Text

Old NG Interview I Saved

Hello Nigel, where are you at the moment?

I’m in London, I’m in my studio in Brixton, which is basically a big room with lots of recording equipment and stuff, [Nigel turns his camera round to show us the room] that’s basically it.

How long have you been down there?

I have been here for four years or something. The last few years have been very hard to quantify time-wise, haven’t they? Something like four years.

That room looks familiar, is that where you’ve been doing the new series of From The Basement?

That’s right. I’ve had a few different large studios in London and when I was looking at this place, one of the things that struck me was, ‘oh, it’s just about big enough to film in’, because the main reason that we stopped doing From The Basement all those years ago was that it’s so expensive and we thought about trying to find a permanent location that we could use to bring the cost down and make it more economical and that was one of the contributing things that made me realise that we could probably do it again, because it’s just easier, home turf and a bit more space and time to play with.

What is it when you get that itch to do some more From The Basement sessions rather than, say, make a new record?

It’s like a busman’s holiday really, it’s a completely different thing. It’s not vocational as much, it’s more of an extrapolated hobby, something that I really enjoy doing. It’s more like scratching an itch of being involved in live music. When you’re making a record, you’re really constructing something, it’s like doing Lego, it’s a very fine minutiae in a laboratory, creating something and building it slowly. You start with nothing and you end up with the Notre Dame built in Lego and sometimes you miss just being around people playing live music. That’s what was really fun about doing From The Basement. The original instigation was to try and do an exceptionally good version of a live filming event, but it’s not my job, it’s just something I want to see. So I was like, ‘wouldn’t it be fun to do that?’.

When you’re making records with bands, there’s a moment when you sit down at the beginning and you’re just playing through the material and it’s very exciting when people are in a room and just playing their instruments, if they’re good songs and they know what they’re doing, it’s an amazing feeling and the idea of trying to kind of capture that moment, which is a short period because then you have to translate that into something that bears repeated listening. It’s not as simple as going to a gig.

The From The Basement sessions look great and have a really rich sound, which is where TV music shows usually fall down. No-one should ever judge how good a band are live by watching them on Jools Holland. These things feel more like companions to the records instead of lesser versions.

Yeah, I think what I’ve found is through my obsessive nature, what you should end up with is more like the equivalent of a live EP but filmed. That’s how I see it. I am glad that you say that, I’m glad that you think that because that is the intention really, to make something exceptional, to try and do your best to try and one would hope that it will be a sort of elevated version of that, it’s not wheel them in, wheel them out again, it’s take the time.

One of my very first thoughts about it was when I was doing a Beck record and we had this drummer James Gadson with us, he was Bill Withers’ MD. There’s famous Old Grey Whistle Test footage of Bill Withers playing Ain’t No Sunshine and James is in there. It starts on Bill Withers then it zooms out and there’s this guy with this enormous afro and a gold tooth and a toothpick playing the drums and it’s amazing. I was asking him about that because it’s such an iconic bit of footage, exactly the kind of thing that I felt was missing, and he said that they spent the whole day getting the sound and that really resonated with me because I’ve been in those situations. I mean, Jools Holland is an institution and beyond criticism but there’s a lot of volume there, what we’re doing is something different, it’s more focused on particular things. That was the idea, the priority was making it sound good. I’ve done plenty of TV and radio sessions when you get in and you’re just working against the clock because you have a very small window to get things done. We have the luxury of our own space and I can take my time with the audio afterwards.

How much has the idea evolved given the technological advancements since you started doing it?

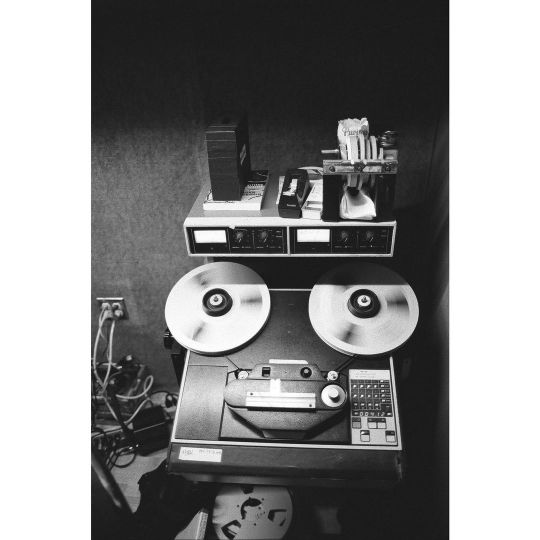

From an audio perspective, not at all because it’s exactly the same equipment I’m using and everything’s the same and it’s the same person doing it. But interestingly, the first time we ever did the original From The Basement in 2005/2006, the reason that we managed to get funding was because we were filming in HD, which was a new technology then. It enabled us to get money from Sky Arts, which was a new HD channel that didn’t have any content and needed content. Of course, what’s happened to television since then is now everything’s 4K. What’s happened is the visual side of it is technologically the state of the art, it’s gone forward. But I would say nothing else. I mean, in terms of recording live music, it’s the same story, we’re still using the same microphones that The Beatles used and that’s something that people talk about when they talk about recording technology versus film and video. Basically, the things that we used to record in the 60s and 70s are too expensive to be made today so we still use old gear because it’s the best quality. All my equipment is 50 years old. It’s quite funny.

Let’s go back to the beginning of your career. What was your first job in music?

I discovered that the only way that I could get into what I wanted to do was to basically to get a job like an apprentice at the bottom. I wrote 100 letters to the 100 24-track studios that were in London in the late 80s and I got a job. My first job was as a tea boy at this place called Audio One that was basically the rebranded Trident Studios, which is in the West End, a very, very famous studios. In the 60s, The Beatles recorded there, Bowie recorded there, Queen were part of the whole thing. It was like a real institution. But basically, I had a pager and I sat on the fourth floor next to the kettle waiting to be beeped, ‘three teas and two coffees in Studio One please’. You were basically finding the opportunities to be able to get in the room and be around the equipment and when people weren’t there, you could go and fiddle around.

Did anyone pull you up on your tea skills?

I was a good teaboy. I make a great cup of tea. I actually worked in a cafe before that so I knew how to make a good cup of tea, very important. Tea making was a very important skill for the up-and-coming record producer back in the day. That’s how Flood got his name. It was the same studio. Two guys started on the same day, they nicknamed one of them Drought and they called him Flood because he was always bringing tea. But they told me when I worked there, “Oh, count yourself lucky, in the old days the assistants had to cook everyone breakfast when they arrived in the morning.” It was that kind of vibe, but it was a really great place to work because it was a very substantial, important place.

Did you feel immediately that you were in your natural habitat?

No, I remember sitting there and thinking, ‘Well, I’m on the first rung of the ladder.’ I was very aware that this was like a temporary situation, the idea was just getting into the right place, basically. I actually was in a band and we went to a studio in Wapping Wall called Elephant Studios, it used to be in Elephant & Castle, that was the first studio I ever went to and it was to do a demo with a band that I was in. That was when I walked into a studio and realised that I wanted to be in this place. It was just this amazing environment, a quiet laboratory of sound. It was very exciting because one of my favourite Pogues records, Rum, Sodomy And The Lash was recorded there so I was asking the guy questions. I was impressed as a 16 year old kid.

How was it going through the Radiohead vaults for the reissues of OK Computer and Kid A Mnesia? Is there anything you were surprised about?

They’re very different animals. OK Computer was more of a regular process in as much as we had some songs and we went into various places and tried to record them and did it different ways and ended up with the best possible outcome, whereas Kid A was taking everything that you’ve gained and worked for and throwing it in the air and looking at the pieces and going, ‘Okay, well, this is what we’re trying to do’ and starting again. And, obviously, I worked on the Kid A stuff more recently and there’s a lot more of it, and there’s a lot more stuff that went by the wayside that was for good reason.

It’s funny when you go back and look at stuff, especially when you’re looking at it from the perspective of looking for things that haven’t been released or extra material that might be interesting, everything is for a reason, you left it off for a reason, you go back and what I was surprised by was that all of the decisions that I made were absolutely right. And also my memories of things, I can remember recording Everything In Its Right Place and it was just me and Thom in a room trying to do something that was not what we’d done before and I remember him singing the vocal once, singing it a second time, looking in his notebook, saying, “ah, ‘yesterday I woke up sucking a lemon’, I can’t say that,” and me saying "yes, you can, you’ve got to say that, let’s do that!" and doing that take and it being like this magical thing, then going back to the tape and looking at what’s on the tape and there it is, the first take it’s got no lyrics, the second take it’s a repetition of “the two colours in my head” thing and then the third take it’s “yesterday I woke up sucking a lemon”. That’s exactly how I remembered it. And even though it’s more than 20 years ago, I can remember that process and it’s there written down in a physical form for me to see.

When you reach 51, you start questioning things that you remember and how you remember them and ‘was it really like that?’ and ‘did I actually do that?’, so to go back and look at something and it be plain as day how you remembered it was like, ‘oh, that’s fascinating.’ The other thing that was really funny about going through Kid A was the fact that we hadn’t really got the concept of file management together yet. I had to look on a video that I had of us recording to find the box that was the hard drive, which had everything on it that was not on tape, because we were working on tape and we were also working on a computer. It was like, ‘what are we looking for again? I’ve forgotten.’ It’s a SCSI drive that looked this particular way, something that is completely obsolete now. They found it on a shelf, dusty at the back, nobody knows what it is and then not being able to open all the stuff on it was pretty funny. There’s some bits we can’t find.

They’re in a room somewhere, like at the end of Raiders Of The Lost Ark.

Yes, exactly. There is one of those, a kind of Radiohead equivalent of that.

How different is the relationship with you and Thom from project to project, does it change if you’re doing Radiohead to Tomorrow’s Modern Boxes or to a solo project like Anima?

Well, obviously, it’s really different. I mean, the whole kind of instigation of us like doing The Eraser was off the back of that I was not going to work with the band again because we thought I needed a break, we’d gone through Hail To The Thief and it was like, ‘foof, everyone’s tired.’ and they went off to start working on songs for the next record. I was like, ‘okay, it’s fine.’ Thom was like, ‘Maybe we’re gonna work on our own, we’re gonna work it out,’ and I was totally cool with that, and then I basically got a call two days later saying that he wanted to do this solo thing and so we started working together.

What we found was, interestingly, when we were in a room when it’s with Radiohead, I was always butting heads with him because it was basically me and the band, I’m trying to manage a relationship between him and the band and it’s me butting heads with him and trying to work on behalf of the band. As soon as he and I were alone, we found that the dynamic was completely different, we were pulling in the same direction and it was incredibly productive. So it worked really well and we did that record and then actually I ended up doing In Rainbows anyway.

You know, relationships change. It’s nearly 30 years now we’ve been working together so things do change and the way that you work changes. But I think that what’s evident is that you only really have formative relationships like that once. So Thom will never find another me and I’ll never find another Thom because we’ve just worked for so long together. And that goes as well for the other guys in the band but in a different way, because obviously Thom and I have gone off, I’ve done something like 14 albums with Thom, whereas I’ve only done nine or something with the rest of them. There’s so many different permutations of how it works but the fundamental bottom line is it works. We just have this ability to just be very productive together and that’s a really precious and important thing and it changes in within the context of whatever we’re doing. It doesn’t really matter, so then we go and do Atoms For Peace and it works in a different way but it’s still fundamentally the same relationship. It’s crazy. It’s a long-standing thing.

Which record that you’ve been involved with do you think is the most overlooked?

Here We Go Magic’s A Different Ship. It’s a band I really loved and it’s one of those stories of finding something you really love and working trying to help them and then them imploding pretty soon after the record was finished so the whole thing just ground to a halt as it was in that format, a couple of people left. It’s a shame because I think they were a really great band in that format and they could have moved forward and carried on being great band. I feel like that’s a little gem.

What’s been the hardest period of your career?

I definitely had a beam me up moment when we were doing that Band Aid 20 single!

Haha, go on…

Well, it was just one of those things where you feel like, ‘if I can contribute something then I can help and it’s such a good cause I should do it’ and getting musicians together to do something like that is quite difficult. I was working with McCartney at the time so I managed to strong arm him into coming in and playing bass. And obviously Geldof’s hassling Thom so I had this sort of funny superstar band, which is Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood and Danny Goffey on drums and Paul McCartney on bass and Fran Healy doing the frontman-y bit to get the backing track. It just was a bit of a clusterfuck trying to get the actual track together. The whole thing is just so not me and then what happened was we just couldn’t really get a good take so I was up until three in the morning trying to like cut it together without much help from certain parties. It was like, ‘What’s going on here?!’.

Tell me about the making of The Smile record. Out of all the Radiohead and Radiohead-affiliated records, that’s the one to me that has the most mystique, it seemed to come out of nowhere that Thom and Jonny had started a new band.

I think there’s a little bit of cards to the chest about the whole thing. I think it just came out of Jonny writing all these riffs, waiting for something to happen. I think he was writing music and it’s been such a weird time the last few years, Ed’s gone off and done his solo record so that’s kind of been out of the picture and then Covid hit, I think there was a desire to make music so him and Thom were getting together writing stuff. It’s just a quite organic process, it was over a long amount of time, over a couple of years. It started here in this studio and then I went off and did the Arcade Fire thing so that slowed everything down a little bit. And then when once that was done, I came back and finished it off. But it’s the same thing, it’s the same kind of ingredient, those people that I’ve worked with all this time so we’re kind of just doing what we do and we have our ways of getting things done.

With that in mind, how was it walking into Arcade Fire to produce We, working with a big band you hadn’t collaborated with before?

The thing with those guys is it’s a completely different animal. They’re very much the ultimate home studio recording artists in a way, they’ve always done stuff on their own and I think it was quite different for them to have a producer-producer. In some ways, it worked really well, in some ways it maybe made it a little harder, because I have my feelings about things and integrating that into the whole thing can be complicated. But I think, at the end of the day, we worked well and there’s a lot of material that actually isn’t on the record that is really good. But I think that they made a good decision by keeping that record short and sweet, so we’ll see what happens. I’ve known those guys for years. It’s a classic thing where you meet people around and about and then always in the back of your mind, you’re like, ‘Oh, this is a possibility.’ It was kind of miraculous that it happened, really, because of Covid what we did is we went to the middle of nowhere, outside El Paso, Texas, and basically lived in a cult for a couple of months. Nobody came in and nobody came out, people delivered the shopping, that sort of vibe just so we could be able to do it. It was a method to make it possible.

That sounds intense.

It was intense, yeah. Making music is intense sometimes, especially when you’re dealing with other human beings because there’s so much that goes on in the soup of making music, that’s why it’s wonderful.

Do you think there will be another Radiohead album?

I don’t know. Obviously, I can’t answer that!

This piece is coming out to coincide with Warpaint’s From The Basement session, how was that?

Oh, well that I love because, again, it’s a band I’ve never recorded but I know them all really well, they’re friends and have been friends for a long time for many years. It’s serendipity that it becomes a version of a way of working together that is really pleasing for all of us, just a day in the studio, and we get to record, capture this thing live and I get to fulfill my little fantasy of doing something with them.

0 notes

Text

Nigel on IDLEs

Godrich has reached a point in his career where he can be selective about his projects. “I rarely, these days, have any sort of desire to work with anyone, to be honest,” he tells me, a few weeks after my conversation with Talbot and Bowen. “But they’re doing it for the right reasons and the right intentions – and they’re really fucking sweet people, which, believe it or not, is a very important thing to me.” He wasn’t, and still isn’t, closely familiar with the lineage of their sound, but after relaunching his beloved live-in-studio music series From The Basement with their performance, he glimpsed the potential for something within them that had, until then, been untapped.

“I always think about things selfishly, like, ‘What would I like to hear?’, Godrich explains. “I see this band, I see them perform, and I see Joe who’s a star. And I started to think, ‘I wish they would…’, in that kind of imaginary way. I thought it would be interesting to see how they would translate if he was a little bit more musical, if he sang more. Has this tone which is really quite amazing. I was talking to Mark and Kenny, and we all agreed it would be a great angle to take - and Joe was on board. The reason I was drawn to do it was because I could see a role I could play; I could see a possible outcome.”

It was the first time Godrich had worked on a record where not a single word had been written beforehand. It’s how IDLES have always worked: Bowen and the band conjure the sound, dictate its mood and climate, and then Talbot communicates that sound through melody, like beams of light refracting through a prism. Godrich was both astounded and disarmed, he recalls, at the instinctive way in which he would write a song at the microphone, in that very moment. But rising to this new musical approach, at first, didn’t not come easily to Talbot.

“First of all, Joe is the one at the front there who’s having to sing all this stuff,” Godrich points out. “He’s put in a very vulnerable position and he’s the one who has to make it work. I know, for him, that was difficult because I think he puts himself forward with a very aggressive kind of sensitivity on the previous records. In order to kill the toxic masculinity of something, you have to have that masculinity there in order to detoxify it – that’s part of the magic of it all. So then, suddenly, to work without that edge, I felt that he was a bit nervous about it. And rightly so. He’s a sensitive guy, and that’s what makes him such an extraordinary performer.”

At the end of our conversation, Godrich also confesses, “I didn’t really want to do any interviews about this. It’s nice to retain an air of mystery sometimes, but these boys deserve everything that I hope is going to come to them.”

--------------------------------------

Think that's a subtly revealing interview, actually.

I know Nigel has expressed that most music isn't very good right now. But the air of mystery quote at the end is another clear reason he doesn't interview much or talk details.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

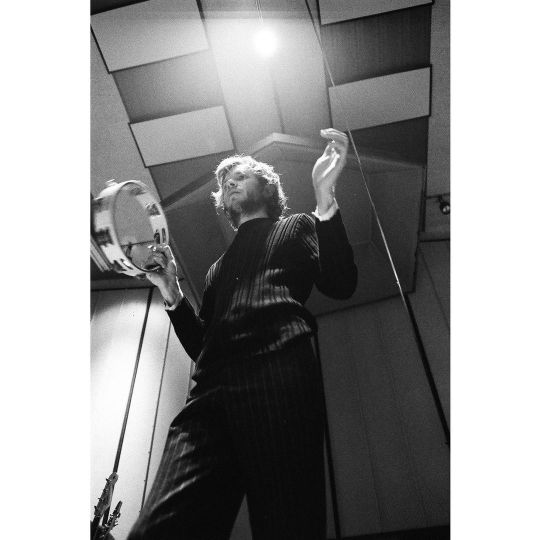

The new Idles record, TANGK, is out.

Some shots of Idles at Nigel's studio. You can see the Soyuz SU-017 with "Room" labeled on its side, the M49 as an overhead (just like the Ultraista session), 57 on the snare, Coles as L/R overheards, RE-20 on kick, C12As on the toms, U47 and 414 in the room (could just be around or for vocals), most likely a U67 on one of the amps. Nothing you haven't seen before from Nigel and From the Basement.

The Studer is on and presumably recording.

Note that the Coles overheads are raised relative to the cymbals and the cymbal height and angle (thus, the overheads are not necessarily even with each other).

The Moog modular, Prophet 5, plenty of guitars and some other things that I'll identify later.

In the video, you can see the Tannoy Gold monitors on top of the API 2488, a little bit of the 1081s, BX-10. You can hear Nigel say, "I can tune this as well," in case you were ever wondering if he tunes stuff (every engineer ends up tuning stuff...).

It's cool to see the whole open expanse of the space. There's not much obvious acoustical treatment, just curtains.

1 note

·

View note

Text

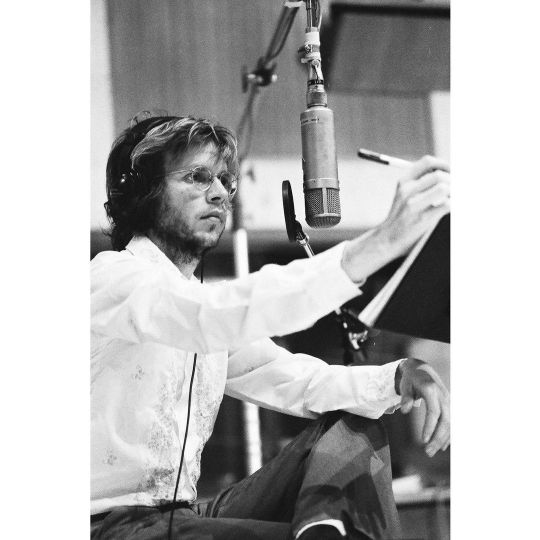

A few pictures from the Mutations sessions from Beck's Instagram.

Nothing super new: Ocean Way Studio B, 47 and C12 on vocals, Ampex ATR-102 as the mixdown medium, C24 as a stereo overhead over Joey's small kit (no tom mics, only looks like a snare mic and probably kick) and a picture of Justin Meldal-Johnsen with a Neve 33609 (and, though grainy, what might be a Sansamp PSA 1).

All most likely recorded through the Dalcon console.

EDIT: Thanks to a kind user who pointed out that it's a C24, not C12 over Joey's kit.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Allen Sides on the Dalcon console

youtube

A few quotes from the Sunset Sound podcast with former Ocean Way owner, Allen Sides, who sold the Dalcon console to Nigel:

On the Dalcon console, we had 40 API 550As normalled to every input as well as the EQ that's in the console. So you had six bands for every channel.

[on the EQs] It was based on that [Spectrasonics] but they were custom made. But they certainly had some attack.

Joe Chiccarrelli

They had a sound but they were very open, very sweet, very hi-fi. Then you had the APIs that were more aggressive so you could mix and match on every channel. And then the preamps on that too were very open. Not a lot of gain. Something about that console was extraordinary.

The thing that's great about that console is, from microphone in to buss out, you went through three amps for the entire console. And the EQ was in the feedback loop of the line amp. If you put the EQ in or not, there was no electronics. It was passive so individual coils for each frequency. Then even the 550As were totally bypassed unless you pushed the button in. The console ran on +/- 22V rails. It will deliver +25 out without a transformer. Full outs. So the output - we had 1:1 transformers, plus a direct out. So you could have balanced or unbalanced but you didn't have to go through any transformers unless you wanted to. The amplifiers in that console slew to 200V a microsecond. So Massenburg called it the fastest console on planet earth and CLA called it the baseball bat console because it was so goddamn punchy.

I had this fight between Beck, Jon Brion and Nigel, but I had promised it to Nigel first. He's a lovely guy.

[Bill Putnam] built one portable one which was 24 inputs with a sidecar. He ended up installing it in one of the rooms and all the engineers liked it, they thought it sounded great. So he said, "Great, let's build three of these." And there are gonna be three custom consoles. So he built the first one and into the production, there were some issues. If you looked at this console sideways, it went into oscillation and all the meters would pin.

I bought it from Bill and I took it to my garage and Jake Hoffman and I spent two months stabilizing it. Because it had bandwidth out to half a mghz. So we settled on 100k bandwidth. And we figured out how to reground everything and then moved that console from the garage to [Ocean Way] Studio B.

Beck has the Green custom console. He bought that custom console from Dennis Dragon.

When I did sell that to Nigel, Beck got really mad at me and so did Jon Brion. To be honest, I could've probably gotten 100k more for it, I said I made a promise. And Nigel was a lovely guy. I made an obligation and that's what it is. I have to let him have the console. I made Beck a custom 4-channel mic pre that matched the console for him. It's a one-off for him as a favor. He has that.

0 notes

Text

Ultraista String Recording Photo from the Venice Biennale

Nigel mentioned that Ultraista had a chance to record strings for the second record during the Venice Biennale (when Nigel lent his rig to Xavier Vielhan's installation). This is a photo from that day showing the setup.

Should be noted that the violin/viola mics are all facing the players with their capsules perpendicular to the ground, parallel to each other, no angles/tilt. With an X-Y or maybe ORTF pair in front of the whole ensemble and maybe a wider spaced pair of Coles (can't see the second one). Likely similar to other setups we've seen from In Rainbows and A Moon Shaped Pool.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Paul McCartney on Chaos and Creation in the Backyard and working with Nigel

“Nigel had a clear idea of the record he wanted to make,“ explains McCartney, “and he started off by saying, ‘I want to make a record that’s you.’ We worked a week with my live band, but Nigel decided to take the approach of me playing most of the parts. ‘I’d like to hear you play drums,’ he’d say. So I talked to my band about it, and they said it was no problem if they didn’t play on the album. They were into whatever it took to make a good record, and they said they’d be happy to play the tracks live.

Going into pre-production for the album, was it a surprise that Nigel wanted to pursue a very simple and natural approach – one that almost brought you back to the unfussy charm of your first solo album?

“It really did sneak up on me, but I figured that we were looking for some sort of direction, and it was good to get Nigel to make some of the key decisions. He definitely wanted to present the whole thing straight from the shoulder, and just document some good songs, some good singing, and some good playing.

“Once I caught onto his plan, I realized that it was good. We’d done this sort of thing in the Beatles. It was either Revolver or Rubber Soul – I can’t remember which – where we outlawed echo to keep everything dry and really in your face. It just presented everything right there with no added cosmetics.

“For my part, my main contributions were the songs. I would bring in a tune, and if he didn’t like it, he’d just say, 'I’d rather not work on that one. What else have you got?' He was pretty tough, and at first I thought, 'Dear me, I’m not going to like this guy.' But, in actual fact, I respected his decisions – although there were a couple of songs that I fought for."

For example?

“'Riding to Vanity Fair' is the main example. He wasn’t too keen on the first version of that song, but I could see something in there. I said, 'I’m not sure you’re right about this one, Nigel.' I didn’t quite understand what he didn’t like, so I said, 'Look, we’re going to make this work.' But up until a few weeks before we completed the album, the song still hadn’t made it. Eventually, I sat him down and asked, 'Tell me exactly what you don’t like about this.'

“We went through it line by line, and we ended up completely rewriting the melody. It used to be much brighter, but Nigel thought it was too chirpy. So we took it to a different place by inserting a more moody melody in the second and third lines. That changed the nature of the song – I mean, we pretty much rewrote it – and it finally made the album.“

How did you approach the “Paul plays it all” tracks?

“It might be piano, guitar, bass, drums – that kind of order. But it varied every time, really. It came down to whatever we fancied, and if Nigel thought something was missing, we’d add a part later on. Some of the songs are very sparse on the drums, for example, and Nigel would sometimes add percussion to fill out parts. On 'How Kind of You' and 'Friends to Go' most of the song is just a bass drum. We didn’t bring in the whole kit until near the end of the song.“

That reminds me of when you played drums on the Wings album, Band on the Run. You also didn’t use the entire kit for some of those songs – which kind of weirded me out at the time – but those tunes still rocked.

“I’ve always thought it was an interesting approach to go for something unconventional regarding drums and rhythm tracks. In the ’60s, when the Beatles were quite experimental, we’d say to Ringo, 'Aw, man, didn’t you use that snare drum on the last track? Let’s not use it. Let’s get out a packing case, or hit the back of a chair or something.' But then things got sort of boring – a bit more straightforward – in the middle of the ’70s.

“People would get a proper drum kit, and play traditional drums throughout a song, and you just had to be clever with the musical arrangements. I told Nigel, 'We’d also do things like playing tambourine on a chorus, stopping it for the verse in favor of handclaps or something, and then bringing in the tambourine again on the next chorus.' That way, you got the feeling of light and shade, and we did a lot of that on this record.

“The more you listen to it, the more you’ll hear how things have been placed very carefully, yet they achieve the effect that we haven’t even thought about them. We tried to make it seem effortless. There are quite a few nice little layers on the record – colors that Nigel thought would fit sonically within a song without calling attention to themselves. As a result, I think the album sounds very earthy.“

How did you develop your guitar parts for the album?

“'Organic' was a word that came up quite a bit as we were working. I would normally track a song using the instrument I wrote it on. For example, 'Friends to Go' was written on my Martin, so I started there, and just sang the song.“

There are also some very beautiful and subtle electric guitar layers on that song.

“Well, what happened was that we fell in love all over again with my Epiphone Casino, which I played on a lot of Beatles records – the 'Paperback Writer' riff, the solo on 'Taxman,' and so on. It also feeds back nicely. Nigel always kept going back to it, saying, 'That is my favorite guitar in the world!'

“I’d just get a little variation in the color by using either the treble or bass pickup, and then I’d stick it into my Vox AC30 – so it’s really the old Beatles sound. Thank goodness for my Epiphone Casino. Where would I be on this record without it?

“Occasionally, I’d pull out my goldtop Les Paul to do something a little bit more thrashing, and Nigel would say, 'Uh, it’s a bit heavy rock.' I’d say, 'Yeah, I think that will work.' Well, he’d have none of that. I mean, it got to be a bit of a joke, because every time I’d pull out the heavy rock, he’d say 'no.'

“It got to the point where I started to feel like some teenager trying to thrash in my bedroom, and daddy not letting me do it. But Nigel was right. The guitar sounds we recorded have a continuity that makes the album sound sort of holistic. You don’t feel like you’re going out of one room and into another. You just feel like you’re at Paul’s house.“

Given your ability to write in so many different genres, how do you discipline yourself to put a specific project in one stylistic place?

“I really do credit Nigel with doing that because, in a way, that’s a producer’s job. He has to take a look at what I’m doing and get enough variety, but, at the same time, to make a good album, everything must sound like it all came from the same hand so you feel like it’s not a patchwork quilt. There has to be something that pulls it all together, and I think that something is Nigel’s sound.“

Could you provide an example of how Nigel would encourage you to redirect a song that didn’t fit his view of the album’s vibe?

“'How Kind of You' was originally a jangly acoustic thing [sings the harmony], and Nigel said, 'Well, we can make it that way, and it will sound nice, but what if we tried a different production idea? What would you do if we didn’t use the acoustic?' We had a lot of organic, earthy instruments in the studio – including a really great pump organ. So I started pumping away on that, and it created an ocean of sound, rather than a deliberate rhythm.

“Then, we added some piano loops, and it produced this feeling of the ocean kind of rippling with the sun dappling on it first thing in the morning. When I sang the song over that, it was slightly unearthly. Now, when we eventually brought in the guitar, it really made a difference. Instead of it being there from the beginning until the end, it’s like 'Oh! Here’s the guitar.'“

On that note, the solo on “Promise to You Girl” really jumps out of the mix. I don’t think many people would be so brave as to mix something that rude and dry so far up in the mix.

“You know, if Nigel likes something, he mixes it right forward. That takes nerve, but that’s Nigel’s nerve. The guitar I used for that solo was the Casino. I kept trying to use other guitars, but Nigel would say, 'You know what we should try, don’t you?' And I’d say, 'Casino?' 'Yep!' [Laughs]

“The other funny thing about mixing things so dry happened on 'Jenny Wren.' I had heard this low, mournful flute during Ravi Shankar’s bit at the [2002] Concert for George [Harrison]. The instrument turned out to be a duduk, and we decided we had to have that sound on 'Jenny Wren.' So this Venezuelan duduk player, Pedro Eustache, comes to the studio, asks for some reverb in the headphones, and does a great take.

“During the playback, Nigel had the duduk absolutely flat and dry, and Pedro asked for some reverb. We said, 'No, Pedro – it’s beautiful as it is.' And that freaked him out! He said, 'No! You’ve got to have some reverb. That’s the loudest duduk I’ve ever heard!'“

On “Jenny Wren,” you employ a very individual fingerpicking style that pushes and pulls against your voice. What informed that approach?

“I should make up some great, glamorous story about that particular style, but it wouldn’t be true. The thing is, in our youth, the funky guys could fingerpick using all their fingers, and really do it right. John [Lennon] did that on 'Julia,' and he tried to show me how to fingerpick conventionally, but I could never quite do it.

“Still, I wanted to write something in that style, so I originally wrote 'Blackbird' using simultaneous melody and bass lines. But here’s the thing: I just kind of strum with my index finger whilst I’m sort of holding down the other two notes. That’s what gets that particular sound, and it’s just something that developed because I couldn’t do a proper fingerpicking thing.

“I wanted to revisit that style, so I used a similar approach on 'Jenny Wren.' Of course, on tour, I’d wear down the fingernail on my index finger until it drew blood. It was my wife, Heather, who suggested that I put on an acrylic nail. 'That’s what girls do,' she said. Well, that nail is a lifesaver.“

“The other thing about 'Jenny Wren' is that I’m playing my Epiphone Texan – the guitar I played 'Yesterday' on – which is permanently tuned down a tone. So I’m playing 'Jenny Wren' in C, which is more conducive for my guitar playing, but, with the tuning, the song is actually in Bb. It was the same with 'Yesterday.' I was playing in G, but the song was in F, which was a better key for my voice to sing that song in.“

The instrumental bonus track is a surprise. It sounds rough and ready – and it totally rocks – but it’s also very musical.

“Well, we were just looking at the puzzle of how to start an album, and we considered doing some sort of jam/noise thing for about a minute, and then go into the first song. That kind of thing takes the pressure off the first song.

“So Nigel asked me if I could just go in and make something up. I agreed to the challenge, and I got on the piano and tried to thrash something out that might be an opener. As I was going out to the studio, he said, 'Seeing as how you’re going to make up one thing, why don’t you make two pieces?' To which I thought, 'Well, maybe I’ll do three!'

“I very quickly got a little piano riff going for the first bit, then I got on the drums and bashed out a drum thing, and stuck a guitar on it. I was hopping from one instrument to the other without giving myself too much time to think. I would chug along on something, and Nigel was like a kid at Christmas. He’d say, 'Okay, can we have a high riff now?' I’d say, 'Sure! One high riff coming up.' And I’d just throw something on it.

“We had the feeling that if it didn’t work, it didn’t work. There was no pressure. It felt like the grownups had left the studio to us, and we were just like kids who got to do anything we wanted to. When we had done all the takes, we mixed them all up. The whole process took about three hours.

“However, when we tried the piece at the beginning of the album, we decided it didn’t really work. Instead, we made it a so-called 'hidden' track at the end of the album. Although, in this case, I think we should have called it a 'not-very-well hidden track, because it doesn’t wait more than 12 seconds before it comes in.“

The guitars are pretty ballsy on the hidden track. Did you finally get to pull out the Les Paul for that one?

“He still didn’t let me use it, man! Les is not going to be pleased! But I blame Nigel."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture of Thom listening in front of the console. Looks like it may be a Trident A/B Range, but I'm not entirely sure. Those desks are famed for their immediacy and punch (and sensitivity to RF!), not unlike the Dalcon. Plenty of both UK and US classics were recorded on them.

I'm also not sure if this is the other Nigel control room at his place, the one we haven't seen, or another studio entirely. The gear in the back is a lot of standard stuff we've seen from Nigel/Thom/Radiohead before, plus some other things from a lot of the same companies from Nigel's now well-known In Rainbows / Venice Biennale / From the Basement II rig:

SSL G-Comp, Focusrite Two-Dual preamps, Focusrite ISA-430 MKII, Ampex 351 preamps, Pultec EQP-1A3, Pultec EQP1A (2), rackmount Sansamp, GML 8200, Summit EQF-100, Summit EQP-200B, UREI LA-4 (2), Neve 83085 modules (2), Empirical Labs Distressors (2), Manley ELOP, Retro 176, UREI 1176s, DBX 165 w/o the Peak Stop knob or a DBX 162, two DBX 165As, Teletronix LA-2A (2). Pro Tools HDX rig to the left.

I will look into some of the stuff I missed and is thus far hard to see.

A lot of stuff. If I had to make an educated guess, I'd say this is Nigel's place. That's mostly based on the presence of the Sansamp, Focusrite and Summit stuff - just seems like a particular signature of whatever taste in gear he might have.

And he's likely one of the few who can afford a Trident A/B-Range and also understand its historical significance and sonic qualities. Again - this is conjecture and unconfirmed!

(Also, note to The King of Gear guy: before you steal this information as your own, please give some credit to the source.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture of The Smile during their Abbey Road sessions.

Though Sam Petts-Davies produced and engineered, pretty classic Nigel-isms from what can be seen. Coles 4038 on L/R drum overheads, what looks like a Neumann 67 on Johnny's amp, a FET 47 on the Ampeg B15. The drums are treated in the classic, dead 70s style - no front head on the kick, towel taped to part of the snare drum head and guessing Tom Skinner played quite quietly at many points on the session. A pair of Coles 4038s in Blumlein, guessing for some room sounds. The Rhodes is mic'ed up but the mic is obscured, as is Thom's amp.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I actually love…it’s hard for me because I’m a record producer, I’m supposedly supposed to see things in people’s demos and extrapolate them. But I usually prefer people’s demos because they have so much more soul in them. You get a sense of intimacy and honesty and all that kind of stuff." - Nigel

In case, you never caught this mix on NTS Radio from Nigel, here it is. The above quote comes in a reference to the Prince demo on the setlist, in addition to a Lou Reed demo he mentioned.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Via Twitter and Instagram, The Smile have posted a few photos from recording sessions for their new record (some of which they have played live). A drum kit miced up with what looks like a CMV 563 (in what looks like the heart/crotch mic position), among other indecipherable mics and various toms. An Otari MTR-90 with unfurling tape. Photos on top of the API 2488. And lastly, a session at Abbey Road with two heavily gobo’d booths (for deader sounds), a Rhodes, upright piano, a pedalboard, etc. among many other indecipherable things. Nothing that hasn’t been covered here before. Hopefully more stuff to come.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Interview with Mikko, touching on a lot of relevant topics from Nigel to recording philosophy.

“He said, ‘Stop worrying about making things sound good, worry about making them sound interesting.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

New Nigel podcast with Jamie Lidell!

Haven’t listened yet, but enjoy.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New Cue Interview with Nigel

https://thenewcue.substack.com/p/the-new-cue-191-july-27-lost-in-music

Nigel was interviewed by The New Cue (Substack). You’ll have to subscribe but it’s a terrific interview, one of his best, covering studio sessions, From the Basement, Nigel’s beginnings as a tea boy and other topics.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

The Smile 1

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video from The Smile sessions and Nigel’s studio

https://twitter.com/nigelgod/status/1525183693941252098

https://twitter.com/nigelgod/status/1525184952454860801

https://twitter.com/nigelgod/status/1525192849897185286

https://twitter.com/nigelgod/status/1525194267123240960/video/1

On Twitter, Nigel posted some cool footage from sessions for The Smile’s new record. You can see Johnny, Thom and Tom (Skinner) playing together, Thom doing some delay dubs on the API desk while Nigel seems to be operating the multi-track from a Mac (interesting to see him work digitally vs. off tape). It should be noted that in addition to the known rack with Rev. H 1176s / Tubetech CL1B and E.A.R. 660, you can also see Tannoy speakers similar to the ones at Jonathon Wilson’s 5 Star Studios in Los Angeles.

Nigel’s setup for Thom’s piano on “Pana-Vision” looks like a pair of AKG C12s aimed at the hammers. Unclear if both mics are used but the track is stereo on the record. Just conjecture, but he might be taking advantage of the polar patterns to get both the piano and vocals at the same time in figure 8.

On Tom’s drumset, all you can see are a 4038 and an M49 as overheads. All very low to the kit. You can also see a lot of blankets creeping around the gobo, suggesting the kick is heavily covered for separation. A mono SU-017 seems to be a room mic in two of the videos.

You can also see some known bits of Nigel’s synth collection: Moog modular, Prophet 5, etc.

Notable seeing Nigel’s setup for horns. Nothing about the placement of any of the mics is too esoteric - mic’ing the bell of the horns and the bridge of the upright:

-stereo pair of SU-017 tube mics

-stereo pair of AKG 414s (can’t tell if they’re EB or B-ULS - they look a little too big to be the tube AKG C12As)

-U47s on trumpet, trombone and tuba

-Judging by the stand connector, a U47 FET on upright bass

-U67s (or possibly U87s) on sax and flute

-I can’t see what’s on oboe

-Roland CR-78 and AKG BX-10, on top of the previously known Neve 1081 rack. The BX-10 is a classic reverb - technically a spring but does not sound like one (no typically springy “boing” sound).

In general, a cool open cozy spot with gobos and everyone playing in the same space.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Joey Waronker Interview

https://www.listennotes.com/podcasts/drum-candy/joey-waronker-roger-waters-HhlDrMZO_EG/

Joey did a nice drum-centric interview with the podcast Drum Candy. He mentions using an unusual Ludwig Nesting Kit from the 70s (S-340?) when tracking with a few people, including Nigel.

When asked about playing with Thom, he mentions using smaller kits and also playing along with sequenced drums (”tracks”) instead of replacing them during recording:

“For sure, if we’re doing stuff, there’s definitely a discussion. Like, a jazz drum kit - let’s see what happens. But my go to is definitely like how do I interpret…how can I reinvent the wheel on this and show up with…I’ve developed a whole kit around [Thom Yorke’s sound]. What will sound like live drums but a drum machine if I’m just playing for a live show? And this is going to be cool because then it’ll be a palette for recording. That ends up being like tiny snare drums, etc. etc. I’m way down the rabbit hole on that stuff. I have a whole kit that’s set up that’s like a tiny…A children’s 16” bass drum and tiny snares and teeny tiny hi hats from Istanbul and noisemakers. A lot of people do stuff like that but I’m definitely into the idea of how do you make a drum set that doesn’t sound stock. And if you’re gonna be stock, that’s great, that’s fun but so many of the collaborations I’ve done over the years, there’s the mentality of everyone’s trying to do something new…And with Thom, he’s super deep into [the electronic programming]. It’s better for me to be ‘acoustic drum guy.’ What’s gonna work with Ultraista is somewhat of a similar idea but it’s more like, ‘We can use a small regular drum set and intermingle that with programming.’ But the last time we were doing stuff, I was like, ‘Let’s use the [electronic] bass drum on the tracks.’ It gives it this quality where it’s like, we’re trying to make it electronic hybrid. We’re committing to using tracks anyway. So the sound is amazing. It’s so solid and that way. The obsession over different bass drum sounds is completely achieved. Because each song has a separate bass drum sound…[The electronic drums] were on playback and I wanted to play off of them. I’ve tried all kinds of things. We (Ultraista) were doing stuff where we were doing that music which is pretty experimental and electronic and we committed to not using tracks [live]. It was a lot of work, it was super cool because we were doing it but you’d have to be a nerd and be like, excited, because at a show, you just hear the music and if you look at the stage, it’s mostly me looking like I was knitting, triggering pads, and trying to keep triggering loops. And Nigel’s like playing bass and keyboards and looping things and doing a vocal thing and Laura the same. To us, it’s like whoa that’s pretty magical…You’re a good musician, you think that’s what you have to do, but you try it and learn it’s not as important as you think it is. And it’s like, good, if we can play with the tracks, that means I can, like, PLAY. And perform [laughs]. I can still play the bass drum too but I’m not holding down the fort. I’m excited to push the limit of what you can do creatively with tracks like that.”

0 notes