Text

The Digital Promise and Pokémon Go

Photo credits: Times of Israel

Cultural anthropologist Rebecca Stein in her paper “GoPro Occupation: Networked Cameras, Israeli Military Rule, and the Digital Promise” explores the importance of photographic technologies within the political theater of Israeli military occupation form the perspective of Israeli actors. In particular, her paper focuses on the Israeli military growing investment in cameras as public relations tools, and on Israeli human rights groups’ employment of camera technologies against the military to make state violence visible. Stein’s study exposes the collapse of the digital promise of photographic technologies which could provide solutions to social and political ills along with greater image fidelity and speed of delivery, that is replaced by digital uncertainty. This promise breaks down in lapses. “Lapse” has two valences: 1) it marks the failure to deliver the promises of the digital 2) it marks a temporal interval attending the communicative operation despite the claims of “instant technologies”. Lapse performs as the counter-shot to the cyber utopianism which claims that digital media produces more evidence, democracy, and freedom of speech. The framework of Stein’s study is Israeli political theater of the last two decades within which the mainstream Jewish Israel public was losing interest in the occupation. This depended on both a strong Israeli economy and the separation barriers which enabled Israelis to live as if there was no occupation. Indeed, for most Israelis the military occupation and Palestinian experience under occupation were becoming harder to see behind ideological and material barriers.

The camera of both Israeli military and human rights organizations responded, in very different ways, to this political climate. As Stein highlights, the presence of many cameras in the Palestinian territories created a sense among international anti-occupation activists that the repressive terms of Israeli military had never been more visible and with greater proximity through their combat camera project. Yet at the same time, the terms of normative Israeli seeing were tempering this visual field, enhancing its inability to be seen as such. This conflictual visual regimes I think inform Mirzoeff’s idea of invisibility, for which even though the imagery of Israeli military occupation circulates around the public, it still remain invisible in exposing state violence and human rights violations. The events in the Gaza Strip in 2014 represent the large-scale military operation with combat cameras and what emerged was a language and practices to create a visual amplification which was required to counter-shot the imagery produced by the Gazan Palestinians. The need for the combat cameras and real-time PR image emerged from past Israeli failures in dealing with image making and circulation, in particular with the flotilla events in which 10 activists lost their lives by Israeli hands while they were trying to break Israel’s blockade in Gaza. The events represented a media disaster for the Israeli military since were delivered in a very slow speed to global publics. The Israeli NGO B’Tselem is the primary human rights organization concerned with state violence in occupied territories. Their challenge is to deliver an account of Israeli human rights abuses to an Israeli public tired of accounts of Israeli perpetrators and Palestinian victims. Therefore, Stein states, images require a frenetic verification and denunciation such as in the Bitunya killings in 2014. Two Palestinian youths were shot and killed by Israeli Border Police during a demonstration and, although it resembles many other episodes of Palestinian killings by Israeli military, in this case it was recorded by multiple cameras which; however, did not count as evidence of state violence. This suspicion by the Israeli public was translated in the forensic architecture’s reconstruction of the two killings in order to dispute digital evidence. The digital promise collapses in the perspective of a forensic architecture in place to prove digital evidence.

Photo credits: The Jerusalem Post

Postdoctoral researchers Fabio Cristiano and Emilio Distretti’s article “Along the Lines of the Occupation: Playing at diminished reality in East Jerusalem” explores augmented reality in relation to Pokémon Go considering its peculiarity of walking and exploration as the central features of the playing experience. However, the application of AR to gaming creates playable experience at the intersection between the real and the virtual worlds. However, in the context of disputed areas, object of conflicting narratives, augmented realties create hybrids that depend on how actual layers of space are transported into visual scenarios. Therefore, the visual world share the same characteristics of the actual world in order to construct the visual setting. In Pokémon Go the augmented reality results in the lines players walk in in order to catch and collect their Pokémons. The lines retrace actual streets and paths and by deferring the elements that characterize the city as divided it makes it seem as a united city instead of divided as it actually is. Cristiano and Distretti’s article aims at revealing the infrastructure produced by the intersection between virtual and actual world in a setting as the divided Jerusalem. It takes into consideration three important concepts: walking, line and void.

Walking represents both the essence of the game itself and for its epistemic value as a spatial practice. In the case of PG, it also represents the qualitative method of enquiry for the article.

Line is the object that describes the game reality being itself instrumental to the creation of urban space and informs the Jerusalem’s grid of borders, roads, checkpoints, and settlements.

Void is the image that embodies the detachment between real and virtual world In the game realization and erases the traces of occupation from its virtual representation.

Photo credits: Newsweek

The article shows the acts of playing PG in Jerusalem are removed from their potential of challenge and disruption. Following the Green Line, which divides the city of Jerusalem since the Armistice of 1949, it emerges a complex urban spatial order that functions overlapping visual and real layers of reality, while at the same time it keeps the borders that characterize the city invisible. Here there is the creation of a coexisting reality between virtual and physical.

0 notes

Text

Zeroing in, Overhead Images and Drones

Photo credits: The Conversation

Lisa Parks in the chapter “Zeroing In: Overhead Imagery, Infrastructure Ruins, and Datalands in Afghanistan and Iraq” describes overhead imagery and its circulation in global media culture. She starts the chapter with the metaphor of the zeroing in that signifies how viewers are positioned in relation to world events considering that they see the events from militarized aerial machines. To zero in means to aim directly at a target, as drones do.

Parks claims that overhead imagery has gained significance in media culture in four ways:

it has become the leading shot for events covered by news, and it is used to orient the viewer in its space of coverage.

it has increased the desire for their type of view counterpart, the close-up, which contrasts with its remote perspective

it has been used by mainstream media to attract the attention of as many viewers as possible

it serves as the symptom of the targeting practice of power – to conceive the world as a target is to conceive of it as an object to be destroyed.

Overhead images, according to Parks, represent parts of the world as sites of scrutiny, destruction, and extraction – one overhead image can reveal a site to monitor, to destroy, and/or to develop.

The first act of war to democratize authoritarian regime is the bombing of their communication infrastructure. This is particularly present in US’ bombing in Afghanistan and Iraq: US corporations invested in the telecommunication sector of both countries, then the US bombed the local broadcasting infrastructure while transitioning viewers from transmissions controlled by the old regime to a system controlled by US-led coalition.

Photo credits: The National Security Archive

The images of the sites widely circulated with arrows pointing to the target, and the act of guiding missiles to targets is transported with guiding acts of interpretation. The arrows are positioned to allow a quick and “efficient” read of the images, which Mirzoeff would call the “weaponized image” which is an image “developed as a carefully and precisely targeted tool”

Parks then discusses about the Shutter Control Rule which authorizes the US Government to shut down US commercial remote sensing operators in times of threat of national security such as in times of armed conflict. This rule ensures that the images depicting US military facilities and personnel locations will not be available to the general public by satellite operators. It raised various objections and the government did not officially claim to exercise shutter control. However, when the US government prepared to attack the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001 it paid to million per month for three or more of exclusive access to Ikonos satellite imagery of Afghanistan. By purchasing this access, according to Parks, the US government transformed the shutter control into a financial transaction, and denied news agencies to sue the federal government for violating the first amendment. When the exclusive license expired in 2002, the images became commercially available. In few years, Afghanistan became a digitalized land for anyone to navigate in Google Earth and had become datalands for sale. The Google Earthing of Afghanistan and Iraq is designed to boost the business potentials and profits of US companies as the satellite image has been used to both showcase the eradication of the Taliban and Hussein communication infrastructure and as a platform to imagine, design and map new ones.

At the conclusion of the chapter, Parks invites the reader to imagine a reverse shot for every satellite that would lead to a further investigation on the location, history and ownership of the satellite that gathered the image as a way of analyzing images and events.

Roger Stahl’s chapter “Drone Vision” offers an encompassing vision on drones in contemporary international arena. He claims that the drone has provoked debate regarding its use as a weapon, but with less attention to its role as a medium. Its visual dimension has extended its military utility to the realm of politics and culture. It is a tool to orient the Western subject’s relation to the state military complex. After 9/11 attack, the US’ deployment of drones divided itself into two programs: the first was the use by the defense department of drones in publicly declared zones while the second consisted of covert operations conducted by the CIA and Joint Special Operations command. During the Obama presidency drones were fired abundantly to the point, especially in the covert operation, that they became normalized and a signature of the presidency. The public debate was concerned with the ethics of long-distance weaponry but not with the policies guiding the use of the tool and the tool itself. The program violated both international and domestic law, it denied legal protections taken for granted for democratic countries, and it ignored the principle of distinction and claimed and astonishing amount of civilian life. The drone operations represents Giorgio Agamben’s concept of zones of indistinction that are the spatial manifestation of the state of exception. The condition of state of exception is an extraordinary circumstance in which the legal order is suspended, similar to a state of emergency, in which the state performs “legal” lawlessness.

Drones, as Stahl emphasizes, operate as projection of imperial power through the domination of the airspace of the targeted territory. He also raises the question on how this projection has received tacit public consent. The answer is located both in the peculiarity of drones that removes the body and makes appear the war riskless and also in how the drone vision has trained viewers to see.

0 notes

Text

Regarding the Pain of Others, Precariousness and Grievability of Life

Photo credits: The Guardian

American writer Susan Sontag in the second and third chapter of Regarding the Pain of Others, explores the concept of distant suffering and how, as spectators of violence and suffering experienced by others at distance, we deal with and perceive the visual representation of conflicts and calamities. Indeed, she opens the second chapter by highlighting that being spectators of calamities at distance is a quintessential modern experience, provided by journalism. Wars are now also living room sights and sounds – “if it bleeds, it leads” is an essential feature of the news domain, to which the response can be compassion, indignation, or approval.

She states that awareness of suffering that accumulates in a select number of wars happening elsewhere is something constructed by cameras that act as mediating tools. A photograph has only one language and is destined potentially for all. Therefore, the understanding of war among the people who have not experienced war is now a product of the impact that these images have. Something becomes real by being photographed to those following from a distance as news.

Sontag also notes the peculiarity of photographs since even though nonstop imagery such as television, movies, and streaming videos surround us, when it comes to remembering the photograph significantly provides memory freeze-frames, which basic unit is the single image. The photograph provides a quick way of apprehending something and a compact form for memorizing it. In this sense, shocking images become the point since images, as part of journalism, are expected to arrest attention and surprise. As the old advertising slogan of Paris Match, founded in 1949, had it: "The weight of words, the shock of photos." This represents and is part of a normality of a culture in which shock has become a leading stimulus of consumption and source of value. However, if in the previous century atrocity photographs were scarce, our modern ultra-familiar, ultra-celebrated image of agony and ruin is an unavoidable feature of our camera-mediated knowledge of war.

Moreover, in relation to the historical moment of World War I, Sontag points out that photographs had the advantage of uniting two contradictory features: inbuilt credentials of objectivity, and a necessarily present a point of view. They were a record of the real since a machine was doing the recording, and a personal testimony of the real since there is a specific point of view of a person who had been there to take the photos.

Whether the photograph is understood as a naïve object or the work of an experienced artificer, its meaning – and the viewer’s response – depends on how the picture is identified or misidentified in relation to the idea, the moment, the place, and the public. Therefore, the photographer’s intentions do not determine the meaning of the photograph, which will acquire its own meaning by the diverse communities that have use for it.

In the third chapter Sontag describes the human desire to see images of suffering and cruelties; nevertheless, without a moral charge attached to them. Just the provocation: can you look at this? There is the satisfaction of being able to look at the image without flinching. Sontag emphasizes that we are voyeurs of images of suffering, whether or not we mean to be. In each instance, the gruesome invites us to be either spectators or cowards, unable to look. Torment, a canonical subject in art, is often represented in painting as a spectacle, something being watched (or ignored) by other people.

Exploring the representation of suffering, Sontag considers the different interpretation of the works of photographers and artists. By convention the artists “make” drawings and paintings while photographers “take” photographs. However, photographs cannot be a transparency of something that happened since to photograph is to frame, which in turn is to exclude. A painting or drawing is judged a fake when it turns out not to be by the artist to whom it had been attributed. A photograph—or a filmed document available on television or the internet—is judged a fake when it turns out to be deceiving the viewer about the scene it purports to depict.

American philosopher and gender activist Judith Butler in her blog post “Precariousness and Grievability – When Is Life Grievable?” proposes a way to read emotions politically, providing a relational view of self-identity as bounded with other human beings. Defining what lives are grievable, what lives count, is a social political process. Butler states that one way of posing the question of who we are in times of war is by asking whose lives are considered valuable that are those who are mourned and grievable. Indeed, war divides the populations into those who are grievable and those who are not. An ungrievable life is one that cannot be mourned because it has never counted as life at all. The other feature, according to Butler, in defining life is precariousness. Life requires various social and economic conditions to be met in order to be sustained as a life. It implies living socially which in turn implies living in the hands of the other. There is a significant dependent connection between our lives and the lives of others, which do not necessarily translate itself in a relation of love and care but constitutes an obligation towards others. Furthermore, we coexist with precariousness from the day of birth, which means that it matters whether or not this infant survives, and its survival is dependent on a social network of hands. Precisely because a living being may die, it is necessary to care for that being so it may live.

The value of the life appears when the loss of that life would matter. Thus, grievability is a presupposition for the life that matters.

Photo credits: TIME

An example of the lives that are less grievable than others, and to which the world turned its back is of the about 800,000 people killed in the 100 days of the Rwandan genocide. the civil war in Rwanda represented a deeply rooted social stratification often expressed and manipulated through constructed identities of the two local groups, the Tutsi and the Hutu. The two groups had various conflicts based on political, economic, and social struggles which culminates in 1994 in which 800,000 ethnic Tutsi and politically moderate Hutu were killed in the name of cleansing the nation to which the world has not intervened making the genocide happen in front of its eyes.

Photo credits: TIME

0 notes

Text

Globalizing the Aesthetics of Violence and Terror

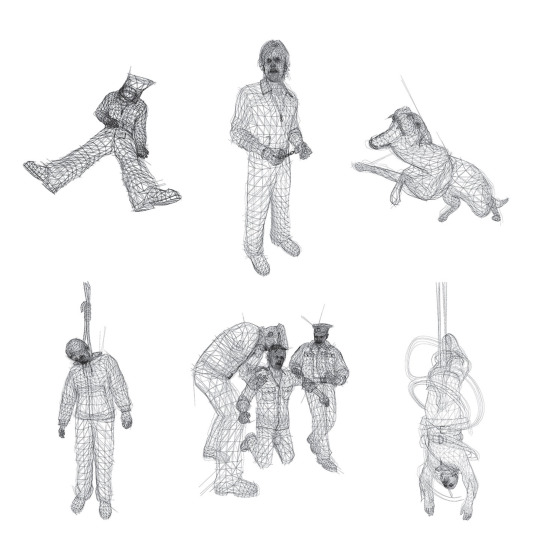

“Torture is globalized” is the sentence which opens sociologist Jonathan Luke Austin’s paper “Torture and Material-Semiotics of Violence Across Borders”. Austin in his work explores the morphologies of torture practices and how they have spread across time, space, and state-type.

The globalization of tortures is provided by fictional representations (film, tv, video games) which represent the ways in which torture travels and becomes available to a broader/global viewership. He provides an example of two descriptions: the first one is from a 2007 Red Cross report of a “prolonged stress standing position” procedure perpetrated by the United States to detainees and the second one is a 2014 United Nations report on the “pigeon torture” perpetrated by North Korea. Even though the names are different, the torture technique is identical, and this aspect informs the idea that there is a transnational convergence in the morphologies of torture. For morphologies Austin means the performance and the physical formats of torture which happen to be adopted in precisely the same way in two different geographical sites, across both US and North Korea’s national borders. Therefore, democratic states sometimes can be situated in the same space of violence as their autocratic counterparts. It is not possible to assume that there are innate differences in the origins of violent practices in correlation with the state-type – there is not a democratic-authoritarian binary which shapes a global space of violence.

Photo credits: NY Daily News

Austin’s mode of inquiry in his paper is based on the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) which sees social practices through the lens of material-semiotics (physical and representation domains) networks of relations between geographically distinct sites and constitutionally distinct entities, as well as human and nonhuman objects (cultural artifacts, technologies, and/not only human agents of war and torture). If human rights literature, the subdiscipline most concerned with torture, is concerned with norms against torture, material-semiotics mapping seeks to discern how a coexisting norm of torture is assembled across time, space, state-type, and world politics.

Describing the semiotics of torture, Austin provides the example of Jihad and Syria. Jihad was a low-level Syrian agent who used to censor newspapers before their distributions before being defected and fled to Beirut. At Beirut he described the brutality that he witnessed at a detention center. He describes the experiment with electricity, researching on the internet for more painful practices. They were always looking for more ways to make the game more painful. The use of the word game, which plays as a justification for torture, is not restricted to the Syrian context. Austin reports a US’ soldier description of a torture in Iraq, “… when they came in it was like a game. You know, how far could you make this guy go before he passes out or just collapses on you” (6).

The morphologies of torture are dependent on the circulation of norms of knowledge that cannot be restricted to delineable sociocultural space. There is not a unidirectional export of the knowledge of how to torture – there is not a policy transfer from an imperial nucleon to the peripheries, but rather, as Austin highlights, there is a (re) emergence and (re) convergence of violence and torture.

Photo credits:

Digital Mafia Talkies

Representation of violence and torture plays a crucial role in 1971 dystopian film A Clockwork Orange directed by Stanley Kubrick. Alex is a psychopathic delinquent who together with three individuals who followed him, the “droogs”, committed various crimes such as murder, rape and theft. He is sentenced to 14 years of imprisonment; however, in order to reduce his sentence, after two years of prison, he volunteers for an experimental therapy conducted by the government called the “Ludovico technique” which is supposed to rehabilitate criminals. The therapy consists in strapping the subject to a chair, clamping his eyes open and injecting him with drugs. Alex is forced to watch films portraying violence and rape and becomes nauseated to the films. However, as the film progresses, a series of events led Alex, after the allegedly successful rehabilitating therapy, into a hospital with multiple injuries after attempting suicide. At the end the viewer finds out that the experiment did not change Alex’s nature in regards of violence and sex.

Photo credits: Moviegique

The “Ludovico technique” resembles the “electroshock” therapy especially in the first years of its adoption in mental health treatments. Electroshock was used frequently to treat depression or hysteria usually with high levels of electricity and without anesthesia. They both are highly disruptive treatments attempting to make patients heal from their deviant status.

Photo credits: Psychology Today

0 notes

Text

Saw, Torture Porn and Video Surveillance

Photo credits: Cinematographe.it

“I want to play a game” is the iconic quote from the famous Saw, the first of a 7 films franchise, a 2004 horror movie directed by James Van. The serial killer Jigsaw carries out games which involve kidnapping of victims who are placed in a scenario in which they are forced to make intricate choices to solve an “enigma” in order to survive/save their beloved ones or otherwise die. These scenarios involve destructive torture instruments designed to provoke devastating pain and violence on the body. Behind the Jigsaw’s mask, there is the identity of John, a terminally-ill man, who chooses the victims based on their appreciation for life. All the victims of the games are people who are considered to be abusing their life or the life of others and the games serve as a way to teach the real value of life. The selected victim for this movie is a doctor, Lawrence, who has been unfaithful with his wife and uncaring towards his patients and founds himself with a stranger, Adam, locked inside with him that he is instructed to kill, or lead his wife and daughter die, in the setting of a dirty bathroom with a dead man at the center of the room.

Photo credits: Horror Italia 24

Catherine Zimmer in the first chapter of her book Surveillance Cinema explores the concepts of video surveillance, torture-porn and zones of indistinctions. Zimmer describes torture-porn films as engaging in explicitly systematic violence of torture scenarios and often including narrative reference to the ideological, economic, and social elements that constitute the torture as itself functioning within the logic of a broader system. Moreover, the incorporation of surveillance allow to consider the function of surveillance in the narrative formation of systematic and systemic violence. Torture and surveillance have systemic intersections, and the relations between different films highlights the relationship between violence and visibility that are key in the function of surveillance in contemporary horror cinema and politics.

Zimmer explores these connections through Giorgio Agamben’s notion of the “zones of indistinction” that is the manifestation of the state of exception. These films indicate a mode in which surveillance politicizes narrative by using narrative as a cinematic “zone of indistinction”. The majority of torture-porn films are American products and Zimmer emphasizes how, after the 9/11 attack, the American military actions which established the detention facility Guantanamo Bay and the abuses of Abu Ghraib, cannot posit Americans as the innocent objects of torture scenarios. The appearance of the economies, bodily experience, and technologies of torture can be seen in conjunction with the politics of torture of United States and the world. According to Zimmer, Saw introduces the cinematic narration of torture as a starting point for moral and ethical dilemmas, and each torture or death scene is framed by a consideration of fundamental values and a punishment that reflects the transgression. Furthermore, the characters are in some ways both guilty and innocent and the film incorporates themes embedded in contemporary politics such as the morality/efficacy of torture, definition of life, fundamentalist belief system, and bodily and psychological experiences of violence. Zimmer highlights the importance of the video surveillance apparatuses along with the way in which Saw formulates torture by introducing technological mediation and surveillance features into the rules of the games; the relationship between torture and surveillance constitutes torture as a function of surveillance. Video technology, in various parts of the film, functions as an organizational methodology (surveillance used to monitor the scene) intended to produce and control responses (used as representation incorporated into the torture scenario).

Photo credits: screenshot from the article

Jigsaw’s games are an exercise of biopower since they are designed to define who deserves to live. Agamben’s concept of “zones of indistinction” which produces the figure of the bare life that is a life without political and legal rights. Sovereign power in the modern form, according to Agamben, is the designation of the bare life and the production of zones of indistinction. Surveillance, in particular, operates as a zone of indistinction in the political discourse of security and terrorism and the increased normalization of the state of exception.

Saw’s torturous narrative logic parallels the manifestation of sovereign power through the biopolitical designation of bare life, and that Jigsaw’s games function as zones of indistinction through which he can manifest his victims as bare life (41).

Saw narrates torture as an ideological project that, nevertheless, operate in a highly political sphere. All the aspects of the narration of the film function as biopolitical technological tools to produce the bare life.

0 notes

Text

Virtuous War/Virtual Theory and the Simulation Triangle

Photo credits: MWI

James Der Derian, Director of the Centre for International Security at University of Sidney, in Chapter 17 of Critical Practices in International Theory, explores the concept of virtual war and how it becomes virtuous war.

The two terms, virtual and virtuous, share the same etymological origin and both originally carried a sense of virtue – qualities and notions of right conduct. But in a modern use, the two words carry different meanings: virtual refers to technological connotations and is morally neutral whereas virtuous refers to moral connotations and is technically neutral. In the context of war, virtual wars are characterized by usage of software over hardware, reliance on networks rather than on agents that move the events, easier mutation and adaptation, removal of violent aspects but of also empathy and moral connotations. Virtual wars drastically reduce the gap between reality, which represents a gray zone between virtuality and actuality, and actuality, which represents the traditional aspect of war conducted in the physical battlefield. Der Derian states that virtual and virtuous now can be rejoined by the efforts to effect ethical change through technological and military means and the United States is leading the way in this virtual revolution. US’ diplomatic and military policies, indeed, are increasingly based on technological and representational forms of discipline, deterrence and compellence that can be described as virtuous war that is the technical capability and the ethical imperative to threaten and, when necessary, actualize violence from a distance with no or minimal casualties. Moreover, virtuous war has the power to keep death out of sight creating the risk that one learns how to kill but not to take the responsibility of it and does not experience its tragic consequences. Virtuous war sanitizes violence by removing the body and the blood. It removes the human aspect of war and creates a detachment that destroys empathy.

The distance that is created by virtuous wars executed remotely is the principle of an experiment conducted by Wafaa Bilal, an Iraqi-American artist. Bilal spent one month in a small room with white walls and a minimalist design which was composed of a bed, a desk, a computer, a lamp and a paintball gun with a camera on it. The room was livestreamed on the internet, and anyone could look inside, and anyone could take control of the gun and shot. Bilal reported that he was shot at 70,000 time and received 80 million hits from 128 countries.

Photo credits: universes.art

He had this idea after watching an interview with an American soldier who, sitting in the United States, directed drones to fires missiles in the Iraqi desert. He emphasizes how he was shocked to see how the soldier was completely disconnected physically and emotionally from his actions that had tragic consequences in Iraqi. He says that the idea was to turn ordinary people into drone operators who could target someone far way, with the exception that they would not be following orders. They would have a choice whether to shoot, and Bilal’s suffering would be visible. Bilal wanted to connect with the people that there are real consequences to these actions.

In chapter 15 of Critical Practices in International Theory, Der Derian explores the concept of simulations and simulacra war. He opens up the chapter stating, “all but war is simulation”. Simulation can be defined as the reproduction of a real phenomenon that is transformed in an exercise and war places itself as the most virtualized and simulated event. War simulators try to make all the real coincide with their simulation models, but it is no longer a question of maps and territory since it has disappeared the difference between the simulators and abstraction. There is no longer a real that is being represented because the signs of the real have replaced the real. Therefore, the real will never again have the change to produce itself. The simulacrum is hyper-real sheltered from any distinction between the virtual and the real. Der Derian compares the simulacra of war to Disneyland quoting Jean Baudrillard, “The Disneyland Imaginary is neither true nor false; it is a deterrence machine set up in order to rejuvenate in reverse the fiction of the real.” Compared to Disneyworld, Der Derian states, the military and industry were open laptops on the role of simulations.

0 notes

Text

Necropolitics and the Becoming Black of the World

Photo credits: documenta 14

Cameroonian philosopher, political theorist, and public intellectual Achille Mbembe in his work Necropolitics explores the notion of state sovereignty and its role in deciding who lives and who dies. Indeed, Necropolitics concerns contemporary forms of subjugation of life to the power of death. Mbembe assumes that the ultimate expression of sovereignty resides in the power and capacity to decide who may live and who must die. Hence, to kill or to allow to live constitutes the limits of sovereignty (11). Moreover, Mbembe takes a distance from the traditional definitions of sovereignty found in political science, which locate sovereignty within the boundaries of the nation-state, within institutions empowered by the state, or within supranational institutions and networks. His account, instead, builds from French philosopher Michel Foucault’s concept of Biopower and Biopolitics. Biopower is defined as the domain of life over which power has taken control - the ways in which the state lawfully exercises power over the body. It is sovereignty exercised over the life, the extension of state power over the physical body of a population. For instance, a way in which the state can legally exercise its power over the body is through laws against euthanasia. By prohibiting the practice of ending life of a patient, the state limits the freedom of choice over the patient’s own body. Moreover, the state intentionally perpetuates the patient’s suffering since usually, patients who opt for assisted suicide, are terminally ill or experiencing persistent and debilitant pain and suffering. Therefore, making euthanasia illegal forces them to live a life they do not want to live in a never-ending pain.

Photo credits: Rappler

Biopolitics, therefore, is the governance exercised through biopower. When a state becomes the protector of the population’s life, everything that is recognized as a threat should be eradicated, which generates the state’s interventions with the mission of security for its own population or territory, claiming to act for the sake of safety. It is the state which decides that, in order to protect its own population, war becomes a necessary event in the name of the homeland (as it happened in the United States under the George W. Bush administration after the 9/11 attack). Mbembe also draws on Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s concept of state of exception, that is a condition in which the legal order is suspended, similar to a state of emergency, in extraordinary circumstances performing “legal” lawlessness. The most infamous example of the state of exception is the Nazi extermination camps widely interpreted as the central metaphor for sovereign and destructive violence and as the ultimate sign of the absolute power of the negative (12). The inhabitants of the death camps are reduced to bare life, that is a life without political and legal rights and becomes just a battle for survival.

Furthermore, it is important to address the modern understanding of sovereignty. Mbembe claims that late-modern political criticism has unfortunately privileged normative theories of democracy and has made the concept of reason one of the most important elements of the project of modernity. The ultimate expression of sovereignty is the production of general norms by a body (the demos) made up of free and equal men and women. It is on the basis of a distinction between reason and unreason (fantasy) that late-modern criticism has been able to articulate an idea of the political, the community, the subject and what the good life is all about. Therefore, reason is the truth of the subject and politics is the exercise of reason in the public sphere. The exercise of reason becomes the exercise of freedom, that is the essential element of individual autonomy. In this sense, the romance of sovereignty rests on the belief that the subject is the master and the controlling author of his or her own meaning. Sovereignty is therefore defined as a twofold process of self-institution and self-limitation (13).

Mbembe’s concern is not on the figures concerned with the struggle for autonomy but on the figure of sovereignty whose central project is the generalized instrumentalization of human existence and the material destruction of human bodies and populations (14).

He continues his analysis comparing the different conceptions on the question around death of Hegel and Bataille. While Hegel sees death as the pathway to a greater signification, to the truth, Bataille sees death as not connected to meaning. Death is rather connected to violence, a crucial element for exercising power, and the dissolution of the body and the self. For Bataille sovereignty is the refusal to accept the limits that the fear of death would have the subject respect. Since the natural domain of prohibitions includes death, sovereignty requires the strength to violate the prohibition against killing. Sovereignty is not connected to rationality but is, instead, connected to violence over the body and the right to kill (16).

Necropower is performed through different features:

• territorial fragmentations – settlements (like Palestine that is completely fragmented by Israeli military occupation).

• vertical sovereignty – occupation of airspace and surveillance

• creation of gated communities

• aerial warfare combined with “medieval” warfare (like in Syria)

• combination of military and technology (like in the Gulf War)

• extraction of natural resources

• exploitation of civilians

In the introduction of his book Critique of the Black Reason, Mbembe describes the concept of the “becoming black of the world”. He asserts that Europe is no longer the center of the world, and this represents a significant event and experience of precarity.

The black condition of systematic risks, experienced by Black slaves during early capitalism, have now become the norm for all subaltern humanity. The emergence of new imperial practices is then tied to the tendency to universalize the Black condition. Such practices borrow much from the logic of capture as from the colonial logic of occupation and extraction.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Endangered/Endangering and White Paranoia

Photo credits: Los Angeles Daily News

In March 1991, Rodney King, an African-American man, was stopped by the police after a high-speed chase and was brutally beaten. A witness, George Holliday, recorder the beating with an amateur camera. The King’s case is the first reported case of police brutality in the contemporary media sphere. It is the case in which the bystander witness with a mediating camera and the video circulates worldwide. Even though Holliday’s video was played in the trial and shows clear evidence of the savage beating against a black body from an exaggerated number of officers, the policemen were not found guilty. This verdict led to massive and disruptive riots in Los Angeles: six days of urban revolt and clashes with police and the army would leave 63 dead and more than 2000 demonstrators injured and during which approximately $1 billion worth of property was destroyed.

Photos credits: NPR

Now the question is, how is it possible that the policemen were found innocent if there is indisputable evidence of their violent actions recorded in a video?

American philosopher and gender activist Judith Butler in her work ‘Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia’, analyses this event through the lens of racial bias which radically transformed a supposedly clear evidence.

The defense lawyer for the police officers used King’s gesture of raising a hand as self-defense to assert that he was attacking the cops and the police was endangered. This interpretation does not derive from the fact that the video was ignored; instead, it was reproduced during the trial but within a racial saturated field of visibility, which made the jury consider the black person guilty despite the violence, structuring what can and cannot appear within the horizon of white perception. This represents a crisis in the certainty of what is visible informed by the white paranoia since to the jury, what appears to be a body brutally beaten, it is a body attacking the police. Indeed, the jury watched what their racially-biased mindset inclines them to see – white superiority that does not allow the reality of the video. Butler stresses that the visual representation of the black body being beaten by the policemen was taken up by that racist interpretative framework to construe King as the agent of violence, not into its victim. This is not the simple act of seeing, but the racial production of the visible and what it means to “see”. Indeed, the visual field is not neutral to the question of race; it is itself a racial formation, an episteme, hegemonic and forceful.

French philosopher Elsa Dorlin in the prologue of her book What a Body Can Do, constructing her concepts from Butler’s work, raises the question around the right to self-defense. In a world in which representation of violence acts as a central feature in visual culture, images never speak for themselves. While many citizens saw in the video evidence of police brutality, the lawyers during the trial were able to assert that there was no evidence of excessive use of force: the officers had made a “reasonable use” of violence.

By defending himself against police violence, King became indefensible. The more he defended himself, the more he was beaten, and the more he came to be perceived as an aggressor. Rodney King is recognized as an agent of violence, as a violent subject. Black men are always made responsible for this sort of violence: they are its cause and effect, its beginning and its end.

Moreover, Dorlin affirms that to attribute disqualifying violent action and an entirely negative power of action exclusively to social groups constituted as ‘at risk’ also serves an important function, since it prevents police violence from being perceived as an aggression. Since bodies that have been made into minorities represent a threat the agents of every possible violence, the violence that is continuously exerted on them, such as the one of the police, need never appear as the filthy violence that it is: it is secondary, protective, defensive, an always-already legitimate response or reaction.

Events of police brutality are unfortunately frequent and are part of a systemic racial bias imbedded in society. On April 11, 2021, in Brooklyn Center, Minneapolis a 20-year-old Black man, Daunte Wright, was shot to death by police officers.

Daunte Wright with his son. Photo credits: New York Times

After being pulled over for a traffic violation for expired certification tags, and then officers discovered that he had a warrant for his arrest. When the police tried to detain Wright, he tried to re-enter his car prompting a brief struggle with the officers. The event was recorded by a body camera which portrays an officer pointing a handgun at him and shouting “taser”. After the car pulls away the police officers shot Wright, the car traveled several blocks until it struck another vehicle. Daunte Wright was pronounced death at the scene. Hours after the video of the killing was released, protesters gathered outside the Brooklyn Center police station.

Photo credits: New York Times

0 notes

Text

The Invisible Empire

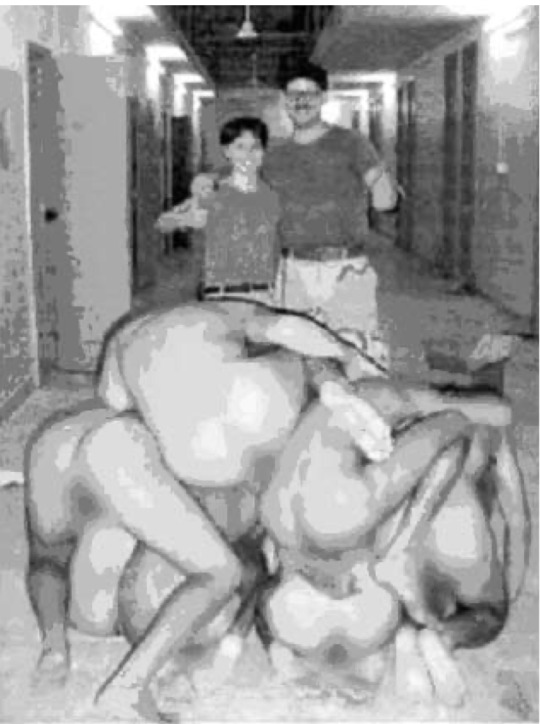

In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq officially to disarm Saddam Hussein of weapons of mass destruction, end his support for terrorism, and to free the Iraqi people. Nevertheless, a year later, in 2004 were released the photographs from Abu Ghraib, the prison held by the US, center of the interrogations. The photographs revealed the other side of the coin of the “liberating” mission of the United States, showing to the world evidence of the tortures and sexual abuses that the detainees experienced in Abu Ghraib. The photographs circulated around the world and had a huge amount of visibility; however, they remained invisible. Visual culture theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff in his work Invisible Empire: Visual Culture, Embodied Spectacle, and Abu Ghraib explores the reasons behind the invisibility of the Abu Ghraib scandal, the question of imperial masculinity and sodomy, and the relationship between the images and the US Army.

The question of invisibility revolves around the fact that even though these shocking images circulated around the globe, they did not convince Americans to take down the Bush administration; in fact, a few months later George W. Bush was re-elected. A similar pattern can be seen in regards of the question of immigration and the deaths in the sea during the journey migrants take to reach European shores. The real face of immigration can be represented by these photos which depict the suffering and desperation of migrants seeking asylum in a foreign country for safety and freedom.

Photo credits: CGLI Bologna

Photo credits: Vita

Photo credits: Agensir

Although these pictures circulate around the globe daily, populist political parties across Europe, that base their propaganda on an anti-immigration narrative, not only gain popularity but they usually occupy the leading seats in governments.

Moreover, of the about 2,000 photos taken in Abu Ghraib only 198 were released. Most of the pictures released portray male prisoners in acts of forced sodomy. This implies a careful selection and power in work to orient the gaze of the viewer, considering that images of abused women and children might have moved and shocked people more. Mirzoeff indeed states that for while the opponents of the war felt that the photographs from Abu Ghraib revealed its truth as torture and barbarism, its supporters could look at the photographs and recognize what was being done as the performance of the new imperial masculinity. Such masculinity is created by its negative differentiation with sodomy. In the Abu Ghraib photographs, sodomy was visualized as embodied spectacle, a mass of alterity that confirmed the long-standing sense of the “Oriental” as deviant. This relationship between imperial masculinity and sodomy leads to the creation of categories where sodomy is and can only be the property of the deviant “Other” (the non-Western). Sodomy serves as reinforce of heteronormativity and the notorious image of the pyramid of men depicts this relationship between the imperial masculinity and sodomy.

Photo credit: screenshot from the article

The presence in one photograph of Specialists Graner and England posing as a dating couple behind a sodomitical pile of prisoners is a trophy not of deviance, but of the assertion of the imperial body, necessarily straight and white, over the confused sodomitical mass of the embodied spectacle that is the object of empire (29).

It is important to emphasize that the official presentation of imperial torture as the application of sodomy to Islamic men by white men and women has a Western audience in mind, not Islamic or Iraqi. Within the United States, the representation of the Iraqi male as sodomitical and its images have been found repellent but not impeachable. It is a way to reaffirm white colonial supremacy and heteronormativity. The photos, which were not taken by chance but staged, were taken as a record of dominance of the soldiers over corporal space and time and were supposed for the consumption of the Army and its associates. Moreover, Mirzoeff claims that there is another mode of invisibility attached to these photographs: the very desire to see such violence enacted, recorded, and disseminated has become invisible and unsayable, even as it is everywhere in American culture. It is the invisible visibility of a police culture that claims that there is nothing to see while circulating its pixelated documents of imperial hierarchy around the Internet (30). There is a long history of violence, especially against the Other, in the American culture that however has never become a real issue or a cause for shame.

In this scenario sets the 2008 documentary Standard Operating Procedure, directed by Errol Morris. It is an investigation into the dynamics around the images of sexual abuse and humiliation taken by the US soldiers. It recollects the testimonies of soldiers and their justification for their behavior. The soldiers interviewed tell various stories behind the photos and the events concerning the prison, but they do not show regret for their actions. Notably Lynndie England, who compares in most of the photos, who was about 20 at that time and was in love and had a baby with Charles Graner, a staff sergeant, who directs the photographs. She states that she did what he suggested without questioning it.

The common element in the testimonies is “we just do what they want us to do”: they were just following orders. Indeed, the ordinary soldiers pay the highest price since many of them served time in prison. However, Morris expresses the systemic fallacy in the US army since no one above the rank of Staff Sergeant has served time in prison for the abuses of Abu Ghraib. Therefore, the ordinary soldiers serve as scapegoats to coverup the flaws of the higher steps of the pyramid.

0 notes

Text

Visual Culture and The War of Images

What is visuality? Visual culture theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff in his works An Introduction to Visual Culture and How to see the world: An introduction to images, from self-portraits to selfies, maps to movies, and more, explores the concept of visuality and its relationships and implications with conflict and power dynamics. Mirzoeff states that paradoxically visual culture can be everywhere and nowhere. It is everywhere since we are in a world saturated with images coming from different sources: from television, videogames, advertising, cinema, to contemporary art which are emphasized by the fact that we are surrounded by screens and various devices. Visual culture is nowhere considering that all mediatized representations are mixed.

Visual culture is concerned with sight (the physical capability in the domain of the empirical) when it becomes vision (the act of imagination in the domain of the psychological). However, Mirzoeff states, vision is not the terrain for visual culture until vision becomes visuality that is which renders the process of history visible to power. The visualizing of history is history by power that is the point of view from which the story is narrated. An example the same story but with two different points of view can be found comparing two photos from former President Trump’s inauguration day in 2017.

Photo credits: The Atlantic

This first photo is a bird view shot and is taken behind Trump’s shoulder and it intends to put the attention on the crowd attending the event representing the success of the Trump’s victory. This is the representation of the event from a specific point of view with the intent of demonstrating the high support that citizens have for their newly elected president.

Photo credits: The Atlantic

If we switch point of view, however, we can see a different perspective of the same event. This second photo portraits the crowd of the inauguration day from the street with the intent of putting the attention of the viewer on the many empty spaces, which narrates a different story when compared with the first one. Moreover, this image has been also compared with the photos taken at the same place, but completely crowded of people, at Obama’s inauguration day.

Indeed, visuality is a combination of the visual perceptions in the physical sphere and a set of relations investing information and imagination and involves an active world-making.

Visuality visualizes conflict and its primal form manifest itself since the colonial project in 1492, which is the base of a global society marked by violence and displacement. Modernity can be defined as the encounter between the “Natives” and the “Strangers” in a context of both expulsion and expropriation. The result of the interactions between the two is a double vision on colonialism: the one of the natives and the one of the colonizers. However, what becomes visuality is the only one of the two: the vision of power of the Strangers who destroyed the world of the Natives and imposed their own worldview.

Mirzoeff describes three fields where conflict and visuality manifest themselves:

• War where visuality is the viewpoint of the Hero/leader, as Napoleon for example, and his ability to create a mental picture of the battlefield.

• Religion and the long-lasting dispute of what should and should not be seen.

• Economy as Jonathan Beller puts is, “to look is to labor” since all looking in a commodity economy is work which results in attention economy in which value is created by attracting a person’s attention using algorithms that orient what and how the person sees in the world.

Visuality is constructed around three operations:

• naming, categorizing, and defining

• separating and segregating

• making this separation look normal and right

In the context of colonialism means calling the Natives as primitives, constructing the notion of the “Other” compared to the civilized West and making this separation look right claiming to civilize the natives to justify their actions of violence.

Mirzoeff emphasizes that we should claim the right to look, that is an exchange of looks in which all parties look in the pursuit of an understanding of the other. It is claiming political subjectivity and having the counter-perspective to visuality. “It is the claim to a history that is not told from the point of view of the police” (15).

Furthermore, Mirzoeff describes the period since 9/11, where the entire world became a place for possible conflict, as “the war of images” where images are used as weapons in the war of ideas to accomplish political goals and, in our digital era, the war of images changes the balances of power. The war of images is an asymmetric war in that partisans of each side feel themselves to be in the right and will not concede that the other side even has a case. In this scenario the US started a war of images soon adopted also by the other part, and in the image war it is important to show obscenity and violence in order to claim a victory.

Nevertheless, the obscenity of the image war was exposed when Abu Ghraib photographs of detainees held by the US in Iraq went public, revealing the atrocities and tortures inside of it. This photo made the “good” side of the war proposed by the West collapse.

Lastly, Mirzoeff analyses the use of drones in visual culture which, he states, optimize the new moment in global visual culture. Drones, networked devices, create a view from the air with low-quality images that are difficult to interpret but that are connected to missiles.

0 notes