Text

Twitter Labeled 300000 US Election Tweets [Infographic]

Twitter Labeled 300000 US Election Tweets [Infographic]; Twitter Labeled 300,000 U.S. Election Tweets [Infographic]. Niall McCarthyContributor. Opinions expressed by Forbes Contributors are their own.; Google Alert - site:forbes.com infographic; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2020/11/13/twitter-labeled-300000-us-election-tweets-infographic/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjI0NmZkNTNhM2VmNTA0ZGI6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNGs0HJeER2jcyfdo98UHg9DgFsxsA; ; November 14, 2020 at 04:11AM

0 notes

Text

The Nightmare Pandemic Economy Joe Biden Is Inheriting, in 5 Charts

The Nightmare Pandemic Economy Joe Biden Is Inheriting, in 5 Charts; The following five charts show what Biden and his Vice President-elect, Kamala Harris, are up against as they prepare to take the oaths of office.; Google Alert - site:time.com chart; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://time.com/5911723/biden-economy-pandemic/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjE4ZDc4MWZmMTAyNjc0ZTY6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNG77JHpO-2KrtTuDlpS1XKr83zpGA; ; November 14, 2020 at 03:42AM

0 notes

Text

Australia's newspaper ownership is among the most concentrated in the world

Australia's newspaper ownership is among the most concentrated in the world; Ownership of Australia's newspapers is one of the most concentrated in the world, but changes in how media companies measure their audience ...; Google Alert - site:theguardian.com/news/datablog; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2020/nov/14/australias-news-media-is-among-the-most-concentrated-in-the-world-and-its-not-getting-any-better&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjU4YzYwMDQ5MjZjZmU1NWM6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNGweIrMVLLQFt93Rn4qXsIySn57SA; ; November 13, 2020 at 06:43PM

0 notes

Text

Covid fears are disrupting the $30 billion global fur industry

Covid fears are disrupting the $30 billion global fur industry; Minks are an important part of the global fur trade, valued from $24 billion (paywall) to $33 billion (paywall) in 2018, depending on the source.; Google Alert - site:qz.com source; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://qz.com/1932994/covid-transmission-fears-are-disrupting-the-mink-fur-industry/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjZkZmFjNDZiMWQwMDI1YzY6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNG8EBSV0nXkLoimXykInLRllsyNgg; ; November 13, 2020 at 05:33PM

0 notes

Text

The argument for a tax on people who work from home

The argument for a tax on people who work from home; But on social media, early critics of the idea have attacked its source. Isn't this rich coming from Deutsche Bank, they suggest, the recipient of indirect ...; Google Alert - site:qz.com source; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://qz.com/work/1932442/why-we-should-tax-people-who-work-from-home/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjZkZmFjNDZiMWQwMDI1YzY6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNE8ixRNY-2FiEuULUgp9ocyczFckA; ; November 13, 2020 at 05:33PM

0 notes

Text

Understanding how 2020’s election polls performed and what it might mean for other kinds of survey work

Understanding how 2020’s election polls performed and what it might mean for other kinds of survey work;

(Brianna Soukup/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images)

Taken in the aggregate, preelection polls in the United States pointed to the strong likelihood that Democrat Joe Biden would pick up several states that Hillary Clinton lost in 2016 and, in the process, win a popular and electoral vote majority over Republican President Donald Trump. That indeed came to pass. But the election was much closer than polls suggested in several battleground states (e.g., Wisconsin) and more decisive for Trump elsewhere (e.g., Ohio). Democrats also were disappointed at failing to pick up outright control of the U.S. Senate – though it remains a possibility – and at losing seats in the U.S. House and several state legislatures.

Many who follow public opinion polls are understandably asking how these outcomes could happen, especially after the fairly aggressive steps the polling community took to understand and address problems that surfaced in 2016. We are asking ourselves the same thing. In this post, we’ll take a preliminary shot at answering that question, characterizing the nature and scope of the 2020 polling errors and suggesting some possible causes. We’ll also consider what this year’s errors might mean for issue-focused surveys, though it will be many months before the industry will be able to collect all the data necessary to come to any solid conclusions.

Preelection polls in the United States pointed to the likelihood that Joe Biden would win a popular and electoral vote majority over Donald Trump. That indeed came to pass. But the election was much closer than polls suggested in several battleground states and more decisive for Trump elsewhere.

Before talking about what went wrong, there are a couple of important caveats worth noting. First, given the Democratic-leaning tendency to vote by mail this year and the fact that mail votes are counted later in many places, the size of the polling errors – especially at the national level – will likely end up being smaller than they appeared on election night. Even this week, vote counting continues and estimates of polling errors have shrunk somewhat in many battleground states. It’s also important to recognize that not all states suffered a polling misfire. In many important states that Biden won (at least based on current vote totals), including Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Minnesota, New Mexico, Nevada and Virginia, polls gave a solid read of the contest.

All that said, it’s clear that national and many state estimates were not just off, but off in the same direction: They favored the Democratic candidate. To measure by how much, we compared the actual vote margins between Republicans and Democrats – both nationally and at the state level – with the margins in a weighted average of polls from FiveThirtyEight.com. Looking across the 12 battleground states from the upper Midwest (where many polls missed the mark) to the Sun Belt and Southwest (where many were stronger), polls overestimated the Democratic advantage by an average of about 4 percentage points. When looking at national polls, the Democratic overstatement will end up being similar, about 4 points, depending on the final vote count. That means state polling errors are about the same as in 2016, while the national polling error is slightly larger, at least as of today. Even so, the national polling error of 2020 appears to be similar to the average errors for election polls over the past 12 presidential elections.

The fact that the polling errors were not random, and that they almost uniformly involved underestimates of Republican rather than Democratic performance, points to a systematic cause or set of causes. At this early point in the post-election period, the theories about what went wrong fall roughly into four categories, each of which has different ramifications for the polling industry.

Partisan nonresponse

The suggested problem

According to this theory, Democratic voters were more easily reachable and/or just more willing than Republican voters to respond to surveys, and routine statistical adjustments fell short in correcting for the problem. A variant of this: The overall share of Republicans in survey samples was roughly correct, but the samples underrepresented the most hard-core Trump supporters in the party. One possible corollary of this theory is that Republicans’ widespread lack of trust in institutions like the news media – which sponsors a great deal of polling – led some people to not want to participate in polls.

Is this mainly an election polling problem, or would this be of wider concern to issue pollsters as well?

Sadly, the latter. If polls are systematically underrepresenting some types of conservatives or Republicans, it has ramifications for surveys that measure all kinds of behaviors and issues, from views on the coronavirus pandemic to attitudes toward climate change. Issue polling doesn’t require the kind of 51%-49% precision of modern presidential election polling, of course, but no pollster wants a systematic skew to their data, even if it’s “only” 5 percentage points.

What could we do to fix it?

A straightforward fix to the problem of underrepresenting Trump supporters would be to increase efforts to recruit conservatives and Republicans to polls; increase the statistical weight of those already in the survey to match their share of the population (a process known as “weighting”); or both. Many polls this year weighted on party registration, 2016 vote or self-identified partisanship, but still underestimated GOP support.

The challenge here is twofold. The first is in estimating the correct share of conservatives and Republicans in the population, since, unlike age, gender and other demographic characteristics, there are no timely, authoritative benchmarks on political orientation. Second, just getting the overall share of Republicans in the poll correct may be insufficient if those who are willing to be interviewed are bad proxies for those who are not willing (e.g., more strongly conservative) – in which case a weighting adjustment within partisan groups may be needed.

‘Shy Trump’ voters

The suggested problem

According to this theory, not all poll respondents who supported Trump may have been honest about their support for him, either out of some sort of concern about being criticized for backing the president or simply a desire to mislead. Considerable research, including by Pew Research Center, has failed to turn up much evidence for this idea, but it remains plausible.

The fact that polls this year underestimated support for other, less controversial Republican candidates – sometimes by more than they underestimated support for Trump – suggests that the “shy Trump” hypothesis may not explain very much of the problem.

Is this mainly an election polling problem, or would this be of wider concern to issue pollsters as well?

This would pose a challenge for measuring attitudes about the president in any venue. But if it was limited to the current president, it would not have lasting impact. Polls on issues that are less sensitive might be less affected.

What could we do to fix it?

In the electoral context, this is a difficult problem to fix. Pollsters have experimented with approaches to doing so, such as asking respondents how their friends and neighbors planned to vote (in addition to asking respondents how they themselves planned to vote) and then using answers to these questions to adjust their forecasts. But the efficacy of these methods is still uncertain.

Still, the fact that polls this year underestimated support for other, less controversial Republican candidates – sometimes by more than they underestimated support for Trump – suggests that the “shy Trump” hypothesis may not explain very much of the problem.

Turnout error A: Underestimating enthusiasm for Trump

The suggested problem

Election polls, as opposed to issue polling, have an extra hurdle to clear in their attempt to be accurate: They have to predict which respondents are actually going to cast a ballot and then measure the race only among this subset of “likely voters.” Under this theory, it’s possible that the traditional “likely voter screens” that pollsters use just didn’t work as a way to measure Trump voters’ enthusiasm to turn out for their candidate. In this case, surveys may have had enough Trump voters in their samples, but not counted enough of them as likely voters.

Is this mainly an election polling problem, or would this be of wider concern to issue pollsters as well?

If the main problem this year was a failure to anticipate the size of Republican turnout, the accuracy of issue polls would be much less affected. It would suggest that survey samples may already adequately represent Americans of all political persuasions but still struggle to properly anticipate who will actually turn out to vote, which we know is quite difficult. Fortunately, the eventual availability of state voter records matched to many election surveys will make it possible to assess the extent to which turnout differences between Trump and Biden supporters explain the errors.

What could we do to fix it?

Back to the mines on reinventing likely voter scales.

Turnout error B: The pandemic effect

The suggested problem

The once-in-a-generation coronavirus pandemic dramatically altered how people intended to vote, with Democrats disproportionately concerned about the virus and using early voting (either by mail or in person) and Republicans more likely to vote in person on Election Day itself. In such an unusual year – with so many people voting early for the first time and some states changing their procedures – it’s possible that some Democrats who thought they had, or would, cast a ballot did not successfully do so. A related point is that Trump and the Republican Party conducted a more traditional get-out-the-vote effort in the campaign’s final weeks, with large rallies and door-to-door canvassing. These may have further confounded likely voter models.

Is this mainly an election polling problem, or would this be of wider concern to issue pollsters as well?

To the extent that polls were distorted by the pandemic, the problems may be confined to this moment in time and this specific election. Issue polling would be unaffected.

To the extent that polls were distorted by the pandemic, the problems may be confined to this moment in time and this specific election. Issue polling would be unaffected. The pandemic may have created greater obstacles to voting for Democrats than Republicans, a possibility that polls would have a hard time assessing. These are not problems we typically confront with issue polling.

What could we do to fix it?

It’s possible that researchers could develop questions, such as on knowledge of the voting process, that could help predict whether the drop-off between intention to vote and having successfully cast a ballot is higher for some voters than others – for instance, whether a voter’s mailed ballot is successfully counted or may be rejected for some reason. Treating all early voters as definitely having voted and all Election Day voters as only possible voters is a potential mistake that can be avoided.

Conclusion

As we begin to study the performance of 2020 election polling in more detail, it’s also entirely possible that all of these factors contributed in some way – a “perfect storm” that blew the polls off course.

Pew Research Center and other polling organizations will devote a great deal of effort to understanding what happened. Indeed, we have already begun to do so. We’ll conduct a review of our own polling, as well as a broader analysis of the polls, and we’ll participate in a task force established at the beginning of this year by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) to review election poll performance, as happened in 2016. This effort will take time. Relevant data on voter turnout will take months to compile. But make no mistake: We are committed to understanding the sources of the problem, fixing them and being transparent along the way.

Scott Keeter is a senior survey advisor at Pew Research Center.

Claudia Deane is vice president of research at Pew Research Center.

; Blog (Fact Tank) – Pew Research Center; https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/13/understanding-how-2020s-election-polls-performed-and-what-it-might-mean-for-other-kinds-of-survey-work/; https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FT_20.11.12_Polling_feature.jpg?w=1200&h=628&crop=1; November 13, 2020 at 12:07PM

0 notes

Text

America is exceptional in the nature of its political divide

America is exceptional in the nature of its political divide;

In his first speech as president-elect, Joe Biden made clear his intention to bridge the deep and bitter divisions in American society. He pledged to look beyond red and blue and to discard the harsh rhetoric that characterizes our political debates.

It will be a difficult struggle. Americans have rarely been as polarized as they are today.

The studies we’ve conducted at Pew Research Center over the past few years illustrate the increasingly stark disagreement between Democrats and Republicans on the economy, racial justice, climate change, law enforcement, international engagement and a long list of other issues. The 2020 presidential election further highlighted these deep-seated divides. Supporters of Biden and Donald Trump believe the differences between them are about more than just politics and policies. A month before the election, roughly eight-in-ten registered voters in both camps said their differences with the other side were about core American values, and roughly nine-in-ten – again in both camps – worried that a victory by the other would lead to “lasting harm” to the United States.

The U.S. is hardly the only country wrestling with deepening political fissures. Brexit has polarized British politics, the rise of populist parties has disrupted party systems across Europe, and cultural conflict and economic anxieties have intensified old cleavages and created new ones in many advanced democracies. America and other advanced economies face many common strains over how opportunity is distributed in a global economy and how our culture adapts to growing diversity in an interconnected world.

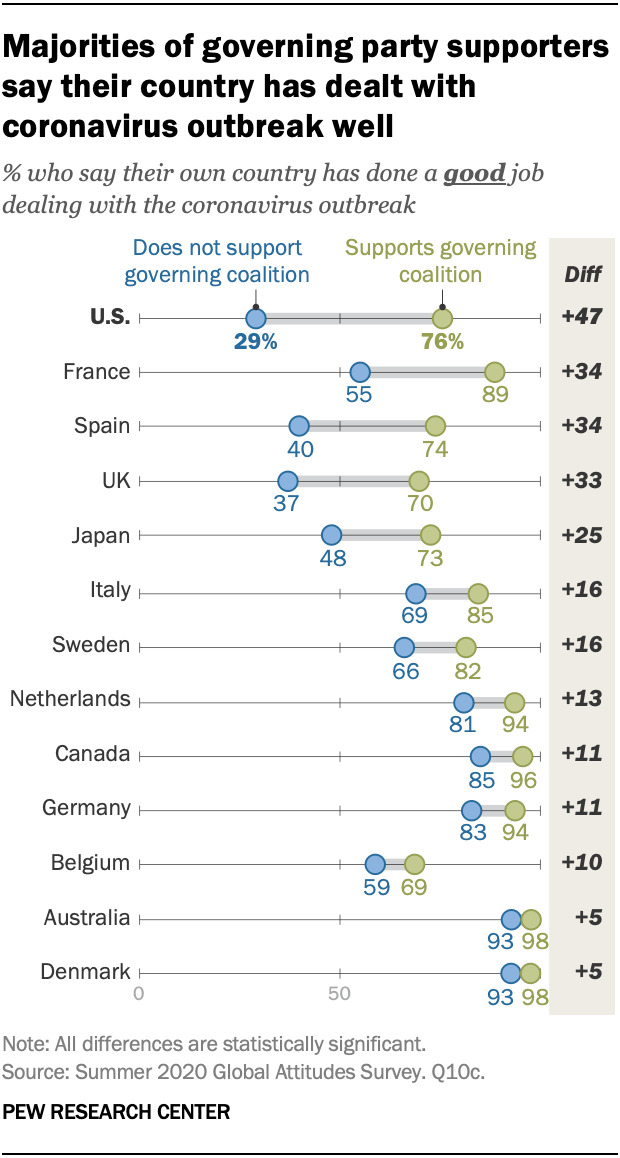

But the 2020 pandemic has revealed how pervasive the divide in American politics is relative to other nations. Over the summer, 76% of Republicans (including independents who lean to the party) felt the U.S. had done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, compared with just 29% of those who do not identify with the Republican Party. This 47 percentage point gap was the largest gap found between those who support the governing party and those who do not across 14 nations surveyed. Moreover, 77% of Americans said the country was now more divided than before the outbreak, as compared with a median of 47% in the 13 other nations surveyed.

Much of this American exceptionalism preceded the coronavirus: In a Pew Research Center study conducted before the pandemic, Americans were more ideologically divided than any of the 19 other publics surveyed when asked how much trust they have in scientists and whether scientists make decisions solely based on facts. These fissures have pervaded nearly every aspect of the public and policy response to the crisis over the course of the year. Democrats and Republicans differ over mask wearing, contact tracing, how well public health officials are dealing with the crisis, whether to get a vaccine once one is available, and whether life will remain changed in a major way after the pandemic. For Biden supporters, the coronavirus outbreak was a central issue in the election – in an October poll, 82% said it was very important to their vote. Among Trump supporters, it was easily the least significant among six issues tested on the survey: Just 24% said it was very important.

Why is America cleaved in this way? Once again, looking across other nations gives us some indication. The polarizing pressures of partisan media, social media, and even deeply rooted cultural, historical and regional divides are hardly unique to America. By comparison, America’s relatively rigid, two-party electoral system stands apart by collapsing a wide range of legitimate social and political debates into a singular battle line that can make our differences appear even larger than they may actually be. And when the balance of support for these political parties is close enough for either to gain near-term electoral advantage – as it has in the U.S. for more than a quarter century – the competition becomes cutthroat and politics begins to feel zero-sum, where one side’s gain is inherently the other’s loss. Finding common cause – even to fight a common enemy in the public health and economic threat posed by the coronavirus – has eluded us.

Over time, these battles result in nearly all societal tensions becoming consolidated into two competing camps. As Ezra Klein and other writers have noted, divisions between the two parties have intensified over time as various types of identities have become “stacked” on top of people’s partisan identities. Race, religion and ideology now align with partisan identity in ways that they often didn’t in eras when the two parties were relatively heterogenous coalitions. In their study of polarization across nations, Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue argue that polarization runs particularly deep in the U.S. in part because American polarization is “especially multifaceted.” According to Carothers and O’Donohue, a “powerful alignment of ideology, race, and religion renders America’s divisions unusually encompassing and profound. It is hard to find another example of polarization in the world,” they write, “that fuses all three major types of identity divisions in a similar way.”

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with disagreement in politics, and before we get nostalgic for a less polarized past it’s important to remember that eras of relatively muted partisan conflict, such as the late 1950s, were also characterized by structural injustice that kept many voices – particularly those of non-White Americans – out of the political arena. Similarly, previous eras of deep division, such as the late 1960s, were far less partisan but hardly less violent or destabilizing. Overall, it’s not at all clear that Americans are further apart from each other than we’ve been in the past, or even that we are more ideologically or affectively divided – that is, exhibiting hostility to those of the other party – than citizens of other democracies. What’s unique about this moment – and particularly acute in America – is that these divisions have collapsed onto a singular axis where we find no toehold for common cause or collective national identity.

Americans both see this problem and want to address it. Overwhelming majorities of both Trump (86%) and Biden (89%) supporters surveyed this fall said that their preferred candidate, if elected, should focus on addressing the needs of all Americans, “even if it means disappointing some of his supporters.”

In his speech, President-elect Biden vowed to “work as hard for those who didn’t vote for me as those who did” and called on “this grim era of demonization in America” to come to an end. That’s a sentiment that resonates with Americans on both sides of the fence. But good intentions on the part of our leaders and ourselves face serious headwinds in a political system that reinforces a two-party political battleground at nearly every level.

Richard Wike is director of global attitudes research at Pew Research Center.

; Blog (Fact Tank) – Pew Research Center; https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/13/america-is-exceptional-in-the-nature-of-its-political-divide/; ; November 13, 2020 at 09:10AM

0 notes

Text

Dhanteras 2020: Can bitcoin, other cryptocurrencies replace gold?

Dhanteras 2020: Can bitcoin, other cryptocurrencies replace gold?; Since the spread of Covid-19 in India, bitcoin has outperformed every other asset class, including gold, giving a return of nearly 160% since April.; Google Alert - site:qz.com source; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://qz.com/india/1931811/dhanteras-2020-can-bitcoin-other-cryptocurrencies-replace-gold/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjZkZmFjNDZiMWQwMDI1YzY6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNEOm7QP8wPmYUPrqwe0UMpVYDuyrA; ; November 13, 2020 at 12:59AM

0 notes

Text

Vote for the WSJ House of the Week: November 12

Vote for the WSJ House of the Week: November 12; Will it be a base for boating in Florida, a restored Arts and Crafts home on the Massachusetts coast or an Italian villa in Montecito?; Google Alert - site:graphics.wsj.co...; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://graphics.wsj.com/photo-poll/house-of-the-week-11122020&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGmFhNjQ1OTdmMzA1MTVmNDE6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNGQvBKrf0X9zRpQZnNpk8yFywtlOg; ; November 13, 2020 at 12:26AM

0 notes

Text

US Covid-19 Hospitalizations Soar To Record High [Infographic]

US Covid-19 Hospitalizations Soar To Record High [Infographic]; Coronavirus cases have been skyrocketing across the United States in recent weeks and the number of new infections surpassed 140,000 on ...; Google Alert - site:forbes.com infographic; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2020/11/12/us-covid-19-hospitalizations-soar-to-record-high-infographic/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjI0NmZkNTNhM2VmNTA0ZGI6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNE-Jx_31zYIMg22CEhfPweAn8uHSA; ; November 12, 2020 at 09:46PM

0 notes

Text

The Weeknd To Play Super Bowl LV Halftime Show

The Weeknd To Play Super Bowl LV Halftime Show; ... album Starboy at no. 2); and his ubiquitous hit track “Blinding Lights” has spent a record-breaking 46 weeks on Billboard's Pop Songs airplay chart.; Google Alert - site:time.com chart; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://time.com/5910989/the-weeknd-super-bowl-lv-halftime-show/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjE4ZDc4MWZmMTAyNjc0ZTY6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNGRcb30u1tiqZzxwFxwlVuVMrUNQg; ; November 12, 2020 at 09:32PM

0 notes

Text

How people around the world see the World Health Organization’s initial coronavirus response

How people around the world see the World Health Organization’s initial coronavirus response;

World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus leaves a ceremony in Geneva for the restarting of the city’s Jet d’Eau fountain in June 2020. The fountain had been shut off due to concerns over the coronavirus outbreak. (Fabrice Coffrini/AFP via Getty Images)

The World Health Organization (WHO) has played a controversial role in the global response to the coronavirus pandemic. U.S. President Donald Trump has accused the organization of being too close to China and moved to withdraw the United States from it. At the same time, the WHO is helping coordinate the international rollout of potential vaccines and treatments for COVID-19.

As the WHO holds its 73rd World Health Assembly – remotely this year, due to the pandemic – here is a look at how people in 14 advanced economies viewed the organization’s initial COVID-19 response, based on surveys conducted in June through August by Pew Research Center.

This analysis focuses on how people in 14 advanced economies viewed the World Health Organization’s response to the coronavirus outbreak earlier this year.

The analysis is based on nationally representative surveys of 14,276 adults conducted from June 10 to Aug. 3, 2020. (It’s important to note that this was a time when the pandemic appeared to be receding across Europe and much of the U.S.) Surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in the U.S., Canada, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK, Australia, Japan and South Korea. Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

The study was conducted in countries where nationally representative telephone surveys are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

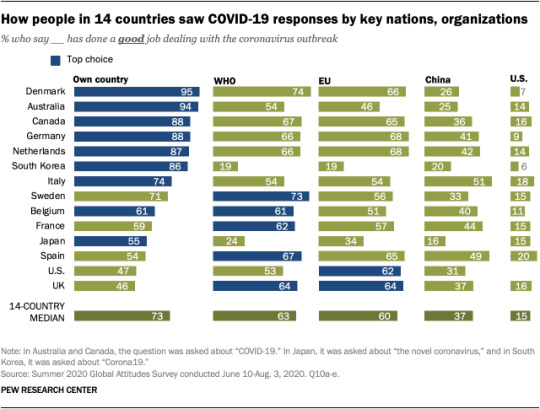

In most surveyed countries, majorities approved of the WHO’s handling of the pandemic, though there were some notable exceptions. A median of 63% of adults across 14 nations said this summer that the WHO had done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak. In 12 of these countries, half or more thought the WHO had managed the pandemic well.

Japan and South Korea – two early hotspots for the virus – were notable outliers. Only about a fifth of South Koreans (19%) and a quarter of Japanese (24%) were convinced the WHO had dealt with the pandemic well. In May, South Korean President Moon Jae-In pushed for the organization to be tougher on member nations, particularly with regard to sharing data about the virus. And Japanese Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso has panned the organization for its close ties to China, a nation viewed negatively by nearly nine-in-ten Japanese.

People in most surveyed countries were more likely to approve of their own nation’s handling of the pandemic than the WHO’s response. But that wasn’t the case everywhere. In Sweden, Belgium, France and the U.S., similar shares said their country and the WHO had done a good job. Elsewhere, more said the WHO had handled the outbreak well than said the same of their own country. (The survey was conducted in summer, before a second surge in coronavirus cases began across Europe.) In the UK, fewer than half (46%) said their own country had done a good job dealing with the virus, but 64% said the same about the WHO. Similarly, in Spain, 54% said their country had dealt with the virus well, but two-thirds said the same of the WHO.

Americans have grown slightly more positive about the WHO’s handling of the pandemic. Only 53% of Americans said this summer that the organization had handled the outbreak well, but that represented an increase since the spring, when only 46% said this.

Democrats and independents who lean Democratic were more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to assess the WHO’s pandemic response positively. Seven-in-ten Democrats said the organization had done a good job dealing with the outbreak, compared with only 32% of Republicans. There was a similar partisan divide in the spring, but the share of Democrats who rated the WHO’s response positively increased by 8 percentage points by summer (from 62% to 70%).

In all surveyed nations, those who have a favorable opinion of the United Nations were more likely to think the WHO – which is part of the UN – had done a good job dealing with the virus. In Australia, for example, 69% of adults with a favorable view of the UN saw the WHO’s handling of the pandemic as effective, compared with only 26% of those with an unfavorable opinion of the UN.

In some countries, including the U.S., political ideology and support for political parties were also connected with views of the WHO. In half the countries surveyed, those on the left of the ideological spectrum were more likely than those on the right to think the WHO had handled the pandemic well.

Similarly, Europeans who support left-wing populist parties were more likely to think the WHO had done a good job managing the outbreak when compared with those who do not support these parties. Conversely, supporters of some right-wing populist parties were less likely than nonsupporters to think the organization’s response to the coronavirus outbreak had been effective.

In most surveyed countries, women and younger adults were more likely to say the WHO had handled the virus well. The gender divide was largest in Italy, where two-thirds of women said this summer that the organization had been effective in dealing with the pandemic, compared with fewer than half of men (44%).

Similarly, in nine countries, adults ages 18 to 29 were more likely than those 50 and older to say the WHO had done a good job dealing with the outbreak. For example, in the U.S., 68% of younger adults said the WHO’s response to the outbreak had been effective, compared with only 49% of older adults.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

Mara Mordecai is a research assistant focusing on global attitudes research at Pew Research Center.

; Blog (Fact Tank) – Pew Research Center; https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/12/how-people-around-the-world-see-the-world-health-organizations-initial-coronavirus-response/; https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FT_20.11.10_WHO_covid-Featured-image.jpg?w=1200&h=628&crop=1; November 12, 2020 at 01:47PM

0 notes

Text

Trump ICE deporting African asylum seekers before Biden gets in

Trump ICE deporting African asylum seekers before Biden gets in; Asylum seekers from Cameroon, Angola and DR Congo are among those forced onto a plane and expelled from the US.; Google Alert - site:qz.com source; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://qz.com/africa/1932261/trump-ice-deporting-african-asylum-seekers-before-biden-gets-in/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjZkZmFjNDZiMWQwMDI1YzY6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNFMhLWLf3WQ1rr9BlGt_1V4Ru3WGQ; ; November 12, 2020 at 07:20AM

0 notes

Text

How Often Has President Trump Played Golf Since He Took Office? [Infographic]

How Often Has President Trump Played Golf Since He Took Office? [Infographic]; Down through the years, many U.S. presidents enjoyed playing golf and Dwight D. Eisenhower even went as far as bringing it to the White House lawn ...; Google Alert - site:forbes.com infographic; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2020/11/11/how-often-has-president-trump-played-golf-since-he-took-office-infographic/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjI0NmZkNTNhM2VmNTA0ZGI6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNHrv0w8_wsWnLzv3bIdT3l2sjgsCg; ; November 12, 2020 at 06:00AM

0 notes

Text

Dorset Police 'sorry' for 'racial profiling' Facebook ad

Dorset Police 'sorry' for 'racial profiling' Facebook ad; "Sometimes we use national campaign materials to do this... this social media graphic was one of several used for an historic county lines campaign ...; Google Alert - site:bbc.co.uk/news graphic; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-dorset-54904414&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGmRkMTI2NTgxNzQzNWM2NDM6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNGqPVn0EByqPTU7pOOhpc9JfxVuNg; ; November 12, 2020 at 03:56AM

0 notes

Text

Where Trump's loss fits in the history of US presidential elections

Where Trump's loss fits in the history of US presidential elections; What he and his co-authors have found is surprisingly consistent, as the chart below shows. US presidential election results closely track election-year ...; Google Alert - site:qz.com chart; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://qz.com/1930631/where-trumps-loss-fits-in-the-history-of-us-elections/&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjMxYTJmZGZlMDBhNmUxMGQ6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNFtSH4ayAtOB3tvbC3JNLdbet9yjw; ; November 12, 2020 at 02:35AM

0 notes

Text

Are governments following the science on covid-19?

Are governments following the science on covid-19?; Are governments following the science on covid-19? According to a new survey, many scientists believe they are being ignored. Graphic detail ...; Google Alert - site:economist.com g...; https://www.google.com/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/11/11/are-governments-following-the-science-on-covid-19&ct=ga&cd=CAIyGjliZGE1NGZjOWI1ZjJkNDA6Y29tOmVuOlVT&usg=AFQjCNEpQnm6piHL2iPgaHbYvXRIJyN7JA; ; November 11, 2020 at 04:50PM

0 notes