Video

Animation for a Digital Revolution graphics project,

2016

2 notes

·

View notes

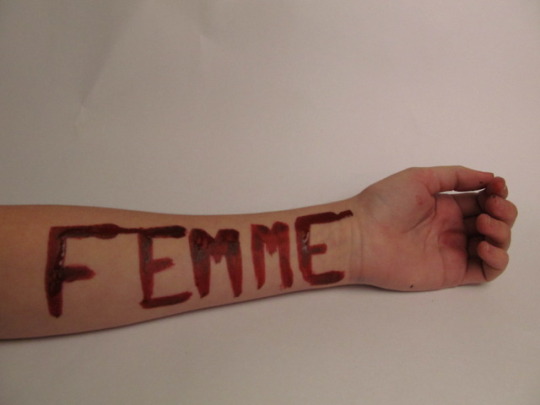

Photo

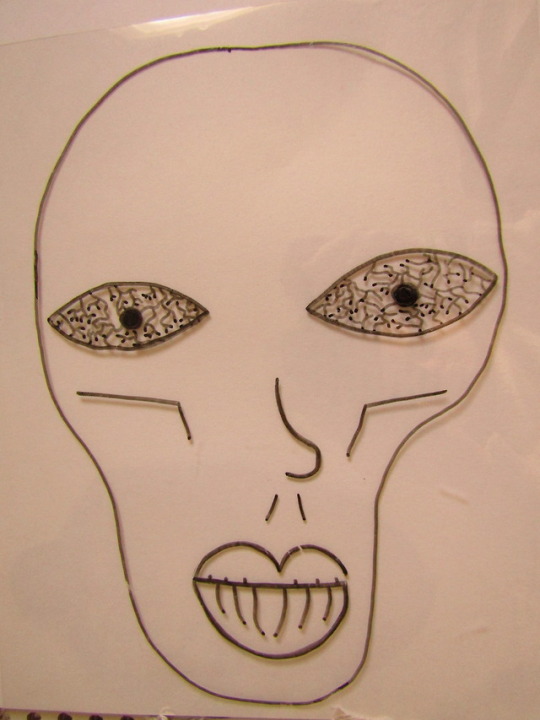

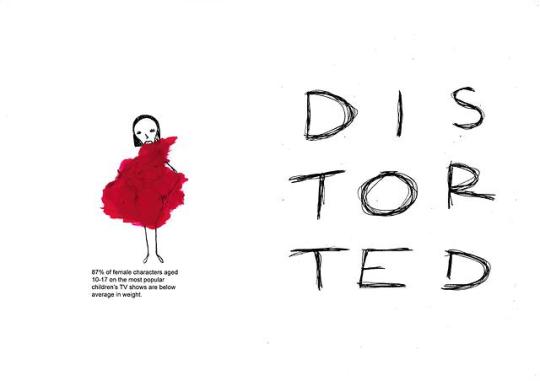

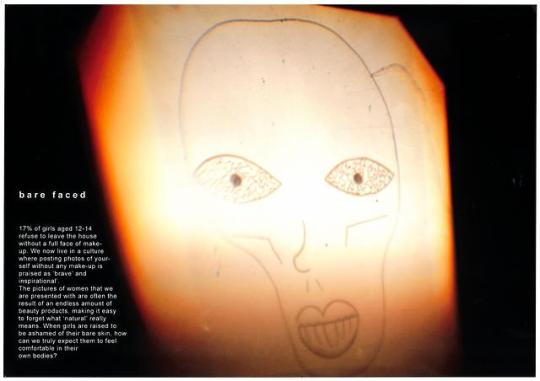

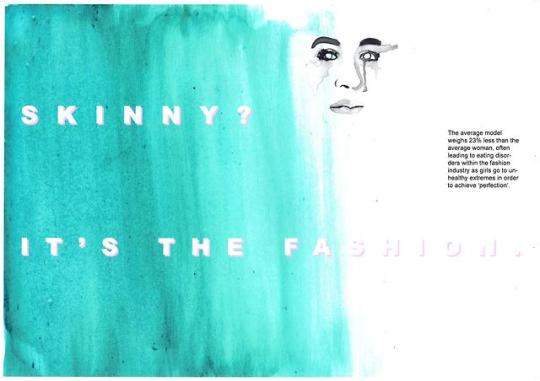

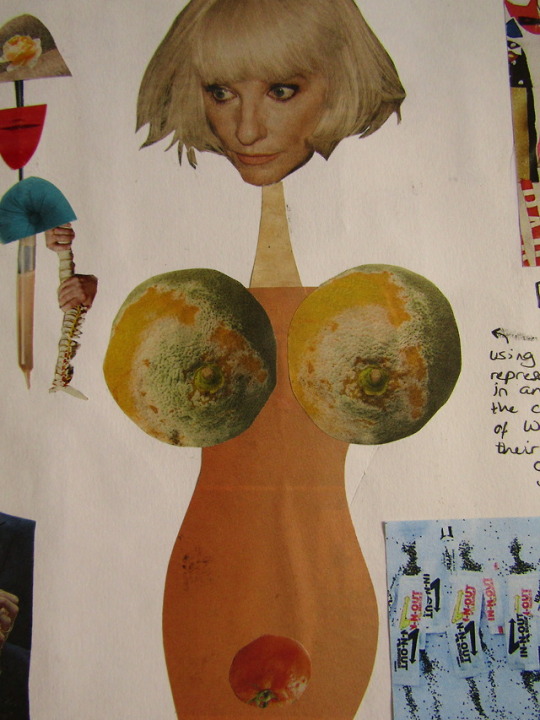

Final piece for graphics project exploring female representation.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

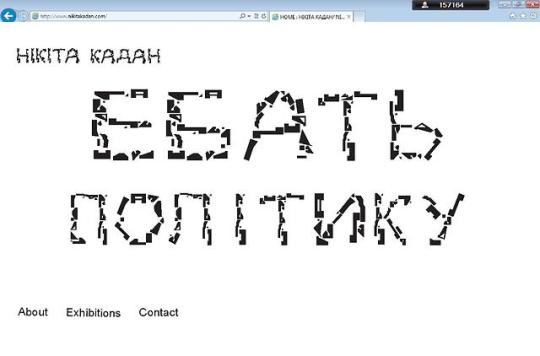

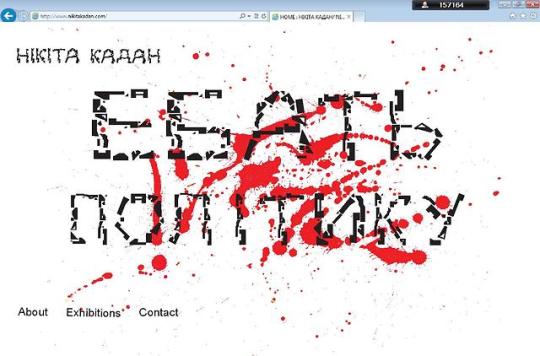

Website landing page for Nikita Kadan inspired typeface

1 note

·

View note

Photo

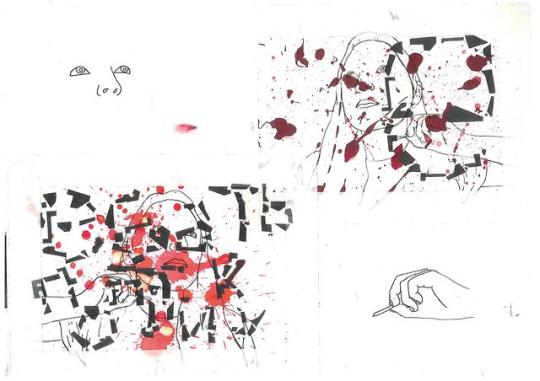

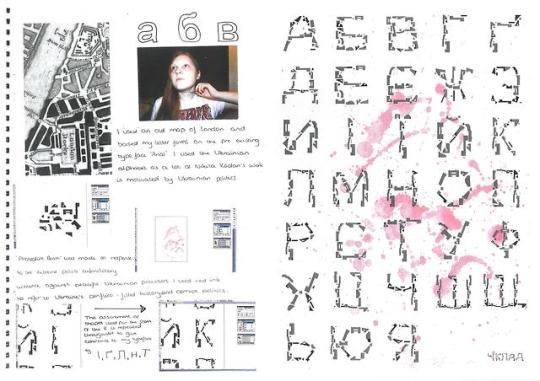

Typeface development, inspired by Nikita Kadan.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

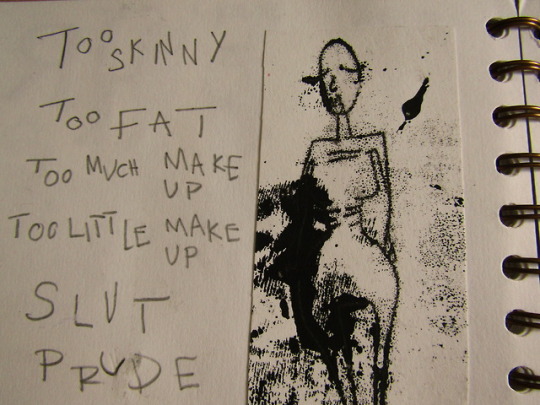

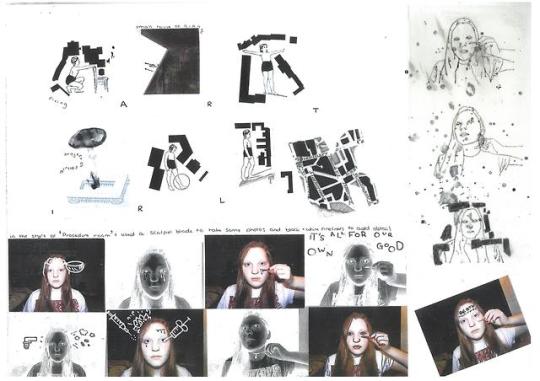

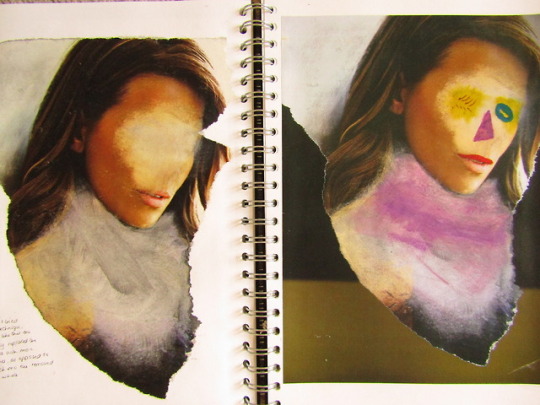

Collage and cellulose thinner experiments for a graphics project on female representation

1 note

·

View note

Text

Critical Analysis of ‘Vertigo’

Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) was described by critic Robin Wood as ‘a perfect organism’. This description is oddly apt as with each watch my personal understanding of the film and subsequent response to it has changed, as though the film itself is alive, an ‘organism’ as inconsistent as its plot and its characters. Through an intense analysis of the film and the reading of multiple others’ interpretations, new meaning is constantly being given to all parts of the film, and every time I watch it, I do so in a new light, with a slightly altered perception from my previous viewing.

The character of ‘Madeleine’, who is in fact Judy Barton, is intentionally created as an enigma, designed to allure both the spectator and Scottie as the uncertainty surrounding her apparent supernatural possession draws us in, intrigues us, and causes us to seek out the intellectual pleasure (one of the genre pleasures defined by Altman) that would come with uncovering the truth. However, the grey suit worn by Judy as she plays the part of Madeleine is rather understated, plain and bland, to the point where Kim Novak initially refused to wear it as it did not seem fitting for a leading lady. As a result my initial perception of this ‘Madeleine’ was not as taken with her as Scottie appears to be, as although she personifies the typical ‘Hitchcock Blonde’, her make-up and costume are not overly glamorous and she does not speak until 44 minutes into the film, meaning she appears overtly passive and with a personality that leaves much to be desired. But after seeing the film as a whole multiple times and reading the interpretations of various critics, I now appreciate why it is so important that ‘Madeleine’ appears this way. The grey suit is coloured in a way that evokes a sense of the mythic; it is pale and almost ghostly, which could be seen to link to the fact that Madeleine is apparently possessed by the late Carlotta Valdes, as well as being a cataphoric reference to the apparent suicide of ‘Madeleine’. But this could also be explained by Zizek’s point that Scottie ‘mortifies’ Judy in that he essentially kills her in order to realise his fantasy and bring ‘Madeleine’ back to life. In light of this reading, the ghostly appearance of ‘Madeleine’ in the grey suit could be foreshadowing the metaphorical death of Judy as she allows herself to be stripped down and built back up to the image of Madeleine that Scottie holds in his mind’s eye.

A scene that has developed a new meaning with each new watch is the moment the spectator and Scottie are introduced to who we are lead to believe is Madeleine Elster in Ernie’s restaurant. ‘Madeleine’ appears in a black dress with an exposed back, and a green shawl. She appears elegant and the camera pushes in on her centre frame whilst the music swells. The moment is typically romanticised and arguably leads the spectator to suspect that a romantic connection will form between Scottie and ‘Madeleine’. One interpretation of Vertigo is that it is an analogy of the relationship between the spectator (Scottie) and a text (‘Madeleine’) and so the shots occasionally appear to be point of view (POV) but as proved by the push in are actually described by Joyce Huntjens as ‘subjective shots’ meaning the gaze of the viewer coincides with the gaze of Scottie, without the continuous use of actual POV shots. In doing this the spectator is encouraged to see ‘Madeleine’ as Scottie sees her – a sophisticated and captivating young lady who appears as an intriguing embodiment of the ideal woman – and as it is later revealed, as she was constructed to be seen by both Elster and Judy. This parallels with the spectator’s experience as they are encouraged to view a film or indeed any text as intriguing, or else why would they want to watch it, and the film is of course constructed by an entire crew of people who all have their own influence on how the final product is seen, from the director to the set dresser.

When ‘Madeleine’ walks forward to the centre of frame, creating a profile, the music swells, the intense red colouration provided by the walls of Ernie’s lightens, and there is a soft focus on the mid-ground and background of the shot. The shot is therefore romanticised and ‘Madeleine’ appears to become the passive recipient of the ‘look’ and the male gaze, as defined by Laura Mulvey as the way in which women are seen as objects for male gratification, encouraging the idea of ‘Madeleine’ as the ideal woman. Richard Allen equated the allure of ‘Madeleine’ to the allure of the surreal, aestheticised world of the film, particularly evident in the scene at Ernie’s where the shots and lighting changes imply a deviation from reality. Just as this sequence in Ernie’s is constructed, and makes this construction clear to the spectator by partially abandoning realism, the spectator and Scottie later learns that the ‘Madeleine’ we thought we knew was also a construction of Elster’s design enacted by Judy. The profile shot can also be interpreted upon later watching, in light of this revelation, to emphasise how every act of Judy is at this point designed especially for Scottie, to intrigue him and make him fall in love with ‘Madeleine’. It also hints that there is a side to ‘Madeleine’ that Scottie is not aware of, as she presents a ‘Janus face’, described by Allen, which suggests a dark side concealed beneath an outline of perfection. This dark side is Judy, whose reasoning behind helping Elster are never fully explored, but regardless of the justification she willingly participates in the deception and manipulation of Scottie, taking advantage of his illness and desire to feel masculine. Whilst brief details suggest a past in which she was abused by older men which could explain why she went along with Elster’s plot and later fell in love with Scottie, her actions were ultimately immoral and so she is clearly the ‘dark side’ that the profile shot of ‘Madeleine’ relates to. Conversely, ‘Madeleine’ represents the perfection which disguises this other side as she is not real, merely a fabrication, and so can be presented without any of the flaws that would occur if she were a real woman.

Vertigo is a film which is inherently polysemic and a new meaning becomes clearer to me with every reading, particularly with the presentation of Madeleine, played by Judy, played by Kim Novak. Critical readings have given me more of an insight into how else certain elements of the film could be interpreted, and a greater understanding of the contexts in which the film were made (such as learning that Kim Novak felt that Hitchcock was obsessed with the look of her, ensuring everything was exact, as Scottie does when he remakes Judy to fit his image of Madeleine) have enhanced my perception of the film, developing my interpretations and ideas of the film itself and the topics it presents.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

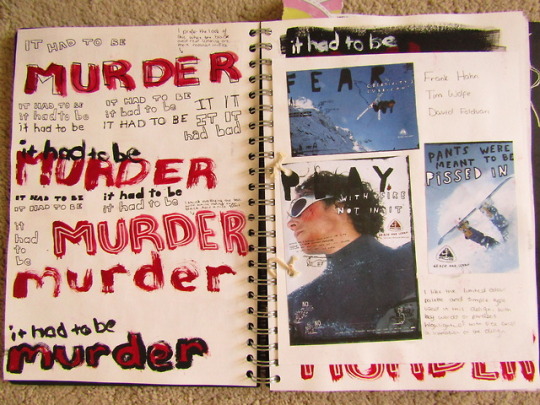

Typography work for a graphics project on It Had To Be Murder by Cornell Woolrich.

2017

1 note

·

View note

Text

FAITH (Shooting Script)

Wide shot of REBECCA looking in to camera. She is stood against a plain, white wall, and only the top half of her body is visible.

Rebecca My name is Rebecca Isaacs. I am seventeen years old.

Cut to a shot with REBECCA in the same position but a hand is covering her mouth. This shot lasts for less than a second.

Cut back to the original shot

Rebecca And I can see the devil.

A hand slowly moves over REBECCA’S mouth.

Cut to black

‘FAITH’ appears in the centre of the screen (white Arial Bold)

Wide shot shows YOUNG REBECCA cowering in a corner, knees drawn up to her chest, looking at something above the camera.

Rebecca When I was a child I saw the goodness and light in everything

Someone, out of focus and wearing black, steps in front of the camera so the view is obscured.

Rebecca But then I saw him

Cut to a wide shot of DEVIL, who is wearing a hood covering their face. DEVIL moves their head as the following line is heard. This footage could be sped up.

Rebecca Mother says the devil came to punish me for my sins. He hasn’t left my side since, though I have lived a life free of corruption.

Omniscient shot shows REBECCA stood in front of DEVIL who has their hands over her eyes.

Cut to a shot of REBECCA staring into a camera, mirroring the opening shot. DEVIL is stood behind her left shoulder and slowly puts their right hand on REBECCA’S left shoulder.

Rebecca Even when I cannot see him, I can feel him. He makes my heart heavy and my mind numb. I either feel inexplicable sadness or nothing at all, and it exhausts me.

Cut to wide shot. REBECCA and DEVIL are in the same position but there are lots of people surrounding them.

Rebecca At times when I am surrounded by people and should feel joy I am isolated, completely alone in the crowd.

Close up of REBECCA’S face staring into the camera. When she says ‘I pray’ the camera should cut to a zoomed out version of the previous shot in which REBECCA is kneeling in prayer with her eyes closed.

Rebecca I have been told to but my faith in God and so I pray every day for release from this nightmare I’m living

(opens eyes, looks straight into camera)

But the devil is persistent.

Cut to a wide shot of DEVIL, again moving their head which is lowered to hide their face.

Rebecca Is this a test? Is this a punishment?

DEVIL raises their head, but their face is still partially obscured by the hood, and takes a step towards the camera.

Rebecca Is this all my life is going to be?

Cut to a wide shot of REBECCA, as in the beginning, but with her head lowered like DEVIL. As the following lines are heard she raises her head, there are tears on her face, and she looks directly into the camera. REBECCA slowly raises a gun to her head.

Rebecca I want to be able to trust my faith but my prayers have gone unanswered for too long. I can only see one way to free myself.

REBECCA closes her eyes and a hand joins hers in holding the gun.

Cut to black.

Credits

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reflective Analysis of ‘The Dreamer’

Our aim was to create a short psychological horror film detailing a girl’s battle with her violent fantasies, subtly building tension to create an unsettling atmosphere and polysemic narrative. The target audience was 18-35 year olds; as our film was more niche our audience was more likely to be those who frequent film festivals and galleries where the film might be shown, as well as genre enthusiasts. Due to the female lead not being positioned as someone to be rescued, the film was intended to appeal more to women who reject the archetypal ‘final girl’, defined by Clover, as a paragon of innocence. Our main influences were the work of Richard Kelly and Jan Švankmajer; Kelly’s Donnie Darko features Frank, a physical manifestation of the eponymous Donnie’s subconscious; we used this idea in The Dreamer and included a masked figure in multiple shots. Švankmajer’s work also heavily informed our choices with editing and sound as we used exaggerated noises and quick jump cuts to express the mania and disconnection from reality felt by our protagonist; we drew particular inspiration from his films Alice and Little Otik . My main responsibilities in our film were mise-en-scene and editing.

The film features a lack of significant objects within the frame. By avoiding clutter I hoped to direct the eye more and put the sole focus on the protagonist or blood spatter, enhancing the reading of the black and white sections particularly as being set within the protagonist’s mind. She was alone with her thoughts and felt completely isolated, the only company she finds is the masked figure whose identity adds tension and develops fear due to a sense of the unknown and creation of an enigma code in relation to Barthes’ narrative codes. The blank mask also allows the protagonist to project her fantasies, hence why the mask is shown with blood spatter around the eye as an outward expression of the protagonist’s desires to cause harm to others.

Including multiple jump cuts into the film was intended to create a sense of general lack of control and chaos. The first set of jump cuts occurs when the protagonist is sat at the desk and I cut to the masked figure in various places around the room, whilst the protagonist remained central and stared into the camera. This sequence allowed for polysemic readings as it could be interpreted that by creating an extra-diegetic gaze, the protagonist is pleading for help. She is powerless to stop the masked figure’s advance and the jump cuts show her panicked state as she can offer no resistance, only silently beg the spectator to some to her aid. This reading is more in fitting with the typical female character in mainstream horror - the victim in need of saving who is usually saved because of her innocence and femininity. However an alternative interpretation would be that the protagonist does not want to stop the masked figure. By continuing to stare blankly into the camera she creates an uneasy atmosphere as the spectator is forced to watch the events unfold with no resistance from the protagonist. This suggests that the protagonist does not need rescuing as stereotypes would suggest, but should perhaps be feared rather than pitied, challenging the idea of women as passive objects raised in Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze.

Our final project was less subtle in its build of atmosphere and sense of horror than anticipated. Looking further into Švankmajer’s work encouraged us to create a more visceral piece with fake blood and the inclusion of a prosthetic stab wound. However, I think that we still were able to create an effective film that portrayed a fractured and violent mind. This project allowed me to learn a lot of new editing skills; as the film was more experimental and a tale of the subconscious, there was less pressure to create a sense of realism, allowing me to experiment with a variety of techniques whilst editing such as adjusting the colour and overlaying multiple shots.

When screening with a test audience I found their comments useful in allowing me to see more polysemic readings of the text. One particular choice that was brought up was the decision to drop parts of the film into black and white. When filming the interview style sections we struggled with lighting as the lights on location were much warmer than anticipated. This would have meant those scenes would not match the nature of our film as we were trying to create a sinister, unemotional character so lighting her with warm tones would not have worked and may have ruined the overall cinematic quality of the piece. By dropping those shots into black and white I was also able to emphasise the dullness of the protagonist’s mind; she only sees in colour when imagining scenes of blood and excessive harm. The aesthetic juxtaposition of the black and white with colour footage further enhanced the sense of surrealism and conflict in the protagonist’s mind. Our test audience was primarily teenagers and their positive responses and realisation of our aims was encouraging and conveyed that we had created a piece suitable for our target audience.

Whilst we did receive some comments with areas for development, the points picked out to improve upon were also highlighted as areas others liked well. This showed how open our film was to a variety of readings from individual spectators, something which we hoped to convey with our film; it lacks realism and so can be informed by the spectators pre-existing views and experiences, an idea presented by Hall who argued that audiences encode and decode texts differently depending on the individual. This empowers the audience and allows for them to apply their own meanings to texts that may not have been originally considered or intended. Overall I think we were able to create a successful piece that fulfilled our aims and had a clear narrative, despite the deeply chaotic mind of the protagonist.

1 note

·

View note

Video

Animation for a Digital Revolution graphics project,

2016

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Imagery for a Digital Revolution graphics project,

2016

1 note

·

View note

Text

How far German Expressionism was developed by directors and how far by other influences

2017

Norbert Lynton said that “all human action is expressive… all art is expressive of its author and of the situation in which he works”. Therefore, the link between directors and their surroundings is undeniable; whilst a film may technically speaking be the creation of it director, it is also a creation of the many other outside influences which would have affected a director and his choices when making the film. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (Weiner, 1920) and Nosferatu (Murnau, 1922) were both products of the German Expressionist era which lasted from 1920 until 1927 and was a result of an isolated Weimar Germany, whose people were left shaken and horrified by the aftermath of WWI. A cinema import ban meant that the demand for films was not met by imports from only Denmark and Sweden and so UFA, as a result of inflation driven cinema as well as public demand, produced 500-600 films annually. This made it the largest European film production studio until WWII, with its films clearly showing the effects that post-WWI Germany was having on its people.

Widely regarded as the first true German Expressionism film, Weiner’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari was hugely instrumental in establishing key aesthetics and themes of the style, namely the use of highly stylised visuals. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari shows this through its use of painted shadows and chiaroscuro. The painted shadows add to the sense of abstract expressionism created by the set, which was designed by Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann, and Walter Röhrig, creating a world which was not realist but rather representational. The horrors of Weimar Germany would have been all too common to the viewers at the time, indeed in his essay Where The Horror Came From David Hudson noted that 700000 Germans starved to death between Armistice Day and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and thus for Germany horror was both a reality and a fascination. As classified by Young and Rubican, certain audience members could have been ‘strugglers’, meaning that they watched films as a means of escape from their everyday life, whereas some may have been ‘reformers’, indicating that they are intellectual and socially aware; by adopting the expressionist style The Cabinet of Dr Caligari and films like it would have offered a take on the events of the day that were not realist, and therefore allowed some form of escapism, but also addressed the issues of the day that were highly relevant to audiences upon the film’s release.

An example of this in The Cabinet of Dr Caligari could be that one interpretation of the films painted shadows could be that they represent control. Shadows are supposed to be natural, fluid results of an object blocking light. When shadows are cast by living objects in the way of the sun it is within their nature to move and so by having them painted and static the common German Expressionist themes of a distrust of authority and extreme paranoia were reflected as it could indicate an unnatural control by a larger power. However, a more literal reason for the painted shadows was that due to the economic crisis that Germany found itself in after the war, electric lighting could not be relied on and so by physically painting the shadows onto the set the need for extra lighting was lost. Either way, whether the shadows are interpreted as a symbolic representation of the unimaginable, fear-driven reality of Weimar Germany, or just as a response to the need to reduce costs brought in by electric lighting, their existence within the film is clearly a result of outside influences and the director and set designers’ responses to that.

Most German Expressionist sets were studio made, however Murnau created the exception to this in his film Nosferatu which was filmed on location and so lacked the constructed and controlled mise-en-scene which characterised The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, but still employed chiaroscuro and induced an oneiric effect. Hans Helmut Prinzler’s The Restless Republic notes Murnau’s ‘personal and emotional interest in art’ claiming that Nosferatu ‘would be unimaginable without the scenes taken from paintings with which Murnau was so familiar’. It is clearly Prinzler’s opinion, therefore, that there was an inextricable link between the world of fine art and the world of cinema in Weimar Germany. Expressionism itself existed in art before it was adopted as a style by film and Murnau began his career by studying art history and Lotte Eisner found that when it came to taking inspiration from famous paintings ‘Murnau elaborated the memory’ meaning that whilst the influence of fine art may not be clear in exact replicas, it is clearly there in a more expressive sense. This is clear in moments during the third act of Nosferatu where Murnau makes use of the depth of field and chiaroscuro to create suitably German Expressionist imagery, and when Count Orlock’s face is seen in a close-up, framed by jagged shards of wood creating harsh lines within the frame. These instances link to the composition of Expressionist art – an element that Prinzler noted was one of the key components brought into Expressionist film by the outside influence of fine art of the era.

The German Expressionism movement was born of a time with extremely high rates of violence, rape, murder, and a loss of innocence. After the first World War, Germany found itself cut off from the rest of the world and struggling to deal with the loss of loved ones and economic crisis it found itself in; German Expressionism was a way of reflecting a broken nation, horrified by the unimaginable reality of the everyday. These contextual issues influenced the films of the era and the directorial choices made by filmmakers who used harsh lighting, bold visuals, and grotesque images to make the world appear as it felt. The attack of Cesare on Alan in The Cabinet of Dr Caligari has been seen as being allegorical of a rape scene, with the dagger acting as a phallic symbol, and Nosferatu’s Ellen is depicted as a feminine ideal, first seen playing with a kitten, framed by flowers, and she later becomes pursued by Orlock. Both these examples, as well as the mise-en-scene of both films, indicate how the threats of the everyday had an undeniable influence on the work of filmmakers at the time and the director’s decisions were not only their own, but also indicative of the people they were made for, and the society that they were made in.

1 note

·

View note

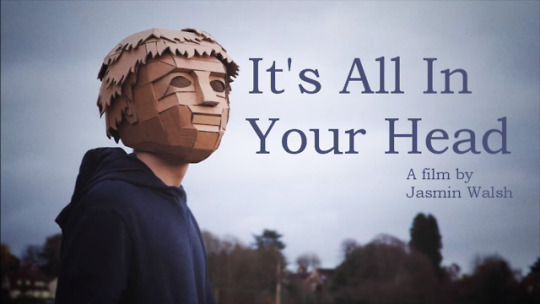

Video

vimeo

It’s All In Your Head. 2018

Random Acts, Channel 4

1 note

·

View note

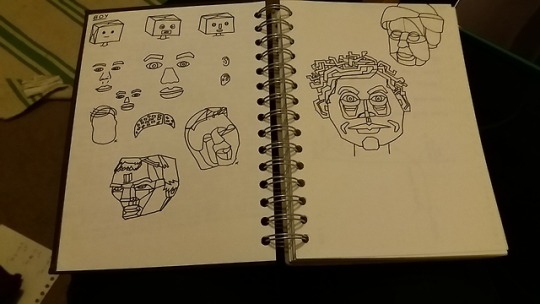

Photo

Mask design for It’s All In Your Head, 2018

Mask created by Amanda Haas

1 note

·

View note

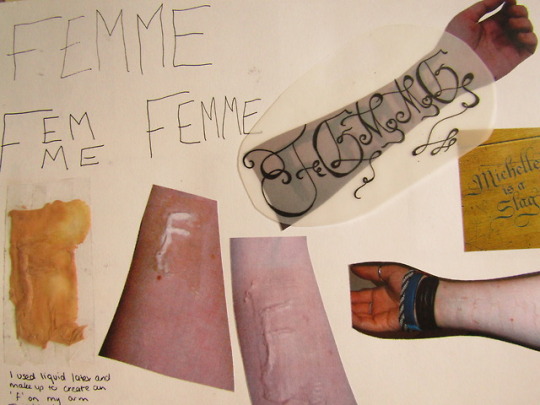

Photo

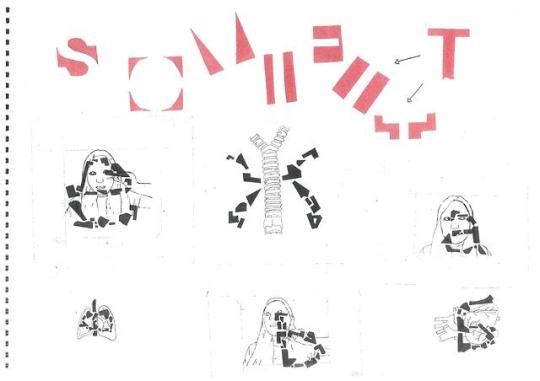

Lettering experimentation for a project on female representation.

2017

1 note

·

View note