Text

Love of My Life, een ludomusicologisch wonder

Op vrijdag 15 mei 2020 werd het Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert uit 1992 live op YouTube gestreamd. Queen besloot dit te doen om geld in te zamelen voor de WHO die zich op het moment bezighoudt met de coronacrisis. Door dit evenement ben ik andere concertregistraties van Queen op YouTube gaan kijken. Wat mij opviel was dat bij elk concert enorm veel interactie was tussen Freddie Mercury en het publiek. Hij speelde met het publiek een soort vraag-en-antwoord spel die elke keer voor een andere uitkomst zorgde. Dit deed mij denken aan ludomusicologie. Deze term wordt door Kamp, Summers en Sweeny als volgt gedefinieerd: ‘Ludomusicology, at its broadest, attempts to see our engagement with music, any kind of music, in terms of play.’[1] Simpel gezegd, de verwevenheid tussen spel en muziek of visa versa. Je zou deze concertregistratie dus als een ludomusicologisch object kunnen beschouwen. In deze blogpost neem ik jullie mee langs een paar interessante ludomusicologische theorieën en zal ik deze uitleggen aan de hand van de concertregistratie van het nummer Love of my life van Queen in het Wembley Stadium in 1986.

Allereest zal ik een beeld scheppen van de video (de concertregistratie). De video begint met beelden van de gitarist van Queen, Brian May. Er wordt ingezoomd op zijn handen die de intro spelen van het nummer. Je hoort het publiek op de achtergrond en later zie je Freddie Mercury, de zanger, die inzet. Na de eerste zin seint hij naar het publiek dat zij kunnen zingen. Wat opvalt is dat de zanger het publiek dirigeert. Met armbewegingen omhoog en omlaag geeft hij aan wat de melodie is van het nummer. Met abrupte bewegingen geeft hij inzetten aan. Het publiek zingt de tekst en melodie van het nummer zelfstandig. Hij geeft zelfs aan wanneer ze klaar zijn, door een lange beweging met zijn arm een kushandje en een buiging, waarna het publiek begint te juichen en klappen. Er volgt een vrij kort instrumentaal tussenstuk. Het beeld gaat kort naar de gitarist, maar iets voordat de zanger weer inzet zie je het publiek en de zanger weer op beeld. De focus ligt op hem tijdens dit optreden, dit valt op door de manier waarop er met beeld wordt gespeeld.

Wanneer de tekst ‘I still love you’ begint, laat de zanger opnieuw het publiek meezingen. Dit signaal gaat zo snel dat het publiek heel gefocust moet zijn om meteen te kunnen reageren. Even later zegt hij in de microfoon ‘I still love you’ en wijst naar het publiek. Hij maakt het op die manier bijzonder en persoonlijk. Freddie Mercury en Queen in het algemeen zijn erg gefocust op publiek en interactie binnen een concert. Het publiek begint te juichen en te klappen en de zanger loopt weg. Er volgt een gitaarsolo terwijl het publiek mee neuriet met de melodie. Dit geeft aan dat iedereen de melodie kent. Ook het beeld is gedurende de solo gefocust op de gitarist. De zanger zet in en het beeld focust zich weer vooral op hem. Freddie Mercury laat nogmaals het publiek mee zingen en daarmee is het nummer afgelopen. Er klinkt gejuich terwijl de zanger buigt en grappige bewegingen maakt. De video eindigt met beeld van het publiek in het stadion.

Naar mijn interpretatie bevindt het spelelement zich in de interactie tussen publiek en performer(s). We kunnen deze concertregistratie verbinden aan de verschillende onderdelen van Johan Huizinga’s klassieke definitie van spel:

‘Naar den vorm beschouwd kan men dus, samenvattende, het spel noemen een vrije handeling, die als “niet gemeend” en buiten het gewone leven staande bewust is’

Het concert is gescheiden van het dagelijks leven zowel fysiek; het stadion is een afgesloten plek, als sociaal; het creëert een bepaalde gemeenschap door de afscheiding van het normale leven. De spelers, het publiek en de performers, voelen zich verbonden met elkaar omdat ze zicht buiten de maatschappij plaatsen.

‘die niettemin den speler geheel in beslag kan nemen’

De spelers gaan volledig op in het evenement, de muziek, het samenzijn, etc.

‘waaraan geen direct materiaal belang verbonden is, of nut verworven wordt’

Hier ben ik het gedeeltelijk mee eens. Naar mijn interpretatie maakt ‘het spelen’ geen winst, maar ‘de speler’ wel. Vrij letterlijk maken de artiesten winst in de vorm van geld. Het publiek in de vorm van ervaring. Ook in bijvoorbeeld videogames denk ik dat het vormen van een gemeenschap of het leren van een nieuwe vaardigheid nuttig kan zijn. Om een argument ten faveure van Huizinga te geven, zou je kunnen zeggen dat het concert geen invloed heeft op het dagelijks leven in de zin dat het bestaan van het concert geen verschil maakt in de samenleving, the big picture.

‘die zich binnen een opzettelijk bepaalde tijd en ruimte voltrekt’

Het evenement begint en eindigt op een bepaalde tijd. Ook is het stadion de specifieke ruimte die het ‘spel’ in beslag neemt.

‘die naar bepaalde regels ordelijk verloopt’

Er is zeker sprake van bepaalde spelregels die ik verder zal toelichten later in de blogpost.

‘en gemeenschapsverbanden in het leven roept, die zich gaarne met geheim omringen of door vermomming als anders dan de gewone wereld accentueren.’

De gemeenschap is vrij duidelijk. De ‘vermomming’ zou de merchandise van de band, bijvoorbeeld T-shirts, kunnen zijn die het publiek aan heeft tijdens het concert. Zo onderscheiden zij zich ‘als anders dan de gewone wereld.’

Er zijn nog een aantal (ludo)musicologische theorieën die ik graag wil aanhalen. Iedereen doet bijvoorbeeld mee met het spel maar er is maar één leider, de zanger. Hij dirigeert het publiek, bepaald inzetten en speelt met de muziek. Het publiek volgt.

Queen staat bekend om de interactie en vraag-en-antwoord. Een goed voorbeeld is het nummer We Will Rock You. Deze is speciaal geschreven zodat het publiek mee kon klappen.

Iedereen die betrokken is, werkt mee aan het proces, het spel en helpt bij een ‘succesvolle’ uitkomst (alea4) van het spel. Toch is elke uitkomst, elke uitvoering van het nummer, anders. Door de jaren heen hebben zij een soort geschiedenis opgebouwd, niet alleen als band maar ook in de vorm van optredens.

Door deze opgebouwde speciale band tussen publiek en Freddie Mercury is interactie op zo’n level mogelijk. Er is sprake van een belichaming van deze geschiedenis, ook wel ‘somatic historiography’[2] bij elk concert. Deze uitvoering is natuurlijk een representatie van alle vorige uitvoeringen van hetzelfde nummer. Er is een ongeschreven contract tussen publiek en performer waar iedereen van af weet maar niemand bewust van is. Door onder andere de ‘somatic historiography’ is er sprake van toe-eigening, een leider-volger principe binnen de uitvoering.[3]

Ik zou willen betogen dat door deze geschiedenis er ‘spelregels’ zijn ontstaan voor concerten van Queen. Een voorbeeld is dat de gitarist inademt op hetzelfde moment als dat de zanger zijn eerste zin inzet. Dit duidt op het feit dat beiden goed op elkaar ingespeeld zijn en de ‘regels’ kennen.

De tekst en het gitaarspel staan vast, misschien is zelfs de keuze om het publiek mee te laten zingen een voorbedachte keuze. Dit alles zorgt voor structuur (ludus[4]) binnen de uitvoering.

Kortom, Queen’s concerten hebben veel weg van spel. Het spelelement maakt dat deze uitvoeringen uniek zijn. De hechte band tussen performers en publiek maakt dit mogelijk en zorgt ervoor dat onder andere Love of My Life een one of a kind nummer is.

Yvette van Dusschoten

[1] Kamp, Summers, Sweeny. 2016

[2] Gaunt. 2006

[3] Sicart, Miguel. 2014

[4] Caillois, Roger. 1958

0 notes

Text

Crypt of the Necrodancer: Musical Gameplay in Immersive Videogames

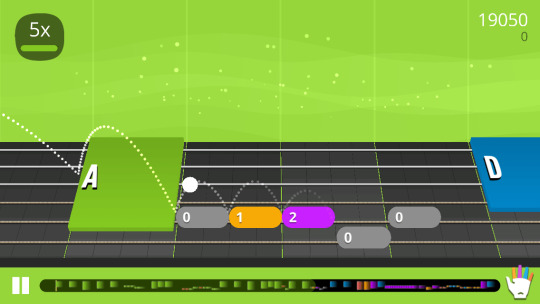

Image 1: Screenshot of a Crypt of the Necrodancer zone 4, level 1

Among the endless videogames that are displayed on the infinite webpages of Steam you might someday stumble upon a hidden gem. <1> For me this hidden gem was the indie videogame Crypt of the Necrodancer in which you control a character named Cadence who’s heart has been ripped out by the ‘necrodancer’ and bound to the rhythm of his music. She is then forced to fight monsters in his crypt while searching for her lost father and her own heart. Thus the main mechanics of the videogame consist of moving along to the beat while slaying monsters and obtaining powerful items. The player is required to carefully listen to the music in order to progress which makes playing along to music a core gameplay mechanic as well. Upon finding this very unique rhythm based game it sparked both my musicological and gaming interests. Therefore it is an excellent example of a ludomusical object which entangles an interesting combination of musical performance and gameplay.

Music, videogames and play

Ludomusicology is positioned as the study of the human involvement with music and the concept of ‘play’. Whereas the term of ‘ludomusicology’ originally implied to consist of the study of music within videogames, Roger Moseley argues differently. In an attempt to test Guitar Hero and Rock band from a ludomusicological perspective, he explored how music can be implemented into a gameplay mechanic. He emphasizes on the importance of ‘playing’ or ‘performing’ music in digital games in order to understand it, which contrasts research of text-based objects. Thus rephrasing the meaning of ludomusicology and how it can offer new perspectives to look at any kind of music within any form of ‘play’. In this case study I will explore different characteristics of play within videogames as described by Moseley, in his turn adopting it from Callois’ refinements of Huizinga’s identification of the components of play. <2> In order to elaborate more on the unique musical gameplay aspect, I would additionaly like to involve theories about ‘gamic actions’ written by Alexander Galloway. <3>

Firstly Callois describes four different categories for understanding games: agôn, alea, mimicry, and ilinx. Agôn covers the competitive aspects of play which, in terms of music, mostly refers to skill or popularity. When comparing this to digital games it mostly covers any game with a competitive multiplayer mode however Crypt of the Necrodancer only includes a cooperative multiplayer mode. Alea covers the chance-based aspects of play which is present in the randomly generated levels of Crypt of the Necrodancer, though it does not affect the music or vice versa. Thus these concepts do not touch upon the ludomusicological aspects of my case study. Furthermore mimicry refers to the simulation and playful imitation which is created by the gameplay and the music. Ilinx refers to the thrilling experiences of play which can be caused by physical activities. This is evoked in Crypt of the Necrodancer by making the player move to the rhythm of the music while being pressured to slay monsters to survive. The last two concepts of mimicry and ilinx are mostly applicable to Crypt of the Necrodancer as a ludomusical object and simultaneously the reason why this videogame is so unique. <4>

Furthermore Alexander Galloway offers a different perspective on gameplay in which he describes games as action-based media divided in two artificial types: players actions and machinic actions. These types of action are unified through the gameplay of a videogame where the player engages with a machine. Gamic actions take place outside our reality within the immersive videogame world resulting in a distinction between ‘diegetic’ and ‘nondiegetic’ actions. These terms are adopted from film and literary theory with slight differences, since videogames obviously differ from non-action-based media. In some cases it might be difficult to determine the distinction between diegetic and nondiegetic gamic action since the two are ingeniously intertwined within well executed game continuity, which is also the case in Crypt of the Necrodancer.

Musical gameplay in Crypt of the Necrodancer

Image 2: Crypt of the Necrodancer main menu

Among Galloways four types of gamic actions there is one in particular, the ‘diegetic operator act’, that helps to understand the interesting musical gameplay of Crypt of the Necrodancer. Diegetic operator acts are gamic actions that take place within the diegetic immersive videogame world and are executed by the player. These acts can occur in two different categories: move acts or expressive acts. Move acts determine the physical position of a playable character within a videogame, whereas expressive acts cover all of the other acts such as select, attack, open, pick up etc. <5> In Crypt of the Necrodancer these two categories are merged into one since you use your characters position to do every other act like open chests, pick up items, select levels or attack monsters. As a player you have to perform all these gamic actions to the rhythm of the music. It is this type of gamic action, provided by the machine and the game designers, that make musical gameplay possible within an immersive videogame world.

This immersive videogame world of Crypt of Necrodancer is what sets it apart from other rhythm games like Guitar Hero or Rock Band. Despite Moseley’s view on the mimicry of such games portraying the life of a Rockstar, I argue this to be significantly different from Crypt of the Necrodancer. <6> The objective within Guitar Hero is to perform a song that parallels the goals of a Rockstar. However in Crypt of the Necrodancer the players’ goal is not to perform music, but to beat the Necrodancer. There is a fictional world created around the musical gameplay in which the player has to pay close attention to the music while having another objective in mind. The player’s performance within this fictional world is partially influenced by the Ilinx aspect of the game. In Crypt of the Necrodancer the player is pressured to move to the beat using their fingers on a keyboard while simultaneously fighting monsters, who in turn move to the music with their own patterns. Thus the thrilling experience of this videogame is caused by the pressure of making precise movements to music with the player’s physical body.

Conclusion

Crypt of the Necrodancer is without a doubt a unique rhythm game in which musical gameplay plays an important role. It gives the player an objective within a fictional world which can be achieved by listening to and following music contrasting rhythm games like Guitar Hero or Rock Band. Music as a gameplay mechanic is provided by the fusion of move acts and expression acts, which make it easier to focus on music while playing the videogame. The rules of this game implement music in an ingenious way which can be explored further with concepts such as ‘procedural rhetoric’, written by Ian Bogost, which I might use in future research. For now I would like to conclude that Crypt of the Necrodancer is a ludomusical object containing musical gameplay within an immersive videogame world.

<1> Steam is a distribution platform for digital videogames founded by Valve Corporation which launched in 2003.

<2> Roger Moseley, “Playing Games with Music (and Vice Versa): Ludomusicological Perspectives on Guitar Hero and Rock Band,” in Taking it to the Bridge: Music as Performance, ed. Nicholas Cook and Richard Pettengill (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 283-284.

<3> Alexander R. Galloway, “Gamic Action, Four Moments,” in Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2006), 1-38.

<4> Roger Moseley, “Playing Games with Music (and Vice Versa): Ludomusicological Perspectives on Guitar Hero and Rock Band,” in Taking it to the Bridge: Music as Performance, ed. Nicholas Cook and Richard Pettengill (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 287-290.

<5> Alexander R. Galloway, “Gamic Action, Four Moments,” in Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2006), 1-38.

<6> Roger Moseley, “Playing Games with Music (and Vice Versa): Ludomusicological Perspectives on Guitar Hero and Rock Band,” in Taking it to the Bridge: Music as Performance, ed. Nicholas Cook and Richard Pettengill (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 287-290.

0 notes

Text

Het Culturele Geheugen van de Jazz Trompet

In deze blogpost behandel ik de trompet in een jazz context als een ludomuzikaal object. Op de eerste plaats bespreek ik jazzmuziek als een vorm van cultureel geheugen aan de hand van enkele ideëen over ‘signifying’ van Ingrid Monson en Kyra Gaunt. Vervolgens laat ik zien hoe men speltheoriën op deze muziek kan loslaten met als voorbeeld de muziek van Miles Davis op enkele bepalende momenten in zijn carrière.

Signifying is een concept dat met name voorkomt in de linguïstiek. Het wordt vaak gebruikt om een vorm van verbaal duelleren aan te duiden die veel voorkomt in Afro-Amerikaanse cultuur.[1] In deze verbale duellen staat een niveau van ‘cool’ en creatief reageren op plagerijen en uitdagingen bovenaan. Het gaat erom dat men gepast reageert op een uitdaging zodat de interactie speels blijft. In deze interacties zit echter een constante dreiging van aggressie. Als er niet goed gereageerd wordt of de ontvanger van een opmerking kiest hiervoor kan de speelsheid snel omslaan in woede of geweld. Ingrid Monson past deze term toe op jazzmuziek in haar boek Saying Something. Zij doet dit door de focus te leggen op het belang van reageren in Afro-Amerikaanse muziek.[2] Een bekende vorm hiervan is de call-and-response techniek die vaak wordt toegepast in de jazz waarbij een muzikant een motief speelt (vaak geïmproviseerd) waar een andere muzikant op moet reageren. Monson herkent signifying in deze interactie aan de manier waarop bepaald wordt welke muzikale motieven overgenomen worden en welke genegeerd worden. Als een muzikant gepast reageert op een muzikaal motief en laat zien dat hij geluisterd heeft naar wat er voor hem gespeeld werd is er meer kans dat de volgende muzikant dit motief zal overnemen en erop zal uitbreiden. Als een muzikant echter reageert door iets te spelen dat totaal losstaat van het voorgaande wordt dit vaak bestempeld als ‘vooraf ingestudeerd’ en daarom genegeerd.

Door deze definitie van signifying en de manier waarop het muzikaal terugkomt in de jazz kan men stellen dat jazz op deze wijze een onderdeel van Afro-Amerikaanse cultuur op heeft genomen in de muziek. Dit is slechts één van de manieren waarop jazzmuziek dit culturele geheugen belichaamt. Een andere auteur die Afro-Amerikaans cultureel geheugen aan muziek verbindt is Kyra Gaunt met haar boek The Games Black Girls Play. Hierin werkt zij een theorie uit waarin ze stelt dat Afro-Amerikaanse meisjes door middel van spelletjes als handjeklap en touwtjesspringen een zwart cultureel geheugen belichamen. Tegelijkertijd performen zij hun zwarte, vrouwelijke identiteit en behouden zij door spel hun cultuur.[3] Dit toont aan dat spel en muziek beide van groot belang zijn om een cultureel geheugen in leven te houden.

Nu dat we gezien hebben wat de rol van jazz is in het creëeren en belichamen van een cultureel geheugen, gaan we verder naar de volgende vraag: Wat is er ludisch aan jazz en de jazz trompet? Om de trompet en het spelen van de trompet in een jazzcontext te bespreken als een ludomuzikaal object kunnen we de drie verschillende soorten regels van Salen & Zimmerman toepassen.[4] Salen & Zimmerman onderscheiden drie soorten spelregels, op de eerste plaats de ‘operational rules’. Dit zijn de regels met betrekking tot de werking van het spel, de letterlijke spelregels. In het geval van de trompet in een jazz context kan men dit zien als de muzikale regels; de ideëen over tonaliteit en samenspel die heersend zijn in een bepaalde jazzstroming. Ten tweede spreken Salen & Zimmerman over ‘constituative rules’. Dit gaat, bij videospellen, over de technische werking van de console. Hiermee wordt puur de technische capaciteiten bedoelt. Bij de trompet zou dit dus gaan over de werking van de trompet zelf. Als men er op een bepaalde manier in blaast komt er geluid uit en dit geluid kan aangepast worden door te variëren in lipspanning en door de verschillende ventielen te gebruiken. Als laatste worden de ‘implicit rules’ genoemd. Dit zijn de ongeschreven regels van een spel. Bij de trompet in een jazzcontext is dit toe te passen op de ongeschreven sociale regels bij een jamsessie. Wanneer krijgt iemand een solo? Hoe lang gaat deze solo duren? Wat is een ‘goede’ solo? Dit zijn allemaal regels die niet van tevoren besproken worden maar waar een geoefende jazzmuzikant zich toch aan weet te houden.

Een andere manier waarop jazz ludisch is kan ik laten zien door jazz te bekijken op een iets grotere schaal dan een jamsessie, namelijk enkele momenten uit de carrière van een van de meest invloedrijke jazzmuzikanten uit de twintigste eeuw, Miles Davis. Davis speelt volgens velen een controversiële rol in de ontwikkeling van de jazz, met name in zijn latere jaren. In 1969 bracht Davis het album In a Silent Way uit.[5] Dit werd een album met veel elektronische invloeden en grote stappen die hem uit de wereld van de traditionele jazz namen. Dit werd hem lang niet door iedereen in dank afgenomen. Veel muziekcritici beschuldigden Davis ervan dat hij zijn ‘soul’ verloren zou zijn door deze richting op te gaan.[6] Deze reactie op Davis’ nieuwe richting wil ik vergelijken met het idee van de spelbreker volgens Johan Huizinga in zijn boek Homo Ludens.[7] Huizinga beschrijft de spelbreker als volgt: “Door zich aan het spel te onttrekken, onthult hij de betrekkelijkheid en de broosheid van die spelwereld, waarin hij zich tijdelijk met de anderen had opgesloten. Hij ontneemt aan het spel de illusie, inlusio, letterlijk “inspeling”, woord zwaar van beteekenis. Daarom moet hij vernietigd worden, want hij bedreigt het bestaan der spelgemeenschap.” De spelwereld in dit geval is de wereld van de moderne jazz (lees Bebop en Cooljazz) waar Miles Davis zich tot dan toe binnen ontwikkeld had. Op het moment dat Davis uit deze wereld stapt door nieuwe muzikale invloeden toe te passen en zijn vocabulair uit te breiden laat hij zien dat jazz meer kan zijn dan de in die tijd welbekende Bebop en Cooljazz. Met name door het betrekken van elektronische geluiden en rock- en funk invloeden wordt Davis gezien als spelbreker en voelen verscheidene critici zich genoodzaakt om hem te ‘vernietigen’ met hun recensies van zijn albums In a Silent Way en Bitches Brew.

Kortom, Jazz en de jazz trompet hebben enkele duidelijke ludische kwaliteiten en spelregels die gebroken of nageleefd kunnen worden. Mede door deze spelaspecten belichamen ze een essentieel onderdeel van het Afro-Amerikaanse cultureel geheugen en dragen ze bij aan de vorming van een Afro-Amerikaanse identiteit in een nieuwe generatie.

[1] Ingrid Monson, Saying Something: Jazz Improisation and Interaction, (University of Chicago Press, 1997), p.86-87.

[2] Monson, Saying Something, p.88-89

[3] Kyra Gaunt, The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes From Double-Dutch to Hip-Hop, (New York University Press, 2006).

[4] Eric Zimmerman, Katie Salen, Rules of Play: game design fundamentals, (MIT Press, 2003).

[5] Miles Davis, Quincy Troupe, Miles: The Autobiography, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), p. 281-287.

[6] Gary Tomlinson, ‘Cultural Dialogics and Jazz: A White Historian Signifies’ in Black Music research Journal vol. 11 no. 2, (University of Illinois Press, 1991), p.249-251.

[7] Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: Proeve Eener Bepaling van het Spel-Element der Cultuur, (Amsterdam University press, 1950), p. 39.

0 notes

Text

Yousician: an app to learn an instrument, or more?

By Ivana van der Zant

So, lately in quarantine I’ve been sucked into the YouTube-wormhole. It started out by just listening some music but then the YouTube-wormhole got me looking at all my favorite 80s videoclips for the one-thousandth time. All of a sudden it was dark outside and I realized I wasted all day watching L.A. Guns, Def Leppard and Whitesnake perform their songs and it made me realize I could have been more productive. I decided to do so the next day. I needed to up my guitar skills, so I started following tutorials on YouTube, of all my favorite songs, when I got the millionth ad of that day, but this time the ad was from an app called Yousician. An app in which you can learn guitar in an easy and structured way.

I was interested right away, because well, maybe learning guitar in a structured way was more productive than moving from one song to another. The ad told me what this app is all about, you get real time feedback and instructions to help you improve, set goals, record your progress and learn the guitar, all at your own pace. It has been designed by experts to keep you motivated whilst having fun when you learn. The app is also your personal music tutor:

“Yousician is an educational app with a game component that helps beginners to learn guitar, piano, bass and ukulele, and supports professional musicians in their daily practice”. <1>

I decided to try the app out for myself, to see what about this apps make you learn and play a game at the same time, ultimately making it a ludo-musical object. When starting the app you need to create an account and buy a one month membership in order to be able to use your seven day free trial as they promise you. Once you’ve had the whole process of choosing your instrument and you skill-level, you have to tune your guitar to standard tuning and plug your electric guitar into an amp in order for the app to be able to hear what you’re playing. But then, finally, the fun starts and you get rewarded by the first video. This video starts at the very basics of playing guitar, it explains how to tune your guitar, where the strings are and ultimately how the app works. Then you get the first exercise, playing ‘Seven Nation Army’ on two open strings, which, of course, is not the official tab of the song, but will do for now. Right away this app gave me the impression that these first exercises were more about learning how the app works and your timing than the actual playing and learning.

The further you get in your lessons, the more options you get. You can play more and more songs, you can work on different parts of the songs separately, change the speed of the song to a pace you’re comfortable with and you can work on your listening skills. Something I wasn’t expecting, but you can also learn all about the theory behind music and ultimately get rewarded by earning points and stars, to get at higher levels and get more options.

In a sense, Yousician can be compared with the very popular game ‘Guitar Hero’, in which you can ‘be a rockstar’ by playing on a plastic guitar with a few brightly colored buttons.<2> The plastic guitar is the game controller and in front of you, you have your screen, where you can see a guitar-neck and the notes you are supposed to play, or which different colored buttons you need to hit on time.<3> In this game, can choose a variety of distinctive ‘guitar songs’ in disparate difficulty levels. On the screen the different colored ‘gems’ come towards you via ‘note tunnels’<4> and you need to hit them right on time. To make things more difficult, you also have a plastic whammy-bar and a bar in the middle that makes you be able to hold in a color and still play separate notes of the same color. The objective of this game is to get as good as possible at the songs, breaking your own high scores and end up being number one on the international leaderboard.<5>

The developers of Guitar Hero, later developed Rock Band 3, which invites up to seven people to form a band in order to perform rock songs. The old guitar console can still be used, but the builders of this game, developed more consoles, such as microphones, a drum kit and even a two octave keyboard. To play this game together it is required to have a certain level of rhythmic accuracy, but I do think that this game in general is based on a certain sense of rhythm, after all, you do need to push the buttons on time.<6>

In this way, I think Yousician is very similar to Guitar Hero, and might have been influenced by the game. Both Yousician and Guitar Hero are based around the same rhythmic basis. Even the in-game screen looks kind of similar. Although Yousician has a horizontal guitar neck and Guitar Hero has a vertical one, on both of the screens you see the notes/’gems’ that transport over the screen, you see which notes/buttons you should play, if you are in time or not, and of course the high score to keep it a bit more challenging.

Yousician screen

Guitar Hero screen

I think the difference between these two programs lies mainly on its intentions. Whereas Guitar Hero is more of a fun game to play, Yousician is more focused on learning the guitar and does so in a more playful, almost game-like way. But both do have a leaderboard in order for you to want to get better and better.

Ludomusicology

Ludology is the study of games, game players and its culture, it is also called game studies. Ludomusicology is kind of similar, but is mainly focused on the musicological part of games. Whether it be music in games, music made by games, but also music with game components and so forth. Roger Callois made his own gametaxonomy, he divides games into four different components, agōn (battle), ales (chance), mimicry (imitation) and ilinx (vertigo). In this taxonomy, he has a distinguish between ludus (game) and paidia (play).<7>

I think both Yousician and Guitar Hero fit very well in the agōn subdivision, both are focused on getting the highest score , whilst Yousician is more focused on defeating your own high scores, and ultimately getting better at playing the guitar, Guitar Hero is more focused on defeating the all-time high scores and become the highest ranked, and the best at the game. I also think that both Yousician and Guitar Hero fit best in the subdivision of ludus, both are very structured and are gradually increasing their level of difficulty. Although the focus, again, with Yousician is to learn to play the guitar better and with Guitar Hero is to defeat te all-time high scores.

I think Yousician is a good example of a ludomusicological subject, because it incorporates learning the guitar with a game component. We’ve seen that Yousician in some ways is compatible with Guitar Hero and whilst they have a lot in common, they also have their differences, mainly on where the focus of the game lies and what the actual intention of the game is.

<1> Yousician’s official YouTube channel in which they show the ad and what this app is all about: https://www.youtube.com/user/ovelinbird.

<2> Roger Moseley, “Playing Games with Music (and Vice Versa): Ludomusicological Perspectives on Guitar Hero and Rockband,” in Taking It to the Bridge: Music as Performance, ed. Nicholas Cook & Richard Pettengill (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 280-282.

<3> A YouTube video in which ‘GuitarHeroPhenom’ plays the song ‘Through the Fire and Flames’ at 100% Expert in Guitar Hero 3: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHRfbiwdheg.

<4> Roger Moseley, “Playing Games with Music (and Vice Versa): Ludomusicological Perspectives on Guitar Hero and Rockband,” in Taking It to the Bridge: Music as Performance, ed. Nicholas Cook & Richard Pettengill (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 281.

<5> A Wikipedia page on the subject ‘Guitar Hero’, which sums the game and its developers up: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guitar_Hero.

<6> Roger Moseley, “Playing Games with Music (and Vice Versa): Ludomusicological Perspectives on Guitar Hero and Rockband,” in Taking It to the Bridge: Music as Performance, ed. Nicholas Cook & Richard Pettengill (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 280.

<7> Roger Caillois, trans, Meyer Barash, Man, Play, and Games (Illinois: Illinois University Press, 2001).

0 notes

Text

TikTok Als Ludo-Muzikaal Object

Door Fariel Soeleiman

Nog enkele jaren geleden behoorde ik ook tot de generatie die met de nieuwste sociale media uitdagingen aan kwam wapperen. Maar intussen is er alweer een jongere generatie, namelijk de generatie Z, die het stokje heeft overgenomen, alhoewel ik mij niet kan herinneren het stokje ooit te hebben afgedragen. Het is zo’n “soepel” proces waarin je je bevindt in jouw twintigerjaren en je tot de ontdekking komt dat je ook “ouder” wordt. Hoewel, ik ook heb genoten van sociale media zoals Hyves en Hi5, moet ik eerlijk toegeven dat ik mijn piekjaren heb beleefd met platformen als Facebook en Instagram. Facebook is de afgelopen jaren geleidelijk gezakt in populariteit, maar Instagram, daarentegen, bleef juist bloeien, totdat die ook Facebook voorbijstreef. Ironisch genoeg is Instagram in 2012 overgekocht door Facebook, maar verder ontwikkeld als onafhankelijke app <1>.

Maar sinds een jaar is er een nieuwe app die de wereld heeft veroverd namelijk, de oorspronkelijke Chinese app, TikTok. TikTok, voorheen Musical.ly, is een videoapp waarin muziek een sterke rol speelt. Veel van de videovoorwaarden voldoen aan de wijlen app Vine. Vine was ook een immens populaire video app waarin humor een grotere rol speelde dan muziek. TikTok heeft haar plotselinge roem vooral te danken aan generatie Z en heeft zelfs al een verloren rechtszaak in Amerika aan haar naam hangen vanwege het schenden van privacy rechten van hun minderjarige gebruikers. Maar dat maakt ze op dit moment nog niet minder populair bij diezelfde minderjarige gebruikers <2>. Immers zijn het hun “vervelende ouders” die vooral klagen over de gevaren van de app voor naïeve brugklassers.

De app

Desalniettemin, is TikTok een geliefde mobiele app onder de jongeren van nu. Integendeel, beroemdheden en zelfs bedrijven volgden al heel snel met hun aanwezigheid op dit nieuwe platform. Enkele kenmerken van TikTok die zo aantrekkelijk blijken te zijn, zijn: de laagdrempeligheid van de videobewerking in de app, de integratie van beeld met muziek, de grote kans om viraal te gaan, en natuurlijk alle overige standaard sociale mediamogelijkheden zoals het delen, liken en reageren op elkaars video’s. Ook de interface is heel gebruiksvriendelijk voor jong en oud <3>.

Eén van de vele fenomenen op en van TikTok zijn de dansuitdagingen. Die dansuitdagingen worden uitgevoerd op: nieuwe onbekende nummers, nieuwe bekende nummers, oude onbekende nummers, oude bekende nummers, etc. Wat al enkele keren is voorgekomen, is dat zo’n dansuitdaging ervoor zorgt dat een (nieuwe) onbekend nummer viraal gaat en soms zelfs een officiële hit wordt. Het allereerste nummer waarmee dat gebeurde, was het country-hiphop nummer “Old Town Road” van Lil Nas X. Het nummer genoot plotselinge roem toen TikTokker Michael Pelchat een paar danspasjes met een vleugje humor had bedacht op het nummer en dat had gedeeld op zijn profiel <4>. Zijn TikTok-video sloeg zo goed aan dat meerdere gebruikers de danspasjes op het nummer uitvoerden, het een dansuitdaging werd, het daardoor op de eerste plek verscheen van de “Billboard Top 100” in 2019 en zeker zes weken daar bleef staan <5>.

youtube

Dansuitdaging: Savage Challenge

Eén van de, nog steeds, populaire dansuitdagingen waarop ik zal inzoomen, is de zogeheten #savagechallenge. De reden waarom ik het met een hashtag schrijf, is omdat die een belangrijke rol heeft in de app. Door zo’n tag toe te voegen, kunnen andere gebruikers jouw video ook vinden op de discover-pagina of met de zoekfunctie. Hoe meer mensen dezelfde tag gebruiken, hoe hogerop de tag komt te staan. Er is dan sprake van een trending topic wanneer op sociale media in korte tijd veelvuldig over een bepaald onderwerp wordt gesproken of, in TikTok’s geval, video’s worden gepost <6>. De #savagechallenge is momenteel niet meer trending, maar hypes van tegenwoordig duren maar enkele weken of zelfs dagen.

De #savagechallenge is gecreëerd door TikTok gebruiker @keke.janajaha, beter bekend als Keara Wilson, en gebruikt het nummer “Savage” van Megan Thee Stallion, een nieuwkomer in de muziekwereld. Binnen enkele dagen na de release van haar nummer, plaatste Wilson haar dansuitdaging op haar profiel en promootte die voor vijf dagen achter elkaar in de hoop dat een beroemdheid die zou oppakken en haar choreografie viraal zou gaan <7>. De dansuitdaging sloeg al aan bij andere TikTok gebruikers, maar uiteindelijk was het Stallion zelf die het oppikte en zelf ook een video deelde op TikTok waarin ze Wilsons choreografie uitvoerde. Toen ging het daadwerkelijk viraal en stond TikTok bol van de Savage challenges <8>.

youtube

Ludo-muzikaal object

Ludologie is de studie van spel, spelers en de cultuur daaromheen – ook wel game studies. Ludomusicologie is dus gericht op de rol en integratie van muziek in spel. Het spel mag allerlei vormen aannemen: digitaal, online, virtueel, fysiek, het maakt niet uit, zolang het maar samen werkt met muziek zoals onder andere GuitarHero. Maar ook spellen waarvan de muziek wordt beïnvloed door jouw spel gelden bijvoorbeeld in Super Mario Bros en Zelda <9>. Dit zijn de meer traditionele opties wanneer we denken aan spellen, maar er zijn nog een aantal andere soorten spellen die ik met behulp van enkele theorieën zal uitleggen en koppelen aan de TikTok app met de #savagechallenge als mijn casestudy.

Roger Caillois was een Franse socioloog die bekend was vanwege zijn eigenzinnige werk gefocust op spel. In zijn boek Man, Play and Games (1961) borduurde hij voort op de speltheorieën van de Nederlandse culturele antropoloog Johan Huizinga’s boek Homo Ludens (1938). In dit boek beargumenteerde Huizinga dat cultuur voortkomt uit spel en dat de kenmerken hiervan zijn dat: spel niet verplicht is, spel los staat van het dagelijks leven, spel grenzen heeft, spel uitgaat van bepaalde (spel)regels, en dat spel zorgt voor verbondenheid tussen de spelers. Dit alles vond, volgens Huizinga, plaats in de ‘toovercirkel’. De ‘toovercirkel’ heeft te maken met afscheiden van het spel en de “echte” wereld. Bijvoorbeeld, een toneel is een begrensde plek waarin het theaterspel plaatsvindt en daarbuiten vindt de “echte” wereld plaats zoals het publiek en de crewmedewerkers.

Caillois vormde hiermee zijn eigen speltaxonomie en verbreedde het spelbegrip met vier spelcategorieën: agõn (competitie), alea (kans), mimicry (imitatie), en ilinx (duizeligheid). Daar voegde hij nog een onderscheid aan toe namelijk ludus (structuur) en paidia (vrij). Enkele voorbeelden van spellen in deze categorieën zijn te zien in de onderstaande tabel <10>.

Nu ik wat meer achtergrondinformatie heb gegeven over de app TikTok en de speltheorie van Caillois, gaan we ons verdiepen in het ludo-muzikale van mijn casestudy. De dansuitdaging is een korte danschoreografie en heeft enige vaardigheden en/of oefening nodig, voordat je die kan uitvoeren. Hoe beter jouw vaardigheden, hoe sneller je het onder de knie krijgt. Dans kan je plaatsen bij meerdere categorieën, maar de primaire categorie zou zijn ilinx. Een combinatie is mogelijk met mimcry als je bijvoorbeeld karakters uitbeeldt in de dans en/of ook met agõn als je als professionele danser meedoet in danscompetities. In het laatste geval, behoort dans bij ludus, omdat de danscompetities expliciete regels heeft en dus voor structuur zorgt. Maar bij dansimprovisaties tijdens een freestyle avond, zou je dans ook bij paidia kunnen plaatsen.

De #savagechallenge past goed in het type paidia, omdat de uitdagingen voor plezier zijn, maar de gehele aard van de app TikTok neigt vooral naar het viraal gaan. Hierdoor kan je deze uitdaging ook plaatsen bij ludus, omdat Wilson gestructureerd aan de slag is gegaan om haar video viraal te laten gaan. Alhoewel, Wilson haar choreografie heeft bedacht door te improviseren, wat weer verwijst naar paidia, hebben TikTok gebruikers de exacte choreografie overgenomen door middel van oefening en dat verwijst weer naar ludus. Dit omdat de choreografie expliciete danspassen heeft die gevolgd moeten worden om mee te doen met de dansuitdaging. Daarnaast bestaat een uitdaging, in het algemeen, uit een aantal voorwaarden ofwel spelregels. Op basis daarvan passen alle dansuitdagingen op TikTok (inclusief mijn casestudy) in ludus in combinatie met mimcry, omdat de TikTok video pas viraal gaat wanneer veel TikTok gebruikers de video namaken.

Tevens is de ‘toovercirkel’ van toepassing op de #savagechallenge. Zoals ik al eerder vermeldde, heeft de ‘toovercirkel’ te maken met het afscheiden van het spel en de “echte” wereld. Deze dansuitdaging is gecreëerd voor een sociaal (mobiel) medium en daarmee scheid je de #savagechallenge af van de realiteit, omdat die in de virtuele wereld plaatsvindt. In de realiteit dans alleen en ziet niemand jou dansen. Pas als je jouw dansvideo uploadt en deelt met de virtuele wereld van TikTok, dans je “samen” met andere gebruikers en zien anderen dat je ook meedoet. Door jouw zichtbare deelname aan die ene uitdaging, draag je bij aan het viraal gaan van die uitdaging. Dit is dan ook een uitstekend voorbeeld van de participatiecultuur die sterk aanwezig is in hedendaagse media zoals TikTok.

Een andere kant van de ‘toovercirkel’ is de commerciële kant van TikTok. Alhoewel, TikTok oorspronkelijk is gestart als een app voor plezier, zijn er nu ook een aantal TikTok gebruikers die de app gebruiken voor zakelijke doeleinden. Hun TikTok activiteiten behoren nu dus ook tot hun werk. Een voorbeeld hiervan is Michael Pelchat die het nummer “Old Town Road” van Lil Nas X viraal liet gaan met zijn dansuitdaging en in een later stadium een geldbedrag ontving van de artiest als dank. Sindsdien maakt Pelchat betaald TikTok video’s voor artiesten die hun nummer meer bekendheid willen geven <11>. Zo zijn er nog een aantal TikTok gebruikers die geld verdienen aan het maken van (dans)uitdagingen voor artiesten. Volgens Huizinga en Caillois is spel iets fundamenteel anders dan werk en altijd “nutteloos”. Maar doordat deze TikTok gebruikers nu betaald reclame maken voor artiesten en hun muziek, zijn ze eigenlijk aan het “spelen” en tegelijkertijd aan het “werken”. Hierdoor vervaagt het onderscheid in de ‘toovercirkel’.

Al met al is TikTok een multi-inzetbaar platform en een veelzijdig ludomuzikaal object. Een virtuele plek om alle plezier en creativiteit los te kunnen laten samen met anderen, ongeacht leeftijd, en tegelijkertijd de mogelijkheid om ook geld te verdienen in de realiteit aan de participatiecultuur van hedendaagse media.

<1> Baer, Jay. 2018. 9 Reasons Instagram Will Overtake Facebook. Convince & Convert. Bloomington, Indiana: Convince & Convert, LLC. Geopend Mei 18, 2020. https://www.convinceandconvert.com/baer-facts/9-reasons-instagram-will-overtake-facebook/.

<2> Anderson, Katie Elson. 2020. „Getting acquainted with social networks and apps: it is time to talk about TikTok.” Emerald Insight (Emerald Publishing) 1-4. Geopend Mei 19, 2020. doi:https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1108/LHTN-01-2020-0001.

<3> Idem, 2-3.

<4> Always Smiling. “how’s this for a country boy #foryou #funny #dance #countryboy.”

TikTok, 16 februari 2019. https://www.tiktok.com/@nicemichael/video/6658388605418867974

<5> Anderson, Trevor, Gary Trust. “Winner's Circle: Lil Nas X's 'Old Town Road' Breaks

Record With 17th Week A top Billboard Hot 100.” Billboard, 29 juli 2019. https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/chart-beat/8524235/lil-nas-x-old-town-road-longest-number-one-hot-100.

<6> sd. Hashtag. Wikipedia. Geopend Mei 19, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hashtag.

<7> Jean-Philippe, McKenzie. 2020. There's Now A New "Savage Challenge" After Beyoncé's Remix. The Oprah Magazine. Hearst Magazine Media, Inc., 1 Mei. Geopend Mei 18, 2020. https://www.oprahmag.com/entertainment/a31932915/savage-challenge-megan-thee-stallion-lyrics/.

<8> Aderoju, Darlene. 2020. How Megan Thee Stallion Learned Her 'Savage Challenge' TikTok Dance While Social Distancing. People. Meredith Corporation, 23 April. Geopend Mei 18, 2020. https://people.com/music/megan-thee-stallion-savage-challenge-tik-tok/.

<9> Schuiling, Floris. 2020. “ Inleiding ludomusicologie.” Hoorcollege, Muziek, Spel en Uitvoering, Universiteit Utrecht, 14 Mei. Geopend Mei 17, 2020.

<10> Idem.

<11> Leight, Elias. “NiceMichael Made ‘Old Town Road’ a TikTok Hit. He’ll Do the Same for You – For a Price.” Rolling Stone, Mei 20, 2019. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/nicemichael-tiktok-lil-nas-x-flo-milli-837371/

1 note

·

View note

Text

De Film van Ome Willem: spel, improvisatie en interactie

Door Mirjam de Zwart

Hoewel het programma eerder stamt uit de kindertijd van mijn ouders dan uit de mijne, heb ik vroeger met veel plezier gekeken naar de avonturen van Teun, Toon en August in De film van Ome Willem. De Film van Ome Willem werd in de periode 1974 tot 1989 door de VARA op televisie uitgezonden. Een aflevering duurde gemiddeld vijfentwintig minuten en bestond uit een sketch over een onderwerp wat kinderen aansprak. Tijdens de sketches werden vaak een aantal liedjes gezongen door de acteurs, waarin zij zongen over een onderwerp dat aansloot op het thema van de aflevering. Wat mij het meest bij is gebleven uit de show is het beginlied waarin Ome Willem samen met de Geitenbreiers het publiek, jonge kinderen van ongeveer zes jaar, welkom heet. Improvisatie en spel, aspecten die je als kind niet snel herkent, spelen bij de acteurs en muzikanten een grote rol bij deze uitvoeringen. In deze blogpost zal ik het lied bespreken aan de hand van de concepten van Roger Caillois, Miguel Sicart en Johan Huizinga om zo de spelelementen aan te kunnen die dit lied tot een ludo-muzikaal object maken.

Roger Moseley gebruikt in zijn artikel de concepten van de speltaxonomie van Roger Caillois <1>, om de verschillende vormen van spel uit te lichten.<2> De verdeling agôn, alea, mimicry en ilinx, oftewel competitie, kans, imitatie en duizeling, zijn bovendien ook nog onder te verdelen in paidia (vrij spel) en ludus (structuur). <3> Deze concepten zijn niet alleen toe te passen op games, maar ook op muziek en op de uitvoering hiervan.

Allereerst is mimicry erg toepasbaar. Het lied wordt gezongen en geleid door Edwin Rutten, in de rol van Ome Willem. Rutten, die naast acteur ook jazzzanger en muzikant is, begeleidt zichzelf op het drumstel. De rest van de begeleiding wordt uitgevoerd door de Geitenbreiers band, een jazzcombo van accordeon, contrabas en piano. Hoewel de muzikanten van dit combo soms worden aangesproken als hoofd-, grijze-, of papjesgeitenbreier, treden ze tijdens de voorstelling niet buiten zichzelf en zijn ze gewoon Harry Bannink, Harry Mooten en Frank Noya. Het beginlied heeft een vaste vorm, het valt dus onder ludus. Het lied bestaat uit zes coupletten, die telkens kort worden onderbroken met gesproken zinnen tussendoor. Hoewel de tekst van de coupletten vast staat, worden de zinnen tussendoor bij verschillende uitvoeringen wel verschillend geformuleerd.

De tekst van het lied staat dus zo goed als vast en wordt er bijna niet vanaf geweken. In de muziek zelf is er wat meer ruimte voor improvisatie. Hoewel alle coupletten bestaan uit dezelfde akkoorden, heeft elk couplet zijn eigen karakter. Er wordt binnen deze kleine jazz compositie veel afgeweken met versierende noten en ritmes, zoals triolen. Door te improviseren op het akkoorden schema krijgt het lied een speels karakter. Deze improvisatie valt nog steeds binnen de kaders van het akkoorden schema, en is dus niet te vergelijken met bijvoorbeeld een jamsessie. Toch is geen enkele uitvoering gelijk en zit er een element van onvoorzienigheid in, wat onder te verdelen valt bij alea (kans).

Een ander eigenschap wat het lied speels en veelzijdig maakt zijn de tempowisselingen. De eerste vier coupletten worden gespeeld in een gemiddeld tempo van ongeveer 120 bpm. Aan het eind van het vierde couplet is het hoogtepunt bereikt (“lust jij ook een broodje poep?”). In het couplet wat hierna volgt is het tempo twee keer zo snel, waarschijnlijk om de aandacht van de kinderen weer terug te krijgen en het lied gaande te houden. Het laatste couplet wordt daarentegen weer twee keer zo langzaam gespeeld, om aan te geven dat Ome Willem er maar mee stopt, hij zegt immers alles verkeerd:

‘K geloof dat ik maar niets meer vraag

Het is wel weer genoeg vandaag

Ome Willem stopt er mee

Knip, knap, knee (pada dum)

Deze snelle tempowisselingen en de kleine improvisaties zorgen ervoor dat het lied ondanks de eenvoudige melodie en tekst afwisselend blijft. Het publiek wordt zo helemaal in het verhaal en de performance getrokken. Door binnen de structuur toch ruimte te maken voor kleine aanpassingen is er binnen de ludus ook paidia te zien. Er is een balans tussen structuur en improvisatie in het spel.<3> Er ontstaat een spel bij de muzikanten omdat ze aan de ene kant de regels in acht nemen en opvolgen, maar ze aan de andere kant ook kapotmaken door te improviseren. Deze theorie van Miguel Sicart is niet alleen toe te passen op het spel van de muziek zelf, maar ook op het spel dat wordt gecreëerd door de muziek. Dit kan worden uitgelegd aan de hand van de Toovercirkel van Johan Huizinga. <4> In het programma wordt een andere wereld gecreëerd, namelijk het huis van Ome Willem, waar hij samen met Toon, Teun en August woont. De dingen die zich hier afspelen hebben een eigen realiteit en breken met de regels van het alledaagse, zonder dat het compleet afstand doet van de echte realiteit. Er zijn ook andere regels. De kinderen zijn bijvoorbeeld verkleed en bij het introlied mogen ze meezingen en weten ze precies wanneer ze moeten reageren op een vraag van Ome Willem:

Wat ik ook nog vragen wil,

Is er hier een krokodil? (Respons van publiek: nee!)

Wou dat ik een ijsje had

Ijs met slagroom

Lusten jullie dat? (respons van publiek: ja!)

Snap het al daar smul je van

Lust je ook wel bloemkool dan? (Frank Noya: met een papje, met een papje, met een papje)

Door in De Film van Ome Willem een eigen wereld te creëren voelen kinderen zich betrokken en ontstaat een interactieve sfeer.

Naast het dat de voorstelling interactief en vermakend is, zit er ook een didactisch element in het programma. Het verhaal heeft altijd een happy end, waarbij conflicten tussen de acteurs zijn uitgepraat en de persoon die zich niet aan de regels heeft gehouden, wat vaak ome Willem is, op zijn plek is gezet. Dit is ook duidelijk zichtbaar in het openingslied, waar Ome Willem wordt gecorrigeerd door Harry Bannink:

Ome Willem: Luister even wat ik roep, lust jij ook een broodje poep?

Harry Bannink: Bah ome Willem, dat vinden de kinderen vies!

Ome Willem: Is dat vies? Mag ik dat niet zeggen?

Bannink: Nee, Ome Willem!

Ome Willem: Foei ome Willem! (Hij “slaat” zichzelf op het hoofd met zijn drumstokjes)

Ome Willem: Stomme Ome Willem!

Door Ome Willem dit te laten zeggen en de belerende toon van Bannink die daarop volgt leren de kinderen dat het niet netjes is om “een broodje poep” te zeggen. Zo wordt er door middel van muziek en spel een bijdrage geleverd aan de opvoeding.

Wat maakt het openingslied van De Film van Ome Willem ludo-muzikaal? Binnen de muziek zelf is er een goede balans tussen structuur en improvisatie, waarbij er binnen de ludus ruimte is voor paidia. Dit geldt ook voor de liedtekst, die bovendien samen met de muziek ook zorgt voor interactie tussen Ome Willem en de kinderen in het publiek en voor de televisie. Er ontstaat een Toovercirkel: een wereld van het programma die breekt met de regels van de realiteit, maar er niet helemaal vanaf wijkt. Bovendien zijn de concepten van de speltaxomonie indeling van Roger Caillois, mimicry en alea te herkennen in de uitvoeringen. De elementen van interactie, vermaak en opvoeding in combinatie met professionele en getalenteerde uitvoerders hebben naar mijn mening geresulteerd in een van de beste kinderprogramma’s ooit gemaakt voor de Nederlandse televisie.

Liedtekst <6>

Ome Willem: Geef mekaar maar even een klein kusje. En dan nu, aan het werk!

(4/4 maat)

Luister even wat ik vraag

Luister wat ik vraag vandaag

Zeg maar ja of zeg maar nee

Doe maar mee

Zeg eens even allemaal

Zijn er hier ook meisjes in de zaal? (response van publiek: ja! )

Ach dat doet mij veel plezier

Zijn er ook wel jongens hier? (response van publiek: ja!)

Wat ik ook nog vragen wil,

Is er hier een krokodil? (Response van kinderen: nee!)

Wou dat ik een ijsje had

Ijs met slagroom

Lusten jullie dat? (response van publiek: ja!)

Snap het al daar smul je van

Lust je ook wel bloemkool dan? (Frank Noya: met een papje, met een papje, met een papje)

Ome Willem: Rakkers, bloemkool met een papje is wel lekker, maar weten jullie wat ik het allerlekkerst vind?

Luister even wat ik roep, lust jij ook een broodje poep?

Harry Bannink: Bah ome Willem, dat vinden de kinderen vies!

Ome Willem: Is dat vies? Mag ik dat niet zeggen?

Bannink: Ja, Ome Willem, dat is heel vies!

Ome Willem: Foei ome Willem! (Hij “slaat” zichzelf op het hoofd met zijn drumstokjes)

Stomme Ome Willem!

(Twee keer zo snel)

Jullie wonen in een huis

Heb je ook een tafel thuis? (Respons van publiek: Ja!)

Staat er op die tafel dan droog water waar je mee douchen kan? (dit is elke aflevering een ander voorwerp dat niet bestaat en onlogisch is, dit leidt het thema van de aflevering in)

Bannink: Dat bestaat niet, dat bestaat niet, dat bestaat niet ome Willem!

(Ome Willem “slaat” zichzelf opnieuw op het hoofd met zijn drumstokjes)

Ome Willem: Stomme Ome Willem!

(Vertraagd)

‘K geloof dat ik maar niets meer vraag

Het is wel weer genoeg vandaag

Ome Willem stopt er mee

Knip, knap knee (pada dum)

<1> Roger Caillois, trans. Meyer Barash, Man, Play, and Games (Illinois: Illinois University Press, 2001).

<2>Roger Moseley, ‘Playing Games with Music (and Vice Versa): Ludomusicological Perspectives on Guitar Hero and Rock Band,’ in Taking it to the Bridge: Music as Performance, ed. Nicholas Cook, and Richard Pettengill (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2013).

<3> Caillois, Man, Play and Games, 36.

<4> Miguel Sicart, “Play Is,” in Play Matters (Cambridge, MA; Londen: MIT Press, 2014), 9.

<5> Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: Proeve Eener Bepaling van Het Spel-Element Der Cultuur (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010): 27.

<6>Gebaseerd op het introlied van aflevering ‘August moet in bad’ uit 1987:

“De Film van Ome Willem-August moet in bad” YouTube Video. 21:35. Geplaatst door: Deltadesignart, 27 oktober 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZxGuxNkkaOA&t=315s.

0 notes

Text

Vele drummers maken licht werk

Hoe 2000 drummers op het strand samen kwamen om muziek te maken

Door Bente van der Zalm

Op 9 september 2018 vond op Scheveningen een bijzonder spektakel plaats. Er verzamelde zich daar namelijk 2000 drummers om samen muziek te maken. Het initiatief kwam van Cesar Zuiderwijk, de drummer van de Golden Earring. Het evenement droeg de naam ‘Four Horizons - 2000 drummers aan zee’ en was een onderdeel van het verjaardagsfeestje van Scheveningen, dat haar 200 jarige bestaan vierde. <1> Eerder had Zuiderwijk al het project ‘1000 drummers aan de Maas’ voor de Wereldhavendagen in Rotterdam bedacht, maar voor deze gelegenheid pakte hij het nóg groter aan. De ‘Four Horizons’ staan voor de vier windrichtingen, die elk worden weergegeven door vijfhonderd drummers. Onder Noord vallen Europa en de Verenigde Staten, onder Oost valt Azië, Zuid-Amerika valt onder Zuid en Afrika onder West. Al deze windrichtingen hebben van nature hun eigen percussie-instrumenten; Noord heeft drums en snares, en zuid bijvoorbeeld shakers, repiniques en surdo’s. Voor elke compositie spelen de vier windrichtingen een eigen partij. Per persoon kon het op deze manier eenvoudig blijven, dus voor veel mensen speelbaar, maar omdat er zo veel mensen waren klonk het geheel al snel ingewikkeld. De toegang voor zowel de toeschouwers als de deelnemers was gratis en iedereen kon meedoen als die maar kon drummen en een instrument om te bespelen had. Om mee te doen was het belangrijk voor de drummers om van te voren een eenvoudig ritme in te studeren zodat het geheel niet in een complete chaos resulteerde. Het optreden duurde maar liefst twee uur. <2>

Zodat dit goed kon verlopen was structuur vereist. Deze structuur werd vormgegeven doordat Cesar Zuiderwijk de rol van dirigent op zich nam en werd geholpen door het feit dat de participanten van te voren een ritme hadden geleerd dat ze konden spelen wanneer dat aan hen gevraagd werd. Deze ritmes waren samen met instructievideo’s van tevoren online te vinden. <3> Een belangrijk detail bij deze ritmes is dat ze allemaal in vierkwartsmaat gespeeld dienen te worden. Voor windrichting Noord is dat vrij vanzelfsprekend, omdat de meeste muziek in deze gebieden in vierkwartsmaat staat en dat dus een zeer gebruikelijke maatsoort is, maar voor Afrikaanse of Zuid-Amerikaanse muziek is dat bijvoorbeeld veel minder gebruikelijk. Toch is het voor het goed samenspelen wel praktisch dat alles in vierkwartsmaat genoteerd staat, want de kans dat de uitvoering in de soep loopt is dan aanzienlijk kleiner. Tegenover deze vooraf ingestudeerde ritmes stond een onderdeel dat bestond uit improvisatie. Hiervoor was de rol van de leider nog belangrijker. Zuiderwijk gaf steeds per onderdeel aan wat het publiek moest doen. Zo kon bijvoorbeeld het geluid van de zee worden geïmiteerd, doordat de verschillende werelddelen na elkaar een roffel van een verschillende duur uitvoeren. Voor het van te voren ingestuurde ritme was het van groot belang dat dit niet te ingewikkeld was. Op deze manier kon iedereen het uitvoeren en hoorde je nog duidelijk het ritme terug wanneer het door tweeduizend drummers tegelijk gespeeld werd. Hierover schreef Zuiderwijk: “Dit zijn natuurlijk niet de moeilijkste partijen, maar met 2000 drummers klinkt het waanzinnig!”.

Volgens Huizinga is spel de volgende dingen: vrij, onecht, begrensd en ordelijk en creëert het gemeenschap. In het geval van de drummers gelden al deze eigenschappen. Het is vrij op de manier dat iedereen naar deze bijeenkomst is gekomen uit eigen wil en niemand gedwongen is. Het is onecht op de manier dat er zelden zo veel drummers bij elkaar zijn, want veel drummers zijn meestal de enige drummer op het podium. Het is begrensd, omdat het zich duidelijk op een begrensd gebied afspeelt; op het strand, binnen hekken. Het is ordelijk, omdat het letterlijk geordend is door de dirigent en de mensen die over vakken zijn verdeeld, maar ook omdat er een utopische werkelijkheid is op het moment: alle werelddelen spelen samen één muziekstuk. Om dezelfde reden creëert dit spel gemeenschap. Het gevoel van saamhorigheid is groot wanneer je allemaal hetzelfde doel hebt en samen met anderen muziek maakt. <4>

Er is sprake van veel interactie tijdens de uitvoering. Zo is er bijvoorbeeld interactie tussen Zuiderwijk en het publiek, tussen de vier windrichtingen, tussen de drummers op het podium en Zuiderwijk, tussen de drummers op het podium zelf en tussen de participanten. Iedereen moet constant kijken en luisteren en daar vervolgens op reageren. Dit is misschien nog wel het beste te merken bij de compositie Vraag & Antwoord, waar Zuiderwijk een ritmisch motief speelt en het publiek dat naspeelt. Hiervoor is het uiterst belangrijk om te luisteren naar wat er voorgespeeld wordt en dat je hierop kan reageren, omdat het anders in een chaos resulteert. Ook in Waves, waar het geluid van de golven van de zee wordt nagedaan, is interactie uiterst belangrijk, omdat Zuiderwijk hier één voor één de windrichtingen aanwijst en die leden van de verschillende windrichtingen op het juiste moment daarop moeten reageren.

Om het specifieker te maken, volgt hier een voorbeeld dat illustreert welke partij iedere groep of instrumentensoort speelde. Het spektakel werd afgesloten met het nummer Radar Love. Dit nummer stond ook al centraal bij ‘1000 drummers aan de Maas’ en dat ging toen zo goed dat Zuiderwijk en de Golden Earring het nog een keerde wilde proberen uit te voeren, maar nu met twee keer zo veel drummers en dit maal ook twee bands op het podium. In tegenstelling tot alleen de Golden Earring op het podium, was nu ook de Belgische rockgroep Triggerfinger aanwezig om het nummer uit te voeren. De bladmuziek voor percussie is te zien op de afbeelding. Het nummer is origineel van de Golden Earring, een rockformatie. In veel rock- en popmuziek ligt het accent van de maat op de tweede en de vierde tel. Ook bij de ritmes van alle deelnemers lag het accent daarop. Drummers A en snares A uit Noord, speelden samen met West en deel van Zuid in triolen, met ook hier het accent op tel 2 en 4, en de rest van Noord en Zuid en heel Oost speelden voornamelijk alleen een noot op de tel. Geen enkele partij speelt iets echt ingewikkeld en al helemaal niets onspeelbaars, maar wanneer het allemaal tegelijk gespeeld wordt, samen met de twee bands op het podium is het toch één groot spektakelstuk. <5>

<1> zie de gehele video op Youtube: 2.000 DRUMMERS ON THE BEACH - FOUR HORIZONS (CONCERT VIDEO): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1O3xjhC9MHU (2018).

<2> Kijk op de website van 2000 drummers aan zee voor meer informatie over het evenement: https://www.2000drummersaanzee.nl/.

<3> De composities en instructievideo’s zijn hier te vinden: https://www.2000drummersaanzee.nl/compostie/.

<4> Homo Ludens van Johan Huizinga (1938)

<5> Zie hier het resultaat: https://youtu.be/1O3xjhC9MHU?t=2360

0 notes

Text

Druk op Alt-J om te spelen

Door Max van den Heuvel

Mijn ludo-muzikaal object betreft een filmpje van YouTube dat “how to write an Alt-J song” heet, geüpload door Fleece Music.<1> In het filmpje zijn twee jongens te zien die aan de hand van een loopstation een liedje maken, waarmee ze willen laten zien hoe je een liedje maakt in de stijl van de band Alt-J. Ze nemen fragmenten zang (en een beetje percussie) op met het loopstation en met teksten zoals “Butt, put it in my butt” en “Can you put it up inside, if you want to put it in my mind”. Dat het op de muzikale stijl van Alt-J lijkt, komt door de stapels van galmende zang over elkaar heen en een knijpende zangstem daar bovenop. Belangrijk is de ondertitel die het filmpje heeft: “THIS IS A PARODY…nothing mean spirited towards alt-J”.<2> Dit maakt duidelijk dat ze een geparodieerde versie van een Alt-J liedje proberen te maken, zonder enige serieuze bedoelingen. In deze post wil ik de spelelementen die in dit filmpje naar voren komen bestuderen, om aan te tonen dat dit filmpje beschouwd kan worden als een ludo-muzikaal object.

Allereerst is het nuttig om te kijken of dit filmpje past in de speltaxonomie van Caillois, die onderscheid maakt tussen verschillende soorten spel.<3> Dit komt erop neer dat hij een vierdeling heeft gemaakt op basis van competitie, kans, imitatie en duizeling, waarna een tweedeling toegepast kan worden binnen de categorie zelf, tussen vrij spel en structuur.<4> Het filmpje past goed in de categorie van imitatie, want de jongens zijn bezig met een parodie, ofwel nabootsing van Alt-J nummers. Ze nemen tijdelijk de rol aan van (een lid van) de band en doen alsof dit een nummer is dat Alt-J zelf geschreven kan hebben. Interessanter is de onderverdeling tussen vrij spel (paidia) en een structureel spel (ludus). Bij deze tweedeling komt het erop neer of het spel aan allerlei conventies vastzit (ludus) of dat improvisatie en zorgeloosheid voorop staan (paidia).<5> Voor de hand liggend lijkt de laatste hier van toepassing te zijn, omdat improvisatie en zorgeloosheid duidelijk naar voren komen in het filmpje. Terwijl ze muziek aan het maken zijn, eten ze lachend rijst wafels en voegen ze improviserend ideeën toe aan het nummer. Toch zitten ze vast aan een aantal regels. Ze kondigen namelijk aan dat dit de manier is om een alt-J nummer te maken, dus het eindresultaat moet daar dan ook daadwerkelijk naar klinken, anders schieten ze het doel van hun eigen filmpje voorbij. Ze zitten dus vast aan stijlkenmerken van nummers van Alt-J. Bovendien werken ze met een loopstation, waarmee ze ook vastzitten aan de regels die het loopstation met zich meebrengt.

Dit filmpje lijkt bij de tweedeling over regels in spellen ergens tussen de twee uitersten te schommelen. Om dit te verduidelijken, komt de theorie van Miguel Sicart over regels in een spel goed van pas. Sicart construeert de balans in spel tussen orde en chaos (Apollo en Dionysos), tussen de wil om te bouwen en te slopen in een spel, wat hij het carnivaleske karakter van spel noemt.<6> Deze balans maakt dat een speler zich aan de ene kant houdt aan de spelregels (om te bouwen), maar aan de andere kant zich daarvan losbreekt (om te slopen). Als het idee van slopen in iets bredere context geplaatst wordt en meer gezien wordt als het uittesten van de grenzen van het spel, is te verklaren waarom het filmpje van de twee jongens tussen ludus en paidia in schommelt. Om een gelijkende parodie van een Alt-J nummer te maken, moeten de regels in achting genomen worden en valt het spel in de categorie ludus. In dit geval is de ordelijke functie van spel in werking, om tot een gewenst resultaat te komen. Tegelijkertijd is de chaos functie ook in werking, omdat ze met een parodie de grenzen van het ordelijke spel aan het verkennen zijn. Door die grenzen te verkennen komt een parodie tot stand en is het vrije spel gelijktijdig actief.

Door het carnivaleske karakter van spel, wordt de balans tussen orde en chaos in stand gehouden.<7> Spel neemt namelijk deel aan de realiteit, maar houdt de realiteit tegelijkertijd ook op afstand.<8> Dit is wat Victor Turner een ‘liminality’ noemt: een tussenfase die zich losmaakt van alledaagse beperkingen, wat ruimte geeft voor deconstructie en reconstructie.<9> Turner gebruikt dit begrip voor het bestuderen van culturen, maar geeft ook aan dat het begrip ook in verband staat tot spel.<10> Dat spel zich in een tussenfase bevindt, komt aan de ene kant omdat elk spel in de realiteit moet plaatsvinden, maar aan de andere kant omdat het zijn eigen regels en context schept. Dit is te verduidelijken aan de hand van Huizinga’s idee over de speelruimte (de zogenaamde toovercirkel) die een spel oproept.<11> Huizinga verklaart dit als de ruimte die een spel oproept, die losstaat van plaats en tijd, waarmee het zich afscheidt van de werkelijkheid en zich onderscheidt van werk en bovendien zijn eigen regels heeft.<12> Hierdoor schept het zijn eigen context, maar blijft de context van de realiteit wel aanwezig, omdat een spel uiteindelijk altijd vanuit de echte wereld gespeeld wordt.

Deze toovercirkel is goed toe te passen op de Alt-J parodie, juist omdat het een parodie is. Het staat los van de werkelijkheid, het is immers geen Alt-J nummer, maar toch neemt het tijdelijk die rol op zich. Hierdoor schept het een eigen (spel)wereld, waarmee het zich losmaakt van alledaagse beperkingen. Ook dit verduidelijkt zich door middel van het concept van het carnivaleske karakter van spel. Sicart zegt hier het volgende over:

“Carnivalesque play takes control of the world and gives it to the players for them to explore, challenge, or subvert. It exists; it is part of the world it turns upside down. Through carnivalesque play, we express ourselves, taking over the world to laugh at it and make sense of it too.”<13>

De vergelijking van het carnivaleske karakter en een parodie komt hier duidelijk naar voren. Een parodie neemt ook een element van de ‘echte’ wereld en parodieert dit, met het doel om te lachen. Het carnivaleske karakter is dus goed te zien in het filmpje, waarbij de stijl van een bestaande band geparodieerd wordt, met als doel erom te kunnen lachen.

Terugkerend op de toovercirkel, is er ook nog eens een duidelijke scheiding tussen spel en werk te vinden. Van beroep zijn de jongens muzikanten, maar dit filmpje wordt niet beschouwd als onderdeel van hun werk. Dit komt misschien nog wel het beste naar voren door een reactie die Fleece Music onder hun eigen nummer hebben gezet: “NEW MUSIC COMING OUT APRIL 10TH!!! Pre-Save the single here:” waarna een link volgt naar een nummer dat ze officieel gaan uitbrengen. Doordat ze onder dit filmpje reclame maken voor hun ‘officiële’ muziek en dit nummer verder niet op die manier beschouwen, ontstaat een duidelijke scheiding tussen werk en spel.<14>

Wat maakt “how to write an Alt-J song” dan tot een ludo-muzikaal object? Ten eerste is het een muzikale uitvoering en past het goed in de speltaxonomie van Caillois. Spel en muziek komen dus samen in dit filmpje. Ten tweede is er een goed verband te leggen tussen het carnivaleske karakter van spel en deze uitvoering, mede omdat het een parodie betreft. Ook hiervoor geldt weer, het is een muzikale parodie, dus muziek en spel komen samen in dit object. Er zijn dermate genoeg spel elementen terug te vinden in dit filmpje, dat het gezien kan worden als een ludo-muzikaal object. Naast deze spel elementen zijn er ook andere factoren die bijdragen aan het ludo-muzikale. Voor verder onderzoek zou het interessant zijn om te kijken naar hoe de uitvoering (performance) en de context van het medium zich verhouden tot het speelse van het filmpje. De informele en onprofessionele houding en de huiskamerauthenticiteit lijken bij te dragen aan het speelse gevoel, dus dit lijkt me een goed startpunt.

<1>“how to write an Alt-J song”. Youtube video, 3:12. Geplaatst door: Fleece Music, 18 mei 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rlBskd3IaNw

<2> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rlBskd3IaNw

<3> Roger Caillois, Man, Play and Games (Illinois: Illinois University Press, 2001).

<4> Caillois, Man, Play and Games, 12-13.

<5> Caillois, Man Play and Games, 13.

<6> Miguel Sicart, “Play Is,” in Play Matters (Cambridge, MA; Londen: MIT Press, 2014), 9-10.

<7> Sicart, “Play Is,” 10.

<8> Sicart, “Play Is,” 10-11.

<9> Victor Turner, “Process, System, and Symbol: A New Anthropological Synthesis,” Daedalus 106, nr. 3 (1977), p. 68.

<10> Turner, “Process, System, and Symbol,” 68.

<11> Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: Proeve Eener Bepaling van Het Spel-Element Der Cultuur (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010): 26-27.

<12> Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 26-27.

<13> Sicart, “Play Is,” 4.

<14> Beargumenteerd kan worden dat het filmpje een ‘ulterior motive’ heeft dat werk gerelateerd is, namelijk dat van het verkopen van hun eigen muziek. Dit heeft alleen meer te maken met het gebruik van het medium waarop het filmpje is geplaatst, dan met het filmpje zelf. In het filmpje is geen verkoopelement te zien en de vraag is dan in hoeverre ze dit filmpje hebben gemaakt met een verkoopmotief in gedachte. Het zou wel een goede vraag zijn voor verder onderzoek.

0 notes

Text

Healing allies and damaging enemies: making music in League of Legends

How Sona relates to ludomusicology and performance

By Roos Mensink (6561365)

In the world of online games in which players choose a character with a specific skill set to represent them, game developers keep pushing the boundaries and coming up with exciting new playable characters that are based around a certain theme. In League of Legends, a five-against-five online multiplayer game, there is a total of 148 champions, each of them designed with distinguished abilities, backstories, and themes.

In this blog post, I will be taking a look at one champion in particular: Sona, maven of the strings. Sona is characterized by music. She plays a magical instrument called the etwahl, which looks like a traditional Japanese koto, but sounds more like a harp. While playing any champion in League, players can decide themselves whether they want to use an ability or not: it all depends on the situation a player is in. This means that, in theory, a Sona player could stay silent all game, or they could make music as they wish (as the game allows them to). Most of the decisions a player makes are based on the game, however, and not on making and enjoying music. So what makes playing Sona in League of Legends musical?

Sona has a diverse set of abilities. Her automatic attacks sound like single notes on a harp. She also has four abilities: “Hymn of valor” damages enemies. “Aria of perseverance” heals and shields allies. “Song of celerity” speeds up herself and allies, and her ultimate (“crescendo)” stuns all enemies in range. When one of these abilities is cast, a chord is audible. The chords match the abilities: a quick arpeggio signals speed, while a rich major chord signifies a safe haven.

To activate one of these abilities, the player has to press a button, after which the action happens. This is an example of Alexander Galloway’s concept of an expressive act: “These are actions such as select, pick, get, rotate, unlock, open, talk, examine, use, fire, attack, cast, apply, type, emote<1>.” Regarding Sona, the sounds are heard when she casts an ability or attacks. In Galloway’s matrix of types of game sounds, these would qualify as diegetic operator acts, which are actions initiated by the player that exist in the game world<2>. These sounds are also an example of Karen Collins’ kinesonic synchresis<3>. They are the result of a player action, like pressing a button or clicking a mouse. The immediate sound of Sona’s etwahl is the result of the player interacting with the game. In this case, Sona’s sounds could also be qualified as supradiegetic cues (sounds that exist in both the game world and the real world, usually directed to the player). The instant feedback reassures the player visually and audibly that the system works and it alerts other players that a certain ability has been cast.

There are different ways to define types of play. To do so, I am going to use the play taxonomy by Roger Caillois (explained by Roger Moseley), which first divides play into two categories: ludus and paidia. Paidia is centered around free play, whereas ludus has rules and values the player should follow. In each of the two categories, there are four more ways to divide types of play. These are agon (competition), mimicry (imagination), alea (chance) and ilinx (physiological effect)<4>.

When playing Sona, the player is engaging in ludus: there are rules about how Sona should be played and what items and other power-ups (such as runes and summoner spells) should be used on the champion. A player is also unable to cast an ability when they do not have enough resources (mana) or when the cooldown timer is still ticking after casting. However, there are always players pushing the boundaries. There are many interesting actions and interactions in this virtual arena, this magic circle. Some players literally go out of bounds. Others disregard the competition element for a while. With regards to Sona, players have actually taken the sounds she makes and remixed those sounds. In short, Sona-play (and any other champion-play in the game) can be classified as ludus play - but players will always test the limits in a paidia manner.

League of Legends is a competitive game where players fight against five enemies alongside four teammates. Sona will always be competing against other players, which clearly indicates the agon at play in the game. There is an option to play against NPCs, or to create a ‘custom game’, in which a player can try things out by themselves. The five-against-five online game mode, however, is by far the most popular. Other than agon, there are also significant elements of mimicry in the game. A player chooses Sona to represent themselves and to be her for a game.

People who are interested or experienced in music will probably be more likely to choose Sona as their champion, since they identify with her themes. Another reason players might choose this musical character, is because they want to identify with the themes: they want to see themselves as musical, even if they are not: “Identifying with a game character or role means to perceive oneself differently from a non-gaming situation, with one’s perceived attributes being more similar to the game character with which one identifies<5>.” So a person might not be musically gifted at all, but still wish to be. They could roleplay musical characters to fulfill that desire. Kiri Miller has found that people who play Guitar Hero feel like they have actually played music, even if they are not able to in real life: “Even though you haven’t actually put out the guitar riff, the game makes you feel like you have<6>.” This is the case, even if the performance is schizophonic, like with Sona. Her music is prerecorded and plays when the player hits just one button, which demonstrates the split between the sound and the source of the music<7>.

Identification with a videogame character is not surprising: as Alexander Galloway puts it shortly: “one plays a game<8>.” Galloway argues that there must be a kind of action in order to interact with a game. Otherwise, it would be a static object with rules and code<9>. This is also true for music instruments. A music instrument will not produce any sound if there is no interaction between player and object. The actual movement involved in games is pressing buttons and clicking with a mouse, which is not that different from pressing the keys on a piano or saxophone. In both cases, the person is a player, and the object needs some sort of action to work. This might result in players feeling close to Sona.

This mimicry entails performance as well. Every player chooses a character to perform and embody for one game. They can choose to play aggressive, defensive, or protective. Characters can also display certain ‘emotes’, optional actions like laughing or dancing. These emotes can be used to frustrate other players or to demonstrate skill - since it takes time to press these buttons, while the emotes themselves have no in-game use - or just as a humorous gesture. This is often done with champions who have a distinctive dancing animation or laugh (like Lux). During Sona’s taunt, she holds her etwahl like an electric guitar, and, as expected, we can hear an ironic electric chord. Using ironic obnoxious movements as a seemingly sweet, protective champion can add a comic counterpoint for players to enjoy.

In the end, Sona is a small part of the group of 148 champions in League of Legends. She is only part of the game approximately 2% of the time. Players choose Sona because they identify with her, or because they want to identify as being musical. Performance plays a big part in this ordeal: identity and musical performance and actual game performance. Playing Sona is more than healing allies and damaging enemies - it is associating yourself with a musical identity during the game and after.

<1> Galloway, Alexander R. Gaming : Essays On Algorithmic Culture. Minnesota: Minnesota University Press, 2006.

<2> Ibid.