Text

“One day there was an anonymous present sitting on my doorstep—Volume One of Capital by Karl Marx, in a brown paper bag. A joke? Serious? And who had sent it? I never found out. Late that night, naked in bed, I leafed through it. The beginning was impenetrable, I couldn’t understand it, but when I came to the part about the lives of the workers—the coal miners, the child laborers—I could feel myself suddenly breathing more slowly. How angry he was. Page after page. Then I turned back to an earlier section, and I came to a phrase that I’d heard before, a strange, upsetting, sort of ugly phrase: this was the section on “commodity fetishism,” “the fetishism of commodities.” I wanted to understand that weird-sounding phrase, but I could tell that, to understand it, your whole life would probably have to change. His explanation was very elusive. He used the example that people say, “Twenty yards of linen are worth two pounds.” People say that about every thing that it has a certain value. This is worth that. This coat, this sweater, this cup of coffee: each thing worth some quantity of money, or some number of other things—one coat, worth three sweaters, or so much money—as if that coat, suddenly appearing on the earth, contained somewhere inside itself an amount of value, like an inner soul, as if the coat were a fetish, a physical object that contains a living spirit. But what really determines the value of a coat? The coat’s price comes from its history, the history of all the people involved in making it and selling it and all the particular relationships they had. And if we buy the coat, we, too, form relationships with all those people, and yet we hide those relationships from our own awareness by pretending we live in a world where coats have no history but just fall down from heaven with prices marked inside. “I like this coat,” we say, “It’s not expensive,” as if that were a fact about the coat and not the end of a story about all the people who made it and sold it, “I like the pictures in this magazine.” A naked woman leans over a fence. A man buys a magazine and stares at her picture. The destinies of these two are linked. The man has paid the woman to take off her clothes, to lean over the fence. The photograph contains its history—the moment the woman unbuttoned her shirt, how she felt, what the photographer said. The price of the magazine is a code that describes the relationships between all these people—the woman, the man, the publisher, the photographer—who commanded, who obeyed. The cup of coffee contains the history of the peasants who picked the beans, how some of them fainted in the heat of the sun, some were beaten, some were kicked. For two days I could see the fetishism of commodities everywhere around me. It was a strange feeling. Then on the third day I lost it, it was gone, I couldn’t see it anymore.”

— Wallace Shawn, The Fever (1990)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Midway through Jamil Jan Kochai’s collection The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories, which maps generations of Afghan and Afghan American lives against over a century of entwined wars, sits what appears to be a résumé. Entitled “Occupational Hazards,” it meticulously records the everyday labors of an Afghan man: […] his “[d]uties included: leading sheep to the pastures”; from 1977–79, “gathering old English rifles” left over from the last war while being recruited into a new war; in 1980–81, “burying the tattered remnants of neighbors and friends and women and children and babies and cousins and nieces and nephews and a beloved half-sister”; […] becoming a refugee day-laborer in Peshawar, Pakistan; in 1984, becoming a refugee in Alabama, where he worked on an assembly line with other Asian migrants whom the white factory owner used to push out the local Black workforce; and so on. Dozens of events, from the traumatic to the mundane, are cataloged one by one in prose that is at once emotionless and overwhelming. […] Kochai interviewed his father for the résumé’s occupational trajectory […]. An Afghan shepherd […] is displaced by imperial wars and then, in the heart of empire, is conscripted into racialized domestic economies […]. [M]ethodically translating lived violence via a résumé, a bureaucratic form that quantifies labor in its most banal functionality, paradoxically realizes the spectacular breadth of war and how it organizes life’s possibilities. […]

—

In this collection, war is past, present, and plural. In Afghanistan, Kochai recounts the lives of Logaris and Kabulis, against the backdrop of the US occupation, still dealing with the detritus of previous wars - British, Soviet, and civil - including their shrines, mines, and memories. In the United States, Afghan Californians experience the diasporic conditions of war – state neglect of refugees combined with targeted surveillance – amid the coming-of-age of a second generation that must confront inherited traumas while struggling to build political solidarities with other displaced youth.

These 12 stories explore the reverberations between historical and psychic realities, invoking a ghostly practice of reading. Characters, living and dead, recur across the stories […]. Wars echo one another […]. Scenes and states mirror each other, with one story depicting Afghan bureaucracies that disavow military and police violence while another depicts US bureaucracies that deny social services to unemployed refugees. History itself is layered and unresolved […]. Kochai, who was born in a refugee camp in Peshawar, writes from the position of the Afghan diaspora […]. In August 2021, the US relegated Afghanistan to the past, declaring the “longest American war” over. Over for whom? one should ask. […] War, in other words, is not an event but a structure. […]

—

In Kochai’s collection, war is not the story; rather, war arranges the scenes and life possibilities […]. Kochai carefully puts war itself, and the warmakers, in the narrative background […].

This is a historically incisive narrative design for representing Afghanistan. Kochai challenges centuries of Western colonial discourses, from Rudyard Kipling to Rambo, that conflate Afghanistan with violence while erasing the international production of that violence as well as the social and conceptual worlds of Afghans themselves. Instead, this collection moves the reader across Afghans’ transcontinental, intergenerational, and multispirited social worlds – including through stories of migrations and returns, homes populated by the living and the martyred, language that enmeshes Dari, Pashto, and Northern California slang, as well as the occasional fantastical creature […].

—

Like Kochai’s debut novel 99 Nights in Logar (2019), this collection merges realism and the fantastic, oral and academic histories, Afghan folklore and Islamic texts, giving his fiction a dynamic relation to history. Each story is an experiment, and many of them are replete with surreal or magical elements […].

As in Ahmed Saadawi’s 2013 novel Frankenstein in Baghdad, a nightmarish sensorium collides with a postcolonial body politics […].

In a recent interview, Kochai said that writing about his family’s experiences of war has compelled him to explore “realms of the surreal or magical realism […] because the incidents themselves seem so unreal […]. [I]t takes years and decades to even come to terms with what had actually happened to them before their eyes.” He points not to a documentary dilemma but to an epistemological one. While some scholars have argued that fantastic genres like magical realism are often conflated with exoticized imaginaries of the Global South, others have defended the form’s critical possibilities for rendering complex realities and multiple modes of interpretation. Literary metaphors, whether magical or otherwise, are always imprecise; as Afghan poet Aria Aber puts it, “you flee into metaphor but you return / with another moth / flapping inside your throat.” […]

Kochai does not “escape” into the surreal or magical as fictions but as other ways of reckoning with war’s pasts ongoing in the present.

—

Text by: Najwa Mayer. “War Is a Structure: On Jamil Jan Kochai’s “The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories.”“ LA Review of Books (Online). 20 December 2022. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

"If I Forget Thee, Oh Earth" - By Arthur C. Clarke

x x x x x x x

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1990 - When developers and the town of Oka wanted to start building a golf course on stolen land that belonged to them and that contained a sacred grove and a burial ground, the Mohawk tribe around Kanehsatake, Quebec, rose up and occupied the area. The mayor of Oka sent in SWAT teams to make the construction possible.

After chasing off the police and construction workers, members of the tribe use a front-end loader that was left behind to build barricades from the abandoned police vehicles, blockading a highway. Ultimately the stand-off with the police and the Canadian army lasted 78 days.

From this great documentary: [Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance]

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

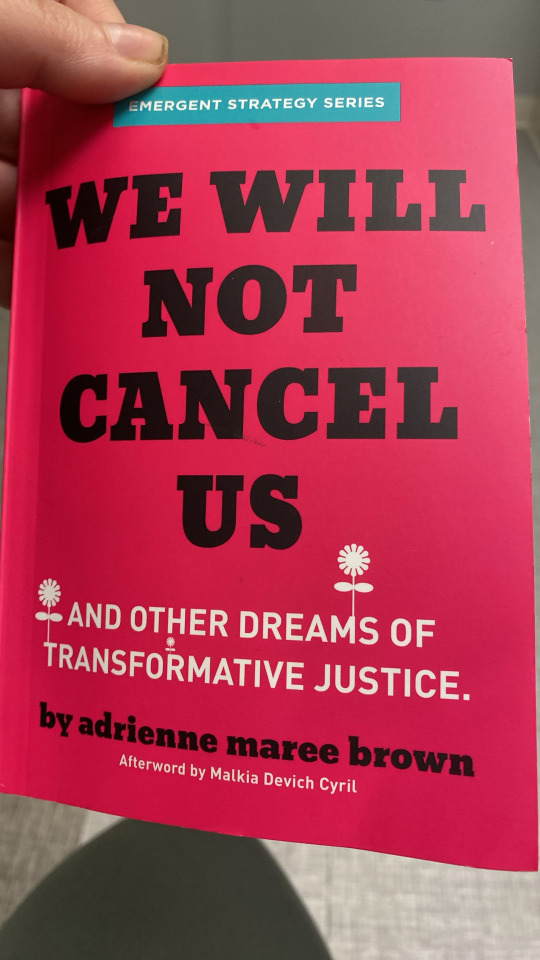

use, and i cannot stress this enough, thriftbooks

45K notes

·

View notes

Text

The day is taken by each thing and grows complete.

I go out and come in and go out again,

confused by a beauty that knows nothing of delay,

rushing like fire. All things move faster

than time and make a stillness thereby. My mind

leans back and smiles, having nothing to say.

Even at night I go out with a light and look

at the growing. I kneel and look at one thing

at a time. A white spider on a peony bud.

I have nothing to give, and make a poor servant,

but I can praise the spring. Praise this wildness

that does not heed the hour. The doe that does not

stop at dark but continues to grow all night long.

The beauty in every degree of flourishing. Violets

lift to the rain and the brook gets louder than ever.

The old German farmer is asleep and the flowers go on

opening. There are stars. Mint grows high. Leaves

bend in the sunlight as the rain continues to fall.

—Linda Gregg, “Praising Spring”

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you don't mind me asking, who is your favorite author or what are some books you really love? Your artwork and poems mean a lot to me and they feel filled with so much implied narrative. I'd love to know the stories that are close to your heart!

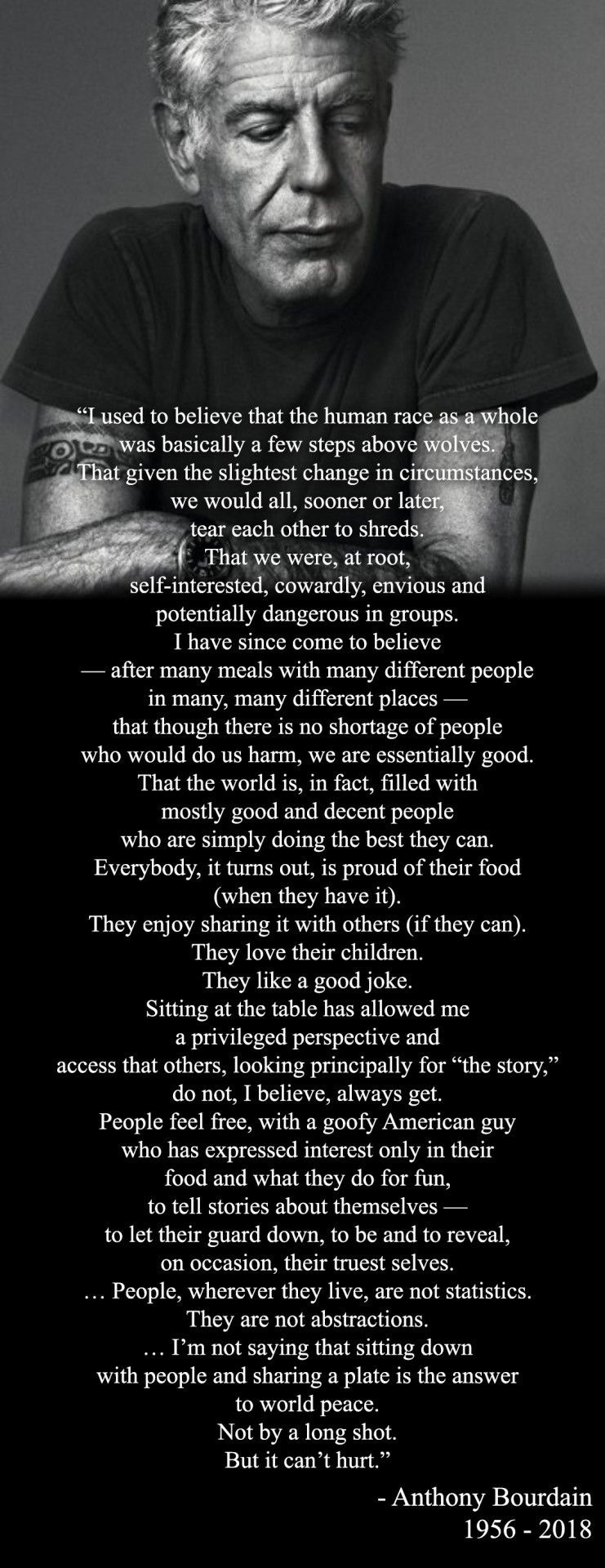

Aw this is a nice thing to ask. Cormac McCarthy is my favorite writer! For me his books have no peers. I recently finished The Crossing and it's my favorite of all though it had me crying miserably throughout. Beautiful, awful.

Some other books that I love are The Secret History by Donna Tartt, Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer, House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski, Watership Down by Richard Adams and The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson.

943 notes

·

View notes

Text

21 Love Poems: 10

by Adrienne Rich

Your dog, tranquil and innocent, dozes through

our cries, our murmured dawn conspiracies

our telephone calls. She knows—what can she know?

If in my human arrogance I claim to read

her eyes, I find there only my own animal thoughts:

that creatures must find each other for bodily comfort,

that voices of the psyche drive through the flesh

further than the dense brain could have foretold,

that the planetary nights are growing cold for those

on the same journey, who want to touch

one creature-traveler clear to the end;

that without tenderness, we are in hell.

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Close to the Knives is required reading. You've probably seen pictures of David Wojnarowicz wearing a jacket that says "IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A." But you need to read what he had to say about being homeless and desperate for a good night's sleep, fantasizing about bludgeoning abusers and oppressors to death, fucking in highway rest stops and piers, the crimes of the US both domestic and abroad, the dangerousness of 12 inch politicians on TV screens, and how he lived with AIDS before he died. You would learn something.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t think a lot of people really understand that ecosystems in North America were purposefully maintained and altered by Native people.

Like, we used to purposefully set fires in order to clear underbrush in forests, and to inhibit the growth of trees on the prairies. This land hasn’t existed in some primeval state for thousands of years. What Europeans saw when they came here was the result of -work-

101K notes

·

View notes

Text

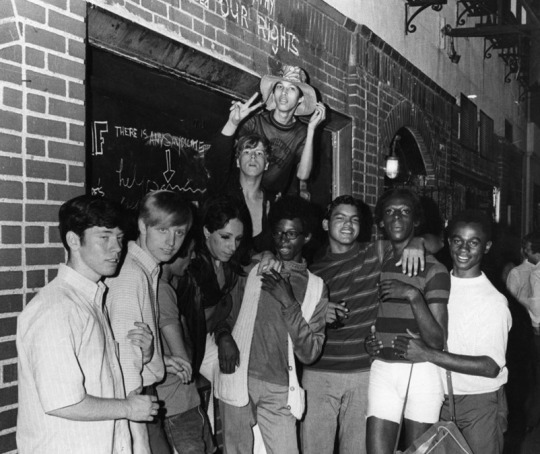

People celebrating outside the boarded-up Stonewall Inn following the raid-turned-revolt that took place over the weekend

June 29th 1969 | ph: Fred W. McDarrah

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

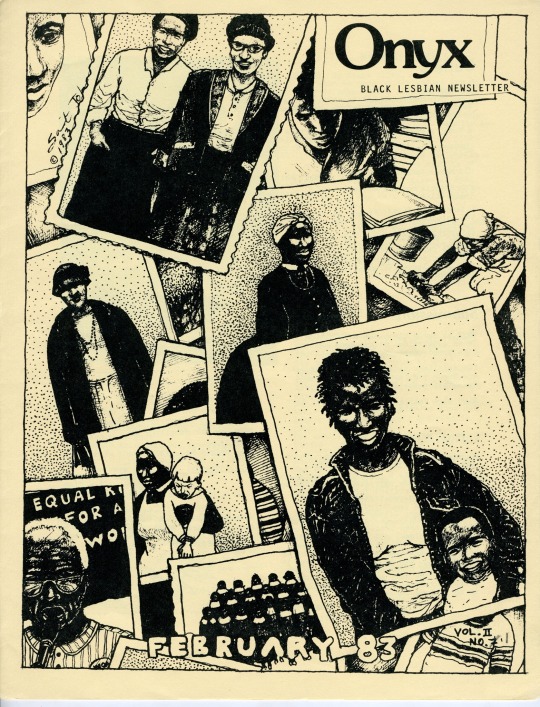

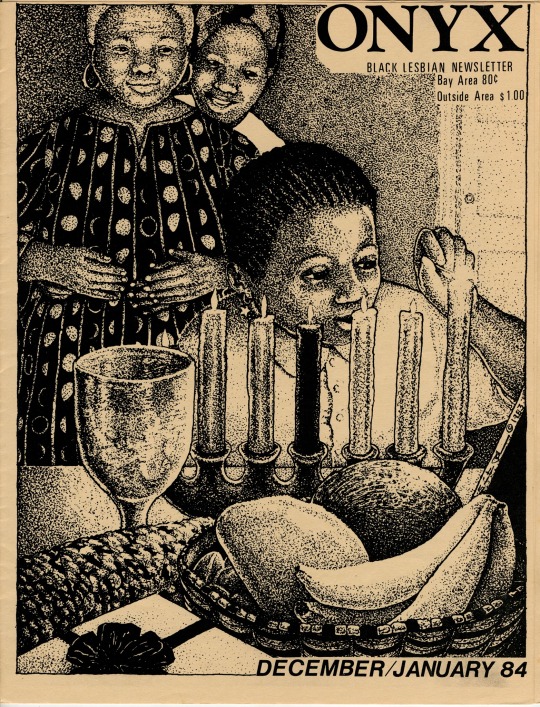

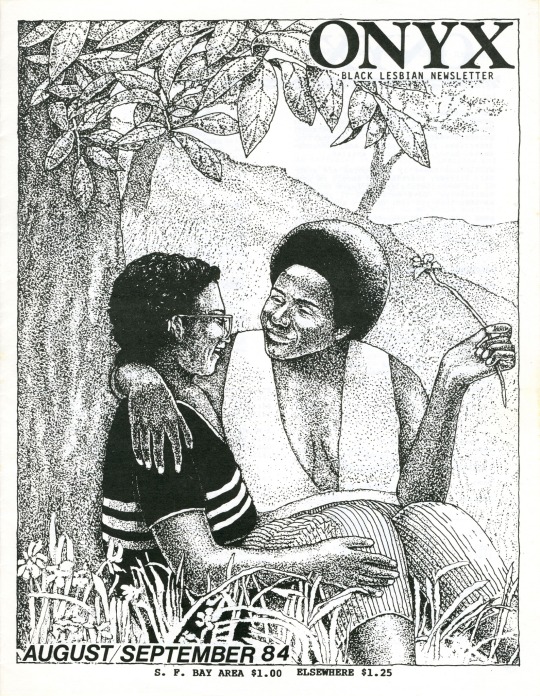

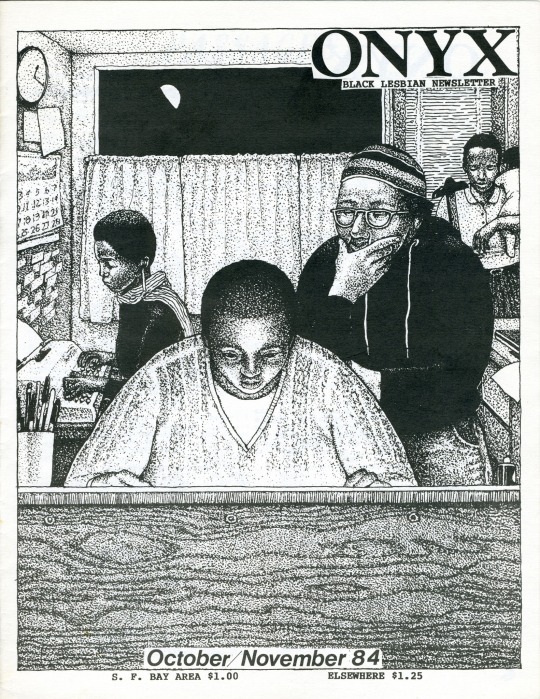

ONYX: Black Lesbian Newsletter was a bimonthly magazine focusing on Black lesbian life, published in the Bay Area from 1982 - 1984. All issues are available to read here.

3K notes

·

View notes