Text

“From mid-1525, government documents do refer to her as Princess of Wales. For example, the grant of the office of Chamberlain of South Wales and the Counties of Carmarthen and Cardigan to Sir Giles Grevile, dated 14 August 1525, refers to him as having been ‘in the service of Mary, Princess of Wales’. Similarly, the grant of office to Walter Devereux, Lord Ferrers of Chartley, in 25 May 1526, appointed him to be ‘steward in the household of Mary, Princess of Wales and Chamberlain of South Wales, Carmarthen and Cardigan’. There is also a patent of March 1529, granting £10 per annum to Margery Parker, ‘servant to the Princess of Wales’. So, while Henry did not issue formal Letters Patent, the title was used in documents and grants, Mary was referred to as Princess of Wales and, by inference, was his heir. Similarly, a despatch from the Imperial ambassador in Rome, the Duke of Sessa, dated 25 August 1525, called her Princess of Wales. Charles, too, used the term in his letters. ”

- The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary, Melita Thomas, 2017.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary was not in London to offer comfort to her brother while his uncle’s regime collapsed, but she knew more than most people about what was happening and the manoeuvrings behind it. She told Van der Delft that she had been approached to give her support to Somerset’s overthrow, but had declined to get involved. While things remained uncertain, this was wise, and it may also have increased her stock with the council, who continued to view her as someone who must not be ignored. They wrote to Mary and Elizabeth on 9 October (though the letter was primarily intended for Mary, as the heiress to the throne): ‘Because the trouble between us and the Duke of Somerset may have been diversely reported to you, we should explain how the matter is now come to some extremity. We have long perceived his pride and ambition and have failed to stay him within reasonable limits.’ They had been alarmed by the duke’s accusation that they wished to destroy the king and his behaviour at Hampton Court, where he had ‘said many untruths, especially that we should have him removed from office and your Grace made regent, with rule of the king’s person, adding that it would be dangerous to have you, the next in succession, in that place. This was a great treason and none of us has by word or writing opened such matter. He concluded most irreverently and abominably, by pointing to the king and saying that if we attempted anything against him, he [the king] should die before him.’ No wonder Edward had been petrified. The council went on to explain that they had ‘quietly taken the Tower for the king and furnished ourselves with the help of the City of London, which was loyal to the king before the Tower was ours’. They reported that the duke had removed Edward to Windsor and hoped that God would help them ‘deliver [the king] from his cruel and greedy hands. If it should come to extremity’, they added,‘which we will work to avoid - we trust you will stand by us.’

The council’s communication to Mary referred directly to a question about the coup, and the confused months of wrangling that followed it, that has never been fully resolved. Was Mary, at any point, offered the regency? Nowadays, such a robust denial would be taken by a cynical media as proof positive that an approach had been made. Merely by acknowledging the possibility that she could undertake such a role, the council were giving it credence. It seems likely, then, that feelers were put out and that some, at least, of the new privy council considered her a viable candidate. The imperialists would certainly have backed her and, for a time, Van der Delft and others believed that the removal of Somerset was a victory for conservative forces and presaged a return to the old faith. The princess could come out of her semi-exile and use her influence to reimpose the religious settlement of Henry VIII. They were, however, deceived. For two months, the direction that the new government would take hung in the air, as a struggle for power on the council ensued. When it was over, Warwick emerged as the leader of England’s government. He soon made it plain that he had no intention of abandoning religious change; in fact, he would press forward, with Cranmer’s support. All mention of Mary as a regent disappeared.

In truth, she had missed her opportunity. Yet it was a decision taken deliberately. The assertion that Mary would have been an ideal choice because she would not have interfered with the normal process of government is hard to justify. She was known for being a hard-headed woman of strong views, and it seems inconceivable that she would have been content to act as a royal figurehead. Arundel was still in touch with her at the beginning of November, but she could not be persuaded. Though she had been a political outcast for most of her adult life, Mary was no shrinking violet. She would have done much to return her brother to the religion in which she herself had been raised.The reason she failed to grasp the nettle was dislike and distrust of one man above all: John Dudley. ‘The earl of Warwick’, she told Van der Delft in January 1550, ‘is the most unstable man in England. The conspiracy against the Protector has envy and ambition as its only motives.’ — Linda Porter, Mary Tudor: The First Queen

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Paradoxically, however, although Mary’s pregnancy appeared to strengthen Philip’s position and power, linking discussions of his coronation with the imminent birth of an heir placed him in a position not unlike that of former queen consorts: except for Catherine of Aragon, whose coronation took place at the same time as that of Henry VIII, plans to crown Tudor consorts were usually connected with the proof of their fecundity. For example, King Henry VII’s wife Elizabeth was crowned only after she had borne a son. According to Charles T. Wood, the fact that Elizabeth had a better claim to the throne than Henry VII meant that ‘before a non-threatening coronation could take place, Elizabeth had first to produce a son, a male whose rights would supersede her own’. Of Henry VIII’s wives, Anne Boleyn’s coronation took place during her pregnancy, plans to crown Jane Seymour after the birth of Edward were thwarted only by her untimely death, and rumours of Katherine Howard’s imminent coronation circulated during a progress to York when it was believed she was with child. Although Renard believed that ‘in England the coronation stands for a true and lawful confirmation of title, and means much more here than in other realms,’ he presented the case for Philip’s coronation to Mary by citing ‘the precedent of Queen Catherine, her lady mother, who was crowned,’ implying that it would give Philip no more power than that enjoyed by a queen consort.”

Sarah Duncan, Mary I

25 notes

·

View notes

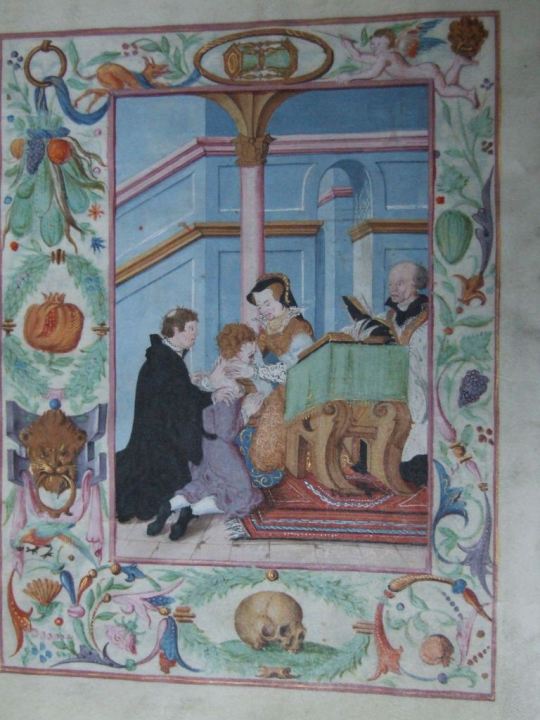

Photo

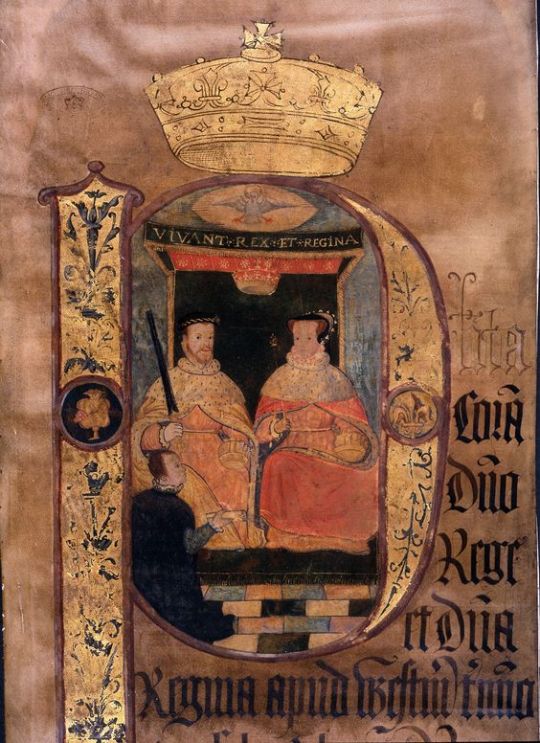

Some historical depictions of Queen Mary of England, depicted in manuscripts. It also contains “the statutes of the Order of the Garter that was presented to François can be seen to the left. At the bottom there is a woman holding together the Tudor rose and the French fleurs-de-lis, indicating the unity between the two kings. She is Concord and it has been suggested that she is representing Princess Mary, whose marriage to the French prince would cement the treaty.”*

Links: https://melanievtaylor.co.uk/2020/04/09/the-good-friday-ceremony-of-the-blessing-of-cramp-rings-and-the-curing-of-the-kings-evil/; National Archives UK’s page on Pinterest website; https://museumstjohn.org.uk/order-briefly-restored/; http://mary-tudor.blogspot.com/2009/05/marys-betrothal-to-henri-duc-dorleans.html [*]; https://www.ucl.ac.uk/early-modern/events/2016/sep/mary-i-1516-1558-conference-her-500th-anniversary-year

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Stanhope and Mary Tudor

as promised for blackwidowsredledger. A look at the relationship between Mary and Anne Stanhope.

To begin with, we have to clear away any preconceived ideas about Anne Stanhope- put into our heads by the Tudors and historians such as Alison Weir who tend to over play drama for audiences.

Far from a manipulative nymphomaniac-as she is presented to us in the Tudors, or an overambitious arrogant bitch who had her husband under her thumb, Anne Stanhope was actually a deeply religious, moral woman, who patronized many evangelical works. She was an active player in the politics of her day, often assisting her husband Edward to maintain the Seymours position, and later when Edward began to be criticized, one of his contemporaries main complaints was that he was dependent on her, and that she dominated him. How much of that was true and how much was made up to make Edward seem “un-manly” is up for debate, but its doubtful Anne was any worse than any of her other powerful lady contemporaries, and probably a good deal better than her male.

Edward and Anne did have a seemingly happy marriage, it’s believed that Edward fell in love with her when she was a lady-in-waiting to Katherine. And she gave him a good deal of children (all of whom were actually his, not other men. For all her “faults”, it doesn’t seem her fidelity to her husband was ever called into question)

Anne was Evangelical, and there isn’t anything to suggest her belief wasn’t genuine. She ordered her servants give Anne Askew and Thomas Bacon said Anne Stanhope was charitable to the poor and a good and pious woman.

However, as with a surprising amount of women, Anne Stanhope didn’t seem to let her religious affiliation tangle to deeply in her female friendships, as well as who she felt loyalty to. Anne Stanhope first entered the court as a Maid of Honor to Katherine of Aragon (meaning Anne was probably serving the same time as Jane Parker), tradition holds that was when she caught Edward Seymour’s eye. Many Evangelical women actually sided with Katherine of Aragon, and viewed Anne Boleyn-even with her own genuine belief in Evangelicalism, or Church Reform-as a whore and a homewrecker. Anne Stanhope seems to have been one of them.

And it seems that while serving Katherine-Anne made the acquaintance of the Princess Mary. We don’t know when the two met or how they became friends, but know a very warm relationship existed between them. Mary was naturally a very giving woman, her purse records are full of examples of her giving ladies and their servants money-she paid a few times for some minor repairs for Jane Parker after the woman was widowed-and gave her ladies money on occasion. Anne’s name shows up several times in these records, usually under the pet name “Nan”. “Nan” is also the name that pops up for Anne Stanhope in records of New Years gifts that Mary gave and received.

But gift giving isn’t the only evidence we have. Mary also wrote to Anne and would refer to her as both a “My Good Gossip” and “My Good Nan”, and always signed herself in these letters as being a good, affectionate and steadfast friend. The two also paid each other visits and enjoyed playing cards with each other throughout the 30s and 40s.

When Anne had children Mary visited, and often paid money to the midwife and the nurse. She also gave money for the child’s christening.

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

In certain things she is singular and without an equal; for not only is she brave and valiant, unlike other timid and spiritless women, but so courageous and resolute, that neither in adversity nor peril did she ever display or commit any act of cowardice or pusillanimity, maintaining always, on the contrary, a wonderful grandeur and dignity … it cannot be denied that she shows herself to have been born of a truly royal lineage.

-THE VENETIAN AMBASSADOR GIOVANNI MICHIELI

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 18 1553, Mary wrote her first written declaration, issuing a proclamation where she declared herself Queen, in a way that mirrored her grandfather's actions the century before when he defied the government of Richard III and with the help of another earl of Oxford.

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary was not in London to offer comfort to her brother while his uncle’s regime collapsed, but she knew more than most people about what was happening and the manoeuvrings behind it. She told Van der Delft that she had been approached to give her support to Somerset’s overthrow, but had declined to get involved. While things remained uncertain, this was wise, and it may also have increased her stock with the council, who continued to view her as someone who must not be ignored. They wrote to Mary and Elizabeth on 9 October (though the letter was primarily intended for Mary, as the heiress to the throne): ‘Because the trouble between us and the Duke of Somerset may have been diversely reported to you, we should explain how the matter is now come to some extremity. We have long perceived his pride and ambition and have failed to stay him within reasonable limits.’ They had been alarmed by the duke’s accusation that they wished to destroy the king and his behaviour at Hampton Court, where he had ‘said many untruths, especially that we should have him removed from office and your Grace made regent, with rule of the king’s person, adding that it would be dangerous to have you, the next in succession, in that place. This was a great treason and none of us has by word or writing opened such matter. He concluded most irreverently and abominably, by pointing to the king and saying that if we attempted anything against him, he [the king] should die before him.’ No wonder Edward had been petrified. The council went on to explain that they had ‘quietly taken the Tower for the king and furnished ourselves with the help of the City of London, which was loyal to the king before the Tower was ours’. They reported that the duke had removed Edward to Windsor and hoped that God would help them ‘deliver [the king] from his cruel and greedy hands. If it should come to extremity’, they added,‘which we will work to avoid - we trust you will stand by us.’

The council’s communication to Mary referred directly to a question about the coup, and the confused months of wrangling that followed it, that has never been fully resolved. Was Mary, at any point, offered the regency? Nowadays, such a robust denial would be taken by a cynical media as proof positive that an approach had been made. Merely by acknowledging the possibility that she could undertake such a role, the council were giving it credence. It seems likely, then, that feelers were put out and that some, at least, of the new privy council considered her a viable candidate. The imperialists would certainly have backed her and, for a time, Van der Delft and others believed that the removal of Somerset was a victory for conservative forces and presaged a return to the old faith. The princess could come out of her semi-exile and use her influence to reimpose the religious settlement of Henry VIII. They were, however, deceived. For two months, the direction that the new government would take hung in the air, as a struggle for power on the council ensued. When it was over, Warwick emerged as the leader of England’s government. He soon made it plain that he had no intention of abandoning religious change; in fact, he would press forward, with Cranmer’s support. All mention of Mary as a regent disappeared.

In truth, she had missed her opportunity. Yet it was a decision taken deliberately. The assertion that Mary would have been an ideal choice because she would not have interfered with the normal process of government is hard to justify. She was known for being a hard-headed woman of strong views, and it seems inconceivable that she would have been content to act as a royal figurehead. Arundel was still in touch with her at the beginning of November, but she could not be persuaded. Though she had been a political outcast for most of her adult life, Mary was no shrinking violet. She would have done much to return her brother to the religion in which she herself had been raised.The reason she failed to grasp the nettle was dislike and distrust of one man above all: John Dudley. ‘The earl of Warwick’, she told Van der Delft in January 1550, ‘is the most unstable man in England. The conspiracy against the Protector has envy and ambition as its only motives.’ — Linda Porter, Mary Tudor: The First Queen

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Mary had also decided on a grand public display rather than a private wedding, according to her prerogative, just as in times past a king could be married ‘prively or openly’. Although Judith M. Richards has argued that royal weddings in England tended to be private occasions and that, in contrast, ‘the procedures were very different’ for the unusual event of a regnant queen’s marriage, the choice of public or private ceremonies in fact depended on circumstances specific to each Tudor marriage. Henry VIII’s wedding to Catherine of Aragon in 1509 at Greenwich had been a quiet, speedy affair so that she could share his coronation; his marriage to Anne Boleyn had to be conducted secretly in 1533 because she was pregnant and the annulment of his previous marriage had not yet taken place. Henry’s nuptials with Jane Seymour had occurred shortly after Anne Boleyn was beheaded by the king’s order, and the obscene haste of the match likely called for some discretion at the wedding. Henry VIII’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, arrived on January 3, 1540, and was married three days later in a season of the year when the church forbade marriages, a fact that may have limited the festivities. The circumstances of his nuptials with Catherine Howard on July 28, 1540, echoed the unseemly haste of the Seymour wedding: Henry and Catherine were married only 18 days after his previous alliance was annulled and on the same day that Thomas Cromwell was beheaded. Mary would hardly have wanted to study these marriage ceremonies as exemplars.

The Tudors, however, were also capable of grand, extravagant weddings. Catherine of Aragon’s first marriage to Prince Arthur in 1501 had been a lavishly opulent, grandiose public affair within St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, with King Henry VII, his queen, Elizabeth, members of the royal court, and city dignitaries all in attendance. There had been a procession through the streets of London before the wedding and banqueting and a tournament after it; and the festivities, including dances, masques, and jousting, went on for a week. It is more likely that Mary I took her mother’s first wedding to Prince Arthur rather than her father’s marriages for her model. Whatever the inspiration, Mary I the city of Winchester provided a convenient meeting point and marriage site for Mary, journeying from London, and Philip, arriving from Southampton. The queen issued a proclamation on July 21 ordering that ‘all noble men and gentlemen, ladies and other apointed by her maiestie to attende upon her grace’ at the wedding ‘doo with all convenyent spede make their repaire to her grace cytie of Wynchester, there to give their attendance upon her’. Summoning the peers of the realm to witness this important ceremony turned it into the kind of magnificent public occasion that England had not witnessed for some years. In addition, the participation of England’s nobility, the country’s leaders, validated Mary’s choice of spouse and potentially created an aura of widespread support for the queen and her husband while overcoming the spectre of resistance to the Anglo-Spanish alliance.”

Sarah Duncan, Mary I

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“There’s no denying [Mary] did some terrible things in her life. But also, not many people get out of British history without doing some terrible things. I find it very interesting that our first female monarch, we managed to go, ‘Oh, she was Bloody Mary. She was terrible compared to the really good one that came next. ‘Cause that was the good woman.‘” Reiss said, “And I’m like, ‘Of course we did that.’ […] I think there’s pleasure in trying to excavate a real person from the maligned horribleness that people say about her. She’s not a great person, that’s for sure. But I don’t think Elizabeth is, either.”

— Anya Reiss on Mary I

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝐑𝐎𝐌𝐎𝐋𝐀 𝐆𝐀𝐑𝐀𝐈 as 𝐌𝐀𝐑𝐘 𝐈 𝐎𝐅 𝐄𝐍𝐆𝐋𝐀𝐍𝐃

BECOMING ELIZABETH (2022)

244 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A study of Mary I’s coronation:

“Renard had to request that the bishop of Arras send holy oil for the ceremony, because since the country was under papal censure its oil was unhallowed. The bishop had sent three phials from Brussels, with a wild boar from the queen dowager for the celebrations after her coronation.

As was customary on the eve of a coronation, she created fifteen knights of the Bath, who “according to thorder every man to bere unto the quenes Ma.tie. at her fyrst course a dyshe of mete”.“ At one in the afternoon on the 30th September, Mary Tudor left the Tower and proceeded to Whitehall along the traditional route with ”many pagenttes in dyvers places as she came by the wey in London, with alle the craftes and aldermen“.‘

Preceded by knights, bishops and judges, her council, the knights of the Bath, the marquis of Winchester bearing the mace, and earl of Oxford the sword, she proceeded, according to the Tower chronicler,

sytting in a charret of tyssue, drawne with vj. horses, all betrapped with redd velvett. She sat in a gown of blew velvet, furred with powdered armyen, hangyng on hir head a call of clothe of tynsell besett with perle and ston, and about the same apon her hed a rond circlet of gold, moche like a hooped garlande, besett so richely with many precyouse stones that the value therof was inestymable; the said call and circle being so massy and ponderous that she was fayn to beare uppe hir hedd with hir handes; and a canopy was borne over the char.

The coronation device of Henry VII preserved in the Rutland Papers specified that a king should wear ”a long goune of purpur veiwet, furred with ermyns poudred“ and travel beneath a canopy of bawdkyn cloth of gold; identical to the description in the herald’s account. The queen consort (in Henry’s case) was to wear ”a round cercle of gold" and travel in a litter.’ Mary was a hybrid mixture of elements appertaining to a king and a consort. In contrast to the Tower Chronicle, the official records describe her wearing white cloth of gold, the prescribed dress of a queen consort. Judith Richards has argued that the contradictions in the accounts of her appearance on the 30th, whether as “a queen qua royal wife dressed in white cloth of gold or a monarch dressed in blue or purple velvet” reflected uncertainty about Mary’s position and authority. An uncertainty produced by her gender, over the meaning and significance of a coronation of a queen regnant.

She was followed by Elizabeth and Anne of Cleves in a second chariot and then by forty-six gentlewomen. The streets were gravelled and railed on one side “to the intent that the horsys sholde not slyde on the payene mente nor the people shold not be hurte by the said horsys”. The crafts and aldermen stood within the rails and on every side the windows and walls of the streets through which the procession passed were “garnisshed with cloth Tapistry Arras cloth of gold and cloth of Tesshew with quishiones of the same garnished with stremers and baners as Richely as myght be devysed”.'

There were “in many placis ordained goodly pagents and devissys and therm goodly great melydy and eloquent speeches of nobyll historis treatinge the joyfull coniminge and recepte of so noble a quene”.’ There is little extant material on the pageants and what there is, is mostly found in accounts published abroad. The coronation was an event celebrated predominantly on a European stage. It was a significant political event.

The Genoese triumphal arch at Fenchurch Street bore two inscriptions: “Mariae Reginae inclytae constanter piae coronam britanici Imperii et palmam uirtutis accipienti Genuenses publica salute laetantes cultum optatum tribuunt” and “Virtus superauit, Justitia dominatur, veritas triumphat pietas coronat salus Reipublicae restituitur”.'

The Florentine triumphal arch at Gracechurch, was graced by three female icons: Pallas Athena above the inscription Invicta virtus, Judith Patriae liberatrici, and Tomyris liberatis ultrici.'Allusions to Judith’s triumph over Holofemes (who the “Almighty Lord brought… to nought by the hand of a woman”) and the victory of Tomyris over all-conquering Cyrus, were topical, a month after the execution of Northumberland. Both women had decapitated the defeated.’ The analogy between Mary’s victory over Northumberland and Judith’s salvation of the Hebrews from bondage to Nebuchadnezzar, figured the Marian rise to power as a providential religious victory over the Protestant anti-Christ. Holofernes asserts in the apocryphal story, “who is God but Nebuchadnezzar”.’

[…] The figure of the warrior queen was one solution to the problem of how to represent Mary. However the virago was an equivocal figure. The praiseworthy assumption of masculine charactenstics contradicted de facto gender. The insciption underneath the icon of Pallas Athena on the Florentine arch, translatiable 'invincible manly excellence’, embodies the problem created by praise of women.

It inevitably drew on terms belonging properly to the celebration of masculine virtules. The problem of finding representations suitable to queenship in Tudor England was apparent in Robert Wingfield’s description of Mary’s decision to claim the throne, as 'of Herculean rather than of womanly daring’. The ambiguity towards queenship in the pageants was also apparent in the coronation itself.

On the 1st October, Mary travelled by barge to Westminster and the Parliament building. There she apparelled herself in “her parlement robes of crymsyn veluit under a rich canapye of Bawdkyn… with iiii stauis and iiii belles of syluer accordinge to theold precydoure borne by the barouns of the v ports”.

She then proceeded to the church for the coronation. She 'lay prostrat’ on a velvet cushion before the altar, while the oration Deus humilium was said over her, a formula identical to that of Edward Vi’s coronation: then “shall the King falle groveling before the Awltare, and over him tharchebushope shall saye Collet Deus humilium”.'

The ceremonies reproduced almost exactly those of her predecessor Edward’s; retaining changes which had been made to the forms employed by Henry VII and VIII. However there were two significant changes to the Edwardian ritual. At the suggestion of Stephen Gardiner, Mary had studied the wording of the coronation oath. A minor emendation was made to the first section, “Will ye grawnte to kepe to the people of Englande and others your realms and dominions the lawes and liberties of this realme and other your realmes and domynions?”, with the insertion of the words 'the just and licit laws of England’. Gardiner’s legal challenge to the publication of the First Book of Homilies on the basis of subsequently repealed legislation, suggests one interpretation of the change might be that it protected Mary from the accusation of violating her oath, in not upholding Edwardian statutes underpinning a religious settlement inimical to her conscience.

Such an argument, however, threatens an infinite regress. Since Gardiner’s case for the unjust and illicit nature of the homilies rested on an existing statute which was quickly repealed. Whereas Mary could have cited pre-Reformation legislation to support a case against Edwardian innovations. But how did an appeal to unrepealed statutes which could easily by implication be rescinded affect the status of any particular existing law? This was a paradox of the Tudor constitution. The contrast between Henry Vifi’s Third Succession Act (1544) which made its own “interruption, repeal, or annulment” high treason and his Bill for Wales (1543) which provided for its own modification by letters patent exemplifies this problem about the status of constitutional law.'

The second change was that while Mary “promissed and sware upon the sacrament lyinge upon the aulter in the presences of all the people to obsarve and kepe” her oath, Edward had predictably sworn on the bible by the “Holy Evangelistes by me bodily towched apon this Holy Awltare”.’ The development of the coronation oath from the late fifteenth to the mid-sixteenth century is a fascinating gauge of political and religious changes. […]

“Wole ye graunte, and kepe, to the peple of England, the lawes and customes to them as of old rightful! and devoute Kinges graunted, and the same ratefie, and confirme by your oth, and specially the lawes, customes, and liberties, graunted to the clergie and peple by your noble predecessor and glorious King Saynt Edward?"

"Will ye grawnte to kepe to the people of England and others your realmes and dominions the lawes and liberties of this realme and others your realmes and dominions?”]

"I graunte, and promitte.“

"Doe ye graunte the rightfull lawes and customes to be holden, and promitte ye, after your strenght and power, such lawes as to the worshippe of God shalbe chosen by your peple by youe to be strenghted and defended?"

["Do ye grawnte to make no newe lawes but such as shalbe to thonour and glory of God, and to the good of the Commen Wealth, and that the same shalbe made by the consent of your people as hath been accustumed.”]

“I graunte and promitte.”

The allusion to Edward the Confessor in the original oath, alongside the use of his crown in coronation ceremonies, emphasized dynastic continuity and evaded situating the claim of English kings to afier the Norman Conquest. The invocation of an Anglo-Saxon king, who was also a Catholic Saint, canonized in 1161, was a traditional reaffirmation of ancient principles of government by consent, coinciliar representation, and election in conjunction with the clerical estate. Manhood suffrage and a free parliament were believed to have originated in Saxon England. The change was retained by Mary. […] The excision of Edward the Confessor and the traditional bifurcation of the social body into two estates, clergy and people, reflected the revolution in religious politics which had taken place with the creation of the Supreme Headship.

[…] Mary was the first ever anointed female sovereign. The sword was a symbol of imperial rule, representing justice, but also kingly prowess and strength. Henry VII had girt himself. Mary was girt by Stephen Gardiner. The tacit acceptance of imperial claims in her oath was reinforced in the unprecedented nature of the crowning itself:

the byshop of wynchester and the duke of Norfolk brought unto her highnes iii corownes to wyt/ one kinge Edwards crowne the other the imperiall crowne of this realme of Englande the thyrd a very riche crowne the which was made purposefely for hir grace.

Mary was the first English monarch to be crowned with a triple crown and the first to wear the imperial crown which had been commissioned by Henry VIII, first mentioned in an inventory of 1521. The third crown was commissioned specifically by Mary, underlining that this appropriation of imperial iconography was entirely deliberate on her part).

The imagery of the triple crown orginated in the triple-tiered papal tiara which represented the universal, Catholic jurisdiction of the pope. It was appropriated by Charles V for his entry into Bologna to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1530. Neo-Roman ceremonial helmets were borne by pages during the ceremony, one of which was surmounted by a double crown, an advertisement of Charles’ claim to universal empire. The Habsburg mythology of 'universal monarchy’, in Gattinara’s words (cf. p. 17), was reiterated symbolically by the triple-crown of the Imperial Coronation. This gesture was explicitly contested by the powerful grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire, Ibrahim Pasha who as part of the Ottomans military campaign of 1532, commissioned a four-tiered ceremonial helmet-crown from Venice, for Suleyman the Magnificent’s triumphal march on Vienna. The self-conscious repudiation of Charles V’s claim through a form of symbolic competition made a counter-claim on SUleyman’s part to be “imperator del mondo”.'

Mary’s borrowing from Habsburg symbolism was an allusion to political afluliations, but also manifested more importantly her specific claim to exercise imperial authority in her own right. The message was disseminated on a European stage with the rapid publication in Rome of an account of the coronation, Coronatione de la serenissima Reina Maria d'Ingbilterra faltta II di primo d'Ottobre MD.Lffl (Rome: 1553) and then through the issue in Castile the following year of the Coronacion de la Inclita y Serenissima revna Maria de Inglaterra (Medina del Campo: March, 1554) to promote the marriage. The Castilian account designed to sell the marriage, described Mary as “de treynta y ocho afios: y hermosa sin par”, the tag applied to Oriana in AmadIs.

[…] After the anointing and crowning, mass was performed: “con mucha solemnidad estando siempre su magestad de rodillas con grande deuoccion y grandes seflales de religion”.’ The argument, which is fully developed later, that Mary’s reputation for piety was specifically cultivated in the context of international politics, is usefully supported by this fragment of evidence which appears only in the Castilian account of her coronation.

Piety was the queenly virtue par excellence. The image served to make her a more attractive prospect in the context of the Spanish marriage, holding out the possibility of reclaiming an important kingdom through a queen suitably disposed in religion.

Finally the assembled company did homage to Mary I. Gardiner on behalf of the spiritual lords swore: “I shailbe fathfull and trew.. I shall do and truly knowlige the servys of the landes which I cleme to holde of yow as in the right of youre churche as god shall helpe me”.

A representative of each rank of the temporal lords swore on behalf of their peers: “I N. become your lyege man of lyfe and lne and of all erthly worship and faith and al truth shal beare unto to you to lyue and dye with you agaynst all manner of foke so god helpe me and all halowes”.

Ecciesiastics acknowledged in their oath of allegiance that they held land mediately of the crown. The wording here was unchanged from the oath taken to Hemy VII. The church had never been recognised as possessing seisin or plenum dominium in its ecclesiastical properties in England. The peerage were bound to the monarch according to a neo-feudal allegiance, implied by the term 'liegeman’, and recognised their status as that of vassals of the sovereign.

After doing homage, they kissed her left cheek. Then Mary changed again and at 4pm she departed to Westminster for a banquet, “having in hir hande a cepter of golde, and in hir other hande a ball of golde, which she twirled and toumed in hir hande as she came homewarde”. At the feast Mary, Elizabeth, Gardiner, and Anne of Cleaves, all seated at one board, were served with over 312 dishes. A total of 7112 were offered to the company as a whole of which 4900 are described in the records as 'waste’.'”

Quoted from: SAMSON, Alexander Winton Seton.“The marriage of Philip of Habsburg and Mary Tudor and anti-Spanish sentiment in England : political economies and culture, 1553-1557″. pp. 43-54.

You may find it in this link: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30695717.pdf

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Replica of medal commemorating the restoration of England to Catholic Communion, and Mary I of England’s pregnancy 1554

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Mary had also decided on a grand public display rather than a private wedding, according to her prerogative, just as in times past a king could be married ‘prively or openly’. Although Judith M. Richards has argued that royal weddings in England tended to be private occasions and that, in contrast, ‘the procedures were very different’ for the unusual event of a regnant queen’s marriage, the choice of public or private ceremonies in fact depended on circumstances specific to each Tudor marriage. Henry VIII’s wedding to Catherine of Aragon in 1509 at Greenwich had been a quiet, speedy affair so that she could share his coronation; his marriage to Anne Boleyn had to be conducted secretly in 1533 because she was pregnant and the annulment of his previous marriage had not yet taken place. Henry’s nuptials with Jane Seymour had occurred shortly after Anne Boleyn was beheaded by the king’s order, and the obscene haste of the match likely called for some discretion at the wedding. Henry VIII’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, arrived on January 3, 1540, and was married three days later in a season of the year when the church forbade marriages, a fact that may have limited the festivities. The circumstances of his nuptials with Catherine Howard on July 28, 1540, echoed the unseemly haste of the Seymour wedding: Henry and Catherine were married only 18 days after his previous alliance was annulled and on the same day that Thomas Cromwell was beheaded. Mary would hardly have wanted to study these marriage ceremonies as exemplars.

The Tudors, however, were also capable of grand, extravagant weddings. Catherine of Aragon’s first marriage to Prince Arthur in 1501 had been a lavishly opulent, grandiose public affair within St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, with King Henry VII, his queen, Elizabeth, members of the royal court, and city dignitaries all in attendance. There had been a procession through the streets of London before the wedding and banqueting and a tournament after it; and the festivities, including dances, masques, and jousting, went on for a week. It is more likely that Mary I took her mother’s first wedding to Prince Arthur rather than her father’s marriages for her model. Whatever the inspiration, Mary I the city of Winchester provided a convenient meeting point and marriage site for Mary, journeying from London, and Philip, arriving from Southampton. The queen issued a proclamation on July 21 ordering that ‘all noble men and gentlemen, ladies and other apointed by her maiestie to attende upon her grace’ at the wedding ‘doo with all convenyent spede make their repaire to her grace cytie of Wynchester, there to give their attendance upon her’. Summoning the peers of the realm to witness this important ceremony turned it into the kind of magnificent public occasion that England had not witnessed for some years. In addition, the participation of England’s nobility, the country’s leaders, validated Mary’s choice of spouse and potentially created an aura of widespread support for the queen and her husband while overcoming the spectre of resistance to the Anglo-Spanish alliance.”

Sarah Duncan, Mary I

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

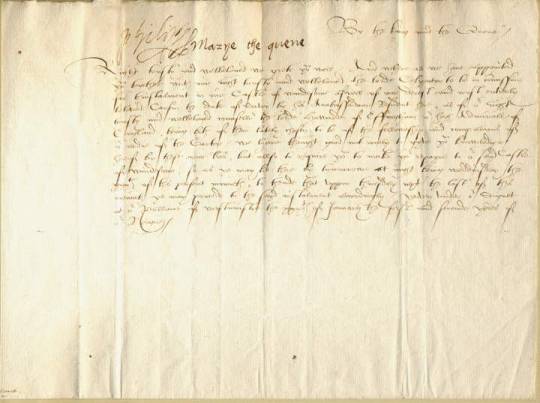

~Letter Signed by Mary Tudor and by Philip II (of Spain) as King of England to William, Baron Paget (1505/6-1603), 29 January 1555.~

“The letter orders Lord Paget and ‘Lord Clynton’ to attend at Windsor Castle as commissioners to oversee the installation of Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, and Lord Howard of Effingham 'high Admirall of England’ as members of the Order of the Garter.”

'Right trusty and welbeloved we grete you well. And where as we have appointed you together with our right trusty and welbeloved the lorde Clynton to be in com'ission for the instalment in our Castle of windesour as well of our derest and most entirely beloved Cousin the duke of savoy by his Ambassadour Resident here [i.e. as the duke’s proxy], as of our right trusty and welbeloved counselor the lorde Howarde of Effingham our high Admirall of England, being both of them lately chosen to be of the fellowship and companions of our order of the Garter. We have thought good not onely to gyve you knowledge hereof by these our l[ett]res, but allso to require you to make your repayre to our said Castle of windesour, for as ye may be there by tommorrow at nyht being weddeinsday the xxxth you may procede to the sayd instalment accordingly. Geven under our Signet at our Pallauce of westminstre the xxixth of January the first and seconde yeres of our Reignes. [1555]’

Link: https://www.manuscripts.co.uk/stock/26614.HTM

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stained glass window of Queen Mary I in the Chapel of Trinity College, Cambridge. The college was founded by Henry VIII in 1546. His daughter, Mary, granted Trinity monastic lands worth £370 a year in 1554. The building of the chapel commenced during Mary’s reign. The stained glass image of Mary is beside one of her father. The windows were commissioned in the nineteenth-century. The chapel was completed in 1567, during the reign of Elizabeth I (who is also represented in one of the windows).

The second is a nineteenth-century stained glass window depicting Queen Mary in the cloisters of Worcester Cathedral. Mary visited the Cathedral in 1526 aged ten-years-old, celebrating mass at the High Altar.

15 notes

·

View notes