Text

Wayco - Fall 2019

Wayco

for 2017

One: The Blur

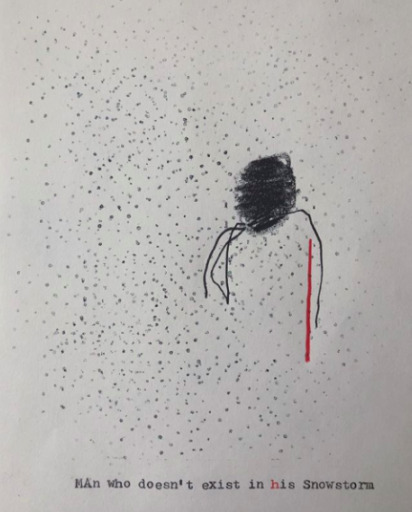

I awoke into myself. Rising from the hay-littered floor of the barn, I came to stand somewhere north of eight feet tall. I looked behind me, to the brown and empty stalls, then out the open door. My Companion was there. I saw a hat, then kerchief, long wool coat and spurs at the very bottom of them. They gave me one long moment to become accustomed to this state of things, then asked, “Are you ready?” I nodded and saddled the second horse just outside the barn, got on, and we rode silently into the white blur.

The snow between the barn and the first Stop blinded us and the horses and we were slow against its force of wind and cold. Is it cold here? Is it anything here? I’ve put my self aside and have made room for other things than self, than feeling, than memory. I don’t know who I am, but I know where I am. I am so tall but somehow I know that there is no one taller than me and that there is also no one shorter than me. I am neither male nor female and I have long, dirty hair but there is no way to clean it, there is no need to clean it, there is nothing here but seeing and giving and going forward.

The journey was less than half a mile but seemed to take a whole day. “A day”? I’m nowhere now, time isn’t in this place, and I am just a wet star flying frantically in a storm, a storm which has no direction, no direction, until it reaches the ground and eventually lands, part of something.

Finally, we got there, to a two-story shack with a main entrance up a set of rickety front stairs. My Companion hopped down, and began staying their horse, tying their reins to a metal hook fixed to the ground. They motioned to me to do the same. It took a moment, and then my Companion, the Other, asked again if I was ready, and when I said that I was, we moved toward the doors which opened into the ground, to the cellar, to the other worlds outside of this place.

We stepped down through the cellar door, into a girl high up in the air.

*

II: Wayco

I saw the text alerts on my phone while I was on their property, high up in the air. Wayco owned the air, like they owned the water and everything in between. The waiting area of their main offices was lush, and sunlight came in through the ceiling, where their might met the sky. David was with me, and he got the text, too. We were hitchhikers on this raft of luxury; economic nothings swept along with the elite. We were never meant to be here -- we weren’t like them. But we kept our mouths shut, always, always, because we had been initiated into the class of the living, those who would survive. The numbers -- were they a password? A -- I didn’t want to think it. I remembered briefly when an infantile Texan president pronounced nuclear ‘nucular’ and it was all anyone talked about for two years.

-- Codes. We had been given a code.

We had only been in this cabal for a short while, since Christian Shrekley, the new CEO of Wayco, fell in love with my Mother. He was young-ish, and somehow, so was she. She had raised me with the wisdoms of a thousand-year-old woman, but there she was, at the reception desk outside Shrekley’s office, dutifully organizing his business and staying silent, always silent, now, and beautiful and captivating, an endless font of what this man had, apparently, always wanted. The other handful of Wayco higher-ups standing there didn’t notice us much; we were just two unkempt writers whose names no one knew. But maybe it would pay off to know each other -- to really know each other. Maybe we were… in this together, circumstantial as it may be.

We were gathered in the penthouse office suite of Wayco headquarters waiting for news about the trip. The destination was a secret, and maybe the place we were all heading to never had a name. Maybe only Shrekley knew its name. Or maybe no one ever knew its name, this place we were going because it was beautiful and isolated and untainted by the hands of those hordes that Wayco needed, those hands which it exploited. There were fifteen of us, thirty hands. Just thirty hands.

The cars arrived, downstairs, and we all took swift, uncrowded elevators to the ground floor, and David and I got in the backseat of one of the black town cars driven by a silent and anonymous man to the site where the helicopters would pick us up. The Wayco app badge popped up on my phone screen, with a prompt to play a game. I opened it, and David opened the notification on his screen, too. We each saw a series of questions which we both got wrong, the answers of which were all related to intimate details of the Wayco group’s lives. “What was the name of Sam Priestly’s childhood cat?”

Silver

Noise

Sherriff

Alfonse

To each answer David and I got wrong, the app would respond with a brief summary of the answer’s context and relevance. “When Mr. Priestly was four years old, he was given a grey domestic longhair cat, whom he named Silver. Silver once scratched Mr. Priestly on the face when he pulled her tail, and for a brief period in the early 1960s, Mrs. Priestly and the household staff were concerned that Sam might be allergic to Silver, although the allergic reaction was concluded to be caused instead by raspberries. Silver lived to the age of seventeen, when she died of kidney failure, and is buried on the eastern Priestly estate in Darien, Connecticut.” A few questions in, David and I looked at each other, shocked but apprehensive about ever letting the rest of the group know that it had shocked us.

“What does David call Emily’s Panache sports bra?”

Bust strap

Chest binder

Tit prison

Punishment

We looked at it on each of our phones for a moment, then he clicked his screen off and put his phone away, looking straight ahead through the windshield of the car. I answered the question, and my screen exploded with celebratory confetti and balloons. I felt my face drop and become hollow, as I watched our autonomy get sucked up by Shrekley and Wayco and this conspiratorial, self-obsessed exclusivity of the upper material echelon. What didn’t they know? Where do we end and they begin? We can’t trust them -- but to what end? Are we safe? The American people aren’t safe, but… are we, just us, are we safe? Is destruction the very cost of our own safety? I pocketed my phone and looked straight ahead, too, although that pointed my gaze straight at the back of the driver’s headrest, and I tried to ignore my own sense of presence and the nauseating smell of leather, and instead feel small, invisible, undetectable in this world, and therefore safe.

Shortly, we arrived at the open field where several helicopters awaited us, and David and I boarded one with a few others, who were all in good spirits and friendly toward us, making only the slightest of jabs at our status and appearance, at first. Enough of that and they were soon riffing on the disparity between us and them, giving us advice on taking our CUNY educations with a grain of salt and, yes, citing the various health risks and benefits each associated with black and white truffles, and also mocking Chick-Fil-A, although Dan Westcott, seated across from us in the helicopter, owned 42% of it. Just because it was the two of us who were there. We smiled tightly and nodded, and we tried to enjoy the humbling view from our seats, both wishing we could turn off the receivers of our headsets to make these men just shut up. But things weren’t safe here. We couldn’t ignore anything. We were with wolves.

III: Enya

The headsets in the helicopter were apparently crucial, though. We rose higher and higher, beyond the altitude I thought helicopters could reach. Once above a threshold of sanity and realism, a widget inside the helmet extended to my forehead, and I felt a knock to my head backwards while my mind shot forward, stretching like the mind does. Like reaching, elastic, through sleep, I could see colors and movement but more immediately, I could feel them pulling on me, asking of me things I only knew how to give on a visceral level but could not explain. It was bright and blue and clear as I scaled a cliff, risked to the fall and unsure but unafraid, myself and yet eight years old and knowing myself to be eight years old but I was outside myself, watching myself watch myself watch myself scale the cliff and

I reach the top —

Enya - orinoco flow

sail away, sail away, sail away

— this is how I know my Mother. She dances towards me at great height and does not entirely know that I am there. She is billowed in white silk and gauze dress and shawl and the parts of her that know that I am there are happy that I am there. This is how I know my Mother. She dances toward me at great height looking at the sky and drinking it with a wide smile which does not know that I am there. She strides in a cloud and moves forward towards the sun, which is near her. This is how I know my Mother.

*

David and I found ourselves deposited on the precipice of a waterfall, perched on smooth stones just large enough to sit on, with a half-inch of water glistening through our toes over the edge, which was close but not a danger and all that I knew for sure was that we were high up, we were incredibly high up, we were as high up as anyone can be. We had been placed on these stones, our bodies placed here after the helicopter headsets had placed us somewhere in a different arrangement of body and mind. We were placed here without incident among the rest of the Wayco group, and on stones which were not being used as seats, grassy, light white wine in temperature-controlled, stemless crystal sat waiting to be drunk. I took a look around at men with absurd, terrifying smiles and haughty, impossible hairlines as they enjoyed the waterfall, the being-at of the waterfall, the being-high of themselves. I looked down and wanted to fill one of the glasses with the sharp, clear water being purified every second by the minerals of clean rocks higher than mountains and to drink it, and to be pure, too.

I tried to get David’s attention to ask him quietly what the headset had put in his mind, what he saw while we were out, but in his shy terror we couldn’t get the words out, and then Shrekley was addressing us, standing with bare feet in the cool, clear water and hiding his pride by tucking his chin to his chest as he smiled so wide that it was vulgar and uncanny. Then he raised his glass and announced that he and my Mother were to be wed. My Mother rose from the stone she’d been sitting on and her white billowed cloud of a dress dragged through the water, catching the cleanest molecules of shining moisture as she strode through the now-rising Wayco men to join her groom at the head of the group raising their glasses, looking, I knew, only towards the self. She shyly smiled in terror at the cohort, resigned to this survival, and this is how I know my Mother.

*

Among wolves, I shrunk from the sinful things that they said and did and I listened to Enya to repent. So did my Mother. We had been given a code.

*

IV: The D train

The blast had knocked me out, back in my life on the ground. I awoke after the impact underneath 145th street, and I recognized the yellow structural pillars but had no memory of where I’d been going to go on the D train when It had happened. At first fearful of the surface of the earth and what concentrated power had done to the air, I dove deeper, vaulting over the turnstile and hurtling myself towards the stairs down to the platform, to verify with the world I knew best just what had been done, and what had been undone.

On the D train platform, there were bodies everywhere. They were draped on benches, strewn on the floor, some even hanging, from inanimate hands, on poles in the still cars of a D parked with open doors on the tracks. The blast had been designed meticulously, and it had found these people under the ground, gotten inside them, ended them. I tried to remember when it was I had been saved.

The world around me was so still, but after wandering through that stillness for a minute, I spotted movement by the stairs leading back up to the air. I ran over to find a grizzled man splayed over several steps, making faint sounds with closed eyes and a twitching hand on a cane. He had stiff, short whiskers and a battle face, deep brown skin with riverbeds of wrinkles and valleys -- memories of a world which had just now ended, but breath in him still, breath reaching into this next stretch.

I knelt down and put my hands to his shoulders, asked him what he had seen. If he had seen anything. Where it came from. Does he know where he is. Does he know how he survived. Does he know. He roused and got his eyes open, realized he was looking at a survivor, and gripped both of my arms. Once I’d pulled him to sit upright, he shook me off and held his face in his hands, shaking it slowly back and forth, and he prayed to his lord. I faced the top of the stairs and began a quick, careful ascent.

*

I walked through the streets to find a living people so sparse and confused that we were, for the first time, independent from each other. Harlem, like the rest of this city, may have allowed for anonymity before the blast but now, the living looked around and were alone, really, cut off from anything they’d known and reaching for something that wasn’t there. That would never be there again. That never was there to begin with. A connection between us that could have provided the infrastructure to survive each other. To survive ourselves.

I didn’t walk north to my home. Home would have been a retreat further inside a self than I could bear to go. Instead, I walked south to Wayco, a people I was of not by way of similarity but through a convoluted perversion of the real, a departure from anything solid or trustworthy, a minefield of impossibilities. I walked through neighborhoods which stirred only slightly with movement from bodies wondering how to put to use anything they’d been taught. This was not an antagonistic end to the world; it was a somber and remorseful pause after a long reign, a moment in which the loudest voices were the ones from wind. From the silences of knowledge. We knew more than we had ever wanted to admit.

I got downtown to the fully operational glass tower and rode up in a panic. Now that Wayco had gone through with it, would I be able to face them without shaking, revealing my disgust at their strategy towards this success of finality? Can I hide among wolves, now that they’re this covered in blood? Or am I covered in it, too? I looked down at my trembling hands, balled them into fists, gritted my teeth, then took and released a deep breath, released the grip I had on my whole self. I was not who I thought I was.

The elevator opened and it was David I saw first; he had come from closer, had come right away. He had known to come. He was facing the elevator doors in wait, and when he saw me, he covered me with his arms, his face. He started some sentences but didn’t finish any, and once we had established ourselves to each other in this space, we looked to my Mother.

She stood with a grinning Shrekley surrounded by the eleven others clapping their hands to each other’s backs and clinking glasses of scotch. She and he at the center; David and I off to the side. This was how I knew our survival. The lot of them, Shrekley and the eleven other closest, they were celebrating the success of a plan that had been a long time coming. The destruction of man, leaving these men safe, high up in the air.

My Mother slunk away from Shrekley towards us while he laughed with Allan Sinclair, whose industry had been media, and they were laughing about the incomprehensibility of the Population Control Blast being seen as a race or class issue, as it had been treated by the critics of Wayco’s terrifying ideology, an ethos which had hidden in the places where we had lived our lives. This skepticism was a conversation which had only ever existed in the far reaches of the internet and fringe documentaries. Allan chuckled at the most popular proletarian conception that an event like this one, with a survival rate of one in eight and with Wayco survival guaranteed, wasn’t for everyone’s good. The same things I’d been hearing. I looked to my Mother and she slowly poured her own drink, vodka over ice with raspberries. She stared intently at the berries as she muddled them and then she toasted, low, to just David and I, and while we had no drinks to raise we met her eye to hear what she had to praise. With a few sparkling tears welling, she whispered to us a prayer for sailing away. To sailing away into this incredibly empty expanse, a chant to trust nothing but vulnerability as we made our way through all of the space we now had, all of the unknown at our disposal. She shrugged tightly as she said it, and refused to drop the tears, then downed her drink, and turned her back to us and faced the We of Wayco.

“We did it,” I Thought. I knew who We were. I knew who I was.

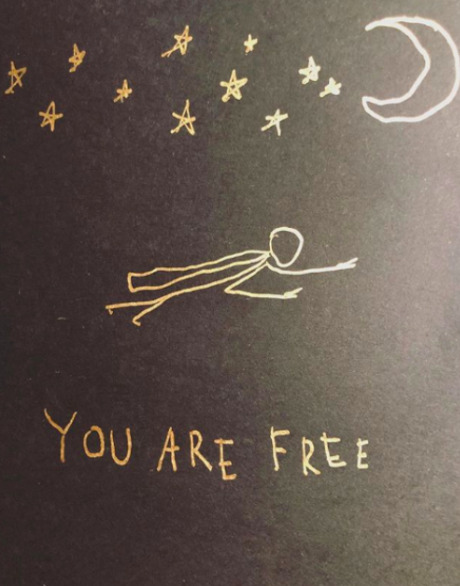

Five: The Other

I found myself rising from the girl high up in the air into the cellar below the snowy ground in this place outside of space, outside of time, where I was tasked with understanding -- with only understanding -- that which can’t be Named or Faced. With seeing what was preserved for sanctity in this long, winding Thing that had no option but to Be.

The Other was standing with their hands on their knees, feet spread to ground them on the dirt and sawdust floor of the cellar beneath the Stop. I had been chosen, after death, to study the memories and the fears of the one, the all-one, the history of the world, whose name is Duke or god or Gaia, because he needed to heal and he needed to not be alone. I was being led into my position by another selected angel, this Other, and would in turn lead the next Chosen to do the same, to learn how to heal him. We would watch the world pull back in quiet moments and we would watch it burn, to see what he could see, what only he could see. We would help. He would be whole. This place is the only place we are apart from him, and once he has been joined, we would be whole.

The Other and I both stood in the cellar in our own exhausted ways, possibly parted in disparate reads of Wayco. I knew the all-one to be a Mother, to be fallible, and in such, to be resigned to fallibility itself and to the real. Horrors bear as much weight as the mundane, but the world was heavy with experiences, and ideas of what could be, looking inwards on the real through its own faceted specters. I breathed a sigh of relief that he was who I knew him to be, that he was, here, what he’d shown himself to me to be. Reverent, himself. Trapped and trying. Committed to feeling through -- willing to invest in -- just about anything.

My Companion gagged. I stepped back and they pulled out of their mouth a long, thick, golden hair, and at the end of it, a wet lump of black guts. They gasped and choked as they looked to me, and to the lump on the floor of the cellar illuminated by the light filtered white by the snow coming in through the open door above, then back to me. After a moment of struggling to breathe, they said, “thanggud. I needed that.” I stood back in my admiration of catharsis, of the work being done. god wasn’t here in this place; I couldn’t look for him in the ways that I had, in life. He needed to be alone. Unlike all of the times we needed him, here we let him be, and so instead, I steadied my own self in this Lack and pulled myself up to my full height, and my Companion and I both faced the stairs up to the snow, the horses, and the air up there where air was not, where nothing is, in this place where only dreams metastasized.

We returned to the horses, loosed them from the ground, and looked to each other a final time. The Other nodded goodbye, then rode past the shack on into the white blur and I, through the blur back to the barn. I was ready, and now it had begun.

***

0 notes

Text

Of Your Life - Fall 2019

Of Your Life

Adapted from Pavement’s “Shady Lane/J Vs. S” from their 1997 album Brighten the Corners

Actually, eating anything at this point might do too much damage. There’s the ulcer and the bloating, two completely separate issues presenting a relentless challenge across their respective territories in my body. I’m walking the line between showing them my body and hiding my body from them and they already know that’s what I do, so my stomach is both there and not there depending on how endeared they are to my prerogatives. If I grab something -- anything -- the bloat will find its way to the shrouded beast, and if I don’t, I’ll be unable to speak or breathe or move comfortably because of the acid shooting up the tubes in the hearth of my body as the world sees my body. The breasts, the face, the front of me at eye level. Underneath those things, a raucous party. No one was invited but it’s not dying down.

I used to be pure.

But I have Tums and they’ll have coffee set up so I’ll sneak a splash of liquid dairy pretending not to be a freak and it’ll quiet down. Maybe the discomfort has come to be too close to a home, comfort itself, for me to eviscerate it so thoughtlessly; maybe this burn, these nerves, maybe this is where I live.

I’m here.

I sign in for the doorman and the time stamp is eleven minutes earlier than I had needed to be here. The elevator is both fast and nice and so I hope no one else gets on, because they would look me up and down and wonder if I’m homeless since I don’t know how to dress for SoHo and if I did know how to dress for SoHo I might still refuse to do it. But I remain alone because the elevator is fast and as I step out I wonder if I would even want the elevator at home to be so nice, or if I need things to be ugly and faulty to be at ease after all these years in earnest spaces.

I don’t struggle; I withdraw.

On the eighth floor, I get to a bathroom, Tums, a little setting powder (these lies I tell myself). I check my hair. It’s so sad but they already know that’s how it is and so my ugly hair, my ugly hair is fine and so, and so I follow the signs through the labyrinthine hallway all taped a bit cockeyed to the walls until I see the final “CASTING” on the door, and I open the door, and I walk through the door, and I’m in the door, and I’m here.

I don’t know when to photograph my life; too much seems momentous or too little.

There are three grey couches along the walls of the sunlit waiting room and two gunmetal sculptures of ovals approximating people, one in the middle of the room and one in the corner between two of the couches. I sign in without a word or even much of a glance at the thin brunette in her affected and prematurely exhausted importance sitting behind the desk set back from the wait and I take a seat closest to her. Do they know I love authority, any authority? I’m thinking about who might have been in this room earlier today, yesterday, tomorrow, and how close this production is getting to the truth and Ray flashes through my mind, Rafa, Holland and Anita, Tony. I picture their typecasts filling the room, a bunch of surly, balding brown bears filling the couches or maybe eight year olds with impossibly long twin braids; every one-legged mom-aged actor in the tri-state area. I’m thinking, I’m thinking about how close these casting directors are getting to the people who have populated my life and then I’m thinking, then I’m thinking about how close the people who have populated my life have been to me. There are distances, probably, that are getting close-ups in this thing. I picture a Sarah K. type filling this room, blonde crowns bent over magazines, and even though I am grown now, intimidation sets in as I envy the size they’d all be, their grooming, the way none of their nails are misshapen and all ten of them fit cohesively on the ends of unchewed fingers. I fail to sink into myself as I remember how Sarah seemed to hijack the backwards allure of my glasses, appropriating it onto the health and blasé wealth of Central Park West, and how her simple hair always did what she wanted it to do, which was nothing but shine. And I snap back into the room and into myself when it finally strikes me as absurd that I’m the one who would pretend to not be obsessed with these girls, these actors who want to be cast as Sarah as much as I want to be cast as anyone, anyone, in my life.

I am of these tiny little uses.

I am myself so I pull out something productive -- I highlight Michael Pollan. It’s about cattle. I remember the potential for dairy to quiet my insides and I take a look around. It’s skim milk next to the coffee machine, which doesn’t help me much. I think, you’d think they’d know, but at least the cups are biodegradable.

Sometimes I am on fire.

I’m reading, yeah, sure, I’m reading this section where he could get elitist but doesn’t, but I’m zoning out and I’m thinking about how the conversation with my agent later today is going to go. I know when I plan these future conversations it belittles the actual because it doesn’t matter where I go, I don’t know beforehand that for some reason I’m going to bring up Vermont, or O Brother Where Art Thou, or how rum cures colds. The actual is only vaguely predictable and I attach myself to its precursor, imagination. If it were up to me I’d stick to the fake talks and get fed through a tube, because the world I can touch is disappointing 73% of the time, I found recently, but what I stand before is a casting call I was born for and if I didn’t show up to this audition in front of these real people before retreating again to my apartment lit only by small lamps, never overhead lights, I’d kick myself for losing out on material to tell people when I imagine that I’m having conversations with them.

Reflection, self-fetish, auto-fetish, meta-fetish, reflection.

A door past the desk to my left opens and I immediately make an effort to slow my heart rate. There’s a put-together woman with a ponytail and a premium tee shirt holding a clipboard standing in the doorway and she looks at her clipboard and then up and she says my name with a question mark at the end and I nod and she turns for me to follow her. I pick up my tote bag and reflexively continue the movement to awkwardly smooth my skirt over my thighs and just hope that if she is paying attention she’s already gotten the note about the strange way that I design my outfits and also that she excuses me for the sight of my legs, and finally that she won’t ask me to bend over for anything. I think they know, I think. They have to know.

In truth, I can handle anything.

So now I’m in a bright room, a bright room with mirrored walls and there are four people at the folding table facing a lone chair. None of them have ever met me, not even Mr. Moody, who should have met me. I access cheer and introduce myself and second from the left at the table, a Mr. Clean type, he ignores me to lean over and asks Ponytail, “Is this the…” and she tells him yes without looking at me, and once they’ve all heard that they look up from their papers and each other to face me and with a regulation boredom Mr. Clean says, “Hey, great to meet you. So did…” he scans my resume for Bernard’s name and continues, “Bernard tell you what you’re up for here?” I nod yes as I sit. Mr. Clean tells me with a reference in absentium to comedy, “No small roles, right? So in this scene we have the, uh, the…” he looks around and goes for it, “the you-character, you know, she’s doing pretty well right now, she’s this stellar student and she’s kind of leaving that, uh, that stuff from ’08 and ’09 behind, you know, she barely remembers that, and then Howard--” Ponytail cuts in, “Your dad,” she says and I nod that I have absorbed that it is accurate that my father’s name is Howard and Mr. Clean says, “Right, your dad, he’s like wracked with worry about you all the time still because he, well, you know what, actually, how would you say this, yourself?”

I have been more than lucky.

“Oh, thanks so much for asking,” I breathe out in what is almost a laugh, and maybe I flush a little, and I bring my hand to that hearth of my cleavage, which is a not entirely unsurreptitious display of modesty. “Um, I guess he was just really at a loss about what to do with such a sick kid, when he’d insisted for so long that nothing was wrong, and maybe avoiding the idea that I might, um, traipse into his territory with the… the death-drugs,” I cast my eyes around in apology for the uncouth mention of dirt in this room and they first land on Ponytail, whose eyes are on her phone screen, and then on Mr. Clean, who’s leaning back with his hand to his chin and he nods and motions for me to get to the point and so I continue, “Actually, I don’t know if this is useful for you but he -- he told me the other day that he hadn’t ever known that I had done that much cocaine in ’07, so he was always sort of --” I’m cut off by the tall, severe woman in what could easily be men’s clothes to the left of Mr. Clean, and her mid-Atlantic accent adds to the Tilda Swinton vibe when she says, “Actually, that doesn’t help us and it might be best if we just, erm… stay away from that sort of, er, retroactive speculation with new information. I mean, it’s not like this is a, a vanity project, dear.” All four of them laugh.

I am an island like you are an island and you are an island.

Mr. Moody, bald black pate hedged by grey fuzz, shuffles some papers and doesn’t look at me but gives me the relief of saying, “Okay, so he’s clearly got a different approach to all this than Rose, sort of out of touch with the reality of it. And what we have in this scene is that he’s walking on, what is it, 9th street, and he sees Margaret, the doppelganger.” Moody is focused, looking up at me now and he sees past my invalidity the most of the four, he sees me in front of him and I’m more or less like everyone else in my determination to keep moving and he knows that, and he knows. “So she’s just standing there on the corner, and he sees her and he thinks you’re ignoring him and he gets in her face and shouts at her but it takes him… what, about a full minute or so for him to really process that it’s not you. He thinks it’s you and that you’re out of it, but it’s him that’s unhinged here… and it’s sort of everybody’s own cross to bear, the negotiation of you coming back to reality and just really being here finally like everyone, and also their understanding of what it is to have been here in reality in the first place, while you were gone.”

It’s not my movement that’s looked to, but where I land.

The other three have been looking at Moody and nodding as he says this but then Ponytail faces me and she asks if I can answer some questions about 2011. She says it’s to test the waters of how accurate we can make the scene to Howard’s perception, and she makes a joke about being old, about how long ago 2011 was, but I’m breathing low in my body just like I have in all moments and 2011 is still happening, and it is happening, and it is, and in my insistent consistency, it’s reliable and can’t be stopped.

Time is everybody’s.

I say sure and first she asks me, “Did you look at your passing reflection in windows?” “No,” I say. “Did you smoke?” “Uh… yes, yes I did.” “Were you in love?” “No.” This gives her pause and she looks at Moody and then at Tilda and Tilda leans forward and asks, “What sacrifices did you make that year?”

I had given everything I had, already.

I wonder for a noticeable amount of time what it was that my dad saw that day, that I had, in their words, sacrificed, that was somehow also palpable in Margaret. I stop myself, though. What did I sacrifice in 2011? I haven’t worked in so long and I need this part so fucking bad. But then I think of myself and my success at being in broad strokes and this is different from considering what answer they want because this is one of those times I honor the actual instead of the movement that I hope for and maybe that’s why they’re here, maybe this whole thing is an honorific, it’s the ways I am somehow so good at being. This is how I look when I’m honest. Slowly I say, “I started to lose pride. It took a few years to gain anything from that.” And all four of them immediately look down to the table to write a note on whatever paper is in front of them but while they’re still writing I realize how to get the part and instead of being good at being I say, “You could see it in my… in my spine.”

There has never been solitude; manifestation is endlessly dependent.

Now they’ve all looked back up at me again and no one says anything for a minute. Then I ask, “Would you like me to uh -- did you want me to read anything?” Tilda leans forward like a praying mantis to hold out a few pages off the table that had been in front of her just under her notes and my resume. I get up and reach forward to take it, return to my seat, I look at it. It’s an essay. Margaret wrote it. It’s on Jaruwan Sakulku. I take a quick few seconds to scan the first and last lines, then read it aloud with few intonation or emphatic hesitations. I slow down towards the conclusion. I give Margaret’s emerged thesis weight and sobriety. I read the last line to the four of them, and see that none of them are engaged. They’re leaning back in their seats, eyes drooping a bit and at one point while I had been reading they were passing a menu around. I breathe out all the air I’ve been budgeting.

I breathe.

Mr. Clean says, “Okay, thank you” and the four of them are rising again from their four slouches and they’re waking up from being in a room with me like I have been a blanket or a short night and fresh air has come in and I wonder what they think of the plot and I wonder what they think of me.

I am not my life.

Tilda leans forward and nods at Ponytail and Ponytail gets up to open the door back out to the waiting room and I say “I can do it again -- do you want me to do it again?” but she’s looking at the door and not at me and she says “We’ll be calling people Monday. Thanks for coming in” and I have my bag on my shoulder and I have my skirt smoothed on my thighs and as I pass through the doorway into the waiting room I see a room full of swarthy half-jewish girls who are 5’3” and 250 lbs with ugly hair, ugly hair, and thick, plastic-framed glasses in front of small, deep-set eyes. Ponytail calls out to the room as I head to the hallway, “Chloe? We’re ready for you” and one of these girls with whom I just finished competing stands up and picks up her bag and smooths her skirt over her thighs and she walks towards Ponytail and the door and the spaces I have left for her. She doesn’t notice me as she walks through her own nerves into the audition for the small part in the movie.

The outsides collide with the insides and I am some small thing in the waves.

I am some small thing in the waves.

0 notes

Text

Ambient on Both Ends - Fall 2018

Ambient on Both Ends

With lyrics by The Velvet Underground & Nico, © Verve 1967

I’ll be your mirror, I woke up thinking. Reflect what you are in case you don’t know, it continued, and I rolled myself up, groggily reaching for a glass jug of water at my bedside and gulping it gladly. Joanna hopped down and ushered me into the foyer, where I walked past her clawing at the rug and screaming at me about breakfast. I sat down in the bathroom and put my face in my hands, and the song continued: Let me be your eyes…

More awake now, I stood and meowed back at Joanna, then acquiesced. Once fed, she fell silent and I did, too, but in my head, Nico kept it up: Please put down your hands, cause I see you… Blurry-eyed, I poured coffee from the pot that Matthew made before he left for work, and switched off the coffee maker. My mug said “Hello, gorgeous!” on it but I didn’t feel gorgeous. Standing in pajamas with my hand on my cocked hip and my hair sticking straight up and sideways, I focused instead on the color of the mug: Baby pink with gold trim, and the black coffee that changed to beige with cream, then darkened back a bit with cinnamon. I sat with my coffee and pulled up Spotify, and played the track off the 45th Anniversary album. I released into the real, tangible noise outside my head the prerogative I’d woken up to. It was September in New York, and I was alive.

*

I am dictated daily by two forces: Wind, and eyes. I was walking Pablo in the park adjacent to my building, and I imagined one of my favorite phantoms watching me. He was one of a few men that lived more in my head than in Manhattan, a rotating cast of mirrors. I inhabit them by entering rooms of my mind that offer the shape and texture of real, external people, looking back at myself through their eyes. These representations are meager and limited, but the phantoms provide the feedback that I’m always reaching out for. It’s emotional sustenance and safety in a desperate state, and most precisely it’s a matter of delivery and reception being shoehorned into one moment. On the surface, maybe it looks like performance for vanity’s sake, but my actions are true. I act not for the outward performance but for the infrastructural reinforcement, because what is a moment if it just fades away? External feedback is hard to source, and so in faux observation, I immortalize it, actor and audience, and it lives on not only in unmovable existence but in the combined, fortified memories of my having lived it, and my having watched myself live it; a concert hall hosting hundreds of my iterations, and my phantoms.

The closer I got back to my building, the more the phantom slipped away. We were alone, Pablo and I. He stopped on the corner and his ears perked up, and in the pause I raised my eyes to the grey sky above me. It occurred to me that maybe I was done with my phantom; that he had served his purpose over the last few months, in his vast absence. He was of great use and comfort, but was he just a band-aid on an amputated limb? That I could move forward without phantoms struck me at once as a tragedy, and a lie. The wind washed over me, from my left, and carried me to the right, toward the front door of the building. A world of messages hissed by. A bus sighing on Fort Washington Avenue, a conversation between two passing gentrifiers -- “It’s a crutch.” “Heroin is a crutch. This… this is art.” “But he’d be proud of that?” -- and a film crew: “Rolling, rolling!” The wind is the sympathetic voice of the universe, sad and strong. The wind sighs in busses and edifies through the conduit of passing gentrifiers; talks to me through crashes and whispers and a whistling kettle, through tears and stings and the memories I contain. The wind offers itself to me in gusts. The wind made me, and it forgave me.

*

Juli buzzed my apartment from downstairs, and the sound of Pablo’s nails came clattering across the floor towards the door, where he jumped and stopped short, out of his mind with excitement. “Did Juli come to see you?” I cooed at him. I grabbed our attempt at podcast equipment: An oversized, handmade mug, lumpy in some spots and erratically painted. I pulled up the Voice Memo app on my phone, started the recording, and put it upside down in the mug, which made an acoustic clink that I would hear when I listened to the file the next day. “Is Juli here just to see you, Pablo? Is it Juli?” He jumped half a step backward with each sound of her name, preparing to launch himself over the threshold when his favorite neighbor arrived at his home. Leaving the eleven-pound lunatic in the foyer, I set my phone aside and went back into my room and poured three buck Chuck into a teacup. Then I tidied a pile of mail while I waited, and after a couple minutes had passed, Juli knocked. I looked down at Matthew’s ecstatic dog. “Is Juli here?” He couldn’t contain himself. I opened the door and he threw himself at her ankles, jumping backwards, flinging himself at her again and again.

“Let the record show,” Juli said, stooping to say hello to Pablo with a self-conscious smile, “Emily is an excellent hypewoman.”

“The record does show it, because I’ve been recording for… two minutes.”

“Oh, that’s good, the ambient noise on both ends.” She unloaded her backpack in my room and took off her shoes, pulled my vanity seat towards my bed, and kicked her feet up. “But you’ve got to remember to leave it running longer when I leave.”

“I mean, this is all great for when we have listeners, but you realize it’s just me, obsessively listening to our wit played back, and the ambient noise I include at this stage is only so you don’t yell at me about being off-brand.” I warmed myself with the wine and got my knitting situated on my lap. “I do like it, but it’s gonna take more than that to appeal as idiosyncratic in the long run.”

“What are you talking about?!” Juli shouted with a shock through her outstretched limbs, choosing this battle. “We are the definition of idiosyncratic! People love us!”

“They definitely do, but you know we’re not making any progress on being presentable to the listening public. I mean… we’ve got to get them first, before they fall in love with us enough to look forward to the two minutes of me putzing about before and after the actual episode, because that… that’s real love, Juli. That’s the kind of thing I think we all want, to be included in that intimate way in the lives of our content creators.”

“I hate you,” Juli said, with a smile she pairs with that particular utterance at times when she envies my skills in articulation. “That’s exactly what it is.”

“I will say, though, that what we are doing has been making me think of something a little weird.” I stopped and thought for a moment, unsure how interested she was going to be. If I framed it as self-obsession, she’d shrug it off. But if it was science fiction, she’d insist she’d read it somewhere. “I just can’t remember if I dreamed it, or if it was in some dystopian story.”

I had her attention, and I continued. “In, like, maybe a world where capitalism got really convoluted, like in some exaggerated version of the -- what do you call it, the sharing economy, with Uber and every subway ad being for sheets, which, like, they’re able to do that because people really do give these sheets such good reviews. So it’s like that, with how we all kind of feed off each other’s capital and somehow make a living. And it seemed kind of… dark, but I don’t know what the connotations really are, when someone does this…”

“Does what?”

“People set up cameras, and other, random people send them payments just to watch their life, as entertainment, like, instead of tv.”

“Ummm… ok, wow? That would be a pretty meta thing, in itself? Like, I love it? But I’m pretty sure that’s a real thing.”

“Maybe in some ways this does already exist, with camgirls and stuff, but the reason I brought it up is because it’s occurred to me to set up a camera and just… record myself. Or just audio. Like the two of us do here, but… just me.”

“You’re…” she stopped herself for a moment, then went ahead. “Yeah, you’re insane. But is this, like… is it just for you? Or is it for some guy?” Juli shuddered. She had little tolerance for heterosexual antics.

“Oh, just me… Just like how, at this stage, the pod is.” She relaxed, having gained a sense of what it was I was saying. “And, you know, I asked Blue if I could record our sessions.”

“Marc Maron does that. What did she say? Is she gonna let you?”

“Definitely not. But she gets it… I talk to her about that delivery-and-reception thing. I mean, I know my being crazy is why I’m so drawn to being watched. He was with me all of the time. Now that I don’t hear him in my head anymore, I’m just reaching for anyone that might be out there, to share space and time with… and consciousness. So, audio recordings, video recordings… And how -- you know I do this -- how I always imagine some other person seeing me, following me, when I’m outside. It’s feedback. I know no one would ever want the files--”

“We’re gonna have tons of listeners one day! I’m building a podcast empire!”

“--I know it’s just me, but it really works for me to create a loop, feeding back that I was… That I was here. I really was here. Because just existing isn’t enough.” I thought about adding since he went away, and about how robust the house of my self was, back when I had consistent company in my head. He was overstuffed couches; he was lush carpet. He was walls covered with glittering paintings, and encrypted messages in the wallpaper, keeping me rapt and always curious. He filled the space around me, and I was held. Now, it feels like my thoughts bang off of tin walls and fall flat on a tin floor. Sometimes I get visits, and music pours in my windows, thick and sweet like syrup. We remember, and we hold each other, and we laugh. It’s a laugh that comes straight from the heart and makes no sound; no perceivable impact, just knocks me flat on my ass because it’s borne of the crevices of cranial cortexes and there’s nothing we know better than that territory, nowhere we can see each other more clearly than in those crannies. His puns have eight dimensions. We feed back. And then he goes again, and I have to find some way into a room not made of tin… I thought about telling Juli my skull feels like tin, but I didn’t want to depress her. She’s suffered her own losses.

She shook her head. “Of all the schizophrenics in the world I could be best friends with, I got the one who’s totally fine with -- nay, excited by -- every futurist paranoia there is. You’d never fit in in science fiction. They don’t have Orwellian utopias.”

“It’s not just Orwellian shit, though. I mean -- okay, yeah, there were a couple times I was really scared -- but when you get your Hogwarts letter, it’s pretty hard to pair the magic with self-doubt. And you know what? Go ahead and call it magic. That I never have any fear, now, that I’ve done something wrong, or that anyone has. God… give a girl a voice in her head, hand her a book on radical acceptance, throw her in a hospital for six years, and what you get is this fuckin’ self-assured witch right here.” Juli wheezed her high-pitched laugh at my snowballed delivery, squinting her eyes at me over red, bulging cheeks. We went on like that til one in the morning. A thursday night, delivered and received.

*

Juli mouthed and gestured to me, “keep it rolling” as she walked backwards to the elevator. I shut the door and let the recording pick up the floor creaking and the rustling of plastic as I gave Joanna a few treats, then another clink as it hit the side of the mug when I pulled it out. Then…

Dead air. When I would listen to it on the way home from my session with Blue friday afternoon, I would feel suddenly alone. My head would feel empty; my ears would ache for company. I would rush to put on music, and to the solitary soundtrack of Laura Veirs and John Frusciante, I would choose a phantom to join me on my walk. I would take a few seconds to imagine the person the phantom stood in for, and then I would feel their presence, and I could relax, look forward, move.

But for tonight, I filled a glass jug with water and put it on my bedside table. I turned off the small lamps that lined my room. I put my knitting away, set my alarms for class in the morning. I turned down the covers, slid between the sheets, and felt myself feel myself. I was here.

I was thinking about what novel to write about for a grad school application essay, then I thought about how to start my memoir piece for my prose workshop, and my heart rate increased. I stopped myself, as I do every night. I took a deep breath. I cleared space inside myself. I sank into a flat plane, satisfied, and there was room. I smiled broadly. I felt a presence in the room reflected back at me. To no one, I spoke silently.

“Hey.”

*

0 notes

Text

All Systems Go - Spring 2018

All Systems Go

from prompt: first love

Stop.

I’m in a funeral home on the west side and I’m trying to cement the day in my memory for future use, trying to validate the taste of this sadness in real time and immortalize it. Keep it. Treasure.

Are you being sincere? Stop crying if you don’t mean it.

But my tears are legitimate, I realize, and that’s when it really starts. My eyes won’t stop and I’m not even imagining how I look from the outside. How feminine or thoughtful I might seem to the hundreds of people at this service, spilling out of the room and crammed into the hallway and even standing on the steps leading down to the ground floor. The number of people who show up to bury a kid is overwhelming.

Kevin O’Sullivan is sitting next to me even though he only skated with Lewis a few times but he’s strong and his back is straight; his presence is dense and unmoveable like a support beam and I need it. I say nothing to him as he passes me tissues and otherwise looks straight ahead, stoic, and unfaltering like my grief itself.

The mourners out there can’t hear the eulogy, but it’s that girl a grade above me who tried to cyberbully me one night before Lewis himself stepped in and told her to take a look at herself. He asked her what would compel her to do something so ridiculous and unnecessary. It sounded enough, at the time, like “Emily’s alright, lay off” that I didn’t hear “she’s no threat.”

This girl, whose name is also Emily, was a later adopter of the group obsession with Lewis. I first saw him at the start of sixth grade, in a fifth-floor gym with 300 children, and he had bloodshot eyes. I never did grow out of that taste for sickness. About a dozen more girls at that school deified him in the same way. We wrote his name on our tits and took photos, blew him anywhere and any time he asked for it. Well, but that’s a lie. He never asked me.

This is all there ever will be.

I’m thinking about how we need to earn our emotions but I’m dropping my efforts to achieve as they occur to me. This is unprecedented -- I’m not jumping through hoops to prove my misery, here in this pew. I’m releasing my shoulders and my demands; I drop into my body, weeping and true. I fill the space I’m in.

This is real.

I feel purity first hand, without audience or ego. I fix my wet eyes on a spot on the rich wood of the wall next to me while also-Emily speaks, two feet from the body at the head of the enormous room. The tears come thoughtlessly; my mind is clear but for the sense of gravity in nonnegotiable loss, unattached to objects in the world. My grief doesn’t have a name.

*

Chris Kraus, an artist in the medium of contemporary feminism and author of I Love Dick (Semiotext(e), 1997) wrote about an enigmatic academic, “loving you is like loving a girl. She doesn’t have to do anything. You love her ’cause she’s beautiful.” This distinction between a figure who, in Kraus’ case, was “a portable saint,” whom knowing was “like knowing Jesus” and then, the rest of the world, is an unassumingly convenient polarization. The act of deifying dichotomizes one’s landscape and institutes a loyalty through which to make sense of the rest of it. If I choose to freefall into obsession, generosity, and rabid, blind acceptance, I will always have the answer when I ask myself when to stop. Do the devout question what lengths they are willing to go to for god? I didn’t. It was all-systems-go for Lewis, and having an answer for every situation in my commitment to worship was an unlikely foundation from which I grew, for a few years. He was twigs and strange mucous and I collected my affection for him to build a nest in some bizarre and impossible tree, a vantage point from which to navigate adolescence. Living in love for him was reliable. Then he choked on his own vomit when we were fifteen, and I put it to bed. The alternative has been ambivalence, apparently. Living in greys instead of in love and not looking for black-and-white clarity because it doesn’t need to be that simple if I make up the difference by inventing myself every day, setting expectations and meeting them. Performing.

Do I deserve this?

The only audience I have access to is myself.

Am I earning it?

***

And then, of course, it hit me like a rush hour D train.

Go.

Don’t weep for me. I’m here in my body.

0 notes

Text

Broke Thorough - Spring 2018

Broke Thorough

DAY ONE

Dr. Cousins had been working with patient E for a couple of weeks, and she was next for our team meeting. I was already exhausted after two patients on this, my first day at 11 Greenberg North… but she was the one I’d been looking forward to. I looked around at the other interns to see if they were as eager as I was, but made sure not to show it myself. Along with all the other things this month was, it was also something I needed to be at the head of or else I’d lose my own. I smoothed my pencil skirt over my thighs where I was perched on the radiator and prepared myself for the most psychotic person in the building.

An orderly whose name might have been Angie led E into the conference room by the shoulders, coaxed her softly to sit in a chair opposite Dr. Cousins, and said to him, “I’ll be just outside if you need me.” E was on status, but for an unusual reason: One-to-one care was usually only prescribed when the patient was in pressing danger of hurting him or herself (everyone knew that) but E was on status because she couldn’t move around by herself. There were twenty-two patients on the unit, and all of them could feed and bathe themselves, all of them could get up off the couch and walk to their beds, all of them could helplessly write letters of appeal to a court that wouldn’t read the plea in such earnest and unbureaucratic handwriting… except for E. E would wake up in the morning and be led around all day -- to the dining room, where every day the staff got their hopes up she’d bring food to her lips, and, defeated each time, got a few bites in her through the otherworldly grin she rarely released. They helped her in the shower, getting dressed, sat her down when her parents came to see her. They led her to a couch in front of the TV, where she sat for hours with a gaze fixed on the ceiling, hands resting inside the join of her blue scrub pant legs. It’d been determined she wasn’t self-stimulating, but every time someone managed to get her hands out of her pants, she’d just put them back; it was one of the only things she seemed to be able to do, was put her hands there. With fists together under the fabric and drool oozing down her chin down to her breasts, bare under a matching scrub top, she seemed to demand nothing, while what we demanded of her was impossible.

I learned all of this later, though, along with the fact that there was nothing to be eager about in meeting E, in seeing her see through walls, through eyes, through planes, staring at her friend that never left her, whom we’d never be introduced to outside of his component chemical imbalance, CAT scans, medication trial-and-error. She would be one of thousands of patients I’d have in what became a forty-year career working with the nonlucid, but this was the first day of those forty years, and I’d never yet seen someone in person who’d lifted off.

“Hello. Can you tell me if you know where you are?” She was looking past Dr. Cousins’ right ear as he asked, going through motions he’d had to every monday, for this silent haint. Up at the ceiling she stared, and I swear I saw tears in her eyes at the sight of stale flecks of dust that drifted into the light from the pale of this brutally precise inquisition.

DAY EIGHT

Goddamn it, I swear I’m well-socialized, but patients are terrifying. They reject everything and make me feel like a fucking idiot. What am I supposed to say out loud to someone who can’t hear me because of a problem I’m supposed to fix?

We were in the art studio and I was E’s one-to-one, to get some live facetime into my hours, but I wasn’t strong enough to lift her up when she keeled over forward onto the table, swinging like a hinge from where her legs bent and where she cupped her hands. I wasn’t strong enough to try.

That evening, E’s mother came for visiting hours and saw the purple marks from where E’s forehead had landed on uncapped Crayolas, and she wiped them off of her with spit and thumb.

DAY FIFTEEN

On this particular monday, it was all about an orange sharpie. The nurse’s station was abuzz with apathy.

“I do not get paid enough to wrestle a writing instrument from that girl’s hand.”

“You think she’d fight back?”

“Are you seriously asking me to predict what that child will or will not do?”

“Well, where did she get it?”

“What do you mean, ‘where did she get it’? If we kept track of every little thing on this unit -- you know what? I’m not even gonna say it. You know what would happen.”

“As if we ever do get to go home in the first place now…”

“Mm-hmm.”

Other patients sometimes fought. They sometimes threw things, and kicked, and snuck in life-threatening contraband, and sometimes they fucked each other in between checks, and sometimes they spit. The spit had to be the worst, though. It hadn’t happened to me, but I’d heard Shirley, who wanted to go home and not think about orange sharpies, explain that being spit on by someone who hates you because they’re ill isn’t any less hurtful than being spit on by someone who hates you for some logical reason. Then she said that “more hurtful” doesn’t even begin to cover it, when her Danny is with Mrs. Klee in the apartment down the hall four hours longer than he was supposed to be, so that she can wrestle patient J down with restraints so that he doesn’t strangle patient D, who has a death wish anyway; both of them full-grown boys in their twenties whom patient J considers to be on opposing sides of an imagined war with the illuminati. Shirley said when they spit, it takes a long, hard look in the mirror at home to remember why you come in the next day.

But patient E didn’t pose the same threat as other patients on this unit. There were male patients who had their eye on her, and sometimes she stared back at them, eyes glassy, before erupting in a laughter that was like dreams; a myth; a laugh like nonsense. She was moving on her own now, dancing laps around the nurse’s station, hands out to her sides, but she still hadn’t regained speech. Patient E was a model of hospital behavior: she never caused trouble, because she never caused anything… not change, or impact; she just danced a ballet around the unit like it was a stage, and she didn’t ask anyone to pay attention to the story, or the footwork. She didn’t ask anything, even though we were begging her to want, with everything we had. ‘She’s here,’ I sometimes thought to myself. ‘She really is here.’

There was orange… everywhere.

DAY TWENTY-NINE

It was only I who saw her, in the doorway of her room, pink and naked and trembling with a grin against a backdrop of curved orange lines -- worms and cows and books and mountains -- and she emerged slowly as I came upon the threshold. I took the child by the shoulders, with the few years I had on her and so much gained from what she lacked, and it took but a nudge to ease her back in, away from the world asking of her. She met my eyes.

“Not naked, no,” I said.

“Okay.”

0 notes

Text

I Was Here - Spring 2018

I Was Here

With lyrics copyright Bob Dylan, 1962; Loggins & Messina, 1971; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, 1970

You lost your mind. You lost twenty dollars one time when you needed it most; you lost your favorite dress the next year; you lost your glasses the night you lost your virginity, that winter when the world was gaining on you. You lost the home you lived in. You lost your shit every summer. You lost your first love and you lost, the second time, as well. You lost a Prada bag, and then you found it in the trash. You lost hope; you lost teeth. I saw you lose your teeth. And don’t forget you lost control, track of time, and once or twice you lost sight. You lost your mind; I was there.

You were a genetic victor who lost everything she had the spring the virus spread in North America. Your country was first to fall, and in six days there were no countries left; in seven, no survivors left to tell you. There were busses; there were boats. There were emergency procedures; there were bombs, panic, everyone weak. The illness was in the water but became airborne, at which point the world held its breath, or maybe it was just winded. The walking bodies bled from their pores, dropped limbs from the rot, and when the angry organism of the end times reached the brains of the walking bodies, the howling began. You listened to a wailing world from indoors, and you hugged your knees and wailed yourself. But you, you did not bleed. I was there; you did not bleed.

By the time the TV went silent, the anchors you knew had been replaced, then even newer faces were itemizing what they knew about the Banshee Plague and saying it’d taken half the planet’s people, but never admitting the curtain was falling on the final act of man. You were not told but rather shown, that week, that mortality reached a statistical one hundred percent. You were alone; I was there, but you were alone.

The week the world ended, there were fires and fucking in the streets. The grid went down: no maintenance. You saw a body drop to the ground from a window, cradling two smaller, swaddled bodies. You had seen a fearful vengeance in the eyes of presidents and neighbors; with no hope left, it turned out man never did default to love. You saw disease; you saw hope estranged, you saw power collapse, you saw futures erased. When a species goes extinct on a planet passing through, does it make a sound? It did; you were there. Man wailed through the space of that week when the world of man fell. I was there; I heard you hear it fall.

Your heart beating out of your chest, you checked your mother’s home. She was gone. You stood up from her bedside where her body lay and your muscles did not fail you; strong, you stood up from the chair by her bedside. You walked the Queensboro bridge to check on your girl; your laughing, loyal girl. Along the way you checked faces, but by the time you saw the half of hers that was left, you said ‘no more faces.’ No one was left; you didn’t need to see it. Nothing was coming back. You walked home; through the quiet streets, I walked you home.

It had been torrential fear, but for only a week, and then such a sudden silence that no one could have ever known. Did you hear me in the stillness when you packed pills, bandages, combat boots for your fated trek north in this, the apocalypse of the Anthropocene? Had anyone heard me in the stillness after the Cretaceous? And when Pangea fell, in all that noise, do you think anyone heard me? You hear it now, in your sleep sometimes, noise as dense as wet velvet, meters thick. You hear me now. You hear me, child.

The odor of death was as solid as a wall, on the streets outside after the plague, as you raided pharmacies until you got to the open road. From the bookstore in midtown you added to the pack you carried the Physician’s Desk Reference; the Boy Scout Handbook; Gödel, Escher, Bach; A Brief History of Time. You ate the fruits that Whole Foods left in the extinction; you ate bulk nuts. You packed dark chocolate and vitamins. You gathered hydrogen peroxide, Dr Bronner’s, a water purifier. On the outskirts of the city you collected a can opener and packs of AAs. From the hip of what was once an officer, you took a gun.

When you found a map and readied yourself for the north, you stayed the night in a liquor store where someone, once, had stationed a battery-operated CD player, and you put yourself to sleep with rum and Bob Dylan and the tears he brought, bitter for the world and sweet for the silence that became your company. I lived in that silence, and also in the sounds that pierced it. “Look out your window and I’ll be gone / You’re the reason I’m travelin’ on / Don’t think twice, it’s alright.” It was me; I was there. We lived there together.

With your boots and your bullets and a belly full of pancakes you made on a dead man’s gas range, you were the face of fortitude, and you marched west listing north. Cars lined the roads, surely half-tanked, but they weren’t an A train and you didn’t know how to make them move. And so we walked; I moved my feet in yours. You found your antipsychotics in pharmacy after pharmacy, and you spared some room in your pack for vicodin, xanax, and penicillin. You twisted your ankle going after that pack when it slid down a bramble-covered hill, and when you took the pills that disappeared your father, the ones that killed him in darkness and broke your mother’s heart, you looked up at the sky and willed me to take you. You gorged like nonsense that night on canned peaches roasted in tin foil on a fire ignited with a barbecue tool, dopey from the drugs and eager for the sugar. You were thankful for the excesses of society that were keeping a city girl alive in a dead, still world. Then you walked on, willing that ankle to stop you, to keep your body in the south, the stinkingest land in a hot country on an empty continent in a festering world. You willed it all and me to take your body, to keep it, to leave you unencumbered by it. I was there when you cried all night, shouting at stars, and I was there when you woke up in the morning, unburdened by the volume of the tears.

I was there when the first puppy ran up. A well-fed shepherd mix, she’d been bred to trust what was now the waste of this land, but you were all that was left, walking north. She looked to you for the Alpo and the warmth that you gave her each night, in beds you passed through off the highway. You didn’t give her a name, because you didn’t know any that weren’t in memoriam, but when the second dog ran up, you began numbering them. “One!” you called, and she came. “Two” got his attention when he got too close to infected meat. Then Three, a husky like Two, and Four, a pit. Five was a retriever, and he liked to bring you ducks, greasy and satisfying over flames by the rivers you kept along. Six was the smartest of the pack, another shepherd, and when you started filling notebooks in hours of rest, you drew him, and what looked like sorrow in his eyes. You left the notebooks on tables and in microwaves; in nightstands; under pillows; one ziplocked under a rock in Appalachia. “I was here,” you wrote on the last page of each. I saw you sign each one but you weren’t leaving them for me; they weren’t for me, because I was already there.

You had gotten all the way to Minnesota by January and you’d by then lost fifty pounds and you were starting to remember me and you knew how to stay warm and you knew how to live and you knew not to die when you heard a man.

“Unnhhh… Yeah… there it is. Unh. Yeah. Okay.”

He was strangling a chicken in the backyard behind a farmhouse painted white and blue. You had approached the house for its protein offerings and bedding and maybe some fermented goods; an early evening’s ease for the body and mind. From behind a bush bordering the coop, you watched this six-foot creature toss the dead bird with a thump onto a stump with weathered axe welts in its surface. He was brolic, in a luxury flannel unknown in Brooklyn but revered on campsites, and his dark beard and curly hair showed signs of good health. And he was alive.

Silent behind the bush, you watched him lean into a low-seated wooden lawn chair with his back to you and the moist musk of indica started twisting from his face. A rifle was propped against the chair. One through Seven had been hunting by a lake a quarter mile from the house, and you could expect one or more dogs to follow your scent, and rush towards his, any minute. You were paralyzed by the potential of a living man; you were living in indecision, without a clear motive to avoid his discovery, living ability to use a firearm, or, you began realizing as his broad shoulders and what was sure to be the scent of human testosterone testified against your fear, his desire. The sun was setting. He got up and went inside the house. You stayed put, the zipper of your parka pulled back behind your pistol, its metal warm from your hand on it as you watched the candlelit house and heard him, pans, consternated shouts and a bit of unhinged laughter from the kitchen inside, and you did not hear me. I was there, but in these sounds, you did not hear me.

You stayed crouching there for another half hour, and Four found you. The noise was unignorable; the man emerged. He walked towards the cautious dog with outstretched hand and tonal promises of safety. “Hey, girl, you wanna come sleep inside tonight?” Her guttural whimpering let loose a bark, and you stood.

Your now-long hair blew in sunset wind and you regarded the man, your back so straight it spoke for you; a firm and stoic spine, clear resolve against his charms, his living human charms. He stood, still, too, and the red and purple sky watched you there for six full minutes. I watched you watch each other there for six full minutes.

He spoke first, angling himself towards you, disbelieving. “You… you seen anybody else?” Your hand on your hip did not betray your weapon beneath it, but still, you were undecided. Another minute. “Please, tell me you…” He looked at his feet, gathered himself with a quick deep breath, and raised his gaze to you again. “Please, speak English,” his face crinkling to beg.

Your hand fell to your side and he saw what it had been gripping. “Just you,” you finally gave him. You both stayed standing still as the chickens made ambient feathery sounds beside you, and Four sat panting at your heel.

He began to walk towards you, but two steps in, the sweet pit raised her hips to stand and settled her voice into a low, steady note. “Shh,” you whispered, lowering yourself to put your hand to her head, your eyes fixed on him from three feet down. Again, she sat. Again, you stood, and from behind your glasses, your eyes worked in reverse to the rest of you, to stay right on him.

“That -- that’s a good dog you got there. I got a few myself, but… they come and go. She your only one?”

“Six more coming.”

“From where?”

“Nearby. Last saw ’em by the lake down there past town.”

“And… and you? Where you comin’ from?”

“Far.”

Another silence settled. The house behind him, so big and he, too, so big, so well-rested. No bruises showing, no limp. No scratches on his face like the ones on yours that tended to leave and come back only angrier, and the worse ones on your back. That one deep gash on your ass, on the left, that took three weeks to scab. The sky was turning navy, and the white house began to look grey, the blue shutters black. Small yellow flames inside lit up the walls, with framed pictures, a mirror. He watched you watch the home, the life inside it. “Why don’t you come on in? I… I got tea in there, I do it over the fireplace. There -- uh, there’s breads. I made ’em this week. Looks like you maybe haven’t had bread in a while. And I -- I got whiskey. Some… uh, some water I can heat up, for the bath, too.”

You looked down at the ground for a few moments, felt yourself almost lose your balance at the thought of the inside of that house and at the thought of the man who lived there. You glanced at Four, then you leaned back into the night, pitched your your call to the dogs, and aimed yourself at the house. Walking past him, you said, “I’ll take some whiskey in the tea.” Then, barely beckoning back to him where he stood watching you glide over the lawn, you confirmed his suspicion. “I don’t even remember what bread tastes like.”

*

He was domestic, donning an apron to feed you when you’d finished your soak, and he prayed. Seemed more for show or maybe courtesy, but as he thanked me, you were already halfway through that first lump of baked flour, egg, and yeast that he’d plated for you. With it he’d served pickle chips, a scoop of strawberry preserves that took up half the plate, a bowl of greens you were wary of, a single Saltine, and chicken thigh and leg. The pickles you planned to leave ignored but the cracker, you knew, was a treasure, so you saved it for last. While you ate he told you how far the river was, how often he went for water, what supplies were closest, and the livestock on the surrounding farms he kept on top of. Some of the animals, he said, he’d just opened the gates -- too big to get through after slaughtering -- but the smaller ones he managed to make the most of. Sheep, goats, the chickens here and down the road, breeding, and plenty of eggs. One horse that’d died on her own lasted a while and didn’t make him sick, and he checked in once a week on the five others fenced in on that ranch. The stores, he said, were plenty good on canned stuff and he’d done what he could with the produce before taking what had rotted and burning it in the parking lots so the pests wouldn’t come, or some absurd bacteria from the old world. He’d salvaged seeds from the nursery and some dead friend had had some danker ones. When he went into town for anything, he switched out cars, checking around about which ones had the most gas in them, and keeping a list of where he left the best-running ones. Surprised you weren’t driving at all, he asked what you’d seen as you crossed the country so slowly.

The dogs had all come and were sniffing around his -- a spaniel and a lab in the house, Roxy and Al, and one beagle, Frank, was running around outside with Seven, your boxer -- as you sat with him on the couch with a tealess mug of the amber stuff, legs tucked under you with your tent-like flannel to your knees. You told him about how hard it’d been to learn as you went, no survivalist: How to start a fire without a lighter, how to keep a moving foot bandaged. The months it’d been since you saw a human face -- since either of you had seen a human face -- you’d found laughter when the dogs had, and you’d entertained yourself with stories from the old world, in libraries and bookstores. There were things you kept your eye out for -- pills, glasses close to your prescription, animals that needed help. You spent whole days in lakes, over the summer, and all day long you’d smelled the life that remained around you.

“Well, you’re here now. I’ll teach you how to drive… Maybe we could find more…” he choked. He teared up. He grasped his palms to his knees in suppressive weepy desperation, as men once did, then he looked to you. “Maybe we’re not the only ones.”

But you were never going to stay. That night, you did not let the dogs take him when he fucked you as if it were the first time of the rest of your life. He would be the last to touch you, and so for the first time since you started your way north, you shut the dogs outside the bedroom door. Inside you, he let out a song that rang through the night. He collapsed to your side, holding you, while you looked out the window at the stars and asked them how you were going to get away.

*

“There’s nothing to be afraid of,” he said as he gave you a push up into the cab of a red pickup truck. “It’s as easy as riding a bike, I promise.” You felt the hugeness of the machine all around you, dwarfing you in size and in threat. “There’s nothing safer than an empty road. There’s no way to crash. And look -- the CD players in ’em still work.” He opened the glove box. “Looks like we got… John Denver, Decembrists, the Dead, Faces, uh… Chris Isaak, and… Fleetwood Mac.”

“Stevie, definitely.”

“Huh?”

“Rumors,” you said, pointing to it, and he loaded the disc. “I’m not afraid of crashing.” You gripped the wheel and stared it down, the first enemy to defeat here. “I’m afraid of being in control. This thing is huge -- I don’t even like making decisions for myself. I’ve never wanted to make decisions for this… giant robot creature.”

“Ha! ‘Robot creature.’ I like that. Did you ever watch Transformers?” You shook your head. “Man, I loved Transformers when I was a kid. I remember my… my mom got me a lunchbox with them on it and it was my favorite thing for like two years.”

“I never watched it, but one time this guy I dated for a little while was telling me the arc about the one -- Optimus Prime -- because when he put the soundtrack on I didn’t know what it was. He really got me invested in why this guy was so important, and then he’s telling me the story of that one big fight, with the big bad --”

“Megatron.”

“Right. Megatron. And this guy’s got me near tears with how much I care about Optimus Prime, and that’s when the music comes on, the track from the movie --”

“‘The Death of Optimus Prime.’ Man. I’da cried, too. That guy had moves.” He laughed, then the two of you sat silent for a minute while Second Hand News played maniacally from the car’s speakers, the key resting in the ignition, and he fiddled with a pocketknife in his dirty, calloused hands. “Do you ever feel guilty?” he asked, without looking up.

“About surviving?”

“Yeah.”

“I don’t think about it. It just is. I… I don’t negotiate with reality.”

“I… I wish I could have saved my mom. I don’t know how I would have done it, but I just wish I could have taken her place. But then I think… what if there’s a reason I’m here, and she’s not? It’s felt this whole time like it was the rapture, and all I know is that I’m still here. Everyone’s in god’s kingdom but me. Then… then you come, and you’re perfect. But if we haven’t done anything wrong, why couldn’t we have gone, too?”

“But we… we are there. I don’t think your mom is in heaven. I think she’s in the ground where you buried her.” He looked to you with a confused ‘fuck you’ in his eyes. “Just... look at this,” you gestured to the trees through the windshield, bare and grey and resilient and actual against the modest, generous grey sky. “It all is. It all really is.”

You sang along with me. “Thunder only happens when it’s raining…” You felt me in the wind, tickling your arm through the open window, saying ‘I am here.’

*

On the third day of baked goods and kissing in a cornfield, he spoke to your womb, and the future. You’d been washing the tableware of his old world in two metal buckets of river water with a small flame under one, and he leaned over the railing of the porch towards where you knelt below. “What are those pills you take, anyway? The blue ones you got so many bottles of?”

Underwater, your hands shook. You scrubbed a moment longer, then leaned back on your ankles to face him. Speaking in your vaguenesses, you said, “They keep me here.”

“Do you have, like, a disease? Oh god, I’m not gonna lose you to some bullshit like cancer, am I? Please tell me you’re not sick, baby girl.”