Text

Messages in Advertising

We are surrounded by advertising almost constantly through all mediums. They are in print newspapers and magazines, plastered on public transport and in buildings and on billboards, on websites and social media, on TV and radio. Ads can affect not just what products we buy, but how we see the world. Thus, it is important to investigate and be aware just what those affects are. The theories of cultural studies and symbolic interactionism examine the impact advertising has on us.

The theory of cultural studies, put forward by Stuart Hall, essentially posits that mass media helps enforce the dominant ideologies put forward by the upper class. Hall emphasized that these messages cannot be taken out of their context (which is why it is cultural studies and not media studies) because these messages derive meaning from the culture they are in. Furthermore, he stressed the importance of examining power imbalances and deconstructing them through the use of this theory. The purpose of cultural studies is to become aware of how media promotes the status quo so it can be resisted (Griffin, 2015, p. 340). Cultural studies speaks to all media, but advertising is one specific area filled with hegemony.

Symbolic interactionism is a theory of George Herbert Mead that postulates that people form their sense of identity through communicating with others (Griffin, 2015, p. 54). However, as Wood and Fixmer-Oraiz (2017) point out, “others do not communicate from strictly personal perspectives…their communications reflects the values and meanings of their culture” (p. 46). Therefore, the ideologies taught and sustained through mass media are perpetuated by people even in the absence of media. Furthermore, symbolic interactionism says that people act towards others based on the meanings they assign to them (Griffin, 2015, p. 55), so when the ideologies we learn become stereotypes and prejudiced assumptions, they can do real damage; for people with privilege, it can mean they feel their position of power is warranted or give them a negative view of those different from them, and for oppressed groups it can reinforce stereotyped roles and create a feeling of being “other” in their own society. Advertising is part of the socialization process that causes us to communicate cultural ideals that help shape our identity and view of others.

A recent advertisement that got a lot of attention was a Pepsi ad starring Kendall Jenner of Keeping Up With the Kardashians fame.

youtube

The ad blew up almost immediately on Twitter as well as being the object of several pointed late night sketches. The bulk of the backlash was focused on the racism and tone deafness of the ad. The premise of the commercial is a protest march à la Black Lives Matter, but the signs show no real cause for the march.

They say things like “peace” “love” and “join the conversation”, none of which put forth any real message, unlike the protests it is feigning to emulate. One of the key things the Black Lives Matter movement protests is police brutality—specifically, the murdering of black people without even a hint of justification (and the lack of repercussions for that). The movement is pointing out a major flaw in the system, but this Pepsi commercial does the opposite with its depiction of police: they are not in riot gear (as they are without fail at every BLM protest, without provocation) or even armed. They are depicted not just as nonthreatening, but as friends to be made, completely ignoring the systemic flaws in the United States’ police force. The idea that a Pepsi is all it takes to fix things trivializes a serious issue, as shown pointedly in this tweet from Bernice King, the daughter of Martin Luther King, Jr.

This clearly shows that the problem is much more complex than “just getting along” and how useless a Pepsi would be in a real situation of oppression. In addition, the person who befriends the police is Kendall Jenner—an extraordinarily privileged white woman. As cultural studies points out, it is important to examine power relationships—and this ad fails not only to depict the power imbalance between police and civilians, but also uses someone who is in reality the least in danger from police as the “brave soul” to unite them all. Jenner’s approach to the police feels like a gross mimicking of the photo of Iesha Evans standing up to police in Baton Rouge—unlike Jenner, her approach did not magically unite everyone, but instead got her arrested despite being utterly nonthreatening (Sidahmed, 2016).

This advertisement sends a “can’t we all just get along” message that overwrites decades of oppression and ignores the voices of oppressed people advocating for change. Through the lens of cultural studies, it is clear this ad reinforces the idea that police are not the problem. According to symbolic interactionism, as people have this belief confirmed in an ad, they share it and it can become a key part of our (white) American identities that police are utterly trustworthy and are not at fault for the issues surrounding them; this in turn can lead to viewing people, particularly people of color, who say otherwise as complaining about a nonissue, making it difficult for them to be taken seriously. Granted, this particular ad will probably not have that affect due to the heavy negative reactions it received that lead to its immediate removal, but it is indicative of a larger ideology enforced in many different ways. And of course, it only got that reaction because of the society we live in, which did not approve of the message being sent—as Hall points out, mass media does not exist in a vacuum, and the context of the ad (both what it was drawing from and how it was received) hugely impacted it.

On a slightly more subtle level, the ad also promotes the ideology behind capitalism. Of course, every advertisement does this on some level because they are trying to get people to do the intrinsically capitalistic thing of buying their product, but this ad in particular promotes those values. Like many ads, it shows those using the product as young, attractive, and happy, the implication clearly being that if you drink Pepsi, you align yourself with those people and become those things yourself. As Colbert (2017) points out on the Late Show, this is intentional in order to target a specific demographic—millennials.

But on a deeper level, it portrays consumerism as the solution to society’s ills; the answer the Black Lives Matter movement has been looking for was Pepsi all along! Even if it was not meant quite so literally, the message is still clear: buying products is what will unite us, solve our problems, and make us happy. And since capitalism and consumerism is the law of the land, this again shows Hall’s ideas to be correct—on some level, mass media is feeding us the same ideologies over and over to ensure we still believe them. The other layer to this is the exploitation of protesting and more specifically, Black Lives Matter. As explored above, this commercial appropriates the movement while simultaneously undermining the message. Pepsi is not showing protests because it wants to promote resistance—it is showing a march because they are “trendy” now, and thus are an opportunity to make money. The company feigns support of revolutionary ideologies, but undermines the real message and will only promote resistance for as long as it is profitable.

This Pepsi commercial is not the only racist ad out there, however. Only a few weeks ago, a Nivea ad came under fire for using the slogan “White is purity” and an old PlayStation ad resurfaced depicting a white person assaulting a black person (Kuchera, 2017).

These ads show that this recent Pepsi ad is not an anomaly; advertising is full of racist messages. Once again, it is critical to remember (for both consumers and marketing departments) that these advertisements exist in a cultural context. In a world without racial issues, a statement like “white is purity” might be innocuous, but here, in a time marked by the rise of neo-Nazis and white supremacists, it smacks of racism. Power relationships are also important, and the PlayStation ad draws a crystal clear image of white control over black bodies. Advertising like this plays into symbolic interactionism as well, enforcing a belief on some level of white superiority. As we communicate these beliefs to each other, it creates a sense of identity for both sides—those who belong, and those who do not.

Advertising, and mass media in general, seem to permeate every part of our lives. It is crucial that we are aware of the impact this has on us. Cultural studies tackles this issue head on, examining what role mass media plays in enforcing the status quo and how to resist. Symbolic interactionism highlights the importance and great influence our interactions have on our identity and view of the world. Both of these theories make it evident that paying attention to the messages advertisements are sending, both overt and covert, is essential for any change to occur.

References

0 notes

Text

References

For this essay.

BDisgusting. (2017, April 8). “Obey. Consume” [Twitter post]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/BDisgusting/status/850892691982430208

BerniceKing. (2017, April 5). “If only Daddy would have known about the power of #Pepsi” [Twitter post]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/BerniceKing/status/849656699464056832

Griffin, E., Ledbetter, A., & Sparks, G. (2015). A first look at communication theory: Ninth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

[Kendall and Kylie]. (2017, April 4). Kendall Jenner for Pepsi commercial. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/dA5Yq1DLSmQ

Kuchera, B. (2017, April 5). Why is everyone talking about a racist Sony ad that’s 10 years old? Retrieved from http://www.polygon.com/2017/4/5/15190396/sony-psp-ad-white-is-coming-pepsi-kendall-jenner

[The Late Show with Stephen Colbert]. (2017, April 6). Stephen takes on Kendall Jenner’s ‘attractive lives matter’ Pepsi ad. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/qDWlMi14quY

Sidahmed, Mazin. (2016, July 11). 'She was making her stand': image of Baton Rouge protester an instant classic. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jul/11/baton-rouge-protester-photo-iesha-evans

Wood, J. T., Fixmer-Oraiz, N. (2017). Gendered lives: Communication, gender, & culture, twelfth edition. Boston: Cengage Learning.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bibliography

Bibliography for essay found here

Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin Group, 2004. Print.

DiGiacomo, Frank. "'Hamilton's' Lin-Manuel Miranda on Finding Originality,

Racial Politics." The Hollywood Reporter. The Hollywood Reporter, 12

Aug. 2015. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.

Fox, Jesse David. "In the Room Where It Happens, Eight Times a

Week." Vulture. New York, 11 Jan. 2016. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

Goldsberry, Renée Elise. "Renée Elise Goldsberry on 'Hamilton'" Interview by

Christopher John Farley. Youtube. Wall Street Journal, 7 Mar. 2016. Web.

26 Apr. 2016.

Goldsberry, Renée Elise, Chris Jackson, Leslie Odom, Jr., Daveed Diggs, and

Phillipa Soo. "Charlie Rose Interviews the Cast of The Musical Hamilton."

Interview by Charlie Rose. PBS. New York City, New York, 1 Apr. 2016.

Television.

Gibbs, Constance. "How the Hero of Hamilton the Musical Is a Woman."The

Mary Sue. The Mary Sue, LLC, 16 Nov. 2015. Web. 06 May 2016.

Kail, Thomas, and Lin-Manuel Miranda. "'Hamilton'" Interview by Charlie

Rose. Charlie Rose. PBS, 21 Apr. 2015. Web. 2 May 2016.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel. "A Conversation with Lin-Manuel Miranda." Interview by

Dominique Gerard. Youtube. Montclair Kimberley Academy, 9 Mar. 2016.

Web. 1 May 2016.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel. "Charlie Rose Interviews Lin Manuel Miranda from The

Richard Rodgers Theatre." Interview by Charlie Rose. PBS. New York City,

New York, 12 Apr. 2016. Television.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel. "Emma Watson Interviews Lin-Manuel Miranda for

HeForShe Arts Week." Interview by Emma Watson. Youtube. Totally

Emma Watson, 17 Mar. 2016. Web. 30 Apr. 2016.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel, and Jeremy McCarter. Hamilton The Revolution. N.p.:

Grand Central Pub, 2016. Print.

Morris, Cass. "#YayHamlet: What Shakespeare and Broadway’s Biggest Hit

Have to Do with Each Other." ASC Education. WordPress, 16 Feb. 2016.

Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

Original Broadway Cast. Hamilton. Atlantic Records, 2015. MP3.

0 notes

Text

The Women of Hamilton

Every kid in the United States has sat through history class after history class learning about the American Revolution and the founding of our country. A place one would not expect to sit through this story is on Broadway, but that is exactly where the tale is most at home. The new musical Hamilton, written by Lin-Manuel Miranda, took Broadway by storm when it debuted at the Richard Rodgers Theatre in August of 2015, and it has only become more famous since then. The musical weaves modern music (hip hop and R&B) with the life story of Alexander Hamilton. Likewise, it also combines the story and people we know with details and figures we may never have heard of before—most notably, the three most impactful women of Hamilton’s life. The hit Broadway musical Hamilton shows how women like Eliza Schuyler Hamilton, Angelica Schuyler Church, and Maria Reynolds impacted the events of their own time period, their place in our history, and how this is applicable to women today. All three women influenced Alexander Hamilton’s life and left their marks on both him and American history.

Eliza, Angelica, and Maria are all real historical people, though they do not often show up in textbooks. The musical is largely faithful to who these women were, but Miranda did take some creative liberties, so it is important to distinguish between the historical figures and the characters in the show. Angelica and Eliza were the two eldest daughters of General Philip Schuyler, a wealthy revolutionary and member of the Continental Congress. Eliza was the only one of her five sisters not to elope; Angelica had already run away with John Barker Church by the time she met Hamilton. Eliza was well-liked by everyone, described as “a cheerful, modest soul, blessed with gumption” (Chernow 131). Though reserved and gentle, she had a reputation for being full of spunk and strong will. Throughout her life she proved to be kind, loyal, and self-effacing. She and Alexander met during the Revolutionary War, in February of 1780; they fell in love instantly and decided to be married just over a month later (Chernow 132). Despite Alexander’s other suspected love interests and confirmed affair, it is clear from their letters he loved her, and she him.

Eliza outlived her husband by fifty years, and spent those decades doing charity work and preserving Alexander’s legacy. Chernow devotes the entire last chapter of Alexander’s biography to these accomplishments. He points out that one of her greatest charitable accomplishments was the co-founding of the New York Orphan Asylum Society, the first private orphanage in the state. She held the position of deputy director from its founding in 1806 until 1821, when she rose to first directress and “oversaw every aspect of the orphanage work” for the next twenty-seven years (Chernow 728). The orphanage still exists today in the form of the Graham Windham organization. Chernow also shares how in 1818, Eliza obtained a charter for the Hamilton Free School, the first educational facility in Washington Heights, and also aided Dolley Madison in raising funds for the Washington Monument.

Eliza likewise worked diligently for the fifty years after Alexander’s death to ensure he would be remembered. She traveled to collect letters and documents of his work, interview his peers, and obtain mementos of his life, tasking her children with writing the thorough biography of their father’s life that none of his contemporaries would author (Chernow 727). Without Eliza’s efforts, many of Alexander’s accomplishments would have been forgotten forever.

Angelica, in contrast to Eliza’s quiet modesty, was outgoing and ambitious. She loved to discuss politics and books, emanated sophistication and femininity, and captured the attention of many men. She lived in Europe for over a decade with her husband, and was “one of the few American women of her generation as comfortable in a European drawing room as in a Hudson River parlor” (Chernow 133). Her intelligence and charm reveals itself in her social circle; Angelica befriended and exchanged letters with men such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Marquis de Lafayette, and many other influential politicians—and most of all, Alexander Hamilton himself. In many ways, Angelica was much more Alexander’s counterpart than Eliza, and “the attraction between Hamilton and Angelica was so potent and obvious that many people assumed they were lovers” (Chernow 133). They remained close throughout Alexander’s life, but it is unclear whether they ever had an affair. Lin-Manuel Miranda described the two as “intellectual soulmates”; Reneé Elise Goldsberry, who plays Angelica in Hamilton, defines their relationship as having “an emotional affair,” but there is no way of knowing if it was ever consummated. Goldsberry firmly believes that Angelica could have been president if that had been possible for women at the time. Possessing both vivacious brilliance and great social aptitude, Angelica Schuyler Church was one of the most influential founding mothers of the United States.

Maria Reynolds enters the history books at the age of twenty-three in 1791 when she first met Alexander Hamilton. The record of their relationship comes from Alexander’s own pen, as he released the infamous Reynolds Pamphlet detailing his torrid affair six years later in 1797. Maria approached Alexander at his home and told him her husband, James Reynolds, abandoned her for another woman, leaving her destitute. He had a weakness for women in distress and agreed to bring money to her home that evening. After he delivered it to her “some conversation ensued from which it was quickly apparent that other than pecuniary consolation would be acceptable.” This encounter initiated the two-year long affair that marred Alexander’s political career. Not long after the affair began Maria informed him she had reconciled with her husband, but their relationship continued—Maria maintained his sympathy by telling him her husband abused her—supposedly without James’s knowledge. Months later Maria wrote Alexander, telling him her husband had discovered the affair. James used this information to blackmail Alexander (while allowing the affair to continue) and extorted over one thousand dollars from him. It is unclear whether Maria was in on the scam from the beginning or had been drawn in by her husband later on, but in either case, it seems likely she did develop romantic feelings for him given that “Hamilton must have seemed elegant, charming, and godlike compared to her vulgarian husband” (Chernow 366). Maria had dabbled in prostitution before with her husband’s knowledge, so it is probable that the entire affair was a premeditated con. Her passionate letters to Alexander often verged on hysteria, indicating Maria’s emotional instability; she hated her husband so “she may have nourished fantasies that Hamilton would rescue her” despite the fact he was her victim (Chernow 367). Eventually, realizing the threat it posed to his career, Alexander ended the affair, and Maria later divorced James.

History knows little of Maria Reynolds’s life outside of this affair. This lack of information is true of Eliza and Angelica too; as Miranda puts it, “there’s not a definitive, Pulitzer-winning Schuyler sisters biography.” Women have been erased from history for centuries: from figures we know existed but have little knowledge of, to work credited only to “Anonymous,” to women who had to publish under a male pseudonym. Hamilton recognizes these historical women so often overlooked and shines the spotlight on them. Goldsberry points out that “we know the Founding Fathers but the mothers are a mystery.” Few students ever hear about these women at all; society perpetuates male-dominated history by failing to showcase these women. During the Revolutionary War era, the strongly patriarchal society relegated women to the sidelines, and even in modern times, history keeps them there. Chernow notes that Eliza “has languished in virtually complete historical obscurity” and “lack[ed] any identity other than that of Hamilton’s widow” despite her many accomplishments (Chernow 728). What makes Hamilton’s portrayal of Eliza, Angelica, and Maria so important is that it has never been done before. They are not background characters and love interests—they are important figures in their own right, as valuable and complex as any man on the stage. At long last, these women have been given a voice, not just in history, but in pop culture as well.

Eliza, Angelica, and Maria are not the only women on stage, however. The ensemble, almost omnipresent, is comprised of men and women. Most Broadway shows have a gender divide in the chorus: in Les Misérables the men are prisoners and the women are prostitutes, in The Pirates of Penzance the men are pirates and the women are refined ladies. Hamilton abolishes this divide; whenever the ensemble is onstage, the entire ensemble is present. Even in military scenes, a traditionally male space, women are singing about the battle as well—not from the sidelines, but in the midst of the action. This casting both gives women a voice in history and breaks down traditional gender roles that perpetuate every part of culture. The parts are cast based on ability rather than gender, for both ensemble and character roles. Miranda said he is open to making casting genderblind, so women could play the lead male roles. Hamilton allows women to be a part of history so long denied to them.

The inclusion of women is not the only thing that makes Hamilton stand out on Broadway, however. The musical has drawn attention for its explicit casting of people of color and for the musical styles used in show (primarily hip-hop, rap, and R&B). Both of these artistic choices are unusual for Broadway, but are particularly revolutionary in a musical about the white Founding Fathers of the United States. For Miranda, using hip-hop to tell this story was an obvious choice; not only is it the music he grew up with, but

It felt to me the quintessential hip-hop narrative. This is someone who grew

up in hard times and wrote his way out of his circumstances, wrote his way

towards a better life and that is the hip-hop narrative from the South Bronx

in the 70’s to today… this is a fundamental hip-hop story.

Beyond that symbolic level, hip-hop is not used as a gimmick, it is simply how the characters talk in this world. Hamilton is “the story of America then, told by America now.” Part of “America now” is hip-hop music. Hamilton pulls the Founding Fathers—figures viewed only as dusty old paintings—and brings them into the present, making this history accessible and enjoyable. This sentiment also explains why the actors are all people of color: “America now” is vibrantly diverse, and particularly as Alexander’s story is that of an immigrant, it only makes sense to reflect diversity in this portrayal of America. In addition, hip-hop is traditionally the music of people of color, making them the most appropriate people to cast to perform it.

Featuring hip-hop and actors of color in Hamilton has a profound effect on the view of history. For centuries, history was a white narrative; like women, people of color have always been pushed aside, and their only role was as the subordinate class. Featuring them as the founders of the country is a reminder to everyone that, as Miranda explains, “the story of the creation of this country is our story too.” By featuring people of color in these roles it allows them to reclaim this history that had hitherto only left a legacy of slavery and oppression. Many of the actors involved have expressed how they feel a sense of ownership of their history, something they previously felt was not for them. Daveed Diggs, who plays Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson, said working on Hamilton was “the only time I’ve ever felt particularly American” and that the musical gives value to everyone, no matter who they are. Hamilton does not shy away from who the founders were: when Jefferson makes his first appearance, he is being catered to on all sides by his slaves. Rather it emphasizes that all of United States’ history, good and bad, belongs to everyone.

One of the major themes of Hamilton is there is no way to fully control one’s place in history. All the characters are acutely aware that they are making history and often ponder how their actions will be regarded in a few centuries. Some of the repeated lyrical themes are “history has its eyes on you,” “who lives, who dies, who tells your story,” and the concept of “legacy.” The show contains constant references to “tomorrow” and “someday,” and the characters often celebrate how “lucky we are to be alive right now” because “history is happening” in this moment. Everyone knows their own significance in a greater historical narrative. Alexander announces people shouldn’t be “shocked when your history book mentions me,” already knowing he will have historical significance, though he only 19 years old at the time. He exemplifies many of the younger characters who are excited to leave their mark, while others, like George Washington, are haunted by the responsibility of making history. They can control their own actions and forge a legacy, but ultimately history’s version of them is beyond their control.

History in Hamilton is not a static narrative, but a living, breathing organism for them to engage with. The ensemble represents this force; the singers do not just back up the lead, but act as a proxy for the audience, yelling “No!” when Alexander fails to resist Maria Reynold’s temptation, whispering “history has its eyes on you” as characters make key choices. They are a constant presence, watching these great figures’ every move and holding them accountable, just as history does. The audience itself represents history, for they watch and judge centuries later. This emphasis on history and legacy constitutes a sort of constant fourth wall break in the musical; while these characters live in their time period, their unrealistic awareness of their greater historical narrative reminds the viewers of the difference between events as they happen and how history interprets them. For instance, Aaron Burr works his entire life to become an important politician, seeking to be in “the room where it happens.” But after he shoots Alexander in their duel, he realizes how “history obliterates” and that despite all of his accomplishments, history will only ever cast him as the villain to Hamilton’s hero. History is unforgiving—there are no do-overs and few second chances because history sees it all. This is symbolically highlighted by the staging of Hamilton, which has balconies outlining the stage. Often, characters not in a scene will be present on these balconies watching the action, underlining the idea that someone is always watching. Who is watching is just as important, because the musical emphasizes the question of “who tells your story?” Their legacy and place in history is influenced as much by who recounts their actions as by the actions themselves. The emphasis on history’s metanarrative in Hamilton highlights how subjective history is and how each story is created.

Eliza Schuyler Hamilton is, of all the characters, the most aware of this historical narrative. She is conscious of both her place in the narrative and how her husband’s story will be told. Eliza has an interesting arc in which she chooses her own place in Alexander’s story. In “That Would Be Enough” she begs him to let her “be a part of the narrative/in the story they will write someday.” She remains involved until after Alexander publishes the Reynolds Pamphlet detailing his affair to the public, when in “Burn” she declares that she is “erasing herself from the narrative.” From that point on, Eliza is present onstage but rarely speaks, until the final song of the musical which takes place after Alexander’s death. In “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story?” the answer to the titular question is ultimately “Eliza.” She declares that she “put herself back in the narrative” to preserve Alexander’s legacy. This arc allows Eliza to take control of her own story—significant for a woman in that time period—for she will not sit by while Alexander seeks glory by himself. She is supportive, not wanting the limelight, but seeking to be part of his story instead of a mere spectator. Alexander, while he loves her, consistently makes politics his priority over everything else. Eliza repeatedly asks if she is enough for him, and the answer is no. Just before asking to be included in the narrative in “That Would Be Enough,” Eliza tells Alexander that a legacy is unnecessary. Eliza is content to have a family, but while Alexander is happy with her, he has a passionate ambition that cannot be contained; thus, throughout his life, Eliza and his family come second to his work. Despite this, they have a loving relationship.

Eliza appears many times in Alexander’s timeline, usually attempting to convince him that family should be enough to make him happy. The next key moment for her metanarrative is after a chaotic, raucous song in which Alexander publishes the Reynolds Pamphlet and destroys his career, when the music abruptly drops to a quiet melody for “Burn.” This song features Eliza as she reacts to the affair and her husband publicizing it. She expresses her anger and pain while she burns all of their letters to remove all record of her reaction. “Burn” is the only song in Hamilton with only one person onstage; every other song has either multiple characters or the ensemble (usually both). But in “Burn,” Eliza is the only person singing, and no one is there to watch her; history no longer has its eyes on her because she made herself invisible. The entire point of the song is not just to show how the affair hurt her, but to establish Eliza’s power in making her own choices. There is a gap in history: there is no record of her reaction to the affair or the pamphlet. Hamilton takes this void and uses it to give a woman a voice. Instead of a simple explanation that Eliza’s reaction is unknown, or a few bars about her being upset, she gets an entire solo song to not only express her feelings, but show that her disappearance is her own choice. History did not erase her; she erased herself. Eliza used history’s limitations against it, making “future historians wonder/how Eliza reacted” in the aftermath of the Reynolds Affair. Instead of being just another woman lost to history, Hamilton gives Eliza’s disappearance a purpose, turning her from victim to the hero of her story.

From this point until the last song of the show, Eliza is largely vacant from the story. She is onstage for several of the songs between “Burn” and “Who Lives…” but has very few lines, and though before Eliza’s focalization was frequently internal, for this section of the musical it is entirely external. Though the audience can see her actions, Eliza’s thought processes and motivations are invisible, symbolizing how through taking herself out of the narrative, she left history in the dark. In “It’s Quiet Uptown,” while she and Alexander mourn their son’s death, that she finally forgives her husband, but there is no indication of how she got to that point. She only has one line in the song.

The next song Eliza appears in is “Best of Wives and Best of Women,” and it is the last song she sings in while Alexander is still alive. It is barely a song at all at only 47 seconds, but the love communicated in that time is profound. The song is based on the last letter Alexander wrote to Eliza before the duel, set to the same melody as “It’s Quiet Uptown” to evoke memories of their reconciliation and hinting at the enormous loss about to take place. Eliza asks him to come back to bed—significant because in “Burn” she tells him “you forfeit the place in our bed”—and tells him “that would be enough,” echoing her earlier pleas to be a part of his life in the song of the same name. This song affirms Eliza and Alexander’s love for each other, an important end to their relationship’s arc and the basis for Eliza’s loyalty to him after his death.

The final song of Hamilton works as an epilogue. Alexander has died and “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story?” explains what happened after while further exploring the question of legacy threaded throughout the musical. Eliza, who lived fifty more years after Alexander’s death, uses the time to put herself back in the narrative and make a difference. “Time” is a repeated theme in Hamilton from the first song, where the ensemble proclaims that Alexander “never learned to take [his] time” to the Act 1 closer that repeatedly asks him why he writes like he’s “running out of time” (a phrase oft reiterated in the show). During Alexander’s death monologue, he worries about his legacy and mentions time twice; once to recognize that “I’m running out of time, I’m running and my time’s up” and the other, directed at Eliza, to tell her to take her time. And she does. In the finale, “time” is repeated by the ensemble throughout, highlighting its importance. Eliza recognizes the blessing of time she has been given and uses it not only to honor Alexander’s legacy, but to do the things he would have done if he had still been alive. The song alludes to her efforts to raise money for the Washington Monument, her support of the abolition of slavery, the founding of the orphanage, and her commitment to telling his story. After all this, Eliza asks desperately: “and when my time is up? Have I done enough? Will they tell your story?” Once again, her focalization is internal as Eliza reinserts herself into history.

The finale, while not unprecedented, is unusual for Broadway, since it does not include the titular character. However, this is because “the sneak attack of the show is that it is Eliza’s story every bit as it is Hamilton’s story.” Though Aaron Burr narrates the musical, it is ultimately Eliza who tells Alexander’s story; his narrative is cradled by her own. Eliza’s story arc is key because it gives her the power to tell her own story and determine her own fate. She chooses whether or not to be a part of the story and in the end chose not only to be a part of the historical narrative, but also to “make her life so significant” and make her abundance of time count for something. Eliza’s role in the musical is not to prop up Alexander. Her character and story are unique and important to the overall narrative.

Eliza’s voice in the musical is very distinctive. She is one of the few characters who does not rap, because “Eliza is all about time”; rap expresses many ideas very quickly, while singing takes much longer to articulate a simple idea. She sings because she has more time than any other character in the show, and thus can take her time in saying what she needs to. Eliza is presented as a natural narrator in the way she sings throughout the musical, foreshadowing her ultimate role as the storyteller of her husband’s life and legacy. There is great parallelism in her songs, both internally and across the show. For instance, in “Helpless,” which recounts how she and Alexander met, the verses take similar courses and repeat several of the same lines. Both verses contain the phrases “as we/you wine and dine,” “my sister/father made their way across the room to you,” “thinkin’ I’m/we’re through,” and “you turn back to me…and I’m helpless!” Both verses track her feelings, which go on a similar path: anticipation to admiration to anxiety to sudden relief and an overwhelming realization of being in love. Eliza’s parallels extend across Hamilton. Her thread in and out of “the narrative” is a key parallel all through the show, giving a sense of Eliza as “someone who weaves the narrative even as she’s living it.” Eliza’s rhetoric throughout the show hints at aspects of her character—her wealth of time and role as a storyteller—finally affirmed in the final song.

Angelica’s narrative in Hamilton is that of a star-crossed lover, but she is simultaneously celebrated as a brilliant, passionate woman. Her first appearance is in “The Schuyler Sisters” when she, Eliza, and their younger sister Peggy sneak into downtown New York City to listen to the students speak. She announces she is searching for “a mind at work” and when Aaron Burr makes a pass at her, she turns him down telling him “Burr, you disgust me.” She also raps about reading political works and explains that while they “want a revolution, I want a revelation!” She concludes by declaring that when she meets Thomas Jefferson, she’ll “compel him to include women in the sequel!” Angelica is unafraid to espouse her views or reject a man; she is not a pretty prize to be won, but an intellectual with deep political opinions. Later, her tragic love story is introduced, but she is firmly established as a strong and independent woman before romance becomes important, assuring her status as a well-rounded character not solely used for love and drama.

When her love story with Alexander is introduced in “Satisfied,” Angelica is not reduced to a woman pining over a man. While she yearns to be with him, the song only reinforces her fierce intelligence and also emphasizes her love for Eliza. In this big number, “Satisfied,” Angelica is giving the toast at Eliza and Alexander’s wedding, but rewinds time to recount her perspective of when she and Eliza met Alexander for the first time. Lines of dialogue are interspersed with her introspective raps as she describes what her thought processes were in the moment. She falls for Alexander instantly, realizing that they are intellectual equals with similar views, and he is very handsome. She spends the rest of the song breaking down why she cannot be with him in a heartbreaking series of complex raps, the key reason being that Eliza loves him, and she always puts Eliza ahead of herself. It also introduces the idea of satisfaction that runs throughout the musical; neither of them will ever be satisfied, either in love (because they are apart) or in life (because they have great ambition).

Angelica does not appear again until the Act 1 finale, “Nonstop,” when she is leaving for England with her husband. Historically, she was married before she ever met Alexander, but the musical pushes back her own marriage to more easily narrate her almost-romance with him. Alexander is called to duty as Washington’s treasury secretary and is eager to serve, ignoring Eliza’s pleas to stay home with his family. While Eliza reiterates her key word “helpless”—reinforcing her love and her inability to make her husband put his family first—Angelica chimes in with “he will never be satisfied,” both reiterating that his ambitions are insatiable and foreshadowing his future affair.

Angelica shows up again in “Take a Break,” a song that showcases once again Alexander’s prioritization of work over his family. The song contains correspondence between Angelica and Alexander, writing letters about politics, literature, and with hints at their romantic feelings for each other. Mixing the three keeps Angelica from being relegated to a mere love interest, for it reiterates that she is Alexander’s equal and that intelligence is one of her key traits. Angelica comes to visit the Hamiltons for their summer vacation, but Alexander opts to stay home for work, yet another example of choosing ambition before family.

It is not until Alexander publishes “The Reynolds Pamphlet” that Angelica reappears. She comes from London during the chaos of his downfall, and he is grateful to see her, someone who “understands what I’m struggling here to do.” But she rejects him; she is here to support Eliza. This twist in their “star-crossed lovers” narrative is imperative to Angelica’s character. She is not blinded by love, but loyal to her family. These types of narratives frequently end in death or eternal separation, and rarely in a chosen rejection. Angelica bucks the traditional “star-crossed lovers” narrative because she is more than Alexander’s romantic interest: she is a sister. Her part in the song, spent lecturing Alexander on his horrible choice, end with her trademark phrase: “You could never be satisfied/God, I hope you’re satisfied.” Their lack of satisfaction originated as a bond they shared, but eventually it divides them, because Angelica puts Eliza before Alexander.

Angelica’s final appearance is in the finale. She introduces the idea of Alexander’s lost legacy, because “every other Founding Father’s story gets told/every other Founding Father gets to grow old.” She still loves him—and according to the previous song, both she and Eliza were by his side when he died—despite his affair. However, her loyalty to Eliza never wavers. Eliza relies on Angelica as she grows older, and while she is still alive they tell Alexander’s story together. When she dies, she is buried in the Trinity Church cemetery, “near Alexander but not with him, for eternity” (Miranda 281). This ending underscores Angelica’s role in the show one final time: always in love with Alexander, never able to have him, and supporting her sister above all until the very end. Angelica’s arc emphasizes her value, giving her depth as an intelligent, passionate woman who is loving and supportive of both Alexander and Eliza, but her loyalty never wavers from her sister.

While almost all of the men in Hamilton rap, of the three women, only Angelica does any rapping. Not only does Angelica rap, but her lyrics are “some of the most intricate” Miranda has ever written, so much so that even he cannot rap them. He describes them as “the HARDEST BARS IN THE SHOW” and “Satisfied” as “the most ambitious tune in this show” (Miranda 79-80). The goal of giving Angelica these complicated rhymes is not to show off, but to demonstrate her intelligence and that her mind runs at that speed all the time. She has impressive raps in all her songs, but “Satisfied” showcases not only her rapping abilities, but her characterization as well. She is attracted to Alexander from the moment she meets him but in less than ten lines of dialogue Angelica can already see through him. She immediately perceives that he is her intellectual equal, deduces that he is poor, and makes the decision to introduce him to Eliza despite her own feelings. She explains this in her own words, but the complexity of her language reinforces that she “read Hamilton the moment she saw him, but it didn’t stop her from falling in love with him, and didn’t stop her calculating in a moment to yield to her sister’s love for him” (Miranda 79). Her flashback begins with this rap:

I remember that night, I just might

Regret that night for the rest of my days

I remember those soldier boys

Tripping over themselves to win our praise

I remember that dreamlike candlelight

Like a dream that you can’t quite place

But Alexander, I’ll never forget the first

Time I saw your face

I have never been the same

Intelligent eyes in a hunger-pang frame

And when you said “Hi,” I forgot my dang name

Set my heart aflame, ev’ry part aflame, this is not a game.

Cass Morris, writer on one of the American Shakespeare Center’s education blogs, identifies various kinds of repetition throughout this passage. First, the repetition of “I remember” focuses the lines, establishing the move into the past as Angelica remembers when she met Alexander. The repeated “that night” in the first two lines is an example of mesodiplosis (repetition of words in the middle of a line); then there is antimetabole (an internal ABBA structure) with “that dreamlike candlelight like a dream.” The last line contains epistrophe (phrases with the same ending word) with the repetition of “aflame,” and all through this passage are examples of antithesis (contrasting of dissimilar words) with the juxtaposition of past and present tense, such as past tense “I forgot my dang name” followed by ambiguous tense “set my heart aflame” and ending with present tense “this is not a game.” Besides the repetitions and play with tenses, there are internal and end rhymes throughout the verse. The result is a sophisticated rap that weaves “in and out of reality, in and out of memory, in and out of what was and what could have been.” This style accentuates Angelica’s retrospective point of view and the complexity of her thought process.

At the start of her introspection, Angelica is thrilled to find that Hamilton is “at [her] level” and wonders “what the hell is the catch?” only to realize eleven lines later that he is poor, which launches her into a deconstruction of why they cannot be together. She isolates three decisive “fundamental truths” that make her decide to give him up. The first two are due to her identity as a Schuyler; her role as the oldest daughter is to marry wealthy, and her own wealth makes her an obvious target for the lower-class Alexander. Through both of these reasons, however, she makes clear that she still loves him, saying “that doesn’t mean I want him any less” and “nice going, Angelica, he was right/[without him] you will never be satisfied.” The music and underlying beat during the raps of these two reasons is erratic, but during the third reason, the music is steady, driven, and purposeful; her raps, instead of being flashy and unpredictably intricate, are firmly on the beat. This change symbolizes the core truth she cannot excuse and what ultimately motivates her to give up Alexander. Her third reason is that she can see Eliza loves him, because she saw that sister’s face is “helpless.” The other reasons are compelling, but this alone is enough to sacrifice her own happiness, for she explains, “I know my sister like I know my own mind/You will never find anyone as trusting or as kind.” Not only does Angelica give up a relationship with Alexander, she also introduces him to Eliza so they can be together, though it pains her to do so. Angelica’s love for Eliza trumps her love for Alexander, beginning a theme that lasts the entire musical.

The other most profound example of this theme is during “The Reynolds Pamphlet” when Angelica rejects Alexander to stand by Eliza after his sex scandal. She reiterates and adds to her earlier proclamation, resolutely showing that Eliza is her primary concern:

I know my sister like I know my own mind,

You will never find anyone as trusting or as kind.

I love my sister more than anything in this life,

I will choose her happiness over mine every time.

Reprising her rap about prioritizing Eliza ties together Angelica’s commitment to supporting Eliza. The added lines would work just as well in “Satisfied” because she puts Eliza’s happiness first then, too. It also recalls some of her intricate, difficult raps as a reminder of her intelligence. Angelica’s oratory reflects her characterization and themes throughout Hamilton.

Maria Reynolds is much less involved in Hamilton than Eliza or Angelica; she is in only one song. She makes a great impact, but her historical importance is limited to being a participant in the first United States sex scandal. However, Maria’s representation in the musical is very important. She is portrayed as a seductress, but the choice is clearly Alexander’s—the entire song about their affair centers on him trying to “Say No to This”—and he makes the wrong decision. While Maria is partially to blame, Hamilton represents her guilt as ambiguous, just as it was historically. Jasmine Cephas Jones, who plays Maria, explains that she decided “instead of playing it like a villain, I feel bad for her. There's always another side to the story.” She intentionally tempted Alexander as part of a con, but her husband is also abusive and she is desperate for help. Maria is simultaneously culpable of having an affair and blackmailing Alexander, and a victim of her circumstances and abusive husband. The musical’s depiction of Maria is well done because though it shows she shares the blame, she is not “slut-shamed” for her actions. The only person who calls her names is her own husband, who refers to her as his “whore wife.” Eliza has ample opportunity to openly despise Maria, as does Angelica, but both place the blame squarely on Alexander. Even Alexander himself, though he flies into a rage at realizing she set him up, desperately wonder “how could I do this?” Originally, the lyric did blame Maria (the “I” was a “you”) but Miranda and director Tommy Kail opted to change it because “Hamilton’s realization of his own culpability in this situation is far more compelling than blaming Maria” (Miranda 178). Alexander faces the consequences of his actions instead of passing them off on Maria, though her own guilt is apparent as well.

Maria’s rhetoric is limited; most of her few lines are fed to her by Alexander or her husband, James. Maria does not have a voice historically, as Alexander’s pen told her story and James manipulated her life. Thus, in her one song, she fills in the gaps after Alexander says “she said,” which he does five times in the first verse alone. He narrates her story, so her vocals are only what he remembers them to be; Maria has no voice of her own. During the second verse, Maria begins to cry that she is “helpless,” taking Eliza’s word of love and tarnishing it with her own desperation and manipulation, showing the depth of Alexander’s betrayal. Maria’s lack of voice in her song is as telling as the uniqueness of Eliza and Angelica’s rhetoric in their stories.

The role of women in Hamilton is important for representing women in the past while also having an impact on modern times. Hamilton sheds light on Eliza, Angelica, and Maria, three of the many women frequently ignored by history, and shows their significance. They are portrayed as strong women “making powerful choices at a time you would imagine there would be no power” for them. The musical celebrates some of the founding mothers and shows their impact because “they were not just sewing flags, they were actually the muse, like Angelica Schuyler was to Thomas Jefferson and to Hamilton.” Beyond educating modern Americans, the depiction of women speaks to current gender roles, establishing that women—in particular, women of color—are strong, intelligent, and have a place in society and politics. Chris Jackson, who plays George Washington, explains his favorite part of Hamilton is in the finale. He steps up behind Eliza to say she tells his story through her role in building the Washington Monument and revels in that moment, but her next line is to say she speaks out against slavery:

And in that moment, Washington realizes that he didn’t. And it is a moment

of shame for him. And I slowly bow and I back away from that; there’s a

strength and purity that she represents at the end of this story, and a

resilience, and that legacy moves forward in somewhat of a pure way

through Eliza.

Eliza has a place and a voice in her society, and uses it for good; good not even the first president was able to achieve. Angelica influenced some of the greatest minds in American history. Eliza sacrificed herself to ensure her husband would be remembered. Historically, Eliza all but erased her own story in her efforts to tell Alexander’s, exhibiting the selfless person “that women are so often asked to be, so often assumed to be, instead of [their] story being told.” Not only does this assumption contribute to the erasure of women’s stories, but it takes away the significance by making sacrifices like Eliza’s a given rather than a noble choice. Hamilton recognizes this flaw and gives Eliza control over her entire story, acknowledging her selflessness for the courageous choice it is. Her choice makes her the hero of the story; Alexander’s life is the center of the musical, but Eliza “makes it clear that without women, even some of history’s smartest, most powerful, most talented men would be resting in obscurity”; and by extension, the life-changing piece of art that is Hamilton would not exist either. Eliza is the true hero of the story, and Hamilton depicts her as such.

Angelica’s devotion to Eliza highlights the importance of female friendships and family. Her loyalty to Eliza is essential to her character, and the emphasis on women helping women is an important lesson even today. Maria, while depicted as a villain, is not shamed for her sexuality, and Alexander is forced to take responsibility for his choices, another moral still vital in modern times. Maria’s complex character reminds of the layers everyone has and exemplifies the importance of avoiding slut-shaming.

Ultimately, what makes these characters matter so much is that they exist at all. Eliza, Angelica, and Maria have been overlooked for centuries of history, but Hamilton brings them to the forefront. These women are not only a part of the story, but vital to Alexander’s life and well-developed as characters. The inclusion of women of color changes modern views on history, for the show highlights the former limiting situation of women, and how they were great despite that. The casting gives representation and ownership of this history to women and people of color in an unprecedented way. Hamilton gives women a voice in a time they were silenced, forcing everyone to reevaluate their views of the time period to include women and people of color. The inclusion of women creates a space for them and allows them to own their history, destroying generations of oppression and silence.

Hamilton’s depiction of women matters because these women matter, and this musical finally gives them an opportunity to shine. They helped to shape history, but are often erased in favor of their male contemporaries. By seeing both what they accomplished and who they were as people, we can learn lessons applicable to history class and present day living. Representation of women in any medium is essential, as there are still vast inequalities and oppression that women face every day. Hamilton gives women a voice and shows their strength, power, and significance so they will not be forgotten and to inspire women today.

Bibliography found here.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Development of Television

Television has changed immensely in its short existence. It is a young medium- younger even than film, because television sets did not make it into homes until decades after movie theatres were common. In recent years, television has developed into a more serious, relevant form of entertainment. The transformation of television is evidenced in the new ways shows are presented to viewers and the increasingly cinematic elements of television.

Television show seasons have been shortening in recent years. For many years it was traditional to have a twenty-two episode season, but that is no longer the norm. While some retain the old model, many shows today have only ten or twelve episodes per season. In the past, the goal was to generate the maximum number of episodes in order to make as much money as possible. The more episodes that aired, the more commercial spots the network can sell; in addition, in order to get syndicated (another way to make money off of the show), the usual goal was to have at least one hundred episodes. However, changes in formatting and technology have changed this set-up. There is now simply more shows, so it is unnecessary to have every show do a full season; for instance, Agent Carter fills the gap when Agents of SHIELD is off-air, and combined the two shows have about twenty two episodes.

(Source)

Streaming technology has advanced tremendously, and platforms like Netflix or Amazon Prime are not concerned with the number of episodes a show has in order to make it available, so there is less pressure to hit one hundred episodes. Moreover, there are storytelling benefits to shorter seasons. The cast and crew of a show is less likely to get burnt out with fewer episodes, and “actors, writers and producers seem to agree that storytelling can be more focused and deeper when presented over a shorter season” (Nodedog). In a twenty two episode season, it can be more difficult to make every episode directly relate to the plot arc, so there are often several filler episodes that do little to advance the plot. Shorter seasons offer a more concise, driven story. Some shows have changed the format even more drastically. For instance, each season of Sherlock consists of only three episodes, each of which are an hour and a half long. Other shows, like Luther, have six episodes, each an hour long. Formatting is just one of many changes the television industry is undergoing.

The way television is consumed is rapidly changing. In an NPR article, Linda Holmes recounts twenty five ways to watch a television show, which may not even be a complete list. Besides watching it live (which alone includes at least three different ways of watching), there is DVR, On Demand, reruns, DVDs, streaming from any number of providers, purchasing it digitally, and a multitude of resources (legal and illegal) on the internet. Theoretically, this makes it easier to access, but it also complicates the issue. It is unpredictable what will be available where, and when, because though consumers think of shows based on network of origin, it is rarely that simple. For example, Brooklyn Nine-Nine airs on Fox, but it is made by Universal Television, which is owned by NBCUniversal. This means there are many factors in who can decide where these shows are made available. Another result of the myriad of viewing options is that it is harder to get a handle on ratings. There is no longer one single statistic of viewers, and “to render a verdict the day after is lunacy” says CBS executive Kelly Kahl (Schneider). This makes it more difficult to distinguish between shows that are successful and those that are failing, but networks do not want a single number statistic. The ratings are important because they determine how much money they are making and since they do not make the same amount of money on each medium a single number is not helpful. How television is consumed will continue to change, but the object will always be to make money off of any and every medium.

There is another effect of these many different ways to watch television, and that is the sheer volume of material. Just a decade ago, in 2004, were forty-five original scripted shows on cable channels, but in 2014 there were one hundred ninety-nine. If you include the shows on network television and all of the new programming for the year (including talk shows, reality shows, etc.) the total is one thousand seven hundred fifteen. And then there are companies like Netflix and Amazon who not only host many shows to be watched, but produce their own original material.

(Source)

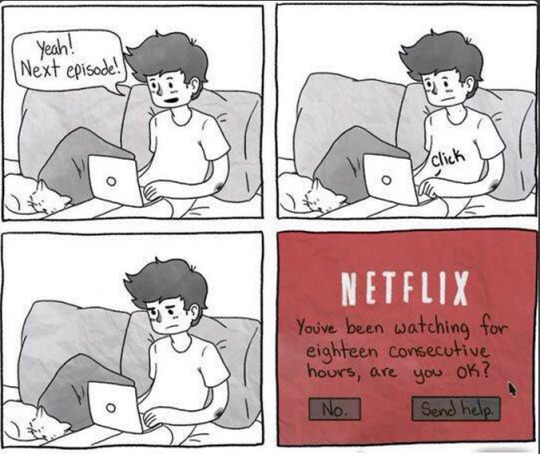

The amount of television available for consumption is massive. Consequently, ratings are dropping across the board, because viewers simply do not have the capability to watch everything. The market has become saturated. This has also resulted in the rise of binge culture. Netflix conducted a survey in which 61% of respondents said they binge watch regularly, and 73% said they have positive feelings towards binge watching. Netflix, along with other similar platforms, release all episodes of their shows at once, so viewers can watch them at their leisure, which often includes binge watching.

(Source)

Even on mainstream television, there are show marathons. TBS is airing all ten episodes its new show Angie Tribeca back-to-back, without commercials, for binge watching purposes. Technology and the huge volume of shows has lent itself to the rise of binge culture, and the entire way television is structured and viewed has changed drastically in recent years.

Television is also one of the most diverse mediums and deals with many current issues. In this area, it has actually outpaced film. It is monetarily risky to have a diverse cast in film. The business model that places a “Q score” on a person’s marketability devalues people of color; Emily Blunt revealed that the backers of the film Sicario offered to give more money if they changed the lead to a man instead of a woman; in the past thirty years, ten actors have won Oscars for LGBT roles (all of them straight). In television, however, there is an abundance of diversity. Orange is the New Black features a range of different ethnicities and sexualities, played by LGBT actors, and all but a handful of the main characters are women.

(Source)

Shonda Rhimes’ shows are famous for their diversity, as they use colorblind casting (roles are not written with an ethnicity in mind). Grey’s Anatomy has a great number of female characters, including a bisexual woman and a lesbian, and a large portion of the cast are people of color. The Fosters, Sense8, Brooklyn Nine-Nine all have LGBT characters of color; Empire, featuring a largely black cast, “broke a twenty-three year old record for an increase in viewership during the first five episodes” showing that a lack of diversity is not due to a lack of demand (Siegemund-Broka). Television not only contains diverse casts and characters, but tackles a myriad of current issues. This has been the case for years, but in the past these issues were addressed in an “after school special” way and one show often tried to deal with every current hot topic. Today, these issues are dealt with more by letting them play out in the story, and shows often focus on one area, but across the board, more issues are being dealt with than in the past. Grey’s dealt with abortion, PTSD, alcoholism, a homeless veteran, among many other topics over its eleven seasons. Orange is the New Black explores prison culture, America’s flawed penal system, the LGBT community (including transphobia), and rape. Breaking Bad depicts drug culture. There are many dystopian dramas, such as Under the Dome, that act as commentaries on the government and society. Wilson Cruz, a GLAAD representative, explains that "it's no coincidence that as Hollywood film has lost revenue and cultural relevance to television in recent years, TV has featured increasingly more diverse characters and groundbreaking stories” (Reynolds). Television shows are flexible and have a high turnover rate, making them much less risk adverse than the film industry. Thus, they are willing to be diverse and tackle these current issues, and therefore have surpassed film in this area.

There are many ways television has become comparable to film. Most obviously, some shows are tied directly into movies. There have been several shows set in the Star Wars universe, and presently there are four Marvel shows that are a part of the current Marvel Cinematic Universe with more to come. The plots and characters of the shows are involved and affected by the events of the movies, making the universe even larger (over seventy hours of this universe exist) and nuanced. Agents of SHIELD, one of the current Marvel shows, has filmed on location in many countries including Spain, Sweden, France, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Usually, television shows stick to local locations and in-studio shooting, but that is beginning to change. A notable example is Sense8, which was “filmed around the world in nine locations — San Francisco, Chicago, London, Reykjavik, Seoul, Mumbai, Berlin, Nairobi and Mexico City” (Morabito). The show takes place around the world, and all of it was filmed where it was set. Galavant just finished filming on location in Morocco. Budget was always one of the main constraints on this type of filming, but more and more money is being spent on television shows. ER clocks in as the most expensive show ever made, when for two seasons NBC paid a total of $440 million. However, most of that went to actors pay. A better example is the currently airing Game of Thrones. The HBO show gets $60 million per season, averaging $10 million per episode; for comparison, the average cable show gets $2 million per episode. This is due largely to the location shooting (the most recent season was filmed partially in Spain, and earlier seasons visited Croatia, Morocco, and Malta), but also to the special effects, another increasingly cinematic element of television.

Special effects are on the rise in television shows, sometimes even on the scope of film effects. Game of Thrones has featured dragons since the end of season one, and they have doubled in size every year. In the fifth season, they are forty feet long and breathe real fire. The approach to the effects “was to animate the dragons in advance and take that animation and apply it to a motion control camera rig” (How VFX Wizards Brought the Game of Thrones Dragons to Life).

youtube

They then attached a flamethrower that shot fire up to fifty feet and filmed live fire being shot at stuntmen. The results are dragons comparable to those in any film, including Smaug in the big budget film The Hobbit.

(Source)

Torchwood, a spinoff of Doctor Who, features some great special effects as they grapple with all kinds of aliens. In one episode, they battle creatures called Weevils.

(Source)

They have prosthetic masks, with each hair individually placed. Some of the movement is operated by the wearer, but much of it is operated remotely by radio controlled animatronics in the lips and brows. Breaking Bad has an abundance of superior special effects, primarily bloody ones. Showrunner Vince Gilligan did not want to glorify violence, so injuries had to be messy and realistic. That meant lots of blood, squibs, sprays, and other devices to achieve that realism. The final scene of the series featured a machine gun and used over two hundred fifty squibs. Special effects have become just as important to television as they are in film.

Television has also made tremendous advancements in cinematography. Traditionally, shows were shot on a stage using one or two cameras with little movement. Artistry was not the primary concern. Today, however, that is changing. Once again, Breaking Bad is a prime example. The use of color and the unique shots and angles rival film in their complexity, innovation, and effectiveness. Color plays a huge role in the appearance of Breaking Bad, particularly with the vast, southwestern landscapes. Mexico is a repeated, important location in the show, and director of photography Michael Slovis used a filter to give the country its own unique color and saturation to easily distinguish it from Albuquerque and set a tone for the location. The lab was lit with bright, harsh lights so there was high contrast, adding a clinical, sterile look to it and giving the space a distinctive appearance and feeling. This show is famous for its unique POV shots. A repeated shot is a perspective from below which is now iconic Breaking Bad, shooting from the view of anything from a wine glass to a toilet.

The show is also famous for different types of moving POV shots, like the “shovel cam” or “Roomba cam” that moves around from the perspective of an inanimate object.

Hannibal also exhibits fantastic cinematography. The show is thematically dark, and this plays out literally as the cinematographer James Hawkinson chose to consistently use very low lighting. For instance, in the very first episode, Hawkinson explains how in the first shot of Hannibal, “I lit him like just a death head, chewing in the darkness” (Fienberg).

(gif credit to tumblr user @hannibalsgifs x)

The effect is stunningly ominous; the first shot of this man is a symbol of death. The show is also very conscious to make everything artistic, from the gourmet food to the horrific, gory murders.

(Sources: x x)

The characters deal almost exclusively with serial killers, and their violence is their art, which the show portrays with a horrific, disturbing beauty. Sherlock has taken many new approaches to cinematography that are highly effective. One of the most notable is the use of text on the screen which works to avoid awkward shots of phones displaying text messages and even more impressively, show the thought process of Sherlock himself.

(gifs via tumblr user @everythingifs x)

In the season two premiere, there is an incredible slow-motion sequence shot using a Phantom Camera. It allows for the fast, complex action to be seen and understood and it is tremendously effective and awe-inspiring.

There are also a myriad of creative transitions in the show, particularly from reality to memory or imagination. These transitions portray the fine line between reality and what is in the mind in a creative way, like when Sherlock goes from standing in a field to lying in bed in one smooth shot.

Cinematography in television is becoming increasingly more comparable to that of film and has advanced tremendously.

Long-form storytelling is also becoming more popular in television. In a sense, many of these shows feel like one story- one very long movie. Some take this to an extreme, like True Detective which had a single writer and director for the entire season, making it one story and artistic vision, like a movie. Adam Chitwood explains that “It’s generally acknowledged that the difference between film and TV is that film is a director’s medium and TV is a writer’s medium” (Chitwood). Long-form storytelling requires a greater unity of these two so that the entire show feels like one story instead of being fragmented by episodes. Instead of being episodes of a show, they are merely installments in a singular, greater story. Breaking Bad is once again a superb example, because from the first episode to the last, there is one story and main conflict that drives the plot. Not only that, but the consistency of colors, cinematography, styles, and other visual elements unify the show into one, very long movie.

youtube

Broadchurch is not long-form to that extent, but rather than solving a murder every forty minutes, this show lets the clues come out over the course of a season, so the mystery is nuanced and the characters have depth. Long-form storytelling by no means works for every show, but it is becoming more popular as it allows television to tell more complex stories.

Television has come a long way in its short history. This change has only accelerated in recent years as it became a more serious and important form of entertainment. Advances in technology have changed both the way shows are formatted and how audiences consume them. Television tackles current issues and is able to travel and use special effects to tell a larger story. It has also become more cinematic and some shows use the format to tell a deeper, more complex story. Television is ever-changing and has developed into a medium different and yet equally as important as film.

Bibliography

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bibliography

For project in this post.

Breaking Bad - The Evolution of Walter White. Perf. Bryan Cranston.Youtube. JakeWarner96x, 17 Oct. 2013. Web. 2 Dec. 2015.

"The Changing TV Landscape: Original Scripted Programming Continues to Expand, but at Some Point the Bubble Must Burst." Cancelled Sci Fi. Axiom's Edge, 01 July 2015. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

Chitwood, Adam. "Why Filmmakers Are Flocking to Long-Form Storytelling." Collider. Complex Media, Inc., 06 Oct. 2014. Web. 29 Nov. 2015.

Fienberg, Daniel. "'Hannibal' Cinematographer James Hawkinson on the Show's Disturbing, Dark Beauty." HitFix. Hitfix, Inc, 25 June 2015. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

"Filming Locations." Game of Thrones Wiki. Wikia, n.d. Web. 27 Nov. 2015.

Holmes, Linda. "Television 2015: With 25 Ways To Watch TV, Does The House Always Win?" Monkey See. NPR, 18 Aug. 2015. Web. 29 Nov. 2015.

"How VFX Wizards Brought the Game of Thrones Dragons to Life." Creative Bloq. Future Publishing Limited, 29 June 2015. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

Kelley, Seth. "10 of the Most Expensive TV Shows Ever Made." Marketplace. American Public Media, 2014. Web. 29 Nov. 2015.

Making of Episode 516 Felina: Breaking Bad. AMC. AMC, n.d. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

"Marvel's Agents of SHIELD Filming Locations: Season One." Agents of SHIELD Filming Locations. Seeing Stars, n.d. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

McLean, Thomas. "EMMYS: Cinematography." Deadline. Penske Business Media, 23 June 2013. Web. 28 Dec. 2015.

Miller, Liz Shannon. "Has TV Made the Marvel Cinematic Universe Into A Nerd's Dream Come True or an Addiction?" Indiewire. Indiewire, 8 May 2015. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

Morabito, Andrea. "Looks Could Kill on New Netflix Series 'Sense8'." New York Post. New York Post, 4 June 2015. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

Nededog, Jethro. "5 Reasons Why TV Networks Are Ordering Shorter Seasons." Business Insider. Business Insider, Inc, 18 June 2015. Web. 27 Nov. 2015.

"Netflix Declares Binge Watching Is the New Normal." PR Newswire. UMB, 13 Dec. 2013. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

Phillips, Kashida. "The Most Diverse Shows on TV Now." VH1. Viacom, 25 July 2015. Web. 02 Dec. 2015.

Reynolds, Daniel. "Why Television Is Outpacing Film in Diversity." Advocate.com. Advocate, 17 Nov. 2015. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

Schneider, Michael. "Hot Topics: Can TV Still Tackle Real Issues?" TVGuide.com. TV Guide, 09 Dec. 2014. Web. 29 Nov. 2015.

Schneider, Michael. "The Measure of Success." TV Guide 12 Oct. 2015: 10. Print.

Season 4 Making of Game of Thrones. Youtube. Pixomondo, 29 Jan. 2015. Web. 02 Dec. 2015.

Sherlockology. "A Look at How BBC Sherlock Visuals Are Created." Metro. Metro, 22 Nov. 2013. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

Siegemund-Broka, Austin. "Diverse Casts Deliver Higher Ratings, Bigger Box Office: Study (Exclusive)." The Hollywood Reporter. The Hollywood Reporter, 25 Feb. 2015. Web. 29 Nov. 2015.

"TBS to Launch Rashida Jones Comedy 'Angie Tribeca' with 10-episode Mega- marathon in January." US News. U.S.News & World Report, 5 Nov. 2015. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

Thomson, David. Breaking Bad: The Official Book. New York: Sterling, 2015. Print.

Torchwood Neill Gorton Interview. Perf. Neill Gorton. Youtube. BBC, 06 Oct. 2006. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

All gifs not credited were made by me.

0 notes

Text

Mad Max Fury Road Review

Mad Max Fury Road is an excellent film that I thoroughly enjoyed. It is very visually pleasing, the story is interesting, and the characters are even better.

Most dystopian films, including the old Mad Max movies, do not use much color. They’re typically very sterile and/or washed out, but Fury Road does the opposite. The desert is full of bright oranges and yellows and the sky is a vibrant blue. There is a long night sequence, but instead of being black, it is lit with a dark but bright blue. This makes the movie visually stunning and I really enjoyed this use of color.

The plot was interesting and fast-moving. The action sequences were extremely well done; instead of being a deluge of quickly cut, fast moving shots that are impossible to follow, it was edited to be intense and rapid yet able to followed.

The movie can very easily be interpreted as a feminist film; though Max owns the title of the film, he is surrounded by almost exclusively women. The diversity among them is incredible; not just ethnically, but each has a unique personality and take on the world, and each is interpreted as valid. Some are angry and glad to be away from their abuser/rapist/slave owner. One is afraid of freedom, something they have never had, and wants to go back. One is able to instinctively trust Nux, even though she has every reason not reason to- he is a man, and furthermore, loyal to her abuser-but she does, and her instincts are right. Each woman grows and develops throughout the movie, using their perceived weaknesses against Immortan Joe.

It’s also interesting to me how they deal with motherhood. The Many Mothers are clearly a matriarchal society, while Immortan Joe’s dictatorship is very patriarchal. Immortan Joe values children as commodities, and woman as the things that provide children; childbirth is important to him, but motherhood is not. The Many Mothers, on the other hand, are the opposite. Furiosa, who is infertile, is not treated as lesser because she is just as capable of helping and raising children as anyone, regardless of her ability to give birth. She helps to care for and “raise” these women she rescued just like a mother, a value clearly taught to her as a part of the Many Mothers. In a society that is obsessed with a woman’s ability to reproduce, I think this is a very important message.

The themes, characters, and cinematography of this movie were excellent. I highly recommend it as a fantastic action movie and great representation of women in an industry where both are too rare.

1 note

·

View note