Emerald and her daughter Jasmine

As the bombings advance and the soldiers try to prevent the capital, Kiev, representatives of the two countries are trying to reach an agreement. This Tuesday (15), Mykhailo Podoliak, negotiator and adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy, and Vladimir Medinsky, adviser to the Kremlin, resumed the fourth round of negotiations.

On the other hand, NATO members are spreading sanctions to increasingly isolate Russia. The sniper, however, believes that the way to contain the Russian advance would be the closure of Ukrainian airspace, which Zelenskiy has long requested. “We are strong in terrestrial space, but we are not safe in the sky.”

“I won’t leave until we win this war, and I believe Ukraine will be victorious,” added Emerald.

0 notes

Text

The Reality Behind Consent - A Study of How Affirmative Consent Discourses Treat the Topic with an Unrealistic Approach

Introduction

The word “consent”, on which the present article is centred, allows several interpretations. In its literal sense, the word is defined as the action of “agree to do something” or as a “permission for someone to do something” (Cambridge Learner’s Dictionary 2023). The meaning may seem simple at first glance; however, “consent” has a complex meaning, and it is the main topic of several discussions among scholars, especially when it is analysed in sexual encounters. Hall (1998, p.6) defined it as a “voluntary approval of what is done or proposed by another”; Hickman and Muehlenhard (1999, p.3) considered sexual consent as the “free verbal or nonverbal communication of a feeling of willingness”, and Beres (2007, p.98) defended “a version of consent defined as being ‘freely given'", which focuses on women’s and men’s willingness to engage in sexual relations and disconsiders the ideas of “valid” or “invalid” consent.

Around the discussions regarding consent and sexual violence, especially among university students, the concept of “affirmative consent” appears as a trend to be considered in law, policy and educational efforts. The model requires sexual consent to be a positive indication that people want to engage in sexual activities, instead of considering the absence of resistance or refusal (Beres and MacDonald, 2015). Following the same logic, California passed the Senate Bill 967 - Student safety: Sexual assault, which was labeled as the Affirmative Consent Bill in 2014. Beyond requiring “affirmative, conscious, and voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity” (De León et al., 2014, p. 1), it describes affirmative consent as a joint decision, stating: “it is the responsibility of each person involved in the sexual activity to ensure that he or she has the affirmative consent of the other or others to engage in the sexual activity” (De León et al., 2014, p. 1). The law also establishes that affirmative consent can be revoked at any time and cannot be assumed based on a dating relationship between the people involved, or on past sexual relations between them. With the aim of analysing “affirmative consent” measures / discourses and their techniques, the present article will focus on three well-known campaigns: “Consent is Sexy”, a mantra designed to highlight the pleasurable benefits of affirmative consent (Nash, 2019, p.200); the video “Tea and Consent” released by the Thames Valley Police in England in 2015, which claims that consent is “simple as tea” and “Sex Signals”, a program that presents skits focused on gender roles.

Contemporary campaigns related to affirmative consent discourses use it as a sexual regulation strategy to prevent sexual violence. Despite the effort to address the importance of agreement and permission, these campaigns result in a negative example of sexual regulation when sexual encounters are presented in an unrealistic way and when social factors are disconsidered. The issue is analysed by this article in three topics: consent defined as an enthusiastic “yes”, which leads to the definition of sex in the categories awesome or rape (Fischel, 2019); the concept of consent addressed as a simple matter that does not take into account gender norms and gendered power dynamics (MacKinnon 2006; Nash, 2019), and the mistaken premises that consent can ensure women’s freedom and equality (Beres and MacDonald, 2015) emphasizing what Gill (2007, 2008) describes as “postfeminist sensibility”, a concept that blends feminist and anti-feminist elements. The importance of dealing with this research topic in light of the existing theoretical foundations lies in the need to analyse consent issues, taking into account the complexities related to it, avoiding negative consequences that may be caused when the topic is simplified, such as young people feeling assaulted when sexual experiences are not satisfactory (Fischel, 2009), the invisibility of all cases where sex is consented but unwanted, a fact surrounded by gender and social norms (MacKinnon, 2006), and young women feeling blamed because they were unable to protect themselves from cases of sexual violence (Brady and Lowe, 2020).

Sex divided in the categories awesome and rape

Campaigns in several universities around affirmative consent are an important part of the intitutions’ effort to ensure ethical and legal sexual relations involving students. Many times, a key point promoted by these campaigns is the assertion that affirmative consent is a way to engage in legal sex and also a way to enhance pleasure; the topic is well-exemplified by the “Consent is Sexy'' campaign circulating in college campuses in the United States through posters, buttons, and shirts. According to Nash (2019, p.200), in this context, “affirmative consent is rebranded from a regulatory regime that distinguishes legal and illegal sex to a pleasure-maximization strategy.” It is important to notice that in the United States, the campaigns related to affirmative consent in universities emerged from the bases of Title IX, the most commonly used name for a civil rights law enacted in 1972, which states that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” The law bans sex discrimination in education which includes sexual harassment and rape; The Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) require colleges to have prevention and investigatory responsibilities when cases of sexual violence are reported. In case of failure, they may be investigated with the risk of losing federal financial assistance, while facing the critical gaze of both media and social activists. Currently, 357 cases of sexual violence are under investigation at elementary-secondary and post-secondary schools in the country (U.S Department of Education, 2023). The high number of cases reflect the alarming situation present in the institutions which boosts their efforts to defend legal sexual relations envolving students.

Despite of addressing the importance of sexual permission, campaigns related to affirmative may attribute other significances to the word “consent” leading to a simplistic interpretation of sexual relations. Fischel (2019, p.4) argues that a key problem of consent in sex politics is related to “a ridiculous definition of consent as enthusiastic, imaginative, creative yes-saying”, and also highlights the fact that bad sex, even if consensual, can be unwanted, unpleasant, and painful - an issue that is not addressed by consent. The author argues that “[conconsent-as-enthusiasm paradigm] divides sex into the categories awesome and rape and leaves unaccounted and unaddressed all the immiserating sex too many people, typically women, endure” (Fischel, 2019, p.4). By relating content to a “enthusiastic” permission, campaigns regarding affirmative consent leave behind cases of consensual sex without pleasure, which can be practised in many contexts, such as by people who are willing to experience sex in ways that might be painful or uncomfortable, and even by the ones who are having sex for the first time. Thus, affirmative consent discourses can attribute different meanings to consent and address sex relations in an unrealistic way.

The practice of dividing consensual sex as good sex and bad sex as rape, present in affirmative consent discourses, can also lead to serious consequences (even legal ones), if people consider all bad sexual experiences as sexual assault, and generalise the idea of consent. Fischel (2019) indicates worries related to the premise that the more consent is equated with enthusiasm and pleasure, the more students will feel sexually assaulted when sexual experiences do not go well. The author argues that the effort to deal seriously with sex without pleasure will have a disastrous effect if all unpleasant (but agreed) sex is considered sexual assault since consent were made more than it should be. Following the argument, professors Gersen and Suk (2016) criticize the “bureaucratic tendency” of merging sexual violence with ordinary sex, which, in their opinion, trivializes the serious problem of sexual assault, concluding that “the sex bureaucracy regulates ordinary sex, to the detriment of actually addressing sexual violence, and unfortunately erodes the legitimacy of efforts to fight sexual violence” (Gersen and Suk, 2016, p.946). Considering the presented arguments, consequences regarding the simplistic way that sexual relations are addressed by affirmative consent discourses are legitimate and need to be revised and transformed in order to avoid negative consequences. However, it is important to emphasize that unwanted sexual relations can happen even if consented, especially in situations where gender norms and inequalities are present (West, 2002; MacKinnon, 2006). Thus, cases of alleged sexual violence must be treated seriously and its specificities taken into account.

Beyond the practices for consent, scholars advocate for a better way to politicise sex. Fischel (2019) suggests the analysis of why people are consenting to unwanted sex and how the society can make sex better, while exposing the option of facilitating access to sexual information and health resources, as well as interrogating gender norms, rather than prioritising “best practices for consent”. In an article published in “The Washington Post”, the author Christine Emba advocates for a “new ethic” based on mutual concern that takes into account power differences regarding age, gender, experience, intoxication level, and expectations of commitment in sexual relations, concluding that “it is a much higher standard than consent. But consent was always the floor — it never should have been the ceiling” (The Washington Post, 2022). On the issue regarding prevention, Brady and Lowe (2020) affirm that a lack of understanding of the complexities of young women's sexual relationships is unhelpful when the aim is to reduce levels of violence. The scholars emphasise that simplistic understandings that overlook gendered power dynamics may, instead, reinforce women’s feeling of blame when they have been assaulted. On the same matter Kitzinger and Frith (1999) advocate that prevention programmes need to use empirical evidence of how refusals are expressed and understood, instead of idealising prescriptions that do not consider cultural conventions. After these considerations, it is important to point out that all the aspects addressed by the authors need to be considered in order to produce strategies and policies able to combat sexual violence in an effective way.

Consent taken as a simple matter

Campaigns regarding affirmative consent also address consent as something simple and many times explicitly related to the word “yes”, which once again represents sexual relations in a unrealistic way, leaving behind the fact that consent is permeated by social norms, social pressures, and gendered power dynamics. The issue is well exemplified by the video “Tea and Consent” released by the Thames Valley Police in England in 2015. By analogizing consent to drinking tea with consent in sexual relations, the video addresses an important message about permission with the following sentences: “if they say, ‘no, thank you', then don't make them tea at all”; “they did want tea, now they don't. (...) It's OK for people to change their mind. And you are still not entitled to watch them drink it”, and “unconscious people don't want tea”. However, by stating that consent is “simple as tea,” the video fails once it does not take into account complexities of gender inequality and social norms present in sexual conduct. The failure is expressed by the sentence “whether it’s tea or sex, consent is everything.” However, considering the social context in which the issue is present, consent is far from being everything. As well as affirmative consent, it can be forced, intimidated, and manipulated (MacKinnon, 2006, cited in Fischel, 2019). In her critique of the affirmative consent discourse, MacKinnon (2006, p.465) asserts that “under unequal conditions, many women acquiesce in or tolerate sex they cannot as a practical matter avoid or evade.” With this same logic, Brady and Lowe (2020) affirm that simplistic understandings that overlook norms present in sexual relations may leave young women with the feeling of blame for being unable to protect themselves. They claim that, when assuming sexual consent as a simple matter, those who find it difficult are considered incapable to follow clear instructions. Therefore, “those who are unable to negotiate sexual consent unproblematically are thus positioned as at least partially responsible for their behavior” (Brady and Lowe, 2020, p.86). Beyond addressing sexual relations in an unrealistic way, when consent is considered as a simple matter, it also makes invisible the situations where sex is consented but unwanted. Therefore, in an attempt to simplify a complex matter, affirmative consent discourses leave important social issues (that must be addressed by social reforms) behind.

As well as the video “Tea and Consent”, the popular sexual assault prevention program called “Sex Signals”, which is performed in several universities in the United States, is an example of an affirmative consent campaign that addresses consent as a simple matter. The program presents skits that combine theater, comedy and audience interaction, in order to implement sexual assault prevention. According to Catharsis Productions, the platform that offers the program, “it includes an intersectional lens to critique how stereotypes about sexuality and gender identity contribute to a culture that privileges some and objectifies others” (Catharsis Productions, 2023). The initiative succeeds in demonstrating that campus environment and interactions are marked by the complexity of ideas of gender roles and norms, but fails as well as the video “Tea and Consent”, when defending that these complex aspects can be simplified by affirmative consent. The issue is emphasised by Nash (2019, p.210) when the scholar asserts that “even as ‘Sex Signals’ insists on naming the tenacity of gender roles in shaping sexual encounters, it presumes that gender roles can be diffused simply through a mandate of receiving a ‘yes’— and that students can effectively be taught this in a thirty-minute skit.” Beyond simplifying social aspects, affirmative consent discourses also may be unrealistic regarding the use of verbal consent. Studies conducted by Hall (1998) and Jozkowski and Peterson (2014) show that college students are less likely to use verbal cues to express consent in sexual interactions than nonverbal cues, with no differences in frequency of usage by men and women. When considering relationship status, Jozkowski and Peterson (2014) and Humphreys (2007) found that, compared to single individuals, those in a relationship are less likely to use verbal cues to indicate sexual consent, which indicates that the more intimate the relationship, the less verbal cues of consent are used. Kitzinger and Frith (1999, p.310) claim that women find it difficult to just say “no” to sex because “saying immediate clear and direct 'no's (to anything) is not a normal conversational activity.” They suggest that, instead of saying “no”, women are acting in ways that normally are recognized as refusals in everyday life. According to the authors, the insistence of prevention strategies on the importance of saying “no” is counter-productive, since they are demanding women to engage in unreal conversations; furthermore, it allows rapists to claim that if the victim did not say no, then, she did not refuse to have sex. The discussion shows that verbal consent is not always part of traditional sexual interactions. Therefore, insisting in unrealistic approaches does not contribute to prevent sexual violence.

Does consent provide freedom and equality?

Affirmative consent discourses may present mistaken premises of freedom or equality when sexual interactions are simplified; such practice is flawed because it does not take into account important elements in societies, such as social and gender norms. Hence, the trouble with these notions becomes clear when the social contexts within which individuals engage in sex are finally considered (Beres and MacDonald, 2015). A woman might consent to sex she does not want because she fears her partner’s foul humour, or because she has been taught that it is her lot in life to do so. A particularly young woman or teenager may consent to unwanted sex because of social pressure, or because she does not want to hurt her partner`s pride (West, 2002); the use of verbal pressure or emotional manipulation can lead to sexual consent (Basile, 1999), and women also can engage in unwanted sex through the logic of an ‘economy of sex’, in which they exchange sexual relations for love or intimacy, elements considered essential for a relationship to be successful (Gravey, 2005). All these situations are examples of consensual sex but none of them have guaranteed women’s freedom or equality, which are complex concepts that can not be reached by a simplistic notion of consent, or unrealistic approaches of sexual relations.

Burkett and Hamilton (2012) developed a research study with eight young women (all university students) aged between 18 and 24 during mid-2010 in which they also found that sexual encounters are influenced by gendered discourses and norms. The authors defend that the issue around sexual consent must take into account what Gill (2007, 2008) describes as “postfeminist sensibility”, a concept that blends feminist and anti-feminist elements. They emphasised that the participants reflected the character of “postfeminist sensibilities” once they showed perceptions of women’s rights to sexual agency, but vilified their own and other women’s inabilities to control sexual encounters. The authors also claim that, unlike many sexual violence prevention policies portrayals, women are not innately free individuals who can just say no. Instead, they suggest that women are able to view themselves as empowered but continue to reproduce heteronormative norms. The view is well-exemplified by a participant called Lisa. She advocates that women must refuse verbally to unwanted sex (just say no), but reveals that even when she changes her mind about engaging in a sexual relation, she continues it in order to not feel guilty and to satisfy her partner: “it’s not like I did it because I really didn’t want to it’s just that I did it because it would make the other person happy – a selfless act. They’ve never been forceful or scary or anything so I’ve never felt like there was nothing I couldn’t get out of if I actually wanted to” (Burkett and Hamilton, 2012, p.822). When analysing this report, it is possible to notice that Lisa claims she had a choice, despite the fact that she was not able to change her mind; moreover, she may not have noticed the contradiction in her words. The research shows as well that the participants strongly adhere to risk-avoidance discourses; however, based on their sexual experiences, they affirmed that verbal communication during sex is not considered normal; instead of it, sexual intentions are judged by physical demonstrations, and by what is felt “in the moment”. The finding is exemplified by the testimony of a participant called Holly: “I found it sort of easier when you both just sort of don’t say anything and just go with that sort of in the moment kind of thing ...I think it’s more physical and telling by their body language that they want to have sex” (Burkett and Hamilton, 2012, p.821). According to the authors, this incongruity about what is perceived and what is done is present in the contradictions of the postfeminist sensibility concept. They claim that “it assumes a compulsory sexual agency (i.e. women are free to control and choose their sexual relations), regardless of the persistence of gendered sexual pressures, which in turn reframes coercive sexual encounters as the result of a woman’s lack of assertiveness” (Burkett and Hamilton, 2012, p.821). The findings reinforce that consent issues are not simple and absolutely do not ensure women's freedom and equality. Opposite to this premise, it is opportune to quote MacKinnon (2007) and her assert that an emancipated world would be one in which women have sex only when they want it.

Conclusion

This essay has shown that, despite the effort to address the importance of agreement in sexual relations, affirmative consent campaigns are a negative example of sexual regulation since they address sexual encounters in unrealistic ways, and do not take into account important factors around consent issues, such as social norms and gendered power dynamics. Campaigns that insist on the use of verbal cues for consent may not be effective because they consider sexual interactions in ways they do not normally happen (Hall, 1998; Peterson, 2014; Jozkowski and Peterson, 2014; Humphreys, 2007, and Kitzinger and Frith, 1999). Moreover, affirmative consent discourses disregard all the cases in which consent was forced, intimidated, or manipulated (MacKinnon, 2006).

To explain the main claim, the article considered the techniques and discourses used by affirmative consent strategies through three well-known campaigns: “Consent is Sexy”, which is very present in college campuses in the United States; the video “Tea and Consent”, a content released by the Thames Valley Police in England in 2015 that presents an analogy between consent and drinking tea, and the program “Sex Signals”, which promotes skits focused in gender roles that are performed in several universities in the United States. The article also analyses the three following aspects: the use of consent as a enthusiastic “yes” and the premise that defines sex as awesome or rape (Fischel, 2019); consent addressed as a simple matter, hence presented in a unrealistic way (MacKinnon 2006; Nash, 2019), and premises that consent ensures women’s freedom and equality (Beres and MacDonald, 2015).

Considering the analysis on the proposed topic, the article concludes that consent is not a simple matter; instead, it has many interpretations and complexities that must be considered in order to avoid negative consequences propagated by affirmative consent discourses, such as the feeling of harassment when a sex experience is not good (Fischel, 2019), the invisibility of cases when sex is consented but unwanted (MacKinnon, 2006), and the practice that blames victims of sexual violence (Brady and Lowe, 2020). Furthermore, when consent is considered as a simple issue, such as in the campaigns analysed by the article, gender norms and inequalities are ignored, instead of being considered with the aim to create actions for social change that could contribute to comprehensive and realistic approaches to sexual relations, healthier relationships, female empowerment, and to a more equitable society.

Bibliography

Basile, K.C., 1999. Rape by acquiescence: The ways in which women “give in” to unwanted sex with their husbands. Violence against women, 5(9), pp.1036-1058.

Beres, M.A. and MacDonald, J.E., 2015. Talking about sexual consent: Heterosexual women and BDSM. Australian Feminist Studies, 30(86), pp.418-432.

Beres, M.A., 2007. ‘Spontaneous’ sexual consent: An analysis of sexual consent literature. Feminism & Psychology, 17(1), pp.93-108.

Brady, G. and Lowe, P., 2020. ‘Go on, go on, go on’: Sexual consent, child sexual exploitation and cups of tea. Children & Society, 34(1), pp.78-92.

Burkett, M. and Hamilton, K., 2012. Postfeminist sexual agency: Young women’s negotiations of sexual consent. Sexualities, 15(7), pp.815-833.

Catharsis Productions. (n.d.). Sex Signals (Higher Education) - Sexual Assault Program for Colleges and Universities. [online] Available at: https://www.catharsisproductions.com/programs/sex-signals/ [Accessed 6 Aug. 2023].

De León, S., Jackson, S., Lowenthal, A., Ammiano, A., Beall, S., Cannella, S. and Wolk, S., 2014. Senate bill 967—Student safety: Sexual assault. California Legislative Information.

Emba, C. (2022). Consent is not enough. We need a new sexual ethic. [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/03/17/sex-ethics-rethinking-consent-culture/.

Fischel, J.J., 2019. Screw consent: A better politics of sexual justice. Univ of California Press.

Gavey, N. (2005). Just sex? : the cultural scaffolding of rape. London: Routledge.

Gersen, J. and Suk, J., 2016. The sex bureaucracy. California Law Review, pp.881-948.

Gill, R., 2007. Postfeminist media culture: Elements of a sensibility. European journal of cultural studies, 10(2), pp.147-166.

Gill, R., 2008. Culture and subjectivity in neoliberal and postfeminist times. Subjectivity, 25, pp.432-445.

Hall, D.S., 1998. Consent for sexual behavior in a college student population. Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, 1(10), pp.1-16.

Hickman, S.E. and Muehlenhard, C.L., 1999. “By the semi‐mystical appearance of a condom”: How young women and men communicate sexual consent in heterosexual situations. Journal of Sex Research, 36(3), pp.258-272.

Humphreys, T., 2007. Perceptions of sexual consent: The impact of relationship history and gender. Journal of Sex Research, 44(4), pp.307-315.

Jozkowski, K.N. and Peterson, Z.D., 2014. Assessing the validity and reliability of the perceptions of the consent to sex scale. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(6), pp.632-645.

Kitzinger, C. and Frith, H., 1999. Just say no? The use of conversation analysis in developing a feminist perspective on sexual refusal. Discourse & Society, 10(3), pp.293-316.

Mackinnon, C.A. 2006. Are women human? : and other international dialogues. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press.

MacKinnon, C.A., 2007. Women’s lives, men’s laws. Harvard University Press.

Nash, Jennifer C. "Pedagogies of desire." differences 30, no. 1 (2019): 197-227.

U.S. Department of Education (2021). Title IX and Sex Discrimination. Ed.gov. [online] doi:http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/tix_dis.html.

West, R., 2002. The harms of consensual sex. na.

www.consentiseverything.com. (n.d.). Consent is everything. [online] Available at: http://www.consentiseverything.com/.

www2.ed.gov. (2020). Pending Cases Currently Under Investigation at Elementary-Secondary and Post-Secondary Schools as of January 16, 2018 7:30am Search. [online] Available at: https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/investigations/open-investigations/tix.html.

0 notes

Text

A Claim of Freedom: The “Right to the City” Is a Gender Issue

When a woman leaves her home, many times the feeling of insecurity comes with her, as she avoids passing through dark streets and constantly looks back. In his concept of “right to the city”, Henri Lefebvre defended that it “should modify, concretize and make more practical the rights of the citizen, an urban dweller (citadin) and user of multiple services” (Lefebvre, Kofman and Lebas, 1996, p.34). Once related to all citizens, the concept involves an important aspect related to women’s access to their cities in societies where gender equality is far from being achieved. When women are afraid of leaving their homes, their “right to the city” becomes strictly limited. According to a survey published by Actionaid agency and developed by YouGov company in 2016, 86% of Brazilian women experienced harassment in public spaces (including public transport) and half of them had already been followed when walking in the streets.

The fear of leaving home leads the discussion about women’s rights to the city to the debate around public and private spheres (Kofman and Vacchelli, 2017), since in patriarchal societies, women have been reduced only to household chores, while men were associated to public activities, and historically this division arises deeper discussions: “private and public are not neutral categories, they are loaded terms that conceal other gender-related hierarchical dichotomies solidified in the different discursive regimes of social reproduction and production, passive and active, unpaid work and breadwinner, body and mind, nature and culture” (Kofman and Vacchelli, 2017, p.2). As well as their fears, these same “not neutral categories” walk with women in their claim for rights to the city, which was defined “like a cry and a demand” (Lefebvre, Kofman and Lebas 1996, p.158), and emphasized by me in this work as a claim for freedom in centuries of oppression. Many times, in an attempt to make their claim stronger, women create groups to promote interventions.

Women’s Walk

Aiming to improve girls and women’s access to the city, Instituto Caminhabilidade (Walkability Institute in english) developed in 2017 a project called “Caminhada das Mulheres” (Women’s Walk in english) that involves the aspects of walkability and gender, and identifies issues and possibilities for improving mobility and safety in public spaces. The deeper analysis developed by the project happened around Santana Terminal (that englobes Santana Metro Station and Santana Bus Station), which is the main point for public transport in the north region of São Paulo. The analysis was made by a group of 23 women with varied ages, levels of education and racial identities. The participants live in different neighborhoods around Terminal Santana, frequently use public transport and walk, and most of them take care of at least one person (children, elderly or disabled people).

The first part of the analysis happened in 2017, when the group identified in two walks and in one meeting the main issues around the Terminal and proposed solutions to be implemented by civil society, government and organizations. The major issues identified by them were related to security, emphasizing the feeling of unsafety during the night and at bus stations, and insecurity related to sexual harassment. The results confirm how the aspect of security is crucial for the “right to the city” and how women’s safety seems to be forgotten by the public authorities. “Feeling safe while alone within millions of strangers is the ultimate marker of a city’s livability” (1961, Jacobs, cited in Kern, 2021, p.93), which emphasizes that local governments should prioritize the agenda related to women's right to the city.

Image 1: This image shows part of Santana Terminal (Teixeira 2018).

The second part of the project took place between August 2018 and February 2019, when the group of women reviewed the solutions and started to put part of them into practice. The participants pasted posters around the area with content about the occurrence of sexual harassment and with information about women’s rights; organised a walk during the night caring flashlights with the aim to “highlight” the darkness in the region; wrote a statement called “The Bus Stop We Want” with solutions for the main problems in these places and pasted stickers with information about bus lines, such as the existence of a municipal law that allows women and elderly people to get off buses outside bus stops between 10 pm and 5 am.

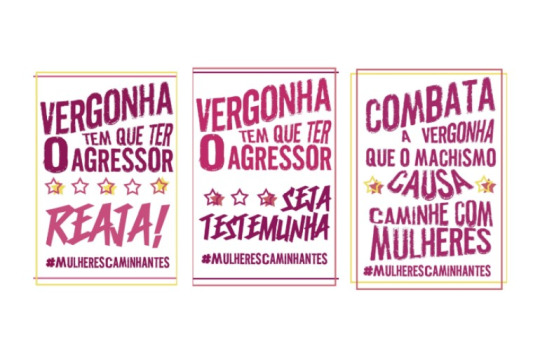

Images 2 - 6: These are the porters pasted by the participants around Santana Termina (França 2019).

Translations (PT - ENG):

Image 2 - It’s the aggressor who has to be embarrassed. Report it!

Image 3 - It’s the aggressor who has to be embarrassed. Do not blame the victim.

Image 4 - It’s the aggressor who has to be embarrassed. React!

Image 5 - It’s the aggressor who has to be embarrassed. Be a witness.

Image 6 - Fight against the embarrassment caused by sexism. Walk alongside women.

The importance of interventions promoted by volunteer groups from the perspective of women, aiming to help other women, is due to the fact that the streets were conceived and designed by men.

“The city has been set up to support and facilitate the traditional gender roles of men and with men’s experiences as the ‘norm,’ with little regard for how the city throws up roadblocks for women and ignores their day-to-day experience of city life. This is what I mean by the ‘city of men’” (Kern, 2021, p.6). The concept sums up how women and their issues were forgotten when men planned the city and emphasizes that they do not face the same problems. A dark street or a bus stop in a low-traffic area may not bother them; however it can make a woman change her route or even think twice before leaving home.

The interventions developed by the group dialogue with the concept of the “right to the city” once it reaches all the citizens in the urban space. Moreover, during all of the project, the participants changed their perspectives about the city and about its possibilities of access while changing the surroundings of Santana Terminal, which reflects the concept once again, as Harvey defines the “right to the city” as “the right to change ourselves by changing the city” (Harvey, 2008, p.23).

It is important to recognize how volunteer interventions, such as the “Women’s Walk” bring positive impacts for women and the society as a whole, but it is also important to point out that these interventions also need to be part of government strategies and initiatives. Where are the city councilors and the mayor of São Paulo while women feel unsafe of leaving their homes every night? What are they doing to solve this problem? When I think about these questions, the yelling gender inequality echoes in my head while Kern’s “city of men” concept continues to prevail. According to the Municipal Chamber of São Paulo, between 2016 and 2020, when the “Women’s Walk” happened, only 20% (11 in 55 representatives) of the city councilors were women. Nowadays, the percentage has increased to 24% (13 in 55 representatives) and represents the largest female presence ever formed in the legislative body of the city. The data shows that São Paulo, the largest city in Latin America, continues to be planned mostly by a male gaze.

Image 7: This image shows some of the women who were part of the project “Women’s Walk” in front of Santana Terminal (França 2019).

Despite the positive consequences brought by the “Women’s Walk”, it is a shame that they could not last for a long time. Advocating this aspect, the well-known activist Jane Jacobs presented the concept of “Eyes on The Street” (Jacobs, 1961) to explain the importance of a busy and vibrant street for the safety of a community. According to her, a street is safer when people are using and most enjoying it voluntarily and are least conscious of its policing. Therefore, she defended a substantial quantity of stores and other public spaces along the sidewalks where people would be watching around.

Forgotten by the local government, the next challenge for the group leading the “Women’s Walk” is to think about new strategies for the implementation of more lasting measures; setting the same interventions more often, and attempting to obtain support of other women through social media, which could help to increase the pressure on the city government for new measures.

Walkability Institute emphasized in its report that, despite the ephemeral character of the interventions, they contributed to the “discourse and the symbolic sphere of safe and sustainable spaces” (Gomes, Junqueira, Nunes and Sabino, 2019, p.29), and cited the concept of “discursive safe spaces,” developed by the professor Carolyn Whitzman, within her ideas for creating better cities for girls and women with citizen actions and anti violence messages.

After the analysis process, the Institute presented the report at a public audience in the Municipal Chamber of São Paulo. Unfortunately, the measures suggested were not adopted by the city government, but this fact did not reduce their importance and consequences, since the developed interventions changed the way participants and people affected by it perceive their “right to the city”. The project was also fundamental to highlight the struggles faced by girls and women in the region, and probably in many neighborhoods in São Paulo.

Conclusion

Women’s rights to the city are brutally contested for gender issues. With her struggles forgotten by the men who planned the city and ignored by governments, they find in mutual help (sorority) a way to organize themselves to set interventions in attempting to guarantee their rights. Sadly, it is not enough to challenge old structures that have excluded them for a long time, their interventions must be long-lasting so that their rights will not be easily violated again. Despite many difficulties, they continue to change themselves while changing the city, in a persistent claim for freedom.

Bibliography:

ActionAid. (n.d.). Em pesquisa da ActionAid, 86% das brasileiras ouvidas dizem já ter sofrido assédio em espaços urbanos. [online] Available at: https://actionaid.org.br/na_midia/em-pesquisa-da-actionaid-86-das-brasileiras-ouvidas-dizem-ja-ter-sofrido-assedio-em-espacos-urbanos/

Câmara Municipal de São Paulo. (2021). Artigo: Como fazer do Parlamento municipal um ambiente mais igualitário? por Milton Leite. [online] Available at: https://www.saopaulo.sp.leg.br/blog/artigo-como-fazer-do-parlamento-municipal-um-ambiente-mais-igualitario-por-milton-leite/ [Accessed 17 Jun. 2023].

Câmara Municipal de São Paulo. (n.d.). Mulheres. [online] Available at: https://www.saopaulo.sp.leg.br/especiaiscmsp/especial-mulheres [Accessed 17 Jun. 2023].

David Harvey (2008). The Right to the City. [online] New Left Review. Available at: https://newleftreview.org/issues/II53/articles/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city.

França, P 2019, posters used by the project “Women’s Walk”, image, viewed 18 Jun 2023, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SVN-Jrm0TkFLUKzGysN6fniq1M5W6gaF/view.

França, P 2019, women who were part of the project “Women’s Walk, image, viewed 18 Jun 2023, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SVN-Jrm0TkFLUKzGysN6fniq1M5W6gaF/view.

Gomes, K. Junqueira, A. Nunes, C. and Sabino, L. (2019). Como melhorar a segurança

e a mobilidade de meninas e mulheres? A experiência do projeto Santana Segura

pelas Mulheres e para as Mulheres. [online] São Paulo. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SVN-Jrm0TkFLUKzGysN6fniq1M5W6gaF/view [Accessed 17 June 2023].

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York: Random House.

Kern, L. (2020). FEMINIST CITY : claiming space in a man-made world. S.L.: Verso Books.

Lefebvre, H., Kofman, E. and Lebas, E. (1996). Writings on cities. Cambridge, Mass, Usa: Blackwell Publishers.

Teixira, R 2019, Santana Terminal, image, Flickr, viewed 18 Jun 2023, https://www.flickr.com/photos/29578076@N08/41030768600.

Vacchelli, E. and Kofman, E. (2017) Towards an inclusive and gendered right to the city’. Available at:https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.lib.bbk.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S0264275117312040#bb0070 (Accessed: 17 June 2023).

0 notes

Text

Teias de aranha, lagarta frita e prato extra: veja sete tradições de Natal estranhas ao redor do mundo

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/fotos/teias-de-aranha-lagarta-frita-e-prato-extra-veja-sete-tradicoes-de-natal-estranhas-ao-redor-do-mundo-20122022#/foto/1

0 notes

Text

Reprimidas por tutela masculina, mulheres no Catar fogem em busca de liberdade e segurança

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/reprimidas-por-tutela-masculina-mulheres-no-catar-fogem-em-busca-de-liberdade-e-seguranca-15122022

0 notes

Text

ONU revela que mais de cinco mulheres foram mortas a cada hora por um familiar em 2021

0 notes

Text

Qual é a intenção da Coreia do Norte ao fazer testes com mísseis?

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/qual-e-a-intencao-da-coreia-do-norte-ao-fazer-testes-com-misseis-19112022

0 notes

Text

Entenda o que é o artigo 5º da Otan e como se relaciona com míssil que caiu na Polônia

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/entenda-o-que-e-o-artigo-5-da-otan-e-como-se-relaciona-com-missil-que-caiu-na-polonia-16112022

0 notes

Text

Leis do Irã deixam mulheres com ‘metade’ dos direitos dos homens

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/leis-do-ira-deixam-mulheres-com-metade-dos-direitos-dos-homens-11112022

0 notes

Text

Ucraniana conhecida como Joana d'Arc se casa com colega militar que conheceu na guerra contra a Rússia

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/fotos/ucraniana-conhecida-como-joana-darc-se-casa-com-colega-militar-que-conheceu-na-guerra-contra-a-russia-28102022#/foto/1

0 notes

Text

Rei Charles 3º promete servir com 'lealdade e amor' em primeiro discurso como monarca

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/rei-charles-3-promete-servir-com-lealdade-e-amor-em-primeiro-discurso-como-monarca-09092022

0 notes

Text

Afegã denuncia ex-oficial talibã por estupro e casamento forçado em vídeo que viralizou na internet

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/afega-denuncia-ex-oficial-taliba-por-estupro-e-casamento-forcado-em-video-que-viralizou-na-internet-01092022

0 notes

Text

25 anos sem Diana: veja 7 teorias da conspiração sobre a tragédia que matou a princesa

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/fotos/25-anos-sem-diana-veja-7-teorias-da-conspiracao-sobre-a-tragedia-que-matou-a-princesa-31082022#/foto/1

0 notes

Text

Rússia X Ucrânia: quem sai fortalecido após seis meses de guerra?

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/fotos/russia-x-ucrania-quem-sai-fortalecido-apos-seis-meses-de-guerra-24082022#/foto/1

0 notes

Text

Conflito completa seis meses com Ucrânia à espera de 'algo feio' da Rússia em guerra sem horizontes

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/conflito-completa-seis-meses-com-ucrania-a-espera-de-algo-feio-da-russia-em-guerra-sem-horizontes-24082022

0 notes

Text

Sonho americano: conheça mitos e verdades sobre o processo para tirar o green card

https://noticias.r7.com/internacional/sonho-americano-conheca-mitos-e-verdades-sobre-o-processo-para-tirar-o-green-card-08082022

0 notes